Astrology

Astrology is a group of systems, traditions, and beliefs in which knowledge of the relative positions of celestial bodies and related details is held to be useful in understanding, interpreting, and organizing information about personality, human affairs, and other terrestrial events. A practitioner of astrology is called an astrologer, or, less often, an astrologist. Historically, the term mathematicus was used to denote a person proficient in astrology, astronomy, and mathematics.[1][2]

Although the two fields share a common origin, modern astronomy is entirely distinct from astrology. Astronomy is the scientific study of astronomical objects and phenomena, the practice of astrology is concerned with the correlation of heavenly bodies (which historically involved measurement of the celestial sphere) with earthly and human affairs.[3][4] Astrology is variously considered by its proponents to be a symbolic language,[5][6] a form of art,[7] science,[7] or divination.[3][8] The scientific community generally considers astrology to be a pseudoscience[9] or superstition[10] as astrologers have failed empirical tests in controlled studies.[10][11]

The word astrology is derived from the Greek αστρολογία, from άστηρ (aster, "star") and λόγος (logos, "speech, statement, reason"). The -λογία suffix is written in English as -logy, "study" or "discipline".

| Astrology |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Traditions |

| Branches |

| Astrological signs |

| Symbols |

Beliefs

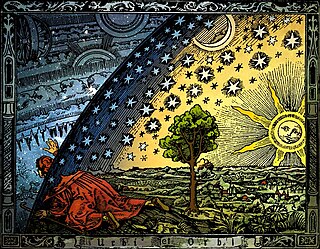

The core beliefs of astrology were prevalent in most of the ancient world and are epitomized in the Hermetic maxim "as above, so below". Tycho Brahe used a similar phrase to justify his studies in astrology: suspiciendo despicio, "by looking up I see downward". Although the principle that events in the heavens are mirrored by those on Earth was once generally held in most traditions of astrology around the world, in the West there has historically been a debate among astrologers over the nature of the mechanism behind astrology. The debate also covers whether or not celestial bodies are only signs or portents of events, or if they are actual causes of events through some sort of force or mechanism.

Although the connection between celestial mechanics and terrestrial dynamics was explored first by Isaac Newton with his development of a universal theory of gravitation, claims that the gravitational effects of the celestial bodies are what accounts for astrological generalizations are not substantiated by the scientific community, nor are they advocated by most astrologers.

A common belief held by astrologers is that the positions of certain celestial bodies either influence or correlate with human affairs. A modern explanation is that the cosmos (and especially the solar system) acts as a single unit, so that any happening in any part of it inevitably is reflected in every other part, somewhat representing chaos theory. Skeptics dispute these claims, pointing to a lack of concrete evidence of significant influence of this sort.

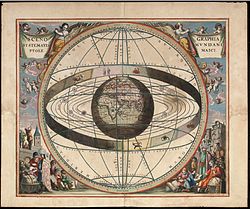

Most astrological traditions are based on the relative positions and movements of various real or construed celestial bodies and on the construction of celestial patterns as seen at the time and place of the event being studied. These are chiefly the Sun, Moon, the planets, the stars and the lunar nodes. The calculations performed in casting a horoscope involve arithmetic and simple geometry which serve to locate the apparent position of heavenly bodies on desired dates and times based on astronomical tables. The frame of reference for such apparent positions is defined by the tropical or sidereal zodiacal signs on one hand, and by the local horizon (ascendant) and midheaven on the other. This latter (local) frame is typically further divided into the twelve astrological houses.

In the past, astrologers often relied on close observation of celestial objects and the charting of their movements. Modern astrologers use data provided by astronomers which are transformed to a set of astrological tables called ephemerides, showing the changing zodiacal positions of the heavenly bodies through time.

Traditions

There are many traditions of astrology, some of which share similar features due to the transmission of astrological doctrines between cultures. Other traditions developed in isolation and hold completely different doctrines, although they too share some similar features due to the fact that they are drawing on similar astronomical sources.

Current Traditions

The main traditions used by most modern astrologers are:

Western and Indian astrology share a common ancestry as horoscopic systems of astrology (see below), and are essentially similar in content. The main difference is that Indian astrology continues to use the sidereal zodiac, linking the signs of the zodiac to their original constellations. Western astrology, on the other hand, divides the sky into twelve equal segments, beginning with the First Point of Aries, where the line of the equator and the ecliptic (the sun's path through the sky) meet at the spring equinox. This difference of approach matters because of a process called the Precession of the Equinoxes, whereby the way the earth rotates in space changes very slowly over time. This has led to a position where over the centuries, the twelve signs of the zodiac in Western astrology no longer correspond to the same part of the sky as their original constellations (and so to their Indian counterparts). In effect, in Western astrology the link between sign and constellation has been broken, whereas in Indian astrology it remains of paramount importance.

