Micah (prophet)

Micah the Prophet | |

|---|---|

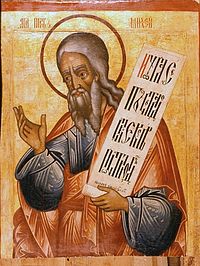

Russian Orthodox icon of the Prophet Micah, 18th century (Iconostasis of Transfiguration Church, Kizhi Monastery, Karelia, Russia). | |

| Prophet | |

| Born | Moresheth |

| Venerated in | Judaism, Islam, Christianity, (Armenian Apostolic Church, Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church) |

| Feast | July 31 Roman Catholic January 5 and August 14 Eastern Orthodox |

Micah (Hebrew: מִיכָה הַמֹּרַשְׁתִּי mīkhā hammōrashtī “Micah the Morashtite”) was a prophet in Judaism who prophesied from approximately 737 to 696 BC in Judah and is the author of the Book of Micah. He is considered one of the twelve minor prophets of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) and was a contemporary of the prophets Isaiah, Amos and Hosea. Micah was from Moresheth-Gath, in southwest Judah. He prophesied during the reigns of kings Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah of Judah. Micah’s messages were directed chiefly toward Jerusalem. He prophesied the future destruction of Jerusalem and Samaria, the destruction and then future restoration of the Judean state, and he rebuked the people of Judah for dishonesty and idolatry. His prophecy that the Messiah would be born in the town of Bethlehem is cited in the Gospel of Matthew. Information about the end of his life is not known.

Background

Micah was active in Judah from before the fall of Samaria in 722 BC and experienced the devastation brought by Sennacherib’s invasion of Judah in 701 BC. He prophesied from approximately 737 to 696 BC. Micah was from Moresheth, also called Moresheth-Gath, a small town in southwest Judah. Micah lived in a rural area, but often rebuked the corruption of city life in Israel and Judah.[1]

Micah prophesied during the reigns of kings Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah of Judah. Jotham, the son of Uzziah, was king of Judah from 742 to 735 BC. Jotham was succeeded by his son Ahaz, who reigned over Judah from 735 to 715 BC. Then Ahaz’s son Hezekiah ruled from 715 to 696 BC.[2] Micah was a contemporary of the prophets Isaiah, Amos, and Hosea. Jeremiah, who prophesied about thirty years after Micah, recognized Micah as a prophet from Moresheth who prophesied during the reign of Hezekiah.[3]

Message

His messages were directed mainly towards Jerusalem, and were a mixture of denunciations and prophecies. In his early prophecies, he predicted the destruction of both Samaria and Jerusalem for their respective sins. The people of Samaria were rebuked for worshipping idols which were bought with the income earned by prostitutes.[4] Micah was the first prophet to predict the downfall of Jerusalem. According to him, the city was doomed because its beautification was financed by dishonest business practices, which impoverished the city’s citizens.[5] He also called to account the prophets of his day, whom he accused of accepting money for their oracles.[6]

Micah also anticipated the destruction of the Judean state and promised its restoration more glorious than before.[7] He prophesied an era of universal peace over which the Governor will rule from Jerusalem.[8] Micah also declared that when the glory of Zion and Jacob is restored that the LORD will force the Gentiles to abandon idolatry.[9]

Micah also rebuked Israel because of dishonesty in the marketplace and corruption in government. He warned the people, on behalf of God, of pending destruction if ways and hearts were not changed. He told them what the LORD requires of them:

He hath shewed thee, O man, what is good; and what doth the LORD require of thee, but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?

