American Revolutionary War

| American Revolutionary War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: Battle of Bunker Hill, Death of Montgomery at Quebec, Battle of Cowpens, "Moonlight Battle" | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Cherokee | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

...full list |

Joseph Brant ...full list | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

At Height: |

At Height: | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 50,000± American dead and wounded[6] |

20,000± British army dead and wounded

19,740 sailors dead [2] | ||||||||

Template:18th century Atlantic/Mediterranean conflicts involving the United States Template:18th century Asia/Pacific conflicts involving the United States

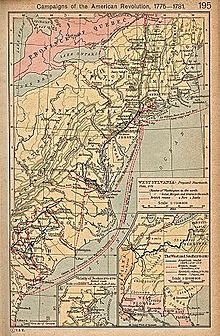

The American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) or American War of Independence,[7] or simply Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.

The war was the result of the political American Revolution, which galvanized around the dispute between the Parliament of Great Britain and colonists opposed to the Stamp Act of 1765, which the Americans protested as unconstitutional. The Parliament insisted on its right to tax colonists; the Americans claimed their rights as Englishmen to no taxation without representation. The Americans formed a unifying Continental Congress and a shadow government in each colony. The American boycott of British tea led to the Boston Tea Party in 1773. London responded by ending self government in Massachusetts and putting it under the control of the army with General Thomas Gage as governor. In April of 1775, Gage sent a contingent of troops out of Boston to seize rebel arms. Local militia, known as 'minutemen,' confronted the British troops and nearly destroyed the British column. The Battles of Lexington and Concord ignited the war. Any chance of a compromise ended when the colonies declared independence and formed a new nation, the United States of America on July 4, 1776.

France, Spain and the Dutch Republic all secretly provided supplies, ammunition and weapons to the revolutionaries starting early in 1776. After early British success, the war became a standoff. The British used their naval superiority to capture and occupy American coastal cities while the rebels largely controlled the countryside, where 90 percent of the population lived. British strategy relied on mobilizing Loyalist militia, and was never fully realized. A British invasion from Canada ended in the capture of the British army at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777. That American victory persuaded France to enter the war openly in early 1778, balancing the two sides' military strength. Spain and the Dutch Republic—French allies—also went to war with Britain over the next two years, threatening an invasion of Great Britain and severely testing British military strength with campaigns in Europe. Spain's involvement culminated in the expulsion of British armies from West Florida, securing the American southern flank.

French involvement proved decisive[8] yet expensive as it ruined France's economy.[9] A French naval victory in the Chesapeake forced a second British army to surrender at the Siege of Yorktown in 1781. In 1783, the Treaty of Paris ended the war and recognized the sovereignty of the United States over the territory bounded roughly by what is now Canada to the north, Florida to the south, and the Mississippi River to the west.[10][11]

Combatants before 1778

American armies and militias

When the war began, the 13 colonies lacked a professional army or navy. Each colony sponsored local militia. Militiamen were lightly armed, had little training, and usually did not have uniforms. Their units served for only a few weeks or months at a time, were reluctant to travel far from home and thus were unavailable for extended operations, and lacked the training and discipline of soldiers with more experience. If properly used, however, their numbers could help the Continental armies overwhelm smaller British forces, as at the battles of Concord, Bennington and Saratoga, and the siege of Boston. Both sides used partisan warfare but the Americans effectively suppressed Loyalist activity when British regulars were not in the area.[12]

Seeking to coordinate military efforts, the Continental Congress established (on paper) a regular army on June 14, 1775, and appointed George Washington as commander-in-chief. The development of the Continental Army was always a work in progress, and Washington used both his regulars and state militia throughout the war.

The United States Marine Corps traces its institutional roots to the Continental Marines of the war, formed at Tun Tavern in Philadelphia, by a resolution of the Continental Congress on November 10, 1775, a date regarded and celebrated as the birthday of the Marine Corps. At the beginning of 1776, Washington's army had 20,000 men, with two-thirds enlisted in the Continental Army and the other third in the various state militias.[13] At the end of the American Revolution in 1783, both the Continental Navy and Continental Marines were disbanded. About 250,000 men served as regulars or as militiamen for the Revolutionary cause in the eight years of the war, but there were never more than 90,000 men under arms at one time.

Armies were small by European standards of the era, largely attributable to limitations such as lack of powder and other logistical capabilities on the American side.[14] It was also difficult for Great Britain to transport troops across the Atlantic and they depended on local supplies that the Patriots tried to cut off. By comparison, Duffy notes that Frederick the Great usually commanded from 23,000 to 50,000 in battle. Both figures pale in comparison to the armies that would be fielded in the early 19th century, where troop formations approached or exceeded 100,000 men.

Loyalists

Historians[15] have estimated that approximately 40 to 45 percent of the colonists supported the rebellion, while 15 to 20 percent remained loyal to the Crown. The rest attempted to remain neutral and kept a low profile.

At least 25,000 Loyalists fought on the side of the British. Thousands served in the Royal Navy. On land, Loyalist forces fought alongside the British in most battles in North America. Many Loyalists fought in partisan units, especially in the Southern theater.[16]

The British military met with many difficulties in maximizing the use of Loyalist factions. British historian Jeremy Black wrote, "In the American war it was clear to both royal generals and revolutionaries that organized and significant Loyalist activity would require the presence of British forces."[17] In the South, the use of Loyalists presented the British with "major problems of strategic choice" since while it was necessary to widely disperse troops in order to defend Loyalist areas, it was also recognized that there was a need for "the maintenance of large concentrated forces able" to counter major attacks from the American forces.[18] In addition, the British were forced to ensure that their military actions would not "offend Loyalist opinion", eliminating such options as attempting to "live off the country", destroying property for intimidation purposes, or coercing payments from colonists ("laying them under contribution").[19]

British armies and auxiliaries

Early in 1775, the British Army consisted of about 36,000 men worldwide, but wartime recruitment steadily increased this number. Great Britain had a difficult time appointing general officers, however. General Thomas Gage, in command of British forces in North America when the rebellion started, was criticized for being too lenient (perhaps influenced by his American wife). General Jeffrey Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst turned down an appointment as commander in chief due to an unwillingness to take sides in the conflict.[20] Similarly, Admiral Augustus Keppel turned down a command, saying "I cannot draw the sword in such a cause." The Earl of Effingham publicly resigned his commission when his 22nd Regiment of foot was posted to America, and William Howe and John Burgoyne were members of parliament who opposed military solutions to the American rebellion. Howe and Henry Clinton stated that they were unwilling participants in the war and were only following orders.[21]

Over the course of the war, Great Britain signed treaties with various German states, which supplied about 30,000 soldiers. Germans made up about one-third of the British troop strength in North America. Hesse-Kassel contributed more soldiers than any other state, and German soldiers became known as "Hessians" to the Americans. Revolutionary speakers called German soldiers "foreign mercenaries," and they are scorned as such in the Declaration of Independence. By 1779, the number of British and German troops stationed in North America was over 60,000, although these were spread from Canada to Florida.[22] About 10,000 Loyalist Americans under arms for the British are included in these figures.[23]

Black Americans

African Americans—slave and free—served on both sides during the war. The British recruited slaves belonging to Patriot masters and promised freedom to those who served. Because of manpower shortages, George Washington lifted the ban on black enlistment in the Continental Army in January 1776. Small all-black units were formed in Rhode Island and Massachusetts; many slaves were promised freedom for serving. Another all-black unit came from Haiti with French forces. At least 5,000 black soldiers fought for the Revolutionary cause.[24]

