Coil (band)

Coil | |

|---|---|

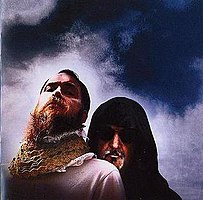

Coil (Left: John Balance, Right: Peter Christopherson) | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | Black Light District, ELpH, Sickness of Snakes, The Eskaton, Time Machines |

| Origin | London, England |

| Genres | Industrial, post-industrial, experimental, noise, electronic, electro-industrial, avant-garde, dark ambient, drone |

| Years active | 1982–2004 |

| Labels | Threshold House, Eskaton, Chalice, Solar Lodge |

| Past members | John Balance Peter Christopherson Jim Thirlwell Danny Hyde Stephen Thrower Drew McDowall William Breeze Thighpaulsandra Ossian Brown |

| Website | http://www.thresholdhouse.com/ |

Coil was an English cross-genre, experimental music group formed in 1982 by John Balance—later credited as "Jhonn Balance"—and his partner Peter Christopherson, aka "Sleazy".[1] The duo worked together on a series of releases before Balance chose the name Coil, which he claimed to be inspired by the omnipresence of the coil's shape in nature. Today, Coil remains one of the most influential and best known industrial music groups.

The group's first official release as Coil was a 1984 12" titled How to Destroy Angels released on the Belgian Les Disque de Crepuscule's sublabel LAYLAH Antirecords. Following the 12"s success, Coil produced a series of three albums, Scatology, Horse Rotorvator and Love's Secret Domain, which met with little commercial success, but were praised as innovative due to their blend of industrial music and acid house.[2][3]

In 1985, the group began working on a series of soundtracks, amongst them music for the first Hellraiser movie based on the novel The Hellbound Heart by their acquaintance at that time, Clive Barker. In 1999 the group gave their first live performance in sixteen years, and began a series of mini-tours which would last until 2004.[4] Following the death of John Balance on 13 November 2004, Peter Christopherson announced via their official record label website Threshold House that Coil as an entity had ceased to exist.

Beginning (1982–1984)

Coil was formed in 1982 following Christopherson's departure from Psychic TV.[1] Balance and Christopherson began working with John Gosling on the project Zos Kia, which resulted in four live performances and the 1984 cassette tape Transparent. Following Gosling's departure Balance and Christopherson teamed up with Boyd Rice, and under the alias Sickness of Snakes released the split album Nightmare Culture with the experimental group Current 93.

While working on their first official release, 1984's 12"How to Destroy Angels, the group settled on the name Coil. According to the sleeve notes, the single track LP is "ritual music for the accumulation of male sexual energy" and was produced under a variety of technological, spiritual, and meteorological conditions which the band felt to be magickally significant.

Since its initial release, Transparent has been reissued in CD format, while How to Destroy Angels has been remixed by Nurse with Wound's Steven Stapleton and released on a full length CD. Tracks from Nightmare Culture have featured on the group's Unnatural History compilation series.

Scatology, Horse Rotorvator, and Love's Secret Domain (1984–1992)

Following the underground hit How to Destroy Angels, Coil left L.A.Y.L.A.H. Antirecords for Some Bizzare and produced Scatology, released in 1984 as their first full length studio album. The album was largely based on the sound of industrial music as well as the Post-punk movement. While songs such as "Restless Day", "Panic" and "Tainted Love" are representative of a mainstream style, other tracks preview what would become Coil's unique electronic style. The single Panic/Tainted Love became the first AIDS benefit music release, as the profits from sales of the single were donated to the Terrence Higgins Trust.[5] The "Tainted Love" music video, directed by Peter Christopherson, is on permanent display at The Museum of Modern Art in New York.[6]