Israel’s response to Micah’s charges and threats consisted of three parts: an admission of guilt,[10] a warning of adversaries that Israel will rely on the LORD for deliverance and forgiveness,[11] and a prayer for forgiveness and deliverance.[12]

Another prophecy given by Micah details the future destruction of Jerusalem and the plowing of Zion (a part of Jerusalem). This passage (Micah 3:11–12), is stated again in Jeremiah 26:18, Micah’s only prophecy repeated in the Old Testament. Since then Jerusalem has been destroyed three times, the first one being the fulfillment of Micah’s prophecy. The Babylonians destroyed Jerusalem in 586 BC, about 150 years after Micah gave this prophecy.[13][14]

Elsewhere in the Bible

Micah 5:2 is interpreted as a prophecy that Bethlehem, a small village just south of Jerusalem, would be the birthplace of the Messiah.

But thou, Bethlehem Ephratah, though thou be little among the thousands of Judah, yet out of thee shall he come forth unto me that is to be ruler in Israel; whose goings forth have been from of old, from everlasting.

This passage is recalled in Matthew 2:6, and the fulfillment of this prophecy in the birth of Jesus is further described in Matthew 2:1–6.

And thou Bethlehem, in the land of Juda, art not the least among the princes of Juda: for out of thee shall come a Governor, that shall rule my people Israel.

In Matthew 10:35–36 Jesus adapts Micah 7:6 to his own situation;

For I am come to set a man at variance against his father, and the daughter against her mother, and the daughter in law against her mother in law. And a man's foes shall be they of his own household.

Micah was referring to the division in Judah and Samaria, the distrust that had arisen between all citizens, even within families.[14] Jesus was using the same words to describe something different. Jesus said that he did not come to bring peace, but to divide households. Men are commanded to love Jesus Christ more than their own family members, and Jesus indicated that this priority would lead to persecution from others and separation within families.[15]

In Micah 7:20, Micah reminded Judah of God’s covenant to be merciful to Jacob and show love to Abraham and his descendants. This is repeated in Luke 1:72–73 in the prophecy Zechariah at the circumcision and naming of John the Baptist. This prophecy concerned the kingdom and salvation through the Messiah. It is a step in the fulfillment of the blessing of the descendants of Abraham.[15] When Micah restated this covenant promise, he was comforting Judah with the promise of God’s faithfulness and love.[16]

Micah's prophecy to King Hezekiah is mentioned in Jeremiah 26:17-19:

17 Then certain of the elders of the land rose up and spoke to all the assembly of the people, saying: 18 “Micah of Moresheth prophesied in the days of Hezekiah king of Judah, and spoke to all the people of Judah, saying, ‘Thus says the Lord of hosts:

“Zion shall be plowed like a field, Jerusalem shall become heaps of ruins, And the mountain of the temple[a] Like the bare hills of the forest.”’[b] 19 Did Hezekiah king of Judah and all Judah ever put him to death? Did he not fear the Lord and seek the Lord’s favor? And the Lord relented concerning the doom which He had pronounced against them. But we are doing great evil against ourselves.”

Islam

Although the Quran only mentions around twenty-five prophets by name, and alludes to a few others, it has been a cardinal doctrine of Islam that many more prophets were sent by God who are not mentioned in the scripture.[17] Thus, Muslims have traditionally had no problem accepting those other Hebrew prophets not mentioned in the Quran or hadith as legitimate prophets of God, especially as the Quran itself states: "Surely We sent down the Torah (to Moses), wherein is guidance and light; thereby the Prophets (who followed him), who had surrendered themselves, gave judgment for those who were Jewish, as did the masters and the rabbis, following such portion of God's Book as they were given to keep and were witnesses to,"[18] with this passage having often been interpreted by Muslims to include within the phrase "prophets" an allusion to all the prophetic figures of the Jewish scriptural portion of the nevi'im, that is to say all the prophets of Israel after Moses and Aaron. Thus, Islamic authors have often alluded to Micah as a prophet in their works.[19]

Liturgical commemoration

Micah is commemorated with the other twelve minor prophets in the Calendar of Saints (Armenian Apostolic Church) on July 31. In the Eastern Orthodox Church he is commemorated twice in the year. The first feast day is January 5 (for those churches which follow the traditional Julian Calendar, January 5 currently falls on January 18 of the modern Gregorian Calendar). However, since January 5 is also the eve of the Great Feast of Theophany (in the west, Epiphany) and a strict fast day (near total abstinence from food and non-religious activities), his major celebration is on August 14 (the forefeast of the Great Feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God)[20].

