Circassians

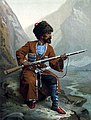

Flag of the Republic of Adygea  Adyghe people from the mountains of the Caucasus in traditional costumes | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 2,000 000[1] | |

| 709,003[1] | |

| 100,000 (1987)[2] | |

| 65,000[3] | |

| 40,000[3] | |

| 9,000[1] | |

| 8,000 (1988)[4] | |

| 4,000[3] | |

| 500[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Adyghe and speak the language of the country of birth (e.g. Russian, Turkish, Arabic, etc.) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Abkhazians (Abaza, Abazin) and Ubykh | |

The Adyghe or Adygs (Adyghe: Адыгэ,Arabic: شركس/جركس), also often known as Circassians [5], are a North Caucasian and European nation and an ethnic group who belong to one of the oldest indigenous peoples of the Caucasus and are among the original inhabitants of the Caucasus.[6][7][8]

Adyghe people mostly speak Adyghe and most practice Sunni Islam. Turkey is home to the largest Adyghe community in the world, containing about half the world's Adygs.

Etymology

The Adyghe people call and distinguish themselves from other peoples of the Caucasus by the name Attéghéi or Adyghe, which is really the native name of the Circassians[citation needed]. “Atté” in the Circassian language means "height" of a place to signify a mountaineer or a highlander, and “ghéi” means the sea, signifying a people dwelling and inhabiting a mountainous country, a region near the sea coast, or between two seas. They possessed ancient cultures for thousands of years such as the Dolmens of North Caucasus, and they were famous in their Nart sagas.[9][10][11]

While Adyghe is the name this people apply to themselves, in the West they are often known as Circassians, a term which occasionally applied to a broader group of peoples in the North Caucasus. The name Circassian is purely of Italian origin and came from the medieval Genoese merchants and travelers who first gave currency to the name.[12][13][14] The name Cherkess is not a native name, but one applied to the Adyghe by the Turkic peoples (principally Kyrgyz,[12] Tatar[15][16][17][18] and Turkish[19]) and the Russians. The name Cherkess was usually explained to mean Warrior Cutter due to how fast they were able to cut down Russian and Turkish forces,[20] but is derived from the circumstance of the Circassians never permitting the march of a foreign invader, or foreign soldier through their lands and is considered by some and is applied indirectly to the strenuous defense against invaders.[21] By others, the name is supposed to refer to the predatory habits among Adyghe tribes and Abazin. The Russians gave the collective name of Cherkess to all the mountaineers of Circassia who are divided into many tribes.[22]

Genetics

In the recent study: "Worldwide Human Relationships Inferred from Genome-Wide Patterns of Variation (2008)", geneticists using more than 650,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) samples from the Human Genome Diversity Panel, found that the Adygei (Adyghe) population had shared ancestry with European, Central and South Asian populations.[23]

History

Origins

The Adyghe first emerged as a coherent entity somewhere around the 10th century[citation needed], although references to them exist much earlier.[citation needed]

They were never politically united, a fact which reduced their influence in the area and their ability to withstand periodic invasions from groups like the Mongols, Avars, Pechenegs, Huns, and Khazars.

Russian conquest of the Caucasus and the exile of the Adygs

The Adyghe people converted to Christianity prior to the 5th century. In the 15th century, under the influence of the Tatars of Crimea and Ottoman clerics, the Adygs converted to Islam.

Between the late 18th and early to mid-19th centuries the Adyghe people lost their independence as they were slowly conquered by Russia in a series of wars and campaigns. During this period, the Adyghe plight achieved a certain celebrity status in the West, but pledges of assistance were never fulfilled. After the Crimean War, Russia turned her attention to the Caucasus in earnest, starting with the peoples of Chechnya and Dagestan. In 1859, the Russians had finished defeating Imam Shamil in the eastern Caucasus, and turned their attention westward. Eventually, the long lasting Russian–Circassian War ended with the defeat of the Adyghe forces, which was finalized with the signing of loyalty oaths by Adyghe leaders on 2 June 1864 (21 May, O.S.).