Tens of thousands of slaves escaped during the war and joined British lines; others simply moved off into the chaos. For instance, in South Carolina, nearly 25,000 slaves (30% of the enslaved population) fled, migrated or died during the disruption of the war.[25] This greatly disrupted plantation production during and after the war. When they withdrew their forces from Savannah and Charleston, the British also evacuated 10,000 slaves, now freedmen.[26] Altogether, the British were estimated to evacuate nearly 20,000 freedmen (including families) with other Loyalists and their troops at the end of the war. More than 3,000 freedmen were resettled in Nova Scotia; others were transported to the West Indies of the Caribbean islands, and some to Great Britain.[27]

Native Americans

Most Native Americans east of the Mississippi River were affected by the war, and many communities were divided over the question of how to respond to the conflict. Though a few tribes were on friendly terms with the Americans, most Native Americans opposed the United States as a potential threat to their territory. Approximately 13,000 Native Americans fought on the British side, with the largest group coming from the Iroquois tribes, who fielded around 1,500 men.[28] The powerful Iroquois Confederacy was shattered as a result of the conflict; although the Confederacy did not take sides, the Seneca, Onondaga, and Cayuga nations sided with the British. Members of the Mohawk fought on both sides. Many Tuscarora and Oneida sided with the colonists. The Continental Army sent the Sullivan Expedition on raids throughout New York to cripple the Iroquois tribes which had sided with the British. Both during and after the war friction between the Mohawk leaders Joseph Louis Cook and Joseph Brant, who had sided with the Americans and the British respectively, further exacerbated the split.

Creek and Seminole allies of Britain fought against Americans in Georgia and South Carolina. In 1778, a force of 800 Creeks destroyed American settlements along the Broad River in Georgia. Creek warriors also joined Thomas Brown's raids into South Carolina and assisted Britain during the Siege of Savannah.[29] Many Native Americans were involved in the fighting between Britain and Spain on the Gulf Coast and up the Mississippi River—mostly on the British side. Thousands of Creeks, Chickasaws, and Choctaws fought in or near major battles such as the Battle of Fort Charlotte, the Battle of Mobile, and the Siege of Pensacola.[30]

Sex, race, class

Pybus (2005) estimates that about 20,000 slaves defected to or were captured by the British, of whom about 8,000 died from disease or wounds or were recaptured by the Patriots, and 12,000 left the country at the end of the war, for freedom in Canada or slavery in the West Indies.[31]

Baller (2006) examines family dynamics and mobilization for the Revolution in central Massachusetts. He reports that warfare and the farming culture were sometimes incompatible. Militiamen found that living and working on the family farm had not prepared them for wartime marches and the rigors of camp life. Rugged individualism conflicted with military discipline and regimentation. A man's birth order often influenced his military recruitment, as younger sons went to war and older sons took charge of the farm. A person's family responsibilities and the prevalent patriarchy could impede mobilization. Harvesting duties and family emergencies pulled men home regardless of the sergeant's orders. Some relatives might be Loyalists, creating internal strains. On the whole, historians conclude the Revolution's effect on patriarchy and inheritance patterns favored egalitarianism.[32]

McDonnell, (2006) shows a grave complication in Virginia's mobilization of troops was the conflicting interests of distinct social classes, which tended to undercut a unified commitment to the Patriot cause. The Assembly balanced the competing demands of elite slaveowning planters, the middling yeomen (some owning a few slaves), and landless indentured servants, among other groups. The Assembly used deferments, taxes, military service substitute, and conscription to resolve the tensions. Unresolved class conflict, however, made these laws less effective. There were violent protests, many cases of evasion, and large-scale desertion, so that Virginia's contributions came at embarrassingly low levels. With the British invasion of the state in 1781, Virginia was mired in class divisiveness as its native son, George Washington, made desperate appeals for troops.[33]

War in the north, 1775–1780

Massachusetts

Before the war, Boston had been the center of much revolutionary activity, leading to the punitive Massachusetts Government Act in 1774 that ended local government. Popular resistance to these measures, however, compelled the newly appointed royal officials in Massachusetts to resign or to seek refuge in Boston. Lieutenant General Thomas Gage, the British North American commander-in chief, commanded four regiments of British regulars (about 4,000 men) from his headquarters in Boston, but the countryside was in the hands of the Revolutionaries.

On the night of April 18, 1775, General Gage sent 700 men to seize munitions stored by the colonial militia at Concord, Massachusetts. Riders including Paul Revere alerted the countryside, and when British troops entered Lexington on the morning of April 19, they found 77 minutemen formed up on the village green. Shots were exchanged, killing several minutemen. The British moved on to Concord, where a detachment of three companies was engaged and routed at the North Bridge by a force of 500 minutemen. As the British retreated back to Boston, thousands of militiamen attacked them along the roads, inflicting great damage before timely British reinforcements prevented a total disaster. With the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the war had begun.

The militia converged on Boston, bottling up the British in the city. About 4,500 more British soldiers arrived by sea, and on June 17, 1775, British forces under General William Howe seized the Charlestown peninsula at the Battle of Bunker Hill. The Americans fell back, but British losses were so heavy that the attack was not followed up. The siege was not broken, and Gage was soon replaced by Howe as the British commander-in-chief.[34]

In July 1775, newly appointed General Washington arrived outside Boston to take charge of the colonial forces and to organize the Continental Army. Realizing his army's desperate shortage of gunpowder, Washington asked for new sources. Arsenals were raided and some manufacturing was attempted; 90% of the supply (2 million pounds) was imported by the end of 1776, mostly from France.[35] Patriots in New Hampshire had seized powder, muskets and cannon from Fort William and Mary in Portsmouth Harbor in late 1774.[36] Some of the munitions were used in the Boston campaign.

The standoff continued throughout the fall and winter. In early March 1776, heavy cannons that the patriots had captured at Fort Ticonderoga were brought to Boston by Colonel Henry Knox, and placed on Dorchester Heights. Since the artillery now overlooked the British positions, Howe's situation was untenable, and the British fled on March 17, 1776, sailing to their naval base at Halifax, Nova Scotia.[37] Washington then moved most of the Continental Army to fortify New York City.

Quebec

Three weeks after the siege of Boston began, a troop of militia volunteers led by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold captured Fort Ticonderoga, a strategically important point on Lake Champlain between New York and the Province of Quebec. After that action they also raided Fort St. John's, not far from Montreal, which alarmed the population and the authorities there. In response, Quebec's governor Guy Carleton began fortifying St. John's, and opened negotiations with the Iroquois and other Native American tribes for their support. These actions, combined with lobbying by both Allen and Arnold and the fear of a British attack from the north, eventually persuaded the Congress to authorize an invasion of Quebec, with the goal of driving the British military from that province. (Quebec was then frequently referred to as Canada, as most of its territory included the former French Province of Canada.)[38]

Two Quebec-bound expeditions were undertaken. On September 28, 1775, Brigadier General Richard Montgomery marched north from Fort Ticonderoga with about 1,700 militiamen, besieging and capturing Fort St. Jean on November 2 and then Montreal on November 13. General Carleton escaped to Quebec City and began preparing that city for an attack. The second expedition, led by Colonel Arnold, went through the wilderness of what is now northern Maine. Logistics were difficult, with 300 men turning back, and another 200 perishing due to the harsh conditions. By the time Arnold reached Quebec City in early November, he had but 600 of his original 1,100 men. Montgomery's force joined Arnold's, and they attacked Quebec City on December 31, but were defeated by Carleton in a battle that ended with Montgomery dead, Arnold wounded, and over 400 Americans taken prisoner.[39] The remaining Americans held on outside Quebec City until the spring of 1776, suffering from poor camp conditions and smallpox, and then withdrew when a squadron of British ships under Captain Charles Douglas arrived to relieve the siege.[40]

Another attempt was made by the Americans to push back towards Quebec, but they failed at Trois-Rivières on June 8, 1776. Carleton then launched his own invasion and defeated Arnold at the Battle of Valcour Island in October. Arnold fell back to Fort Ticonderoga, where the invasion had begun. While the invasion ended as a disaster for the Americans, Arnold's efforts in 1776 delayed a full-scale British counteroffensive until the Saratoga campaign of 1777.

