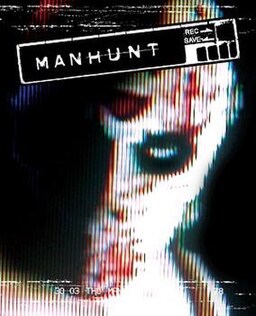

Manhunt (video game)

| Manhunt | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Rockstar North |

| Publisher(s) | Rockstar Games |

| Designer(s) | Christian Cantamessa |

| Series | Manhunt |

| Engine | RenderWare |

| Platform(s) | Windows PlayStation 2 Xbox |

| Release | PlayStation 2 Microsoft Windows, Xbox |

| Genre(s) | Stealth, Psychological horror |

| Mode(s) | Single-player (Third-person view) |

Manhunt is a stealth-based psychological horror video game developed by Rockstar North and published by Rockstar Games. It was released in North America on November 18, Template:Vgy for the PlayStation 2 and on April 20, Template:Vgy for Xbox and PC, and in Europe on November 21 for the PS2 and on April 23 for the Xbox and PC. Although it received positive reviews by critics, Manhunt is well known for controversy, due to the level of graphic violence in the game. The game was banned in several countries, and implicated in a murder by the UK media, although this implication was later rejected by the police and courts.[1][2][3] In October Template:Vgy, Manhunt 2 was released to even more controversy.

As of March 26, 2008, the Manhunt franchise has sold 1.7 million copies worldwide.[4] At the 7th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards, the game was nominated for "Console Action Adventure Game of the Year".[5] In 2010, it was included in 1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die,[6] and listed at #85 in IGN's "Top 100 PlayStation 2 Games".[7]

Gameplay

Manhunt is a stealth-based psychological horror game played from a third-person perspective. The game consists of twenty levels, called "scenes", as well as four unlockable bonus levels.[8] Players survive the scenes by dispatching enemy gang members, known as "Hunters", occasionally with firearms, but primarily by stealthily executing them.[9]

At the end of each scene, the player is graded based on their performance, and awarded one to five stars. Unlockable content becomes available only when the player achieves three or more stars on a certain number of levels. On normal difficulty (called "Fetish"), the player can earn only four stars; one is awarded for completing the scene under a certain amount of time, and one to three stars are awarded based on the brutality of the executions carried out during the scene. On hard difficulty (called "Hardcore"), the player is graded out of five stars; one for speed, one to three for brutality and one for simply completing the scene. To gain the maximum number of stars, a set number of brutal executions must be carried out over the course of each scene; face-to-face fighting does not award stars.[9]

In order to carry out executions, the player must approach a hunter from behind, undetected. To facilitate this, each scene is full of "dark spots" (shadows where the player can hide). Hunters cannot see into the shadows (unless they see the player actually entering the area). A standard technique in the game is to hide in the shadows and tap a wall to attract the attention of a nearby hunter. When he has examined the area and is moving away, the player can emerge from the shadows behind him, and execute him.[10]

The game has three 'levels' of execution, with each level progressively more violent and graphic than the last. Level 1 executions are quick and not very bloody, Level 2 are considerably more gory, and Level 3 are over-the-top blood-soaked murders. The player him/herself is entirely in control of which level they use; once the player has locked onto an enemy, the lock-on reticule changes color over time to indicate the level; white (level 1), yellow (level 2), and, finally, red (level 3).[11][12] As an example, if using a plastic bag, a level 1 kill involves Cash simply using the bag to suffocate the hunter. A level 2 kill involves Cash placing the bag over the hunter's head and kneeing them repeatedly in the face. A level 3 kill sees Cash strangle the hunter and turn them around to punch them in the face, whilst the hunter struggles to free himself and gasps for air. Eventually, Cash snaps the hunter's neck.

Over the course of the game, the player can use a wide variety of weapons, including plastic bags, baseball bats, crowbars and a variety of bladed items. Later in the game, firearms become available (which cannot be used for executions). If the player is running low on health, painkillers are available throughout each scene.[10] The player also has a stamina meter which depletes as he sprints, but automatically replenishes when he stands still.[9]

Manhunt also makes use of the PlayStation 2's optional USB Microphone and the Xbox Live microphone feature on the Xbox in their respective versions of the game. When such a device is connected, the player can use the sound of his or her own voice to distract in-game enemies. This in turn adds an extra element to the stealth aspect of the game, as the player must refrain from making noises such as coughing, as these sounds too can attract the attention of any nearby hunters.[9]

Synopsis

The game's story follows a supposedly executed death row inmate who is forced to participate in a series of snuff films for former film producer and now underground snuff director, Lionel Starkweather (voiced by Brian Cox).

