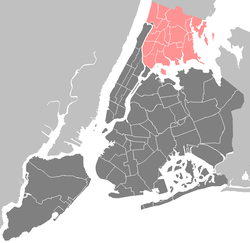

Co-op City, Bronx

Co-op City | |

|---|---|

Co-op City, as seen from the east, sits along the Hutchinson River. | |

| Coordinates: 40°52′26″N 73°49′46″W / 40.8738889°N 73.8294444°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | New York City |

| Borough | The Bronx |

| Constructed | 1973 |

| Named for | Short for Cooperative City |

| Area | |

• Total | 2.42 km2 (0.936 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Total | 43,752 |

| • Density | 18,000/km2 (47,000/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • White | 8.5% |

| • African-American | 60.5% |

| • Hispanic and Latino Americans | 27.7% |

| • Asian | 1.2% |

| • Other | 2.1% |

| Economics | |

| • Median income | $43,431 |

| ZIP code | 10475 |

| Area code(s) | 718, 347, 929, and 646 |

Co-op City (short for Cooperative City), located in the Baychester section of the borough of the Bronx in northeast New York City, is the largest cooperative housing development in the world.[4] Situated at the intersection of Interstate 95 and the Hutchinson River Parkway, the community is part of Bronx Community District 10. If it were a distinct municipality, it would be the 10th largest city in New York State. Nearby attractions include Pelham Bay Park, Orchard Beach and City Island. The community's Zip code is 10475.

Area description

Originally a swamp, the site was formerly the home of a 205-acre amusement park named Freedomland that operated from June 19, 1960[5][6] to September 1964.[7] Construction on Co-op City began in May 1966.[8] Residents began moving in during December 1968,[9] and construction was completed in 1973. Its 15,372 residential units, in 35 high rise buildings and seven clusters of townhouses, make it the largest single residential development in the United States.[10] It sits on 320 acres (1.3 km2) but only 20% of the land was developed, leaving many green spaces. The apartment buildings, referred to by number, range from 24 floors to as high as 33. There are four types of buildings; Triple Core (26 stories high with 500 apartment units per building), Chevron (24 stories; 414 units), Tower (33 stories; 414 units) and Town House. The 236 townhouses, referred to by their street-name cluster, are three stories high and have a separate garden apartment and upper duplex three-bedroom apartment.[11]

Co-op City is divided into five sections. Sections one to four are connected and section five is separated from the main area by the Hutchinson River Parkway. Each street in a section is denoted by a letter of the alphabet. All streets in section one begin with the letter "D", section two begins with the letter "C", section three with the letter "A", section four with the letter "B" and section five with the letter "E". Most streets in the community are named after notable historical personalities such as Earhart Lane for Amelia Earhart, Einstein Loop for Albert Einstein, Casals Place for Pablo Casals and Dreiser Loop for Theodore Dreiser.

This "city within a city" also has eight parking garages, three shopping centers, a 25-acre (100,000 m2) educational park, including a high school, two middle schools and three grade schools (the high school, Harry S. Truman High School, is unusual for having a planetarium on the premises), power plant, a 4-story air conditioning generator and a firehouse. More than 40 offices within the development are rented by doctors, lawyers, and other professionals and there are at least 15 houses of worship. Spread throughout the community are six nursery schools and day care centers, four basketball courts and five baseball diamonds. The adjacent Bay Plaza Shopping Center has a 13-screen multiplex movie theater, department stores, and a supermarket.

The development was built on landfill; the original marshland still surrounds it. The building foundations extend down to bedrock through 50,000 pilings,[12] but the land surrounding Co-op's structures settles and sinks a fraction of an inch each year, creating cracks in sidewalks and entrances to buildings.[13]

History

Development

Co-op City is on the site of Freedomland, a former amusement park which closed in 1964.[14] Prior to housing that theme park, the land north of the Hutchinson River Parkway was a large area known by residents as "the dump". By the '50s, most of the land on the north side of the Hutchinson River was flat land used for recreation; for example, model airplane flying meets were held there. It was possible to drive up to the Hutchinson River and walk along several paths through the reeds and swim in the Hutchinson River. The land to the south of the Hutchinson River (Section 5 of Co-op City) was unspoiled swamp land from the '50s up through the time Co-op City was constructed. A tidal estuary reached from the Hutchinson River at the New Haven Railroad along a route just north of Hunter and Boller Avenue to pass under the Hutchinson River parkway. The estuary was the site of boat yards and canoe rental sites during the 1950s. A well known restaurant at that site was Gus's Barge, operated by Gus and Francis Erickson. Gus's Barge was a restaurant and a night club featuring jazz combos and other forms of live music. The Ericksons also operated a boat yard that not only rented slips but specialized in refurbishing wooden boats, primarily motor boats made from teak and mahogany. The Ericksons sold their property in 1961–62.

