Prizren

Prizren | |

|---|---|

Municipality and city | |

| Prizren Prizren / Prizreni / Призрен | |

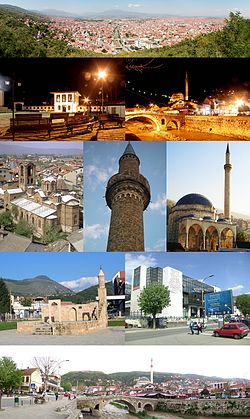

Top row: Prizren Second row: League of Prizren, Old Stone Bridge, Prizren Third row: Our Lady of Ljeviš, Minaret of Arasta Mosque, Sinan Pasha Mosque Forth row: Namazgâh, Municipality Building Bottom row: Prizrenska Bistrica | |

| Country | Kosovo[a] |

| District | District of Prizren |

| Area | |

| • Total | 640 km2 (250 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 402 m (1,319 ft) |

| Population (2012) | |

| • Total | 178,112 |

| • Density | 295.70/km2 (765.9/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 20000 |

| Area code | +381 29 |

| Car plates | 04 |

| Website | Municipality of Prizren |

Prizren (Template:Lang-sq or Prizreni; Template:Lang-bs; Template:Lang-sr, pronounced [prîzrɛn]; Template:Lang-tr) is a historic city located in Kosovo.[a] It is the administrative center of the eponymous municipality and district. The city has a population of around 178,000 (2011 census preliminary results),[1] mostly Albanians. Prizren is located on the slopes of the Šar Mountains (Template:Lang-sq) in the southern part of Kosovo. The municipality has a border with Albania and the Republic of Macedonia.

History

Ancient

The Roman[2] town of Theranda in Ptolemy's Geography is mentioned in the 2nd century AD. In the 5th century, it is mentioned as being restored in Dardania with the name of Petrizên by Procopius of Caesarea in De aedificiis (Book IV, Chapter 4).[3] Sometimes it is mentioned even in relation to the Justiniana Prima.[citation needed] It is thought that its modern name comes from old Serbian Призрѣнь, from при-зрѣти, indicating fortress which could be seen from afar[4] (compare with Czech Přízřenice or mount Ozren).

Medieval

Konstantin Jireček through the use of the correspondence of Demetrios Chomatenos, bishop of Ohrid concluded that Prizren was one of the areas of Albanian settlement in the era prior to the Slavic migrations/expansions.[5]

Bulgarian rulers controlled the Prizren area from the 850s, and Slav migrants arriving in the area were influenced by the Bulgarian orthodox church; Prizren had a bishopric subordinate to the archbishop in Ohrid. Bulgarian rule was replaced by Byzantine rule in the early eleventh century.[6]

In 1180-90, the Serbian prince Stefan Nemanja conquered "the district of Prizren".[7] this may refer to the Prizren diocese rather than the city itself, and he lost later control of these areas.[8] Stefan regained control of Prizren some time between 1208 and 1216. In 1220, the Byzantine Greek Orthodox bishop of the city was expelled as the Serbian rulers tried to impose their own ecclesiastical jurisdiction.[7] In the next centuries before the Ottoman conquest the city would pass to the Mrnjavčević, Balsić and Dukagjini families.

The Catholic church retained some influence in the area; 14th-century documents refer to a catholic church in Prizren, which was the seat of a bishopric between the 1330s and 1380s. Catholic parishes supported Ragusan merchants and Saxon miners.[9] Contemporary land-grants by the Serb monarchy refer to Vlach and Albanian populations, both peasants and noblemen, in the area around Prizren.

Ottoman

After several years of attack and counterattack, the Ottomans made a major invasion of Kosovo in 1454; Đurađ Branković retreated to the north and asked for help from John Hunyadi. On 21 June 1455, Prizren surrendered to the Ottoman army.Malcolm, N (1999). Kosovo: A Short History. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-06-097775-7.</ref> Prizren was the capital of the Sanjak of Prizren, and under new administrative organization of Ottoman Empire it became capital of the Vilayet.[10] This included the city of Tetova.[11] That time this open mosque had built. It is the first work of Ottoman architecture in Prizren.[citation needed] In recent years, has undergone serious repair and renovation.[citation needed]. Later it became a part of the Ottoman province of Rumelia. It was a prosperous trade city, benefiting from its position on the north-south and east-west trade routes across the Empire. Prizren became one of the larger cities of the Ottomans' Kosovo Province (vilayet). Prizren was the cultural and intellectual centre of Ottoman Kosovo. It was dominated by its Muslim population, who composed over 70% of its population in 1857. The city became the biggest Albanian cultural centre and the coordination political and cultural capital of the Kosovar Albanians. In 1871, a long Serbian seminary was opened in Prizren, discussing the possible joining of the old Serbia's territories with the Principality of Serbia.

