Smoking cessation

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2010) |

Template:Globalize/USA Smoking cessation (colloquially quitting) is the process of discontinuing the practice of inhaling a smoked substance.[1] Smoking cessation programs mainly target tobacco smoking, but may also encompass other substances that can be difficult to stop using due to the development of strong physical addictions or psychological dependencies resulting from their habitual use. This article focuses exclusively on cessation of cigarette smoking. However, the methods described may apply to cessation of smoking other substances.

It is believed that very few smokers can successfully quit the habit in their very first attempt. Many studies indicated that many smokers find it difficult to quit, even after they get afflicted with tobacco related diseases. A serious commitment and resolve is required to arrest nicotine dependency.

- In a growing number of countries, there are more ex-smokers than smokers.[2] (In the U.S. as of 2010, 47 million ex-smokers and 46 million smokers.)[3]

- Up to three-quarters of ex-smokers have quit without assistance (“cold turkey” or cut down then quit), and unaided cessation is by far the most common method used by most successful ex-smokers.[2]

- A serious attempt at stopping need not involve using nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or other drugs or getting professional support.[2]

- Early “failure” is a normal part of trying to stop. Many initial efforts are not serious attempts.[2]

- NRT, other prescribed pharmaceuticals, and professional counselling or support also help many smokers, but are certainly not necessary for quitting.[2]

Smoking addiction

Tobacco contains the chemical nicotine. Smoking cigarettes leads to a dependence on nicotine. Cessation of smoking leads to physiological symptoms of withdrawal.[citation needed] Methods of smoking cessation must address this dependency and subsequent withdrawal symptoms.

Methods of smoking cessation

Robert West and Saul Shiffman have authored works on smoking cessation. They believe that, used together, "behavioral support" and "medication" can quadruple the chances that a quit attempt will be successful. Both, however, disclosed that they are paid researchers or consultants to pharmaceutical companies or manufacturers of smoking cessation medications.[4]

Cold turkey

"Cold turkey" is abrupt cessation of all nicotine use. It is the quitting method used by 80%[5] to 90%[6] of long-term successful quitters in some populations. In a large British study of ex-smokers in the 1980s, before the advent of pharmacotherapy, 53% of the ex-smokers said that it was “not at all difficult” to stop, 27% said it was “fairly difficult”, and the remainder found it very difficult.[2] Methods advanced by J. Wayne McFarland and Elman J. Folkenburg (an M.D. and a pastor who wrote their Five Day Plan in about 1959),[7][8] Joel Spitzer and John R. Polito (smoking cessation educators whose work is free at WhyQuit.com)[9] and Allen Carr (who founded Easyway® during the early 1980s)[10] are cold turkey plans.

Cut down to quit

Gradual reduction involves slowly reducing one's daily intake of nicotine. This can be done in two ways: by repeated changes to cigarettes with lower levels of nicotine, or by gradually reducing the number of cigarettes smoked each day. As of 2010, and unlike earlier studies who claimed some benefit for gradual reduction, a Cochrane review found that abrupt cessation and gradual reduction with pre-quit NRT produced similar quit rates.[11]

Pharmacological

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved seven medications for treating nicotine addiction. All of these helped with withdrawal symptoms and cravings.

- Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) Five of the approved medications are different methods of delivering nicotine in a form that does not involve the risks of smoking. The five NRT medications, which Cochrane found in 1996 increased the chances of stopping smoking by 50 to 70% compared to placebo or to no treatment,[12] are:

- 1) transdermal nicotine patches deliver doses of the addictive chemical nicotine, thus reducing the unpleasant effects of nicotine withdrawal. These patches can give smaller and smaller doses of nicotine, slowly reducing dependence upon nicotine and thus tobacco. Cochrane found further increased chance of success in a combination of the nicotine patch and a faster acting form.[12] Also, this method becomes most effective when combined with other medication and psychological support.[13]

- 2) gum

- 3) lozenges

- 4) sprays

- 5) inhalers.