The Conquest of the Caucasus by the Russian Empire in the 19th century during the Russian-Circassian War, led to the destruction and killing of many Adygs - Towards the end of the conflict, the Russian General Yevdokimov was tasked with driving the remaining Circassian inhabitants out of the region, primarily into the Ottoman Empire. This policy was enforced by mobile columns of Russian riflemen and Cossack cavalry.[24][25][26] "In a series of sweeping military campaigns lasting from 1860 to 1864 . . . the northwest Caucasus and the Black Sea coast were virtually emptied of Muslim villagers. Columns of the displaced were marched either to the Kuban [River] plains or toward the coast for transport to the Ottoman Empire . . . . One after another, entire Circassian tribal groups were dispersed, resettled, or killed en masse"[26] This expulsion, along with the actions of the Russian military in acquiring Circassian land,[27] has given rise to a movement among descendants of the expelled ethnicities for international recognition that genocide was perpetrated.[28] In 1840, Karl Friedrich Neumann estimated the Circassian casualties to be around one and a half million.[29] Some sources state that hundreds of thousands of others died during the exodus.[30] Several historians use the term 'Circassian massacres'[31] for the consequences of Russian actions in the region.[32]

Like other ethnic minorities under Russian rule, the Adygs who remained in the Russian Empire borders were subjected to policies of mass resettlement. Collectivization under the communists also took its toll.

The Ottoman Empire, which ruled most of the area south of Russia considered the Adyghe warriors to be courageous and well-experienced, and as a result encouraged them to settle in various near-border settlements of the Ottoman empire in order to strengthen the empire's borders.

The Adyghes in the Middle East in modern times

The Adyghes who were settled by the Ottomans in various near-border settlements across the empire, ended up living across many different territories in the Middle East who belonged at the time to the Ottoman Empire and which are located nowadays in the following countries:

- Turkey, the country which contains today the largest adyghe population in the world. The Adygs settled in three main regions in Turkey – the region of Trabzon, located along the shores of the Black Sea, the region near the city of Ankara, the region near the city of Kayseri, and in the western part of the country near the region of Istanbul, this specific region experienced a severe earthquake in 1999. Many Adygs played key roles in the Ottoman army and also participated in the Turkish War of Independence.

- Syria. Most of the Adygs who immigrated to Syria settled in the Golan Heights. Prior to the Six Day War, the Adygs people were the majority group in the Golan Heights region - their number at that time is estimated at 30,000. The most prominent settlement in the Golan was the town of Quneitra.

- Jordan. The Adygs had a major role in the history of the Kingdom of Jordan. The Adygs initially established the village of Amman,[33] hence the first four mayors were Circassians.[34]Over the years various Adygs have served in distinguished roles in the kingdom of Jordan. An Adyghe has served before as a prime minister (Sa`id al-Mufti), ministers (commonly at least 1 minister should represent the Circassians in each cabinet), high rank officers, etc, and due to their important role in the history of Jordan it is Adyghe who form the Hashemites Honor guard at the Royal palaces, and they represented Jordan in the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo in 2010 joining other Honor guards such as the The Airborne Ceremonial Unit.[35][36]

- Israel. The Adygs initially settled in three places – in Kfar Kama , in Rehaniya and in the region of Hadera. Due to a Malaria epidemic, the Adyghe settlement near Hadera was eventually abandoned.

Culture

Adyghe society prior to the Russian invasion was highly stratified. While a few tribes in the mountainous regions of Adygeya were fairly egalitarian, most were broken into strict castes. The highest was the caste of the "princes", followed by a caste of lesser nobility, and then commoners, serfs, and slaves. In the decades before Russian rule, two tribes overthrew their traditional rulers and set up democratic processes, but this social experiment was cut short by the end of Adyghe independence.

