Painted turtle

| Painted turtle | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Scientific classification | |||||

| Kingdom: | |||||

| Phylum: | |||||

| Class: | |||||

| Order: | |||||

| Family: | |||||

| Subfamily: | |||||

| Genus: | Chrysemys Gray, 1844

| ||||

| Species: | C. picta

| ||||

| Binomial name | |||||

| Chrysemys picta (Schneider, 1783)

| |||||

| Subspecies | |||||

|

C. p. bellii [2] | |||||

| Synonyms | |||||

| |||||

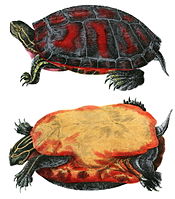

The painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) is the only species of Chrysemys, a genus of Emydidae: the pond turtle family. It lives in slow-moving fresh waters, from southern Canada to Louisiana and northern Mexico, and from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. Fossils show that the painted turtle existed 15 million years ago, but four regionally based subspecies (the eastern, midland, southern and western) evolved during the last ice age. The painted turtle is 10–25 cm (4–10 in) long and weighs 300–500 g (11–18 oz); females are larger than males. Its shell is smooth, oval, and flat-bottomed. Its skin is olive to black with red, orange, or yellow stripes on its extremities.

The painted turtle eats aquatic vegetation, algae, and small water creatures including insects, crustaceans, and fish. Although they are frequently consumed as eggs or hatchlings by rodents, canines, and snakes, the adult turtles' hard shells protect them from most predators except alligators and raccoons.

Reliant on warmth from its surroundings, the painted turtle is active only during the day, when it basks for hours on logs or rocks. During winter, the turtle hibernates, usually in the muddy bottoms of waterways. The turtles mate in spring and autumn; between late spring and mid-summer females dig nests on land and lay their eggs. Hatched turtles grow until sexual maturity: 2–9 years for males, 6–16 for females. Adults in the wild can live for more than 55 years.

In the traditional tales of Algonquian tribes, the colorful turtle played the part of a trickster. The painted turtle is the United State's second most popular pet turtle, although trapping is increasingly restricted. Habitat loss and road killings have also reduced the turtle's population, but its ability to live in human-disturbed settings has helped it remain the most abundant turtle in North America. Only in Oregon and British Columbia is its range in danger of being encroached upon. Perhaps because it is so widespread, four US states name the painted turtle as their official reptile.

Taxonomy and evolution

The painted turtle (C. picta) is the only species in the genus Chrysemys.[4] The parent family for Chrysemys is Emydidae: the pond turtles. The Emydidae family is split into two sub families; Chrysemys is part of the Deirochelyinae (Western Hemisphere) branch.[5] The four subspecies of the painted turtle are the eastern (C. p. picta), midland (C. p. marginata), southern (C. p. dorsalis), and western (C. p. bellii).[6]

Originally described in 1783 by Johann Gottlob Schneider as Testudo picta,[4][7] the painted turtle was called Chrysemys picta first by John Edward Gray in 1844.[8][9] The four subspecies were then recognized: the eastern by Schneider in 1783,[7][10] the western by Gray in 1831,[10][11] and the midland and southern by Louis Agassiz in 1857.[12][13] The painted turtle's generic name is derived from the Ancient Greek words for "gold" (chryso) and "freshwater tortoise" (emys); the species name originates from the Latin for "colored" (pictus).[14] The subspecies name, marginata, derives from the Latin for "border", and refers to the red markings on the outer (marginal) part of the upper shell; dorsalis is from the Latin for "back", referring to the prominent dorsal stripe; and bellii honored zoologist Thomas Bell, a collaborator of Charles Darwin.[15] An alternate East Coast common name for the painted turtle is "skilpot", from the Dutch for turtle, schildpad.[16]

Although its evolutionary history—what the forerunner to the species was and how the close relatives branched off—is not well understood, the painted turtle is common in the fossil record.[17] The oldest samples, found in Nebraska, date to about 15 million years ago. Fossils from 15 million to about 5 million years ago are restricted to the Nebraska–Kansas area, but more recent fossils are gradually more widely distributed. Fossils newer than 300,000 years old are found in almost all the United States and southern Canada.[1]

Biologists have long debated the classification of closely related subfamily-mates Chrysemys, Pseudemys (cooters), and Trachemys (sliders). After 1952, some combined Pseudemys and Chrysemys because of similar appearance.[18] In 1964, based on measurements of the skull and feet, Samuel B. McDowell proposed the three genera be merged into one with each representing a subspecies, but further measurements, in 1967, contradicted this taxonomic arrangement. Also in 1967, J. Alan Holman,[19] a paleontologist and herpetologist, pointed out that, although the three turtles were often found together in nature and had similar mating patterns, they did not crossbreed. In the 1980s, studies of turtles' cell structures, biochemistries, and parasites further indicated that Chrysemys, Pseudemys, and Trachemys should remain in separate genera.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

Taxonomic controversy has also surrounded the subspecies. Until 1931 many of the subspecies of painted turtle were labeled by biologists as full species within Chrysemys, but even this varied by the individual. The painted turtles in the border region between the western and midland subspecies were even considered a full species, treleasei. The current "four in one" taxonomy of species and subspecies was first established in 1931 by Bishop and Schmidt. Based on comparative measurements of turtles from throughout the range, they subordinated several species to subspecies and eliminated treleasei.[20]

Since at least 1958,[21][nb 2] the subspecies were thought to have evolved in response to geographic isolation during the last ice age, 100,000 to 11,000 years ago.[22] At that time painted turtles were divided into three different populations: eastern painted turtles along the southeastern Atlantic coast; southern painted turtles around the southern Mississippi River; and western painted turtles in the southwestern United States.[23] The populations were not completely isolated for sufficiently long, hence wholly different species never evolved. When the glaciers retreated, about 11,000 years ago, all three subspecies moved north. The western and southern subspecies met in Missouri and hybridized to produce the midland painted turtle, which then settled the Tennessee River basin, across the Mississippi.[21][23]

David E. Starkey and collaborators advanced a new view of the subspecies in 2003. Based on a study of the mitochondrial DNA, they rejected the glacial development theory and argued that the southern painted turtle should be elevated to a separate species, C. dorsalis, while the other subspecies should be collapsed into one and not differentiated.[24] However, this proposition was largely unrecognized[10] because successful breeding between all subspecies was documented wherever they overlapped.[10][25] Nevertheless, in 2010, the IUCN recognized both C. dorsalis and C. p. dorsalis as valid names for the southern painted turtle.[2]

Description

The painted turtle's shell is 10–25 cm (4–10 in) long,[26][nb 3] oval, smooth, and flat-bottomed.[27][28] The color of the top shell (carapace) varies from olive to black, allowing the turtle to blend in with its surroundings.[29] The bottom shell (plastron) is yellow, sometimes red, sometimes with dark markings in the center.[30] Similar to the top shell, the turtle's skin is olive to black, but with red and yellow stripes on its neck, legs, and tail.

