Nuclear ethics

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

Nuclear ethics is a cross-disciplinary field of academic and policy-relevant study in which the problems associated with nuclear warfare, nuclear deterrence, nuclear arms control, nuclear disarmament, or nuclear energy are examined through one or more ethical or moral theories or frameworks.[1][2][3] In contemporary security studies, the problems of nuclear warfare, deterrence, proliferation, and so forth are often understood strictly in political, strategic, or military terms.[4] In the study of international organizations and law, however, these problems are also understood in legal terms.[5] Nuclear ethics assumes that the very real possibilities of human extinction, mass human destruction, or mass environmental damage which could result from nuclear warfare are deep ethical or moral problems. Specifically, it assumes that the outcomes of human extinction, mass human destruction, or environmental damage count as moral evils. Another area of inquiry concerns future generations and the burden that nuclear waste and pollution imposes on them. Some scholars have concluded that it is therefore morally wrong to act in ways that produce these outcomes, which means it is morally wrong to engage in nuclear warfare.[6]

Nuclear ethics is interested in examining policies of nuclear deterrence, nuclear arms control and disarmament, and nuclear energy insofar as they are linked to the cause or prevention of nuclear warfare. Ethical justifications of nuclear deterrence, for example, emphasize its role in preventing great power nuclear war since the end of World War II.[7] Indeed, some scholars claim that nuclear deterrence seems to be the morally rational response to a nuclear-armed world.[8] Moral condemnation of nuclear deterrence, in contrast, emphasizes the seemingly inevitable violations of human and democratic rights which arise.[9]

Early ethical issues

The application of nuclear technology, both as a source of energy and as an instrument of war, has been controversial.[10][11][12][13]

Even before the first nuclear weapons had been developed, scientists involved with the Manhattan Project were divided over the use of the weapon. The role of the two atomic bombings of the country in Japan's surrender and the U.S.'s ethical justification for them has been the subject of scholarly and popular debate for decades. The question of whether nations should have nuclear weapons, or test them, has been continually and nearly universally controversial.[14]

The public became concerned about nuclear weapons testing from about 1954, following extensive nuclear testing in the Pacific. In 1961, at the height of the Cold War, about 50,000 women brought together by Women Strike for Peace marched in 60 cities in the United States to demonstrate against nuclear weapons.[15][16] In 1963, many countries ratified the Partial Test Ban Treaty which prohibited atmospheric nuclear testing.[17]

Some local opposition to nuclear power emerged in the early 1960s,[18] and in the late 1960s some members of the scientific community began to express their concerns.[19] In the early 1970s, there were large protests about a proposed nuclear power plant in Wyhl, Germany. The project was cancelled in 1975 and anti-nuclear success at Wyhl inspired opposition to nuclear power in other parts of Europe and North America. Nuclear power became an issue of major public protest in the 1970s.[20]

Uranium mining and milling

Between 1949 and 1989, over 4,000 uranium mines in the Four Corner region of the American Southwest produced more than 225,000,000 tons of uranium ore. This activity affected a large number of Native American nations, including the Laguna, Navajo, Zuni, Southern Ute, Ute Mountain, Hopi, Acoma and other Pueblo cultures.[21][22] Many of these peoples worked in the mines, mills and processing plants in New Mexico, Arizona, Utah and Colorado.[23] These workers were not only poorly paid, they were seldom informed of dangers nor were they given appropriate protective gear.[24] The government, mine owners, scientific, and health communities were all well aware of the hazards of working with radioactive materials at this time.[25][26] Due to the Cold War demand for increasingly destructive and powerful nuclear weapons, these laborers were both exposed to and brought home large amounts of radiation in the form of dust on their clothing and skin.[27] Epidemiologic studies of the families of these workers have shown increased incidents of radiation-induced cancers, miscarriages, cleft palates and other birth defects.[28] The extent of these genetic effects on indigenous populations and the extent of DNA damage remains to be resolved.[29][30][31][32] Uranium mining on the Navajo reservation continues to be a disputed issue as former Navajo mine workers and their families continue to suffer from health problems.[33]

Notable nuclear weapons accidents

- February 13, 1950: a Convair B-36B crashed in northern British Columbia after jettisoning a Mark IV atomic bomb. This was the first such nuclear weapon loss in history.

