Middle Low German

This article is missing information about example texts in Middle Low German. (May 2017) |

| Middle Low German | |

|---|---|

| Sassisch | |

| Region | Northern Germany (roughly the Northern lowlands), Northeastern Netherlands, Northwestern/North-central (modern) Poland, modern Kaliningrad Oblast, sporadically in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Latvia, Estonia (confined to cities) |

| Era | 13th to 16th centuries; evolved into Modern Low German and was gradually superseded by High German |

Indo-European

| |

Early form | |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin (Fraktur) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | gml |

| Glottolog | midd1318 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ACB-ca[1] |

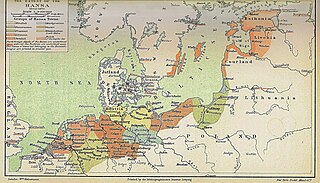

Northern Europe in 1400, showing the extent of the Hanseatic League | |

Middle Low German or Middle Saxon (autonym: Sassisch[2][3], i.e. 'Saxon', Standard High German: Mittelniederdeutsch) is a developmental stage of Low German. It developed from the Old Saxon language in the Middle Ages and has been documented in writing since about 1225/34 (Sachsenspiegel). During the Hanseatic period (from about 1300 to about 1600), Middle Low German was the leading written language in the north of Central Europe and served as a lingua franca in the northern half of Europe. It was used parallel to medieval Latin also for purposes of diplomacy and for deeds.[4]

Terminology

While Middle Low German (MLG) is a scholarly term developed in hindsight, speakers in their time referred to the language mainly as sassisch (Saxon) or de sassische sprâke (the Saxon language). This terminology was also still known in Luther's time in the adjacent Central German-speaking areas.[5] Its Latin equivalent saxonicus was also used as meaning 'Low German' (among other meanings).[6][7] Some languages whose first contacts with Germany were via Low German-speaking 'Saxons', took their name as meaning 'German' in general, e.g. Finnish saksa 'German'.

In contrast to Latin as the primary written language, speakers also referred to discourse in Saxon as speaking/writing to dǖde, i.e. 'clearly, intelligibly',[8][9] which contains the same root as dǖdesch 'German' (cf. High German: deutsch, both from PG *þiudiskaz 'popular, vernacular'). Compare also the modern colloquial term Platt(dütsch) (from platt 'plain, simple') denoting Low (or West Central) German dialects in contrast to the written standard.

Another medieval term is ôstersch, lit. 'East-ish', which was at first applied to the Hanseatic cities of the Baltic Sea (the 'East Sea'), their territory being called Ôsterlant ('East-land'), their inhabitants - Ôsterlinge ('Eastlings'). This appellation was later expanded to other German Hanseatic cities and it was a general name for Hanseatic merchants in the Netherlands, e.g. in their komptôr (office) in Bruges.[10][11]

In the 16th century, the term nedderlendisch, lit. 'Lowland-ish, Netherlandish', gained ground, contrasting Saxon with the German dialects in the uplands to the south. It became dominant in the High German dialects (as niderländisch, which could also refer to the modern Netherlands), while sassisch remained the most widespread term within MLG. The equivalent of 'Low German' (NHG niederdeutsch) seems to have been introduced later on by High German speakers and at first applied especially to Netherlanders.[12]

Middle Low German is a modern term used with varying degrees of inclusivity. It is distinguished from Middle High German, spoken to the south, which was later replaced by Early New High German. Though Middle Dutch is today usually excluded from MLG (although very closely related), it is sometimes, esp. in older literature, included in MLG, which then encompasses the dialect continuum of all high-medieval Continental Germanic dialects outside MHG, from Flanders in the West to the eastern Baltic.[13][14]

History

Sub-periods of Middle Low German are:[15][16]

- Early Middle Low German (Standard High German: Frühmittelniederdeutsch): 1200–1350, or 1200–1370