Horse Rotorvator followed in 1986 as the next full length release. Although songs such as "The Anal Staircase" and "Circles of Mania" sound like evolved versions of Scatology material, the album is characterized by slower tempos, and represented a new direction for the group. The album has a darker theme than previous releases; according to Balance, "Horse Rotorvator was this vision I'd had of this mechanical/flesh thing that ploughed up the earth and I really did have a vision of it—a real horrible, burning, dripping, jaw-like vision in the night...The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse killed their horses and use their jawbones to make this huge earth-moving machine."[7] The artwork features a photograph of the location of a notorious IRA bombing, in which a bomb was detonated on a military orchestra pavilion.[6] Horse Rotorvator was in part influenced by the AIDS related deaths of some of their friends.[8] Furthermore, the song "Ostia (The Death of Pasolini)", is about the mysterious death of Pier Paolo Pasolini as well as what Balance described as "the number one suicide spot in the world", the white cliffs of Dover.[9] After the release of Horse Rotorvator Coil left Some Bizarre Records, due to the record company's debt of GB£10,000 to the group.[10] Gold Is the Metal with the Broadest Shoulders followed as a full length release, marking the beginning of the label Threshold House; that album being described in the liner notes as "not the follow up to Horse Rotorvator but a completely separate package - a stopgap and a breathing space - the space between two twins," referring to Horse Rotorvator and Love's Secret Domain.

Love's Secret Domain (abbreviated LSD) followed in 1991 as the next "proper" Coil album, although a few minor releases had been produced since Horse Rotorvator. LSD represents a progression in Coil's style and became a template for what would be representative of newer waves of post-industrial music, blended with their own style of acid house. Although the album was more upbeat, it was not intended as a dance record, as Christopherson explained "I wouldn't say it's a party atmosphere, but it's more positive."[8][11] "Windowpane" and a Jack Dangers remix of "The Snow" were released as singles, both of which had music videos directed by Christopherson. The video for "Windowpane" was shot in the Golden Triangle, where, Balance claimed, "the original Thai and Burmese drug barons used to exchange opium for gold bars with the CIA."[8] Christopherson recalled "John [Balance] discovered while he was performing that where he was standing was quicksand! In the video you can actually see him getting deeper and deeper."[8] Furthermore, Thai friends of the group commented that they had known of several people that died where Coil had shot footage for the music video.[8] A music video for the song "Love's Secret Domain" was also shot and is currently unreleased and unaired due to its nature: as Christopherson explained, "We shot 'Love's Secret Domain' in a go-go boy bar in Bangkok; with John [Balance] performing on stage with about 20 or 30 dancing boys, which probably won't get played on MTV, in fact!"[8] Stolen & Contaminated Songs followed as a full length release. However, as with Gold Is the Metal..., it is a collection of outtakes and demos from the LSD era.

Soundtracks and side projects (1993–1998)

Coil separated their works into many side projects, publishing music under different names and a variety of styles. The pre-Coil aliases, Zos Kia and Sickness of Snakes, formed the foundation of a style that would evolve to characterize their initial wave of releases.

Before embarking on their second wave of side projects and pseudonyms, Coil created a soundtrack for the movie Hellraiser, although they withdrew from the project when they suspected their music would not be used.[12] Furthermore, Coil claimed inspiration for Pinhead was partly drawn from the piercing magazines director Clive Barker borrowed from the group.[12] Beginning in 1993, Coil contributed music to two of Derek Jarman's films, Blue and The Angelic Conversation. In addition, they recorded soundtracks for the documentary Gay Man's Guide to Safer Sex as well as Sarah Dales Sensuous Massage, though both remain unreleased.[12]

Much like the pre-Coil aliases, Coil's wave of side projects represent a sort of primordial soup from which the group evolved a different style of sound. While Nasa Arab—credited to the group's project "The Eskaton"—was Coil's farewell to the acid house genre, the following projects, ELpH, Black Light District, and Time Machines, were all based heavily on experimentation with drone, an ingredient which would define Coil's following work. These releases also kicked off the start of Coil's new label Eskaton.

