Fracking

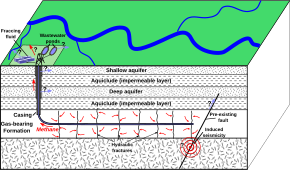

Schematic depiction of hydraulic fracturing for shale gas. | |

| Process type | Mechanical |

|---|---|

| Industrial sector(s) | Mining |

| Main technologies or sub-processes | Fluid pressure |

| Product(s) | Natural gas Petroleum |

| Inventor | Floyd Farris; J.B. Clark (Stanolind Oil and Gas Corporation) |

| Year of invention | 1947 |

Hydraulic fracturing is the fracturing of rock by a pressurized liquid. Some hydraulic fractures form naturally—certain veins or dikes are examples. Induced hydraulic fracturing or hydrofracturing is a technique in which typically water is mixed with sand and chemicals, and the mixture is injected at high pressure into a wellbore to create small fractures (typically less than 1mm), along which fluids such as gas, petroleum, uranium-bearing solution, and brine water may migrate to the well.[1] Hydraulic pressure is removed from the well, then small grains of proppant (sand or aluminium oxide) hold these fractures open once the rock achieves equilibrium. The technique is very common in wells for shale gas, tight gas, tight oil, and coal seam gas[2][3] and hard rock wells. This well stimulation is usually conducted once in the life of the well and greatly enhances fluid removal and well productivity, but there has been an increasing trend towards multiple hydraulic fracturing as production declines.

The process is commonly known as fracking, but within the industry the term frac is preferable to frack. However, fracturing would be used rather than fracing. A different technique where only acid is injected is referred to as acidizing.

The first experimental use of hydraulic fracturing was in 1947, and the first commercially successful applications were in 1949. As of 2012, 2.5 million hydraulic fracturing jobs have been performed on oil and gas wells worldwide, more than one million of them in the United States.[4][5]

Proponents of hydraulic fracturing point to the economic benefits from the vast amounts of formerly inaccessible hydrocarbons the process can extract.[6][7] Opponents of hydraulic fracturing point to environmental risks, including contamination of ground water, depletion of fresh water, contamination of the air, noise pollution, the migration of gases and hydraulic fracturing chemicals to the surface, surface contamination from spills and flow-back, and the health effects of these.[8] There are increases in seismic activity, mostly associated with deep injection disposal of flowback and produced brine from hydraulically fractured wells.[9] For these reasons hydraulic fracturing has come under international scrutiny, with some countries protecting it,[10] and others suspending or banning it.[11][12] Some of those countries, including most notably the UK have recently lifted their bans, choosing to focus on regulation instead of outright prohibition. The European Union[13] is in the process of applying regulation to permit this to take place.

Geology

Mechanics

Fracturing in rocks at depth tends to be suppressed by the confining pressure, due to the immense load caused by the overlying rock strata and the cementation of the formation. This is particularly so in the case of "tensile" (Mode 1) fractures, which require the walls of the fracture to move apart, working against this confining pressure. Hydraulic fracturing occurs when the effective stress is overcome sufficiently by an increase in the pressure of fluids within the rock, such that the minimum principal stress becomes tensile and exceeds the tensile strength of the material.[14][15] Fractures formed in this way will in the main be oriented in the plane perpendicular to the minimum principal stress and for this reason induced hydraulic fractures in well bores are sometimes used to determine the orientation of stresses.[16] In natural examples, such as dikes or vein-filled fractures, the orientations can be used to infer past states of stress.[17]

Veins

Most mineral vein systems are a result of repeated hydraulic fracturing of the rock during periods of relatively high pore fluid pressure. This is particularly noticeable in the case of "crack-seal" veins, where the vein material can be seen to have been added in a series of discrete fracturing events, with extra vein material deposited on each occasion.[18] One mechanism to demonstrate such examples of long-lasting repeated fracturing is the effect of seismic activity, in which the stress levels rise and fall episodically and large volumes of connate water may be expelled from fluid-filled fractures during earthquakes. This process is referred to as "seismic pumping".[19]

Dikes

Low-level minor intrusions such as dikes propagate through the crust in the form of fluid-filled cracks, although in this case the fluid is magma. In sedimentary rocks with a significant water content the fluid at the propagating fracture tip will be steam.[20]

Non-hydraulic fracturing

Fracturing as a method to stimulate shallow, hard rock oil wells dates back to the 1860s. It was applied by oil producers in the US states of Pennsylvania, New York, Kentucky, and West Virginia by using liquid and later also solidified nitroglycerin. Later, the same method was applied to water and gas wells. The idea to use acid as a nonexplosive fluid for well stimulation was introduced in the 1930s. Due to acid etching, fractures would not close completely and therefore productivity was increased.[21]

Hydraulic fracturing in oil and gas wells

The relationship between well performance and treatment pressures was studied by Floyd Farris of Stanolind Oil and Gas Corporation. This study became a basis of the first hydraulic fracturing experiment, which was conducted in 1947 at the Hugoton gas field in Grant County of southwestern Kansas by Stanolind.[2][22] For the well treatment 1,000 US gallons (3,800 L; 830 imp gal) of gelled gasoline (essentially napalm) and sand from the Arkansas River was injected into the gas-producing limestone formation at 2,400 feet (730 m). The experiment was not very successful as deliverability of the well did not change appreciably. The process was further described by J.B. Clark of Stanolind in his paper published in 1948. A patent on this process was issued in 1949 and an exclusive license was granted to the Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Company. On March 17, 1949, Halliburton performed the first two commercial hydraulic fracturing treatments in Stephens County, Oklahoma, and Archer County, Texas.[22] Since then, hydraulic fracturing has been used to stimulate approximately a million oil and gas wells[23] in various geologic regimes with good success.

In contrast with the large-scale hydraulic fracturing used in low-permeability formations, small hydraulic fracturing treatments are commonly used in high-permeability formations to remedy skin damage at the rock-borehole interface. In such cases the fracturing may extend only a few feet from the borehole.[24]

In the Soviet Union, the first hydraulic proppant fracturing was carried out in 1952. Other countries in Europe and Northern Africa to use hydraulic fracturing included Norway, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Austria, France, Italy, Bulgaria, Romania, Turkey, Tunisia, and Algeria.[25]

Massive hydraulic fracturing

Pan American Petroleum applied the first massive hydraulic fracturing (also known as high-volume hydraulic fracturing) treatment in Stephens County, Oklahoma, USA in 1968. The definition of massive hydraulic fracturing varies somewhat, but is generally used for treatments injecting greater than about 150 short tons, or approximately 330,000 pounds (136 metric tonnes), of proppant.[26]

American geologists became increasingly aware that there were huge volumes of gas-saturated sandstones with permeability too low (generally less than 0.1 millidarcy) to recover the gas economically.[26] Starting in 1973, massive hydraulic fracturing was used in thousands of gas wells in the San Juan Basin, Denver Basin,[27] the Piceance Basin,[28] and the Green River Basin, and in other hard rock formations of the western US. Other tight sandstones in the US made economic by massive hydraulic fracturing were the Clinton-Medina Sandstone, and Cotton Valley Sandstone.[26]

Massive hydraulic fracturing quickly spread in the late 1970s to western Canada, Rotliegend and Carboniferous gas-bearing sandstones in Germany, Netherlands onshore and offshore gas fields, and the United Kingdom sector of the North Sea.[25]

Horizontal oil or gas wells were unusual until the 1980s. Then in the late 1980s, operators in Texas began completing thousands of oil wells by drilling horizontally in the Austin Chalk, and giving massive slickwater hydraulic fracturing treatments to the wellbores. Horizontal wells proved much more effective than vertical wells in producing oil from the tight chalk;[29] the shale runs horizontally so a horizontal well reached much more of the resource.[30] In 1991, the first horizontal well was drilled in the Barnett Shale[30] and in 1996 slickwater fluids were introduced.[30]

Massive hydraulic fracturing in shales

Due to shale's low porosity and low permeability, technological research, development and demonstration were necessary before hydraulic fracturing could be commercially applied to shale gas deposits. In 1976 the United States government started the Eastern Gas Shales Project, a set of dozens of public-private hydraulic fracturing pilot demonstration projects.[31] During the same period, the Gas Research Institute, a gas industry research consortium, received approval for research and funding from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission.[32]