- A study found that 93 percent of over-the-counter NRT users relapse and return to smoking within six months.[14]

- Antidepressants: bupropion is an antidepressant marketed under the brand name Zyban.

Bupropion is contraindicated in epilepsy, seizure disorder; anorexia/bulimia (eating disorders), patients' use of antidepressant drugs (MAO inhibitors) within 14 days, patients undergoing abrupt discontinuation of ethanol or sedatives (including benzodiazepines such as Valium)[15] - Nicotinic receptor agonist: varenicline is a marketed by Pfizer in the U.S. as Chantix and Champix in the UK and Canada. Varenicline Tartrate is a prescription drug that can be used to alleviate some of the withdrawal symptoms. It can also be taken as a form of aversion therapy by smokers to make the act of smoking non-appealing or with adverse effects, similar to acamprosate or disulfiram for ethanol addiction.

- Cytisine (Tabex) is the basis of Pfizer's development of varenicline, and is an extremely inexpensive plant extract. It has been in use since the 1960s in former Soviet-bloc countries. It was the first medication approved as an aid to smoking cessation, and has very few side effects in small doses.[16][17] Pfizer funded and managed all studies of varenicline that were reviewed in a 2008 Cochrane review[18] and unfortunately as of 2009, Cochrane reports, "The evidence on cytisine is limited at present, and no firm conclusions can yet be drawn about its effectiveness as an aid to quitting."[19]

Two other medications have been used in trials for smoking cessation, although they are not approved by the FDA for this purpose. They may be used under careful physician supervision if the first line medications are contraindicated for the patient.[20]

- 1) Clonidine may reduce craving for cigarettes after cessation. However, it does not consistently ameliorate other withdrawal symptoms.

- 2) Nortriptyline, another antidepressant, has similar success rates to bupropion.[21]

Psychosocial approaches

- Great American Smokeout is an annual event that invites smokers to quit for one day, hoping they will be able to extend this forever.

- The World Health Organization's World No Tobacco Day is held on May 31 each year.

- Smoking-cessation support and counseling is often offered over the internet, over the phone quitlines (e.g. the US toll-free number 1-800-QUIT-NOW), or in person.

- Attending a self-help group such as Nicotine Anonymous[22] and electronic self-help groups such as Stomp It Out[23]

Smoking cessation services

Group or individual therapy can help people who want to quit. Some smoking cessation programs employ a combination of coaching, motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral therapy, and pharmacological counseling.

Self-help

- Interactive web-based programs which specialize in teaching participants how to quit.

- Quit meters: Small computer programs that keep track of quit statistics such as amount of "quit-time", cigarettes not smoked, and money saved.

- Self-help books such as Allen Carr's "Easy Way to Stop Smoking".

- Spirituality Spiritual beliefs and practices may help some smokers quit.[24]

- Newsgroups: dating back to Usenet days, alt.support.stop-smoking has been used by people quitting smoking as a place to go to for support from others. It is accessible through Google Groups.[25]

Substitutes for cigarettes

- Vaporizer: heats to 410 °F (210 °C) or less, compared with 1,500 °F (820 °C) in the tip of a cigarette when drawn upon; eliminates carbon monoxide and other combustion toxins.

- Electronic cigarette: Shaped like a cigar or cigarette, this device contains a rechargeable battery and a heating element that vaporizes liquid nicotine (and other flavorings) from an insertable cartridge, at lower initial cost than a vaporizer but with the same advantages including significantly reducing tar and carbon monoxide. However, in September 2008, the World Health Organization issued a release proclaiming that it does not consider the electronic cigarette to be a legitimate smoking cessation aid, stating that to its knowledge, "no rigorous, peer-reviewed studies have been conducted showing that the electronic cigarette is a safe and effective nicotine replacement therapy."[26]

- Smokeless tobacco: There is little smoking in Sweden, which is reflected in the low cancer rates for Swedish men. It is claimed that Swedish men are more likely to use snus (a form of steam-cured, rather than heat-cured, smokeless tobacco) than to smoke.[citation needed] There is a scientific debate over claims that spit tobacco might reduce the exposure of smokers to carcinogens or the risk for cancer (and even be used as a way to stop smoking). Some oral and spit tobaccos increase the risk for leukoplakia a precursor to oral cancer.[27] Chewing tobacco has been known to cause cancer, particularly of the mouth and throat.

