OPEC

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| |

| Headquarters | Vienna, Austria |

| Official language | English[1] |

| Type | Cartel |

| Membership | |

| Leaders | |

• President | Diezani Alison-Madueke |

| Abdallah el-Badri | |

| Establishment | Baghdad, Iraq |

• Statute | 10–14 September 1960 |

• in effect | January 1961 |

| Area | |

• Total | 11,854,977 km2 (4,577,232 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 372,368,429 |

• Density | 31.16/km2 (80.7/sq mi) |

| Currency | Indexed as USD -per-barrel |

Website www.OPEC.org | |

Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC, /ˈoʊpɛk/ OH-pek), a permanent, international organization headquartered in Vienna, Austria, was established in Baghdad, Iraq on 10–14 September 1960.[2] Its mandate is to "coordinate and unify the petroleum policies" of its members and to "ensure the stabilization of oil markets in order to secure an efficient, economic and regular supply of petroleum to consumers, a steady income to producers, and a fair return on capital for those investing in the petroleum industry."[3][4][5][6] In 2014 OPEC comprised twelve members: Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Venezuela.[2] According to the United States Energy Information Administration (EIA), OPEC crude oil production is an important factor affecting global oil prices. OPEC sets production targets for its member nations and generally, when OPEC production targets are reduced, oil prices increase.[7] Projections of changes in Saudi production result in changes in the price of benchmark crude oils.[7]

OPEC was formed in 1960 when the international oil market was largely dominated by a group of multinational companies known as the 'seven sisters'.[8]: 503 The formation of OPEC represented a collective act of sovereignty by oil exporting nations, and marked a turning point in state control over natural resources.[8]: 505 In the 1960s OPEC ensured that oil companies could not unilaterally cut prices.[8]: 505 In December 2014, OPEC and the oil men were named in the top 10 most influential people in the shipping industry by Lloyds.[9]

Decision making

The OPEC Conference is the supreme authority of the Organization, and consists of delegations normally headed by the Ministers of Oil, Mines and Energy of member Countries. The Conference usually meets twice a year (in March and September) and in extraordinary sessions whenever required. It operates on the principle of unanimity, and one member, one vote.[10]

Crude oil benchmarks

Crude oil benchmark is a crude oil that serves as a reference price for buyers and sellers of crude oil.

OPEC Reference Basket of Crudes

OPEC Reference Basket of Crudes, a weighted average of prices for petroleum blends — Saharan Blend (Algeria), Girassol (Angola), Oriente (Ecuador), Iran Heavy (Islamic Republic of Iran), Basra Light (Iraq), Kuwait Export (Kuwait), Es Sider (Libya), Bonny Light (Nigeria), Qatar Marine (Qatar), Arab Light (Saudi Arabia), Murban (UAE) and Merey (Venezuela)— is an important benchmark for crude oil prices.[11]

North Sea Brent crude oil is the benchmark for half of global oil trade and the leading global price benchmark for Atlantic basin crude oils.[12] It is used to price two thirds of the world's internationally traded crude oil supplies.

The other well-known classifications or benchmarks are West Texas Intermediate (WTI), Dubai Crude, Oman Crude and Urals oil.

Global market 2014

According to the New York Times the oil-drilling boom in the United States has increased oil production by over 70 percent since 2008 and has reduced the United States oil imports from OPEC by fifty per cent.[13]

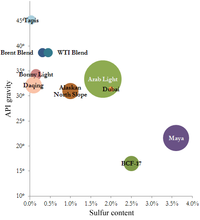

Since 2011 the United States absorbed the rapidly increased domestic production of sweet, light, tight oil by reducing like-for-like or similar grade, imported crude oil[14] from Nigerian and other African suppliers.[13] From 2011 to 2013 fifty per cent of oil import reductions impacted light crude (API gravity 35+).[15] Almost 96 per cent of the 1.8 million barrels per day (290,000 m3/d) of its growth comes from light, sweet crude from tight resource formations.[14] As domestic production continues to increase, the U.S. is facing future challenges of absorbing the light, sweet tight oil.[15]

In 2011 the United States imported 1.7 million barrels per day (270,000 m3/d). By 2013 crude oil imports were reduced to 1.0 million barrels per day (160,000 m3/d).[15] In January and February 2014, light crude imports to the United States averaged only 0.6 million barrels per day (95,000 m3/d).[15]

In July 2014 the non-OPEC production was predicted at 1.7 million barrels per day (270,000 m3/d) with the United States and Canada producing 1.6 million barrels per day (250,000 m3/d) in 2014.[16]

In June 2014 crude oil prices abruptly dropped by about a third as U.S. shale oil production increased and China and Europe's demand for oil decreased. Just before the United States rapidly backed out of the crude oil import market because of booming national production, the spot price of North Sea Brent crude oil peaked on 17 June 2014 at more than US$115 per barrel.[12]