The main Adyghe tribes are: Abzekh, Adamey, Bzhedugh, Hakuch, Hatukuay, Kabardey, Kemirgoy, Makhosh, Natekuay, Shapsigh (Shapsugh), Yegerikuay, Besleney. Most Adyghe living in Caucasia are Bzhedugh, Kabarday and Kemirgoy, while the majority in diaspora are Abzekh and Shapsigh (Shapsugh). Standard Adyghe language is based on Kemirgoy dialect.

Religion

Before monotheistic religion, the Circassians were polytheistic and adhered to their ancient indigenous beliefs, worshiping multiple deities, or gods and goddesses.[37][38][39][40] Between the 2nd century[41] and the 4th century,[42] Christianity reached and spread throughout the Caucasus and was first introduced between the 4th century[43][44] and the 6th century[45] under Greek Byzantine influence and later through the Georgians between the 10th century and the 13th century. During that period, Circassians began to accept Christianity as their national religion, but did not fully adopt Christianity as elements of their ancient indigenous pagan beliefs still survived.

Islam penetrated the northeastern region of the Caucasus, principally Dagestan, as early as the 7th century, but was first introduced to the Circassians between the 16th century and in the middle of the 19th century under the influence of the Crimean Tatars and the Ottoman Turks. It was only after the Russian conquest of the Caucasus when Circassians as well as other peoples of the Caucasus were forced out of their ancestral homeland and settled in different regions of the Ottoman Empire did they begin to fully accept and adopt Islam as their national religion.

The Naqshbandi tariqa of Sufi Islam was also introduced to the Circassians in the late 18th century under the influence of Sheikh Mansur who was the first to preach the Naqshbandi tariqa in the northeastern region of the Caucasus and later through Imam Shamil in the middle of the 19th century.

Today, the majority of Circassians are predominately Sunni Muslim and adhere to the Hanafi school of thought, or law, the largest and oldest school of Islamic law in jurisprudence within Sunni Islam.

Language

Today most Adyghe speak Russian, English, Turkish, Arabic, French, German, and/or the original Adyghe language.

The majority of the Circassian people speak the Adyghe language, when the Kabarday tribe speaks the Adyghe language in the Kabardian dialect. This language has a number of dialects spoken by the different Circassian tribes and the pronunciation of words is slightly different in each place in the world. The Adyghe language belongs to the family of Northwest Caucasian languages. The Adyghe language is spoken among all the Circassian communities around the world, with circa 125,000 speakers who live in the Russian Federation (part of them live in the Republic of Adygea where the Adyghe language is defined as the official language.) the world's largest Adyghe speaking community is the Circassian community in Turkey - this community has circa 150,000 Adyghe speakers.

Adyghe Xabze

Adyghe Xabze (Adyghe: Адыгэ Хабзэ) is the epitomy of Circassian culture and tradition. It is their code of honour and is based on mutual respect and above all requires responsibility, discipline and self-control. Adyghe Xabze functions as the Circassian unwritten law yet was highly regulated and adhered to in the past. The Code requires that all Circassians are taught courage, reliability and generosity. Greed, desire for possessions, wealth and ostentation are considered disgraceful ("Yemiku") by the Xabze code. In accordance with Xabze, hospitality was and is particularly pronounced among the Circassians. A guest is not only a guest of the host family, but equally a guest of the whole village and clan. Even enemies are regarded as guests if they enter the home and being hospitable to them as one would with any other guest is a sacred duty.

Circassians consider the host to be like a slave to the guest in that the host is expected to tend to the guest's every need and want. A guest must never be permitted to labour in any way, this is considered a major disgrace on the host.

Every Circassian arises when someone enters the room, providing a place for the person entering and allowing the newcomer to speak before everyone else during the conversation. In the presence of elders and women respectful conversation and conduct is essential. Disputes are stopped in the presence of women and domestic disputes are never continued in the presence of guests. A woman can request disputing families to reconcile and they must comply with her request. A key figure in Circassian culture is the person known as the "T'hamade" (Adyghe: (Тхьэмадэ- Тхьэматэ)), who is often an elder but also the person who carries the responsibility for functions like weddings or circumcision parties. This person must always comply with all the rules of Xabze in all areas of his life.