The project was sponsored and built by the United Housing Foundation, an organization established in 1951 by Abraham Kazan and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. It was designed by cooperative architect Herman J. Jessor. The name of the complex's corporation itself was later changed to RiverBay at Co-op City.

The construction of the community was financed with a mortgage loan from New York State's Housing Finance Agency (HFA). The complex defaulted on the loan in 1975 and has had ongoing agreements to pay back HFA, until 2004 when it was financially unable to continue payments due to the huge costs of emergency repairs. New York Community Bank helped RiverBay satisfy its $57 million mortgage obligation, except for $95 million in arrears, by refinancing the loan later that same year. This led to the agreement that Co-op City would remain in the Mitchell-Lama Housing Program for at least seven more years as a concession on the arrears and that any rehabilitation that Co-op City took on to improve the original poor construction (which happened under the State's watch) would earn credit toward eliminating the debt. By 2008, RiverBay had submitted enough proof of construction repairs to pay off the balance of arrears to New York State.

Mismanagement, shoddy construction and corruption led to the community defaulting on its loan in 1975. The original Kazan board resigned and the state took over control. Cooperators were faced with a 25 percent increase in their monthly maintenance fees. Instead, a rent-strike was organized. New York State threatened to foreclose on the property, and evict the tenants — which would mean the loss of their equity. But Cooperators stayed united and held out for 13 months (the longest and largest rent-strike in United States history) before a compromise was finally reached, with mediation from then Bronx Borough President, Robert Abrams, and then Secretary of State, Mario Cuomo. Cooperators would remit $20 million in back pay, but they would get to take over management of the complex and set their own fees.[15]

The shares of stock that prospective purchasers bought to enable them to occupy Co-op City apartments became the subject of protracted litigation culminating in a United States Supreme Court decision United Housing Foundation, Inc. v. Forman, 421 U.S. 837 (1975).

Renovation era

Within the first decade of the 2000s, the aging development began undergoing a complex-wide $240 million renovation, replacing piping and garbage compactors, rehabilitating garages and roofs, upgrading the power plant, making facade and terrace repairs, switching to energy-efficient lighting and water-conserving technologies, replacing all 130,000 windows and 4,000 terrace doors (costing $57.9 million in material and labor) and all 179 elevators. The word "renaissance" is being used to describe this period in Co-op City history. Many of these efforts are also helping in the "greening" of the complex: the power-plant will be less polluting, the buildings will be more efficient and recycling efforts will become more extensive. The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) awarded its largest ever grant—$5.2 million—to the community under its NY Energy $mart Assisted Multifamily Program.

In 2003, after a partial collapse in one garage, inspectors found 5 of the 8 garages to be unsafe and ordered them closed for extensive repairs. The other 3 garages were able to remain partially open during repairs. To deal with the parking crisis, New York City allowed angled parking in the community, the large greenways in the complex were paved over to make outdoor parking lots and agreements were made with nearby shopping centers to use their extra parking spaces. January 2008 was the first time in over 41⁄2 years that all the garages were back open. The greenways are in the process of being restored.

Financial responsibility for these upgrades was the subject of a protracted dispute between RiverBay and the State of New York.[16] Co-op City was developed under New York's Mitchell-Lama Program, which subsidizes affordable housing. RiverBay charged that the state should help with the costs because of severe infrastructure failures stemming from the development's original shoddy construction, which occurred under the supervision of the state. The state countered that RiverBay was responsible for the costs because of its lack of maintenance over the years. In the end, a compromise had the state supplying money and RiverBay refinancing the mortgage, borrowing $480 million from New York Community Bank in 2004, to cover the rest of the capital costs.[17]

In 2007, the power plant was in the process of upgrading from solely managing the electricity brought in from Con Edison to a 40-megawatt tri-generation facility with the ability to use oil, gas or steam (depending on market conditions) to power turbines to produce its own energy. The final cost of this energy independence could be as much as $90 million, but it is hoped to pay for itself with the savings earned—with conservative estimates at $18 million annually—within several years. Also, whatever excess power generated after satisfying the community's needs will be sold back to the electrical grid, adding another source of income for RiverBay.