Nigeria is the largest producer of sweet oil in OPEC. By July 2014, as the US stopped importing light sweet crude, more crude oil became available to refineries in China, India, Japan and South Korea. They collectively purchased 42% more Nigerian crude in 2014 compared with 2013. Starting in June 2014 Saudi Aramco—Saudi Arabia's national oil and gas company and the world's largest oil company in terms of production—discounted the price of its crude to Asian refineries[17] to compete with oil from Nigerian and other African suppliers.[13]

In their press release 27 November 2014 at the OPEC Conference in Vienna, it was announced that the 'OECD-Americas' was the main non-OPEC oil supply contributor to an anticipated supply growth of 1.4 million barrels per day (220,000 m3/d) to average 57.3 million barrels per day (9,110,000 m3/d) in 2015. From 2011 until mid-June 2014 the annual average price of oil was about US$110 per barrel. Since June 2014 however, the price of oil slid to $US80. OPEC argued that this drop in the price of oil was not exclusively "attributed to oil market fundamentals." While oil market fundamentals, "ample supply, moderate demand, a stronger US dollar and uncertainties about global economic growth" contributed to the drop in price, "speculative activity in the oil market has also been an important factor."[18]

In spite of global oversupply, on 27 November 2014 in Vienna, Saudi Oil Minister Ali al-Naimi, blocked the appeals from the poorer OPEC member states, such as Venezuela, Iran and Algeria, for production cuts. Benchmark crude, Brent oil plunged to US$71.25, a four-year low. Al-Naimi argued that the market would be left to correct itself. OPEC had a "long-standing policy of defending prices." According to some analysts, OPEC will let price of Brent oil drop to US$60 to slow down US shale oil production.[19] In spite of a troubled economy in member countries, al-Naimi repeated his statement on Saudi inaction.[20]

By November 2014 with production at 30.56 million barrels per day (4,859,000 m3/d) OPEC entered its sixth month of exceeding their collective target production.[12]

By 11 December 2014 the price of OPEC Reference Basket of Crudes had dropped to US$60.50[11] and by 13 December the price of Brent ICE dropped to US$61.85.[12]

The 12 January 2015 price of OPEC Reference Basket of Crudes had dropped to US$43.55[11]

By February 2015, OPEC had entered its ninth consecutive month of exceeding their collective target production.[21]

Leadership

| Name | Country | Service Period |

|---|---|---|

| Dr Fuad Rouhani | Iran | 21 January 1961–30 April 1964 |

| Dr Abdul Rahman Al-Bazzaz | Iraq | 1 May 1964–30 April 1965 |

| Ashraf T. Lutfi | Kuwait | 1 May 1965–31 December 1966 |

| Mohammad Saleh Joukhdar | Saudi Arabia | 1 January 1967–31 December 1967 |

| Dr Francisco R. Parra | Venezuela | 1 January 1968–31 December 1968 |

| Dr Elrich Sanger | Indonesia | 1 January 1969–31 December 1969 |

| Omar El-Badri | Libyan Arab Republic | 1 January 1970–31 December 1970 |

| Dr Nadim Pachachi | UAE | 1 January 1971–31 December 1972 |

| Dr Abderrahman Khène | Algeria | 1 January 1973–31 December 1974 |

| Chief M.O. Feyide | Nigeria | 1 January 1975–31 December 1976 |

| Ali M. Jaidah | Qatar | 1 January 1977–31 December 1978 |

| René G. Ortiz | Ecuador | 1 January 1979–30 June 1981 |

| Dr Marc S. Nan Nguema | Gabon | 1 July 1981–30 June 1983 |

| Mana Saeed Otaiba*** | UAE | 19 July 1983–31 December 1983 |

| Kamal Hassan Maghur | SP Libyan AJ | 1 January 1984–31 October 1984 |

| Dr Subroto | Indonesia | 31 October 1984–9 December 1985 |

| Dr Arturo Hernández Grisanti | Venezuela | 1 January 1986–30 June 1986 |

| Dr Alhaji Rilwanu Lukman | Nigeria | 1 July 1986–30 June 1988 |

| Dr Subroto | Indonesia | 1 July 1988–30 June 1994 |

| Abdalla Salem El-Badri | SP Libyan AJ | 1 July 1994–31 December 1994 |

| Dr Alhaji Rilwanu Lukman | Nigeria | 1 January 1995–31 December 2000 |

| Dr Alí Rodríguez Araque | Venezuela | 1 January 2001–30 June 2002 |

| Dr Alvaro Silva Calderón | Venezuela | 1 July 2002–31 December 2003 |

| Dr Purnomo Yusgiantoro | Indonesia | 1 January 2004–31 December 2004 |

| Sheikh Ahmad Fahad Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah | Kuwait | 1 January 2005–31 December 2005 |

| Dr Edmund Maduabebe Daukoru | Nigeria | 1 January 2006–31 December 2006 |

| Abdalla Salem El-Badri | SP Libyan AJ | 1 January 2007–26 November 2014[22] |

| Dr Diezani Alison-Madueke | Nigeria | 27 November 2014–present}[23] |

Since 2007, Abdallah Salem el-Badri has been the Secretary General of OPEC. He is a citizen of Libya and resides in Austria.