- Smoking herb substitutions (non-tobacco).[28]

Alternative medical approaches

- Hypnosis clinical trials studying hypnosis as a method for smoking cessation have been inconclusive although many people have successfully quit smoking using hypnosis and hypnotherapy.

- Aromatherapy based treatments and herbal preparations [30] such as Kava and Chamomile, the efficacy of which has not been established. [citation needed]

- Acupuncture clinical trials have shown that acupuncture's effect on smoking cessation is equal to that of sham/placebo acupuncture. (See Cochrane Review)

- Laser therapy based on acupuncture principles but without the needles.

Intervention and Prevention

With adults:

- evidence-based interventions to help smokers quit

- policies making workplaces and public places smoke-free

- voluntary rules making homes smoke-free: "From 1992-1993 to 2003, increases occurred nationally and in every state in the percentage of households with complete smoke-free home rules (i.e., no one is allowed to smoke anywhere inside the home). During 1992-1993, the percentage of households with smoke-free home rules ranged from 25.7% in Kentucky to 69.6% in Utah. In 2003, the percentage ranged from 53.4% in Kentucky to 88.8% in Utah. The state with the smallest increase during this period was Utah, which had the highest prevalence of smoke-free home rules during 1992-1993. Kentucky, the state with the lowest prevalence of smoke-free home rules during 1992-1993, had the largest increase during this period."[31]

- initiatives to educate the public regarding the health effects of secondhand smoke, are needed to further reduce exposure of nonsmokers to secondhand smoke, as can be viewed in the surgeon general's report [1]

With children:

- youth anti-tobacco activities, such as sport involvement

- school-based curriculum, such as life-skills training [2]

- access reduction to tobacco

- anti-tobacco media [3] and [4]

- family communication: "The Current Population Survey (CPS) is a continuous monthly household survey administered by the U.S. Census Bureau for the Bureau of Labor Statistics that examines labor-force indicators for the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population aged 15 years. 2 Since 1992-1993, the National Cancer Institute has sponsored a Tobacco Use Supplement (TUS) to this survey with questions on tobacco use and related topics, including voluntary home smoking rules. CDC has cosponsored the supplement since 2001. The TUS-CPS was conducted in selected months during 1992-1993, 1995–1996, 1998–1999, 2000, 2001–2002, and 2003. Approximately 75% of respondents were contacted by telephone, and 25% of respondents were contacted by personal home visit. The supplement self-response rates for the TUS-CPS ranged from 65% in 2003 to 72% during 1992-1993.2* Data were adjusted for nonresponse and weighted using the household supplement self-response weight. This weight was calculated by summing the self-response weights for all respondents aged 15 years and dividing by the rostered number of persons aged 15 years to provide national and state prevalences of smoke-free home rules. Each household member aged 15 years was asked, 'Which statement best describes the rules about smoking inside your home?' The response options were (1) 'No one is allowed to smoke anywhere inside your home,' (2) 'Smoking is allowed in some places or at some times inside your home,' or (3) 'Smoking is permitted anywhere inside your home.'" [31]

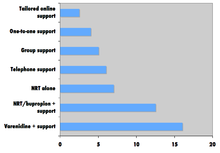

Comparison of success rates

The American Cancer Society (ACS) website says, "The truth is that quit smoking programs, like other programs that treat addictions, often have fairly low success rates." ACS says, "Success rates are hard to figure out for many reasons...not all programs define success in the same way."[33] The ACS says "that between about 25% and 33% of smokers who use medicines can stay smoke-free for over 6 months".[33] In 2010 the National Tobacco Cessation Collaborative (NTCC) created What Works to Quit: A Guide to Quit Smoking Methods, which compares the efficacy and cost of 17 smoking cessation methods. The guide, based on the 2008 Update to the Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence report, reports that smokers using a combination method of pharmacological and psychosocial approaches have the most success compared to those who use pharmaceutical or psychosocial approaches in isolation.[34]