The head of the turtle is distinctive. The face has only yellow stripes,[26][28] with a large yellow spot and streak behind each eye,[28] and on the chin two wide yellow stripes that meet at the tip of the jaw.[29] The turtle's upper jaw is shaped into an inverted "V" (philtrum), with a downward-facing, tooth-like projection on each side.[31] Like many other closely related pond turtles, such as the bog turtle,[32][33] the painted turtle has webbed feet to aid its swimming.[34]

The hatchling has a proportionally smaller head, eyes, and tail,[35] and a more circular shell than the adult.[36] The female is larger than the male, 10–25 cm (4–10 in) versus 7–15 cm (3–6 in) long.[29][37] The male has much longer foreclaws and a slightly longer, thicker tail.[26][27][28]

Although the subspecies may hybridize (intergrade), especially at range boundaries,[38] they are distinct within the hearts of their ranges.[39] The turtle's karyotype consists of 50 chromosomes.[28]

The male eastern painted turtle (C. p. picta) is 13–17 cm (5–7 in) long, while the female is 14–17 cm (6–7 in). The upper shell is olive green to black and may possess a pale stripe down the middle and red markings on the periphery. The segments (scutes) of the top shell have pale leading edges and occur in straight rows across the back, unlike all other North American turtles, including the other three subspecies of painted turtle, which have alternating segments.[39] The bottom shell is plain yellow or lightly spotted.[40]

The midland painted turtle (C. p. marginata) is 10–25 cm (4–10 in) long.[41] The centrally located midland is the hardest to distinguish from the other three subspecies.[39] Its bottom shell has a characteristic symmetrical dark shadow in the center which varies in size and prominence.[23]

The southern painted turtle (C. p. dorsalis), the smallest subspecies, is 10–14 cm (4–6 in) long.[42] Its top stripe is a prominent red,[39] and its bottom shell is tan and spotless or nearly so.[43]

The largest subspecies is the western painted turtle (C. p. bellii), which grows up to 25 cm (10 in) long.[44] Its top shell has a mesh-like pattern of light lines,[22] and the top stripe present in other subspecies is missing or faint. Its bottom shell has a large colored splotch that spreads to the edges (further than the midland) and often has red hues.[22]

Distribution

Range

The painted turtle is the only North American turtle whose native range extends from the Atlantic to the Pacific. On the East Coast, it lives from the Canadian Maritimes to Georgia. On the West Coast, it lives in British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon[22] and offshore on southeast Vancouver Island.[45][nb 4] The northernmost American turtle,[45] its range includes southern Canada. To the south, its range reaches the US Gulf Coast in Louisiana. In the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, there are only dispersed populations.[26]

The borders between the four subspecies are not sharp, because the subspecies interbreed. Many studies have been performed in the border regions to assess the intermediate turtles, usually by comparing the anatomical features of the hybrids to those of the classical subspecies.[nb 5] Despite the imprecision, the subspecies are assigned nominal ranges.[26]

The eastern painted turtle ranges from southeastern Canada (Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, excepting Prince Edward Island) to Georgia. The western extent of its range is approximately the Appalachians.[26][49]

The midland painted turtle lives from southern Ontario and Quebec, through the eastern US Midwest states, to Tennessee and Alabama. It also is found eastward through Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, North and South Carolina, Maryland, and into New England, where it may overlap the eastern painted turtle's range.[26][43] The midland painted turtle appears to be moving eastward, especially in Pennsylvania.[50]

The southern painted turtle ranges from southern Illinois and Missouri, roughly along the Mississippi River, to the south. In Arkansas, it branches out to the west towards Texas, where it is found in the northeast part of that state (Caddo Lake region)[51] as well as extreme southeastern Oklahoma (McCurtain County).[52] It is found in all of Louisiana, where it reaches the Gulf of Mexico but is not found on the rest of the Gulf Coast. East of Louisiana, it covers most of Mississippi and extends well into Alabama.[26][43][53]

The western painted turtle's range spans from Ontario and British Columbia to the central and western United States. Its western boundary reaches the Pacific in Washington, northern Oregon, and southern British Columbia. To the southwest, it is found in scattered areas.[26] In Arizona, the painted turtle is native to an area in the north, Lyman Lake.[54] In New Mexico, distribution follows the Rio Grande and the Pecos River, two waterways that run in a north-south direction through the state.[55] Within the aforementioned rivers, it is also found in the northern part of far western Texas.[51] In Mexico,[55] painted turtles have been found about 50 miles south of New Mexico near Galeana in the state of Chihuahua. There, two expeditions[56][57] found the turtles only in the Rio Santa Maria which is in a closed basin.[22][26][58]

Pet releases are starting to establish the painted turtle outside its native range. In California, it is an invasive species that endangers the local western pond turtle, although competition from similarly released red-eared sliders is a greater threat.[59] It has also been introduced into waterways near Phoenix, Arizona,[54] and to Germany, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Spain.[2]

Habitat

To thrive, painted turtles need fresh waters with soft bottoms, basking sites, and aquatic vegetation. They find their homes in shallow waters with slow-moving currents, such as creeks, marshes, ponds, and the shores of lakes. Along the Atlantic, painted turtles have appeared in brackish waters.Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page).

The four subspecies have evolved different habitat preferences. The eastern painted turtle is very aquatic, leaving the immediate vicinity of its water body only when forced by drought to migrate.[60] The midland and southern painted turtles seek especially quiet waters, usually shores and coves. They favor shallows that contain dense vegetation and have an unusual toleration of pollution.[42][61] The western painted turtle lives in streams and lakes, similar to the other painted turtles, but also inhabits pasture ponds and roadside pools. It is found as high as 1,800 m (5,900 ft).[44]

Population features

Within much of its range, the painted turtle is the most abundant turtle species. Population densities range from 10 to 840 turtles per hectare (2.5 acres) of water surface. Warmer climates produce higher relative densities among populations, and habitat desirability also influences density. Rivers and large lakes have lower densities because only the shore is desirable habitat; the central, deep waters skew the surface-based estimates. Also, lake and river turtles have to make longer linear trips to access equivalent amounts of foraging space.[62]

Adults outnumber juveniles in most populations, but gauging the ratios is difficult because juveniles are harder to catch; with current sampling methods, estimates of age distribution vary widely.[63] Annual survival rate of painted turtles increases with age. The probability of a painted turtle surviving from the egg to its first birthday is only 19%. For females, the annual survival rate rises to 45% for juveniles and 95% for adults. The male survival rates follow a similar pattern, but are lower overall than females, creating an average male age lower than that of the female.[64] Natural disasters can confound age distributions. For instance, a hurricane can destroy many nests in a region, resulting in fewer hatchlings the next year.[64] Age distributions may also be skewed by migrations of adults.[63]