Set in dilapidated Carcer City, the story opens with a news anchor (Kate Miller) reporting on James Earl Cash (Stephen Wilfong), a death row prisoner recently executed by lethal injection. In reality, however, Cash awakens to hear a voice coming from an earpiece, revealing his lethal injection was only a sedative. The voice, who refers to himself as "The Director", promises Cash his freedom, but only if Cash follows his instructions. He must move through an abandoned section of the city being patrolled by a gang called "The Hoods", murdering them as he goes, all the while being filmed by CCTV. Cash successfully dispatches the Hoods, but despite the Director's promise of freedom, he is beaten and thrown into the back of a van by a group of private security experts ("The Cerberus").

Cash is then told by the Director that he has more to do before the night is out. He is subsequently taken to various locations around the city and forced to face off against a series of increasingly dangerous gangs. First, he is pitted against a group of white supremacists and Neo-Nazis ("The Skinz") in a scrap yard. Then, he faces a gang of former military turned mercenaries ("The Wardogs") in an abandoned zoo. Here Cash has to save members of his own family who have been kidnapped by the Wardogs and are being used as bait to lure him out. Following this, he fights a gang of Satanic Latino occultists ("The Innocentz") in a shopping center. During this conflict, Cash discovers that the Director has had his family killed despite his promise to let them go. After watching their deaths on a TV set up for him by the Director, Cash vows revenge. After again facing the Innocentz in a factory, Cash is forced to face off, in what is supposed to be the final scene of the film, against a gang of schizophrenics and sociopaths ("The Smileys") who have taken over an insane asylum. Here, Cash unexpectedly survives, killing the Smileys and escaping the asylum. As such, the Director deploys the remaining Wardogs, led by the vicious Ramirez (Chris McKinney), to hunt Cash down and kill him.

As Cash flees the asylum, the journalist from the beginning of the game suddenly arrives in her car and rescues him. She explains that the Director is actually Lionel Starkweather, a former film producer who was forced to leave the industry due to a "scandal." The reporter has been putting together evidence about Starkweather's snuff movies for months, and now she has enough to expose him. First, however, she needs to retrieve some of this evidence from her apartment. Meanwhile, Starkweather orders the chief of the Carcer City Police Department, Gary Schaffer, to bring both Cash and the journalist to him. Protecting her from the police, Cash takes the journalist safely to her apartment, and from there, heads off to deal with Starkweather personally. Killing off the remaining Wardogs, including Ramirez, Cash must then evade SWAT teams, before making his way through a train yard, only to be cornered by the police. They begin to beat him, but suddenly they are ambushed by the Cerberus, who recapture Cash and bring him to Starkweather's mansion. There, they are about to kill Cash, when Piggsy - a mentally retarded, chainsaw-wielding psychopath, who wears a pig's head as a mask and is normally kept chained up in Starkweather's attic - breaks free. This distraction allows Cash to work his way through the garden and mansion, killing members of the Cerberus along the way. He finally reaches the upper levels of the mansion, where he and Piggsy stalk one another. Cash triumphs after luring Piggsy onto a grate that collapses under his weight. After using Piggsy's chainsaw to hack his way through the last of the Cerberus, Cash finally confronts Starkweather in his office, disemboweling and decapitating him with the chainsaw.

Later that night, the media arrive at the mansion, with the journalist exposing Starkweather's snuff ring and police complicity. Cash, however, is nowhere to be found.

Development

A preview of Manhunt was released on the IGN website on 22 August 2003, talking about the mechanics of the game, many of which were brought over from the Grand Theft Auto franchise.[13] In September 2003, GamesMaster published a preview of Manhunt, commenting "[Rockstar North has] scraped its imagination to further twist the way games are made in the future and delivers a chiseled, no-apologies assault on gaming standards. [...] it possesses a warped subtlety that questions game reality... It creates a barren, harsh, violent experience and then punctures it with something trippy and darkly comic..."[14]

Many more news outlets, including magazines and websites including GameSpy, GameSpot and IGN, all previewed Manhunt from late 2003 to early 2004,[15][16][17][18][19] when the game was released on Microsoft Windows and Xbox.