Late Coil (1998–2004)

After the wave of experimental side projects, Coil's sound was completely redefined. Before releasing new material, the group released the compilations Unnatural History II, Windowpane & The Snow and Unnatural History III. In March 1998, Coil began to release a series of four singles which were timed to coincide with the equinox and solstices of that year. The singles are characterized by slow, drone-like instrumental rhythms, and electronic or orchestral instrumentation.[13] The first single, Spring Equinox: Moon's Milk or Under an Unquiet Skull, featured two versions of the same song, the second version of which included an electric viola contribution from a newly inducted member, William Breeze. The second single, Summer Solstice: Bee Stings, also featured performances by Breeze, and also included the industrial-noise song "A Warning from the Sun (For Fritz)", which was dedicated to a friend of Balance and Christopherson's who had committed suicide earlier that year.[14] The third single, Autumn Equinox: Amethyst Deceivers includes the track "Rosa Decidua" which features vocals by Rose McDowall. The single also features the song "Amethyst Deceivers", later reworked and performed throughout most of Coil's tour, and eventually re-made into an alternate version on the LP The Ape of Naples. The fourth single, Winter Solstice: North, also includes a track sung by Rose McDowall, and is partially credited to the side project Rosa Mundi. The series would later be re-released as the double-CD set Moon's Milk (In Four Phases).

Astral Disaster was created with the assistance from new band member Thighpaulsandra and released in January 1999 via Sun Dial member Gary Ramon's label Prescription.[15] Although the album was initially limited to just 99 copies, it would later be re-released in substantially different form. Musick To Play In The Dark Vol. 1 followed in September 1999 and a few months later Coil performed their first concert in 16 years. Queens Of The Circulating Library followed in April 2000, with production credit given to Thighpaulsandra. The single track, full length drone album is the only Coil release without the assistance of Christopherson. Musick To Play In The Dark Vol. 2 followed in September 2000 and Coil began to perform live heavily, writing the music for Black Antlers in between a series of mini-tours.[16] Coil also released a series of live albums around this time. Constant Shallowness Leads To Evil, a noise-driven experimental album reminiscent of Christopherson's work with Throbbing Gristle, was first sold at a live performance in September 2000. Coil finally released Black Antlers in June 2004.

In contrast to many of their earlier releases, Coil's later material is characterized by a slower sound which relies more on drone than acid house. This change in sound was reflected in their live performances, as songs like "Ostia" and "Slur" were slowed down from their original pace as well as re-recordings of "Teenage Lightning" and "Amethyst Deceivers" which were later released on The Ape Of Naples.[17]

Coil Live

Coil's live incarnation has a distinct legacy of its own. The first live shows took place in 1983, but after only four performances, fifteen years would pass before they would play live again.[4]

Coil performed twice at the Royal Festival Hall in 1998 (as part of a weekend curated by Julian Cope) when they first performed as the full band line-up - and the first time for the "fluffy suits" - the show was called 'Time Machines' at that point - then again in 2000 as part of the "Outro" week I curated for my departure from the South Bank - that time sharing a bill with Jim Thirlwell (as Foetus). Both performances were full sets.

On 14 December 1999 Coil performed elph.zwölf at Volksbuehne in Berlin. Although the performance lasted just under eighteen minutes, it marked the beginning of a new era of live performances. Coil would go on to perform close to fifty additional concerts, with varied set lists as well as performers.

Coil's performances were surrealistic visually and audibly. Balance, Christopherson, Thighpaulsandra and Ossian Brown were known to dress in fluffy suits; an idea inspired by Sun Ra.[18] The suits would later be used as album covers for the release Live One; other costumes appear on the covers of Live Two and Live Three (straitjacket and mirror-chested hooded jumpsuit respectively). Video screens projected footage and animations created by Christopherson, while fog machines created a thick eerie atmosphere. Balance would often screech and howl during performances, which would add to the effect.