In 1997, taking the slickwater fracturing technique used in East Texas by Union Pacific Resources, now part of Anadarko Petroleum Corporation, Mitchell Energy, now part of Devon Energy, learned how to use the technique in the Barnett Shale of north Texas, which made shale gas extraction widely economical.[33][34][35] George P. Mitchell has been called the "father of fracking" because of his role in applying it in shales.[36]

As of 2013, massive hydraulic fracturing is being applied on a commercial scale to shales in the United States, Canada, and China; in addition, several countries are planning to use hydraulic fracturing for unconventional oil and gas production.[37][38][39] Some countries, e.g. the United Kingdom, have recently lifted their bans for hydraulic fracturing.[40] The European Union has adopted a recommendation for minimum principles for using high-volume hydraulic fracturing.[41]

Induced hydraulic fracturing

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) hydraulic fracturing is a process to stimulate a natural gas, oil, or geothermal energy well to maximize the extraction. The broader process, however, is defined by EPA as including the acquisition of source water, well construction, well stimulation, and waste disposal.[42]

Uses

The technique of hydraulic fracturing is used to increase the rate at which fluids, such as petroleum, water, or natural gas can be recovered from subterranean natural reservoirs. Reservoirs are typically porous sandstones, limestones or dolomite rocks, but also include "unconventional reservoirs" such as shale rock or coal beds. Hydraulic fracturing enables the production of natural gas and oil from rock formations deep below the earth's surface (generally 5,000–20,000 feet (1,500–6,100 m)), which is typically greatly below groundwater reservoirs of basins if present. At such depth, there may not be sufficient permeability or reservoir pressure to allow natural gas and oil to flow from the rock into the wellbore at economic rates. Thus, creating conductive fractures in the rock is pivotal to extract gas from shale reservoirs because of the extremely low natural permeability of shale, which is measured in the microdarcy to nanodarcy range.[43] Fractures provide a conductive path connecting a larger volume of the reservoir to the well. So-called "super fracking," which creates cracks deeper in the rock formation to release more oil and gas, will increase efficiency of hydraulic fracturing.[44] The yield for a typical shale gas well generally falls off after the first year or two, although the full producing life of a well can last several decades.[45]

While the main industrial use of hydraulic fracturing is in arousing production from oil and gas wells,[46][47][48] hydraulic fracturing is also applied:

- To stimulate groundwater wells[49]

- To precondition or induce rock to cave in mining[50]

- As a means of enhancing waste remediation processes, usually hydrocarbon waste or spills[51]

- To dispose of waste by injection into deep rock formations[52]

- As a method to measure the stress in the Earth[53]

- For heat extraction to produce electricity in enhanced geothermal systems[54]

- To increase injection rates for geologic sequestration of CO2[55]

Hydraulic fracturing of water-supply wells

Since the late 1970s, hydraulic fracturing has been used in some cases to increase the yield of drinking water from wells in a number of countries, including the US, Australia, and South Africa.[56][57][58]

Method

A hydraulic fracture is formed by pumping the fracturing fluid into the wellbore at a rate sufficient to increase pressure downhole at the target zone (determined by the location of the well casing perforations) to exceed that of the fracture gradient (pressure gradient) of the rock.[59] The fracture gradient is defined as the pressure increase per unit of the depth due to its density and it is usually measured in pounds per square inch per foot or bars per meter. The rock cracks and the fracture fluid continues further into the rock, extending the crack still further, and so on. Fractures are localized because of pressure drop off with frictional loss, which is attributed to the distance from the well. Operators typically try to maintain "fracture width", or slow its decline, following treatment by introducing into the injected fluid a proppant – a material such as grains of sand, ceramic, or other particulates, that prevent the fractures from closing when the injection is stopped and the pressure of the fluid is removed. Consideration of proppant strengths and prevention of proppant failure becomes more important at greater depths where pressure and stresses on fractures are higher. The propped fracture is permeable enough to allow the flow of formation fluids to the well. Formation fluids include gas, oil, salt water and fluids introduced to the formation during completion of the well during fracturing.[59]

During the process, fracturing fluid leakoff (loss of fracturing fluid from the fracture channel into the surrounding permeable rock) occurs. If not controlled properly, it can exceed 70% of the injected volume. This may result in formation matrix damage, adverse formation fluid interactions, or altered fracture geometry and thereby decreased production efficiency.[60]

The location of one or more fractures along the length of the borehole is strictly controlled by various methods that create or seal off holes in the side of the wellbore. Hydraulic fracturing is performed in cased wellbores and the zones to be fractured are accessed by perforating the casing at those locations.[61]

Hydraulic-fracturing equipment used in oil and natural gas fields usually consists of a slurry blender, one or more high-pressure, high-volume fracturing pumps (typically powerful triplex or quintuplex pumps) and a monitoring unit. Associated equipment includes fracturing tanks, one or more units for storage and handling of proppant, high-pressure treating iron, a chemical additive unit (used to accurately monitor chemical addition), low-pressure flexible hoses, and many gauges and meters for flow rate, fluid density, and treating pressure.[62] Chemical additives are typically 0.5% percent of the total fluid volume. Fracturing equipment operates over a range of pressures and injection rates, and can reach up to 100 megapascals (15,000 psi) and 265 litres per second (9.4 cu ft/s) (100 barrels per minute).[63]

Well types

A distinction can be made between conventional or low-volume hydraulic fracturing used to stimulate high-permeability reservoirs to frac a single well, and unconventional or high-volume hydraulic fracturing, used in the completion of tight gas and shale gas wells as unconventional wells are deeper and require higher pressures than conventional vertical wells.[64] In addition to hydraulic fracturing of vertical wells, it is also performed in horizontal wells. When done in already highly permeable reservoirs such as sandstone-based wells, the technique is known as "well stimulation".[48]

Horizontal drilling involves wellbores where the terminal drillhole is completed as a "lateral" that extends parallel with the rock layer containing the substance to be extracted. For example, laterals extend 1,500 to 5,000 feet (460 to 1,520 m) in the Barnett Shale basin in Texas, and up to 10,000 feet (3,000 m) in the Bakken formation in North Dakota. In contrast, a vertical well only accesses the thickness of the rock layer, typically 50–300 feet (15–91 m). Horizontal drilling also reduces surface disruptions as fewer wells are required to access a given volume of reservoir rock. Drilling usually induces damage to the pore space at the wellbore wall, reducing the permeability at and near the wellbore. This reduces flow into the borehole from the surrounding rock formation, and partially seals off the borehole from the surrounding rock. Hydraulic fracturing can be used to restore permeability,[65] but is not typically administered in this way.

Fracturing fluids

High-pressure fracture fluid is injected into the wellbore, with the pressure above the fracture gradient of the rock. The two main purposes of fracturing fluid is to extend fractures, add lubrication, change gel strength and to carry proppant into the formation, the purpose of which is to stay there without damaging the formation or production of the well. Two methods of transporting the proppant in the fluid are used – high-rate and high-viscosity. High-viscosity fracturing tends to cause large dominant fractures, while high-rate (slickwater) fracturing causes small spread-out micro-fractures.[citation needed]

This fracture fluid contains water-soluble gelling agents (such as guar gum) which increase viscosity and efficiently deliver the proppant into the formation.[66]

The fluid injected into the rock is typically a slurry of water, proppants, and chemical additives.[67] Additionally, gels, foams, and compressed gases, including nitrogen, carbon dioxide and air can be injected. Typically, of the fracturing fluid 90% is water and 9.5% is sand with the chemical additives accounting to about 0.5%.[59][68][69] However, fracturing fluids have been developed in which the use of water has been made unnecessary, using liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and propane.[70]

A proppant is a material that will keep an induced hydraulic fracture open, during or following a fracturing treatment, and can be gel, foam, or slickwater-based. Fluids make tradeoffs in such material properties as viscosity, where more viscous fluids can carry more concentrated proppant; the energy or pressure demands to maintain a certain flux pump rate (flow velocity) that will conduct the proppant appropriately; pH, various rheological factors, among others. Types of proppant include silica sand, resin-coated sand, and man-made ceramics. These vary depending on the type of permeability or grain strength needed. The most commonly used proppant is silica sand, though proppants of uniform size and shape, such as a ceramic proppant, is believed to be more effective. Due to a higher porosity within the fracture, a greater amount of oil and natural gas is liberated.[71]

The fracturing fluid varies in composition depending on the type of fracturing used, the conditions of the specific well being fractured, and the water characteristics. A typical fracture treatment uses between 3 and 12 additive chemicals.[59] Although there may be unconventional fracturing fluids, the more typically used chemical additives can include one or more of the following:

- Acids—hydrochloric acid or acetic acid is used in the pre-fracturing stage for cleaning the perforations and initiating fissure in the near-wellbore rock.[69]

- Sodium chloride (salt)—delays breakdown of the gel polymer chains.[69]

- Polyacrylamide and other friction reducers—Decrease turbulence in fluid flow decreasing pipe friction, thus allowing the pumps to pump at a higher rate without having greater pressure on the surface.[69]

- Ethylene glycol—prevents formation of scale deposits in the pipe.[69]

- Borate salts—used for maintaining fluid viscosity during the temperature increase.[69]

- Sodium and potassium carbonates—used for maintaining effectiveness of crosslinkers.[69]

- Glutaraldehyde—used as disinfectant of the water (bacteria elimination).[69]

- Guar gum and other water-soluble gelling agents—increases viscosity of the fracturing fluid to deliver more efficiently the proppant into the formation.[66][69]

- Citric acid—used for corrosion prevention.