- Classical Middle Low German (klassisches Mittelniederdeutsch): 1350–1500, or 1370–1530

- Late Middle Low German (Spätmittelniederdeutsch): 1500–1600, or 1530–1650

Middle Low German was the lingua franca of the Hanseatic League, spoken all around the North Sea and the Baltic Sea. It used to be thought that the language of Lübeck was dominant enough to become a normative standard (the so-called Lübecker Norm) for an emergent spoken and written standard, but more recent work has established that there is no evidence for this and that Middle Low German was non-standardised.[17]

Middle Low German provided a large number of loanwords to languages spoken around the Baltic Sea as a result of the activities of Hanseatic traders. Its traces can be seen in the Scandinavian, Finnic, and Baltic languages, as well as Standard High German and English. It is considered the largest single source of loanwords in Danish, Estonian, Latvian, Norwegian and Swedish.

In the late Middle Ages, Middle Low German lost its prestige to Early New High German, which was first used by elites as a written and, later, a spoken language. Reasons for this loss of prestige include the decline of the Hanseatic League, followed by political heteronomy of Northern Germany and the cultural predominance of Middle and Southern Germany during the Protestant Reformation and Luther's translation of the Bible.

Phonology and Orthography

Consonants

Description based on Lasch (1914)[18] which continues to be the most authoritative comprehensive grammar of the language (though not necessarily in every detail) and is still occasionally reprinted.

| Labial | Alveolar | Post-alv. | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | [ŋ] | |||

| Stop | p b | t d | [c] | k [g] | ||

| Affricate | (t͡s) | |||||

| Fricative | f [v] | s [z] | (ʃ) | [ç] [ʝ] | [x] ɣ | h |

| Approximant | ʋ | r | j | |||

| Lateral | l |

- Square brackets indicate allophones.

- Round brackets indicate phonemes that do not have phoneme status in the whole language area or are marginal in the phonological system.

It has to be noted that it is not rare to find one and the same word in MLG affected by one of the following phonological processes in one text and not affected by it in another, due to the lack of a written standard, the dialectal variation as well as ongoing linguistic change during the Middle Low German (MLG) era.

General notes

- Final devoicing: Voiced obstruents in the syllable coda are devoiced, e.g. geven (to give) but gift (gift). This change took place early in MLG, but is not always represented in writing. Proclitic words like mid (with) might keep their voice before a vowel because they are perceived as one phonological unit with the following word. Also, as can already be seen in Old Saxon, lenited /b/ is devoiced to [f] before syllabic nasals or liquids, e.g. gaffel (fork) from PG *gabalō.

- Grammatischer Wechsel: Because of sound changes in Proto-Germanic (cf. Verner's law), some words had different sounds in different grammatical forms. In MLG, there were only fossilised remnants of this "grammatischer wechsel" (grammatical change), namely for /s/ and /r/, e.g. kêsen (to choose) but koren ((they) chose), furthermore /h/ and /g/, e.g. vân < PG *fanxaną (to take hold, to catch) but gevangen < PG *fanganaz (taken hold of, caught).

- Assimilation: Sounds becoming more similar to a (usually) neighbouring sound, usually in place or manner of articulation, is very common across all languages. Early MLG did mark assimilation much more often in writing than later periods, e.g. vamme instead of van deme (of the).

- Dissimilation: In MLG, this frequently happened with /l/ vs. /r/ or /l/ vs./n/, e.g. balbêrer < barbêrer (barber), or knuflôk < kluflôk (garlic). Both forms frequently coexisted. The complete loss of a sound in proximity to an identical sound can also be explained in this way, e.g. the loss of /l/ in Willem (William) < Wilhelm.

- Metathesis: Some sounds tended to switch their places, esp. the "liquid" /l/ and /r/. Both forms may coexist, e.g. brennen vs. (metathetised) bernen (to burn).

