List of largest stars

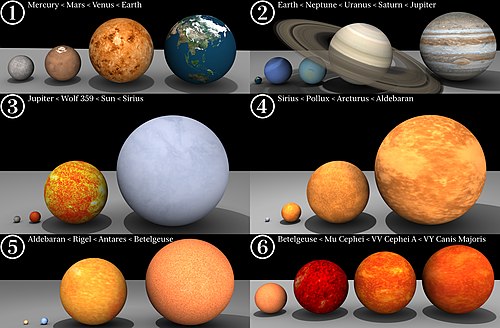

- Mercury < Mars < Venus < Earth

- Earth < Neptune < Uranus < Saturn < Jupiter

- Jupiter < Proxima Centauri < Sun < Sirius

- Sirius < Pollux < Arcturus < Aldebaran

- Aldebaran < Rigel < Antares < Betelgeuse

- Betelgeuse < Mu Cephei < VV Cephei A < VY Canis Majoris

Below is an ordered list of the largest stars currently known by radius. The unit of measurement used is the radius of the Sun (approximately 695,700 km; 432,288 mi).

The exact order of this list remains very incomplete, as there currently remains great uncertainties especially when deriving various important parameters used in calculations, such as stellar luminosity and effective temperature. Often stellar radii can only be expressed as an average or within a large range of values. Values for stellar radii do vary significantly in sources and throughout the literature, mostly as the boundary of the very tenuous atmosphere (opacity) greatly differs depending on the wavelength of light in which the star is observed.

Several stars can have their radii directly obtained by stellar interferometry. Other methods can use lunar occultations or from eclipsing binaries, which can be used to test other indirect methods of determining true stellar size. Only a few useful supergiant stars can experience occultations by the Moon, including Antares and Aldebaran. Examples of eclipsing binaries include Epsilon Aurigae, VV Cephei, HR 5171, and the red-giant binary system KIC 9246715 in the constellation of Cygnus.[1]

Caveats

Complex issues exist in determining the true radii of the largest stars, which in many cases do display significant errors. The following lists are generally based on various considerations or assumptions that include:

- Largest stars are usually expressed in units of the solar radius (R☉), where 1.00 R☉ equals 695,700 kilometres.

- Stellar radii or diameters are usually only approximated using Stefan–Boltzmann law for the deduced stellar luminosity and effective surface temperature;

- Stellar distances, and their errors, for most, remain uncertain or poorly determined;

- Many supergiant stars have extended atmospheres and many are embedded within opaque dust shells, making their true effective temperatures highly uncertain;

- Many extended supergiant atmospheres also significantly change in size over time, regularly or irregularly pulsating over several months or years as variable stars. This makes adopted luminosities poorly known and may significantly change the quoted radii;

- Other direct methods for determining stellar radii, rely on lunar occultations or from eclipses in binary systems. This is only possible for a very small number of stars;

- Based on various theoretical evolutionary models, few stars will exceed 1,500–2,000 times the Sun (roughly 3,715 K and Mbol = −9). Such limits maybe also depend on the stellar metallicity.[2]

Extragalactic large stars

Included within this list are some examples of more distant extragalactic stars, which may have slightly different properties and natures than the currently largest known stars in the Milky Way:

- Some red supergiants in the Magellanic Clouds are suspected to have slightly different limiting temperatures and luminosities. Such stars may exceed accepted limits by undergoing large eruptions or change their spectral types over just a few months. Humphreys et al., for example, calculates the maximum size for a Magellanic cloud star as ~2,600 R☉.[citation needed]

- A survey of the Magellanic Clouds have catalogued many red supergiants, where more than 50 of them exceed 700 R☉ (490,000,000 km; 3.3 AU; 300,000,000 mi). Largest of these is about 1,200-1,300 R☉.[3]

List

| Star name | Solar radii (Sun = 1) |

Method | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| VY Canis Majoris[4] | (1,420[5]–) 2,200[6][7] | AD | The upper estimate is so large that places it outside the bounds of stellar evolutionary theory. Improved measurements have brought it down to size by giving the lower estimate.[5][6] This star is a red hypergiant, although Massey et al. considered it as a normal red supergiant with a radius of only 600 R☉.[8] Margin of possible error: ± 120 solar radii (Wittkowski 2012). |

| Orbit of Saturn | 1,940–2,169 | Reported for reference | |

| VV Cephei A | (1,050[9]–) 1,900[2] | VV Cep A is a highly distorted star in a close binary system, losing mass to the secondary for at least part of its orbit. Other estimates give radii of 1,200 R☉ to 1,600 R☉[2][10] or 1,400 R☉[11]. | |

| UY Scuti | 1,708 ± 192[12] | AD | Margin of error in size determination: ±192 solar radii. At the smallest, it would have a size similar to VX Sagittarii (see below) |

| NML Cygni | 1,640,[13] 1,183[14]–2,770[13] | L/Teff | |

| WOH G64 | 1,540[15]–1,730[16] | L/Teff | This would be the largest star in the LMC, but is unusual in position and motion and might still be a foreground halo giant. |

| RW Cephei | 1,535 [17][18] | L/Teff | RW Cep is variable both in brightness (by at least a factor of 3) and spectral type (observed from G8 to M), thus probably also in diameter. Because the spectral type and temperature at maximum luminosity are not known, the quoted size is just an estimate. |

| Westerlund 1-26 | 1,530-1,580[19] (–2,550) [20] | L/Teff | Very uncertain parameters for an unusual star with strong radio emission. The spectrum is variable but apparently the luminosity is not. |

| VX Sagittarii | 1,520[21] | L/Teff | VX Sgr is a pulsating variable with a large visual range from 1,350 R☉ to 1,940 R☉ and varies significantly in size.[22] |

| V354 Cephei | 1,520[2] | L/Teff | Mauron (2011) derive 76,000 L☉, which implies a size around 690 R☉.[21] |

| KY Cygni | 1,420–2,850 [2] | L/Teff | The upper estimate is due to an unusual K band measurement and thought to be an artifact of a reddening correction error, and is thought to be against stellar evolutionary theory. The lower estimate is consistent with other stars in the same survey and with theoretical models. |