Quitting can be harder for individuals with dark pigmented skin compared to individuals with pale skin since nicotine has an affinity for melanin-containing tissues. Studies suggest this can cause the phenomenon of increased nicotine dependence and lower smoking cessation rate in darker pigmented individuals.[35]

There is an important social component to smoking, which can be utilized by the counselors while advising the addicts. Study analyzing a densely interconnected network of over 12,000 individuals found that smoking cessation by any given individual reduced the chances of others around them lighting up by the following amounts: a spouse by 67%, a sibling by 25%, a friend by 36%, and a coworker by 34%.[36]

About 10% of people who quit unaided will remain non-smokers for 12 months.[37] Researchers at the University of Birmingham think about half of people who abstain for six months will maintain abstinence for the rest of their lives.[38]

Controlled trials

To determine the benefit or harm of a new therapy, ideally, a randomized controlled trial is usually conducted, a "gold standard" trial, as it is often called. In such a trial, one group of people are exposed to the treatment and another similar group is not. After some months or years have elapsed, mortality and morbidity in the two groups is compared. In the case of smoking cessation trials, the measures focus on rate of successful withdrawal, length of time in withdrawal and relapses.

Many people and organizations tout what are claimed to be effective methods of helping smokers to stop. Such claims of success are rarely backed up by independent comparative clinical trials or correctly calculated success rates. A separate thorough review of the evidence for each of several methods and aids for stopping smoking is available via the Cochrane Library website.[39]

Many such trials have been conducted to determine the health effects of quitting smoking although most have used quitting plus other lifestyle changes in diet and exercise, with or without drugs to improve blood pressure and blood cholesterol. The Cochrane Collaboration[40] have examined these trials and concluded that such interventions do not improve life expectancy or the death rate due to heart disease. They conclude that "Contrary to expectations, these lifestyle changes had little or no impact on the risk of heart attack or death" and "The continued enthusiasm for health promotion practices given the failure of these community intervention trials is curious, especially given the huge resources which have been put into them."

U.S. Clinical Practice Guideline

The U.S. government study of smoking cessation research is of limited use because it only followed up about 6 months after "quit day,"[41] and it did not examine evidence regarding unaided quit attempts.[2][42] The Guideline was published in 2000 called Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence[43] and updated in 2008 in the publication "Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update"[44] (to be called here the "Clinical Practice Guideline", or "2008 update" or simply "Guideline" report). Experts screened over 8700 research articles published between 1975 and 2007. More than 300 studies passed the criteria for the gold standard trials. Using these 300 studies for a meta-analysis of relevant treatments, it gives advice on smoking cessation treatment. An additional 600 reports were not included in the meta-analysis, but helped formulate the recommendations. In general:

- a) Control groups quit at a rate of around 10%.

- b) Pharmacological treatments resulted in 15-33% quit rates.

- d) Psychosocial interventions resulted in 14-25% quit rates.

- e) Little or no evidence was found to support use of hypnosis, acupuncture, or laser therapy as treatments for smoking cessation, alternate medicine or cigarette substitutes.

The following results are shown in Table 6.26 comparing placebo effect to pharmacological treatments.[citation needed] The Guideline followed up about 6 months after "quit day"[41] and did not examine evidence regarding unaided quit attempts.[42]

- The placebo quit rate for all of these comparisons was (13.8%) (table 6.26).

- All forms of drugs approved by the FDA for smoking cessation show more than twice the quit rate of the placebo group.

- The quit rate for using Varenicline(2 mg/day) (33.2%) as much as tripled over the placebo (13.8%) (Table 6.26). This was one of the highest quit rates for any single treatment. However, counter indications and adverse side effects might make it use undesirable for many smokers.

- Nicotine gum increased quit rate to 19%.

- All other FDA approved drugs alone increased quit rate about equally well (22.5-26.7%).