The invasion cost the Americans their base of support in British public opinion, "So that the violent measures towards America are freely adopted and countenanced by a majority of individuals of all ranks, professions, or occupations, in this country."[41] It gained them at best limited support in the population of Quebec, which, while somewhat supportive early in the invasion, became less so later during the occupation, when American policies against suspected Loyalists became harsher, and the army's hard currency ran out. Two small regiments of Canadiens were recruited during the operation, and they were with the army on its retreat back to Ticonderoga.[42]

New York and New Jersey

Having withdrawn his army from Boston, General Howe now focused on capturing New York City, which then was limited to the southern tip of Manhattan Island. To defend the city, General Washington spread about 20,000 soldiers along the shores of New York's harbor, concentrated on Long Island and Manhattan.[43] While British and recently hired Hessian troops were assembling across the upper harbor on Staten Island for the campaign, and Washington had the newly issued Declaration of American Independence read to his men.[44] No longer was there any possibility of compromise. On August 27, 1776, after landing about 22,000 men on Long Island, the British drove the Americans back to Brooklyn Heights, securing a decisive British victory in the largest battle of the entire Revolution. Howe then laid siege to fortifications there. In a feat considered by many historians to be one of his most impressive actions as Commander in Chief, Washington personally directed the withdrawal of his entire remaining army and all their supplies across the East River in one night without discovery by the British or significant loss of men and materiel.[45]

After a failed peace conference on September 11, Howe resumed the attack. On September 15, Howe landed about 12,000 men on lower Manhattan, quickly taking control of New York City. The Americans withdrew north up the island to Harlem Heights, where they skirmished the next day but held their ground. When Howe moved to encircle Washington's army in October, the Americans again fell back, and a battle at White Plains was fought on October 28.[46] Again Washington retreated, and Howe returned to Manhattan and captured Fort Washington in mid November, taking about 2,000 prisoners (with an additional 1,000 having been captured during the battle for Long Island). Thus began the infamous "prison ships" system the British maintained in New York for the rest of the war, in which more American soldiers and sailors died of neglect than died in every battle of the entire war, combined.[47][48][49][50][51]

Howe then detached General Clinton to seize Newport, Rhode Island, while General Lord Cornwallis continued to chase Washington's army through New Jersey, until the Americans withdrew across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania in early December.[52] With the campaign at an apparent conclusion for the season, the British entered winter quarters. Although Howe had missed several opportunities to crush the diminishing American army, he had killed or captured over 5,000 Americans.

The outlook of the Continental Army was bleak. "These are the times that try men's souls," wrote Thomas Paine, who was with the army on the retreat.[53] The army had dwindled to fewer than 5,000 men fit for duty, and would be reduced to 1,400 after enlistments expired at the end of the year.[citation needed] Congress had abandoned Philadelphia in despair, although popular resistance to British occupation was growing in the countryside.[54]

Washington decided to take the offensive, stealthily crossing the Delaware on Christmas night and capturing nearly 1,000 Hessians at the Battle of Trenton on December 26, 1776.[55] Cornwallis marched to retake Trenton but was first repulsed and then outmaneuvered by Washington, who successfully attacked the British rearguard at Princeton on January 3, 1777.[56] Washington then entered winter quarters at Morristown, New Jersey, having given a morale boost to the American cause. New Jersey militia continued to harass British and Hessian forces throughout the winter, forcing the British to retreat to their base in and around New York City.[57]

At every stage the British strategy assumed a large base of Loyalist supporters would rally to the King given some military support. In February 1776 Clinton took 2,000 men and a naval squadron to invade North Carolina, which he called off when he learned the Loyalists had been crushed at the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge. In June he tried to seize Charleston, South Carolina, the leading port in the South, hoping for a simultaneous rising in South Carolina. It seemed a cheap way of waging the war but it failed as the naval force was defeated by the forts and because no local Loyalists attacked the town from behind. The Loyalists were too poorly organized to be effective, but as late as 1781 senior officials in London, misled by Loyalist exiles, placed their confidence in their rising. [citation needed]

Saratoga and Philadelphia

When the British began to plan operations for 1777, they had two main armies in North America: Carleton's army in Quebec, and Howe's army in New York. In London, Lord George Germain approved campaigns for these armies which, because of miscommunication, poor planning, and rivalries between commanders, did not work in conjunction. Although Howe successfully captured Philadelphia, the northern army was lost in a disastrous surrender at Saratoga. Both Carleton and Howe resigned after the 1777 campaign.

Saratoga campaign

The first of the 1777 campaigns was an expedition from Quebec led by General John Burgoyne. The goal was to seize the Lake Champlain and Hudson River corridor, effectively isolating New England from the rest of the American colonies. Burgoyne's invasion had two components: he would lead about 8,000 men along Lake Champlain towards Albany, New York, while a second column of about 2,000 men, led by Barry St. Leger, would move down the Mohawk River Valley and link up with Burgoyne in Albany, New York.[58]

Burgoyne set off in June, and recaptured Fort Ticonderoga in early July. Thereafter, his march was slowed by the Americans who literally knocked down trees in his path, and by his army's extensive baggage train. A detachment sent out to seize supplies was decisively defeated in the Battle of Bennington by American militia in August, depriving Burgoyne of nearly 1,000 men.

Meanwhile, St. Leger—more than half of his force Native Americans led by Sayenqueraghta—had laid siege to Fort Stanwix. American militiamen and their Native American allies marched to relieve the siege but were ambushed and scattered at the Battle of Oriskany. When a second relief expedition approached, this time led by Benedict Arnold, St. Leger's Indian support abandoned him, forcing him to break off the siege and return to Quebec.

Burgoyne's army had been reduced to about 6,000 men by the loss at Bennington and the need to garrison Ticonderoga, and he was running short on supplies.[59] Despite these setbacks, he determined to push on towards Albany. An American army of 8,000 men, commanded by the General Horatio Gates, had entrenched about 10 miles (16 km) south of Saratoga, New York. Burgoyne tried to outflank the Americans but was checked at the first battle of Saratoga in September. Burgoyne's situation was desperate, but he now hoped that help from Howe's army in New York City might be on the way. It was not: Howe had instead sailed away on his expedition to capture Philadelphia. American militiamen flocked to Gates' army, swelling his force to 11,000 by the beginning of October. After being badly beaten at the second battle of Saratoga, Burgoyne surrendered on October 17.

Saratoga was the turning point of the war. Revolutionary confidence and determination, suffering from Howe's successful occupation of Philadelphia, was renewed. What is more important, the victory encouraged France to make an open alliance with the Americans, after two years of semi-secret support. For the British, the war had now become much more complicated.[60]

Philadelphia campaign

Having secured New York City in 1776, General Howe concentrated on capturing Philadelphia, the seat of the Revolutionary government, in 1777. He moved slowly, landing 15,000 troops in late August at the northern end of Chesapeake Bay. Washington positioned his 11,000 men between Howe and Philadelphia but was driven back at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. The Continental Congress again abandoned Philadelphia, and on September 26, Howe finally outmaneuvered Washington and marched into the city unopposed. Washington unsuccessfully attacked the British encampment in nearby Germantown in early October and then retreated to watch and wait.