- Isopropanol—increases the viscosity of the fracture fluid.[69]

The most common chemical used for hydraulic fracturing in the United States in 2005–2009 was methanol, while some other most widely used chemicals were isopropyl alcohol, 2-butoxyethanol, and ethylene glycol.[72]

Typical fluid types are:

- Conventional linear gels. These gels are cellulose derivatives (carboxymethyl cellulose, hydroxyethyl cellulose, carboxymethyl hydroxyethyl cellulose, hydroxypropyl cellulose, methyl hydroxyl ethyl cellulose), guar or its derivatives (hydroxypropyl guar, carboxymethyl hydroxypropyl guar)-based, with other chemicals providing the necessary chemistry for the desired results.

- Borate-crosslinked fluids. These are guar-based fluids cross-linked with boron ions (from aqueous borax/boric acid solution). These gels have higher viscosity at pH 9 onwards and are used to carry proppants. After the fracturing job the pH is reduced to 3–4 so that the cross-links are broken and the gel is less viscous and can be pumped out.

- Organometallic-crosslinked fluids zirconium, chromium, antimony, titanium salts are known to crosslink the guar-based gels. The crosslinking mechanism is not reversible. So once the proppant is pumped down along with the cross-linked gel, the fracturing part is done. The gels are broken down with appropriate breakers.[66]

- Aluminium phosphate-ester oil gels. Aluminium phosphate and ester oils are slurried to form cross-linked gel. These are one of the first known gelling systems.

For slickwater it is common to include sweeps or a reduction in the proppant concentration temporarily to ensure the well is not overwhelmed with proppant causing a screen-off.[73] As the fracturing process proceeds, viscosity reducing agents such as oxidizers and enzyme breakers are sometimes then added to the fracturing fluid to deactivate the gelling agents and encourage flowback.[66] The oxidizer reacts with the gel to break it down, reducing the fluid's viscosity and ensuring that no proppant is pulled from the formation. An enzyme acts as a catalyst for the breaking down of the gel. Sometimes pH modifiers are used to break down the crosslink at the end of a hydraulic fracturing job, since many require a pH buffer system to stay viscous.[73] At the end of the job the well is commonly flushed with water (sometimes blended with a friction reducing chemical) under pressure. Injected fluid is to some degree recovered and is managed by several methods, such as underground injection control, treatment and discharge, recycling, or temporary storage in pits or containers while new technology is continually being developed and improved to better handle waste water and improve re-usability.[59]

Fracture monitoring

Measurements of the pressure and rate during the growth of a hydraulic fracture, as well as knowing the properties of the fluid and proppant being injected into the well provides the most common and simplest method of monitoring a hydraulic fracture treatment. This data, along with knowledge of the underground geology can be used to model information such as length, width and conductivity of a propped fracture.[59]

Injection of radioactive tracers, along with the other substances in hydraulic-fracturing fluid, is sometimes used to determine the injection profile and location of fractures created by hydraulic fracturing.[74] The radiotracer is chosen to have the readily detectable radiation, appropriate chemical properties, and a half life and toxicity level that will minimize initial and residual contamination.[75] Radioactive isotopes chemically bonded to glass (sand) and/or resin beads may also be injected to track fractures.[76] For example, plastic pellets coated with 10 GBq of Ag-110mm may be added to the proppant or sand may be labelled with Ir-192 so that the proppant's progress can be monitored.[75] Radiotracers such as Tc-99m and I-131 are also used to measure flow rates.[75] The Nuclear Regulatory Commission publishes guidelines which list a wide range of radioactive materials in solid, liquid and gaseous forms that may be used as tracers and limit the amount that may be used per injection and per well of each radionuclide.[76]

Microseismic monitoring

For more advanced applications, microseismic monitoring is sometimes used to estimate the size and orientation of hydraulically induced fractures. Microseismic activity is measured by placing an array of geophones in a nearby wellbore. By mapping the location of any small seismic events associated with the growing hydraulic fracture, the approximate geometry of the fracture is inferred. Tiltmeter arrays, deployed on the surface or down a well, provide another technology for monitoring the strains produced by hydraulic fracturing.[77]

Microseismic mapping is very similar geophysically to seismology. In earthquake seismology seismometers scattered on or near the surface of the earth record S-waves and P-waves that are released during an earthquake event. This allows for the motion along the fault plane to be estimated and its location in the earth’s subsurface mapped. During formation stimulation by hydraulic fracturing an increase in the formation stress proportional to the net fracturing pressure as well as an increase in pore pressure due to leakoff takes place.[78] Tensile stresses are generated ahead of the fracture/cracks’ tip which generates large amounts of shear stress. The increase in pore water pressure and formation stress combine and affect the weakness (natural fractures, joints, and bedding planes) near the hydraulic fracture. Dilatational and compressive reactions occur and emit seismic energy detectable by highly sensitive geophones placed in nearby wells or on the surface.[79]

Different methods have different location errors and advantages. Accuracy of microseismic event locations is dependent on the signal to noise ratio and the distribution of the receiving sensors. For a surface array location accuracy of events located by seismic inversion is improved by sensors placed in multiple azimuths from the monitored borehole. In a downhole array location accuracy of events is improved by being close to the monitored borehole (high signal to noise ratio).

Monitoring of microseismic events induced by reservoir stimulation has become a key aspect in evaluation of hydraulic fractures and their optimization. The main goal of hydraulic fracture monitoring is to completely characterize the induced fracture structure and distribution of conductivity within a formation. This is done by first understanding the fracture structure. Geomechanical analysis, such as understanding the material properties, in-situ conditions and geometries involved will help with this by providing a better definition of the environment in which the hydraulic fracture network propagates.[80] The next task is to know the location of proppant within the induced fracture and the distribution of fracture conductivity. This can be done using multiple types of techniques and finally, further develop a reservoir model than can accurately predict well performance.

Horizontal completions

Since the early 2000s, advances in drilling and completion technology have made drilling horizontal wellbores much more economical. Horizontal wellbores allow for far greater exposure to a formation than a conventional vertical wellbore. This is particularly useful in shale formations which do not have sufficient permeability to produce economically with a vertical well. Such wells when drilled onshore are now usually hydraulically fractured in a number of stages, especially in North America. The type of wellbore completion used will affect how many times the formation is fractured, and at what locations along the horizontal section of the wellbore.[81]

In North America, shale reservoirs such as the Bakken, Barnett, Montney, Haynesville, Marcellus, and most recently the Eagle Ford, Niobrara and Utica shales are drilled, completed and fractured using this method.[citation needed] The method by which the fractures are placed along the wellbore is most commonly achieved by one of two methods, known as "plug and perf" and "sliding sleeve".[82]

The wellbore for a plug and perf job is generally composed of standard joints of steel casing, either cemented or uncemented, which is set in place at the conclusion of the drilling process. Once the drilling rig has been removed, a wireline truck is used to perforate near the end of the well, following which a fracturing job is pumped (commonly called a stage). Once the stage is finished, the wireline truck will set a plug in the well to temporarily seal off that section, and then perforate the next section of the wellbore. Another stage is then pumped, and the process is repeated as necessary along the entire length of the horizontal part of the wellbore.[83]