Publications and research

Since 2007, OPEC publishes the World Oil Outlook (WOO) annually, in which it presents a comprehensive analysis of the global oil industry including OPEC projections for the medium-term and long-term for oil demand and supply.[24] In its 2014 WOO, OPEC projected that the price of oil would be US$110/b for the rest of the decade, although they were proved wrong by the plummet of crude oil prices in 2015.

OPEC spare capacity

The U.S. Energy Information Administration, the statistical arm of the U.S. Department of Energy, defines spare capacity for crude oil market management, "as the volume of production that can be brought on within 30 days and sustained for at least 90 days."[7] OPEC spare capacity "provides an indicator of the world oil market's ability to respond to potential crises that reduce oil supplies."[7]

In November 2014 the International Energy Agency estimated that OPEC's effective spare capacity was 3.52 million barrels per day (560,000 m3/d) and that this number would increase to a peak in 2017 of 4.60 million barrels per day (731,000 m3/d). In 2013 it was 3.06 million barrels per day (487,000 m3/d).[25]: 13 Saudi Arabia is the largest oil exporter in the world and largest oil producer of the OPEC nations. It has the greatest spare capacity at about 1.5 million barrels per day (240,000 m3/d) to 2 million barrels per day (320,000 m3/d).[7]

History

In 1949 Venezuela and Iran were the first countries to move towards the establishment of OPEC by approaching Iraq, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, suggesting that they exchange views and explore avenues for regular and closer communication among petroleum-producing nations.[26]

In 1959, the International Oil Companies (IOCs) reduced the posted price for Venezuelan crude by 5¢ and then 25¢ per barrel, and that for Middle Eastern crude by 18¢ per barrel.[26]

The First Arab Petroleum Congress convened in Cairo, Egypt, where they established an ‘Oil Consultation Commission’ to which IOCs should present price change plans to authorities of producing countries.[26] In 1959 journalist Wanda Jablonski introduced Abdullah Tariki to Juan Pablo Perez Alfonzo at the Arab Oil Congress in Cairo. They were both infuriated by the cut in posted prices by IOCs or Multinational Oil Companies (MOCs). This meeting resulted in the Maadi Pact or Gentlemen's Agreement.[8]: 499

In 1960, journalist Wanda Jablonski reported a marked hostility toward the West and a growing outcry against absentee landlordism in the Middle East. In his influential book entitled The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power, Daniel Yergin described how the Standard Oil, who controlled 75% of the US oil business, in August 1960 with no direct warning to oil exporters, announced cut of up 7 per cent of the posted prices of Middle Eastern crude oils. Esso and other oil companies unilaterally reduced the posted price for Middle East crudes.[27] Middle Eastern countries already felt resentment towards the West over the absentee landlordism of [8] MOCs who at the time controlled all oil operations within the host countries.[8]: 503

Founding

In 10–14 September 1960, the Baghdad conference was held at the initiative of the Venezuelan Mines and Hydrocarbons minister Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso and the Saudi Arabian Energy and Mines minister Abdullah al-Tariki. The governments of Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela met in Baghdad to discuss ways to increase the price of the crude oil produced by their respective countries and respond to unilateral actions by the MOCs who at the time controlled all oil operations within the host countries. "Together with Arab and non-Arab producers, Saudi Arabia formed the Organization of Petroleum Export Countries (OPEC) to secure the best price available from the major oil corporations."[28]

Iraq, Kuwait, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela were the OPEC founding member nations in 1960. Later it was joined by nine more governments: Libya(1962), United Arab Emirates(1967), Qatar(1961), Indonesia(1962- suspended its membership from January 2009), Algeria(1969), Nigeria(1971), Ecuador(1973 - suspended its membership from December 1992-October 2007), Angola(2007), and Gabon(1975–1994). The Arab countries originally called for OPEC headquarters to be in Bagdad or Beirut, but Venezuela argued for a neutral location, and so Geneva, Switzerland was chosen. However, on 1 September 1965, OPEC moved to Vienna, Austria.[29][30]

OPEC was founded to unify and coordinate members' petroleum policies. Between 1960 and 1975, the organization expanded to include Qatar , Indonesia, Libya, the United Arab Emirates, Algeria, and Nigeria. Ecuador and Gabon were early members of OPEC, but Ecuador withdrew on 31 December 1992[31] because it was unwilling or unable to pay a $2 million membership fee and felt that it needed to produce more oil than it was allowed to under the OPEC quota,[32] although it rejoined in October 2007. Similar concerns prompted Gabon to suspend membership in January 1995.[33] Angola joined on the first day of 2007. Norway and Russia have attended OPEC meetings as observers. Indicating that OPEC is not averse to further expansion, Mohammed Barkindo, OPEC's Secretary General, asked Sudan to join.[34] Iraq remains a member of OPEC, but Iraqi production has not been a part of any OPEC quota agreements since March 1998.