Reception

| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| GameRankings | (PS2) 77.05%[20] (PC) 76.16%[21] (Xbox) 75.86%[22] |

| Metacritic | (PS2) 76/100[23] (PC) 75/100[24] (Xbox) 74/100[25] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| 1Up.com | C[11] |

| Edge | 8/10[27] |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | 10/10 |

| Eurogamer | 7/10 |

| Game Informer | 9.5/10[26] |

| GameSpot | 8.4/10[10] |

| IGN | 8.5/10[8] |

Manhunt received generally favorable reviews. The PlayStation 2 version currently holds scores of 77% and 76% on aggregate sites GameRankings and Metacritic respectively.[20][23]

The game's dark nihilistic tone and violent nature was singled out by many critics as representing something unique in the world of video gaming. GameSpot, for example, concluded that "like it or not, the game pushes the envelope of video game violence and shows you countless scenes of wholly uncensored, heavily stylized carnage."[10] Game Informer praised the game's audacity and competent technical capabilities, stating "it's a frightening premise that places gamers in a psychological impasse. The crimes that you commit are unspeakable, yet the gameplay that leads to these horrendous acts is so polished and fierce that it's thrilling."[26] IGN complimented the game's overall challenge, calling it a "solid, deep experience for seasoned gamers pining for some hardcore, challenging games."[8]

The Chicago Tribune were especially complimentary of the game, arguing that it marked a significant moment in video gaming history;

Manhunt is easily the most violent game ever made. It will likely be dismissed by many as a disgusting murder simulator with no reason to exist. But Manhunt also is the Clockwork Orange of video games, holding your eyes open so as to not miss a single splatter -- asking you, is this really what you enjoy watching? Had Manhunt been poorly made, using the snuff film angle as a cheap gimmick, the game would have been shameful and exploitative. What elevates it to a grotesque, chilling work of art is both presentation and game play. Manhunt is solid as a game; it's engaging to use stealth as you creep through the streets of this wicked city, using your smarts to avoid death, while dishing out much of your own. It's Ubisoft's Splinter Cell meets the cult Faces of Death videos [...] If Manhunt succeeds at retail, it will say more about America's fascination with violence than any political discourse or social debate. That makes Manhunt the most important video game of the last five years.[28]

The game did receive some criticisms however. Certain gameplay elements, such as the shooting mechanics, were called "frustrating" by Eurogamer, who claimed that "more than half the time the targeting reticule refuses to acknowledge an oncoming enemy until they're virtually in front of you." GameSpot concurred, noting that the "AI is much worse in the more action-oriented levels."[10] 1UP.com was also critical, asserting that one quickly became "tired of [the] violence [...] AI quirks [and] repetitive level design."[11]

Controversy

The controversy surrounding the game stems primarily from the graphic manner in which the player executes enemies. In 2007, former Rockstar employee Jeff Williams revealed that even the game's staff were somewhat uncomfortable about the level of violence; "there was almost a mutiny at the company over that game."[29] Williams explained that the game "just made us all feel icky. It was all about the violence, and it was realistic violence. We all knew there was no way we could explain away that game. There was no way to rationalize it. We were crossing a line."[30]

The violence in the game drew the attention of U.S. Representative Joe Baca, who was the sponsor of a legislation to fine those who sell adult-themed games to players younger than 17. Baca said of Manhunt, "it's telling kids how to kill someone, and it uses vicious, sadistic and cruel methods to kill."[31] The media was also drawn into the debate. For example, The Globe and Mail wrote "Manhunt is a venal disconnect for the genre. There's no challenge, just assembly-line, ritualistic slaughter. It's less a video game and more a weapon of personal destruction. This is about stacking bodies. Perhaps the scariest fact of all: Manhunt is so user-friendly that any sharp 12-year-old could navigate through the entire game in one sitting."[32]

Toronto Star writer Ben Rayner, however, praised the relevance of the game, defending its violence and graphic nature as very much a product of its time, and condemning calls to have it banned;