| AH Scorpii | 1,411 ± 124[12] | AD | AH Sco is variable by nearly 3 magnitudes in the visual range, and an estimated 20% in total luminosity. The variation in diameter is not clear because the temperature also varies. |

| RSGC1-F02 | 1,398[23] | L/Teff | |

| RSGC1-F01 | 1,335[23] | L/Teff | |

| HR 5171 A | 1,315 ± 260,[24] 1,575 ± 400[25] | AD | HR 5171 A is a highly distorted star in a close binary system, losing mass to the secondary, and is also variable in temperature, thus probably also in diameter. Traditionally, it is considered as the largest known yellow hypergiant, although the latest research suggests it is a red supergiant with a radius 1,490 ± 540 R☉.[26] |

| SMC 18136 | 1,310[3] | This would be the largest star in the SMC. | |

| PZ Cassiopeiae | 1,260-1,340,[27] 1,190-1,940[2] | L/Teff | The largest estimate is due to an unusual K band measurement and thought to be an artifact of a reddening correction error. The lowest estimate is consistent with other stars in the same survey and with theoretical models, and the intermediate ones have been obtained refining the distance to this star, and thus its parameters. |

| Mu Cephei (Herschel's "Garnet Star") | 1,260[28] | Reddest star in the night sky.[29] Other recent estimates range from 650 R☉[30] to 1,420 R☉[2] | |

| LMC 136042 | 1,240[3] | ||

| BI Cygni | 1,240[2] | L/Teff | |

| Westerlund 1-237 | 1,233[20] | L/Teff | Calculated from an effective temperature of 3,600 K and a luminosity of 230,000 L☉.[20] |

| SMC 5092 | 1,220[3] | ||

| S Persei | 1,212 ± 124[31] | AD & L/Teff | A red hypergiant localed in the Perseus Double Cluster. A large radius of 1,230 R☉ is due to an unusual K band measurement and thought to be an artifact of a reddening correction error. A small radius of 780 R☉ is consistent with other stars in the same survey and with theoretical models.[2] |

| LMC 175464 | 1,200[3] | ||

| LMC 135720 | 1,200[3] | ||

| RAFGL 2139 | 1,200[32] | RAFGL 2139 is a rare red supergiant companion to WR 114 that has a bow shock. | |

| SMC 69886 | 1,190[3] | ||

| RSGC1-F05 | 1,177[23] | L/Teff | |

| EV Carinae | 1,168[33]-2,880[34] | L/Teff | |

| RSGC1-F03 | 1,168[23] | L/Teff | |

| LMC 119219 | 1,150[3] | ||

| RSGC1-F08 | 1,146[23] | L/Teff | |

| BC Cygni | 1,140[2]-1,230[28] | L/Teff | Other recent estimates range from 856 R☉ to 1,553 R☉.[35] |

| SMC 10889 | 1,130[3] | ||

| LMC 141430 | 1,110[3] | ||

| LMC 175746 | 1,100[3] | ||

| RSGC1-F13 | 1,098[23] | L/Teff | |

| RT Carinae | 1,090[2] | L/Teff | |

| RSGC1-F04 | 1,082[23] | L/Teff | |

| LMC 174714 | 1,080[3] | ||

| LMC 68125 | 1,080[3] | ||

| SMC 49478 | 1,080[3] | ||

| SMC 20133 | 1,080[3] | ||

| V396 Centauri | 1,070[2] | L/Teff | |

| SMC 8930 | 1,070[3] | ||

| Orbit of Jupiter | 1,064–1,173 | Reported for reference | |

| HV 11423 | 1,060–1,220[36] | L/Teff | HV 11423 is variable in spectral type (observed from K0 to M5), thus probably also in diameter. In October 1978, it was a star of M0I type. |

| CK Carinae | 1,060[2] | L/Teff | |

| SMC 25879 | 1,060[3] | ||

| LMC 142202 | 1,050[3] | ||

| LMC 146126 | 1,050[3] | ||

| LMC 67982 | 1,040[3] | ||

| U Lacertae | 1,022[21] | L/Teff | |

| RSGC1-F11 | 1,015[23] | L/Teff | |

| LMC 143877 | 1,010[3] | ||

| KW Sagittarii | 1,009[12]-1,460[2] | AD & L/Teff | Margin of possible error: ± 142 solar radii (Torres 2013). |

| SMC 46497 | 990[3] | ||

| LMC 140296 | 990[3] | ||

| RSGC1-F09 | 986[23] | L/Teff | |

| NR Vulpeculae | 980[2] | L/Teff | |

| SMC 12322 | 980[3] | ||

| LMC 177997 | 980[3] | ||

| SMC 59803 | 970[3] | ||

| GCIRS 7 | 960 ± 92[37] | AD | |

| Betelgeuse (Alpha Orionis) | 955 ± 217[38] | AD | Other recent estimates range from 887 ± 203 R☉[39] to 1,180 R☉[40] |

| SMC 50840 | 950[3] | ||

| RSGC1-F10 | 931[23] | L/Teff | |

| S Cassiopeiae | 930[41][42] | ||

| IX Carinae | 920[2] | L/Teff | |

| HV 2112 | 916[43] | L/Teff | Most likely candidate for a Thorne-Zytkow Object. |

| RSGC1-F07 | 910[23] | L/Teff | |

| LMC 54365 | 900[3] | ||

| NSV 25875 | 891[14] | L/Teff | |

| LMC 109106 | 890[3] | ||

| RSGC1-F06 | 885[23] | L/Teff | |

| LMC 116895 | 880[3] | ||

| SMC 30616 | 880[3] | ||

| LMC 64048 | 880[3] | ||

| V437 Scuti | 874[14] | L/Teff | |

| V602 Carinae | 860[2]-1,050[44] | L/Teff & AD | Margin of possible error: ± 165 solar radii (Torres 2015). |