In the 1970s, OPEC began to gain influence and steeply raised oil prices during the 1973 oil crisis in response to US aid to Israel during the Yom Kippur War.[35] It lasted until March 1974.[36] OPEC added to its goals the selling of oil for socio-economic growth of the poorer member nations, and membership grew to 13 by 1975.[29] A few member countries became centrally planned economies.[29]

In a 1979 U.S. District Court decision held that OPEC’s pricing decisions have sovereign immunity as "governmental" acts of state, as opposed to "commercial" acts, and are therefore beyond the legal reach of U.S. courts competition law and are protected by the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976.[37][38]

In the 1980s, the price of oil was allowed to rise before the adverse effects of higher prices caused demand and price to fall. The OPEC nations, which depended on revenue from oil sales, experienced severe economic hardship from the lower demand for oil and consequently cut production in order to boost the price of oil. During this time, environmental issues began to emerge on the international energy agenda.[29] Lower demand for oil saw the price of oil fall back to 1986 levels by 1998–99.

In the 2000s, a combination of factors pushed up oil prices even as supply remained high. Prices rose to then record-high levels in mid-2008 before falling in response to the 2007 financial crisis. OPEC's summits in Caracas and Riyadh in 2000 and 2007 had guiding themes of stable energy markets, sustainable oil production, and environmental sustainability.[29]

In April 2001, OPEC, in collaboration with five other international organisations (APEC, Eurostat, IAE, OLADE and the UNSD) launched the Joint Oil Data Exercise, which became rapidely the Joint Organization Data Initiative (JODI).

In 2003 the International Energy Agency (IEA) and OPEC held their first joint workshop on energy issues and they continued to meet since then to better "understand trends, analysis and viewpoints and advance market transparency and predictability."[39]: 7

By 2011 OPEC called for more efforts by governments and regulatory bodies to curb excessive speculation in oil futures markets. OPEC claimed this increased volatility in oil prices, disconnected price from market fundamentals. In 2011 Nymex oil future trades reached record highs. By mid-March the Nymex WTI "exceeded 1.5 million futures contracts, 18 times higher than the volume of daily traded physical crude."[40]

While there have been some allegations that OPEC acted as a cartel when it adopted output rationing in order to maintain price in 1996, for example,[41] Jeff Colgan argued in 2013 that, since 1982, countries cheated on their quotas 96% of the time, largely neutralizing the ability of OPEC to collectively influence prices.[42]

In 2011 the U.S. Energy Information Administration estimated that OPEC would break above the US$1 trillion mark earnings for the first time at US$1.034 trillion. In 2008 OPEC earned US$965 billion.[43]

1973 oil embargo

In October 1973, OPEC declared an oil embargo in response to the United States' and Western Europe's support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War of 1973. The result was a rise in oil prices from $3 per barrel to $12 starting on 17 October 1973, and ending on 18 March 1974 and the commencement of gas rationing. Other factors in the rise in gasoline prices included a market and consumer panic reaction, the peak of oil production in the United States around 1970 and the devaluation of the U.S. dollar.[44] U.S. gas stations put a limit on the amount of gasoline that could be dispensed, closed on Sundays, and limited the days gasoline could be purchased based on license plates. Even after the embargo concluded, prices continued to rise.[45]

The Oil Embargo of 1973 had a lasting effect on the United States. The Federal government got involved first with President Richard Nixon recommending citizens reduce their speed for the sake of conservation, and later Congress issuing a 55 mph limit at the end of 1973. Daylight saving time was extended year round to reduce electrical use in the American home. Smaller, more fuel efficient cars were manufactured.

On 4 December 1973, Nixon also formed the Federal Energy Office as a cabinet office with control over fuel allocation, rationing, and prices.[46] People were asked to decrease their thermostats to 65 degrees and factories changed their main energy supply to coal.

One of the most lasting effects of the 1973 oil embargo was a global economic recession. Unemployment rose to the highest percentage on record while inflation also spiked. Consumer interest in large gas guzzling vehicles fell and production dropped. Although the embargo only lasted a year, during that time oil prices had quadrupled and OPEC nations discovered that their oil could be used as both a political and economic weapon against other nations.[47][48]

1975 hostage incident

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2011) |

On 21 December 1975, Ahmed Zaki Yamani and the other oil ministers of the members of OPEC were taken hostage in Vienna, Austria, where the ministers were attending a meeting at the OPEC headquarters. The hostage attack was orchestrated by a six-person team led by Venezuelan terrorist Carlos the Jackal (which included Gabriele Kröcher-Tiedemann and Hans-Joachim Klein). The self-named "Arm of the Arab Revolution" group called for the liberation of Palestine. Carlos planned to take over the conference by force and kidnap all eleven oil ministers in attendance and hold them for ransom, with the exception of Ahmed Zaki Yamani and Iran's Jamshid Amuzegar, who were to be executed.

The terrorists searched for Ahmed Zaki Yamani and then divided the sixty-three hostages into groups. Delegates of friendly countries were moved toward the door, 'neutrals' were placed in the centre of the room and the 'enemies' were placed along the back wall, next to a stack of explosives. This last group included those from Saudi Arabia, Iran, Qatar and the UAE.