To understand painted turtle adult age distributions, researchers require reliable methods.[65] Turtles younger than four years (up to 12 years in some populations) can be aged based on "growth rings" in their shells.[66] For older turtles, some attempts have been made to determine age based on size and shape of their shells or legs using mathematical models, but this method is more uncertain.[66][67] The most reliable method to study the long-lived turtles is to capture them, permanently mark their shells by notching with a drill, release the turtles, and then recapture them in later years.[68] The longest-running study, in Michigan, has shown that painted turtles can live more than 55 years.[66][69]

Adult sex ratios of painted turtle populations average around 1:1.[70] Many populations are slightly male-heavy, but some are strongly female-imbalanced; one population in Ontario has a female to male ratio of 4:1.[71] Hatchling sex ratio varies based on egg temperature. During the middle third of incubation, temperatures of 23–27 °C (73–81 °F) produce males, and anything above or below that, females.[72] It does not appear that females choose nesting sites to influence the sex of the hatchlings;[35] within a population, nests will vary sufficiently to give both male and female-heavy broods.[63]

Ecology

Diet

The painted turtle hunts along water bottoms. It quickly juts its head into and out of vegetation to stir potential victims out into the open water, where they are pursued.[73] Large prey it holds in its mouth and tears up with its forefeet. It also consumes plants and skims the surface of the water with its mouth open to catch small particles of food.[73] Although all subspecies of painted turtle eat plants and animals, either alive or dead, their tendencies vary.[73][74]

The eastern painted turtle's diet is the least studied. It prefers to eat in the water, but has been observed eating on land. The fish it consumes are typically dead or injured.[74]

The midland painted turtle eats mostly aquatic insects and both vascular and non-vascular plants.[75]

The southern painted turtle's diet changes with age. Juveniles have a 13% vegetarian diet, adults 88%. This perhaps shows the turtle prefers meat, but can only obtain the amounts desired (by eating small larvae and such) while young.[76] The reversal of feeding habits with age has also been seen in the false map turtle, which inhabits some of the same range. The most common plants eaten by adult southern painted turtles are duckweed and algae, and the most common prey items are dragonfly larvae and crayfish.[77]

The western painted turtle's consumption of plants and animals changes seasonally. In early summer, 60% of its diet comprises insects. In late summer, 55% includes plants.[78] Of note, the western painted turtle also eats many white water-lily seeds. Because the hard-coated seeds remain viable after passing through the turtle, they are dispersed by it.[78]

Predators

Painted turtles are most vulnerable to predators when young.[62] Nests are frequently ransacked and the eggs eaten by garter snakes, crows, chipmunks, thirteen-lined ground and gray squirrels, skunks, groundhogs, raccoons, badgers, gray and red fox, and humans.[62] The small and sometimes bite-size, numerous hatchlings fall prey to water bugs, bass, catfish, bullfrogs, snapping turtles, three types of snakes (copperheads, racers and water snakes), herons, rice rats, weasels, muskrats, minks, and raccoons. As adults, the turtles' armored shells protect the them from many potential predators, but they still fall occasional prey to alligators, ospreys, crows, red-shouldered hawks, bald eagles, and especially raccoons.[62]

Painted turtles defend themselves by kicking, scratching, biting, or urinating.[62] In contrast to land tortoises, painted turtles can right themselves if they are flipped upside down.[79]

Behavior

Daily routine and basking

A cold-blooded reptile, the painted turtle regulates its temperature through its environment, notably by basking. All ages bask for warmth, often alongside other species of turtle. Sometimes more than 50 individuals are seen on one log together.[80] Turtles bask on a variety of objects, often logs, but have even been seen basking on top of common loons that were covering eggs.[81]

The turtle starts its day at sunrise, emerging from the water to bask for several hours. Warmed for activity, it returns to the water to forage.[82] After becoming chilled, the turtle re-emerges for one to two more cycles of basking and feeding.[83] At night, the turtle drops to the bottom of its water body or perches on an underwater object and sleeps.[82]

To be active, the turtle must maintain an internal body temperature between 17–23 °C (63–73 °F). When fighting infection, it manipulates its temperature up to 5 °C (8 °F) higher than normal.[80]

Seasonal routine and hibernation

In the spring, when the water reaches 15–18 °C (59–64 °F), the turtle begins actively foraging. However, if the water temperature exceeds Template:J, the turtle will not feed. In fall, the turtle stops foraging when temperatures drop below the spring set-point.[73]

During the winter, the turtle hibernates. In the north, the inactive season may be as long as from October to March, while the southernmost populations may not hibernate at all.[60] While hibernating, the body temperature of the painted turtle averages Template:J.[84] Periods of warm weather bring the turtle out of hibernation, and even in the north, individuals have been seen basking in February.[85]

The painted turtle hibernates by burying itself, either on the bottom of a body of water, near water in the shore-bank or the burrow of a muskrat, or in woods or pastures. When hibernating underwater, the turtle prefers shallow depths, no more than Template:J. Within the mud, it may dig down an additional Template:J.[84] In this state, the turtle does not breathe, although if surroundings allow, it may get some oxygen through its skin.[86] The species is one of the best-studied vertebrates able to survive long periods without oxygen. Adaptations of its blood chemistry, brain, heart, and particularly its shell allow the turtle to survive extreme lactic acid buildup while oxygen-deprived.[87]

Movement

Searching for water, food, or mates, the painted turtles travel up to several kilometers at a time.[88] During summer, in response to heat and water-clogging vegetation, the turtles may vacate shallow marshes for more permanent waters.[88] Short overland migrations may involve hundreds of turtles together.[60] If heat and drought are prolonged, the turtles will bury themselves and, in extreme cases, die.[89]

Foraging turtles frequently cross lakes or travel linearly down creeks. Daily crossings of large ponds have been observed.[89] Tag and release studies show that sex also drives turtle movement. Males travel the most, up to 26 km (16 mi), between captures; females the second most, up to 8 km (5 mi), between captures; and juveniles the least, less than 2 km (1.2 mi), between captures.[88] Males move the most and are most likely to change wetlands because they seek mates.[89]

The painted turtles, through visual recognition, have homing capabilities.[88] Many individuals can return to their collection points after being released elsewhere, trips that may require them to traverse land. One experiment placed 98 turtles varying several-kilometer distances from their home wetland; 41 returned. When living in a single large body of water, the painted turtles can home from up to 6 km (4 mi) away. Females may use homing to help locate suitable nesting sites.[88]

Life cycle

Mating

The painted turtles mate in spring and fall in waters of 10–25 °C (50–77 °F).Cite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). Males start producing sperm in early spring, when they can bask to an internal temperature of 17 °C (63 °F).[90][91] Females begin their reproductive cycles in mid-summer, and ovulate the following spring.[72]