Circassian Xabze is well known amongst their neighboring communities.

Traditional clothing

The Adyghe traditional clothing (Adyghe: Адыгэ Щыгъыныхэр) refers to the historical clothing worn by the Adyghe people. The traditional female clothing (Adyghe: Бзылъфыгъэ Шъуашэр) was very diverse and highly decorated and mainly depends on the region, class of family, occasions, and tribes . The traditional female costume is composed of a dress (Adyghe: Джанэр), coat (Adyghe: Сае), shirt, pant (Adyghe: Джэнэк1акор), vest (Adyghe: К1эк1),lamb leather bra (Adyghe: Шъохътан), a variety of hats (Adyghe: Пэ1охэр) ,shoes, and belts (Adyghe: Бгырыпхыхэр). Holiday dresses are made of expensive fabrics such as silk and velvet. The traditional colors of females clothing rarely includes blue, green or bright-colored tones, instead mostly white, red, black and brown shades wear.

The traditional male costume (Adyghe: Адыгэ хъулъфыгъэ шъуашэр) includes a coat with wide sleeves, shirt, pants, a dagger ,sword, and a variety of hats and shoes. Traditionally, young men in the warriors times wore coat with short sleeves – in order to feel more comfortable in combats. Different colors of clothing for males were strictly used to distinguish between different social classes, for example white is usually worn by princes, red by nobles, gray, brown, and black by peasants (blue, green and the other colors were rarely worn). A compulsory item in the traditional male costume is a dagger and a sword. The traditional Adyghean sword is called Shashka. It is a special kind of sabre; a very sharp, single-edged, single-handed, and guardless sword. Although the sword is used by most of Russian and Ukrainian Cossacks, the typically Adyghean form of the sabre is longer than the Cossack type, and in fact the word Shashka came from the Adyghe word "Sashkhwa" (Adyghe: (Сашьхъуэ)) which means "long knife".

Traditional cuisine

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2010) |

The Adyghe Cuisine is rich with different type dishes,[46] in the summer, the traditional dishes consumed by the Adyghe people were mainly dairy products and vegetable dishes. In the winter and spring it was mainly flour and meat dishes.

The Circassian cheese considered one of the famous type of Cheeses in the North Caucasus and world wide.

A popular traditional dish is chicken or turkey with sauce, seasoned with crushed garlic and red pepper. Mutton and beef are served boiled, usually with a seasoning of sour milk with crushed garlic and salt.

On holidays the Adyghe people traditionally make Haliva (fried triangular pasties with mainly cottage cheese or potato). (from toasted millet or wheat flour in syrup), baked cakes and pies.

Traditional mats

The Adyghes were famous in making mats (Adyghe: П1уаблэхэр) or rugs worldwide for thousands of years, and they were making their mats from the rtaderia selloana (Adyghe: 1ут1эн, Arabic: نبات الحلفا) like other Caucasian nations.

Making mats was very hard work in which collecting raw materials is restricted to a specific period of time within the year. The raw materials were dried, and based on the intended colors, different methods of drying were applied. For example, when dried in the shade, its color changed to a beautiful light gold color. If it were dried in direct sun light then it would have a silver color, and if they wanted to have a dark color for the mats, the raw materials were put in a pool of water and covered by poplar leaves (Adyghe: Ек1эпц1э, Arabic: شجر الحور).

The mats were adorned with images of birds, beloved animals (horses), and plants, and the image of the sun was widely used.

The mats were used for different reasons due to their characteristic resistance to humidity and cold, and in retaining heat. Also, there was a tradition in Circassian homes to have two mats hanging in the guest room, one used to hang over rifles(Adyghe: Шхончымрэ) and pistols (Adyghe: Къэлаеымрэ), and the other used to hang over musical instruments.