As entertainment and cultural artifact, Manhunt is totally disturbing. But so is the evening news, the "I'll eat anything for money" lunacy of Fear Factor and the unfettered, misanthropic gunplay of Bad Boys II, so I will defend until my last breath Rockstar's right to sell this stuff to me and anyone else who wants it. Do I think games such as these could have dire psychological consequences, particularly for young people? As always, I remain agnostic on the matter. Who knows, really? The debate will never be resolved. The American military obviously thinks there's something there: The troubling new TV ad campaign for the U.S. reserves lures potential young soldiers with tales of adventure accompanied by blatant, video-game-styled animation. And, curiously, no one has complained about or tried to ban SOCOM: U.S. Navy SEALs, in which stealth and killing figure even more heavily than in Manhunt.[33]

The murder of Stefan Pakeerah

The controversy surrounding Manhunt reached a peak on July 28, 2004, when the game was linked to the murder of Stefan Pakeerah (14) by his friend Warren Leblanc (17) in Leicestershire, England. Initial media reports claimed that police had found a copy of the game in Leblanc's bedroom, which police had seized as evidence, and Giselle Pakeerah, the victim's mother, stated "I think that I heard some of Warren's friends say that he was obsessed by this game. To quote from the website that promotes it, it calls it a psychological experience, not a game, and it encourages brutal killing. If he was obsessed by it, it could well be that the boundaries for him became quite hazy."[34] Stefan's father, Patrick, added "they were playing a game called Manhunt. The way Warren committed the murder this is how the game is set out, killing people using weapons like hammers and knives. There is some connection between the game and what he has done."[34] Patrick continued "The object of Manhunt is not just to go out and kill people. It's a point-scoring game where you increase your score depending on how violent the killing is. That explains why Stefan's murder was as horrific as it was. If these games influence kids to go out and kill, then we do not want them in the shops."[35] A spokesman for the Entertainment and Leisure Software Publishers' Association (ELSPA) responded to the accusations by stating "We sympathize enormously with the family and parents of Stefan Pakeerah. However, we reject any suggestion or association between the tragic events and the sale of the video game Manhunt. The game in question is classified 18 by the British Board of Film Classification and therefore should not be in the possession of a juvenile. Simply being in someone's possession does not and should not lead to the conclusion that a game is responsible for these tragic events."[36]

During the subsequent media coverage, the game was removed from shelves by some vendors, including both UK and international branches of GAME and Dixons. Rockstar responded to this move by stating, "we have always appreciated Dixons as a retail partner, and we fully respect their actions. We are naturally very surprised and disappointed that any retailer would choose to pull any game [...] We reject any suggestion or association between the tragic events and the sale of Manhunt." Rockstar also reiterated that the game was intended for adults only; "Rockstar Games is a leading publisher of interactive entertainment geared towards mature audiences, and [it] markets its games responsibly, targeting advertising and marketing only to adult consumers ages 18 and older."[37] As the media speculated that the game could be banned completely, there was a "significantly increased" demand for it both from retailers and on Internet auction sites.[38] Giselle Pakeerah responded to this by saying "it doesn't really come as surprise, they say no publicity is bad publicity. But I must say I'm saddened and disappointed. The content of this game is contemptible. It's a societal hazard and my concern is to get it off the shelves as there's enough violence in society already."[39]

Shortly after the murder, US attorney Jack Thompson, who has campaigned against violence in video games, claimed that he had written to Rockstar after the game was released, warning them that the nature of the game could inspire copycat killings; "I wrote warning them that somebody was going to copycat the Manhunt game and kill somebody. We have had dozens of killings in the U.S. by children who had played these types of games. This is not an isolated incident. These types of games are basically murder simulators. There are people being killed over here almost on a daily basis."[40] Soon thereafter, the Pakeerah family hired Thompson with the aim of suing Sony and Rockstar for £50 million in a wrongful death claim.[41]