Prizren was an important part of Kosovo Vilayet between 1877–1912.

During the late 19th century the city became a focal point for Albanian nationalism and saw the creation in 1878 of the League of Prizren, a movement formed to seek the national unification and liberation of Albanians within the Ottoman Empire.

The Young Turk Revolution was a step in the dissolving of the Ottoman empire that led to the Balkan Wars. The Third Army (Ottoman Empire) had a division in Prizren, at the time called Pirzerin, the 30th Pirzerin Reserve Infantry Division (Otuzuncu Pirzerin Redif Fırkası).

Modern

The Prizren attachment was part of the İpek Detachment in the Order of Battle, October 19, 1912 in the First Balkan War.

During the First Balkan War the city was seized by the Serbian army and incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbia[citation needed]. Although the troops met little resistance, the takeover was bloody. The British traveler Edith Durham attempted to visit it shortly afterwards but was barred by the authorities, as were most other foreigners, for the Montenegrin forces temporarily closed the city before full control was restored. The number of killed Albanians reached 400 to 4000. A few visitors did make it through—including Leon Trotsky, then working as a journalist—and reports eventually emerged of widespread killings of Albanians.[12]

After the First Balkan War of 1912, the Conference of Ambassadors in London allowed the creation of the state of Albania and handed Kosovo to the Kingdom of Serbia, even though the population of Kosovo remained mostly Albanian.[13]

With the invasion of the Kingdom of Serbia by Austro-Hungarian forces in 1915 during the First World War, the city was occupied by the Central Powers. The Serbian Army pushed the Central Powers out of the city in October 1918. By the end of 1918, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was formed. The Kingdom was renamed in 1929 to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Prizren became a part of its Vardar Banovina.

World War II

The Axis Italian forces conquered the city in 1941 during World War II; it was annexed to the Italian puppet state of Albania. In 1943 with the help of the German Wehrmacht Bedri Pejani created the Second League of Prizren.[14]

Federal Yugoslavia

In 1944, German forces were driven out of Kosovo by a combined Russian-Bulgarian force, and then the Communist government of Yugoslavia took control.[15] It was formulated as a part of Kosovo and Metohija, under Democratic Serbia as a part of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia. The Constitution defined the Autonomous Region of Kosovo and Metohija within the People's Republic of Serbia, a constituent state of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia.

The Province was renamed to Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo in 1974, remaining part of the Socialist Republic of Serbia, but having attributions similar to a Socialist Republic within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The former status was restored in 1989, and officially in 1990.

For many years after the restoration of Serbian rule, Prizren and the region of Dečani to the west remained centres of Albanian nationalism. In 1956 the Yugoslav secret police put on trial in Prizren nine Kosovo Albanians accused of having been infiltrated into the country by the (hostile) Communist Albanian regime of Enver Hoxha. The "Prizren trial" became something of a cause célèbre after it emerged that a number of leading Yugoslav Communists had allegedly had contacts with the accused. The nine accused were all convicted and sentenced to long prison sentences, but were released and declared innocent in 1968 with Kosovo's assembly declaring that the trial had been "staged and mendacious."

Kosovo War

The town of Prizren did not suffer much during the Kosovo War but its surrounding municipality was badly affected 1998–1999. Before the war, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe estimated that the municipality's population was about 78% Kosovo Albanian, 5% Serb and 17% from other national communities. During the war most of the Albanian population were either forced or intimidated into leaving the town. Tusus Neighborhood suffered the most. Some twenty-seven to thirty-four people were killed and over one hundred houses were burned.[16]

At the end of the war in June 1999, most of the Albanian population returned to Prizren. Serbian and Roma minorities fled, with the OSCE estimating that 97% of Serbs and 60% of Romas had left Prizren by October. The community is now predominantly ethnically Albanian, but other minorities such as Turkish, Ashkali (a minority declaring itself as Albanian Roma) and Bosniak (including Torbesh community) live there as well, be that in the city itself, or in villages around. Such locations include Sredska, Mamuša, the region of Gora, etc. [1]