Courtship begins when a male follows a female until he meets her face-to-face.[71] He then strokes her face and neck with his elongated front claws, a gesture returned by a receptive female. The pair repeat the process several times, with the male retreating from and then returning to the female until she swims to the bottom, where they copulate.[72][71] As the male is smaller than the female, he is not dominant.[71] The female stores sperm, to be used for up to three clutches, in her oviducts; the sperm may remain viable for up to three years.[92] A single clutch may have multiple fathers.[92]

Egg-laying

Nesting is done, by the females only, between late May and mid-July.[72] The nests are vase-shaped and are usually dug in sandy soil, often at sites with southern exposures.[93] Nests are often within 200 m (220 yd) of water, but may be as far away as 600 m (660 yd), with older females tending to nest further inland. Nest sizes vary depending on female sizes and locations but are about 5–11 cm (2–4 in) deep.[93] Females may return to the same sites several consecutive years, but if several females make their nests close together, the eggs become more vulnerable to predators.[93]

The female's optimal body temperature while digging her nest is 29–30 °C (84–86 °F).[93] If the weather is unsuitable, for instance a too hot night in the Southeast, she delays the process until later at night.[93] Painted turtles in Virginia have been observed waiting three weeks to nest because of a hot drought.[94]

While preparing to dig her nest, the female sometimes exhibits a mysterious preliminary behavior. She presses her throat against the ground of different potential sites, perhaps sensing moisture, warmth, texture, or smell, although her exact motivation is unknown. She may further temporize by excavating several false nests[93] as the wood turtles also do.[95]

The female relies on her hind feet for digging. She may accumulate so much sand and mud on her feet that her mobility is reduced, making her vulnerable to predators. To lighten her labors, she lubricates the area with her bladder water.[93] Once the nest is complete, the female deposits into the hole. The freshly laid eggs are white, elliptical, porous, and flexible.[96] From start to finish, the female's work may take four hours. Sometimes she remains on land overnight afterwards, before returning to her home water.[93]

Females can lay five clutches per year, but two is a normal average after including the 30–50% of a population's females that do not produce any clutches in a given year.[93] In some northern populations, no females lay more than one clutch per year.[93] Bigger females tend to lay bigger eggs and more eggs per clutch.[97] Clutch sizes of the subspecies vary, although the differences may reflect different environments, rather than different genetics. The two more northerly subspecies, western and midland, are larger and have more eggs per clutch—11.9 and 7.6, respectively—than the two more southerly subspecies, southern (4.2) and eastern (4.9). Within subspecies, also, the more northerly females lay larger clutches.[93]

Growth

Incubation lasts 72–80 days in the wild,[72] and for a similar period in artificial conditions.[94] In August and September, the young turtle breaks out from its egg, using a special projection of its jaw called the egg tooth.[45] Not all offspring leave the nest immediately, though.[72] Hatchlings north of a line from Nebraska to northern Illinois to New Jersey[98] typically arrange themselves symmetrically[99] in the nest and overwinter to emerge the following spring.[72]

The hatchling's ability to survive winter in the nest has allowed the painted turtle to extend its range further north than any other American turtle. The painted turtle is genetically adapted to survive extended periods of subfreezing temperatures with blood that can remain supercooled and skin that resists penetration from ice crystals in the surrounding ground.[98] The hardest freezes nevertheless kill many hatchlings.[72]

Immediately after hatching, turtles are dependent on egg yolk material for sustenance.[99] About a week to a week and a half after emerging from their eggs (or the following spring if emergence is delayed), hatchlings begin feeding to support growth. The young turtles grow rapidly at first, sometimes doubling their size in the first year. Growth slows sharply at sexual maturity and may stop completely.[100] Likely owing to differences of habitat and food by water body, growth rates often differ from population to population in the same area. Among the subspecies, the western painted turtles are the fastest growers.[101]

Females grow faster than males overall, and must be larger to mature sexually.[100] In most populations males reach sexual maturity at 2–4 years old, and females at 6–10.[91] Size and age at maturity increase with latitude;[37] at the northern edge of their range, males reach sexual maturity at 7–9 years of age and females at 11–16.[71]

Conservation

The decline in painted turtle populations is not a simple matter of dramatic range reduction, like that of the American bison. Instead the turtle is classified as G5 (demonstrably widespread) in its Natural Heritage Global Rank,[102] and the IUCN rates it as a "Least Concern" species.[2] The painted turtle's high reproduction rate and its ability to survive in polluted wetlands and artificially made ponds have allowed it to maintain its range,[26][103] but the post-Columbus settlement of North America has reduced its numbers.[76][104]

"Given the extreme reduction of wetland habitats in the range of the painted turtle in Oregon, there is no question that painted turtle populations have been reduced since pre-European settlement ... it makes more sense to develop conservation plans now rather than requiring evidence of declining and threatened populations ..."

U.S.D.A. Forestry Service report[105]

Only within the Pacific Northwest is the turtle's range eroding. Even there, in Washington, the painted turtle is designated S5 (demonstrably widespread). However, in Oregon, the painted turtle is designated S2 (imperiled),[106] and in British Columbia, the turtle's populations in both the Coast and Interior regions are labeled "endangered"[107] and of "special concern".[108][nb 6]

Much is written about the different factors that threaten the painted turtle, but they are unquantified, with only inferences of relative importance.[62][64][76] A primary threat category is habitat loss in various forms. Related to water habitat, there is drying of wetlands, clearing of aquatic logs or rocks (basking sites), and clearing of shoreline vegetation, which allows more predator access[113] or increased human foot traffic.[114][115] Related to nesting habitat, urbanization or planting can remove needed sunny soils.[116]

Another significant human impact is roadkill—dead turtles, especially females, are commonly seen on summer roads.[117] In addition to direct killing, roads genetically isolate some populations.[117] Localities have tried to limit roadkill by constructing underpasses,[118] highway barriers,[79] and crossing signs.[119] Oregon has introduced public education on turtle awareness, safe swerving, and safely assisting turtles across the road.[120]

In the West, human-introduced bass, bullfrogs, and especially snapping turtles, have increased the predation of hatchlings.[79][121] Outside the Southeast, where sliders are native, released pet red-eared slider turtles increasingly compete with painted turtles.[122] In cities, increased urban predators (raccoons, canines, and felines) may impact painted turtles by eating their eggs.[113]

Other factors of concern for the painted turtles include over-collection from the wild,[123] released pets introducing diseases[124] or reducing genetic variability,[122] pollution,[125] boating traffic, angler's hooks (the turtles are noteworthy bait-thieves), wanton shooting, and crushing by agricultural machines or golf course lawnmowers or all-terrain vehicles.[126][127][128] Gervais and colleagues note that research itself impacts the populations and that much funded turtle trapping work has not been published. They advocate discriminating more on what studies are done, thereby putting fewer turtles into scientists' traps.[129] Global warming represents an uncharacterized future threat.[104][130]

Use

Pets

"... we do not necessarily encourage people to collect these turtles. Turtles kept as pets usually soon become ill ... The best way to enjoy our native turtles is to observe them in the wild ... it would be better to take a picture than a 'picta'!"

Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission[50]

According to a trade data study, painted turtles were the second most popular pet turtles after red-eared sliders in the early 1990s.[131] As of 2010, most US states allow, but discourage, painted turtle pets, although Oregon forbids keeping them as pets,[132] and Indiana prohibits their sale.[124] US federal law prohibits sale or transport of any turtle less than 10 cm (4 in), to limit human contact to salmonella.[133] However, a loophole for scientific samples allows some small turtles to be sold, and illegal trafficking also occurs.[121][134]

Painted turtle pet-keeping requirements are similar to those of the red-eared slider. Keepers are urged to provide them with adequate space and a basking site, and water that is regularly filtered and changed. The animals are described as being somewhat unsuitable for children as they do not enjoy being held. Hobbyists have kept turtles alive for decades.[135][136]

Other uses

The painted turtle is sometimes eaten but is not highly regarded as food,[76][137][138] as even the largest subspecies, the western painted turtle, is inconveniently small and larger turtles are available.[139] Schools frequently dissect painted turtles, which are sold by biological supply companies;[140] specimens often come from the wild but may be captive-bred.[141] In the Midwest, turtle racing is popular at summer fairs.[140][142][143]

Capture

Commercial harvesting of painted turtles in the wild is controversial, and increasingly restricted.[144][145] For instance, Wisconsin formerly had virtually unrestricted trapping of painted turtles, but based on qualitative observations forbade all commercial harvesting in 1997.[146] During the 1990s more than 300,000 painted turtles were collected in Minnesota.[117] Worried by Wisconsin's experience, the state commissioned Gamble and Simon to undertake a quantitative study of the impact of harvesting on their own painted turtles.[140] The scientists found that harvested lakes averaged half the painted turtle density of off-limit lakes. Population modeling demonstrated that unrestricted harvests could produce a large decline in turtle populations.[123] Minnesota forbade new harvesters in 2002, and limited trap numbers. Although harvesting continued,[123] subsequent takes averaged half those of the 1990s.[147] As of 2009, painted turtles faced virtually unlimited harvesting in Arkansas, Iowa, Missouri, Ohio, and Oklahoma.[148] Missouri has prohibited their harvesting.[149]

Individuals who trap painted turtles typically do so to earn additional income,[123][144] selling a few thousand a year at $1–2 each.[140] Many trappers have been involved in the trade for generations, and value it as a family activity.[146] Some harvesters disagree with limiting the catch, saying the populations are not dropping.[146]

Many US state fish and game departments allow non-commercial taking of painted turtles under a creel limit, and require a fishing (sometimes hunting) license;[nb 7] others completely forbid the recreational capture of painted turtles. Trapping is not allowed in Oregon, where western painted turtle populations are in decline,[154] and in Missouri, where there are populations of both southern and western subspecies.[149] In Canada, Ontario protects both subspecies present, the midland and western,[155] and British Columbia protects its dwindling western painted turtles.[45]

Capture methods are also regulated by locality. Typically trappers use either floating "basking traps" or partially submerged, baited "hoop traps".[156] Trapper opinions,[156] commercial records,[147] and scientific studies[156][157][158] show that basking traps are more effective for collecting painted turtles, while the hoop traps work better for collecting "meat turtles" (snapping turtles and soft-shell turtles). Nets, hand capture, and fishing with set lines are generally legal, but shooting (either deliberate or wanton), chemicals, and explosives are forbidden.[nb 8]

Culture

Native American tribes were familiar with the painted turtle—young braves were trained to recognize its splashing into water as an alarm—and incorporated it in folklore.[159] A Potawatomi myth describes how the talking turtles, "Painted Turtle" and allies "Snapping Turtle" and "Box Turtle", outwit the village squaws. Painted Turtle is the star of the conflict and uses his distinctive markings to trick a woman into holding him so he can bite her.[160] An Illini myth recounts how Painted Turtle put his paint on to entice a chief's daughter into the water.[161] In more recent fiction a painted turtle stars in the children's book, Turtle Crossing, in which it grows up and survives close calls with cars.[162]

Public awareness of the wide-ranging painted turtle is additionally reflected by its designation as official reptile in four US states: Colorado (western subspecies,[163] Illinois,[164] Michigan,[165] and Vermont.[166] Private entities also use the painted turtle as a symbol. Wayne State University Press operates an imprint "named after the Michigan state reptile" that "publishes books on regional topics of cultural and historical interest".[167] In California, there is a camp for ill children founded by Paul Newman. Painted Turtle Winery of British Columbia trades on the "laid back and casual lifestyle" of the turtle with a "job description to bask in the sun".[168] Also, there are two Internet companies in Michigan,[169][170] a guesthouse in British Columbia,[171] and a café in Maine.[172]

References

- Notes

- ^ In December 2010 the turtle taxonomy working group provisionally elevated Chrysemys picta dorsalis to the species Chrysemys dorsalis but kept the classification as a subspecies as valid.[2]

- ^ Bishop and Schmidt alluded to glacial origins even earlier.[20]

- ^ All turtle lengths in this article refer to the top shell (carapace) length, not the extended head to tail length.

- ^ Vancouver painted turtle populations may have resulted from escaped pets.[45]

- ^ See the following sources.[38][46][47][48]

- ^ The iconic painted turtle is popular in British Columbia, and the province is spending to save the painted turtle as only a few thousand turtles remain in the entire province.[109][110][111][112]

- ^ State fish and game creel limits.[53][127][128][150][151][152][153]

- ^ State fish and game taking restrictions.[53][127][128][151][152][153]

- Citations

- ^ a b Ernst 2009, pp. 184–185

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rhodin 2010, p. 000.99

- ^ a b Mann 2007, p. 6 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMann2007 (help)

- ^ a b c Ercelawn, Aliya. "Taxonomic information". Herpetology Species Page. Prof. Theodora Pinou (Western Connecticut State University Biological and Environmental Sciences Department). Retrieved 2010-09-18. Cite error: The named reference "WCSU" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Rhodin 2010, pp. 000.91, 000.99

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 214 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b Schneider, Johann Gotttlob (1783). Allgemeine naturgeschichte der schildkröten (Gothic script) (in German). Leipzig. p. 348.

...unter dem namen Testudo picta...

- ^ Fritz 2007, p. 176 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFritz2007 (help)

- ^ Trustees, printed by order of (1844). Catalogue of the Tortoises, Crocodiles, and Amphisbænians, in the Collection of the British Museum. London: Edward Newman. p. 27.