However, on the same day that Thompson was hired, the police officially denied any link between the game and the murder, citing drug-related robbery as the motive and revealing that the game had been found in Pakeerah's bedroom, not Leblanc's, as originally reported in the media.[1][3] According to a spokesperson for Leicestershire Constabulary, "the video game was not found in Warren LeBlanc's room, it was found in Stefan Pakeerah's room. Leicestershire Constabulary stands by its response that police investigations did not uncover any connections to the video game, the motive for the incident was robbery."[2] The presiding judge also placed sole responsibility with Leblanc in his summing up, after sentencing him to life.[3] The Pakeerah's case against Sony and Rockstar was dropped soon thereafter.[42]

Three years later, in the build-up to the release of Manhunt 2, the controversy re-ignited. Two days after announcing the game, which was set for release in July, Take-Two Interactive (Rockstar's parent company) issued a statement which read, in part; "We are aware that in direct contradiction to all available evidence, certain individuals continue to link the original Manhunt title to the Warren Leblanc case in 2004. The transcript of the court case makes it quite clear what really happened. At sentencing the Judge, defense, prosecution and Leicester police all emphasized that Manhunt played no part in the case."[43] Later that day, however, Patrick and Giselle Pakeerah condemned the decision to release a sequel, and insisted that Manhunt was a factor in their son's murder. Upon the announcement of the sequel, Patrick stated "I'm very disappointed. This is rubbing salt into the wounds in the month we will be marking the anniversary of Stefan's death. I'm very surprised they are doing this after all that has happened and all the publicity." Giselle added "It is an insult to my son's memory that they have announced this game in the month we will be marking this anniversary. These game moguls are making a lot of money out of games which are morally indecent. Why do they have to pump more violence into society?" Leicester East MP Keith Vaz supported the Pakeerahs, claiming he was "astonished" that Rockstar were making a sequel; "It is contempt for those who are trying very hard to ensure something is done to control the violent nature of these games."[44]

Several weeks later, Jack Thompson vowed to have Manhunt 2 banned, claiming that the police were incorrect in asserting the game had belonged to Pakeerah, and that Take-Two were lying about the incident;

[I] have been asked by individuals in the United Kingdom to help stop the distribution of Take-Two/Rockstar's hyperviolent video game Manhunt 2 in that country due out this summer. The game will feature stealth murder and torture. The last version allowed suffocation of victims with plastic bags. The original Manhunt was responsible for the bludgeoning death of a British youth by his friend who obsessively played the game. The killer used a hammer just as in the game he played. Take-Two/Rockstar, anticipating the firestorm of criticism with the release of the murder simulator sequel, is lying to the public on both sides of the pond in stating this week that the game had nothing to do with the murder.[45]

His efforts to have Manhunt 2 banned were unsuccessful.[46]

Legal status

- Australia: The game was "refused classification" on September 28, 2004 by the Classification Review Board despite having already been on sale for almost a year at the time, having earlier received a classification of 15.[47]

- Germany: On July 19, 2004, the Amtsgericht in Munich confiscated all versions of Manhunt for violation of § 131 StGB ("representation of violence"). According to the court, the game, portrays the killing of humans as fun, and the more violent, the more fun the killing is. They also said it glorified vigilantism, which they considered harmful per se.[48]

- New Zealand: The game was banned on December 11, 2003,[11][49] with possession deemed an offence.[50] Bill Hastings, the Chief Censor, stated "it's a game where the only thing you do is kill everybody you see [...] You have to at least acquiesce in these murders and possibly tolerate, or even move towards enjoying them, which is injurious to the public good."[51]

- North America: Following a meeting in Toronto on December 22, 2003 between Hastings and officials from the Ontario Ministry of Consumer and Business Services, Manhunt became the first computer game in Ontario to be classified as a film and was restricted to adults on February 3, 2004. Apart from Ontario, however, Manhunt had little or no classification problems elsewhere in North America. The British Columbia Film Classification Office reviewed the game after the controversy in Ontario and deemed the Mature rating by the ESRB to be appropriate.[52]

References

- ^ a b "Police reject game link to murder". BBC. August 5, 2004. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ a b Rob Fahey (August 4, 2004). "New twist to Manhunt murder allegations". GamesIndustry.biz. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ^ a b c "Teenage murderer gets life term". BBC. September 3, 2004. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ^ "Recommendation of the Board of Directors to Reject Electronic Arts Inc.'s Tender Offer" (PDF). Take-Two Interactive. March 26, 2008. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ^ "Industry News Archive". ESCMag. February 13, 2004. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ Mott, Tony (2010). 1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die. London: Quintessence Editions Ltd. p. 546. ISBN 978-1-74173-076-0.