After repelling a British attack at White Marsh, Washington and his army encamped at Valley Forge in December 1777, about 20 miles (32 km) from Philadelphia, where they stayed for the next six months. Over the winter, 2,500 men (out of 10,000) died from disease and exposure. The next spring, however, the army emerged from Valley Forge in good order, thanks in part to a training program supervised by Baron von Steuben, who introduced the most modern Prussian methods of organization and tactics.[citation needed]

General Clinton replaced Howe as British commander-in-chief. French entry into the war had changed British strategy, and Clinton abandoned Philadelphia to reinforce New York City, now vulnerable to French naval power. Washington shadowed Clinton on his withdrawal and forced a strategic victory at the battle at Monmouth on June 28, 1778, the last major battle in the north. Clinton's army went to New York City in July, arriving just before a French fleet under Admiral d'Estaing arrived off the American coast. Washington's army returned to White Plains, New York, north of the city. Although both armies were back where they had been two years earlier, the nature of the war had now changed.[61]

An international war, 1778–1783

In 1778, the war over the rebellion in North America became international, spreading not only to Europe but to European colonies in the West Indies and in India. From 1776 France had informally been involved, with French admiral Latouche Tréville having provided supplies, ammunition and guns from France to the United States after Thomas Jefferson had encouraged a French alliance, and guns such as de Valliere type were used, playing an important role in such battles as the Battle of Saratoga.[62] George Washington wrote about the French supplies and guns in a letter to General Heath on May 2, 1777. After learning of the American victory at Saratoga, France signed the Treaty of Alliance with the United States on February 6, 1778, formalizing the Franco-American alliance negotiated by Benjamin Franklin. Spain entered the war as an ally of France in June 1779, a renewal of the Bourbon Family Compact. Unlike France, Spain initially refused to recognize the independence of the United States, because Spain was not keen on encouraging similar anti-colonial rebellions in the Spanish Empire. Both countries had quietly provided assistance to the Americans since the beginning of the war, hoping to dilute British power. So too had the Dutch Republic, which was formally brought into the war at the end of 1780.[63]

Punish the Americans

In London King George III gave up all hope of subduing America by more armies, while Britain had a European war to fight. "It was a joke," he said, "to think of keeping Pennsylvania." There was no hope of recovering New England. But the King was still determined "never to acknowledge the independence of the Americans, and to punish their contumacy by the indefinite prolongation of a war which promised to be eternal."[64] His plan was to keep the 30,000 men garrisoned in New York, Rhode Island, Quebec, and Florida; other forces would attack the French and Spanish in the West Indies. To punish the Americans the King planned to destroy their coasting-trade, bombard their ports; sack and burn towns along the coast (as Benedict Arnold did to New London, Connecticut in 1781), and turn loose the Native Americans to attack civilians in frontier settlements. These operations, the King felt, would inspire the Loyalists; would splinter the Congress; and "would keep the rebels harassed, anxious, and poor, until the day when, by a natural and inevitable process, discontent and disappointment were converted into penitence and remorse" and they would beg to return to his authority.[65] The plan meant destruction for the Loyalists and loyal Native Americans, an indefinite prolongation of a costly war, and the risk of disaster as the French and Spanish assembled an armada to invade the British Isles. The British planned to re-subjugate the rebellious colonies after dealing with the Americans' European allies.

Widening of the naval war

When the war began, the British had overwhelming naval superiority over the American colonists. The Royal Navy had over 100 ships of the line and many frigates and smaller craft, although this fleet was old and in poor condition, a situation which would be blamed on Lord Sandwich, the First Lord of the Admiralty. During the first three years of the war, the Royal Navy was primarily used to transport troops for land operations and to protect commercial shipping. The American colonists had no ships of the line, and relied extensively on privateering to harass British shipping. The privateers caused worry disproportionate to their material success, although those operating out of French channel ports before and after France joined the war caused significant embarrassment to the Royal Navy and inflamed Anglo-French relations. About 55,000 American sailors served aboard the privateers during the war.[66] The American privateers had almost 1,700 ships, and they captured 2,283 enemy ships.[67] The Continental Congress authorized the creation of a small Continental Navy in October 1775, which was primarily used for commerce raiding. John Paul Jones became the first great American naval hero, capturing HMS Drake on April 24, 1778, the first victory for any American military vessel in British waters.[68]

France's formal entry into the war meant that British naval superiority was now contested. The Franco-American alliance began poorly, however, with failed operations at Rhode Island in 1778 and Savannah, Georgia, in 1779. Part of the problem was that France and the United States had different military priorities: France hoped to capture British possessions in the West Indies before helping to secure American independence. While French financial assistance to the American war effort was already of critical importance, French military aid to the Americans would not show positive results until the arrival in July 1780 of a large force of soldiers led by the Comte de Rochambeau.

Spain entered the war as a French ally with the goal of recapturing Gibraltar and Minorca, which it had lost to the British in 1704. Gibraltar was besieged for more than three years, but the British garrison stubbornly resisted and was resupplied twice: once after Admiral Rodney's victory over Juan de Lángara in the 1780 "Moonlight Battle", and again after Admiral Richard Howe fought Luis de Córdova y Córdova to a draw in the Battle of Cape Spartel. Further Franco-Spanish efforts to capture Gibraltar were unsuccessful. One notable success took place on February 5, 1782, when Spanish and French forces captured Minorca, which Spain retained after the war. Ambitious plans for an invasion of Great Britain in 1779 had to be abandoned.

West Indies and Gulf Coast

There was much action in the West Indies, especially in the Lesser Antilles. Although France lost St. Lucia early in the war, its navy dominated the West Indies, capturing Dominica, Grenada, Saint Vincent, Montserrat, Tobago and St. Kitts. Dutch possessions in the West Indies and South America were captured by Britain but later recaptured by France and restored to the Dutch Republic. France successfully conquered the Turks and Caicos archipelago. At the Battle of the Saintes in April 1782, a victory by Rodney's fleet over the French Admiral de Grasse frustrated the hopes of France and Spain to take Jamaica and other colonies from the British. [citation needed]

On the Gulf Coast, Count Bernardo de Gálvez, the Spanish governor of Louisiana, quickly removed the British from their outposts on the lower Mississippi River in 1779 in actions at Manchac and Baton Rouge in British West Florida. Gálvez then captured Mobile in 1780 and stormed and captured the British citadel and capital of Pensacola in 1781. On May 8, 1782, Gálvez captured the British naval base at New Providence in the Bahamas; it was ceded by Spain after the Treaty of Paris and simultaneously recovered by British Loyalists in 1783. Gálvez' actions led to the Spanish acquisition of East and West Florida in the peace settlement, denied the British the opportunity of encircling the American rebels from the south, and kept open a vital conduit for supplies to the American frontier. The Continental Congress cited Gálvez in 1785 for his aid during the revolution and George Washington took him to his right during the first parade of July 4.[69]

Central America was also subject to conflict between Britain and Spain, as Britain sought to expand its influence beyond coastal logging and fishing communities in present-day Belize, Honduras, and Nicaragua. Expeditions against San Fernando de Omoa in 1779 and San Juan in 1780 (the latter famously led by a young Horatio Nelson) met with only temporary success before being abandoned due to disease. The Spanish colonial leaders, in turn, could not completely eliminate British influences along the Mosquito Coast. Except for the French acquisition of Tobago, sovereignty in the West Indies was returned to the status quo ante bellum in the peace of 1783.