- ^ a b c d Fritz 2007, p. 177 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFritz2007 (help)

- ^ Gray, John Edward (1831). "A synopsis of the species of the class reptilia". In Griffith, Edward (ed.). The Animal Kingdom Arranged in Conformity with Its Organization: The class reptilia, with specific descriptions, volume 9. London: Whittikar, Treacher. p. 12.

- ^ Fritz 2007, p. 178 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFritz2007 (help)

- ^ Agassiz, Louis (1857). Contributions to the natural history of the United States of America: First monograph: in three parts. Boston: Little, Brown. pp. 439–440.

- ^ "Taxonomy chapter for turtle, eastern painted (030060)". BOVA Booklet. Virginia Fish and Wildlife Information Service. 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- ^ Beltz, Ellin (2006). "Scientific and common names of the reptiles and amphibians of North America – explained". Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ^ Hoffman, Richard L. (1987-03). "'Skilpot': a request for information" (PDF). Virginia Herpetological Society Bulletin. 85.

When I was a child living in Clifton Forge, VA, the name by which I learned Chrysemys picta, painted turtle, was 'skilpot'.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Dobie, James L. (1981–1982). "The taxonomic relationship between Malaclemys Gray, 1844 and Graptemys agassiz, 1857 (Testudines: Emydidae)". Tulane Studies in Zoology and Botany. 23: 85–103. Retrieved 2011-01-04.

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 213 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Holman, J. Alan (1977-09). "Comments on turtles of the genus Chrysemys Gray". Herpetologica. 33 (3): 274.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) (subscription required) - ^ a b Bishop, Sherman; Schmidt, F. J. W. (1931). turtles "The painted turtles of the genus Chrysemys". Zoological Series. 18 (4). Field Museum of Natural History: 123–139. Retrieved 2011-01-06.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b Bleakney, Sherman (1958-07-23). "Postglacial dispersal of the turtle Chrysemys picta". Herpetologica. 14 (2): 101–104. Retrieved 2011-01-08. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e Ernst 2009, p. 185

- ^ a b c Ernst 2009, p. 187

- ^ Starkey, David (2003). "Molecular systematics, phylogeography, and the effects of pleistocene glaciation in the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) complex" (PDF). Evolution. 57 (1): 119–128.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mann 2007, p. 2 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMann2007 (help)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ercelawn, Aliya. "Species identification". Herpetology Species Page. Prof. Theodora Pinou (Western Connecticut State University Biology and Environmental Sciences). Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ a b "Painted turtle (Chrysemys picta)". Savannah River Ecology Laboratory Herpetology Program. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ a b c d e Ernst 1994, p. 276

- ^ a b c Ernst 2009, p. 184

- ^ Cohen, Mary (1992-10). "The painted turtle, Chrysemys picta". Tortuga Gazette. 28 (10): 1–3. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ernst 1994, p. 277

- ^ Ernst 2009, p. 263

- ^ "Reptiles: Turtle & tortoise". Animal Bytes. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

Turtle— Spends most of its life in the water. Turtles tend to have webbed feet for swimming.

- ^ "Painted turtle". US Bureau of Land Management. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

They have webbed toes for swimming...

- ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 291

- ^ Ernst 1972, p. 143

- ^ a b Ernst 2009, p. 197

- ^ a b Lee-Sasser, Marisa (2007-12). "Painted turtle in Alabama". Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved 2010-08-12.

Intergrades exhibit a mix of characteristics where their ranges overlap.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Senneke, Darrell (2003). "Differentiating painted turtles (Chrysemys picta ssp)". World Chelonian Trust. Retrieved 2010-12-09.

- ^ "Eastern painted turtle Chrysemys picta picta (Schneider)". Nova Scotia Museum. 2007. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ "Midland painted turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata)". Natural Resources Canada. 2007-09-24. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ a b Carr 1952, p. 226 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b c Ernst 2009, p. 186

- ^ a b Carr 1952, p. 221 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b c d e Blood, Donald A. (1998-03). "Painted turtle" (brochure). Wildlife Branch, Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, British Columbia.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wright, Katherine M. (2002). "Painted turtles (Chrysemys picta) of Vermont: An examination of phenotypic variation and intergradation". Northeastern Naturalist. 9 (4). Humboldt Field Research Institute: 363–380. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Weller, Wayne F. (2010). "Quantitative assessment of intergradation between two subspecies of painted turtles, Chrysemys picta bellii and C. p. marginata, in the Algoma district of west central Ontario, Canada" (PDF). Herpetological Conservation and Biology. 5 (2): 166–173.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mann 2007, p. 20 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMann2007 (help)

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 215 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b Shiels, Andrew L. "A picta worth a thousand words: Portrait of a painted turtle" (PDF). Pennsylvania Angler and Boater catalog. Pennsylvania Fish and Boating Commission. pp. 28–30.

- ^ a b Dixon, James Ray (2000). "painted+turtle"#v=onepage Amphibians and reptiles of Texas. Texas A&M University Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0890969205. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- ^ "Species of turtles in OK". Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- ^ a b c "Nongame species protected by Alabama regulations". Alabama Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ^ a b "Arizona game and fish department" (PDF). Unpublished abstract compiled and edited by the Heritage Data Management System, Arizona Game and Fish Department, Phoenix, AZ. 2007-02-22.

- ^ a b Degenhardt, William G. (1996). Amphibians and reptiles of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-8263-1695-6. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

...extreme Northern Chihuahua, Mexico.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Smith, Hobart M.; Taylor, Edward H. (1950). An annotated checklist and key to the reptiles of Mexico exclusive of the snakes. Vol. 199. Smithsonian Institute. pp. 33–34. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

Recorded only from the state of Chihuahua: Rio Santa Maria, near Progreso

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Tanner, Wilmer W. (1987-07). "Lizards and turtles of western Chihuahua" (linked pdf). Great Basin Naturalist. 47 (3): 383–421. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

Rio Santa Maria, above bridge west of Galeana...

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Stebbins, Robert C.; Peterson, Roger Tory (2003). A field guide to western reptiles and amphibians (Peterson field guide). New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 251–252. ISBN 978-0395982723. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ^ Spinks, Phillip Q. (2003). "Survival of the western pond turtle (Emys marmorata) in an urban California environment" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 113: 257–267.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Carr 1952, p. 217 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 231 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b c d e f Ernst 1994, p. 294

- ^ a b c Ernst 1994, p. 295

- ^ a b c Ernst 2009, p. 211

- ^ Gibbons, J. Whitfield (1987-05). "Why do turtles live so long" (PDF). BioScience. 37 (4): 262–269.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Zweifel, Richard George (1989). Long-term ecological studies on a population of painted turtles, Chrysemys picta, on Long Island, New York (American Museum novitates no. 2952) (PDF). New York: American Museum of Natural History. pp. 18–20.