| V669 Cassiopeiae | 859[14] | L/Teff | |

| SMC 55681 | 850[3] | ||

| SMC 15510 | 850[3] | ||

| LMC 61753 | 830[3] | ||

| LMC 62090 | 830[3] | ||

| SMC 11709 | 830[3] | ||

| V1185 Scorpii | 830[14] | L/Teff | |

| Outer limits of the asteroid belt | 816 | Reported for reference | |

| LMC 142199 | 810[3] | ||

| LMC 134383 | 800[3] | ||

| BO Carinae | 790[2] | L/Teff | |

| LMC 142907 | 790[3] | ||

| SU Persei | 780[2] | L/Teff | In the Perseus Double Cluster |

| RS Persei | 770[45]-1,000[2] | AD & L/Teff | In the Perseus Double Cluster. Margin of possible error: ± 30 solar radii (Baron 2014). |

| AV Persei | 770[2] | L/Teff | In the Perseus Double Cluster |

| V355 Cepheus | 770[2] | L/Teff | |

| V915 Scorpii | 760[46] | L/Teff | |

| S Cephei | 760[47] | ||

| SMC 11939 | 750[3] | ||

| HD 303250 | 750[2] | ||

| V382 Carinae | 747[48] | The brightest yellow hypergiant in the night sky, one of the rarest types of star. Achmad (1992) calculates 600 R☉ to 1,100 R☉ or 700 ± 250 R☉.[49] | |

| RU Virginis | 742[47] | ||

| LMC 137818 | 740[3] | ||

| SMC 48122 | 740[3] | ||

| SMC 56732 | 730[3] | ||

| V648 Cassiopeiae | 710[2] | L/Teff | |

| XX Persei | 710[50] | L/Teff | Located in the Perseus Double Cluster and near the border with Andromeda. |

| TV Geminorum | 620-710[51] (–770)[2] | L/Teff | |

| HD 179821 | 704[52] | A yellow hypergiant, although most authors consider it as a supergiant, a protoplanetary nebula or a post-AGB star with a luminosity of only 16,000 L☉. | |

| LMC 169754 | 700[3] | ||

| LMC 65558 | 700[3] | ||

| V528 Carinae | 700[2] | L/Teff | |

| The following well-known stars are listed for the purpose of comparison. | |||

| Antares A (Alpha Scorpii A) | 680[53] | AD | This star appears to vary its size by 165 R☉. Older estimates have given radii over 800 R☉,[54][55] but some are likely to have been affected by asymmetry of the atmosphere and the narrow range of infrared wavelengths observed.[53] Other recent estimates range from 653 R☉[56] to 1,246 R☉.[57] |

| CE Tauri | 587–593[58] (–608[59]) | Second reddest star in the night sky.[29] Can be occulted by the Moon, allowing accurate determination of its apparent diameter. | |

| R Leporis (Hind's "Crimson Star") | 400[60]–535[61] | Margin of possible error: ± 90 solar radii. | |

| Rho Cassiopeiae | 400-500[62] | Yellow hypergiant, one of the rarest types of a star. | |

| Inner limits of the asteroid belt | 412 | Reported for reference | |

| Mira A (Omicron Ceti) | 332–402[63] | Prototype Mira variable. De beck (2005) calculates 541 R☉.[14] | |

| V509 Cassiopeiae | 400–900[64] | Yellow hypergiant, one of the rarest types of a star. | |

| CW Leonis | 390–500,[65] 700[66]–826[14] | L/Teff | CW Leonis is one of the mistaken identities as the claimed planet "Nibiru" or "Planet X", due to its brightness as it approaches 1st magnitude. |

| V838 Monocerotis | 380 (in 2009)[67] | A short time after the outburst V838 Mon was measured at 1,570 ± 400 R☉.[68] However the distance to this "L supergiant", and hence its size, have since been reduced and it proved to be a transient object that shrunk about four-fold over a few years. | |

| S Doradus | 100-380[69] | Prototype S Doradus variable | |

| R Doradus | 370 ± 50[70] | Star with the second largest apparent size after the Sun. | |

| IRC +10420 | 357[71]–1,342[14] | L/Teff | A yellow hypergiant that has increased its temperature into the LBV range. |

| The Pistol Star | 340[72] | Blue hypergiant, among the most massive and luminous stars known. | |

| La Superba (Y Canum Venaticorum) | 307[14]-390[73] | L/Teff | Referred to as La Superba by Angelo Secchi. Currently one of the coolest and reddest stars. |

| Solar System Habitable Zone | 305 | Reported for reference | |

| Orbit of Mars | 297–358 | Reported for reference | |

| Alpha Herculis (Ras Algethi) | 284 ± 60[74] | Moravveji et al also gives a range from 264 R☉ to 303 R☉. At an estimated distance of 110 parsecs from the Sun, this corresponds to a radius of 400 ± 61 R☉.[74] | |

| Sun's red giant phase | 256[75] | The core hydrogen would be exhausted in 5.4 billion years. In 7.647 billion years, The Sun would reach the tip of the red-giant branch of the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram. (see below) Reported for reference | |

| Eta Carinae A (Tseen She) | 250,[76] 60–800[77] | Previously thought to be the most massive single star, but in 2005 it was realized to be a binary system. Other estimates gives 85 R☉ to 195 R☉.[78] | |

| Orbit of Earth | 211–219 | Reported for reference | |

| Deneb (Alpha Cygni) | 203 ± 17[79] | ||

| LBV 1806-20 | 200[80] | Formerly a candidate for the most luminous star in the Milky Way. | |

| Orbit of Venus | 154–157 | Reported for reference | |

| Epsilon Aurigae A (Almaaz) | 143-358[81] | ε Aur was incorrectly hailed as the largest star with a radius 2,000 R☉ or 3,000 R☉,[82] even though it later turned out not to be an infrared light star but rather a dusk torus surrounding the system. | |

| Peony Nebula Star | 92[83] | Candidate for most luminous star in the Milky Way. | |

| Rigel A (Beta Orionis A) | 78.9[84]–115[85] | Margin of possible error: ±7.4 solar radii. | |

| Canopus (Alpha Carinae) | 71 ± 4[86] | Second brightest star in the night sky. | |

| Orbit of Mercury | 66–100 | Reported for reference | |

| Aldebaran (Alpha Tauri) | 44.13 ± 0.84[87] | ||

| Polaris (Alpha Ursae Minoris) | 37.5[88] | The current northern pole star. | |

| R136a1 | 35.4[89] | Also on record as the most massive and luminous star known. | |