India and the Netherlands

Template:Campaignbox American War of Independence: East Indies

When word reached India in 1778 that France had entered the war, British military forces moved quickly to capture French colonial outposts there, capturing Pondicherry after two months of siege.[70] The capture of the French-controlled port of Mahé on India's west coast motivated Mysore's ruler, Hyder Ali (who was already upset at other British actions, and benefited from trade through the port), to open the Second Anglo-Mysore War in 1780. Ali, and later his son Tipu Sultan, almost drove the British from southern India but was frustrated by weak French support, and the war ended status quo ante bellum with the 1784 Treaty of Mangalore. French opposition was led in 1782 and 1783 by Admiral the Baillie de Suffren, who recaptured Trincomalee from the British and fought five celebrated, but largely inconclusive, naval engagements against British Admiral Sir Edward Hughes.[71] France's Indian colonies were returned after the war.

The Dutch Republic, nominally neutral, had been trading with the Americans, exchanging Dutch arms and munitions for American colonial wares (in contravention of the British Navigation Acts), primarily through activity based in St. Eustatius, before the French formally entered the war.[72] The British considered this trade to include contraband military supplies and had attempted to stop it, at first diplomatically by appealing to previous treaty obligations, interpretation of whose terms the two nations disagreed on, and then by searching and seizing Dutch merchant ships. The situation escalated when the British seized a Dutch merchant convoy sailing under Dutch naval escort in December 1779, prompting the Dutch to join the League of Armed Neutrality. Britain responded to this decision by declaring war on the Dutch in December 1780, sparking the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War.[73] The war was a military and economic disaster for the Dutch Republic. Paralyzed by internal political divisions, it could not respond effectively to British blockades of its coast and the capture of many of its colonies. In the 1784 peace treaty between the two nations, the Dutch lost the Indian port of Negapatam and were forced to make trade concessions.[74] The Dutch Republic signed a friendship and trade agreement with the United States in 1782, and was the second country (after France) to formally recognize the United States.[75]

Southern theater

During the first three years of the American Revolutionary War, the primary military encounters were in the north, although some attempts to organize Loyalists were defeated, a British attempt at Charleston, South Carolina failed, and a variety of efforts to attack British forces in East Florida failed. After French entry into the war, the British turned their attention to the southern colonies, where they hoped to regain control by recruiting Loyalists. This southern strategy also had the advantage of keeping the Royal Navy closer to the Caribbean, where the British needed to defend economically important possessions against the French and Spanish.[76]

On December 29, 1778, an expeditionary corps from Clinton's army in New York captured Savannah, Georgia. An attempt by French and American forces to retake Savannah failed on October 9, 1779. Clinton then besieged Charleston, capturing it and most of the southern Continental Army on May 12, 1780. With relatively few casualties, Clinton had seized the South's biggest city and seaport, providing a base for further conquest.[77]

The remnants of the southern Continental Army began to withdraw to North Carolina but were pursued by Lt. Colonel Banastre Tarleton, who defeated them at the Waxhaws on May 29, 1780. With these events, organized American military activity in the region collapsed, though the war was carried on by partisans such as Francis Marion. Cornwallis took over British operations, while Horatio Gates arrived to command the American effort. On August 16, 1780, Gates was defeated at the Battle of Camden, setting the stage for Cornwallis to invade North Carolina.[78]

Cornwallis' victories quickly turned, however. One wing of his army was utterly defeated at the Battle of Kings Mountain on October 7, 1780, and Tarleton was decisively defeated by Daniel Morgan at the Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781. General Nathanael Greene, who replaced General Gates, proceeded to wear down the British in a series of battles, each of them tactically a victory for the British but giving no strategic advantage to the victors. Greene summed up his approach in a motto that would become famous: "We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again." By March, Greene's army had grown to the point where he felt that he could face Cornwallis directly. In the key Battle of Guilford Court House, Cornwallis defeated Greene, but at tremendous cost, and without breaking Greene's army. He retreated to Wilmington, North Carolina for resupply and reinforcement, after which he moved north into Virginia, leaving the Carolinas and Georgia open to Greene.[79]

In January 1781, a British force under Benedict Arnold landed in Virginia, and began moving through the Virginia countryside, destroying supply depots, mills, and other economic targets. In February, General Washington dispatched General Lafayette to counter Arnold, later also sending General Anthony Wayne. Arnold was reinforced with additional troops from New York in March, and his army was joined with that of Cornwallis in May. Lafayette skirmished with Cornwallis, avoiding a decisive battle while gathering reinforcements. Cornwallis could not trap Lafayette, and upon his arrival at Williamsburg in June, received orders from General Clinton to establish a fortified naval base in Virginia. Following these orders, he fortified Yorktown, and, shadowed by Lafayette, awaited the arrival of the Royal Navy.[80]

Northern and western frontier

West of the Appalachian Mountains and along the border with Quebec, the American Revolutionary War was an "Indian War". Most Native Americans supported the British. Like the Iroquois Confederacy, tribes such as the Shawnee split into factions, and the Chickamauga split off from the rest of the Cherokee over differences regarding peace with the Americans. The British supplied their native allies with muskets, gunpowder and advice, while Loyalists led raids against civilian settlements, especially in New York, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania. Joint Iroquois-Loyalist attacks in the Wyoming Valley and at Cherry Valley in 1778 provoked Washington to send the Sullivan Expedition into western New York during the summer of 1779. There was little fighting as Sullivan systematically destroyed the Indians' winter food supplies, forcing them to flee permanently to British bases in Quebec and the Niagara Falls area.[81]

In the Ohio Country and the Illinois Country, the Virginia frontiersman George Rogers Clark attempted to neutralize British influence among the Ohio tribes by capturing the outposts of Kaskaskia and Cahokia and Vincennes in the summer of 1778. When General Henry Hamilton, the British commander at Detroit, retook Vincennes, Clark returned in a surprise march in February 1779 and captured Hamilton.[82]

In March 1782, Pennsylvania militiamen killed about a hundred neutral Native Americans in the Gnadenhütten massacre. In the last major encounters of the war, a force of 200 Kentucky militia was defeated at the Battle of Blue Licks in August 1782.

Yorktown and the surrender of Cornwallis

The northern, southern, and naval theaters of the war converged in 1781 at Yorktown, Virginia. Cornwallis, having been ordered to occupy a fortified position that could be resupplied (and evacuated, if necessary) by sea, had settled in Yorktown, on the York River, which was navigable by sea-going vessels. Aware that the arrival of the French fleet from the West Indies would give the allies control of the Chesapeake, Washington began moving the American and French forces south toward Virginia in August. In early September, French naval forces defeated a British fleet at the Battle of the Chesapeake, cutting off Cornwallis' escape. When Washington arrived outside Yorktown, the combined Franco-American force of 18,900 men began besieging Cornwallis in early October. For several days, the French and Americans bombarded the British defenses, and then began taking the outer positions. Cornwallis decided his position was becoming untenable, and he surrendered his entire army of over 7,000 men on October 19, 1781.[83]

With the surrender at Yorktown, King George lost control of Parliament to the peace party, and there were no further major military activities in North America. The British had 30,000 garrison troops occupying New York City, Charleston, and Savannah.[84] The war continued elsewhere, including the siege of Gibraltar and naval operations in the East and West Indies, until peace was agreed in 1783.