The wellbore for the sliding sleeve technique is different in that the sliding sleeves are included at set spacings in the steel casing at the time it is set in place. The sliding sleeves are usually all closed at this time. When the well is ready to be fractured, using one of several activation techniques, the bottom sliding sleeve is opened and the first stage gets pumped. Once finished, the next sleeve is opened which concurrently isolates the first stage, and the process repeats. For the sliding sleeve method, wireline is usually not required.[citation needed]

These completion techniques may allow for more than 30 stages to be pumped into the horizontal section of a single well if required, which is far more than would typically be pumped into a vertical well.[84]

Economic effects

Hydraulic fracturing has been seen as one of the key methods of extracting unconventional oil and gas resources. According to the International Energy Agency, the remaining technically recoverable resources of shale gas are estimated to amount to 208 trillion cubic metres (208,000 km3), tight gas to 76 trillion cubic metres (76,000 km3), and coalbed methane to 47 trillion cubic metres (47,000 km3). As a rule, formations of these resources have lower permeability than conventional gas formations. Therefore depending on the geological characteristics of the formation, specific technologies (such as hydraulic fracturing) are required. Although there are also other methods to extract these resources, such as conventional drilling or horizontal drilling, hydraulic fracturing is one of the key methods making their extraction economically viable. The multi-stage fracturing technique has facilitated the development of shale gas and light tight oil production in the United States and is believed to do so in the other countries with unconventional hydrocarbon resources.[6]

The National Petroleum Council estimates that hydraulic fracturing will eventually account for nearly 70% of natural gas development in North America.[85] Hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling apply the latest technologies and make it commercially viable to recover shale gas and oil. In the United States, 45% of domestic natural gas production and 17% of oil production would be lost within 5 years without usage of hydraulic fracturing.[86]

A number of studies related to the economy and fracking, demonstrates a direct benefit to economies from fracking activities in the form of personnel, support, ancillary businesses, analysis and monitoring. Typically the funding source of the study is a focal point of controversy.[87] Most studies are either funded by mining companies or funded by environmental groups, which can at times lead to at least the appearance of unreliable studies.[87] A study was performed by Deller & Schreiber in 2012, looking at the relationship between non-oil and gas mining [dubious – discuss] and community economic growth. The study concluded that there is an effect on income growth; however, researchers found that mining does not lead to an increase in population or employment.[87] The actual financial effect of non-oil and gas mining on the economy is dependent on many variables and is difficult to identify definitively.

U.S.-based refineries have gained a competitive edge with their access to relatively inexpensive shale oil and Canadian crude. The U.S. is exporting more refined petroleum products, and also more liquified petroleum gas (LP gas). LP gas is produced from hydrocarbons called natural gas liquids, released by the hydraulic fracturing of petroliferous shale, in a variety of shale gas that's relatively easy to export. Propane, for example, costs around $620 a ton in the U.S. compared with more than $1,000 a ton in China, as of early 2014. Japan, for instance, is importing extra LP gas to fuel power plants, replacing idled nuclear plants. Trafigura Beheer BV, the third-largest independent trader of crude oil and refined products, said last month that "growth in U.S. shale production has turned the distillates market on its head." [88]

Environmental impact

Hydraulic fracturing has raised environmental concerns and is challenging the adequacy of existing regulatory regimes.[89] These concerns have included ground water contamination, risks to air quality, migration of gases and hydraulic fracturing chemicals to the surface, mishandling of waste, and the health effects of all these, as well as its contribution to raised atmospheric CO2 levels by enabling the extraction of previously sequestered hydrocarbons.[8][59][72] An additional concern is that oil obtained through hydraulic fracturing contains chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing, which may increase the rate at which rail tank cars and pipelines corrode, potentially releasing their load and its gases.[90][91]

Air

The air emissions from hydraulic fracturing are related to methane leaks originating from wells, and emissions from the diesel or natural gas powered equipment such as compressors, drilling rigs, pumps etc.[59] Also transportation of necessary water volume for hydraulic fracturing, if done by trucks, can cause high volumes of air emissions, especially particulate matter emissions.[92] There are also reports of health problems around compressors stations[93] or drilling sites,[94] although a causal relationship was not established for the limited number of wells studied[94] and another Texas government analysis found no evidence of effects.[95]

Whether natural gas produced by hydraulic fracturing causes higher well-to-burner emissions than gas produced from conventional wells is a matter of contention. Some studies have found that hydraulic fracturing has higher emissions due to gas released during completing wells as some gas returns to the surface, together with the fracturing fluids. Depending on their treatment, the well-to-burner emissions are 3.5%–12% higher than for conventional gas, but still and less than half the emissions of coal.[89][96] Methane leakage has been calculated at the rate of 1–7% with the United States Environmental Protection Agency's estimated leakage rate to be about 2.4%.[97][98]

Water

Water usage

Massive hydraulic fracturing uses traditionally between 1.2 and 3.5 million US gallons (4.5 and 13.2 Ml) of water per well, with large projects using up to 5 million US gallons (19 Ml). Additional water is used when wells are re-fractured.[66][99] An average well requires 3 to 8 million US gallons (11,000 to 30,000 m3) of water over its lifetime.[59][99][100][101] According to the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, greater volumes of fracturing fluids are required in Europe, where the shale depths average 1.5 times greater than in the U.S.[102]

Use of water for hydraulic fracturing can divert water from stream flow, water supplies for municipalities and industries such as power generation, as well as recreation and aquatic life.[103] The large volumes of water required for most common hydraulic fracturing methods have raised concerns for arid regions, such as Karoo in South Africa,[104] and in Pennsylvania,[105][106] and in drought-prone Texas, and Colorado in North America.[107]

Some producers have developed hydraulic fracturing techniques that could reduce the need for water by re-using recycled flowback water, or using carbon dioxide, liquid propane or other gases instead of water.[89][108][109] As hydraulic fracturing helps develop shale gas reserves which contributes to replacing coal usage with natural gas, by some data water saved by using natural gas combined cycle plants instead of coal steam turbine plants makes the overall water usage balance more positve.[110]

Injected fluid

There are concerns about possible contamination by hydraulic fracturing fluid both as it is injected under high pressure into the ground and as it returns to the surface.[111][112] To mitigate the effect of hydraulic fracturing on groundwater, the well and ideally the shale formation itself should remain hydraulically isolated from other geological formations, especially freshwater aquifers.[89]

The European Union regulatory regime requires full disclosure of all additives.[113] In the US, the Ground Water Protection Council launched FracFocus.org, an online voluntary disclosure database for hydraulic fracturing fluids funded by oil and gas trade groups and the U.S. Department of Energy.[114][115] While some of the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing are common and generally harmless, some additives used in the United States are known carcinogens.[72] Out of 2,500 hydraulic fracturing additives, more than 650 contained known or possible human carcinogens regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act or listed as hazardous air pollutants".[72] Another 2011 study identified 632 chemicals used in United States natural gas operations, of which only 353 are well-described in the scientific literature.[116]

Flowback

Estimates of the fluid that returns to the surface with the gas range from 15-20%[117] to 30–70%. Additional fluid may return to the surface through abandoned wells or other pathways.[118] After the flowback is recovered, formation water, usually brine, may continue to flow to the surface, requiring treatment or disposal. Approaches to managing these fluids, commonly known as flowback, produced water, or wastewater, include underground injection, municipal waste water treatment plants, industrial wastewater treatment, self-contained systems at well sites or fields, and recycling to fracture future wells.[96][119][120][121]

Methane

Groundwater methane contamination has adverse effect on water quality and in extreme cases may lead to potential explosion.[122][123] The correlation between drilling activity and methane pollution of the drinking water has been noted; however, studies to date have not established that methane contamination is caused by hydraulic fracturing itself, rather than by other well drilling or completion practices.[124] According to the 2011 study of the MIT Energy Initiative, "there is evidence of natural gas (methane) migration into freshwater zones in some areas, most likely as a result of substandard well completion practices i.e. poor quality cementing job or bad casing, by a few operators."[125] 2011 studies by the Colorado School of Public Health and Duke University also pointed to methane contamination stemming from the drilling process.[123][126] Most recent studies make use of tests that can distinguish between the deep thermogenic methane released during gas/oil drilling, and the shallower biogenic methane that can be released during water-well drilling. While both forms of methane result from decomposition, thermogenic methane results from geothermal assistance deeper underground.[127][126]