Carlos arranged bus and plane travel for the team and 42 hostages, with stops in Algiers and Tripoli, with the plan to eventually fly to Aden then Baghdad, where Yamani and Amuzegar would be killed. All 30 non-Arab hostages were released in Algiers, excluding Amuzegar. Additional hostages were released at another stop. With only 10 hostages remaining, Carlos held a phone conversation with Algerian President Houari Boumédienne who informed Carlos that the oil ministers' deaths would result in an attack on the plane. Boumédienne must also have offered Carlos asylum at this time and possibly financial compensation for failing to complete his assignment. Carlos expressed his regret at not being able to murder Yamani and Amuzegar, then he and his comrades left the plane. Hostages and Carlos and his team walked away from the situation.

Some time after the attack it was revealed by Carlos' accomplices that the operation was commanded by Wadi Haddad, a Palestinian terrorist and founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. It was also claimed that the idea and funding came from an Arab president, widely thought to be Muammar al-Gaddafi. In the years following the OPEC raid, Bassam Abu Sharif and Klein claimed that Carlos had received a large sum of money in exchange for the safe release of the Arab hostages and had kept it for his personal use. There is still some uncertainty regarding the amount that changed hands but it is believed to be between US$20 million and US$50 million. The source of the money is also uncertain, but, according to Klein, it was from "an Arab president." Carlos later told his lawyers that the money was paid by the Saudis on behalf of the Iranians and was, "diverted en route and lost by the Revolution".[49]

The 1980s oil gluts

In response to the high oil prices of the 1970s, industrial nations took steps to reduce dependence on oil. Utilities switched to using coal, natural gas, or nuclear power while national governments initiated multi-billion dollar research programs to develop alternatives to oil. Demand for oil dropped by five million barrels a day while oil production outside of OPEC rose by fourteen million barrels daily by 1986. During this time, the percentage of oil produced by OPEC fell from 50% to 29%. The result was a six-year price decline that culminated with a 46 percent price drop in 1986.

In order to combat falling revenues, Saudi Arabia pushed for production quotas to limit production and boost prices. When other OPEC nations failed to comply, Saudi Arabia slashed production from 10 million barrels daily in 1980 to just one-quarter of that level in 1985. When this proved ineffective, Saudi Arabia reversed course and flooded the market with cheap oil, causing prices to fall to under ten dollars a barrel. The result was that high price production zones in areas such as the North Sea became too expensive. Countries in OPEC that had previously failed to comply to quotas began to limit production in order to shore up prices.[51]

Responding to war and low prices

Leading up to the 1990–91 Gulf War, The President of Iraq Saddam Hussein recommended that OPEC should push world oil prices up, helping all OPEC members financially. But the division of OPEC countries occasioned by the Iraq-Iran War and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait marked a low point in the cohesion of OPEC. Once supply disruption fears that accompanied these conflicts dissipated, oil prices began to slide dramatically.

After oil prices slumped at around $15 a barrel in the late 1990s, joint diplomacy achieved a slowing down of oil production beginning in 1998.

In 2000, Venezuela President Hugo Chávez hosted the first summit of OPEC in 25 years in Caracas. The next year, however, the September 11, 2001 attacks against the United States, and the following invasion of Afghanistan, and 2003 invasion of Iraq and subsequent occupation prompted a sharp rise in oil prices to levels far higher than those targeted by OPEC themselves during the previous period.

In May 2008, Indonesia announced that it would leave OPEC when its membership expired at the end of that year, having become a net importer of oil and being unable to meet its production quota.[52] A statement released by OPEC on 10 September 2008 confirmed Indonesia's withdrawal, noting that it "regretfully accepted the wish of Indonesia to suspend its full Membership in the Organization and recorded its hope that the Country would be in a position to rejoin the Organization in the not too distant future."[53] Indonesia is still exporting light, sweet crude oil and importing heavier, more sour crude oil to take advantage of price differentials (import is greater than export).

Production disputes

The economic needs of the OPEC member states often affects the internal politics behind OPEC production quotas. Various members have pushed for reductions in production quotas to increase the price of oil and thus their own revenues.[54] These demands conflict with Saudi Arabia's stated long-term strategy of being a partner with the world's economic powers to ensure a steady flow of oil that would support economic expansion.[55] Part of the basis for this policy is the Saudi concern that expensive oil or supply uncertainty will drive developed nations to conserve and develop alternative fuels. To this point, former Saudi Oil Minister Sheikh Yamani famously said in 1973: "The stone age didn't end because we ran out of stones."[56]

On 10 September 2008, one such production dispute occurred when the Saudis reportedly walked out of OPEC negotiating session where the organization voted to reduce production. Although Saudi Arabian OPEC delegates officially endorsed the new quotas, they stated anonymously that they would not observe them. The New York Times quoted one such anonymous OPEC delegate as saying "Saudi Arabia will meet the market’s demand. We will see what the market requires and we will not leave a customer without oil. The policy has not changed."[57]

OPEC aid

OPEC aid dates from well before the 1973/74 oil price explosion. Kuwait has operated a program since 1961 (through the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development).