John Balance's problem with alcohol would often reflect the way in which the Coil performances were carried out. His drinking problem became so well known that during the 2003 All Tomorrow's Parties performance a fan asked if there is any "blood in his alcohol", a reference to the Coil song "Heartworms". Balance replied that there is no "alcohol in my blood at the moment", later adding "I've got horse tranquillizer for later". The performance, including the dialogue, was released on ...And The Ambulance Died In His Arms.

Many Coil performances were released, including the widely available releases of Live Four, Live Three, Live Two, Live One and ...And The Ambulance Died In His Arms, as well as several very limited editions such as Selvaggina, Go Back Into The Woods and Megalithomania!. Video recordings of several concerts were released on the DVD box set Colour Sound Oblivion in 2010.[19]

Coil's final performance was at DEAF (Dublin Electronic Arts Festival), Dublin City Hall in Ireland.

Deaths of John Balance & Peter Christopherson

John Balance died on 13 November 2004 after having fallen from a second floor landing in his home. Peter Christopherson announced Balance's death on the Threshold House website and provided details surrounding the tragedy. Balance's memorial service was held near Bristol on November 23 and was attended by approximately 100 people.[20] On 25 November 2004 Christopherson announced he was in agreement with Balance's partner, Ian Johnstone, that any releases, either as Coil or solo work that Balance was working on at the time of his death, would be put on hold. They decided that time was needed to mourn Balance's passing, recuperate from the loss, and assess the quality of the unreleased work. It was also decided that existing video, audio and other works that were in various states of completion at the time of Balance's death would eventually be released under the name Coil, and all other planned appearances and releases would be canceled. The already-planned live album ...And The Ambulance Died In His Arms was released in April 2005, the name having been chosen by Balance before his death.

Several tribute albums were released in memory of Balance including the compilations Full Cold Moon, The Loneliest Link In A Very Strange Chain (which had been started before Balance passed and was originally due to be called "Never", but switched titles after the tragic event), Coilectif: In memory ov John Balance and homage to Coil, ...It Just Is and X-Rated: The Dark Files. The album How He Loved The Moon (Moonsongs For Jhonn Balance) by Balance collaborator David Tibet was released under his group Current 93. A live album by Throbbing Gristle was also dedicated to Balance. On 23 December 2005, a memorial concert was held for Balance. Performers included Christopherson's new solo effort The Threshold HouseBoy's Choir, Alec Empire and CoH.

The final studio album, The Ape of Naples, saw release on 2 December 2005. In August 2006 the rare CD-R releases The Remote Viewer and Black Antlers were "sympathetically remastered" and expanded into two disc versions, which included new and recently remixed material. A comprehensive 16-DVD boxset, titled Colour Sound Oblivion was released in July 2010. A "Patron Edition" was pre-orderable in November 2009 and was sold out in three hours. Christopherson had also discussed the possibility of releasing Coil's entire back catalogue on a single Blu-ray disc.[21]

In November 2006, the official Coil website posted the following announcement: "Following the success of Thai pressings of The Remote Viewer and Black Antlers, and after many requests, we are planning to expand the CD catalog still further." A few days later Duplais Balance and Moon's Milk In Six Phases were announced.[22] Furthermore, an expanded vinyl version of The Ape Of Naples, which includes the album The New Backwards has been released and a two disc version of Time Machines has been announced.[22]

Six years after the death of John Balance, Peter Christopherson died in his sleep on November 24, 2010.[23]

Background

Limited editions

Coil's distribution and marketing techniques sometimes included releasing a limited number of albums making them collectors' items among devotees.[24] Including things such as "art objects", blood stains and sigil-like autographs in the packaging of their albums, Coil claimed that this made their work more personal for true fans, turning their records into something akin to occult artifacts.[9] This practice was markedly increased in the later half of Coil's career. However, Balance expressed interest in having regular Coil albums in every shop that wanted them.[9] Some critics have accused Coil and its record company of price gouging.[25] In 2003, Coil began re-releasing many rare works, mostly remixed, into general circulation.[22] They also launched a download service, where a large amount of their out-of-print music is available.