- Gemination: In MLG, geminate consonants (which came into being by assimilaton or syncope) were no longer pronounced as such. Instead, geminate spelling was used to mark the preceding vowel as short. Many variants exist, like combinations of voiced and voiceless consonants (e.g. breifve letters, sontdage sundays). Late MLG tended to use clusters of similar consonants after short as well as long vowels, for no apparent reason, e.g. tidth for tîd (time).

- h spellings: A mute h appeared sporadically after consonants already in Old Saxon. Its use greatly increased in MLG, first in the syllable coda, where it often marked the preceding vowel as long, but later on appeared in a largely random manner. In very late times, the use of h directly after the vowel is sometimes adopted from Modern High German as a sign of vowel length.

Specific notes

(Indented notes refer to orthography, in case it differs significantly from the glyph used in the pertaining IPA symbol.)

- /m/ had a tendency to shift to /n/ in the coda, e.g. dem > den (the (dat.sg.m.)).

- Intervocalic /m/ is sometimes spelled mb, whether or not it developed from Old Saxon /mb/.

- /n/ assimilated to [ŋ] before velars /k/ and /ɣ/.

- Final /n/ often dropped out in unstressed position before consonants, e.g. hebbe(n) wi (we have), cf. Modern Dutch for a similar process. In a similar fashion, it often dropped from /ng/-clusters after unstressed vowels, esp. in Westphalian, e.g. jârlix (annually) < jârlings.

- Furthermore, /n/ had been deleted in certain coda positions several centuries before (so-called Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law) but there were many exceptions and restorations through analogy. For example, the shifted form gôs (goose < PG *gans) with an unshifted plural gense (geese) was quite common. Non-shifted forms were (and are) common in the more innovative Eastern dialects.

- /b/ as a stop [b] is only found word-initally (blôme flower, bloom), at the onset of stressed syllables (barbêrer barber) and where (historically) geminated (ebbe ebb, low tide). Its allophones in other cases are word-internal [v] and word-final [f] (e.g. drêven to drive, vs. drêf drive (n.)).

- Voiceless /f/ usually appeared word-initally (e.g. vader father), word-finally (merged with historical /b/, see above), otherwise between short vowels and nasals/liquids (also from historical /b/, e.g. gaffel fork) and in loans (e.g. straffen to tighten, from High German).

- It was mostly written v in the syllable onset, f(f) in the coda. Exceptions include loans (figûre), some proper names (Frederik), cases like gaffel as mentioned before, furthermore sporadically before u (where v would be too similar graphically) and before l and r. Sometimes, w is used for v, and ph for f.

- /w/ was originally an approximant [w~ʋ] but seems to have shifted towards a fricative later on. Its exact articulation likely differed from dialect to dialect, in many of them merging word-internally with [v], an allophone of /b/.

- In writing, w for word-internal /w/ was kept strictly separate from [v] at first, but later on, the use of w was also expanded to [v].

- The clusters /dw-/, /tw-/, /sw-/, /kw-/ were originally often written with v/u (svager brother-in-law), but later mostly shifted to a w-spelling, except for /kw-/ which kept qu due to Latin influence.

- The dentals /t/ and /d/ tended to drop out between unstressed vowels, e.g. antwer (either) instead of antwedder, and also in word-final clusters like /-ft/, /-xt/ or /-st/, e.g. often rech next to recht (law, right), schrîf next to schrîft ((he/she) writes).

- Remnants of Old Saxon /θ/ shifted via /ð/ into /d/ in the early MLG period. After /l/ and /n/, this was the case already in late Old Saxon. For /rθ/, word-final /-θ/ and some frequent words like dat (that, the (neut.)), the change also happened very early. These changes happened earliest in Westphalian, latest in North Low Saxon.

- /s/ was voiced intervocalically as [z]. Whether it was also voiced word-initially, is not fully clear. There seems to have been dialectal variation (voiceless [s] more likely for Westphalian, voiced [z] more likely for East Elbian dialects).