| Arcturus (Alpha Boötis) | 25.4 ± 0.2[90] | Brightest star in the northern hemisphere. | |

| HDE 226868 | 20-22[91] | The supergiant companion of black hole Cygnus X-1. The black hole is 500,000 times smaller than the star. | |

| VV Cephei B | 13[10]-25[92] | The B-type main sequence companion of VV Cephei A. | |

| Sun's helium burning phase | 10 | After the red-giant branch the Sun has approximately 120 million years of active life left. Reported for reference | |

| Sun | 1 | The largest object in the Solar System. Reported for reference | |

See also

References

- ^ Hełminiak, K.G.; Ukita, N.; Kambe, E.; Konacki, M. (2015). "Absolute Stellar Parameters of KIC 09246715: A Double-giant Eclipsing System with a Solar-like Oscillator". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 813 (2): L25. arXiv:1509.03340. Bibcode:2015ApJ...813L..25H. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/813/2/L25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Table 4 in Levesque, Emily M.; Massey, Philip; Olsen, K. A. G.; Plez, Bertrand; Josselin, Eric; Maeder, Andre; Meynet, Georges (2005). "The Effective Temperature Scale of Galactic Red Supergiants: Cool, but Not as Cool as We Thought". The Astrophysical Journal. 628 (2): 973. arXiv:astro-ph/0504337. Bibcode:2005ApJ...628..973L. doi:10.1086/430901.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at Levesque, Emily M.; Massey, Philip; Olsen, K.A.G.; Plez, Bertrand; Meynet, Georges; Maeder, Andre (2006). "The Effective Temperatures and Physical Properties of Magellanic Cloud Red Supergiants: The Effects of Metallicity". The Astrophysical Journal. 645 (2): 1102. arXiv:astro-ph/0603596. Bibcode:2006ApJ...645.1102L. doi:10.1086/504417.

- ^ Alcolea, J; Bujarrabal, V; Planesas, P; Teyssier, D; Cernicharo, J; De Beck, E; Decin, L; Dominik, C; Justtanont, K; De Koter, A; Marston, A. P; Melnick, G; Menten, K. M; Neufeld, D. A; Olofsson, H; Schmidt, M; Schöier, F. L; Szczerba, R; Waters, L. B. F. M (2013). "HIFISTARSHerschel/HIFI observations of VY Canis Majoris". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 559: A93. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321683.

- ^ a b Wittkowski, M.; Hauschildt, P. H.; Arroyo-Torres, B.; Marcaide, J. M. (2012). "Fundamental properties and atmospheric structure of the red supergiant VY Canis Majoris based on VLTI/AMBER spectro-interferometry". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 540: L12. arXiv:1203.5194. Bibcode:2012A&A...540L..12W. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219126.

- ^ a b Choi, Yoon Kyung; et al. (2008). "Distance to VY CMa with VERA". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 60 (5). Publications Astronomical Society of Japan: 1007. arXiv:0808.0641. Bibcode:2008PASJ...60.1007C. doi:10.1093/pasj/60.5.1007.

- ^ Humphreys, Roberta M. (2006). "VY Canis Majoris: The Astrophysical Basis of Its Luminosity": arXiv:astro–ph/0610433. arXiv:astro-ph/0610433. Bibcode:2006astro.ph.10433H.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Massey, Philip; Levesque, Emily M.; Plez, Bertrand (1 August 2006). "Bringing VY Canis Majoris down to size: an improved determination of its effective temperature". The Astrophysical Journal. 646 (2): 1203–1208. arXiv:astro-ph/0604253. Bibcode:2006ApJ...646.1203M. doi:10.1086/505025.

- ^ Bauer, W. H.; Gull, T. R.; Bennett, P. D. (2008). "Spatial Extension in the Ultraviolet Spectrum of Vv Cephei". The Astronomical Journal. 136 (3): 1312. Bibcode:2008AJ....136.1312H. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/136/3/1312.

- ^ a b Wright, K. O. (1977). "The system of VV Cephei derived from an analysis of the H-alpha line". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 71: 152. Bibcode:1977JRASC..71..152W.

- ^ Ridpath & Tirion 2001, pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b c Arroyo-Torres, B; Wittkowski, M; Marcaide, J. M; Hauschildt, P. H (June 2013). "The atmospheric structure and fundamental parameters of the red supergiants AH Scorpii, UY Scuti, and KW Sagittarii". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 554 (A76): A76. arXiv:1305.6179. Bibcode:2013A&A...554A..76A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220920.

- ^ a b Zhang, B.; Reid, M. J.; Menten, K. M.; Zheng, X. W.; Brunthaler, A. (2012). "The distance and size of the red hypergiant NML Cygni from VLBA and VLA astrometry". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 544: A42. arXiv:1207.1850. Bibcode:2012A&A...544A..42Z. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219587.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i De Beck, E.; Decin, L.; De Koter, A.; Justtanont, K.; Verhoelst, T.; Kemper, F.; Menten, K. M. (2010). "Probing the mass-loss history of AGB and red supergiant stars from CO rotational line profiles. II. CO line survey of evolved stars: Derivation of mass-loss rate formulae". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 523: A18. arXiv:1008.1083. Bibcode:2010A&A...523A..18D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200913771.

- ^ Levesque, Emily M; Massey, Philip; Plez, Bertrand; Olsen, Knut A. G (June 2009). "The Physical Properties of the Red Supergiant WOH G64: The Largest Star Known?". Astronomical Journal. 137 (6): 4744. arXiv:0903.2260. Bibcode:2009AJ....137.4744L. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/6/4744.

- ^ Ohnaka, K.; Driebe, T.; Hofmann, K. H.; Weigelt, G.; Wittkowski, M. (2009). "Resolving the dusty torus and the mystery surrounding LMC red supergiant WOH G64". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 4: 454. Bibcode:2009IAUS..256..454O. doi:10.1017/S1743921308028858.

- ^ Humphreys, R. M. (1978). "Studies of luminous stars in nearby galaxies. I. Supergiants and O stars in the Milky Way". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 38: 309. Bibcode:1978ApJS...38..309H. doi:10.1086/190559.