Instruments and creative methods

Coil incorporated many exotic and rare instruments into their recordings and performances. The group expressed particular interest in modular synthesizers, including the Moog synthesizer.[26][27] Coil are among the few artists who have been granted permission to use the one-of-a-kind experimental ANS photoelectronic synthesizer (see ANS). Other instruments the group incorporated into their music included the theremin and electronic shakuhachi. During Coil's later period, marimba player Tom Edwards joined the group and performed on the live albums Live Two and Live Three, as well as on the studio album The Ape of Naples.

Coil utilized techniques such as the cut-up technique, ritual drug use, sleep deprivation, lucid dreaming, sidereal sound, granular synthesis, tidal shifts, John Dee-like methods of scrying, instrument glitches, SETI synchronization and the chaos theory.[7][8][11][21][28][29]

Religious views

Coil had many associations with Pagan beliefs and were sometimes labeled satanic.[29][30] John Balance explicitly referred to himself as a "Born Again Pagan" and described his Paganism as a "spirituality within nature."[18]

Peter Christopherson, however, described the beliefs of Coil as unassociated: "We don't follow any particular religious dogma. In fact, quite the reverse, we tend to discourage the following of dogmas, or false prophets, as it were. And we don't have a very sympathetic view of Christians up to this point. The thing we follow is our own noses; I don't mean in a chemical sense."[8]

Members and style

Coil's worked in such genres as industrial, noise, ambient and dark ambient, neo-folk, spoken word, drone music, and minimalism, creating what Balance explicitly referred to as "magickal music".[9] Balance described the early Coil work as "solar" and the later work as "moon musick".[9]

John Balance was the founder of Coil and was the primary vocalist and composer of Coil's music. Peter Christopherson was the chief producer. William Breeze was Coil's electric viola player between 1997 and 2000.[31] Ossian Brown had been a Coil collaborator since about 1992 and joined the group in 2000, touring extensively with them and working on several recordings up until the final Coil album The Ape Of Naples. Tom Edwards participated in Coil's live incarnation, and was Coil's marimba player from 2000 on.[32] John Gosling performed with the initial live incarnation of Coil and on Transparent. Danny Hyde has been a Coil collaborator since the beginning and throughout most of the group's career. His contributions include production and co-writing some material. Massimo & Pierce of Black Sun Productions were members of Coil Live in 2002. However, they were stage performers, never contributing musically other than reading the poetic introduction to "Ostia" during live performances.[27] Drew McDowall began collaborating with Coil in 1990 and was officially inducted in 1995. He left the group sometime between 1999 and 2000. Drew's ex-wife, Rose McDowall, provided vocals for several Coil tracks including "Wrong Eye", "Rosa Decidua" and "Christmas Is Now Drawing Near". She also collaborated with Coil for the short lived project Rosa Mundi. Cliff Stapleton played Hurdy Gurdy on several live performances, but also in the studio for Coil at various points throughout the 2000s. Thighpaulsandra became an official member on 26 January 1999 and participated until the final album, The Ape Of Naples. Most notably, he created the entire instrumental for the album Queens Of The Circulating Library.[33][34] Jim Thirlwell was a member during the Scatology era.[28] Stephen Thrower worked as a full time member of Coil from 1987 to 1992. Mike York was part of the Coil Live collective for a limited time.