The OPEC Special Fund "was conceived [...] in Algiers, Algeria, in March 1975", and formally founded early the following year. "A Solemn Declaration 'reaffirmed the natural solidarity which unites OPEC countries with other developing countries in their struggle to overcome underdevelopment,' and called for measures to strengthen cooperation between these countries", operating under a reasoning that the Fund's "resources are additional to those already made available by OPEC states through a number of bilateral and multilateral channels." The Fund was later renamed as the OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID).[58][59]

The Fund became a fully fledged permanent international development agency in May 1980 and was renamed the OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID), the designation it currently holds.

Membership

Current members

OPEC has twelve member countries: six in the Middle East (Western Asia), four in Africa, and two in South America.

| Country | Region | Joined OPEC[60] | Population (July 2012)[61] |

Area (km²)[62] | Production (bbl/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 1969 | 37,367,226 | 2,381,740 | 2,125,000 (16th) | |

| Africa | 2007 | 18,056,072 | 1,246,700 | 1,948,000 (17th) | |

| South America | (1973) 2007[A 1] | 15,223,680 | 283,560 | 485,700 (30th) | |

| Middle East (Western Asia) | 1960[A 2] | 78,868,711 | 1,648,000 | 6,172,000 (4th) | |

| Middle East (Western Asia) | 1960[A 2] | 31,129,225 | 437,072 | 3,200,000 (7th) | |

| Middle East (Western Asia) | 1960[A 2] | 2,646,314 | 17,820 | 4,500,000 (5th) | |

| Africa | 1962 | 5,613,380 | 1,759,540 | 2,210,000 (15th) | |

| Africa | 1971 | 170,123,740 | 923,768 | 2,211,000 (14th) | |

| Middle East (Western Asia) | 1961 | 1,951,591 | 11,437 | 1,213,000 (21st) | |

| Middle East (Western Asia) | 1960[A 2] | 26,534,504 | 2,149,690 | 12,500,000 (2nd) | |

| Middle East (Western Asia) | 1967 | 5,314,317 | 83,600 | 2,798,000 (8th) | |

| South America | 1960[A 2] | 28,047,938 | 912,050 | 2,472,000 (11th) | |

| Total | 369,368,429 | 11,854,977 km² | 33,327,700 bbl/day | ||

Former members

| Country | Region | Joined OPEC | Left OPEC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 1975 | 1994 | |

| Southeast Asia | 1962 | 2009 |

Some commentators consider that the United States was a de facto member during its formal occupation of Iraq due to its leadership of the Coalition Provisional Authority.[63][64] But this is not borne out by the minutes of OPEC meetings, as no US representative attended in an official capacity.[65][66]

Indonesia left OPEC in 2009 because it ceased to be a net exporter of oil. It could not fulfill the demand of its own country's needs, as growth in demand outstripped output. The situation was made worse because of weak legal certainty and corruption that deterred foreign investors from investing in new reserves in Indonesia. In recent times, the government has increased financial incentives for foreign firms to invest in exploration and extraction but has found itself forced to import more supplies from the likes of Iran, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Indonesia's departure from OPEC will not likely affect the amount of oil it produces or imports.[67]

Saudi Arabia

Oil reserves in Saudi Arabia are the second largest claimed in the world, estimated to be 267 billion barrels (42×109 m3) (Gbbl hereafter), including 2.5 Gbbl in the Saudi–Kuwaiti neutral zone. These reserves were the largest in the world until Venezuela announced they had increased their proven reserves to 297 Gbbl in January 2011.[68] The Saudi reserves are about one-fifth of the world's total conventional oil reserves, a large fraction of these reserves comes from a small number of very large oil fields, and past production amounts to 40% of the stated reserves.

Saudi Aramco, (formerly Arabian-American Oil Company) is the Saudi Arabian national oil company.[69][70] Valued at about US$10 trillion in 2010 [71][72][73] with total assets at about US$30 trillion, it was the world's largest company.[74] It has both the world's largest proven crude oil reserves, at more than 260 billion barrels (4.1×1010 m3),[75] and largest daily oil production.[76]

Venezuela

In November 2013 Venezuela produced 2.69 million barrels per day (428,000 m3/d); in 2014 the production fell to 2.47 million barrels per day (393,000 m3/d)[12] In 2014 96 per cent of Venezuela's dollar earnings came from its oil exports.[12]

Nigeria

Nigeria is the largest exporter of crude oil in Africa and has the largest economy in Africa.[77] Nigeria's petroleum is classified mostly as "light" and "sweet", as the oil is largely free of sulphur. Nigeria is the largest producer of sweet oil in OPEC. This sweet oil is similar in composition to petroleum extracted from the North Sea. This crude oil is known as "Bonny light". Names of other Nigerian crudes, all of which are named according to export terminal, are Qua Ibo, Escravos blend, Brass river, Forcados, and Pennington Anfan.