- ^ Davies, Ben; Kudritzki, Rolf-Peter; Figer, Donald F. (2010). "The potential of red supergiants as extragalactic abundance probes at low spectral resolution". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 407 (2): 1203. arXiv:1005.1008. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.407.1203D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.16965.x.

- ^ Wright, Nicholas J; Wesson, Roger; Drew, Janet E; Barentsen, Geert; Barlow, Michael J; Walsh, Jeremy R; Zijlstra, Albert; Drake, Jeremy J; Eislöffel, Jochen; Farnhill, Hywel J (2014). "The ionized nebula surrounding the red supergiant W26 in Westerlund 1". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 437: L1. arXiv:1309.4086. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.437L...1W. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slt127.

- ^ a b c Fok, Thomas K. T; Nakashima, Jun-ichi; Yung, Bosco H. K; Hsia, Chih-Hao; Deguchi, Shuji (2012). "Maser Observations of Westerlund 1 and Comprehensive Considerations on

Maser Properties of Red Supergiants Associated with Massive Clusters". The Astrophysical Journal. 760: 65. arXiv:1209.6427. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/760/1/65.

{{cite journal}}: line feed character in|title=at position 71 (help) - ^ a b c Mauron, N.; Josselin, E. (2011). "The mass-loss rates of red supergiants and the de Jager prescription". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 526: A156. arXiv:1010.5369. Bibcode:2011A&A...526A.156M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201013993.

- ^ Lockwood, G.W.; Wing, R. F. (1982). "The light and spectrum variations of VX Sagittarii, an extremely cool supergiant". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 198 (2): 385–404. Bibcode:1982MNRAS.198..385L. doi:10.1093/mnras/198.2.385.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Davies, B.; Figer, D. F.; Law, C. J.; Kudritzki, R. P.; Najarro, F.; Herrero, A.; MacKenty, J. W. (2008). "The Cool Supergiant Population of the Massive Young Star Cluster RSGC1". The Astrophysical Journal. 676 (2): 1016–1028. arXiv:0711.4757. Bibcode:2008ApJ...676.1016D. doi:10.1086/527350.

- ^ Chesneau, O.; Meilland, A.; Chapellier, E.; Millour, F.; Van Genderen, A. M.; Nazé, Y.; Smith, N.; Spang, A.; Smoker, J. V.; Dessart, L.; Kanaan, S.; Bendjoya, Ph.; Feast, M. W.; Groh, J. H.; Lobel, A.; Nardetto, N.; Otero, S.; Oudmaijer, R. D.; Tekola, A. G.; Whitelock, P. A.; Arcos, C.; Curé, M.; Vanzi, L. (2014). "The yellow hypergiant HR 5171 A: Resolving a massive interacting binary in the common envelope phase". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 563: A71. arXiv:1401.2628v2. Bibcode:2014A&A...563A..71C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322421.

- ^ Wittkowski, M; Abellan, F. J; Arroyo-Torres, B; Chiavassa, A; Guirado, J. C; Marcaide, J. M; Alberdi, A; De Wit, W. J; Hofmann, K.-H; Meilland, A; Millour, F; Mohamed, S; Sanchez-Bermudez, J (28 September 2017). "Multi-epoch VLTI-PIONIER imaging of the supergiant V766 Cen: Image of the close companion in front of the primary". 1709: arXiv:1709.09430. arXiv:1709.09430. Bibcode:2017arXiv170909430W.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Wittkowski, M.; Arroyo-Torres, B.; Marcaide, J. M.; Abellan, F. J.; Chiavassa, A.; Guirado, J. C. (2017). "VLTI/AMBER spectro-interferometry of the late-type supergiants V766 Cen (=HR 5171 A), σ Oph, BM Sco, and HD 206859". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 597: A9. arXiv:1610.01927. Bibcode:2017A&A...597A...9W. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629349.

- ^ Kusuno, K.; Asaki, Y.; Imai, H.; Oyama, T. (2013). "Distance and Proper Motion Measurement of the Red Supergiant, Pz Cas, in Very Long Baseline Interferometry H2O Maser Astrometry". The Astrophysical Journal. 774 (2): 107. arXiv:1308.3580. Bibcode:2013ApJ...774..107K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/774/2/107.

- ^ a b Josselin, E.; Plez, B. (2007). "Atmospheric dynamics and the mass loss process in red supergiant stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 469 (2): 671–680. arXiv:0705.0266. Bibcode:2007A&A...469..671J. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066353.

- ^ a b https://groups.google.com/forum/?hl=en#!topic/uk.sci.astronomy/9nKaTsFHw6w

- ^ Tsuji, Takashi (2000). "Water in Emission in the Infrared Space Observatory Spectrum of the Early M Supergiant Star μ Cephei". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 540 (2): 99–102. arXiv:astro-ph/0008058. Bibcode:2000ApJ...540L..99T. doi:10.1086/312879.

- ^ Thompson, R. R.; Creech-Eakman, M. J. (2003). "Interferometric observations of the supergiant S Persei: Evidence for axial symmetry and the warm molecular layer". American Astronomical Society Meeting 203. 203: 49.07. Bibcode:2003AAS...203.4907T.

- ^ Gvaramadze, V. V.; Menten, K. M.; Kniazev, A. Y.; Langer, N.; MacKey, J.; Kraus, A.; Meyer, D. M.-A.; Kamiński, T. (2014). "IRC -10414: A bow-shock-producing red supergiant star". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 437: 843. arXiv:1310.2245. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.437..843G. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1943.

- ^ Van Loon, J. Th.; Cioni, M.-R. L.; Zijlstra, A. A.; Loup, C. (2005). "An empirical formula for the mass-loss rates of dust-enshrouded red supergiants and oxygen-rich Asymptotic Giant Branch stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 438: 273. arXiv:astro-ph/0504379. Bibcode:2005A&A...438..273V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20042555.

- ^ De Jager, C; Nieuwenhuijzen, H; Van Der Hucht, K. A (1988). "Mass loss rates in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series (ISSN 0365-0138). 72: 259. Bibcode:1988A&AS...72..259D.