- May 22, 1957: a 42,000-pound Mark-17 hydrogen bomb accidentally fell from a bomber near Albuquerque, New Mexico. The detonation of the device's conventional explosives destroyed it on impact and formed a crater 25-feet in diameter on land owned by the University of New Mexico. According to a researcher at the Natural Resources Defense Council, it was one of the most powerful bombs made to date.[34]

- 7 June 1960: the 1960 Fort Dix IM-99 accident destroyed a Boeing CIM-10 Bomarc nuclear missile and shelter and contaminated the BOMARC Missile Accident Site in New Jersey.

- 24 January 1961: the 1961 Goldsboro B-52 crash occurred near Goldsboro, North Carolina. A B-52 Stratofortress carrying two Mark 39 nuclear bombs broke up in mid-air, dropping its nuclear payload in the process.[35][36]

- 1965 Philippine Sea A-4 crash, where a Skyhawk attack aircraft with a nuclear weapon fell into the sea.[37] The pilot, the aircraft, and the B43 nuclear bomb were never recovered.[38] It was not until the 1980s that the Pentagon revealed the loss of the one-megaton bomb.[39]

- January 17, 1966: the 1966 Palomares B-52 crash occurred when a B-52G bomber of the USAF collided with a KC-135 tanker during mid-air refuelling off the coast of Spain. The KC-135 was completely destroyed when its fuel load ignited, killing all four crew members. The B-52G broke apart, killing three of the seven crew members aboard.[40] Of the four Mk28 type hydrogen bombs the B-52G carried,[41] three were found on land near Almería, Spain. The non-nuclear explosives in two of the weapons detonated upon impact with the ground, resulting in the contamination of a 2-square-kilometer (490-acre) (0.78 square mile) area by radioactive plutonium. The fourth, which fell into the Mediterranean Sea, was recovered intact after a 2½-month-long search.[42]

- January 21, 1968: the 1968 Thule Air Base B-52 crash involved a United States Air Force (USAF) B-52 bomber. The aircraft was carrying four hydrogen bombs when a cabin fire forced the crew to abandon the aircraft. Six crew members ejected safely, but one who did not have an ejection seat was killed while trying to bail out. The bomber crashed onto sea ice in Greenland, causing the nuclear payload to rupture and disperse, which resulted in widespread radioactive contamination.

- September 18–19, 1980: the Damascus Accident, occurred in Damascus, Arkansas, where a Titan missile equipped with a nuclear warhead exploded. The accident was caused by a maintenance man who dropped a socket from a socket wrench down an 80-foot shaft, puncturing a fuel tank on the rocket. Leaking fuel resulted in a hypergolic fuel explosion, jettisoning the W-53 warhead beyond the launch site.[43][44][45]

Nuclear fallout

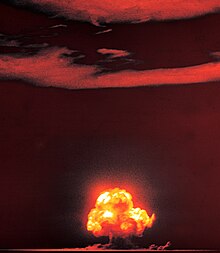

Over 500 atmospheric nuclear weapons tests were conducted at various sites around the world from 1945 to 1980. Radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing was first drawn to public attention in 1954 when the Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb test at the Pacific Proving Grounds contaminated the crew and catch of the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon.[17] One of the fishermen died in Japan seven months later, and the fear of contaminated tuna led to a temporary boycotting of the popular staple in Japan. The incident caused widespread concern around the world, especially regarding the effects of nuclear fallout and atmospheric nuclear testing, and "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of the anti-nuclear weapons movement in many countries".[17]

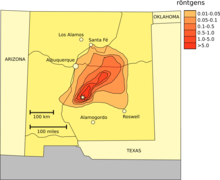

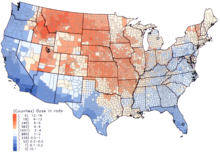

As public awareness and concern mounted over the possible health hazards associated with exposure to the nuclear fallout, various studies were done to assess the extent of the hazard. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/ National Cancer Institute study claims that fallout from atmospheric nuclear tests would lead to perhaps 11,000 excess deaths amongst people alive during atmospheric testing in the United States from all forms of cancer, including leukemia, from 1951 to well into the 21st century.[46][47] As of March 2009, the U.S. is the only nation that compensates nuclear test victims. Since the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990, more than $1.38 billion in compensation has been approved. The money is going to people who took part in the tests, notably at the Nevada Test Site, and to others exposed to the radiation.[48][49]