- ^ Fowle, Suzanne C. (1996). "Effects of roadkill mortality on the western painted turtle (Chrysemys picta belli) in the Mission valley, western Montana". In Evink, G.; Zeigler, D.; Garrett, P.; Berry, J (ed.). Highways and movement of wildlife: improving habitat connections and wildlife passageways across highway corridors. Proceedings of the transportation-related wildlife mortality seminar of the Florida Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration. Report FHWA-PD-96-041 (PDF). Florida Department of Transportation (Orlando). pp. 205–223.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Cagle, Fred R. (1939-09-09). "A system of marking turtles for future identification". Copeia. 3: 170–173.

A system to be used in marking turtles must be permanent, since turtles have a long life span, must definitely identify each individual, must not handicap the turtle in any way, and should be simple and easy to use.

(subscription required) - ^ Congdon, Justin D. (2003). "Testing hypotheses of aging in long-lived painted turtles (Chrysemys picta)" (PDF). Experimental Gerontology. 38: 765–772.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ernst 1994, pp. 294–295

- ^ a b c d e "Painted turtle research in Algonquin provincial park". The Friends of Algonquin Park. 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2010-09-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ercelawn, Aliya. "Reproduction". Herpetology Species Page. Prof. Theodora Pinou (Western Connecticut State University Biology and Environmental Sciences). Retrieved 2010-09-18. Cite error: The named reference "wcsu.edu reproduction" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d Ernst 2009, p. 293

- ^ a b Carr 1952, p. 218 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Carr 1952, pp. 232–233 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b c d Carr 1952, p. 228 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Carr 1952, pp. 227–228 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b Carr 1952, p. 223 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b c Chaney, Rob (2010-07-01). "Painted native: Turtles indigenous to western Montana have vivid designs, secrets". Missoulian. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 283

- ^ Gervais 2009, p. 13 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 282

- ^ Ernst 1994, pp. 282–283

- ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 284

- ^ Ernst 1994, p. 281

- ^ Jackson, D. C. (2004-08). "Avenues of extrapulmonary oxygen uptake in western painted turtles (Chrysemys picta belli) at 10 °C". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part A, Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 139 (2): 221–227. doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2004.09.005. PMID 15528171.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jackson, Donald C. (2002). "Hibernating without oxygen: physiological adaptations of the painted turtle". The Journal of Physiology. 543 (3): 731–737. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ^ a b c d e Ernst 1994, p. 286

- ^ a b c Ernst 2009, p. 195

- ^ Ernst 1994, p. 289

- ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 287

- ^ a b Ernst 2009, p. 200

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ernst 2009, p. 201

- ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 290

- ^ Ernst 2009, p. 259

- ^ Ernst 2009, p. 203

- ^ Ernst 2009, p. 202

- ^ a b Packard 2002, p. 300 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFPackard2002 (help)

- ^ a b Ernst 2009, p. 206

- ^ a b Ernst 1994, p. 292

- ^ Ernst 2009, p. 207

- ^ Gervais 2009, p. 5 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ "Painted turtle: Chrysemys picta". Turtle Conservation Project. Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- ^ a b Ernst 2009, pp. 23–32

- ^ Gervais 2009, pp. 31–32 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ Gervais 2009, p. 9 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ "Species profile western painted turtle Pacific coast population". Species at Risk Public Registry. Government of Canada. 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

- ^ "Species profile western painted turtle intermountain – Rocky Mountain population". Species at Risk Public Registry. Government of Canada. 2010-01-11. Retrieved 2010-11-12.

- ^ Carnahan, Todd. "Western painted turtles". Habitat Acquisition Trust. Retrieved 2010-12-11.

- ^ "B.C. frogwatch program: Painted turtle". British Columbia Ministry of Environment. Retrieved 2010-12-11.

- ^ Nilsen, Emily (2010-08-09). "Protecting the painted turtle". Nelson Express. Retrieved 2010-12-11.

- ^ COSEWIC 2006, p. 29

- ^ a b Gervais 2009, p. 33 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ Hayes, M. P. (2002). "The western painted turtle (Chrysemys picta bellii) at the Rivergate industrial district: management options and opportunities".

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) cited in Gervais, Jennifer (2009). "Conservation assessment for the western painted turtle in Oregon: (Chrysemys picta bellii) version 1.1". U.S.D.A. Forest Service. Archived from the original (technical report) on 2010-12-17.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Leuteritz, T. E. (1996). "Preliminary observations on the effects of human perturbation on basking behavior in the midland painted turtle (Chrysemys picta marginata)". Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society. 32: 16–23.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) cited in Gervais, Jennifer (2009). "Conservation assessment for the western painted turtle in Oregon: (Chrysemys picta bellii) version 1.1". U.S.D.A. Forest Service. p. 36. Archived from the original (technical report) on 2010-12-17.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gervais 2009, p. 36 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ a b c Gervais 2009, p. 34 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ Gervais 2009, p. 47 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ Holmes, Dianne. "Report on turtle crossing signs proposal" (PDF). Region of Ottawa-Carleton.

...inexpensive and morally exemplary..."

- ^ Kenagy, Meg (2010-02). "On the ground: The Oregon conservation strategy at work". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW). Retrieved 2011-01-07.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Gervais 2009, p. 35 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ a b Gervais 2009, p. 6 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ a b c d Gamble, Tony (2004). "Comparison of harvested and nonharvested painted turtle populations" (PDF). Wildlife Society Bulletin. 32 (4): 1269–1277.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Turtles as pets". Indiana Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 2010-12-11.

It is illegal in the State of Indiana to sell native species of turtles

- ^ Gervais 2009, pp. 36–37 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ Gervais 2009, p. 37 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ a b c "Arizona reptile and amphibian regulations" (PDF). Arizona Game and Fish Department.

- ^ a b c "Nongame fish, reptile, amphibian and aquatic invertebrate regulations". Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ^ Gervais 2009, p. 40 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ Gervais 2009, p. 38 harvnb error: multiple targets (4×): CITEREFGervais2009 (help)

- ^ Ernst 2009, p. 26

- ^ "Oregon native turtles" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

- ^ "Title 21 CFR 1240.62". U. S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ^ Reinberg, Steven (2010-03-23). "Pet turtles pose salmonella danger to kids: They're banned from sale by law but still appear at flea markets, pet shops, experts say". ABC News. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- ^ Senneke, Darrel (2003). "Chrysemys picta – (Painted turtle) care" (PDF). World Cheledonian Trust.