Radioactivity

In same cases hydraulic fracturing may dislodge uranium, radium, radon and thorium from formation and these substance may consist in flowback fluid.[128] Therefore there are concerns about the levels of radioactivity in wastewater from hydraulic fracturing and its potential impact on public health. Recycling this wastewater has been proposed as a partial solution, but this approach has limitations.[129]

Seismicity

Hydraulic fracturing routinely produces microseismic events much too small to be detected except by sensitive instruments. These microseismic events are often used to map the horizontal and vertical extent of the fracturing.[77] However, as of late 2012, there have been three instances of hydraulic fracturing, through induced seismicity, triggering quakes large enough to be felt by people: one each in the United States, Canada, and England.[9][130][131] The injection of waste water from oil and gas operations, including from hydraulic fracturing, into saltwater disposal wells may cause bigger low-magnitude tremors, being registered up to 3.3 (Mw).[132] Several earthquakes in 2011, including a 4.0 magnitude quake on New Year's Eve that hit Youngstown, Ohio, are likely linked to a disposal of hydraulic fracturing wastewater,[9] according to seismologists at Columbia University.[133] Although the magnitudes of these quakes has been small, the United States Geological Survey has said that there is no guarantee that larger quakes will not occur.[134] In addition, the frequency of the quakes has been increasing. In 2009, there were 50 earthquakes greater than magnitude 3.0 in the area spanning Alabama and Montana, and there were 87 quakes in 2010. In 2011 there were 134 earthquakes in the same area, a sixfold increase over 20th century levels.[135] There are also concerns that quakes may damage underground gas, oil, and water lines and wells that were not designed to withstand earthquakes.[134][136]

Health effects

Template:Globalize/US Concern has been expressed over the possible long and short term health effects of air and water contamination and radiation exposure by gas production.[128][137][138] Health consequences of concern include infertility, birth defects and cancer.[139][140][141]

A study conducted in Garfield County, Colorado and published in Endocrinology suggested that natural gas drilling operations may result in elevated endocrine-disrupting chemical activity in surface and ground water.[140]

A 2012 study concluded that risk prevention efforts should be directed towards reducing air emission exposures for persons living and working near wells during well completions.[142]

Public debate

Politics and public policy

To control the hydraulic fracturing industry, some governments are developing legislation and some municipalities are developing local zoning limitations.[143] In 2011, France became the first nation to ban hydraulic fracturing.[11][12] Some other countries have placed a temporary moratorium on the practice.[144] The US has the longest history with hydraulic fracturing, so its approach to hydraulic fracturing may be modeled by other countries.[104] In August 2013 the Church of England, in an official statement, criticized those who advocate “blanket opposition” to fracking.[145]

The considerable opposition against hydraulic fracturing activities in local townships has led companies to adopt a variety of public relations measures to assuage fears about hydraulic fracturing, including the admitted use of "military tactics to counter drilling opponents". At a conference where public relations measures were discussed, a senior executive at Anadarko Petroleum was recorded on tape saying, "Download the US Army / Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Manual, because we are dealing with an insurgency", while referring to hydraulic fracturing opponents. Matt Pitzarella, spokesman for Range Resources also told other conference attendees that Range employed psychological warfare operations veterans. According to Pitzarella, the experience learned in the Middle East has been valuable to Range Resources in Pennsylvania, when dealing with emotionally charged township meetings and advising townships on zoning and local ordinances dealing with hydraulic fracturing.[146][147]

Police officers have recently been forced, however, to deal with intentionally disruptive and even potentially violent opposition to oil and gas development. In March 2013, ten people were arrested[148] during an "anti-fracking protest" near New Matamoras, Ohio, after they illegally entered a development zone and latched themselves to drilling equipment. In northwest Pennsylvania, there was a drive-by shooting at a well site, in which an individual shot two rounds of a small-caliber rifle in the direction of a drilling rig, just before shouting profanities at the site and fleeing the scene.[149] And in Washington County, Pa., a contractor working on a gas pipeline found a pipe bomb that had been placed where a pipeline was to be constructed, which local authorities said would have caused a “catastrophe” had they not discovered and detonated it.[150]

Media coverage

Josh Fox's 2010 Academy Award nominated film Gasland [151] became a center of opposition to hydraulic fracturing of shale. The movie presented problems with ground water contamination near well sites in Pennsylvania, Wyoming, and Colorado.[152] Energy in Depth, an oil and gas industry lobbying group, called the film's facts into question.[153] In response, a rebuttal of Energy in Depth's claims of inaccuracy was refuted on Gasland's website.[154]

The Director of the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) offered to be interviewed as part of the film if he could review what was included from the interview in the final film but Fox declined the offer.[155] Exxon Mobil, Chevron Corporation and ConocoPhillips aired advertisements during 2011 and 2012 that claimed to describe the economic and environmental benefits of natural gas and argue that hydraulic fracturing was safe.[156]

The film Promised Land, starring Matt Damon, takes on hydraulic fracturing.[157] The gas industry is making plans to try to counter the film's criticisms of hydraulic fracturing with informational flyers, and Twitter and Facebook posts.[156]

On January 22, 2013 Northern Irish journalist and filmmaker Phelim McAleer released a crowdfunded[158] documentary called FrackNation as a response to the claims made by Fox in Gasland. FrackNation premiered on Mark Cuban's AXS TV. The premiere corresponded with the release of Promised Land.[159]

Research issues

Concerns have been raised about research financed by foundations and corporations[160] that some have argued is designed to inflate or minimize the risks of development,[161] as well as lobbying by the gas industry to promote its activities.[162] Several organizations, researchers, and media outlets have reported difficulty in conducting and reporting the results of studies on hydraulic fracturing due to industry[163][164] and governmental pressure,[10] and expressed concern over possible censoring of environmental reports.[163][165][166] Researchers have recommended requiring disclosure of all hydraulic fracturing fluids, testing animals raised near fracturing sites, and closer monitoring of environmental samples.[167] Many believe there is a need for more research into the environmental and health effects of the technique.[168][169]

See also

- Hydraulic fracturing by country

- Hydraulic fracturing in the United States

- Hydraulic fracturing in the United Kingdom

- In-situ leach

- Directional drilling

- Environmental concerns with electricity generation

- Environmental impact of petroleum

- Environmental impact of the oil shale industry

- ExxonMobil Electrofrac

References

- ^ Lubber, Mindy (28 May 2013). "Escalating Water Strains In Fracking Regions". Forbes. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ a b Charlez, Philippe A. (1997). Rock Mechanics: Petroleum Applications. Paris: Editions Technip. p. 239. ISBN 9782710805861. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ "Fracking legislation, California", The LA times (editorial), 26 May 2013

- ^ King, George E (2012), Hydraulic fracturing 101 (PDF), Society of Petroleum Engineers, Paper 152596

- ^ Staff. "State by state maps of hydraulic fracturing in US". Fractracker.org. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ a b IEA (29 May 2012). Golden Rules for a Golden Age of Gas. World Energy Outlook Special Report on Unconventional Gas (PDF). OECD. pp. 18–27.

- ^ Hillard Huntington et al EMF 26: Changing the Game? Emissions and Market Implications of New Natural Gas Supplies Report. Stanford University. Energy Modeling Forum, 2013.

- ^ a b Brown, Valerie J. (February 2007). "Industry Issues: Putting the Heat on Gas". Environmental Health Perspectives. 115 (2). US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences: A76. doi:10.1289/ehp.115-a76. PMC 1817691. PMID 17384744. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- ^ a b c Kim, Won-Young 'Induced seismicity associated with fluid injection into a deep well in Youngstown, Ohio', Journal of Geophysical Research-Solid Earth