The war and its aftermath caused only a moderate amount of damage to the city compared to other cities in Kosovo.[17] Serbian forces destroyed an important Albanian cultural monument in Prizren, the League of Prizren building[18][19] On March 17, 2004, during the Unrest in Kosovo, all Serb cultural monuments in Prizren were damaged, burned or destroyed, such as old Orthodox Serb churches:

- Our Lady of Ljeviš from 1307 (UNESCO World Heritage Site)[20]

- the Church of Holy Salvation[20]

- Church of St. George[20] (the city's largest church)

- Church of St. George[20] (Runjevac)

- Church of St. Kyriaki, Church of St. Nicolas (Tutić Church)[20]

- the Monastery of The Holy Archangels,[20] as well as

- Prizren's Ortodox seminary of Saint Cyrillus and Methodius[20]

Also, during that riot, entire Serb quarter of Prizren, near the Prizren Fortress, was completely destroyed, and all remaining Serb population was evicted from Prizren.[21][22]

21st century

The municipality of Prizren is still the most culturally and ethnically heterogeneous of Kosovo, retaining communities of Bosniaks, Turks, and Roma in addition to the majority Kosovo Albanian population live in Prizren. Only a small number of Kosovo Serbs remains in Prizren and area, residing in small villages, enclaves, or protected housing complexes.[2] Furthermore, Prizren's Turkish community is socially prominent and influential, and the Turkish language is widely spoken even by non-ethnic Turks.

Official languages

In Prizren Municipality, Albanian, Serbian, Bosnian and Turkish languages are official languages.[23][24]

Culture

Prizren is the seat of a summer documentary film festival called Dokufest. The city is home to numerous mosques, Orthodox and Catholic churches and other monuments. Among them:

- Saint Archangels Monastery

- League of Prizren Monument

- Kaljaja fortress

- Church of Holy Salvation

- Our Lady of Ljeviš church

- Church of St. Nicholas

- Sinan Pasha Mosque

- Church of St. Kyriaki

- The Mosque of Muderis Ali Efendi

- The St. George Cathedral

- Mosque Katip Sinan Qelebi

- Cathedral of Our Lady of Perpetual Succour

- The Lorenc Antoni Music school

These monuments, part of the historic center of the city, have recently been threatened by development pressures.[25] In addition, war, fires, general dilapidation and neglect have taken their toll on this unique architectural landscape.[26]

| Name | Description | Picture |

|---|---|---|

| The Shadervan Template:Lang-tr is a tourist area on the south side of town, there are numerous cafes and restaurants there. The ancient water fountain is a protected cultural monument, there is a legend that if you drink from it you will be sure to come back.[27][28][29] |

| |

| The Old Stone Bridge (Template:Lang-sq, Template:Lang-sr) is one of the landmarks of Prizren. It crosses the Prizrenska Bistrica. |

| |

| The Tannery/Leatherworks in Prizren (Template:Lang-sq, Template:Lang-sr )[30] is an ancient handcraft building. Tabakëve is the Albanian, and табахана the Serbian version, both from Template:Lang-tr, where -ana means house.[31] | ||

| The old Turkish bath (Template:Lang-sr) is in the center of Prizren. |

| |

| 1534 (1543?) Mosque of Kuklibeu Template:Lang-sq also known as Kukli Bej Mosque |

| |

| Mosque of Mustafe Pashe Prizrenit (Xhamia e Mustafë Pashë Prizrenit/Xhamia e Mustafa Pashës). 1562–1563 Destroyed in 1950 after a storm. It was located at the location of the former UNMIK headquarters, now municipality building 42°12′36″N 20°44′11″E / 42.210060°N 20.736372°E |

| |

| 1543–1581 Mosque of Muderis Ali Efendi |

| |

| The Sinan Pasha Mosque (Template:Lang-sq, Template:Lang-sr, Template:Lang-tr) is an Ottoman mosque in the city of Prizren, Kosovo.[a] It was built in 1615 by Sofi Sinan Pasha, bey of Budim.[32] The mosque overlooks the main street of Prizren and is a dominant feature in the town's skyline.[33] |

| |

Minaret of Arasta Mosque |

The remaining minaret of the Arasta Mosque |

|

Economy

For a long time the economy of Kosovo was based on retail industry fueled by remittance income coming from a large number of immigrant communities in Western Europe. Private enterprise, mostly small business, is slowly emerging food processing. Private businesses, like elsewhere in Kosovo, predominantly face difficulties because of lack of structural capacity to grow. Education is poor, financial institutions basic, regulatory institutions lack experience. Central and local legislatures do not have an understanding of their role in creating legal environment good for economic growth and instead compete in patriotic rhetoric. Securing capital investment from foreign entities cannot emerge in such an environment. Due to financial hardships, several companies and factories have closed and others are reducing personnel. This general economic downturn contributes directly to the growing rate of unemployment and poverty, making the financial/economic viability in the region more tenuous.[34]