The mats were used to pray upon, and it was necessary for every Circassian girl to make three mats before marriage; a big mat, a small mat, and the last for praying as a Prayer rug. These mats would give the grooms an impression as to the success of their brides in their homes after marriage.[47]

The twelve Adyghe tribes

The main Adyghe tribes are:

- Abadzeh (Adyghe: Абдзах)

- Besleney (Adyghe: Бэслэней)

- Bzhedug (Adyghe: Бжъэдыгъу)

- Yegeruqay (Adyghe: Еджэркъуай)

- Zhaney (Adyghe: Жанэ)

- Kabarday (Adyghe: Къэбэртай)

- Mamheg (Adyghe: Мамхыгъ)

- Natuhay (Adyghe: Нэтыхъуай, Нэтыхъуадж)

- Temirgoy (Adyghe: Кlэмгуй)

- Ubyh (Adyghe: Убых)

- Shapsug (Adyghe: Шапсыгъ)

- Hatuqwai (Adyghe: Хьатикъуай)

Many Adyghe allocated in the Caucasus region are Bzhedug and Temirgoy, while the majority of those in the diaspora (see next section) are Abadzeh and Shapsug.

The Adyghe diaspora

Adyghe have lived outside the Caucasus region since the Middle Ages. They were particularly well represented in the Mamluks of Turkey and Egypt. In fact, the Burji dynasty which ruled Egypt from 1382 to 1517 was founded by Adyghe Mamluks.

Much of Adyghe culture was disrupted after their conquest by Russia in 1864. This led to a diaspora of the peoples of the northwest Caucasus, known as Muhajirism, mostly to various parts of the Ottoman Empire.

The largest Adyghe diaspora community today is in Turkey, especially in Samsun, Kahramanmaraş, Kayseri, and Düzce.

Significant communities live in Jordan,[48] Iraq,[48][49] Syria (in Beer ajam and many other villages),[48] Lebanon, Egypt, Israel (in the villages of Kfar Kama and Rehaniya - for more information see Circassians in Israel),[48] Libya, and Macedonia.[50] A number of Adyghe were introduced to Bulgaria in 1864-1865 but most fled after it became separate from the Ottoman Empire in 1878.

A great number of Adyghe people have also immigrated to the United States and settled in (Upstate New York, California, and New Jersey).

The small community from Kosovo expatriated to Adygea in 1998.

The total number of Adyghe people worldwide is estimated at 6 million.

Notable Adyghes

Gallery

-

A group of Adyghe children in traditional clothes

-

Adyghe dancer

-

Adyghe warriors

-

Adyghe woman

-

Adyghes in the French mandate legion in Syria

-

An Adyghe warrior

-

Adyghe traditional dance group from the Caucasus region

-

Adyghe in Sochi.

-

The fall of Damascus to the Allies, late June 1941. A car carrying the Free French commanders, General Georges Catroux and Major-General Paul Louis Le Gentilhomme, enters the city. They are escorted by Vichy French Circassian cavalry (Gardes Tcherkess).

See also

References

- ^ a b c "Circassia" - Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization

- ^ "Syria" Library of Congress

- ^ a b c d "Circassian World: Responses to the New Challenges" - Sufian Zhemukhov

- ^ Gyula Decsy (1988). Statistical Report on the Languages of the World as of 1985: List of the languages of the world arranged according to continents and countries (Paperback ed.). Eurolingua. p. 62. ISBN 0931922313.

- ^ Gammer, Mos%u030Ce. The Caspian Region: a Re-emerging Region. London [u.a.: Routledge, 2004. Pp. 67

- ^ Adams, Charles J., Wael B. Hallaq, and Donald P. Little. Islamic Studies Presented to Charles J. Adams. Leiden: Brill, 1991. Pp. 194

- ^ "One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups." Questia Online Library. Web. 25 Aug. 2010. Pp. 12

- ^ Pendergast, Sara, and Tom Pendergast. Worldmark Encyclopedia of National Economies. Detroit: Gale Group, 2002. Pp. 241

- ^ Spencer, Edmund. Travels in the Western Caucasus, including a Tour through Imeritia, Mingrelia, Turkey, Moldavia, Galicia, Silesia, and Moravia in 1836. London: H. Colburn, 1838. Pp. 6