- ^ a b Jared Metzker (7 August 2013). "Govt, Energy Industry Accused of Suppressing Fracking Dangers". Inter Press Service. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ a b Patel, Tara (31 March 2011). "The French Public Says No to 'Le Fracking'". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ a b Patel, Tara (4 October 2011). "France to Keep Fracking Ban to Protect Environment, Sarkozy Says". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Fjaer, E. (2008). "Mechanics of hydraulic fracturing". Petroleum related rock mechanics. Developments in petroleum science (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 369. ISBN 978-0-444-50260-5. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Price, N. J.; Cosgrove, J. W. (1990). Analysis of geological structures. Cambridge University Press. pp. 30–33. ISBN 978-0-521-31958-4. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Manthei, G.; Eisenblätter, J.; Kamlot, P. (2003). "Stress measurement in salt mines using a special hydraulic fracturing borehole tool". In Natau, Fecker & Pimentel (ed.). Geotechnical Measurements and Modelling (PDF). pp. 355–360. ISBN 90-5809-603-3. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ^ Zoback, M.D. (2007). Reservoir geomechanics. Cambridge University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780521146197. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ^ Laubach, S. E.; Reed, R. M.; Olson, J. E.; Lander, R. H.; Bonnell, L. M. (2004). "Coevolution of crack-seal texture and fracture porosity in sedimentary rocks: cathodoluminescence observations of regional fractures". Journal of Structural Geology. 26 (5). Elsevier: 967–982. Bibcode:2004JSG....26..967L. doi:10.1016/j.jsg.2003.08.019. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Sibson, R. H.; Moore, J.; Rankin, A. H. (1975). "Seismic pumping--a hydrothermal fluid transport mechanism". Journal of the Geological Society. 131 (6). London: Geological Society: 653–659. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.131.6.0653. (subscription required). Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ Gill, R. (2010). Igneous rocks and processes: a practical guide. John Wiley and Sons. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-4443-3065-6. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- ^ "Acid fracturing"

- ^ a b Montgomery, Carl T.; Smith, Michael B. (December 2010). "Hydraulic fracturing. History of an enduring technology" (PDF). JPT Online. Society of Petroleum Engineers: 26–41. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- ^ Energy Institute (February 2012). Fact-Based Regulation for Environmental Protection in Shale Gas Development (PDF) (Report). University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ A. J. Stark, A. Settari, J. R. Jones, Analysis of Hydraulic Fracturing of High Permeability Gas Wells to Reduce Non-darcy Skin Effects, Petroleum Society of Canada, Annual Technical Meeting, Jun 8 - 10, 1998, Calgary, Alberta.[dead link]

- ^ a b Mader, Detlef (1989). Hydraulic Proppant Fracturing and Gravel Packing. Elsevier. pp. 173–174, 202. ISBN 9780444873521.

- ^ a b c Ben E. Law and Charles W. Spencer, 1993, "Gas in tight reservoirs-an emerging major source of energy," in David G. Howell (ed.), The Future of Energy Gasses, US Geological Survey, Professional Paper 1570, p.233-252.

- ^ C.R. Fast, G.B. Holman, and R. J. Covlin, "The application of massive hydraulic fracturing to the tight Muddy 'J' Formation, Wattenberg Field, Colorado," in Harry K. Veal, (ed.), Exploration Frontiers of the Central and Southern Rockies (Denver: Rocky Mountain Association of Geologists, 1977) 293-300.

- ^ Robert Chancellor, "Mesaverde hydraulic fracture stimulation, northern Piceance Basin - progress report," in Harry K. Veal, (ed.), Exploration Frontiers of the Central and Southern Rockies (Denver: Rocky Mountain Association of Geologists, 1977) 285-291.

- ^ C.E> Bell and others, Effective diverting in horizontal wells in the Austin Chalk, Society of Petroleum Engineers conference paper, 1993.[dead link]

- ^ a b c Robbins K. (2013). Awakening the Slumbering Giant: How Horizontal Drilling Technology Brought the Endangered Species Act to Bear on Hydraulic Fracturing. Case Western Reserve Law Review.

- ^ US Dept. of Energy, How is shale gas produced?, Apr. 2013.

- ^ United States National Research Council, Committee to Review the Gas Research Institute's Research, Development and Demonstration Program, Gas Research Institute (1989). A review of the management of the Gas Research Institute. National Academies. p. ?.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "US Government Role in Shale Gas Fracking: An Overview"

- ^ SPE production & operations. Vol. 20. Society of Petroleum Engineers. 2005. p. 87.

- ^ The Breakthrough Institute. Interview with Dan Steward, former Mitchell Energy Vice President. December 2011.

- ^ Zuckerman, Gregory. "How fracking billionaires built their empires". Quartz. The Atlantic Media Company. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ Wasley, Andrew (1 March 2013) On the frontline of Poland's fracking rush The Guardian, Retrieved 3 March 2013

- ^ (7 August 2012) JKX Awards Fracking Contract for Ukrainian Prospect Natural Gas Europe, Retrieved 3 March 2013

- ^ (18 February 2013) Turkey's shale gas hopes draw growing interest Reuters, Retrieved 3 March 2013

- ^ Bakewell, Sally (13 December 2012). "U.K. Government Lifts Ban on Shale Gas Fracking". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "Commission recommendation on minimum principles for the exploration and production of hydrocarbons (such as shale gas) using high-volume hydraulic fracturing (2014/70/EU)". Official Journal of the European Union. 22 January 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ^ "Hydraulic fracturing research study" (PDF). EPA. June 2010. EPA/600/F-10/002. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ^ "The Barnett Shale" (PDF). North Keller Neighbors Together. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ David Wethe (19 January 2012). "Like Fracking? You'll Love 'Super Fracking'". Businessweek. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ "Production Decline of a Natural Gas Well Over Time". Geology.com. The Geology Society of America. 3 January 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ Gidley, John L. (1989). Recent Advances in Hydraulic Fracturing. SPE Monograph. Vol. 12. SPE. p. ?. ISBN 9781555630201.

- ^ Ching H. Yew (1997). Mechanics of Hydraulic Fracturing. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. ?. ISBN 9780884154747.

- ^ a b Economides, Michael J. (2000). Reservoir stimulation. J. Wiley. p. P-2. ISBN 9780471491927.

- ^ Banks, David; Odling, N. E.; Skarphagen, H.; Rohr-Torp, E. (May 1996). "Permeability and stress in crystalline rocks". Terra Nova. 8 (3): 223–235. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3121.1996.tb00751.x.

- ^ Brown, Edwin Thomas (2007) [2003]. Block Caving Geomechanics (2nd ed.). Indooroopilly, Queensland: Julius Kruttschnitt Mineral Research Centre, UQ. ISBN 978-0-9803622-0-6. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Frank, U.; Barkley, N. (February 1995). "Soil Remediation: Application of Innovative and Standard Technologies". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 40 (2): 191–201. doi:10.1016/0304-3894(94)00069-S. ISSN 0304-3894.

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help) (subscription required) - ^ Bell, Frederic Gladstone (2004). Engineering Geology and Construction. Taylor & Francis. p. 670. ISBN 9780415259392.

- ^ Aamodt, R. Lee; Kuriyagawa, Michio (1983). "Measurement of Instantaneous Shut-In Pressure in Crystalline Rock". Hydraulic fracturing stress measurements. National Academies. p. 139.

- ^ "Geothermal Technologies Program: How an Enhanced Geothermal System Works". eere.energy.gov. 16 February 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Miller, Bruce G. (2005). Coal Energy Systems. Sustainable World Series. Academic Press. p. 380. ISBN 9780124974517.

- ^ Waltz, James; Decker, Tim L (1981), "Hydro-fracturing offers many benefits", Johnson Driller's Journal (2nd quarter): 4–9

- ^ Williamson, WH (1982), "The use of hydraulic techniques to improve the yield of bores in fractured rocks", Groundwater in Fractured Rock, Conference Series, Australian Water Resources Council

- ^ Less, C; Andersen, N (February 1994), "Hydrofracture: state of the art in South Africa", Applied Hydrogeology: 59–63

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ground Water Protection Council; ALL Consulting (April 2009). Modern Shale Gas Development in the United States: A Primer (PDF) (Report). DOE Office of Fossil Energy and National Energy Technology Laboratory. pp. 56–66. DE-FG26-04NT15455. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Penny, Glenn S.; Conway, Michael W.; Lee, Wellington (June 1985). "Control and Modeling of Fluid Leakoff During Hydraulic Fracturing". Journal of Petroleum Technology. 37 (6). Society of Petroleum Engineers: 1071–1081. doi:10.2118/12486-PA. Retrieved 10 May 2012.[dead link]

- ^ Arthur, J. Daniel; Bohm, Brian; Coughlin, Bobbi Jo; Layne, Mark (2008). Hydraulic Fracturing Considerations for Natural Gas Wells of the Fayetteville Shale (PDF) (Report). ALL Consulting. p. 10. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ Chilingar, George V.; Robertson, John O.; Kumar, Sanjay (1989). Surface Operations in Petroleum Production. Vol. 2. Elsevier. pp. 143–152. ISBN 9780444426772.