- Because of this variation, definitely voiceless /s/ (for example in loans from Romance or Slavic) was often written tz, cz, c etc for clarity.

- The phonemic status of /ʃ/ is difficult to determine due to the extremely irregular orthography. Its status likely differed between the dialects, with early MLG having /sk/ (Westphalian keeping it until modern times) and no phonemic /ʃ/, while e.g. East Elbian and in general many later dialects had /ʃ/ from earlier /sk/. Where there is phonemic /ʃ/, it was also often employed instead of /s/ in clusters like /sl-/, /sn-/ and the like.

- Connected with the status of /ʃ/ is the manner of articulation of /s/. Orthographic variants and some modern dialects seem to point to a more retracted, thus more sh-like pronunciation (perhaps [s̠]), esp. where there was no need to distinguish /s/ and /ʃ/. This is backed up by the situation in Westphalian today.

- /t͡s/ held at best a marginal role as a phoneme, appearing in loans or developing because of compounding or epenthesis. Confer also palatalised /k/ (next point).

- In writing, it was often marked by copious clustering, e.g. ertzcebischope (archbishop).

- /k/ before front vowels was strongly palatalised in Old Saxon (cf. the similar situation in closely related Old English) and at least parts of early MLG, as can be seen from spellings like zint for kint (child) and the variation of placename spellings, esp. in Nordalbingian and Eastphalian, e.g. Tzellingehusen for modern Kellinghusen. This palatalisation, perhaps as [c] or [t͡ɕ], persisted until the High Middle Ages and was then mostly reversed. Thus, for instance, the old affricate in the Slavic placename Liubici could be re-interpreted as a velar stop, giving the modern name Lübeck. A few words and placenames completely palatalised and shifted their velar into a sibilant (sever beetle, chafer, from PG *kebrô; the city of Celle < Old Saxon Kiellu).

- Early MLG frequently used c for /k/ (cleyn small), which became rarer later on. However, geminate k (after historically short vowels and consonants) continued to be written ck (e.g. klocke bell), more rarely kk or gk.

- gk otherwise appeared often after nasal (ringk ring, (ice) rink).

- /ks/ was often written x, esp. in the West.

- /kw-/ usually came as qu, under Latin influence (quêmen to come).

- Furthermore, after unstressed /ɪ/, /k/ often changed into /ɣ/, e.g. in the frequent derivational suffix -lik (vrüntligen friendly (infl.)) or, with final devoicing, in sich instead of sik (him-/her-/itself, themselves).

- Sometimes, ch was used for a syllable-final /k/ (ôch also, too). The h can be seen here a sign of lengthening of the preceding vowel, not of spirantisation (see "h-spelling" below).

- /ɣ/ was a fricative. Its exact articulation probably differed between the dialects. Broadly, there seems to have been on the one hand dialects that distinguished a voiced palatal [ʝ] and a voiced velar [ɣ], depending on surrounding vowels ([ʝ]: word-initially before front vowels, word-internally after front vowels; [ɣ] in those positions, but with back vowels), and on the other hand dialects that always used [ʝ] word-initially and -internally (Eastphalian, Brandenburgian, e.g. word-internally after a back vowel: voyet vogt, reeve). Nevertheless, [ʝ] was kept separate from old /j/. In the coda position, /ɣ/ came as a dorsal fricative (palatal [ç] or velar [x], depending on the preceding sound), thereby merging with /h/.

- The spelling gh was at first used almost exclusively before e or word-finally, but began to spread to other positions, notably before i. It did not indicate a different pronunciation but was part of an orthographic pattern seen in many other parts of Europe. Furtherore, in early Western traditions of MLG, sometimes ch was used for /g/ in all positions, also word-initially.

- Coda /g/ was mostly spelled ch because it completely merged with historic /h/ (see below).