Many restaurants, private retail stores, and service-related businesses operate out of small shops. Larger grocery and department stores have recently opened. In town, there are eight sizeable markets, including three produce markets, one car market, one cattle market, and three personal/hygienic and house wares markets. There is an abundance of kiosks selling small goods. Prizren appears to be teeming with economic prosperity, but appearances are deceiving as the international presence is reduced and repatriation of refugees and internally displaced persons is expected to further strain the local economy. Market saturation, high unemployment, and a reduction of financial remittances from abroad are ominous economic indicators.[34]

There are three agricultural co-operatives in three villages. Most livestock breeding and agricultural production is private, informal, and small-scale. There are five operational banks with branches in Prizren, the Micro Enterprise Bank (MEB), the Raiffeisen Bank, the Nlb Bank, the Teb Bank and the Payment and Banking Authority of Kosovo (BPK).[34]

Climate

| Climate data for Prizren | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.2 (68.4) |

22.4 (72.3) |

26.0 (78.8) |

31.3 (88.3) |

33.8 (92.8) |

40.6 (105.1) |

40.8 (105.4) |

37.3 (99.1) |

35.8 (96.4) |

31.4 (88.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

40.8 (105.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.9 (53.4) |

17.2 (63.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.3 (82.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

11.1 (52.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

16.9 (62.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

7.1 (44.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

1.8 (35.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.0 (26.6) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

2.7 (36.9) |

6.9 (44.4) |

11.3 (52.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

7.3 (45.1) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

7.1 (44.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −23.6 (−10.5) |

−19.1 (−2.4) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.3 (45.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−17.4 (0.7) |

−23.6 (−10.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 76.2 (3.00) |

54.1 (2.13) |

63.5 (2.50) |

61.1 (2.41) |

66.7 (2.63) |

69.7 (2.74) |

58.6 (2.31) |

127.4 (5.02) |

58.2 (2.29) |

55.1 (2.17) |

88.3 (3.48) |

81.1 (3.19) |

860.0 (33.86) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 12.8 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 12.8 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 8.9 | 7.5 | 8.1 | 9.3 | 12.6 | 13.5 | 133.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 75 | 68 | 64 | 64 | 61 | 58 | 59 | 67 | 74 | 79 | 82 | 69 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 100.2 | 92.0 | 139.4 | 176.2 | 224.5 | 290.7 | 300.8 | 285.7 | 220.7 | 163.4 | 89.7 | 54.1 | 2,137.4 |

| Source: Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia[35] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

As in other cities of the Balkans that went under Ottoman urban development, the population largely converted to Islam in the 16th century, although part of the former Catholic converts professed a form of crypto-Christianity (laramanë). An aspect of this new urban character is evidenced by the demographics of workshop owners; 227 of 246 workshops of Prizren were run by Muslims in 1571.[36] As the Catholic population dwindled prelatic missions and reports in the region increased. Marino Bizzi, Archbishop of Antivari, in his 1610 report stated that Prizren had 8.600 large houses.[37] The Christian part of the city was formed by Catholics (30 households), whose churhces had been reduced to two (from a total of 80), and Orthodox, who outnumbered them and spoke the Dalmatian language.[37] In 1623, Pjetër Mazreku, who in 1624 succeeded Bizzi as Archbishop of Antivari, reported that the city was populated mostly by Muslims, who numbered 12,000 and were mostly Albanians.[38] The Catholics of the city spoke Albanian and Slavic and 200 of them were Albanians.[39][38] The Orthodox element was composed of 600 Serbs.[38] In 1857, Russian Slavist Alexander Hilferding's publications place the Muslim families at 3,000, the Orthodox ones at 900 and the Catholics at around 100 families.[40] The Ottoman census of 1876, placed the total population at around 44,000.