In September 2007, a report by the New York Inspector General, Kristine Hamann, charged that the Division of Housing and Community Renewal (DHCR), which is responsible for overseeing Mitchel-Lama developments, was negligent in its duties to supervise the contracting, financial reporting, budgeting and the enforcement of regulations in Co-op City (and other M-L participants) during the period of January 2003 to October 2006. The report also chided Marion Scott management for trying to influence the RiverBay Board by financing election candidates and providing jobs and sports tickets to Board members and their family/friends—all violations of DHCR and/or RiverBay regulations. The DHCR was instructed to overhaul its system of oversight to better protect the residents and taxpayer money.[18]

In October 2007, a former board president, Iris Herskowitz Baez, and a former painting contractor, Nickhoulas Vitale, pleaded guilty to involvement in a kickback scheme. While on the RiverBay Board, Baez steered $3.5 million in subsidized painting contracts for needed work in Co-op City apartments, to Vitale's company, Stadium Interior Painting, in exchange for $100,000 in taxpayer money.[19] Ms. Herskowitz Baez was sentenced to 6 months in jail, 12 months probation and given a $10,000 fine in March 2008.[20]

Management

RiverBay Corporation is the corporation that operates the community and is led by a 15-member board of directors. As a cooperative development, the tenants run the complex through this elected board. There is no pay for serving on the board. The corporation employs over 1000 people and has 32 administrative and operational departments to serve the development.

The complex has its own Public Safety Department with more than 100 sworn officers, which include field patrol, plainclothes detectives and EMT/AED certified members of the force. All members have also attained peace officer status by NY State because of their special training. In December 2007, the cable television company Cablevision gave RiverBay permission to use its fiber optic cables in order to install additional surveillance cameras throughout the complex to be viewed at the Public Safety Command Center. In 2008, trained supervisors were granted the power to write summonses for parking and noise violations and Segways were acquired–along with bikes–to help the officers patrol during the warmer months.

Co-op City was managed by Marion Scott Real Estate, Inc. from October 1999 to November 2014. Before then the property was run by in-house general managers. The development is currently managed by Douglas Elliman Property Management.

There are two weekly newspapers serving the community: Co-op City Times (the official RiverBay paper) and City News.

Qualifications for resident application

As of November 2007 those who wish to move into Co-op City must meet the following requirements:

- Must not have felony conviction(s)[21]

- Credit score of at least 650 for the one-bedroom and 700 for the two- and three-bedroom apartments

- Must not belong to the Section 8 program

- Must not have another primary residence

- Be subject to a home visit during the application process[21]

- Depending on the number of rooms and occupants

Sales prices:

- One-bedroom – $13,500–$18,000

- two-bedrooms – $20,250–$22,500

- three-bedrooms – $27,000–$29,250[21]

Income requirement:

- One-bedroom – $23,160 minimum/$75,768 maximum

- Two-bedrooms – $34,760 minimum/$108,240 maximum

- Three-bedrooms – $46,320 minimum/$140,760 maximum

- Seniors have a reduced minimum income of between $20,844 and $45,180[21]

Monthly maintenance:

- One-bedroom – $579–$772

- two-bedrooms – $869–$965

- three-bedrooms – $1,158–$1,255[21]

Security

The Co-op City Department of Public Safety, a private public safety force, enforces state and city laws on Co-op City property in order to protect them. The Co-op City Department of Public Safety currently employs more than 100 Public Safety officers and 10 civilian employees.[22][23][24]

Demographics

Based on data from the 2010 United States Census, the population of Co-Op City was 43,752, an increase of 3,076 (7.6%) from the 40,676 counted in 2000. Covering an area of 857.55 acres (347.04 ha), the neighborhood had a population density of 51.0 inhabitants per acre (32,600/sq mi; 12,600/km2).[2]

The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 8.5% (3,723) White, 60.5% (26,452) African American, 0.2% (108) Native American, 1.2% (522) Asian, 0.0% (7) Pacific Islander, 0.3% (125) from other races, and 1.6% (681) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 27.7% (12,134) of the population.[3]