Nuclear labor issues

Nuclear labor issues exist within the nuclear power industry and the nuclear weapons production sector that impact upon the lives and health of laborers, itinerant workers and their families.[50][51][52] This subculture of frequently undocumented workers (e.g., Radium Girls, the Fukushima 50, Liquidators, and Nuclear Samurai) do the dirty, difficult, and potentially dangerous work shunned by regular employees.[53] When they exceed their allowable radiation exposure limit at a specific facility, they often migrate to a different nuclear facility. The industry implicitly accepts this conduct as it can not operate without these practices.[54][55]

Existent labor laws protecting worker’s health rights are not properly enforced.[56] Records are required to be kept, but frequently they are not. Some personnel were not properly trained resulting intheir own exposure to toxic amounts of radiation. At several facilities there are ongoing failures to perform required radiological screenings or to implement corrective actions.

Many questions regarding these nuclear worker conditions go unanswered, and with the exception of a few whistleblowers, the vast majority of laborers - unseen, underpaid, overworked and exploited, have few incentives to share their stories.[57] The median annual wage for hazardous radioactive materials removal workers, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics is $37,590 in the U.S - $18 per hour.[58] A 15-country collaborative cohort study of cancer risks due to exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation, involving 407,391 nuclear industry workers showed significant increase in cancer mortality. The study evaluated 31 types of cancers, primary and secondary.[59]

Civil liberties

Nuclear power may be a potential target for terrorists, and also increases the chances of nuclear weapons proliferation. Circumventing these problems involves cutting back on civil liberties, such as freedom of speech and assembly. So, Brian Martin says that "nuclear power is not a suitable power source for a free society".[60]

Human radiation experiments

The Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments (ACHRE) was formed on January 15, 1994 by President Bill Clinton. Hazel O"Leary, the Secretary of Energy at the U.S. Department of Energy called for a policy of "new openness", initiating the release of over 1.6 million pages of classified documents. These records revealed that since the 1940s, the Atomic Energy Commission was conducting widespread testing on human beings without their consent. Children, pregnant women, as well as male prisoners were injected with or orally consumed radioactive materials.[61]

References

- ^ Doyle, II, Thomas E. (2010). "Reviving Nuclear Ethics: A Renewed Research Agenda for the Twenty-first Century". Ethics and International Affairs. 24 (3): 287–308. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7093.2010.00268.x.

- ^ Nye, Jr., Joseph (1986). Nuclear Ethics. New York, NY: The Free Press. ISBN 0-02-923091-8.

- ^ Sohail H. Hashmi and Steven P. Lee, ed. (2004). Ethics and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Religious and Secular Perspectives. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-54526-9.

- ^ Buzan, Barry; Hansen, Lene (2009). "4". The Evolution of International Security Studies. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69422-3.

- ^ Szasz, Paul C. (2004). "2". In Sohail H. Hashmi and Steven P. Lee (ed.). Ethics and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Religious and Secular Perspectives. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–72.

- ^ Doyle, II, Thomas E. (2010). "Kantian nonideal theory and nuclear proliferation". International Theory. 2 (1): 87–112. doi:10.1017/s1752971909990248.

- ^ Nye, Jr., Joseph S (1986). "5". Nuclear Ethics. New York NY: The Free Press. pp. 59–80.

- ^ Kavka, Greg S. (1978). "Some Paradoxes of Deterrence". Journal of Philosophy. 75 (6): 285–302. doi:10.2307/2025707.

- ^ Shue, Henry (2004). "7". In Sohail H. Hashmi and Steven P. Lee (ed.). Ethics and Weapons of Mass Destruction: Religious and Secular Perspectives. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 139–162.

- ^ "Sunday Dialogue: Nuclear Energy, Pro and Con". New York Times. February 25, 2012.

