Spinozism

This article needs attention from an expert on the subject. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. (January 2011) |

| Part of the series on Modern scholasticism | |

| |

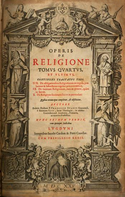

| Title page of the Operis de religione (1625) from Francisco Suárez. | |

| Background | |

|---|---|

|

Protestant Reformation | |

| Modern scholastics | |

|

Second scholasticism of the School of Salamanca | |

| Reactions within Christianity | |

|

The Jesuits against Jansenism | |

| Reactions within philosophy | |

|

Neologists against Lutherans | |

Spinozism is the Dualist Pantheism system of Baruch Spinoza. As with all variants of Dualist Pantheism it defines "God" to be equivalent to the Universe (Nature) and both matter and thought as attributes of it.

Categorisation

Spinoism is commonly associated with Pantheism although the term had not even been coined until after Spinoza's life. Since God unifies the mind and matter it can be thought of as a monist philosophy. Although, there are clear divisions between minad and matter so the categorization of dualism is more common. It is defined as Dualist Pantheism essentially because neither the claim of idealism required for Monist idealist Pantheism nor the claim of philosophical realism required for Monist Physicalist Pantheism is supported.

Core Doctrine

Spinoza's doctrine was considered radical at the time he published and he was widely seen as the most infamous atheist-heretic of Europe. His philosophy was part of the philosophic debate in Europe during the Enlightenment, along with Cartesianism.

In Spinozism, the concept of a personal relationship with God comes from the position that one is a part of an infinite interdependent "organism". Spinoza taught that everything is but a wave in an endless ocean, and that what happens to one wave will affect other waves. Thus Spinozism teaches a form of determinism and ecology and supports this as a basis for morality.[citation needed]

Additionally, a core doctrine of Spinozism is that the universe is essentially deterministic. All that happens or will happen could not have unfolded in any other way. Spinozism is closely related to the Hindu doctrines of Samkhya and Yoga. [citation needed] Spinoza claimed that the third kind of knowledge, intuition, is the highest kind attainable.

Spinoza's metaphysics consists of one thing, substance, and its modifications (modes). Early in The Ethics Spinoza argues that there is only one substance, which is absolutely infinite, self-caused, and eternal. He calls this substance "God", or "Nature". In fact, he takes these two terms to be synonymous (in the Latin the phrase he uses is "Deus sive Natura"). For Spinoza the whole of the natural universe is made of one substance, God, or, what's the same, Nature, and its modifications (modes).

It cannot be overemphasized how the rest of Spinoza's philosophy—his philosophy of mind, his epistemology, his psychology, his moral philosophy, his political philosophy, and his philosophy of religion—flows more or less directly from the metaphysical underpinnings in Part I of the Ethics.[1]

Substance

Spinoza defines "substance" as follows:

By substance I understand what is in itself and is conceived through itself, i.e., that whose concept does not require the concept of another thing, from which it must be formed.(E1D3)[2]

This means, essentially, that substance is just whatever can be thought of without relating it to any other idea or thing. For example, if one thinks of a particular object, one thinks of it as a kind of thing, e.g., x is a cat. Substance, on the other hand, is to be conceived of by itself, without understanding it as a particular kind of thing (because it isn't a particular thing at all).

Attributes

Spinoza defines "attribute" as follows:

By attribute I understand what the intellect perceives of a substance, as constituting its essence.(E1D4)[2]

From this it can be seen that attributes are related to substance in some way. It is not clear, however, even from Spinoza's direct definition, whether, a) attributes are really the way(s) substance is, or b) attributes are simply ways to understand substance, but not necessarily the ways it really is. Spinoza thinks that there are an infinite number of attributes, but there are two attributes for which Spinoza thinks we can have knowledge. Namely, thought and extension.[3]

Thought

The attribute of thought is how substance can be understood to be composed of thoughts, i.e., thinking things. When we understand a particular thing in the universe through the attribute of thought, we are understanding the mode as an idea of something (either another idea, or an object).

Extension

The attribute of extension is how substance can be understood to be physically extended in space. Particular things which have breadth and depth (that is, occupy space) are what is meant by extended. It follows from this that if substance and God are identical, on Spinoza's view, and contrary to the traditional conception, God has extension as one of his attributes.

Modes

Modes are particular modifications of substance, i.e., particular things in the world. Spinoza gives the following definition:

By mode I understand the affections of a substance, or that which is in another through which it is also conceived.(E1D5)[2]

Substance monism

The argument for there only being one substance (or, more colloquially, one kind of stuff) in the universe occurs in the first fourteen propositions of The Ethics. The following proposition expresses Spinoza's commitment to substance monism:

Except God, no substance can be or be conceived.(E1P14)[2]

Spinoza takes this proposition to follow directly from everything he says prior to it. Spinoza's monism is contrasted with Descartes' dualism and Leibniz's pluralism. It allows Spinoza to avoid the problem of interaction between mind and body, which troubled Descartes in his Meditations on First Philosophy.

Causality and modality

The issue of causality and modality (possibility and necessity) in Spinoza's philosophy is contentious.[4] Spinoza's philosophy is, in one sense, thoroughly deterministic (or necessitarian). This can be seen directly from Axiom 3 of The Ethics:

From a given determinate cause the effect follows necessarily; and conversely, if there is no determinate cause, it is impossible for an effect to follow.(E1A3)[2]

Yet Spinoza seems to make room for a kind of freedom, especially in the fifth and final section of The Ethics, "On the Power of the Intellect, or on Human Freedom":

I pass, finally, to the remaining Part of the Ethics, which concerns the means or way, leading to Freedom. Here, then, I shall treat of the power of reason, showing what it can do against the affects, and what Freedom of Mind, or blessedness, is.(E5, Preface)[2]

So Spinoza certainly has a use for the word 'freedom', but he equates "Freedom of Mind" with "blessedness", a notion which is not traditionally associated with freedom of the will at all.

The principle of sufficient reason (PSR)

Though the PSR is most commonly associated with Gottfried Leibniz, it is arguably found in its strongest form in Spinoza's philosophy.[5] Within the context of Spinoza's philosophical system, the PSR can be understood to unify causation and explanation.[6] What this means is that for Spinoza, questions regarding the reason why a given phenomenon is the way it is (or exists) are always answerable, and are always answerable in terms of the relevant cause(s). This constitutes a rejection of teleological, or final causation, except possibly in a more restricted sense for human beings.[2][6] Given this, Spinoza's views regarding causality and modality begin to make much more sense.

Parallelism

Spinoza's philosophy contains as a key proposition the notion that mental and physical (thought and extension) phenomena occur in parallel, but without causal interaction between them. He expresses this proposition as follows:

The order and connection of ideas is the same as the order and connection of things.(E2P7)[2]

His proof of this proposition is that:

The knowledge of an effect depends on, and involves, the knowledge of its cause.(E1A4)[2]

The reason Spinoza thinks the parallelism follows from this axiom is that since the idea we have of each thing requires knowledge of its cause, and this cause must be understood under the same attribute. Further, there is only one substance, so whenever we understand some chain of ideas of things, we understand that the way the ideas are causally related must be the same as the way the things themselves are related, since the ideas and the things are the same modes understood under different attributes.

Sources

- Jonathan I. Israel. Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity, 1650-1750. 2001.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)