Because of its large senior citizen block—well over 8,300 residents above the age of sixty as of 2007[25]—it is considered the largest naturally occurring retirement community (NORC) in the nation and its Senior Services Program has extensive outreach to help its aging residents, most of whom moved in as workers and remained after retiring.[26]

Co-op City was home to a large Jewish community during its early years, as well as Italian Americans and Irish Americans; many of them had relocated from other areas of the Bronx, such as the Grand Concourse. With African Americans making up a large minority, the community became known for its ethnic diversity. As early tenants grew older and moved away, the newer residents reflected the current population of the Bronx, with African American and Hispanic residents comprising the majority of residents by 1987.[27] In the 1990s, after the fall of the Soviet Union, the neighborhood received an influx of former Eastern Bloc émigrés, especially from Russia and Albania.[28]

Transportation

Co-op City is served by New York City Bus routes Bx5, Bx12, Bx26, Bx28, Bx29, Bx30, and MTA Bus routes Bx23, Q50, BxM7.[29] These local city buses, with the exception of the BxM7, which is an express bus to Manhattan, connect Co-op City with subway services. While there are no subway or Metro-North commuter rail stations in Co-op City (a plan to extend the IRT Pelham Line to Co-op City as part of the 1968 Program for Action ran out of money[30][31]), the MTA is planning to extend Metro-North service to Penn Station, and included in that plan is a station at Co-op City, an idea that has been proposed since the 1970s.

In popular culture

- On their 1996 album Factory Showroom, the band They Might Be Giants released a cover of a song called "New York City" (originally by a Canadian band named Cub). In their version, TMBG changed the lyric "Alphabet City" to "Co-op City".

- Robert Klein sings that the Bronx is beautiful and specifically mentions Co-op City in "The Traveling Song".

- The hip-hop song "Sometimes I Rhyme Slow" by Nice & Smooth, released 1991 on the album Ain't a Damn Thing Changed, contains the lyric "I go to Bay Plaza and catch a flick". Bay Plaza is a large shopping mall adjacent to Co-op City, with a 13-screen movie theater owned and operated by AMC Theatres.

- In the Dark Tower novels by Stephen King, the character Eddie Dean is portrayed as being from Co-op City. In Dean's first appearance, in the second book, The Drawing of the Three, Co-op City is correctly identified as being in the Bronx, while in later novels it is incorrectly portrayed as being in Brooklyn. Central to the series is the concept of alternate realities, so in some such realities Co-op City may have been in Brooklyn. King rectifies the discrepancy in the final novels of the series.

- In the season-seven episode "Gone" of Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, the detectives' search for the body of a murdered witness leads them to a river in Co-op City.

- The novel Bloodbrothers by Richard Price takes place in Co-op City at a fictional address. Price's novel Freedomland takes its title from the amusement park that previously occupied the site.

- The opening titles of the film Finding Forrester shows scenes in and around Co-op City.

- The end of the film The Seven-Ups depicts areas just outside Co-op City's Section Five.

- An episode of Queer Eye For The Straight Guy was briefly filmed in Co-op City. The segment featured notable signage found in the community.

- Co-op City was featured in the second-season episode "Home Wrecked Home" of Life After People: The Series.

- A fictional representation of Co-op City named "Northern Gardens" is included in Grand Theft Auto IV's "Bohan", based on the Bronx.

Notable residents

- Brian Ash (born 1974), screenwriter/producer (resided in Co-op City from 1974 to 1993)[citation needed]

- Earl Battey (1935-2003), former baseball player with the Chicago White Sox and Washington Senators (later renamed the Minnesota Twins).[32]

- David Berkowitz (born 1953), "Son of Sam" Killer (resided in Co-op City from 1968 to 1971)[33]

- Big Tigger (born 1972), radio and television personality[34]

- Kurtis Blow (born 1959), old school hip hop pioneer (resided in the Broun Place Townhouses during the mid-1980s)[35]

- Christopher Scott Cherot, screenwriter/director (resided in Co-op City from 1970 to 1981)[36]

- Cormega (born 1970), rapper[37]

- Eliot Engel (born 1947), United States Congressman who represents New York's 17th congressional district.[38]

- Stan Jefferson (born 1962), professional baseball player from 1986 to 1991.[39]