- Use of non-FDA approved, second line medications, did not significantly increase quit rates.

- The Nicotine Patch plus ad lib use of gum or spray increased quit rates to 36.5%, the largest quit rate reported in the study.

- The patch plus other FDA approved medications raised quit rates to between 25.8-28.9%.

- A physician's advice to quit can, significantly, increase quitting odds by 25 percent to (7.9% for no advise to 10.2% for advice. (Table 6.7) Not reported in the Guideline, several studies have found that smoking cessation advice is not always given in primary care in patients aged 65 and older,[45][46] despite the significant health benefits which can ensue in the older population.[47]

- Intensity of clinical intervention affects the degree of successful cessations.

- 1) Contact of 3 to 10 minutes can increase quit rate 60%. (Table 6.8)

- 2) Cessation programs involving more than 30 minutes of contact time increased success rates over no contact (11%) as much as 2 to almost 3 times (26% to 38.4%), regardless of other quitting method included (Table 6.9)

- Number of Sessions: Programs involving 8 or more treatment sessions can double success rates (24%) over 0 or 1 session (12%). (Table 6.10)

- Multiple formats of psychosocial interventions increase quit rates: 10% for no intervention, average 15.1% for one format, 18.5% for 2 formats, and 23.2% for three or four formats (Table 6.14).

- Self-help: Evidence did not support the efficacy of any self-help method (Table 6.15). The Authors advise more research on this in the future.

- Quitlines counseling significantly increased quit rate (12.7%) over self-help, minimal or no counseling (8.5%). Quitline counseling combined with medication (28.1%) also increased quit rate over medication alone (23.2%).

- Computerized Interventions (web-based or stand-alone) was identified in the Guideline report as having significant effects on quit rate, but no specifics were given.

- High intensity counseling of two or more sessions increased success rates to 27.6 to 32% when added to using any form of medication (Table 6.22, 6.23)

- The success rate of counseling alone (14.6%) was improved by adding use of medication to any counseling form (22.1%)

Side effects

Duration of nicotine withdrawal symptoms

| Craving for tobacco | Few days, up to months[48] |

| Dizziness | Few days[48] |

| Insomnia | 1 week[48] |

| Headaches | 1 to 2 weeks[48] |

| Chest discomfort | 1 to 3 weeks[48] |

| Constipation | 1 to 2 weeks[48] |

| Irritability | 2 to 4 weeks[48] |

| Fatigue | 2 to 4 weeks[48] |

| Cough or nasal drip | Few weeks[48] |

| Lack of concentration | Few weeks[48] |

| Hunger | Up to several weeks[48] |

Weight gain

Some studies have concluded that those who do successfully quit smoking may gain weight. "Weight gain is not likely to negate the health benefits of smoking cessation, but its cosmetic effects may interfere with attempts to quit." (Williamson, Madans et al., 1991). Therefore, drug companies researching smoking-cessation medication often measure the weight of the participants in the study. In 2009, it was found that smoking over expresses the gene AZGP1 which stimulates lipolysis, which is the possible reason why smoking cessation leads to weight gain.[49] Ex-smokers have to overcome the fact that nicotine is an appetite suppressant. Also, heavy smokers burn 200 calories per day more than non-smokers eating the same diet.[50]

Depression

In the case of many adults,but more especially women, a major hurdle for quitting may emanate from clinical depression and challenge smoking cessation. Quitting smoking is especially difficult during certain phases of the reproductive cycle, phases that have also been associated with greater levels of dysphoria, and subgroups of women who have a high risk of continuing to smoke also have a high risk of developing depression. Since many women who are depressed may be less likely to seek formal cessation treatment, practitioners have a unique opportunity to persuade their patients to quit.[51]

Health benefits

The immediate effects of smoking cessation include:[52]

- Within 20 minutes, blood pressure decreases, pulse returns to its normal level

- After 8 hours, carbon monoxide levels in the blood return to normal, oxygen level increases

- After 24 hours, chance of heart attack starts to decrease; breath, hair and body stop smelling like smoke