- After nasals and as a geminate, /ɣ/ appeared as a stop [g], e.g. seggen to say, penninghe pennies). In contrast to modern varieties, it remained audible after a nasal. Pronouncing g word-initially as a stop [g] is likely a comparatively recent innovation under High German influence.

- gg(h) could be used for /ŋg/ in older MLG, e.g. Dudiggerode for the town of Düringerode.

- /ɣ/ frequently dropped between sonorants (except after nasal), e.g. bormêster (burgomaster, mayor) < borgermêster.

- /ɣ/ was often epenthetised between a stressed and an unstressed vowel, e.g. neigen (to sew) < Old Saxon *nāian, or vrûghe (lady, woman) < Old Saxon frūa. In Westphalian, this sound could harden into [g], e.g. eggere (eggs).

- /h/ in the onset was a glottal fricative [h], while it merged with historic /ɣ/ in the coda (see above). Word-final /h/ after consonant or long vowel frequently dropped out, e.g. hôch or hô (high). Within a compound or phrase, it often became silent (Willem < Wilhelm William).

- Onset /h/ was written h, while coda /h/ = [ç~x] was mostly written ch, but also g(h) and the like because of its merger with /ɣ/.

- Coda /h/ = [ç~x] frequently dropped between /r/ and /t/, e.g. Engelbert (a first name) with the common component -bert < Old Saxon -ber(a)ht (bright, famous). In unstressed syllables, this could also happen between a vowel and /t/, e.g. nit (not) < Old Saxon niowiht (not a thing).

- Often, h was employed for other purposes than its actual sound value, i.e. to mark vowel length (see h-spelling under "General Notes" above), to "strengthen" short words (ghân to go), to mark a vocalic onset (hvnsen our (infl.)) or vowel hiatus (sêhes (of the) lake).

- /j/ was a palatal approximant and was kept separate from [ʝ], the palatal allophone of /ɣ/.

- It was often spelled g before front vowels and was not mixed up with gh = [ʝ]. The variant y was sometimes used intervocalically (glöyen to glow).

- /r/ was likely an alveolar trill [r] or flap [ɾ], like in most traditional Low German dialects until recently. Post-vocalic /r/ sometimes dropped out, esp. before /s/.

- /l/ was originally probably velarised, i.e. a "dark l" [ɫ], at least in the coda, judging from its influence on surrounding vowels. It was however never extensively vocalised like Dutch /l/. During the MLG period, it seems to have shifted to a "clear l" in many dialects. In tends to drop out in certain usually unstressed words, esp. in Westphalian, e.g. as(se) instead of alse (as).

Vowels

This section needs expansion with: description of the vowel system, ideally acc. to Lasch (1914). You can help by adding to it. (March 2019) |

References

- ^ "m" (PDF). The Linguasphere Register. p. 219. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ Lasch, Agathe (1914). Mittelniederdeutsche Grammatik. Halle/Saale: Niemeyer. p. 5.

- ^ Köbler, Gerhard (2014). "sassisch". Mittelniederdeutsches Wörterbuch (3rd ed.). Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Cordes, Gerhard; Möhn, Dieter (1983). Handbuch zur niederdeutschen Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaft. Erich Schmidt Verlag. p. 119. ISBN 3-503-01645-7.

- ^ Bischoff, Karl (1967). Sprache und Geschichte an der mittleren Elbe und unteren Saale (in German). Köln. p. 243 f.