- ^ Turner, David G.; Rohanizadegan, Mina; Berdnikov, Leonid N.; Pastukhova, Elena N. (2006). "The Long-Term Behavior of the Semiregular M Supergiant Variable BC Cygni". The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 118 (849): 1533. Bibcode:2006PASP..118.1533T. doi:10.1086/508905.

- ^ Massey, Philip; Levesque, Emily M.; Olsen, K. A. G.; Plez, Bertrand; Skiff, B. A. (2007). "HV 11423: The Coolest Supergiant in the SMC". The Astrophysical Journal. 660: 301. arXiv:astro-ph/0701769. Bibcode:2007ApJ...660..301M. doi:10.1086/513182.

- ^ Paumard, T; Pfuhl, O; Martins, F; Kervella, P; Ott, T; Pott, J.-U; Le Bouquin, J. B; Breitfelder, J; Gillessen, S; Perrin, G; Burtscher, L; Haubois, X; Brandner, W (2014). "GCIRS 7, a pulsating M1 supergiant at the Galactic centre . Physical properties and age". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 568: A85. arXiv:1406.5320. Bibcode:2014A&A...568A..85P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201423991.

- ^ Neilson, H. R.; Lester, J. B.; Haubois, X. (December 2011). "Weighing Betelgeuse: Measuring the Mass of α Orionis from Stellar Limb-darkening". Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 9th Pacific Rim Conference on Stellar Astrophysics. Proceedings of a conference held at Lijiang, China in 14–20 April 2011. ASP Conference Series, Vol. 451: 117. arXiv:1109.4562. Bibcode:2010ASPC..425..103L.

- ^ Dolan, Michelle M.; Mathews, Grant J.; Lam, Doan Duc; Lan, Nguyen Quynh; Herczeg, Gregory J.; Dearborn, David S. P. (2016). "Evolutionary Tracks for Betelgeuse". The Astrophysical Journal. 819: 7. arXiv:1406.3143v2. Bibcode:2016ApJ...819....7D. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/819/1/7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ https://books.google.fr/books?id=PVJEAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA307&lpg=PA307&source=bl&ots=E8NkQljjHI&sig=IM29LXM2IgR_O8z2kr7J18RljV0&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiouMPaxP3XAhUCyqQKHQm7DL4Q6AEIWzAJ#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ^ Ramstedt, S.; Schöier, F. L.; Olofsson, H. (2009). "Circumstellar molecular line emission from S-type AGB stars: mass-loss rates and SiO abundances". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 499 (2): 515–527. arXiv:0903.1672. Bibcode:2009A&A...499..515R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200911730.

- ^ Ramstedt, S.; Schöier, F. L.; Olofsson, H.; Lundgren, A. A. (2006). "Mass-loss properties of S-stars on the AGB". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 454 (2): L103. arXiv:astro-ph/0605664. Bibcode:2006A&A...454L.103R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20065285.

- ^ Levesque, Emily M.; Massey, P.; Zytkow, A. N.; Morrell, N. (1 September 2014). "Discovery of a Thorne-̇Żytkow object candidate in the Small Magellanic Cloud". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 443: L94. arXiv:1406.0001. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.443L..94L. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slu080.

- ^ Arroyo-Torres, B.; Wittkowski, M.; Chiavassa, A.; Scholz, M.; Freytag, B.; Marcaide, J. M.; Hauschildt, P. H.; Wood, P. R.; Abellan, F. J. (2015). "What causes the large extensions of red supergiant atmospheres?. Comparisons of interferometric observations with 1D hydrostatic, 3D convection, and 1D pulsating model atmospheres". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 575: A50. arXiv:1501.01560. Bibcode:2015A&A...575A..50A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201425212.

- ^ Baron, F.; Monnier, J. D.; Kiss, L. L.; Neilson, H. R.; Zhao, M.; Anderson, M.; Aarnio, A.; Pedretti, E.; Thureau, N.; Ten Brummelaar, T. A.; Ridgway, S. T.; McAlister, H. A.; Sturmann, J.; Sturmann, L.; Turner, N. (2014). "CHARA/MIRC Observations of Two M Supergiants in Perseus OB1: Temperature, Bayesian Modeling, and Compressed Sensing Imaging". The Astrophysical Journal. 785: 46. arXiv:1405.4032. Bibcode:2014ApJ...785...46B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/785/1/46.

- ^ Stickland, D. J. (1985). "IRAS observations of the cool galactic hypergiants". The Observatory. 105: 229. Bibcode:1985Obs...105..229S.

- ^ a b Bergeat, J.; Chevallier, L. (2005). "The mass loss of C-rich giants". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 429: 235. arXiv:astro-ph/0601366. Bibcode:2005A&A...429..235B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041280. pp. 235-246.

- ^ "Carina Constellation: Facts, Myth, Star Map, Major Stars, Deep Sky Objects | Constellation Guide". www.constellation-guide.com. Retrieved 2017-10-28.

- ^ Achmad, L. (1992). "A photometric study of the G0-4 Ia(+) hypergiant HD 96918 (V382 Carinae)". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 259: 600–606. Bibcode:1992A&A...259..600A.

- ^ Fok, Thomas K. T.; Nakashima, Jun-Ichi; Yung, Bosco H. K.; Hsia, Chih-Hao; Deguchi, Shuji (2012). "Maser Observations of Westerlund 1 and Comprehensive Considerations on Maser Properties of Red Supergiants Associated with Massive Clusters". The Astrophysical Journal. 760: 65. arXiv:1209.6427. Bibcode:2012ApJ...760...65F. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/760/1/65.

- ^ Wasatonic, Richard P.; Guinan, Edward F.; Durbin, Allyn J. (2015). "V-Band, Near-IR, and TiO Photometry of the Semi-Regular Red Supergiant TV Geminorum: Long-Term Quasi-Periodic Changes in Temperature, Radius, and Luminosity". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 127 (956): 1010. Bibcode:2015PASP..127.1010W. doi:10.1086/683261.

- ^ Hawkins, G. W; Skinner, C. J; Meixner, M. M; Jernigan, J. G; Arens, J. F; Keto, E; Graham, J. R (1995). "Discovery of an Extended Nebula around AFGL 2343 (HD 179821) at 10 Microns". Astrophysical Journal. 452: 314. Bibcode:1995ApJ...452..314H. doi:10.1086/176303.