- ^ Loewe, Louis. A Dictionary of the Circassian Language: in Two Parts: English-Circassian-Turkish, and Circassian-English-Turkish. London: Bell, 1854. Pp. 5

- ^ The Home Friend: a Weekly Miscellany of Amusement and Instruction. London: Printed for the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1854. Pp. 314

- ^ a b Latham, R. G. Descriptive Ethnology. London: J. Van Voorst, 1859. Pp. 50

- ^ Latham, R. G. Elements of Comparative Philology. London: Walton and Maberly, 1862. Pp. 279

- ^ Latham, R. G. The Nationalities of Europe: Vol. 1-2. London, 1863. Pp. 307

- ^ Klaproth, Julius Von, Frederic Shoberl, and Steven Runciman. Travels in the Caucasus and Georgia: Performed in the Years 1807 and 1808, by Command of the Russian Government. London: Printed for Henry Colburn, and Sold by G. Goldie, Edinburgh, and J. Cumming, Dublin, 1814. Pp. 310

- ^ The British Review, and London Critical Journal. Vol. 6. London: Thoemmes, 1815. Pp. 469

- ^ Taitbout, De Marigny. Three Voyages in the Black Sea to the Coast of Circassia. London, 1837. Pp. 5-6

- ^ Charnock, Richard Stephen. Local Etymology; a Derivative Dictionary of Geographical Names. London: Houlston and Wright, 1859. Pp 69

- ^ Guthrie, William, James Ferguson, and John Knox. A New Geographical, Historical and Commercial Grammar and Present State of the Several Kingdoms of the World ... Philadelphia: Johnson & Warner, 1815. Pp. 549

- ^ Reclus, Élisée, and A. H. Keane. The Earth and Its Inhabitants, Asia: Asiatic Russia. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Historical Microreproductions, 1891. Pp. 55

- ^ Spencer, Edmund. Turkey, Russia, the Black Sea, and Circassia. London: G. Routledge &, 1855. Pp. 347-348

- ^ Golovin, Ivan. The Caucasus. London, 1854. Pp. 81

- ^ Li,, Jun (2008). "Worldwide Human Relationships Inferred from Genome-Wide Patterns of Variation". Science. 319 (5866): 1100–1104. doi:10.1126/science.1153717. PMID 18292342.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Levene 2005:297

- ^ Richmond, Chapter 4

- ^ a b King 2008:94-96

- ^ Shenfield, Stephen D. 1999. The Circassians: a forgotten genocide?. In Levene, Mark and Penny Roberts, eds., The massacre in history. Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books. Series: War and Genocide; 1. 149-162.

- ^ UNPO 2006.

- ^ Neumann 1840

- ^ Shenfield 1999

- ^ Levene 2005:299

- ^ Levene 2005:302

- ^ http://www.ammancity.gov.jo/en/gam/about.asp Via the Official Website of Amman

- ^ http://ammancity100.gov.jo/en/content/story-amman/end-ummayad-era-till-1878 Via GAM Official Website

- ^ http://www.edintattoo.co.uk/news-and-press/jordan-the-tattoo

- ^ http://www.echoesfromjordan.com/performing-group/circassian-honour-guard Via EchoesfromJordan Website

- ^ Meri, Josef W., and Jere L. Bacharach. Medieval Islamic Civilization: an Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge, 2006. p. 156

- ^ Loewe, Louis. A Dictionary of the Circassian Language. London: George Bell, 1854. p. 6

- ^ The Nautical Magazine :. Vol. 23. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent, 1854. p. 154

- ^ Richmond, Walter. The Northwest Caucasus: Past, Present, Future. London: Routledge, 2008. p. 28

- ^ Scott, Walter, and David Hewitt. The Antiquary. Vol. 13. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 1995. pp. 274

- ^ Smith, Sebastian. Allah's Mountains: the Battle for Chechnya. London: TPP, 2006. p. 32