- ^ Bartlett, R. D.; Bartlett, Patricia (2003). Aquatic turtles: Sliders, cooters, painted, and map turtles. Hong Kong: Barron's Educational Series. pp. 1–48. ISBN 978-0764122781. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- ^ Carr 1952, pp. 218–219 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 233 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ Carr 1952, p. 224 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCarr1952 (help)

- ^ a b c d Gamble, Tony (2003-05-30). "The commercial harvest of painted turtles in Minnesota: final report to the Minnesota department of natural resources, natural heritage and nongame research program" (technical report). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pike, Sue (2010-07-2010). "Painted turtles often used for classroom dissection". Seacoast Media (Dow Jones wire service). Retrieved 2010-12-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Freeman, Eric (2010-06-08). "Rupp, grandson trap turtles to compete in local races". Columbus Telegram. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

- ^ "Fast times in Nisswa: Swift turtles mix with power shoppers in a Minnesota lake-country oasis". Midwest Weekends. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

- ^ a b Keen, Judith (2009-07-20). "States rethink turtle trapping". USA Today. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ Thorbjarnarson, J. (2000). "Human use of turtles". In Klemens, M. W (ed.). Turtle conservation. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 33–84.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) cited in Gamble, Tony (2004). "Comparison of harvested and nonharvested painted turtle populations" (PDF). Wildlife Society Bulletin. 32 (4): 1269–1277.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Arnie, Jennifer. "The turtle trap". Imprint Magazine. The University of Minnesota Bell Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ a b "Minnesota commercial turtle harvest: 2005" (report). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources.

- ^ "Southern and midwestern turtle species affected by commercial harvest" (PDF). Center for Biological Diversity.

- ^ a b "MDC discover nature turtles". Missouri Department of Conservation. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

Missouri has 17 kinds of turtles; all but three are protected ... common snapping turtles and two softshells ...

- ^ "Resident license information and applications packets". Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ^ a b "Regulations on the take of reptiles and amphibians" (PDF). Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

- ^ a b "Summary of Pennsylvania fishing laws and regulations – reptiles and amphibians – seasons and limits". Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ^ a b "Rules and regulations for reptiles and amphibians in New Hampshire". New Hampshire Fish and Game Department. Retrieved 2010-12-08.

- ^ "Holding, propagating, protected wildlife" (PDF). Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

- ^ "Hunting regulations 2010–2011" (PDF). Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

- ^ a b c Gamble, Tony (2006). "The relative efficiency of basking and hoop traps for painted turtles (Chrysemys picta)" (PDF). Herpetological Review. 37 (3): 308–312.

- ^ Browne, C. L. (2005). "Capture success of northern map turtles (Graptemys geographica) and other turtle species in basking vs. baited traps". Herpetological Review. 36: 145–147.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) cited in Gamble, Tony (2006). "The relative efficiency of basking and hoop traps for painted turtles (Chrysemys picta)" (PDF). Herpetological Review. 37 (3): 308–312. - ^ McKenna, K. C. (2001). "Chrysemys picta (painted turtle). Trapping". Herpetological Review. 32: 184. cited in Gamble, Tony (2006). "The relative efficiency of basking and hoop traps for painted turtles (Chrysemys picta)" (PDF). Herpetological Review. 37 (3): 308–312.

- ^ Macfarlan, Allan; Macfarlan, Paulette (1985-03-01). Handbook of American Indian games. Dover Publications. p. 62. ISBN 978-0486248370.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Potawatomi oral tradition". Milwaukee Public Museum. Retrieved 2010-12-17. Adapted from Skinner, Alanson (1927). "Mythology and Folklore". The Mascoutens or Prairie Potawatomi Indians, Volume 6. Vol. 3. Indiana University: Board of Trustees.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Illinois State Museum. The painted turtle. Retrieved 2010-12-10. "As told by an unidentified Peoria informant to Truman Michelson, 1916; after Knoepfle 1993."

- ^ Chrustowski, Rick (2006). Turtle Crossing. Henry Hold & Co. ISBN 978-0805074987.

So the next time you see a TURTLE CROSSING sign, keep your eyes open—if you're lucky, you just might see a painted turtle on her way to make a nest.

- ^ "Colorado state archives symbols & emblems". colorado.gov. State of Colorado. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- ^ "State symbols". Illinois.gov. Retrieved 2010-12-15.

- ^ "Michigan's state symbols" (PDF). Michigan History magazine. 100. 2002-05.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Joint resolution relating to the designation of the painted turtle as the state reptile". Retrieved 2010-12-15.

- ^ "Painted turtle publishing imprint website". Wayne State University Press. Retrieved 2010-12-07.

- ^ "Painted turtle winery". Retrieved 2010-12-07.

- ^ "Painted turtle web hosting". Painted Turtle Web Hosting. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- ^ "Painted turtle web design". Painted Turtle Web Design. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- ^ "Painted turtle guesthouse website". Retrieved 2010-12-06.

- ^ Staff reports (2010-03-12). "Eat & run". The Portland Press Herald. Retrieved 2010-12-07.

- Bibliography

- "COSEWIC assessment and status report on the western painted turtle Chrysemys picta bellii" (PDF). Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 2006. p. 29.

- Carr, Archie (1952). "Genus Chrysemys: The Painted Turtles". Handbook of Turtles: The Turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California. Binghamton, New York: Comstock Publishing Associates a Division of Cornell University Press. pp. 213–234.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|work=ignored (help) - Ernst, Carl H.; Barbour, Roger William (1972). "Chrysemys picta". Turtles of the United States. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 138–146. ISBN 0-8131-1272-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Ernst, Carl H.; Barbour, Roger William (1989). "Chrysemys". Turtles of the World. Washington, D.C., and London: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 201–203. ISBN 0-87474-414-8.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Ernst, Carl H.; Barbour, Roger William; Lovich, Jeffery E. (1994). Turtles of the United States and Canada. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 276–296. ISBN 1-56098-346-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Ernst, Carl H.; Lovich, Jeffery E. (2009). Turtles of the United States and Canada (2 ed.). JHU Press. pp. 185–259. ISBN 9780801891212.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Fritz, Uwe (2007). "Checklist of chelonians of the world". Verterbrate zoology. 57 (2): 149–368. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-17.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Gervais, Jennifer (2009). "Conservation assessment for the western painted turtle in Oregon: (Chrysemys picta bellii) version 1.1". U.S.D.A. Forest Service. pp. 4–61. Archived from the original (technical report) on 2010-12-17.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Mann, Melissa (May 2007). A taxonomic study of the morphological variation and intergradation of Chrysemys picta (Schneider) (Emydidae, Testudines) in West Virginia (PDF). (Thesis) Marshall University. pp. i-64.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Packard, Gary, C. (2002). "Cold-tolerance of hatchling painted turtles (Chrysemys picta bellii) from the southern limit of distribution" (PDF). Journal of Herpetology. 36 (2): 300–304.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rhodin, Anders G.J.; van Dijk, Peter Paul; Inverson, John B.; Shaffer, H. Bradley (2010-12-14). "Turtles of the world, 2010 update: Annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution and conservation status". Chelonian Research Monographs. 5: 000.89–000.138. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-15.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Missouri Department of Conservation video of southern painted turtle (click video link): Note the discussion of red line on top of shell.

- Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife video of western painted turtle. See from 0:20 to 1:20 how to differentiate the western painted turtle from the red-eared slider.

Media related to painted turtle at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to painted turtle at Wikimedia Commons