Sustainability

In 2009, Mikael Höök, argued that despite technological advances that increase the productivity of oil wells, the rate of decline of oil fields would eventually increase as time continues.[78]

In 2010, energy policy expert Joyce Dargay accused OPEC, along with several other institutions, of drastically underpredicting future oil demand by 2030 by more than 25%, a difference of 28 million barrels per day (4,500,000 m3/d) or about twice the current amount supplied by Saudi Arabia.[79]

See also

- Seven Sisters (oil companies)

- Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC)

- Organization of Petroleum Importing Countries

- Petroleum politics

- Gas Exporting Countries Forum

Citations

- ^ "OPEC Statute" (PDF). Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. 2008. p. 8. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

English shall be the official language of the Organization.

- ^ a b "2014 World Oil Outlook (WOO)" (PDF), OPEC, Vienna, p. 396, 2014, ISBN 978-3-9502722-8-4

- ^ "About", OPEC, Vienna, nd, retrieved 12 December 2014

- ^ "Statute" (PDF), OPEC, 2012, retrieved 12 December 2014

- ^ "Opec and Oil Prices: Leaky Barrels". The Economist. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Our Mission". OPEC. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Energy & Financial Markets: What Drives Crude Oil Prices?", EIA, 2014, retrieved 12 December 2014

- ^ a b c d e f Yergin, Daniel (1991), The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power, New York: Simon & Schuster

- ^ http://www.lloydslist.com/ll/news/top100/article453573.ece

- ^ http://www.eppo.go.th/inter/opec/OPEC-about.html

- ^ a b c "OPEC daily basket price stood at $60.50 a barrel", OPEC, Vienna, 11 December 2014, retrieved 12 December 2014

- ^ a b c d e f "Venezuela hasn't Officially Requested Emergency OPEC Meeting", Bloomberg, 12 December 2014, retrieved 13 December 2014

- ^ a b c Krassnov, Clifford (3 November 2014), "U.S. Oil Prices Fall Below $80 a Barrel", New York Times, retrieved 13 December 2014

- ^ a b "Increases in U.S. crude oil production come from light, sweet crude from tight formations", EIA, 6 June 2014, retrieved 13 December 2014

- ^ a b c d U.S. Crude Oil Production Forecast Analysis of Crude Types (PDF), 29 May 2014, retrieved 13 December 2014

- ^ Nelson, Kristen (13 December 2014), EIA: Brent crude spot price peaks in June, Petroleum News

- ^ "Saudi Aramco continues to slash crude prices to Asia", Platts, New York, 1 October 2014, retrieved 12 December 2014

- ^ Abdourhman Ataher Al-Ahirish (27 November 2014), Opening address to the 166th Meeting of the OPEC Conference, Press Release, Vienna, Austria, retrieved 12 December 2014

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|conference=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lawler, Alex; Sheppard, David; El Gamal, Rania (27 November 2014), Saudis block OPEC output cut, sending oil price plunging, Vienna: Reuters, retrieved 10 December 2014

- ^ Krishnan, Barani (10 December 2014), Oil crashes 5%, nears $60 on weak U.S. demand, Saudi inaction, London: Globe and Mail via Reuters, retrieved 10 December 2014

- ^ "Crude Oil Rallies as Dollar Crumbles", FXTimes, 20 March 2014, retrieved 23 March 2015

- ^ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diezani_Alison-Madueke

- ^ "Secretaries General of OPEC 1961-2008" (PDF). Opec.org. Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ "Executive Summary of World Oil Outlook" (PDF), OPEC, Vienna, Austria, 2014

- ^ Munro, Diane (November 2014), "Effective OPEC Spare Capacity Reality-Data" (PDF), Energy: the Journal of the International Energy Agency (7), Paris: International Energy Agency, retrieved 12 December 2014

- ^ a b c "General Information - OPEC" (PDF). OPEC.org. 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- ^ Painter 2012, p. 32.

- ^ Citino, 2002 & 4.

- ^ a b c d e "Brief History". OPEC. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ "OPEC : Brief History". Opec.org. Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ Archived 2002-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ecuador Set to Leave OPEC". The New York Times. 18 September 1992. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Gabon Plans To Quit OPEC". The New York Times. 9 January 1995. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ Angola, Sudan to ask for OPEC membership Houston Chronicle

- ^ "Responding to Crisis". Envhist. 26 April 2010. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ "OPEC Oil Embargo 1973–1974". U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ Weil, Dan (25 November 2007). "If OPEC is a Cartel, Why isn't It Illegal?". Newsmax. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite jstor}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by jstor:40704964, please use {{cite journal}} with

|jstor=40704964instead. - ^ "Dialogue replaces OPEC-IEA Mistrust" (PDF), Energy: the Journal of the International Energy Agency (7), Paris: International Energy Agency, November 2014, retrieved 12 December 2014

- ^ "Opening address to the 159th Meeting of the OPEC Conference", OPEC, 2011, retrieved 12 December 2014

- ^ Gülen, S. Gürcan (1996). "Is OPEC a Cartel? Evidence from Cointegration and Causality Tests" (PDF). The Energy Journal. 17 (2): 43–57. doi:10.5547/issn0195-6574-ej-vol17-no2-3.