- ^ Love, Adam H. (December 2005). "Fracking: The Controversy Over its Safety for the Environment". Johnson Wright, Inc. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ "Hydraulic Fracturing". University of Colorado Law School. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ Wan Renpu (2011). Advanced Well Completion Engineering. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 424. ISBN 9780123858689.

- ^ a b c d e Andrews, Anthony; et al. (30 October 2009). Unconventional Gas Shales: Development, Technology, and Policy Issues (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service. pp. 7, 23. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

{{cite report}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Ram Narayan (8 August 2012). "From Food to Fracking: Guar Gum and International Regulation". RegBlog. University of Pennsylvania Law School. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Hartnett-White, K. (2011). "The Fracas About Fracking- Low Risk, High Reward, but the EPA is Against it" (PDF). National Review Online. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Freeing Up Energy. Hydraulic Fracturing: Unlocking America's Natural Gas Resources" (PDF). American Petroleum Institute. 19 July 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Brainard, Curtis (June 2013). "The Future of Energy". Popular Science Magazine. p. 59. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "CARBO ceramics". Retrieved 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c d Chemicals Used in Hydraulic Fracturing (PDF) (Report). Committee on Energy and Commerce U.S. House of Representatives. 18 April 2011. p. ?.

- ^ a b ALL Consulting (June 2012). The Modern Practices of Hydraulic Fracturing: A Focus on Canadian Resources (PDF) (Report). Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ Reis, John C. (1976). Environmental Control in Petroleum Engineering. Gulf Professional Publishers.

- ^ a b c Radiation Protection and the Management of Radioactive Waste in the Oil and Gas Industry (PDF) (Report). International Atomic Energy Agency. 2003. pp. 39–40. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

Beta emitters, including 3H and 14C, may be used when it is feasible to use sampling techniques to detect the presence of the radiotracer, or when changes in activity concentration can be used as indicators of the properties of interest in the system. Gamma emitters, such as 46Sc, 140La, 56Mn, 24Na, 124Sb, 192Ir, 99Tcm, 131I, 110Agm, 41Ar and 133Xe are used extensively because of the ease with which they can be identified and measured. ... In order to aid the detection of any spillage of solutions of the 'soft' beta emitters, they are sometimes spiked with a short half-life gamma emitter such as 82Br

- ^ a b Jack E. Whitten, Steven R. Courtemanche, Andrea R. Jones, Richard E. Penrod, and David B. Fogl (Division of Industrial and Medical Nuclear Safety, Office of Nuclear Material Safety and Safeguards) (June 2000). "Consolidated Guidance About Materials Licenses: Program-Specific Guidance About Well Logging, Tracer, and Field Flood Study Licenses (NUREG-1556, Volume 14)". US Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

labeled Frac Sand...Sc-46, Br-82, Ag-110m, Sb-124, Ir-192

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Bennet, Les; et al. "The Source for Hydraulic Fracture Characterization" (PDF). Oilfield Review (Winter 2005/2006). Schlumberger: 42–57. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Fehler, Michael C. (1989). "Stress Control of seismicity patterns observed during hydraulic fracturing experiments at the Fenton Hill hot dry rock geothermal energy site, New Mexico". International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences & Geomechanics Abstracts. 3. 26. doi:10.1016/0148-9062(89)91971-2. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Le Calvez, Joel (2007). "Real-time microseismic monitoring of hydraulic fracture treatment: A tool to improve completion and reservoir management". SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technology Conference.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Cipolla, Craig (2010). "Hydraulic Fracture Monitoring to Reservoir Simulation: Maximizing Value". SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Seale, Rocky (July/August 2007). "Open hole completion systems enables multi-stage fracturing and stimulation along horizontal wellbores" (PDF). Drilling Contractor (Fracturing stimulation ed.). Retrieved October 1, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Completion Technologies". EERC. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ "Energy from Shale". 2011.

- ^ Mooney, Chris (2011). "The Truth About Fracking". Scientific American. 305 (305): 80–85. Bibcode:2011SciAm.305d..80M. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1111-80.

- ^ National Petroleum Council, Prudent Development: Realizing the Potential of North America’s Abundant Natural Gas and Oil Resources, September 15, 2011.

- ^ IHS Global Insight, Measuring the Economic and Energy Impacts of Proposals to Regulate Hydraulic Fracturing, 2009.

- ^ a b c Deller, Steven; Schreiber, Andrew (2012). "Mining and Community Economic Growth". The Review of Regional Studies. pp. 121–141. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

The results presented here suggest that a higher level of dependency on nonoil-and-gas–based mining, such as frack sand mining or other mineral mining, does not lead to higher levels of population and employment growth, but does have a positive impact on income growth. Indeed, we find that mining may have a detrimental impact on population growth...

- ^ Asian Refiners Get Squeezed by U.S. Energy Boom, Wall Street Journal, Jan. 1, 2014

- ^ a b c d IEA (2011). World Energy Outlook 2011. OECD. pp. 91, 164. ISBN 9789264124134.

- ^ Jim Efstathiou Jr. and Angela Greiling Keane (13 August 2013). "North Dakota Oil Boom Seen Adding Costs for Rail Safety". Bloomberg. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ Gebrekidan, Selam (11 October 2013). "Corrosion may have led to North Dakota pipeline leak: regulator". Reuters. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ Fernandez, John Michael; Gunter, Matthew. "Hydraulic Fracturing: Environmentally Friendly Practices" (PDF). Houston Advanced Research Center. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Biello, David (30 March 2010). "Natural gas cracked out of shale deposits may mean the U.S. has a stable supply for a century – but at what cost to the environment and human health?". Scientific American. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ a b Schmidt, Charles (1 August 2011). "Blind Rush? Shale Gas Boom Proceeds Amid Human Health Questions". Environmental Health Perspectives. 119 (8): a348–a353. doi:10.1289/ehp.119-a348. PMC 3237379.

- ^ "DISH, TExas Exposure Investigation" (PDF). Texas DSHS. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ a b Logan, Jeffrey (2012). Natural Gas and the Transformation of the U.S. Energy Sector: Electricity (PDF) (Report). Joint Institute for Strategic Energy Analysis. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ "The Importance of Accurate Data". True Blue Natural Gas. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Allen, David T.; Torres, Vincent N.; Thomas, James; Sullivan, David W.; Harrison, Matthew; Hendler, Al; Herndon, Scott C.; Kolb, Charles E.; Fraser, Matthew P.; Hill, A. Daniel; Lamb, Brian K.; Miskimins, Jennifer; Sawyer, Robert F.; Seinfeld, John H. (16 September 2013). "Measurements of methane emissions at natural gas production sites in the United States" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi:10.1073/pnas.1304880110. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ^ a b Abdalla, Charles W.; Drohan, Joy R. (2010). Water Withdrawals for Development of Marcellus Shale Gas in Pennsylvania. Introduction to Pennsylvania’s Water Resources (PDF) (Report). The Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

Hydrofracturing a horizontal Marcellus well may use 4 to 8 million gallons of water, typically within about 1 week. However, based on experiences in other major U.S. shale gas fields, some Marcellus wells may need to be hydrofractured several times over their productive life (typically five to twenty years or more)

- ^ Arthur, J. Daniel; Uretsky, Mike; Wilson, Preston (5–6 May 2010). Water Resources and Use for Hydraulic Fracturing in the Marcellus Shale Region (PDF). Meeting of the American Institute of Professional Geologists. Pittsburgh: ALL Consulting. p. 3. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ Cothren, Jackson. Modeling the Effects of Non-Riparian Surface Water Diversions on Flow Conditions in the Little Red Watershed (PDF) (Report). U. S. Geological Survey, Arkansas Water Science Center Arkansas Water Resources Center, American Water Resources Association, Arkansas State Section Fayetteville Shale Symposium 2012. p. 12. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

...each well requires between 3 and 7 million gallons of water for hydraulic fracturing and the number of wells is expected to grow in the future

- ^ Faucon, Benoît (17 September 2012). "Shale-Gas Boom Hits Eastern Europe". WSJ.com. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ John Upton (15 August 2013). "Fracking company wants to build new pipeline — for water". Grist. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ a b Urbina, Ian (30 December 2011). "Hunt for Gas Hits Fragile Soil, and South Africans Fear Risks". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

Covering much of the roughly 800 miles between Johannesburg and Cape Town, this arid expanse – its name [Karoo] means "thirsty land" – sees less rain in some parts than the Mojave Desert.