- ^ Taitbout, De Marigny. Three Voyages in the Black Sea to the Coast of Circassia. London, 1837. p. 74

- ^ The Penny Magazine. London: Charles Knight, 1838. p. 138

- ^ Minahan, James. One Europe, Many Nations: a Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2000. p. 354

- ^ http://www.circassianworld.com/AdygheCuisine.pdf (English Language)

- ^ “Адыгэ 1оры1уатэм ухэзгъэгъозэн тхылъ “, Ехъул1э Ат1ыф ,Нахэхэр (129-132) ,гощын (1), Адыгэ ш1уш1э Хасэ, Йордания ,2009. (Arabic Language)"

- ^ a b c d Significant numbers of Adyghe speakers reside in Turkey, Jordan, Iraq, Syria, and Israel.

- ^ Adyghe by country

- ^ Adyghe - ethnologue

- Journal of a residence in Circassia during the years 1837, 1838, and 1839 - Bell, James Stanislaus (English)

- Amjad Jaimoukha, The Circassians: A Handbook, New York: Palgrave, 2001; London: Routledge Curzon, 2001. ISBN 978-0-312-23994-7

- Jaimoukha, Amjad, Circassian Culture and Folklore: Hospitality Traditions, Cuisine, Festivals & Music (Kabardian, Cherkess, Adigean, Shapsugh & Diaspora), Bennett and Bloom, 2010.

External links

English

- Nart Sagas from the Caucasus: Myths and Legends from the Circassians, Abazas, Abkhaz, and Ubykhs. Assembled, translated, and annotated by John Colarusso. (English)

- circassia.blogsome.com ; Only the one independent on net!: information and observations

- More Nart Tales (English)

- Circassian World (English)

- Adyga.org - Most popular circassian internet forum

- Mideast & N. Africa Encyclopedia: Circassians (English)

- Circassians Culture News Video Music Photo Web Portal(English)

- The Cherkess Fund Organization (English)

- Justice For North Caucasus Group (English)

- CCI (Circassian Cultural Institute) (English)

- CEF (Circassian Education Foundation) (English), USA

- Circassian's in California (English), USA

- Mamluk Studies at the University of Chicago (English), USA

- Architecture of the Circassian Mamluks (English)

- EUROXASE (Federation of European Circassians) (English & Turkish), EU

- NART TV (National Adiga Radio & Television) (English & Circassian), Jordan

- KAFSAM (Kafkasya Stratejik Araştırmalar Merkezi) (English & Turkish), Turkey

- Adyghe Khassa Australia Circassian Association Australia (English), Australia

- Short description of the 12 Circassian tribes

- Map of the Diaspora

- Uniting all Adygs, Adyghe world wide network adigafreinds.com

- The Circassian Art official website

Adyghe

Turkish

- Circassians Culture News Video Music Photo Web Portal

- Adige Diaspora Of Turkey

- KAF-DER (Kafkas Derneklery Federasyonu), Turkey

- A Page Of The Circassian Association Of The Netherlands, EU

Arabic

Hebrew

Russian

- http://www.mkra.ru -The Ministry of Culture of Adygheya

- Adyga.org - Circassian Internet Forum

- CircassianNews

- Investment Passport of the Kabardino-Balkaria, Russia

- Circassian Nartic Legends (Russian)

- ETHNO-CAUCASUS (Russian & Abkhazian)

- AdygaAbaza

- Circassian Ring in LiveJournal

- Use dmy dates from January 2011

- History of Kuban

- History of the Caucasus

- Peoples of the Caucasus

- Ethnic groups in Russia

- Muslim communities of Russia

- Ethnic groups in Turkey

- Ethnic groups in Jordan

- Ethnic groups in Iraq

- Ethnic groups in Syria

- Ethnic groups in Israel

- Ethnic groups in the United States

- Ethnic groups in the Middle East

- Ethnic groups in Asia

- Caucasian muhajirs

- Circassian people

- Indigenous peoples of Europe