- ^ Colgan, Jeff (16 October 2013). "40 years after the oil crisis: Could it happen again?". Washington Post. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Blais, Javier (15 June 2011), OPEC eyes record revenues above $1-trillion, Financial Times, retrieved 12 December 2014

- ^ Leonardo Maugeri (1 January 2006). The Age of Oil: The Mythology, History, and Future of the World's Most Controversial Resource. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-275-99008-4.

- ^ Clark,F.,Hushour,J.,Reinholtz,N.,Reniers,A.,Rich,S.,Smith,A.Z.,Torres,J.,(2009, 2010). The plaid avenger. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

- ^ Buck, Alice. "A History of the Energy Research and Development Administration" (PDF). energy.gov. US Department of Energy. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ "1973 Oil crisis" (PDF). Environment. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ OPEC inflicted two devastating oil shocks Socialism Today (51) October 2000

- ^ "Carlos the Jackal: Trail of Terror, Parts 1 and 2 — 'The Famous Carlos'". Trutv. Retrieved 23 October 2010.

- ^ "OPEC Revenues". U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Robert 2004, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Indonesia to withdraw from OPEC BBC. 28 May 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ Archived 2008-09-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Nick A. Owen, Oliver R. Inderwildi, David A. King (2010). "The status of conventional world oil reserves – Hype or cause for concern?". Energy Policy. 38 (8): 4743–4749. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.02.026.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Speech by Minister of Petroleum and Mineral Resources Ali Al Naimi: Saudi oil policy: stability with strength Saudi Embassy. 1999.

- ^ Matt Frei. (3 July 2008). Washington diary: Oil addiction BBC. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ Saudis Vow to Ignore OPEC Decision to Cut Production The New York Times. 11 September 2008.

- ^ OFID at a Glance OFID. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ "50th Anniversary", OPEC, 2010, retrieved 12 December 2014

- ^ "OPEC: Member countries". Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ^ "Field Listing – Population". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ "Field Listing – Area". CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ Timothy Noah (10 July 2007). "Go NOPEC". Slate. Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ Timothy Noah (18 September 2003). "Is Bremer a Price Fixer? Letting Iraq's oil minister attend an OPEC meeting may violate the Sherman Antitrust Act". Slate.

- ^ "Iraq to Attend Next OPEC Ministerial Meeting". Arab News. 17 September 2003. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ "127th Meeting of the OPEC Conference". OPEC. 24 September 2003. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ "Indonesia to withdraw from OPEC". BBC News. 28 May 2008.

- ^ Venezuela: Oil reserves surpasses Saudi Arabia's at english.ahram.org.eg

- ^ The Report: Saudi Arabia 2009. Oxford Business Group. 2009. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-907065-08-8.

- ^ "Our company. At a glance". Saudi Aramco.

The Saudi Arabian Oil Co. (Saudi Aramco) is the state-owned oil company of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

- ^ "Big Oil, bigger oil". Financial Times. 4 February 2010.

- ^ Sheridan Titman, "Texas Enterprise - What's the Value of Saudi Aramco?". 9 February 2010.

- ^ Helman, Christopher (9 July 2010). "The World's Biggest Oil Companies". Forbes.

- ^ Saudi Aramco Report, ireport.ccn.com; accessed 11 November 2014.

- ^ Saudi Aramco Facts & Figures 2013

- ^ News SteelGuru.com; accessed 11 November 2014.

- ^ Chizea, Boniface (3 November 2014), "The Falling Oil Price And Implications For Nigeria", The Leadership, retrieved 13 December 2014

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2009.02.020, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.enpol.2009.02.020instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.06.014, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.enpol.2010.06.014instead.

References

- Citino, Nathan J. (2002). From Arab Nationalism to OPEC: Eisenhower, King Sa'ud, and the Making of U.S.-Saudi Relations. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34095-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Evans, John (1993), Brown, Gavin (ed.), OPEC and the World Energy Market: A Comprehensive Reference Guide (2nd ed.), Burnt Mill, Harlow, Essex, U.K.: Longman, p. 749

- Painter, David S. (2012). "Oil and the American Century" (PDF). The Journal of American History. 99 (1): 24–39. doi:10.1093/jahist/jas073.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Robert, Paul (2004). The End of Oil: The Decline of the Petroleum Economy and the Rise of a New Energy Order. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-618-23977-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Sampson, Anthony (1991), The Seven Sisters: The Great Oil Companies and the World They Shaped, New York: Bantam Books, p. 414

- Skeet, Ian (1988), Twenty-Five Years of Prices and Politics, Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 263

External links

- Official website

- Zycher, Benjamin (2008). "OPEC". In David R. Henderson (ed.) (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - OPEC Timeline by Nicolas Sarkis, from Le Monde diplomatique, May 2006

- The OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID) official site

- Stefan Schaller on OPEC's inability to control the market

- Statistics of the fuel oil prices from 2010 to 2011 in Germany, PDF – May 2011

- U.S Energy Information Administration - OPEC Revenues Fact Sheet, 24 July 2014

- OPEC World Oil Outlook, 6 November 2014