Treaty of Paris

In London, as political support for the war plummeted after Yorktown, British Prime Minister Lord North resigned in March 1782. In April 1782, the Commons voted to end the war in America. Preliminary peace articles were signed in Paris at the end of November, 1782; the formal end of the war did not occur until the Treaty of Paris (for the U.S.) and the Treaties of Versailles (for the other Allies) were signed on September 3, 1783. The last British troops left New York City on November 25, 1783, and the United States Congress of the Confederation ratified the Paris treaty on January 14, 1784.[85]

Britain negotiated the Paris peace treaty without consulting her Native American allies and ceded all Native American territory between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River to the United States. Full of resentment, Native Americans reluctantly confirmed these land cessions with the United States in a series of treaties, but the fighting would be renewed in conflicts along the frontier in the coming years, the largest being the Northwest Indian War.[86] The British would continue to support the Indians against the new American nation especially when hostilities resumed 29 years later in the War of 1812.

The United States gained more than it expected, thanks to the award of western territory. The other Allies had mixed-to-poor results. France did win revenge over hated England, but its material gains were minimal and its financial losses huge. It was already in financial trouble and its borrowing to pay for the war used up all its credit and created the financial disasters that marked the 1780s. Historians link those disasters to the coming of the French Revolution. The Dutch clearly lost on all points. The Spanish had a mixed result; they did not achieve their primary war goal (recovery of Gibraltar), but they did gain territory. However in the long run, as the case of Florida shows, the new territory was of little or no value.[87]

Historical assessment

Advantages and disadvantages of the opposing sides

The Americans began the war with significant disadvantages compared to the British. They had no national government, no national army or navy, and no financial system, no banks, no established credit, and no functioning government departments, such as a treasury. The Congress tried to handle administrative affairs through legislative committees, which proved inefficient. At first, the Americans had no international allies. However the American cause eventually attracted alliances and supporters, especially from France, the Netherlands, and Spain. The British had no supporters throughout the conflict, apart from small German states that were willing to send troops ("Hessians") to do much of the fighting. The Americans had a large, relatively prosperous population (when compared to other colonies) that depended not on imports but on local production for food and most supplies. They were on their home ground, had a smoothly functioning, well organized system of local and state governments, newspapers and printers, and internal lines of communications. They had a long-established system of local militia, with companies and an officer corps that could form the basis of local militias, and provide a training ground for the national army that the Congress set up.[88]

Britain had a large, efficient, and well-financed government, with good credit, and the largest and best navy in the world. Its army was relatively small, but the officer corps and noncommissioned officers were professionals with high levels of skill and many years of experience. Distance was a major problem: most troops and supplies had to be shipped across the Atlantic Ocean. The British usually had logistical problems whenever they operated away from port cities. Additionally, ocean travel meant that British communications were always about two months out of date: by the time British generals in America received their orders from London, the military situation had usually changed.[89]

Suppressing a rebellion in America also posed other problems. Since the colonies covered a large area and had not been united before the war, there was no central area of strategic importance. In Europe, the capture of a capital often meant the end of a war; in America, when the British seized cities such as New York, Philadelphia or Boston, the war continued unabated. Furthermore, the large size of the colonies meant that the British lacked the manpower to control them by force. Once any area had been occupied, troops had to be kept there or the Revolutionaries would regain control, and these troops were thus unavailable for further offensive operations. In addition, despite the professionalism and discipline of the British troops, unfamiliar guerrilla warfare and skirmishing greatly hindered their gains early on. The British had sufficient troops to defeat the Americans on the battlefield but not enough to simultaneously occupy the colonies. This manpower shortage became critical after French and Spanish entry into the war, because British troops had to be dispersed in several theaters, where previously they had been concentrated in America.[90]

The British also had the difficult task of fighting the war while simultaneously retaining the allegiance of Loyalists. Loyalist support was important, since the goal of the war was to keep the colonies in the British Empire, but this imposed numerous military limitations. Early in the war, the Howe brothers served as peace commissioners while simultaneously conducting the war effort, a dual role which may have limited their effectiveness. Additionally, the British could have recruited more slaves and Native Americans to fight the war, but this would have alienated many Loyalists, even more so than the controversial hiring of German mercenaries. The need to retain Loyalist allegiance also meant that the British could not use the harsh methods of suppressing rebellion they employed in Ireland and Scotland. Even with these limitations, many potentially neutral colonists were nonetheless driven into the ranks of the Revolutionaries because of the war.[91]

Costs of the war

Casualties

The total loss of life resulting from the American Revolutionary War is unknown. As was typical in the wars of the era, disease claimed more lives than battle. Between 1775 and 1782, a smallpox epidemic raged across much of North America, killing more than 130,000 people. Historian Joseph Ellis suggests that Washington's decision to have his troops inoculated against the smallpox epidemic was one of his most important decisions.[92]

More than 25,000 American Revolutionaries died during active military service. About 8,000 of these deaths were in battle; the other 17,000 recorded deaths were from disease, including about 8,000–12,000 who died of starvation or disease brought on by deplorable conditions while prisoners of war,[93] most in rotting British prison ships in New York. This tally of deaths from disease is undoubtedly too low, however; 2,500 Americans died while encamped at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777-78 alone. The number of Revolutionaries seriously wounded or disabled by the war has been estimated from 8,500 to 25,000. The total American military casualty figure was therefore as high as 50,000.[94]

About 171,000 sailors served for the British during the war; about 25 to 50 percent of them had been pressed into service. About 1,240 were killed in battle, while 18,500 died from disease. The greatest killer was scurvy, a disease known to be easily preventable by issuing lemon juice to sailors. About 42,000 British sailors deserted during the war.[95]

Approximately 1,200 Germans were killed in action and 6,354 died from illness or accident. About 16,000 of the remaining German troops returned home, but roughly 5,500 remained in the United States after the war for various reasons, many eventually becoming American citizens. No reliable statistics exist for the number of casualties among other groups, including Loyalists, British regulars, Native Americans, French and Spanish troops, and civilians.

Financial costs

The British spent about £80 million and ended with a national debt of £250 million, which it easily financed at about £9.5 million a year in interest. The French spent 1.3 billion livres (about £56 million). Their total national debt was £187 million, which they could not easily finance; over half the French national revenue went to debt service in the 1780s. The debt crisis became a major enabling factor of the French Revolution as the government could not raise taxes without public approval.[96] The United States spent $37 million at the national level plus $114 million by the states. This was mostly covered by loans from France and the Netherlands, loans from Americans, and issuance of an increasing amount of paper money (which became "not worth a continental.") The U.S. finally solved its debt and currency problems in the 1790s when Alexander Hamilton spearheaded the establishment of the First Bank of the United States.[97]

See also

- George Washington in the American Revolution

- Battles of the American Revolutionary War

- Diplomacy in the American Revolutionary War

- History of the United States of America

- Intelligence in the American Revolutionary War

- List of British Forces in the American Revolutionary War

- List of Continental Forces in the American Revolutionary War

- List of revolutions and rebellions

- Category:American Revolution media

Notes

To avoid duplication, notes for sections with a link to a "Main article" will be found in the linked article.

- ^ Montero[clarification needed] p. 356

- ^ a b c Mackesy (1964), pp. 6, 176 (British seamen)

- ^ A. J. Berry, A Time of Terror (2006) p. 252

- ^ Claude, Van Tyne, The loyalists in the American Revolution (1902) pp. 182–3.

- ^ Greene and Pole (1999), p. 393; Boatner (1974), p. 545

- ^ American dead and wounded: Shy, pp. 249–50. The lower figure for number of wounded comes from Chambers, p. 849.