- Queen Latifah (born 1970), actress and rapper (resided in Co-op City from 1980 to 1984)[35]

- Miles Marshall Lewis (born 1970), African-American author (resided in Co-op City from 1974 to 1996)[40]

- Richard Price (born 1949), novelist and screenwriter.[41]

- Sally Regenhard – mother of firefighter Christian Regenhard, and activist for families of the victims of the September 11 terrorist attacks.[42]

- Larry Seabrook – former New York City councilman[43]

- Sonia Sotomayor (born 1954), Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court[44][45]

- Rod Strickland (born 1966), former NBA basketball player[citation needed]

- Kenneth P. Thompson (1966-2016), former District Attorney for Kings County [46]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Coop City neighborhood in New York". Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Table PL-P5 NTA: Total Population and Persons Per Acre - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- ^ a b Table PL-P3A NTA: Total Population by Mutually Exclusive Race and Hispanic Origin - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, March 29, 2011. Accessed June 14, 2016.

- ^ "Urban Mass: A Look at Co-op City", The Cooperator. Accessed December, 2006.

- ^ "Amusement Park Opens in Bronx; Tells US History". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. June 20, 1960. p. 16.[dead link]

- ^ "25,000 Tons of Cooling for Complex". Beaver County TImes. Beaver County, Pennsylvania. United Press International. December 12, 1967. p. B-7.

- ^ "Freedomland Aides Get Paychecks Back". The New York Times. September 9, 1964.

- ^ Evans Asbury, Edith (May 15, 1966). "Ground Broken for Bronx Co-ops". The New York Times. p. 70.

- ^ "News Briefs". The Sumter Daily Item. Sumter, South Carolina. Associated Press. November 25, 1968. p. 7A.

- ^ A Walk Through the Bronx, WNET. Accessed June 18, 2007. "Co-op City is a middle income cooperative located in the northeastern corner of the Bronx and is it the largest single residential development in the United States. Completed in 1971, it consists of 15,372 residential units, in thirty-five high-rise buildings and seven clusters of townhouses."

- ^ Cheslow, Jerry. "If You're Thinking of Living In/Co-op City; A City, Bigger Than Many, Within a City", The New York Times, November 20, 1994. Accessed September 28, 2017. "There are four building styles in Co-op City: the 26-story Triple Core, which has three entrances and 500 units; the 24-story Chevron, with 414 units; the 33-story, 384-unit Tower, and the three-story town-house buildings, with one-bedroom apartments on the ground floor and three-bedroom units on the other floors. In all, there are 35 high-rise buildings and seven town-house clusters, some of which have two, some three, buildings."

- ^ Cheslow, J. "If You're Thinking of Living In/Co-op City" New York Times, November 20, 1994.

- ^ Puza, D, and Breslin, R, "Saving a Sinking City" Civil Engineering—ASCE, Vol. 67, No. 2, February 1997, pp. 48–51

- ^ Elsa Brenner (2008-04-06). "Evereything you need, in one giant package". New York Times.

- ^ "Bronx Odyssey: From Rebel to Executive to Felon", The New York Times, October 10, 2006. Accessed October 10, 2006.

- ^ "Co-op City secures $480m loan to pay mortgage, finance repairs" New York TImes. Accessed September 15, 2004. "Many of the needed repairs stem from construction-related defects, and Co-op City residents and state officials have been arguing for years over who should pay for them."

- ^ "Residential Real Estate; Co-op City Hires Outside Managers" The New York Times. Accessed November 5, 1999

- ^ "An In-Depth Review of the Division of Housing and Community Renewal’s Oversight of the Mitchell-Lama Program". State of New York Office of the Inspector General. September 2007

- ^ Cornell, Kati. "PAINT MISBEHAVIN' AT CO-OP", The New York Post, October 19, 2007. Accessed January 20, 2008.

- ^ "FORMER CO-OP CITY BOARD PRESIDENT SENTENCED TO JAIL TIME FOR ACCEPTING KICKBACK PAYMENTS", United States Attorney Southern District of New York, MARCH 2008

- ^ a b c d e "2009 Suggested Application effective January 2010" (PDF). RiverBay Corporation. January 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Uniformed Patrol". ccpd.us. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ "Community Policing". ccpd.us. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ "Organization". ccpd.us. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ "Identifying Risks to Healthy Aging in New York City’s Varied NORCs – NORC Program Characteristics, 2007" "Fredda Vladeck and Rebecca Segel, United Hospital Fund". Accessed August 14, 2013

- ^ "Haven for Workers in Bronx Evolves for Their Retirement" The New York Times. Accessed August 5, 2002

- ^ "Co-op City Sets New Goal: Attract More Whites" The New York Times. November 30, 1987.