- ^ Robert Benford. The Anti-nuclear Movement (book review) American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 89, No. 6, (May 1984), pp. 1456-1458.

- ^ James J. MacKenzie. Review of The Nuclear Power Controversy by Arthur W. Murphy The Quarterly Review of Biology, Vol. 52, No. 4 (Dec., 1977), pp. 467-468.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press.

- ^ Jerry Brown and Rinaldo Brutoco (1997). Profiles in Power: The Anti-nuclear Movement and the Dawn of the Solar Age, Twayne Publishers, pp. 191-192.

- ^ Woo, Elaine (January 30, 2011). "Dagmar Wilson dies at 94; organizer of women's disarmament protesters". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (January 23, 2011). "Dagmar Wilson, Anti-Nuclear Leader, Dies at 94". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 54-55.

- ^ Garb, Paula. "Review of Critical Masses". Journal of Political Ecology. 6: 1999.

- ^ Wolfgang Rudig (1990). Anti-nuclear Movements: A World Survey of Opposition to Nuclear Energy, Longman, p. 52.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, pp. 95-96.

- ^ Masco, Joseph (2006). The Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post-Cold War New Mexico. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12076-8.

- ^ Pasternak, Judy (2010). Yellow Dirt: An American Story of a Poisoned Land and a People Betrayed. New York, NY: Free Press, Simon & Schuster, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4165-9482-6.

- ^ Kuletz, Valerie L. (1998). The Tainted Desert: Environmental and Social Ruin in the American West. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-91770-0.

- ^ Johnston, editor, Barbara Rose (2007). Half-Lives and Half Truths: Confronting the Radioactive Legacies of the Cold War. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press. ISBN 978-1-930618-82-4.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ Brugge, Doug; Timothy Benally, Ester Yazzie Lewis. "Uranium Mining on Navajo Indian Land". Partnering with Indigenous Peoples to Defend their Lands, Languages and Cultures. Cultural Survival.org. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hevly, editors, Bruce; Findlay, John M. (1998). The Atomic West. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97749-3.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ Amundson, Michael A. (2002). Yellowcake Towns: Uranium Mining Communities in the American West. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-662-4.

- ^ Laramee, Eve Andree. "Tracking Our Nuclear Legacy: Now we are all sons of bitches". 2012. WEAD: Women Environmental Artist Directory. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Frosh, Dan (July 26, 2009). "Uranium Contamination Haunts Navajo Country". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Johnston, Barbara Rose; Holly M. Barker; Marie I. Boutte; Susan Dawson; Paula Garb; Hugh Gusterson; Joshua Levin; Edward Liebow; Gary E. Madsen; David H. Price; Kathleen Purvis-Roberts; Theresa Satterfield; Edith Turner; Cynthia Werner (2007). Half Lives & Half Truths: Confronting the Radioactive Legacies of the Cold War. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press. ISBN 1-930618-82-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brugge, Doug; Timothy Benally, Esther Yazzie-Lewis (2007). The Navajo People and Uranium Mining. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-3779-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jung, Carrie. "Navajo Nation Opposes Uranium Mine on Sacred Site in New Mexico". Al Jazerra. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Reese, April (May 12, 2011). "Navajo Group to Take Uranium Mine Challenge to Human Rights Commission". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ "Accident Revealed After 29 Years: H-Bomb Fell Near Albuquerque in 1957". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. August 27, 1986. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Barry Schneider (May 1975). "Big Bangs from Little Bombs". Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. p. 28. Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- ^ James C. Oskins, Michael H. Maggelet (2008). Broken Arrow — The Declassified History of U.S. Nuclear Weapons Accidents. lulu.com. ISBN 1-4357-0361-8. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- ^ "Ticonderoga Cruise Reports" (Navy.mil weblist of Aug 2003 compilation from cruise reports). Retrieved 2012-04-20.

The National Archives hold[s] deck logs for aircraft carriers for the Vietnam Conflict.

- ^ Broken Arrows at www.atomicarchive.com. Accessed Aug 24, 2007.

- ^ "U.S. Confirms '65 Loss of H-Bomb Near Japanese Islands". The Washington Post. Reuters. May 9, 1989. p. A–27.