- After 48 hours, damaged nerve endings begin to recover; sense of taste and smell improve

- After 72 hours, the body is virtually free of nicotine; bronchial tubes relax, breathing becomes easier

- After 2–12 weeks, lungs can hold more air, exercise becomes easier and circulation improves

Longer-term effects include:[52]

- After 1 year, the risk of coronary heart disease is cut in half

- After 5 years, the risk of stroke falls to the same as a non-smoker

- After 10 years, the risk of lung cancer is cut in half and the risk of other cancers decreases significantly

- After 15 years, the risk of coronary heart disease drops, usually to the level of a non-smoker

Many of tobacco's health effects can be minimized through smoking cessation. The British doctors study[53] showed that those who stopped smoking before they reached 30 years of age lived almost as long as those who never smoked. Smoking cessation will almost always lead to a longer and healthier life. Stopping in early adulthood can add up to 10 years of healthy life and stopping in one's sixties can still add three years of healthy life (Doll et al., 2004). Stopping smoking is associated with better mental health and spending less of one's life with diseases of old age.

Some research has indicated that some of the damage caused by smoking tobacco can be moderated with the use of antioxidants.[54]

Upon smoking cessation, the body begins to rid itself of foreign substances introduced through smoking. These include substances in the blood such as nicotine and carbon monoxide, and also accumulated particulate matter and tar from the lungs. As a consequence, though the smoker may begin coughing more, cardiovascular efficiency increases.

Many of the effects of smoking cessation can be seen as landmarks, often cited by smoking cessation services, by which a smoker can encourage himself to keep going. Some are of a certain nature, such as those of nicotine clearing the bloodstream completely in 48 to 72 hours, and cotinine (a metabolite of nicotine) clearing the bloodstream within 10 to 14 days. Other effects, such as improved circulation, are more variable in nature, and as a result less definite timescales are often cited.

See also

- Allen Carr

- American Legacy Foundation

- Carbon monoxide breath monitor

- Coerced abstinence

- Bijan Daneshmand

- Electronic cigarette

- Health promotion

- Herbal tobacco alternatives

- [Hypnosis Stop Smoking]

- List of smoking bans in the United States

- Massachusetts Tobacco Cessation and Prevention Program (MTCP)

- National Tobacco Cessation Collaborative

- Nicotine Anonymous

- Nicotine replacement therapy

- NicVAX

- Smoking cessation (cannabis)

- Smoking cessation programs in Canada

- [Stop Smoking Today]

- Joel Spitzer

- Tobacco and health

- Tobacco cessation clinic

- U.S. government and smoking cessation

- Youth Tobacco Cessation Collaborative

- Withdrawal Smoking

Notes

- ^ "Guide to Quitting Smoking". American Cancer Society. 2009-10-01. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chapman, Simon and MacKenzie, Ross (February 9, 2010). "The Global Research Neglect of Unassisted Smoking Cessation: Causes and Consequences". PLoS Medicine. 7 (2). Public Library of Science: e1000216. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000216. PMC 2817714. PMID 20161722.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Martin, Anya (May 13, 2010). "What it takes to quit smoking". Marketwatch. Dow Jones. p. 2. Retrieved May 14, 2010.

- ^ West & Shiffman, pp. 73, 76, 80

- ^ Doran CM, Valenti L, Robinson M, Britt H, Mattick RP. Smoking status of Australian general practice patients and their attempts to quit. Addict Behav. 2006 May;31(5):758-66. PMID 16137834

- ^ American Cancer Society. "Cancer Facts & Figures 2003" (PDF).