Influence

Although Coil expressed interest in many musical groups, they rarely, if ever, claimed to be influenced by them. Coil explicitly stated the influence of such non-musical sources as William Burroughs, Aleister Crowley, Bryon Gysin and Austin Spare.[9] Furthermore, the group were friends with Burroughs and owned some of Spare's original artwork.[27]

John Balance encouraged fans to trade, discuss and discover new and different forms of music, stressing the importance of variety. Music that Coil expressed interest in is diverse and wide-ranging, from musique concrète to folk music to hardcore punk to classical. Among the musicians Coil expressed interest in were early electronic, experimental and minimalistic artists: Harry Partch, La Monte Young, Karlheinz Stockhausen (once referred to by Balance as "an honorary member of Coil"), Alvin Lucier, and Arvo Pärt.[26][35][36] Coil also expressed interest in krautrock groups including Cluster, Amon Düül II, Can, Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream. Rock musicians and groups Coil have expressed interest in are: Angus Maclise, Captain Beefheart, Flipper, Leonard Cohen, Lou Reed, Nico, Pere Ubu, The Birthday Party, The Velvet Underground and The Virgin Prunes.[9][18][26][35][36][37] Coil expressed an interest in the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, and in 1986 used a sample of a piece of his music on the Horse Rotorvator song "The Anal Staircase". Furthermore, on the album Black Antlers Coil dedicated a song to Sun Ra and covered a song by Bam Bam.[38]

Coil's influence on electronic music has become more evident since the death of Balance with electronic musicians from all over the world collaborating on a series of tribute albums. Some notable artists who appeared on these albums are Alec Empire, Chris Connelly and K.K. Null (see ...It Just Is). Nine Inch Nails front man Trent Reznor has also expressed his influence by the group.[39] The track "At The Heart Of It All" (found on Scatology) later became the name of an Aphex Twin track on Nine Inch Nails remix album Further Down the Spiral. It is possible that Trent Reznor named the track as a reference to Coil, since Coil also provided remixes for Further Down the Spiral. Furthermore, in 2010, Reznor, Mariqueen Maandig and Atticus Ross started a new band called How To Destroy Angels, the same title as Coil's first single.

Discography

Coil's rapid musical output over two decades resulted in a large amount of releases, side projects and remixes as well as collaborations.

Primary, full-length, Coil studio albums:

- Scatology (1984)

- Horse Rotorvator (1986)

- Love's Secret Domain (1991)

- ELpH vs. Coil: Worship the Glitch (1995)

- Black Light District: A Thousand Lights in a Darkened Room (1996)

- Time Machines (1998)

- Astral Disaster (1999)

- Musick to Play in the Dark Vol. 1 (1999)

- Musick to Play in the Dark Vol. 2 (2000)

- Constant Shallowness Leads to Evil (2000)

- The Ape of Naples (2005)

- Black Antlers (2006)

- The New Backwards (2008)

References

- ^ a b "Coil Interview: The Price of Existence is Eternal Warfare". AbrAhAdAbrA. No. 1. January 23, 1985. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ^ "Coil: Scatology, Horse Rotorvator, Love's Secret Domain". Liar Society (2004-10-30). Archived from the original on 6 February 2008. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Kopf, Biba (April 20, 1985). "The Soil And Spoil Tactics Of Coil". NME.

- ^ a b "Live Archive". brainwashed.com (2004). Retrieved 2007-02-12.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Boys From The Crap Stuff". Zigzag Magazine (September 1985). Archived from the original on 2005-03-04. Retrieved 2007-09-15.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "Lust's Dark Exit". Electric Dark Space. 1991. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ^ a b Keenan, David (September 1998). "Time Out Of Joint". The Wire. Retrieved April 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sonn, Marlena (June 1991). "Entering A More Pleasant Domain". Alternative Press. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Coil ((2001 June 20)). "Radio Inferno, Dutch Radio4 Supplement" (Interview). Retrieved 2009-07-26.