- ^ a b Ohnaka, K; Hofmann, K.-H; Schertl, D; Weigelt, G; Baffa, C; Chelli, A; Petrov, R; Robbe-Dubois, S (2013). "High spectral resolution imaging of the dynamical atmosphere of the red supergiant Antares in the CO first overtone lines with VLTI/AMBER". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 555: A24. arXiv:1304.4800. Bibcode:2013A&A...555A..24O. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321063.

- ^ Pugh, T.; Gray, D. F. (2013-02-01). "On the Six-year Period in the Radial Velocity of Antares A". The Astronomical Journal. 145 (2): 38. Bibcode:2013AJ....145...38P. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/145/2/38. ISSN 0004-6256.

- ^ Baade, R.; Reimers, D. (2007-10-01). "Multi-component absorption lines in the HST spectra of alpha Scorpii B". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474: 229–237. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..229B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20077308. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ A. Richichi (April 1990). "A new accurate determination of the angular diameter of Antares". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 230 (2): 355–362. Bibcode:1990A&A...230..355R.

- ^ Perryman, M. A. C; Lindegren, L; Kovalevsky, J; Hoeg, E; Bastian, U; Bernacca, P. L; Crézé, M; Donati, F; Grenon, M; Grewing, M; Van Leeuwen, F; Van Der Marel, H; Mignard, F; Murray, C. A; Le Poole, R. S; Schrijver, H; Turon, C; Arenou, F; Froeschlé, M; Petersen, C. S (July 1997). "The HIPPARCOS Catalogue". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 323: L49–L52. Bibcode:1997A&A...323L..49P.

- ^ Montargès, M; Norris, R; Chiavassa, A; Tessore, B; Lèbre, A; Baron, F (2018). "The convective photosphere of the red supergiant CE Tau. I. VLTI/PIONIER H-band interferometric imaging". arXiv:1802.06086 [astro-ph.SR].

- ^ http://www.newforestobservatory.com/2012/07/02/the-second-reddest-star-in-the-sky-119-tauri-ce-tauri/

- ^ Hofmann, K.-H.; Eberhardt, M.; Driebe, T.; Schertl, D.; Scholz, M.; Schoeller, M.; Weigelt, G.; Wittkowski, M.; Woodruff, H. C. (2005). "Interferometric observations of the Mira star o Ceti with the VLTI/VINCI instrument in the near-infrared". Proceedings of the 13th Cambridge Workshop on Cool Stars. 560: 651. Bibcode:2005ESASP.560..651H.

- ^ Kaler, James B., "Hind's Crimson Star", Stars, University of Illinois, retrieved 2018-03-19

- ^ Gorlova, N.; Lobel, A.; Burgasser, A. J.; Rieke, G. H.; Ilyin, I.; Stauffer, J. R. (2006). "On the CO Near‐Infrared Band and the Line‐splitting Phenomenon in the Yellow Hypergiant ρ Cassiopeiae". The Astrophysical Journal. 651 (2): 1130–1150. arXiv:astro-ph/0607158. Bibcode:2006ApJ...651.1130G. doi:10.1086/507590.

- ^ Woodruff, H. C.; Eberhardt, M.; Driebe, T.; Hofmann, K.-H.; et al. (2004). "Interferometric observations of the Mira star o Ceti with the VLTI/VINCI instrument in the near-infrared". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 421 (2): 703–714. arXiv:astro-ph/0404248. Bibcode:2004A&A...421..703W. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20035826.

- ^ Nieuwenhuijzen, H.; De Jager, C.; Kolka, I.; Israelian, G.; Lobel, A.; Zsoldos, E.; Maeder, A.; Meynet, G. (2012). "The hypergiant HR 8752 evolving through the yellow evolutionary void". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 546: A105. Bibcode:2012A&A...546A.105N. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117166.

- ^ "Structure and physical properties of the rapidly evolving dusty envelope of IRC +10216 reconstructed by detailed two-dimensional radiative transfer modeling". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 392 (3): 921. 2001. arXiv:astro-ph/0206410. Bibcode:2002A&A...392..921M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020954.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Weigelt, G.; et al. (May 1998), "76mas speckle-masking interferometry of IRC+10216 with the SAO 6m telescope: Evidence for a clumpy shell structure", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 333: L51–L54, arXiv:astro-ph/9805022, Bibcode:1998A&A...333L..51W

- ^ Tylenda, R.; Kamiński, T.; Schmidt, M.; Kurtev, R.; Tomov, T. (2011). "High-resolution optical spectroscopy of V838 Monocerotis in 2009". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 532: A138. arXiv:1103.1763. Bibcode:2011A&A...532A.138T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116858.

- ^ Lane, B. F.; Retter, A.; Thompson, R. R.; Eisner, J. A. (April 2005). "Interferometric Observations of V838 Monocerotis". The Astrophysical Journal. 622 (2). The American Astronomical Society: L137–L140. arXiv:astro-ph/0502293. Bibcode:2005ApJ...622L.137L. doi:10.1086/429619.

- ^ Lamers, H. J. G. L. M. (February 6–10, 1995). "Observations and Interpretation of Luminous Blue Variables". Proceedings of IAU Colloquium 155, Astrophysical applications of stellar pulsation. Astrophysical applications of stellar pulsation. Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series. Vol. 83. Cape Town, South Africa: Astronomical Society of the Pacific. pp. 176–191. Bibcode:1995ASPC...83..176L.

- ^ Bedding, T. R.; et al. (April 1997), "The angular diameter of R Doradus: a nearby Mira-like star", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 286 (4): 957–962, arXiv:astro-ph/9701021, Bibcode:1997MNRAS.286..957B, doi:10.1093/mnras/286.4.957

- ^ Dinh-V.-Trung; Muller, Sébastien; Lim, Jeremy; Kwok, Sun; Muthu, C. (2009). "Probing the Mass-Loss History of the Yellow Hypergiant IRC+10420". The Astrophysical Journal. 697: 409. arXiv:0903.3714v1. Bibcode:2009ApJ...697..409D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/697/1/409.