| Demographics | |||||||||||||

| Year | Albanians | % | Bosniaks | % | Serb | % | Turk | % | Roma | % | Others | % | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 cens. | 132,591 | 75.58 | 19,423 | 11.1 | 10,950 | 6.24 | 7,227 | 4.1 | 3,96 3 | 2.3 | 1,259 | 0.7 | 175,413 |

| 1998 | n/a | n/a | 38,500 | n/a | 8,839 | n/a | 12,250 | n/a | 4,500 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| January 2000 | 181,531 | 76.9 | 37,500 | 15.9 | 258 | 0.1 | 12,250 | 5.2 | 4,500 | 1.9 | n/a | n/a | 236,000 |

| March 2001 | 181,748 | 81.9 | 22,000 | 9.9 | 252 | 0.1 | 12,250 | 5.5 | 5,424 | 2.4 | n/a | n/a | 221,674 |

| May 2002 | 182,000 | 79.6 | 29,369 | 12.8 | 197 | 0.09 | 11,965 | 5.2 | 4,400 | 1.9 | 550 | 0.25 | 228,481 |

| December 2002 | 180,176 | 81.6 | 21,266 | 9.6 | 221 | 0.09 | 14,050 | 6.4 | 5,148 | 2.3 | n/a | n/a | 221,374 |

| Source: For 1991: Census data, Federal Office of Statistics in Serbia (figures to be considered as unreliable). 1998 and 2000 minority figures from UNHCR in Prizren, January 2000. 2000 Kosovo Albanian figure is an unofficial OSCE estimate January–March 2000. 2001 figures come from German KFOR, UNHCR and IOM last update March 2, 2001. May 2002 statistics are joint UN, UNHCR, KFOR, and OSCE approximations. December 2002 figures are based on survey by the Local Community Office. All figures are estimates. Ref: OSCE .pdf [dead link] | |||||||||||||

According to the 1991 census conducted by the Yugoslav authorities, the municipality of Prizren had a population of 200,584 citizens:

- 157,518 (78.53%) Albanians

- 11,371 (5.67%) Serbs and Montenegrins

- other' [3]

According to the same census, the city of Prizren had 92,303 citizens.

Just before the Kosovo War in 1998, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe estimated the population of the municipality of Prizren:

- Albanians 78%

- Serbs 5%

- others 17%

According to a United Nations estimate in 2003, the city had about 124,000 citizens, most being ethnic Albanians. According to the World Gazetteer, the city only had 131,247 residents in 2010.[41]

Sister cities

Bingen am Rhein, Germany

Bingen am Rhein, Germany Tiranë, Albania

Tiranë, Albania Durrës, Albania

Durrës, Albania Vlorë, Albania

Vlorë, Albania Sarandë, Albania

Sarandë, Albania Istanbul, Turkey

Istanbul, Turkey Zagreb, Croatia

Zagreb, Croatia Osijek, Croatia

Osijek, Croatia Mamuša, Kosovo

Mamuša, Kosovo

Notable people from Prizren

- Ivica Dačić, Serbian politician, Prime Minister of Republic of Serbia

See also

Notes and references

Notes:

References:

- ^ "Preliminary Results of the Kosovo 2011 population and housing census". The statistical Office of Kosovo. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ THERANDA (Prizren) Yugoslavia, The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, A Roman town about 76 km (47.22 mi) SW of Priština on the Bistrica river. It lay on the direct route from Lissos in Macedonia to Naissus in Moesia Superior. The town continued to exist during the 4th to 6th century, but was of far greater significance during the mediaeval period and was even capital of Serbia for a short time during the 14th century.

- ^ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Procopius/Buildings/4B*.html

- ^ DETELIć, Mirjana: Градови у хришћанској и муслиманској епици, Belgrade, 2004, ISBN 86-7179-039-8.

- ^ Ducellier, Alain (1999-10-21). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 5, c.1198-c.1300. Cambridge University Press. p. 780. ISBN 9780521362894. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

The question of Illyrian continuity was already addressed by Jireček, 1916 p69-70, and in the same collection, p127-8, admitting that the territory occupied by the Albanians extended, prior to Slav expansion, from Scutari to Valona and from Prizren to Ohrid, utilizing in particular the correspondence of Demetrios Chomatenos; Circovic ((1988) p347; cf Mirdita (1981)

- ^ Malcolm, Noel (1996). Bosnia: A Short History. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-8147-5561-7.

- ^ a b Fine, John V. A. (John Van Antwerp) (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. p. 7,. ISBN 9780472082605. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Novaković, R (1966). "O nekim pitanjima područja današnje Metohije krajem XII i početkom XIII veka". Zbornik Radova Vizantološkog Instituta. 9: 195–215.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Malcolm, Noel (1996). Bosnia: A Short History. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-8147-5561-7.