{{cite interview}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|subjectlink3=,|subjectlink2=,|city=,|program=,|month=,|cointerviewers=, and|subjectlink=(help); More than one of|subject=and|last=specified (help); Unknown parameter|callsign=ignored (help) - ^ Neal, Charles (1987). "Tape Delay". Tape Delay. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ a b "La Stampa". VPRO (1991 April 17). Retrieved 2007-01-06.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c Dickie, Tony. "Compulsion". brainwashed.com, Winter 1992. Retrieved on 23 February 2007. Cite error: The named reference "Compulsion, Number 1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Moons Milk". Brainwashed.com. Archived from the original on 30 January 2008. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Coil News 1998". Brainwashed.com (1998). Retrieved 2007-01-04.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Astral Disaster". Brainwashed.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Black Antlers". Brainwashed.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "The Ape Of Naples". Brainwashed.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2008. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c Coil (October 22, 2004). "Rattlebag ([[RTÉ Radio 1]])" (Interview). Interviewed by Dungan, Myles. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

{{cite interview}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|subjectlink3=,|subjectlink2=,|program=,|callsign=,|cointerviewers=, and|subjectlink=(help); More than one of|subject=and|last=specified (help); URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - ^ "NEWS". brainwashed.com (2006). Archived from the original on 31 January 2008. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Christopherson, Peter (2005). "Who'll Fall?". Threshold House. Retrieved 2007-03-02.

- ^ a b Regnaert, Grant; Ferguson, Paul (August 26, 2006). "Coil: The Million Dollar Altar". Brainwashed.com. Retrieved 2009-07-26. Cite error: The named reference "Coil: The Million Dollar Altar" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Christopherson, Peter (2006). "Arrivals". Threshold House. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ Coil-Bandwebsite

- ^ "Coil News 2000". Brainwashed.com (2000). Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "The Wheel". Brainwashed.com. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-01.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c Whitney, Jon (May 5, 1997). "The Complete Interview". Brainwashed.com. Retrieved 2009-07-26. Cite error: The named reference "The Complete Interview" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c "Mutek". (2003 May 15). Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ^ a b Lewis, Scott (May 1992). "Coil's Agony and Ecstasy". Option. Retrieved 2009-07-26. Cite error: The named reference "Option, No. 44" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "UnCoiled". Mondo 2000. Retrieved 2009-07-26. Cite error: The named reference "Mondo 2000" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Pilkington, Mark. "Sounds Of Blakeness[dead link]". Fortean Times, (2001). Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- ^ "Coil News 1997". Brainwashed.com (1997). Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Supersonic". (unknown radio station) (2003 July 12). Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- ^ "Light Shining Darkly: A Coil Discography". Brainwashed.com (2005-01-01). Archived from the original on 16 January 2008. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Coil News 1999". Brainwashed.com (1999). Retrieved 2006-12-23.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b McKeating, Scott (April 12, 2004). "Sleazy: The Sylus Interview Series". Stylus. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ a b Moore, Dorian. "Coil: Beyond The Eskaton". Convulsion. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ "The Price Of Existence Is Eternal Warfare". Grok. November 1983. Archived from the original on 2006-07-10. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ "Stator Magazine". Stator Magazine (1987). Retrieved 2006-12-27.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Nine Inch Nails". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 12, 2007.

Influences[:] Skinny Puppy[,] Foetus[,] Coil[,] Ministry

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help)

See also

External links

- Official

- Threshold House - The official Coil website.

- Brainwashed.com/coil - Archival website

- Interviews

- COIL Interview Collection

- Brainwashed interview collection

- The Wire interview with Coil. (1998 July 21)

- Heathen Harvest Interview with Coil (2004 April 1)

- Stylus interview with Peter Christopherson. (2004 April 12)

- Coil: The Million Dollar Altar interview with Peter Christopherson (2006 August 29)

- Heathen Harvest Interview with Peter Christopherson (2006 September 1)

- British industrial music groups

- English electronic musicians

- British electronic music groups

- British experimental musical groups

- Musical groups established in 1982

- Musical groups from London

- Ableton Live users

- Musical groups disestablished in 2004

- Coil (band)

- LGBT-themed musical groups

- Dark ambient music groups