- ^ British writers generally favor "American War of Independence", "American Rebellion", or "War of American Independence". See Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Bibliography at the Michigan State University for usage in titles.

- ^ Greene and Pole, A companion to the American Revolution p 357

- ^ Jonathan R. Dull, A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution (1987) p. 161

- ^ Dull, A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution ch 18

- ^ Lawrence S. Kaplan, "The Treaty of Paris, 1783: A Historiographical Challenge," International History Review, Sept 1983, Vol. 5 Issue 3, pp 431-442

- ^ Black (2001), p. 59. On militia see Boatner (1974), p. 707, and Weigley (1973), ch. 2.

- ^ Crocker (2006), p. 51

- ^ Boatner (1974), p. 264 says the largest force Washington commanded was "under 17,000"; Duffy (1987), p. 17, estimates Washington's maximum was "only 13,000 troops".

- ^ Greene and Pole (1999), p. 235

- ^ Savas and Dameron (2006), p. xli

- ^ Black (2001), p. 12

- ^ Black (2001), p. 13–14

- ^ Black (2001), p. 14

- ^ Ketchum (1997), p. 76

- ^ Ketchum (1997), p. 77

- ^ Black (2001), pp. 27–29; Boatner (1974), pp. 424–26

- ^ Weintraub (2005), p. 240; figure for 1780.

- ^ Kaplan and Kaplan (1989), pp. 64–69 (Revolutionary all-black units)

- ^ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery: 1619–1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1994, p. 73

- ^ Kolchin, p.73

- ^ ""African Americans In The Revolutionary Period, American Revolution

- ^ Greene and Pole (1999), p. 393; Boatner (1974), p. 545

- ^ Ward, Harry M. (1999). The war for independence and the transformation of American society. Psychology Press. p. 198. ISBN 9781857286564. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ O'Brien, Greg (30 April 2008). Pre-removal Choctaw history: exploring new paths. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 123–126. ISBN 9780806139166. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ Cassadra Pybus, "Jefferson's Faulty Math: the Question of Slave Defections in the American Revolution." William and Mary Quarterly 2005 62(2): 243-264. Issn: 0043-5597 Fulltext: in History Cooperative

- ^ William Baller, "Farm Families and the American Revolution." Journal of Family History (2006) 31(1): 28-44. Issn: 0363-1990 Fulltext: online in EBSCO

- ^ Michael A. McDonnell, "Class War: Class Struggles During the American Revolution in Virginia," William and Mary Quarterly 2006 63(2): 305–344. Issn: 0043-5597 Fulltext: online at History Cooperative

- ^ Higginbotham (1983), pp. 75–77

- ^ Stephenson (1925), pp. 271–281

- ^ * Elwin L. Page. "The King's Powder, 1774," New England Quarterly Vol. 18, No. 1 (Mar., 1945), pp. 83-92 in JSTOR

- ^ Arthur S. Lefkowitz, "The Long Retreat: The Calamitous American Defense of New Jersey 1776, 1998. Retrieved September 10, 2007.

- ^ Thomas A. Desjardin, Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775 (2006)

- ^ Willard Sterne Randall, "Benedict Arnold at Quebec," MHQ: Quarterly Journal of Military History, Summer 1990, Vol. 2 Issue 4, pp 38-49

- ^ Desjardin, Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775 (2006)

- ^ Watson (1960), p. 203.

- ^ Arthur S. Lefkowitz, Benedict Arnold's Army: The 1775 American Invasion of Canada during the Revolutionary War (2007)

- ^ Fischer (2004), pp. 51–52,83

- ^ Fischer (2004), p. 29

- ^ Fischer (2004), pp. 91–101

- ^ Fischer (2004), pp. 102–111

- ^ Stiles, Henry Reed. "Letters from the prisons and prison-ships of the revolution". Thomson Gale, December 31, 1969. ISBN 978-1-4328-1222-5

- ^ Dring, Thomas and Greene, Albert. "Recollections of the Jersey Prison Ship" (American Experience Series, No 8). Applewood Books. November 1, 1986. ISBN 978-0-918222-92-3

- ^ Lang, Patrick J. "The horrors of the English prison ships, 1776 to 1783, and the barbarous treatment of the American patriots imprisoned on them". Society of the Friendly Sons of Saint Patrick, 1939.

- ^ Onderdonk. Henry. "Revolutionary Incidents of Suffolk and Kings Counties; With an Account of the Battle of Long Island and the British Prisons and Prison-Ships at New York." Associated Faculty Press, Inc. June, 1970. ISBN 978-0-8046-8075-2.

- ^ West, Charles E. "Horrors of the prison ships: Dr. West's description of the wallabout floating dungeons, how captive patriots fared." Eagle Book Printing Department, 1895.

- ^ Fischer (2004), pp. 115–137

- ^ Fischer (2004), pp. 138–140

- ^ Fischer (2004), pp. 143–205

- ^ Fischer (2004), pp. 206–259

- ^ Fischer (2004), pp. 277–343

- ^ Fischer (2004), pp. 345–358

- ^ Ketchum (1997), p. 84

- ^ Ketchum (1997), pp. 285–323

- ^ Higginbotham (1983), pp. 188–98

- ^ Higginbotham (1983), pp. 175–188

- ^ Springfield Armory

- ^ Jonathan R. Dull, A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution (1987) ch 7-9

- ^ Trevelyan (1912), vol. 1, p. 4

- ^ Trevelyan (1912), vol. 1, p. 5

- ^ Privateers or Merchant Mariners help win the Revolutionary War

- ^ Privateers

- ^ Higginbotham (1983), pp. 331–46

- ^ Heintze, “A Chronology of Notable Fourth of July Celebration Occurrences”.

- ^ Riddick (2006), pp. 23–25

- ^ Fletcher (1909), pp. 155–158

- ^ Edler (1911), pp. 37–38, 42–62; The American trade via St. Eustatius was very substantial. In 1779 more than 12,000 hogsheads of tobacco and 1.5 million ounces of indigo were shipped from the Colonies to the island in exchange for naval supplies and other goods; Edler, p. 62

- ^ Edler (1911), pp. 95–173

- ^ Edler (1911), pp. 233–246

- ^ Edler (1911), pp. 205–232

- ^ Henry Lumpkin, From Savannah to Yorktown: The American Revolution in the South (2000)

- ^ John W. Gordon and John Keegan, South Carolina and the American Revolution: A Battlefield History (2007)

- ^ Hugh F. Rankin, North Carolina in the American Revolution (1996)

- ^ Lumpkin, From Savannah to Yorktown: The American Revolution in the South (2000)

- ^ Michael Cecere, Great Things are Expected from the Virginians: Virginia in the American Revolution (2009)

- ^ Colin Gordon Calloway, The American Revolution in Indian Country (1995)

- ^ Lowell Hayes Harrison, George Rogers Clark and the War in the West (2001)

- ^ Richard Ferrie, The World Turned Upside Down: George Washington and the Battle of Yorktown (1999)

- ^ Mackesy, p. 435.

- ^ Richard Morris, The Peacemakers: The Great Powers and American Independence (1983)

- ^ Benn (1993), p. 17

- ^ Lawrence S. Kaplan, "The Treaty of Paris, 1783: A Historiographical Challenge," International History Review, Sept 1983, Vol. 5 Issue 3, pp 431-442

- ^ Pole and Greene, eds. Companion to the American Revolution ch 36-39

- ^ Black (2001), p. 39; Greene and Pole (1999), pp. 298, 306

- ^ Higginbotham (1983), pp. 298, 306; Black (2001), pp. 29, 42

- ^ Black (2001), pp. 14–16 (Harsh methods), pp. 35, 38 (slaves and Indians), p. 16 (neutrals into revolutionaries)

- ^ Smallpox epidemic: Fenn, p. 275. A great number of these smallpox deaths occurred outside the theater of war—in Mexico or among Native Americans west of the Mississippi River. Washington and inoculation: Ellis, p. 87.