Wenn durch [Cryiakus] Spangenbergs Zeugnis und [Georg] Pondos Dichtungen das Niederdeutsche im ausgehenden 16. Jahrhundert im Mansfeldischen noch gesichert werden kann, dann muß es hundert Jahre früher, als Martin Luther in dieser Landschaft aufwuchs, dort noch viel fester gewesen sein. Luther hat auf der Straße in Mansfeld N i e d e r d e u t s ch gehört, und wir dürfen annehmen, daß er das mit seinen Altersgenossen auch gesprochen hat, trotz der thüringischen Mundart seines Elternhauses; mindestens wird er von ihm stark beeinflußt worden sein. Luther hat sich nicht als Meißner, was im heutigen Sprachgebrauch Obersachse wäre, und nicht als Thüringer gefühlt: ‚Sonst bin ich keiner nation so entgegen als Meichsnern vnd Thoringen. Ich bin aber kein Thoring, gehöre zun Sachsen', hat er einmal bei Tische betont. Und er scheint noch in späteren Jahren des Niederdeutschen mächtig gewesen zu sein, in [Johann] Aurifabers Aufzeichnungen vom Februar 1546 heißt es: ‚Zu dem sagete der Doctor von Wücherern, daß man jtzt spreche in Sachsen: Wer sägt, dat Wucher Sünde si, / Die hefft kein Geld, dat gläube fri. Aber ich Doctor Luther sage dagegen: Wer sägt, dat Wucher kein Sünde si, / Die hefft kein Gott, dat gläube nur fri.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Chyträus, Nathan (1582). Nomenclator latino-saxonicus. Rostock. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Biblia sacra, Ebraice, Chaldaice, Graece, Latine, Germanice, Saxonice. [...]. Nürnberg: Elias Hutter & Katharina Dietrich. 1599. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Lasch, Agathe (1914). Mittelniederdeutsche Grammatik. Halle/Saale: Niemeyer. p. 5.

- ^ Köbler, Gerhard (2014). "düde (1)". Mittelniederdeutsches Wörterbuch (3rd ed.).

- ^ Lasch, Agathe (1914). Mittelniederdeutsche Grammatik. Halle/Saale: Niemeyer. p. 5.

- ^ Köbler, Gerhard (2014). "ōsterisch". Mittelniederdeutsches Wörterbuch (3rd ed.).

- ^ Lasch, Agathe (1914). Mittelniederdeutsche Grammatik. Halle/Saale: Niemeyer. p. 6.

- ^ D. Nicholas, 2009. The Northern Lands: Germanic Europe, c.1270–c.1500. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 180-98.

- ^ Lasch, Agathe (1914). Mittelniederdeutsche Grammatik. Halle/Saale: Niemeyer. p. 1.

- ^ Lexikologie. Ein internationales Handbuch zur Natur und Struktur von Wörtern und Wortschätzen. 2. Halbband / Lexicology. An international handbook on the nature and structure of words and vocabularies. Volume 2. Walter de Gruyter, 2005, p. 1180

- ^ Hilkert Weddige, Mittelhochdeutsch: Eine Einführung. 7th ed., 2007, p. 7

- ^ Mähl, S. (2012). Low German texts from late medieval Sweden. In L. Elmevik and E. H. Jahr (eds), Contact between Low German and Scandinavian in the Late Middle Ages: 25 Years of Research, Acta Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi, 121. Uppsala: Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien för svensk folkkultur. 113–22 (at p. 118).

- ^ Lasch, Agathe (1914). Mittelniederdeutsche Grammatik. Halle/Saale: Niemeyer. pp. 129–190.

Sources

- Bible translations into German

- The Sachsenspiegel

- Reynke de Vos, a version of Reynard (at wikisource)

- Low German Incunable prints in Low German as catalogued in the Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke, including the Low German Ship of Fools, Danse Macabre and the novel Paris und Vienne

External links

- A grammar and chrestomathy of Middle Low German by Heinrich August Lübben (1882) (in German), at the Internet Archive

- A grammar of Middle Low German (1914) by Agathe Lasch (in German), at the Internet Archive

- Schiller-Lübben: A Middle Low German to German dictionary by Schiller/Lübben (1875–1881) at Mediaevum.de and at the Internet Archive

- Project TITUS, including texts in Middle Low German

- A Middle Low German to German dictionary by Gerhard Köbler (2010)

- Middle Low German influence on the Scandinavian languages