- ^ "New book details history of LLU bringing 'Health to the People'". Loma Linda University. March 31, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ McFarland, J. Wayne and Folkenberg, Elman J. (1964). "The Five-Day Plan to Quit Smoking" (PDF). University Health Services, University of Wisconsin. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "WhyQuit". WhyQuit. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "Allen Carr Worldwide". Allen Carr. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ Joseph, Jennifer (March 30, 2010). "Cut down to quit approach no better". Pharmacy News. Reed Business Information. and Lindson N, Aveyard P, Hughes JR (2010). "Reduction versus abrupt cessation in smokers who want to quit". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 3 (3). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Art. No.: CD008033: CD008033. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008033.pub2. PMID 20238361. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Stead LF, Perera R, Bullen C, Mant D, Lancaster T. (2008). "Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Art. No.: CD000146. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub3. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Noble, Holcomb B. (March 2, 1999). "New From the Smoking Wars: Success". The New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ Millstone, Ken (February 13, 2007). "Nixing the patch: Smokers quit cold turkey". Columbia.edu News Service. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ Charles F. Lacy et al., LEXI-COMP'S Drug Information Handbook 12th edition. Ohio, USA,2004

- ^ Herrick, Charles and Mitchell, Marianne (2009). 100 Questions & Answers About How to Quit Smoking. Jones & Bartlet. p. 112. ISBN 0763757411.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ West & Shiffman, p. 70

- ^ Phend, Crystal (January 24, 2007). "Nicotine-Receptor Partial Agonist Found Better Butt-Beater". MedPage Today. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ Cahill K, Stead LF, Lancaster T (2008). "Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation". No. 3. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Art. No.: CD006103. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub3. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ American Cancer Society. "Cancer Facts & Figures 2003" (PDF).

- ^ West & Shiffman, p.70

- ^ "Nicotine Anonymous: A 12 Step Program".

- ^ "Experience Project: Stomp it Out".

- ^ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/05/070507154054.htm

- ^ http://groups.google.ca/group/alt.support.stop-smoking/

- ^ "Marketers of electronic cigarettes should halt unproved therapy claims". World Health Organization. 2008-09-19. Retrieved 2008-10-01.

- ^ Detailed Guide: Cancer (General Information) Signs and Symptoms of Cancer http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_3X_What_are_the_signs_and_symptoms_of_cancer.asp

- ^ http://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/Smoking_cessation#Herbal_alternatives

- ^ Naqvi NH, Rudrauf D, Damasio H, Bechara A. Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking. New stop smoking therapies may be based on this.Science. 2007 Jan 26;315(5811):531-4.PMID 17255515

- ^ Salley, Danielle (2010-06-23). "Green Ways to Quit Smoking". Four Green Steps.

- ^ a b (2007).State-Specific Prevalence of Smoke-Free Home Rules—United States, 1992-2003, Vol. 298(2), 169-170.

- ^ West & Shiffman, p. 59

- ^ a b "Guide to Quitting Smoking". The American Cancer Society. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- ^ "What Works To Quit" (PDF). The National Tobacco Cessation Collaborative. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ^ King G, Yerger VB, Whembolua GL, Bendel RB, Kittles R, Moolchan ET. Link between facultative melanin and tobacco use among African Americans.(2009). Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 92(4):589-96. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2009.02.011 PMID 19268687

- ^ Fratiglioni L, Wang HX (2008). "The collective dynamics of smoking in a large social network". N Engl J Med. 358 (21): 2249–58. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0706154. PMC 2822344. PMID 18499567.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sutherland, Gay (May 16, 2005). "Methods for quitting". NetDoctor. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ Phend, Crystal (April 3, 2000). "Gradual Cutback with Nicotine Replacement Boosts Quit Rates". MedPage Today. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ Cochrane Topic Review Group: Tobacco Addiction

- ^ http://mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD001561/pdf_fs.html

- ^ a b "Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence:2008 Update" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. May 2008. p. 23.

- ^ a b "Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence:2008 Update" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. May 2008. p. 9.

- ^ "Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. June 2000.

- ^ "Clinical Practice Guideline: Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence:2008 Update" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. May 2008.