- ^ "Urban Mass: A Look at Co-op City" The Cooperator: The Co-op & Condo Monthly. December 2006

- ^ "Bronx Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ nycsubway.org—The New York Transit Authority in the 1970s

- ^ nycsubway.org—The New York Transit Authority in the 1980s

- ^ Peterson, Armand. "Stan Jefferson", Society for American Baseball Research. Accessed September 28, 2017. "Jefferson’s baseball exploits attracted the attention of Earl Battey, the four-time All-Star catcher with the Minnesota Twins in the 1960s. Battey was also a resident of Co-op City and since 1968 had been running the Con Ed Answer Man community relations program for Consolidated Edison of New York."

- ^ Case File: David Berkowitz Retrieved June 17, 2009

- ^ Radar: Big Tigger, SixShot.Com, date December 27, 2007, Retrieved June 17, 2009

- ^ a b On Da Come Up with Clap Cognac, HipHopRuckus.com, date February 24, 2009. Retrieved June 13, 2009

- ^ AN INTERVIEW WITH FILMMAKER CHRISTOPHER SCOTT CHEROT from The New Times Holler, April 7, 2008. Accessed June 13, 2009

- ^ Golianopoulos, Thomas. "The Bridge Is Over; The Queensbridge Houses were once at the center of the rap universe. What happened to hip-hop's most storied housing project? ", Complex (magazine), November 25, 2014. Accessed July 16, 2017. "Born Cory McKay in Brooklyn, Cormega moved at an early age from Bedford-Stuyvesant to Co-Op City in the Bronx where he lived on a 22nd floor apartment with a balcony."

- ^ Stanley, Alessandra. "Out of Cell (and Sickbed), Biaggi Tries Anew", The New York Times, September 12, 1992. Accessed July 16, 2017. "Mr. Engel, 45, a former teacher and State Assemblyman who grew up in Co-op City, where he still lives, is so subdued and unflamboyant that on Capitol Hill, where he serves on the Foreign Affairs Committee, he is sometimes mistaken for a Congressional aide."

- ^ Coffey, Wayne. Former Met Stanley Jefferson struggles to cope with horror of life as 9/11 cop", New York Daily News, March 9, 2007. Accessed June 18, 2007.

- ^ Akashic Books: Miles Marshall Lewis, from www.akashicbooks.com

- ^ Vanderbilt, Tom. "CITY LORE; Stagecoach Wreck Injures 10 in Bronx", The New York Times, September 1, 2002. Accessed September 28, 2017. "After a few years, the world's largest theme park, and New York's last, gave way to the world's largest housing development, Co-op City. Mr. Price, who joined the electrical workers' union, helped build it.... A year later, Mr. Price got an apartment in Co-op City: I wound up living in Freedomland, so to speak."

- ^ Gest, Emily. "9/11 SURVIVORS FEEL DUTY TO KIN Mission of remembrance a cornerstone of their lives", New York Daily News, August 5, 2002. Accessed June 6, 2016. "ally Regenhard, of Co-op City in the Bronx, who lost her son Christian, a firefighter, has quit her two jobs at nursing homes to devote herself full-time to her passion - improving skyscraper safety."

- ^ "New York City Council: Larry Seabrook". Council.nyc.gov. Retrieved 2011-06-14.

- ^ My Beloved World, 2013 Knopf, Chapter 11

- ^ Sonia Sotomayor: At Last a Bronx Candidate! Concurring Opinions, date May 2009. Accessed June 17, 2009.

- ^ Feuer, Alan. "For Brooklyn’s District Attorney, Year One Is a Trial by Fire", The New York Times, March 13, 2015. Accessed September 28, 2017. "He also noted that although he was raised in the Robert Wagner Houses, his mother, Clara, eventually moved the family to Co-op City in the Bronx, where they did not live in Section 5 — 'where the black folk live,' he said — but in Section 2, where he spent his teenage years as a bookworm and a paperboy for his neighbors, most of whom were Jewish."