- ^ Janco, David F. (3 January 2008). PADEP Determination Letter No. 352 Determination Letter acquired by the Scranton Times-Tribune via Right-To-Know Law request. Order: Atlas Miller 42 and 43 gas wells; Aug 2007 investigation; supplied temporary buffalo for two springs, ordered to permanently replace supplies (PDF) (Report). Scranton Times-Tribune. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ Janco, David F. (1 February 2007). PADEP Determination Letter No. 970. Diminution of Snow Shoe Borough Authority Water Well No. 2; primary water source for about 1,000 homes and businesses in and around the borough; contested by Range Resources. Determination Letter acquired by the Scranton Times-Tribune via Right-To-Know Law request (PDF) (Report). Scranton Times-Tribune. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ Staff (16 June 2013). "Fracking fuels water battles". Politico. Associated Press. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ Texas Water Report: Going Deeper for the Solution Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts. Retrieved 2/11/14.

- ^ "Skipping the Water in Fracking."

- ^ Drought and the water–energy nexus in Texas Environmental Research Letters. Retrieved 2/11/14.

- ^ "Drilling Down: Documents: Natural Gas's Toxic Waste". The New York Times. 26 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ Ehrenburg, Rachel (25 June 2013). "News in Brief: High methane in drinking water near fracking sites. Well construction and geology may both play a role". Science News. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ Dave Healy (July 2012). /sss/UniAberdeen_FrackingReport.pdf Hydraulic Fracturing or ‘Fracking’: A Short Summary of Current Knowledge and Potential Environmental Impacts A Small Scale Study for the Environmental Protection Agency (Ireland) under the Science, Technology, Research & Innovation for the Environment. (STRIVE) Programme 2007 (PDF) (Report). Environmental Protection Agency, Ireland. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

{{cite report}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Hass, Benjamin (14 August 2012). "Fracking Hazards Obscured in Failure to Disclose Wells". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Soraghan, Mike (13 December 2013). "White House official backs FracFocus as preferred disclosure method". E&E News. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Colborn, Theo; Kwiatkowski, Carol; Schultz, Kim; Bachran, Mary (2011). "Natural Gas Operations from a Public Health Perspective" (PDF). Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: an International Journal. 17 (5). Taylor & Francis: 1039–1056. doi:10.1080/10807039.2011.605662.

- ^ Staff. Waste water (Flowback)from Hydraulic Fracturing (PDF) (Report). Ohio Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

Most of the water used in fracturing remains thousands of feet underground, however, about 15-20 percent returns to the surface through a steel-cased well bore and is temporarily stored in steel tanks or lined pits. The wastewater which returns to the surface after hydraulic fracturing is called flowback

- ^ Detrow, Scott (9 October 2012). "Perilous Pathways: How Drilling Near An Abandoned Well Produced a Methane Geyser". StateImpact Pennsylvania. NPR. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

As Shell was drilling and then hydraulically fracturing its nearby well, the activity displaced shallow pockets of natural gas — possibly some of the same pockets the Morris Run Coal company ran into in 1932. The gas disturbed by Shell's drilling moved underground until it found its way to the Butters well, and then shot up to the surface. Companies have been extracting oil and gas from Pennsylvania's subsurface since 1859, when Edwin Drake drilled the world's first commercial oil well. Over that 150-year timespan, as many as 300,000 wells have been drilled, an unknown number of them left behind as hidden holes in the ground. Nobody knows how many because most of those wells were drilled long before Pennsylvania required permits, record-keeping or any kind of regulation. It's rare for a modern drilling operation to intersect — the technical term is "communicate" — with an abandoned well. But incidents like Shell's Tioga County geyser are a reminder of the dangers these many unplotted holes in the ground can cause when Marcellus or Utica Shale wells are drilled nearby. And while state regulators are considering requiring energy companies to survey abandoned wells within a 1,000-foot radius of new drilling operations, the location of nearby wells is currently missing from the permitting process. That's the case in nearly every state where natural gas drillers are setting up hydraulic fracturing operations in regions with long drilling histories. Regulators don't require drillers to search for abandoned wells and plug them because, the thinking goes, this is something drillers are doing anyway.

{{cite web}}: soft hyphen character in|work=at position 17 (help) - ^ Arthur, J. Daniel; Langhus, Bruce; Alleman, David (2008). An overview of modern shale gas development in the United States (PDF) (Report). ALL Consulting. p. 21. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ Hopey, Don (1 March 2011). "Gas drillers recycling more water, using fewer chemicals". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Litvak, Anya (21 August 2012). "Marcellus flowback recycling reaches 90 percent in SWPA". Pittsburgh Business Times. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- ^ Urbina, Ian (26 February 2011). "Regulation Lax as Gas Wells' Tainted Water Hits Rivers". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ a b Osborn, Stephen G.; Vengosh, Avner; Warner, Nathaniel R.; Jackson, Robert B. (17 May 2011). "Methane contamination of drinking water accompanying gas-well drilling and hydraulic fracturing" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (20): 8172–8176. doi:10.1073/pnas.1100682108. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ "Duke Study finds Methane gas in well water near fracking sites" May 9, 2011 Philly Inquirer

- ^ Moniz, Ernest J.; et al. (June 2011). The Future of Natural Gas: An Interdisciplinary MIT Study (PDF) (Report). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

{{cite report}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b "Gasland Correction Document" (PDF). Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ Molofsky, L. J.; Connor, J. A.; Shahla, K. F.; Wylie, A. S.; Wagner, T. (5 December 2011). "Methane in Pennsylvania Water Wells Unrelated to Marcellus Shale Fracturing". Oil and Gas Journal. 109 (49). Pennwell Corporation: 54–67.

- ^ a b Weinhold, Bob (19 September 2012). "Unknown Quantity: Regulating Radionuclides in Tap Water". Environmental Health Perspectives. NIEHS, NIH. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

Examples of human activities that may lead to radionuclide exposure include mining, milling, and processing of radioactive substances; wastewater releases from the hydraulic fracturing of oil and natural gas wells... Mining and hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking", can concentrate levels of uranium (as well as radium, radon, and thorium) in wastewater...

{{cite web}}: soft hyphen character in|quote=at position 117 (help) - ^ Urbina, Ian (1 March 2011). "Drilling Down: Wastewater Recycling No Cure-All in Gas Process". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "How is hydraulic fracturing related to earthquakes and tremors?". USGS. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ Begley, Sharon; McAllister, Edward (12 July 2013). "News in Science: Earthquakes may trigger fracking tremors". ABC Science. Reuters. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Zoback, Mark; Kitasei, Saya; Copithorne, Brad (July 2010). Addressing the Environmental Risks from Shale Gas Development (PDF) (Report). Worldwatch Institute. p. 9. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Ohio Quakes Probably Triggered by Waste Disposal Well, Say Seismologists" (Press release). Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory. 6 January 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ a b Rachel Maddow, Terrence Henry (7 August 2012). Rachel Maddow Show: Fracking waste messes with Texas (video). MSNBC. Event occurs at 9:24 - 10:35.

{{cite AV media}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Soraghan, Mike (29 March 2012). "'Remarkable' spate of man-made quakes linked to drilling, USGS team says". EnergyWire. E&E. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ Henry, Terrence (6 August 2012). "How Fracking Disposal Wells Are Causing Earthquakes in Dallas-Fort Worth". State Impact Texas. NPR. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ^ McHaney, Sarah (21 October 2012). "Shale Gas Extraction Brings Local Health Impacts". IPS News. Inter Press Service. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ Colborn, Theo; Kwiatkowski, Carol; Schultz, Kim; Bachran, Mary (2011). "Natural gas operations from public health perspective". Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: an International Journal. 17 (5): 1039–1056. doi:10.1080/10807039.2011.605662.

- ^ Banerjee, Neela (16 December 2013). "Hormone-disrupting chemicals found in water at fracking sites. A study of hydraulic fracturing sites in Colorado finds substances that have been linked to infertility, birth defects and cancer". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ a b Kassotis, Christopher D.; Tillitt, Donald E.; Davis, J. Wade; Hormann, Annette M.; Nagel, Susan C. (March 2014). "Estrogen and Androgen Receptor Activities of Hydraulic Fracturing Chemicals and Surface and Ground Water in a Drilling-Dense Region". Endocrinology. 155 (3). doi:10.1210/en.2013-1697. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ McMahon, Jeff (24 July 2013). "Strange Byproduct Of Fracking Boom: Radioactive Socks". Forbes. Retrieved 28 July 2013.