- ^ Najarro, F.; Figer, D. F.; Hillier, D. J.; Geballe, T. R.; Kudritzki, R. P. (2009). "Metallicity in the Galactic Center: The Quintuplet Cluster". The Astrophysical Journal. 691 (2): 1816. arXiv:0809.3185. Bibcode:2009ApJ...691.1816N. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/691/2/1816.

- ^ Luttermoser, Donald G.; Brown, Alexander (1992). "A VLA 3.6 centimeter survey of N-type carbon stars". Astrophysical Journal. 384: 634. Bibcode:1992ApJ...384..634L. doi:10.1086/170905.

- ^ a b Moravveji, Ehsan; Guinan, Edward F.; Khosroshahi, Habib; Wasatonic, Rick (2013). "The Age and Mass of the α Herculis Triple-star System from a MESA Grid of Rotating Stars with 1.3 <= M/M ⊙ <= 8.0". The Astronomical Journal. 146 (6): 148. arXiv:1308.1632. Bibcode:2013AJ....146..148M. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/146/6/148.

- ^ Rybicki, K. R.; Denis, C. (2001). "On the Final Destiny of the Earth and the Solar System". Icarus. 151 (1): 130–137. Bibcode:2001Icar..151..130R. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6591.

- ^ Kashi, A.; Soker, N. (2010). "Periastron Passage Triggering of the 19th Century Eruptions of Eta Carinae". The Astrophysical Journal. 723: 602. arXiv:0912.1439. Bibcode:2010ApJ...723..602K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/723/1/602.

- ^ Gull, T. R.; Damineli, A. (2010). "JD13 – Eta Carinae in the Context of the Most Massive Stars". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 5: 373. arXiv:0910.3158. Bibcode:2010HiA....15..373G. doi:10.1017/S1743921310009890.

- ^ "The HST Treasury Program on Eta Carinae". Etacar.umn.edu. 2003-09-01. Retrieved 2017-11-05.

- ^ Schiller, F.; Przybilla, N. (2008). "Quantitative spectroscopy of Deneb". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 479 (3): 849–858. arXiv:0712.0040. Bibcode:2008A&A...479..849S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078590.

- ^ http://www.solstation.com/x-objects/1806-20.htm

- ^ Kloppenborg, B.K.; Stencel, R.E.; Monnier, J.D.; Schaefer, G.H.; Baron, F.; Tycner, C.; Zavala, R. T.; Hutter, D.; Zhao, M.; Che, X.; Ten Brummelaar, T. A.; Farrington, C.D.; Parks, R.; McAlister, H. A.; Sturmann, J.; Sturmann, L.; Sallave-Goldfinger, P.J.; Turner, N.; Pedretti, E.; Thureau, N. (2015). "Interferometry of ɛ Aurigae: Characterization of the Asymmetric Eclipsing Disk". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 220: 14. arXiv:1508.01909. Bibcode:2015ApJS..220...14K. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/220/1/14.

- ^ Ask Andy: The Biggest Star

- ^ Barniske, A.; Oskinova, L. M.; Hamann, W. -R. (2008). "Two extremely luminous WN stars in the Galactic center with circumstellar emission from dust and gas". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 486 (3): 971. arXiv:0807.2476. Bibcode:2008A&A...486..971B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809568.

- ^ Moravveji, Ehsan; Guinan, Edward F.; Shultz, Matt; Williamson, Michael H.; Moya, Andres (March 2012). "Asteroseismology of the nearby SN-II Progenitor: Rigel. Part I. The MOST High-precision Photometry and Radial Velocity Monitoring". The Astrophysical Journal. 747 (1): 108–115. arXiv:1201.0843. Bibcode:2012ApJ...747..108M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/747/2/108.

- ^ =Chesneau, O.; Kaufer, A.; Stahl, O.; Colvinter, C.; Spang, A.; Dessart, L.; Prinja, R.; Chini, R. (2014). "The variable stellar wind of Rigel probed at high spatial and spectral resolution". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 566: 18. arXiv:1405.0907. Bibcode:2014A&A...566A.125C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322894. A125.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Cruzalebes, P.; Jorissen, A.; Rabbia, Y.; Sacuto, S.; Chiavassa, A.; Pasquato, E.; Plez, B.; Eriksson, K.; Spang, A.; Chesneau, O. (2013). "Fundamental parameters of 16 late-type stars derived from their angular diameter measured with VLTI/AMBER". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 434 (1): 437–450. arXiv:1306.3288. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.434..437C. doi:10.1093/mnras/stt1037.

- ^ Piau, L; Kervella, P; Dib, S; Hauschildt, P (February 2011). "Surface convection and red-giant radius measurements". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 526: A100. arXiv:1010.3649. Bibcode:2011A&A...526A.100P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014442.

- ^ Fadeyev, Y. A. (2015). "Evolutionary status of Polaris". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 449: 1011. arXiv:1502.06463. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.449.1011F. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv412.

- ^ Crowther, P. A.; Schnurr, O.; Hirschi, R.; Yusof, N.; Parker, R. J.; Goodwin, S. P.; Kassim, H. A. (2010). "The R136 star cluster hosts several stars whose individual masses greatly exceed the accepted 150 M⊙ stellar mass limit". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 408 (2): 731. arXiv:1007.3284. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.408..731C. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17167.x.

- ^ I. Ramírez; C. Allende Prieto (December 2011). "Fundamental Parameters and Chemical Composition of Arcturus". The Astrophysical Journal. 743 (2): 135. arXiv:1109.4425. Bibcode:2011ApJ...743..135R. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/743/2/135.

- ^ Ziółkowski, J. (2005), "Evolutionary constraints on the masses of the components of HDE 226868/Cyg X-1 binary system", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 358 (3): 851–859, arXiv:astro-ph/0501102, Bibcode:2005MNRAS.358..851Z, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.08796.x Note: for radius and luminosity, see Table 1 with d=2 kpc.

- ^ Hack, M.; Engin, S.; Yilmaz, N.; Sedmak, G.; Rusconi, L.; Boehm, C. (1992). "Spectroscopic study of the atmospheric eclipsing binary VV Cephei". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series (ISSN0365-0138). 95: 589. Bibcode:1992A&AS...95..589H.