- ^ Hayes, Ron (January 17, 2007). "H-bomb incident crippled pilot's career". Palm Beach Post. Archived from the original on 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

- ^ Maydew, Randall C. (1997). America's Lost H-Bomb: Palomares, Spain, 1966. Sunflower University Press. ISBN 978-0-89745-214-4.

- ^ Long, Tony (January 17, 2008). "Jan. 17, 1966: H-Bombs Rain Down on a Spanish Fishing Village". WIRED. Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- ^ Schlosser, Eric (2013). Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-227-8.

- ^ Christ, Mark K. "Titan II Missile Explosion". The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. Arkansas Historic Preservation Program. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Stumpf, David K. (2000). Christ, Mark K.; Slater, Cathryn H. (eds.). "We Can Neither Confirm Nor Deny" Sentinels of History: Refelections on Arkansas Properties on the National Register of Historic Places. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press.

- ^ "Report on the Health Consequences to the American Population from Nuclear Weapons Tests Conducted by the United States and Other Nations". CDC. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ Exposure of the American Population to Radioactive Fallout from Nuclear Weapons Tests

- ^ What governments offer to victims of nuclear tests

- ^ Radiation Exposure Compensation System: Claims to Date Summary of Claims Received by 06/11/2009

- ^ Efron, Sonni (December 30, 1999). "System of Disposable Laborers". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Wald, Matthew L. (January 29, 2000). "U.S. Acknowledges Radiation Killed Weapons Workers". New York Times. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Iwaki, H.T. (October 8, 2012). "Meet the Fukushima 50? No, you can't". The Economist. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Bagne, Paul (November 1982). "The Glow Boys: How Desperate Workers are Mopping Up America's Nuclear Mess". Mother Jones. VII (IX): 24–27. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Efron, Sonny. "System of Disposable Laborers". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Petersen-Smith, Khury. "Twenty-first century colonialism in the Pacific". IRS. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Jacob, P.; Rühm, L.; Blettner, M.; Hammer, G.; Zeeb, H. (March 30, 2009). "Is cancer risk of radiation workers larger than expected?" (PDF). Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 66 (12): 789–796. doi:10.1136/oem.2008.043265. PMC 2776242. PMID 19570756. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Krolicki, Kevin and Chisa Fujioka. "Japan's "throwaway" nuclear workers". Reuters, MMN: Mother Nature Network. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Bureau of Labor Statistics. "Hazardous Materials Removal Workers". Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Cardis, E.; Vrijheid, M.; Blettner, M.; Gilbert, E.; Hakama, M.; Hill, C.; Howe, G.; Kaldor, J.; Muirhead, C. R.; Schubauer-Berigan, M.; Yoshimura, T.; Bermann, F.; Cowper, G.; Fix, J.; Hacker, C.; Heinmiller, B.; Marshall, M.; Thierry-Chef, I.; Utterback, D.; Ahn, Y-O.; Amoros, E.; Ashmore, P.; Auvinen, A.; Bae, J-M.; Bernar, J.; Biau, A.; Combalot, E.; Deboodt, P.; Sacristan, A. Diez; Eklöf, M.; Engels, H.; Engholm, G.; Gulis, G.; Habib, R. R.; Holan, K.; Hyvonen, H.; Kerekes, A.; Kurtinaitis, J.; Malker, H.; Martuzzi, M.; Mastauskas, A.; Monnet, A.; Moser, M.; Pearce, M. S.; Richardson, D. B.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Rogel, A.; Tardy, H.; Telle-Lamberton, M.; Turai, I.; Usel, M.; Veress, K. (April 2007). "The 15-Country Collaborative Study of Cancer Risk among Radiation Workers in the Nuclear Industry: Estimates of Radiation-Related Cancer Risks". Radiation Research: Official Journal of the Radiation Research Society. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 167 (4): 396–416. doi:10.1667/RR0553.1. PMID 17388693. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Martin, B. (2015). Nuclear power and civil liberties EnergyScience - The Briefing Paper 23 (pp. 1-6) Australia.

- ^ Welsome, Eileen (1999). The Plutonium Files: America's Secret Medical Experiments in the Cold War. New York, NY: Delta Books, Random House, Inc. ISBN 0-385-31954-1.