- ^ Maguire CP, Ryan J, Kelly A, O'Neill D, Coakley D, Walsh JB. Do patient age and medical condition influence medical advice to stop smoking? Age Ageing. 2000 May;29(3):264-6. PMID 10855911

- ^ Ossip-Klein DJ, McIntosh S, Utman C, Burton K, Spada J, Guido J. Smokers ages 50+: who gets physician advice to quit? Prev Med. 2000 Oct;31(4):364-9. PMID 11006061

- ^ Ferguson J, Bauld L, Chesterman J, Judge K. The English smoking treatment services: one-year outcomes. Addiction. 2005 Apr;100 Suppl 2:59-69. PMID 15755262

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of the Northwest (2008). Cultivating Health: Freedom From Tobacco Kit. Kaiser Permanente. ISBN 978-0-9744864-8-2.

- ^ Vanni, H; Kazeros, A; Wang, R; Harvey, BG; Ferris, B; De, BP; Carolan, BJ; Hübner, RH; O'Connor, TP (2009). "Cigarette Smoking Induces Over expression of a Fat-Depleting Gene AZGP1 in the Human". Chest. 135 (5): 1197–208. doi:10.1378/chest.08-1024. PMC 2679098. PMID 19188554.

- ^ Johns Hopkins University (1998). The Johns Hopkins Family Health Book. William Morrow. p. 86. ISBN 0062701495.

- ^ The impact of depression on smoking cessation in women.

- ^ a b Quit Smoking for Good: The Take Control Guide. Tobacco Education Clearinghouse of California, Regents of the University of California. 2001.

- ^ Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I (2004). "Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors". BMJ. 328 (7455): 1519. doi:10.1136/bmj.38142.554479.AE. PMC 437139. PMID 15213107.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Panda K, Chattopadhyay R, Chattopadhyay DJ, Chatterjee IB (2000). "Vitamin C prevents cigarette smoke-induced oxidative damage in vivo". Free Radic. Biol. Med. 29 (2): 115–24. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(00)00297-5. PMID 10980400.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

- Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. Bmj 2004;328(7455):1519.

- Helgason AR, Tomson T, Lund KE, Galanti R, Ahnve S, Gilljam H. Factors related to abstinence in a telephone helpline for smoking cessation. European J Public Health 2004: 14;306-310.

- Henningfield J, Fant R, Buchhalter A, Stitzer M (2005). "Pharmacotherapy for nicotine dependence". CA Cancer J Clin. 55 (5): 281–99, quiz 322–3, 325. doi:10.3322/canjclin.55.5.281. PMID 16166074.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Full text - Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 2004;99(1):29-38.

- Hutter H.P. et al. Smoking Cessation at the Workplace:1 year success of short seminars. International Archives of Occupational & Environmental Health. 2006;79:42-48.

- Marks, D.F. The QUIT FOR LIFE Programme:An Easier Way To Quit Smoking and Not Start Again. Leicester: British Psychological Society. 1993.

- Marks, D.F. & Sykes, C. M. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy for smokers living in a deprived area of London: outcome at one-year follow-up

Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2005;7:17-24.

- Marks, D.F. Overcoming Your Smoking Habit. London: Robinson.2005.

- Peters MJ, Morgan LC. The pharmacotherapy of smoking cessation. Med J Aust 2002;176:486-490. Fulltext. PMID 12065013.

- Silagy C, Lancaster T, Stead L, Mant D, Fowler G. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(3):CD000146.

- USDHHS. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research Quality; 2000.

- West R. Tobacco control: present and future. Br Med Bull 2006;77-78:123-36.

- West, Robert and Shiffman, Saul (2007). Fast Facts: Smoking Cessation (2 ed.). Health Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1-903734-98-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Williamson, DF, Madans, J, Anda, RF, Kleinman, JC, Giovino, GA, Byers, T Smoking cessation and severity of weight gain in a national cohort N Engl J Med 1991 324: 739-745

- World Health Organization, Tobacco Free Initiative

- Zhu S-H, Anderson CM, Tedeschi GJ, et al. Evidene of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quitline$for smokers. N Engl J Med 2002;347(14):1087-93.

- Williams LN , “Oral Health is Within REACH”, Navy Medicine, Mar-Apr 2001

- Williams LN, “Tobacco Cessation: An Access to Care Issue”, Navy Medicine, 2002

External links

A blog of a smokers attempt to quit using the "Cold Turkey" method.