- ^ Edwin G. Burrows "Patriots or Terrorists?," American Heritage, Fall 2008.

- ^ American dead and wounded: Shy, pp. 249–50. The lower figure for number of wounded comes from Chambers, p. 849.

- ^ Mackesy (1964), pp. 6, 176 (British seamen)

- ^ Tombs (2007), p. 179

- ^ Jensen (2004), p. 379

References

- Black, Jeremy. War for America: The Fight for Independence, 1775–1783. 2001. Analysis from a noted British military historian.

- Benn, Carl. Historic Fort York, 1793–1993. Toronto: Dundurn Press Ltd., 1993. ISBN 0-920474-79-9.

- Boatner, Mark Mayo, III. Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. 1966; revised 1974. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1. Military topics, references many secondary sources.

- Chambers, John Whiteclay II, ed. in chief. The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-19-507198-0.

- Crocker III, H. W. (2006). Don't Tread on Me. New York: Crown Forum. ISBN 978-1-4000-5363-6.

- Duffy, Christopher. The Military Experience in the Age of Reason, 1715–1789 Routledge, 1987. ISBN 978-0-7102-1024-1.

- Edler, Friedrich. The Dutch Republic and The American Revolution. University Press of the Pacific, 1911, reprinted 2001. ISBN 0-89875-269-8.

- Ellis, Joseph J. His Excellency: George Washington. (2004). ISBN 1-4000-4031-0.

- Fenn, Elizabeth Anne. Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775–82. New York: Hill and Wang, 2001. ISBN 0-8090-7820-1.

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-19-517034-2.

- Fletcher, Charles Robert Leslie. An Introductory History of England: The Great European War, Volume 4. E.P. Dutton, 1909. OCLC 12063427.

- Greene, Jack P. and Pole, J.R., eds. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell, 1991; reprint 1999. ISBN 1-55786-547-7. Collection of essays focused on political and social history.

- Higginbotham, Don. The War of American Independence: Military Attitudes, Policies, and Practice, 1763–1789. Northeastern University Press, 1983. ISBN 0-930350-44-8. Overview of military topics; online in ACLS History E-book Project.

- Jensen, Merrill. The Founding of a Nation: A History of the American Revolution 1763–1776. (2004)

- Kaplan, Sidney and Emma Nogrady Kaplan. The Black Presence in the Era of the American Revolution. Amherst, Massachusetts: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1989. ISBN 0-87023-663-6.

- Ketchum, Richard M. Saratoga: Turning Point of America's Revolutionary War. Henry Holt, 1997. ISBN 0-8050-4681-X.

- Mackesy, Piers. The War for America: 1775–1783. London, 1964. Reprinted University of Nebraska Press, 1993. ISBN 0-8032-8192-7. Highly regarded examination of British strategy and leadership.

- McCullough, David. 1776. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005.

- Riddick, John F. The history of British India: a chronology. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006. ISBN 978-0-313-32280-8.

- Savas, Theodore P. and Dameron, J. David. A Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution. New York: Savas Beatie LLC, 2006. ISBN 1-932714-12-X.

- Schama, Simon. Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves, and the American Revolution, New York, NY: Ecco/HarperCollins, 2006

- Shy, John. A People Numerous and Armed: Reflections on the Military Struggle for American Independence. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976 (ISBN 0-19-502013-8); revised University of Michigan Press, 1990 (ISBN 0-472-06431-2). Collection of essays.

- Stephenson, Orlando W. "The Supply of Gunpowder in 1776", American Historical Review, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Jan. 1925), pp. 271–281 in JSTOR.

- Tombs, Robert and Isabelle. That Sweet Enemy: The French and the British from the Sun King to the Present Random House, 2007. ISBN 978-1-4000-4024-7.

- Trevelyan, George Otto. George the Third and Charles Fox: the concluding part of The American revolution Longmans, Green, 1912.

- Watson, J. Steven. The Reign of George III, 1760–1815. 1960. Standard history of British politics.

- Weigley, Russell F. The American Way of War. Indiana University Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0-253-28029-9.

- Weintraub, Stanley. Iron Tears: America's Battle for Freedom, Britain's Quagmire: 1775–1783. New York: Free Press, 2005 (a division of Simon and Schuster). ISBN 0-7432-2687-9. An account of the British politics on the conduct of the war.

Further reading

These are some of the standard works about the war in general which are not listed above; books about specific campaigns, battles, units, and individuals can be found in those articles.

- Bancroft, George. History of the United States of America, from the discovery of the American continent. (1854–78), vol. 7–10.

- Bobrick, Benson. Angel in the Whirlwind: The Triumph of the American Revolution. Penguin, 1998 (paperback reprint).

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, and Ryerson, Richard A., eds. The Encyclopedia of the American Revolutionary War: A Political, Social, and Military History (ABC-CLIO, 2006) 5 volume paper and online editions; 1000 entries by 150 experts, covering all topics

- Billias, George Athan. George Washington's Generals and Opponents: Their Exploits and Leadership (1994) scholarly studies of key generals on each side

- Hibbert, Christopher. Redcoats and Rebels: The American Revolution through British Eyes. New York: Norton, 1990. ISBN 0-393-02895-X.

- Kwasny, Mark V. Washington's Partisan War, 1775–1783. Kent, Ohio: 1996. ISBN 0-87338-546-2. Militia warfare.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789. Oxford University Press, 1984; revised 2005. ISBN 0-19-516247-1. online edition

- Symonds, Craig L. A Battlefield Atlas of the American Revolution (1989), newly drawn maps

- Ward, Christopher. The War of the Revolution. 2 volumes. New York: Macmillan, 1952. History of land battles in North America.

- Wood, W. J. Battles of the Revolutionary War, 1775–1781. ISBN 0-306-81329-7 (2003 paperback reprint). Analysis of tactics of a dozen battles, with emphasis on American military leadership.

- Men-at-Arms series: short (48pp), very well illustrated descriptions:

- Zlatich, Marko; Copeland, Peter. General Washington's Army (1): 1775–78 (1994)

- Zlatich, Marko. General Washington's Army (2): 1779–83 (1994)

- Chartrand, Rene. The French Army in the American War of Independence (1994)

- May, Robin. The British Army in North America 1775–1783 (1993)

- The Partisan in War, a treatise on light infantry tactics written by Colonel Andreas Emmerich in 1789.

External links

- Important People of the American Revolutionary War

- American Revolutionary War History Resources

- Spain's role in the American Revolution from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean

- African-American soldiers in the Revolution

- American Revolution & Independence

- Liberty – The American Revolution from PBS

- American Revolutionary War 1775–1783 in the News

- Haldimand Collection Haldimand Collection, 232 series fully indexed; extensive military correspondence of British generals

- Africans in America from PBS

- Approval of the American victory in England Unique arch inscription commemorates "Liberty in N America Triumphant MDCCLXXXIII"

- The Spanish and Latin American Contribution to the American Revolutionary War

- The American Revolution as a People’s War by William F. Marina, The Independent Institute, July 1, 1976

- Important battles of the American Revolutionary War

Bibliographies

- Library of Congress Guide to the American Revolution

- Bibliographies of the War of American Independence compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History

- Political bibliography from Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link GA Template:Link FA