References

- ^ Powell, Mark Allan (2011). Book of Micah. HarperCollins. p. PT995. ISBN 0062078593. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|encyclopedia=ignored (help) - ^ "Micah, Book of", New Bible Dictionary, Second Edition, Tyndale Press, 1987 pp. 772–773.

- ^ Jeremiah 26:18; Jeremiah 26. Henry, Matthew. Matthew Henry’s Concise Commentary on the Whole Bible. Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2000. Page 589.

- ^ Micah 1:7; "Micah, Book of", The Illustrated Dictionary and Concordance of the Bible, The Jerusalem Publishing House, Ltd., 1986. p. 688–689.

- ^ Micah 2:1–2; "Micah, Book of", The Anchor Bible Dictionary. Volume 4. Bantan Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, 1992. p. 807–810

- ^ Micah 3:5–6; "Micah", New Bible Dictionary, Second Edition, Tyndale Press, 1987 p. 772.

- ^ Micah 5:6–8; Micah, a translation with notes from J. Sharpe. Micah (the prophet), ed. John Sharpe. 1876. Oxford University Press. pp 33–34

- ^ Micah 5:1–2; The History of the Hebrew Nation and its Literature with an appendix on the Hebrew chronology. Sharpe, Samuel. Harvard University Press, 1908. p. 27

- ^ Micah 5:10–15; "Micah, Book of", The Illustrated Dictionary and Concordance of the Bible, The Jerusalem Publishing House, Ltd., 1986. p. 688–689.

- ^ Micah 7:1–6; Micah: A Commentary. Mays, James Luther. Old Testament Library. Westminster John Knox Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0-664-20817-2. p. 131–133.

- ^ Micah 7:7–13; Micah, a translation with notes from J. Sharpe. Micah (the prophet), ed. John Sharpe. 1876. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Micah 7:14–20; "Micah, Book of", New Bible Dictionary, Second Edition, Tyndale Press, 1987 p. 772–773

- ^ The History of the Hebrew Nation and its Literature with an appendix on the Hebrew chronology. Sharpe, Samuel. Harvard University Press, 1908. p. 27

- ^ a b Micah: A Commentary. Mays, James Luther. Old Testament Library. Westminster John Knox Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0-664-20817-2. p. 131–133.

- ^ a b Matthew 10. Henry, Matthew. Matthew Henry’s Concise Commentary on the Whole Bible. Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2000. Page 381.

- ^ Micah 7. The Holy Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments…with commentary and notes by Adam Clarke. Clarke, Adam. Columbia University, 1833. p. 347.

- ^ Cf. Qur'an 16:36

- ^ Qur'an 5:44, cf. Arberry translation.

- ^ Camilla Adang, Muslim Writers on Judaism and the Hebrew Bible (Leiden: Brill, 1996), pp. 129, 144

- ^ "Prophet Micah in the Eastern Orthodox Church". Orthodox Church of America. Archived from the original on Oct 10, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Bibliography

- Delbert R. Hillers, Micah (Minneapolis, Fortress Press, 1984) (Nurse).

- Bruce K. Waltke, A Commentary on Micah (Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 2007).

- Mignon Jacobs, Conceptual Coherence of the Book of Micah (Sheffield, Sheffield Academic Press, 2009).

- Yair Hoffman Engel, "The Wandering Lament: Micah 1:10–16," in Mordechai Cogan and Dan`el Kahn (eds), Treasures on Camels' Humps: Historical and Literary Studies from the Ancient Near East Presented to Israel Eph`al (Jerusalem, Magnes Press, 2008),

External links

- Prophet Micah Orthodox icon and synaxarion for August 14

- Historical and Literary Overview