- ^ "Top 100 PlayStation2 Games". IGN. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ a b c Douglass C. Perry (November 28, 2003). "Manhunt Review". IGN. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ a b c d "Basics". Manhunt guide (PS2). IGN. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ a b c d e Greg Kasavin (November 19, 2003). "Manhunt for PS2 Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ a b c d "Manhunt PS2 Review". 1UP.com. Retrieved 2007-02-26. Cite error: The named reference "1up" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Manhunt Review". GameChronicles. February 2, 2004. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ Douglass C. Perry (22 August 2003). "Manhunt". IGN. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ^ "M A N H U N T". Rockstar Games. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ^ IGN Staff (22 September 2003). "Manhunt in Motion". IGN. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ^ Douglass C. Perry (30 September 2003). "Manhunt: The Story". IGN. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ^ Ricardo Torres (14 October 2003). "Manhunt Preview". GameSpot. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - ^ Douglass C. Perry (30 October 2003). "Manhunt: Hands-on". IGN. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ^ Benjamin Turner (10 March 2004). "Manhunt". GameSpy. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ^ a b "Manhunt (PlayStation 2)". GameRankings. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ "Manhunt (PC)". GameRankings. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ "Manhunt (Xbox)". GameRankings. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ a b "Manhunt (PlayStation 2)". Metacritic. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ "Manhunt (PC)". Metacritic. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ "Manhunt (Xbox)". Metacritic. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- ^ a b Andrew Reiner. "Manhunt PS2 Review". Game Informer. Archived from the original on 2008-02-02. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- ^ "Manhunt Review". Edge. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Levi Buchanan (November 23, 2003). "Manhunt a solid game, but do you want the gore?". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Jeff Williams (24 July 2007). "Life During Wartime - Working at Rockstar Games". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2007-08-04. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ^ Matt Cundy (July 26, 2007). "Manhunt nearly caused a "mutiny" at Rockstar, Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas PS2 News". GamesRadar. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ^ David Gwinn (November 23, 2003). "Manhunt the next step in video game violence". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Andrew Ryan (March 6, 2004). "Belly up to the slaughter buffet". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Ben Rayner (January 25, 2004). "In my private moments, I'm a murderer". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "Store withdraws video game after brutal killing". Daily Mail. July 29, 2004. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ David Millward (July 29, 2004). "Manhunt computer game is blamed for brutal killing". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Chris Leyton (July 28, 2004). "Manhunt blamed for murder". TVG. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ^ Tor Thorsen (July 29, 2004). "Manhunt blamed for UK murder". GameSpot. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ^ "Manhunt game 'flying off shelves'". BBC. August 4, 2004. Retrieved 2006-10-12.

- ^ Justin Calvert (August 5, 2004). "Manhunt selling out in the UK". GameSpot. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ^ "Retailer pulls 'murder' video game". CNN. July 30, 2004. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ^ "Sony to be sued over Manhunt murder". Out-law.com. August 2, 2004. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ^ "Jack Thompson versus Manhunt 2". N4G. February 23, 2007. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ Tom Bramwell (February 8, 2007). "Manhunt 2 excuses in early". Eurogamer. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ Tim Ingram (February 8, 2007). "Murder victim's parents condemn Manhunt sequel". MCVUK. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ "Jack Thompson versus Manhunt 2". N4G. February 23, 2007. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- ^ "GTA Publisher, Jack Thompson Settle Lawsuit". GamePolitics.com. April 19, 2007. Retrieved 2010-11-27.

- ^ Tony Smith (September 30, 2004). "Australia bans Manhunt". The Register. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Volker Briegleb. "Brutalo-Spiel bundesweit beschlagnahmt". onlinekosten.de. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ^ "Banning of Manhunt". OFLC. Archived from the original on October 1, 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993, 131

- ^ Tor Thorsen (December 12, 2003). "Manhunt banned in New Zealand". GameSpot. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ^ "Opinion Review: In the Matter of Manhunt published by Rockstar Games" (PDF). British Columbia Film Classification Office. February 6, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-01-14. Retrieved 2006-10-12.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2006-02-14 suggested (help)