- ^ http://www.komuna-prizreni.org/repository/docs/PRIZREN-CITY_MUSEUM.pdf [dead link]

- ^ http://muja-live.piczo.com/vilajetetshqiptare?cr=2&linkvar=000044[dead link]

- ^ "Prizren history".

- ^ "Prizren history".

- ^ "Die aktuelle deutsche Unterstützung für die UCK". Trend.infopartisan.net. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- ^ Malcolm, Noel (2002). Kosovo: A short history. p. 311. ISBN 0-330-41224-8.

- ^ Human Rights Watch, 2001 Under orders: war crimes in Kosovo, page 339. ISBN 1-56432-264-5

- ^ Human Rights Watch, 2001 Under orders: war crimes in Kosovo, page 338. ISBN 1-56432-264-5

- ^ Andras Riedlmayer, Harvard University Kosovo Cultural Heritage Survey

- ^ The Human Rights Centre, Law Faculty, University of Pristina, 2009 Ending Mass Atrocities: Echoes in Southern Cultures, page 3

- ^ a b c d e f g "Reconstruction Implementation Commission". Site on protection list. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Failure to Protect: Anti-Monority Violence in Kosovo , March 2004. Wuman Right Watch. 2004. p. 9.

- ^ Warrander, Gail (2008). Kosovo. Bradt. p. 191.

- ^ Diplomatic Observer Official Language

- ^ OSCE Implementation of the Law on the Use of Languages by Kosovo Municipalities

- ^ "Report of Forum #2, Museum of Kosovo". Government of Kosovo, Ministry of Culture, Youth, and Sports. March 5, 2009.

- ^ Cultural Heritage Without Borders, Workshop “Integrated conservation"; preservation and urban Planning” in Prizren November 2002

- ^ "Eclectic Prizren: "A city of everyone"". SETimes.com. 2010-10-25. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- ^ "Walkable Map of Pristina – Future Of Pristina – Kosovo – ESI". Esiweb.org. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- ^ just a mention of the legend

- ^ "Споменици културе у Србији". Spomenicikulture.mi.sanu.ac.rs. 1955-05-14. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- ^ -ana aus türk. hane Haus; aufgenommen sind Wörter wie kahve-hane Kaffeehaus, tabehane (tabahana) = tabak-k. Gerberhaus, skr. kaväna, tabakäna;

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2004). Historical dictionary of Kosova. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 145. ISBN 0-8108-5309-4.

- ^ "Cultural Heritage in Kosovo" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c "Bosnia and herzegovina republika srpska national assembly elections". Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. 1997-11-22/23. p. 32. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) [dead link] - ^ "Monthly and annual means, maximum and minimum values of meteorological elements for the period 1961-1990" (in Serbian). Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- ^ Egro, Dritan (2010). Oliver Jens Schmitt (ed.). Islam in the Albanian lands (XVth-XVIIth century). Religion und Kultur Im Albanischsprachigen Südosteuropa. Peter Lang. pp. 13–50. ISBN 9783631602959. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ a b Bizzi, Marino, Relatione della visita fatta da me, Marino Bizzi, Arcivescovo d'Antivari, nelle parti della Turchia, Antivari, Albania et Servia alla santità di nostro Signore papa Paolo V (Report of Marino Bizzi, Archbishop of Bar (Antivari), on his visit to Turkey, Bar, Albania and Serbia in the year 1610)

{{citation}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ a b c . Gjurmime albanologjike: Seria e shkencave historike. Vol. 1. Albanological Institute of Pristina. 1972 http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=NZriAAAAMAAJ&q=Prizren+%2B+Mazreku&dq=Prizren+%2B+Mazreku&hl=en&sa=X&ei=wZGuUMaIJu_44QTBiYCAAw&ved=0CEkQ6AEwCQ.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Fine, John (2006-03-02). When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans: A Study of Identity in Pre-Nationalist Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia in the Medieval and Early-Modern Periods. University of Michigan Press. p. 410. ISBN 9780472114146. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ Fishta, Gjergj (2006-03-03). Elsie Robert (ed.). The Highland Lute. I.B.Tauris. pp. 452–. ISBN 9781845111182. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ World Gazzetteer (2010). "Kosovo: largest cities and towns and statistics of their population". Retrieved 6 August 2010.

External links

- Municipality of Prizren by Republic of Kosovo

- Prizren, Serbian capital Template:Sr icon

- University of Prizren Template:Sq icon

- Prizren pictures through time Template:Sq icon