In Chinese astrology a quite different tradition has evolved. By contrast to Western and Indian astrology, the twelve signs of the zodiac do not divide the sky, but rather the equator. The Chinese evolved a system where each sign corresponds to one of twelve 'double-hours' that govern the day, and to one of the twelve months. Also most notably and uniquely, each sign of the zodiac governs a different year, and combines with a system based on the five elements of Chinese *Cosmology to give a 60 (12 x 5) year cycle. The term 'Chinese astrology' is used here for convenience, but it must be recognised that versions of the same tradition exist in Japan, Vietnam, Thailand and other East Asian countries.

In modern times, the three traditions have come into greater contact with each other. Chinese and Indian astrology have spread to the West, and awareness of Western astrology has increased in India and East Asia.

Historical Traditions

Throughout its long history, astrology has come to prominence in many countries and undergone developments and change. Therefore, there are many astrological traditions that are historically important, but have largely fallen out of use today. However, astrologers still retain an interest in them and regard them as an important resource. Historically significant traditions of astrology include:

- Babylonian astrology

- Egyptian astrology

- Hellenistic astrology

- Arab and Persian astrology

- Mesoamerican

The mesoamerican traditions are included here because they have not been widely used in their full form since Pre-Columbian times. However, there is evidence that they have survived in some form as a living tradition up to the present day, particularly among the Maya. [12] The history of Western, Chinese, and Indian astrology is discussed in the main article History of astrology .

Esoteric Traditions

Many mystic or esoteric traditions have links to astrology. In some cases, like Kabbala, this involves participants incorporating elements of astrology into their own traditions. In other cases, like divinatory tarot, many astrologers themselves have incorporated the tradition into their own practice of astrology. Esoteric traditions include, but are not limited to:

- Germanic Runes

- Kabbala

- Rosicrucian or Rose Cross

- Tarot divination

Recent Western Developments

Astrology in the Western world has diversified greatly in modern times. New movements have appeared, which have jettisoned much of traditional astrology to concentrate on different approaches, such as a greater emphasis on midpoints, or a more psychological approach. Some of its subsets include:

- Modern Tropical and Sidereal horoscopic astrology

- Hamburg School of Astrology

- Uranian astrology, subset of the Hamburg School

- Cosmobiology

- Psychological astrology or astropsychology

Horoscopic astrology

Horoscopic astrology is a very specific and complex system that was developed in the Mediterranean region and specifically Hellenistic Egypt around the late 2nd or early 1st century BCE.[13] The tradition deals with two-dimensional diagrams of the heavens created for specific moments in time. The diagram is then used to interpret the inherent meaning underlying the alignment of celestial bodies at that moment based on a specific set of rules and guidelines. One of the defining characteristics of this form of astrology that makes it distinct from other traditions is the computation of the degree of the Eastern horizon rising against the backdrop of the ecliptic at the specific moment under examination, otherwise known as the ascendant. Horoscopic astrology has been the most influential and widespread form of astrology across the world, especially in Africa, India, Europe, and the Middle East, and there are several major traditions of horoscopic astrology including Indian, Hellenistic, Medieval, and most other modern Western traditions of astrology.

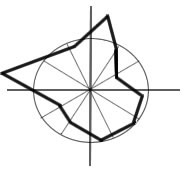

The horoscope

Central to horoscopic astrology and its branches is the calculation of the horoscope or astrological chart. This two-dimensional diagrammatic representation shows the celestial bodies' apparent positions in the heavens from the vantage of a location on Earth at a given time and place. In ancient Hellenistic astrology the ascendant demarcated the first celestial house of a horoscope. The word for the ascendant in Greek was horoskopos from which "horoscope" derives. In modern times, however, the word has come to refer to the astrological chart as a whole.

The tropical and sidereal zodiacs

The path of the Sun across the heavens as seen from Earth during a full year is called the ecliptic. This, and the nearby band of sky followed by the visible planets, is called the zodiac.

The majority of Western astrologers base their work on the tropical zodiac which evenly divides the ecliptic into 12 segments of 30 degrees each. The Sun's position at the March equinox, zero degrees Aries, marks the beginning of the zodiac. The zodiacal signs in this system bear no relation to the constellations of the same name but stay aligned to the months and seasons. The tropical zodiac is used as a historical coordinate system in astronomy.

Practitioners of the Jyotish (Hindu) astrological tradition and a minority of Western astrologers use the sidereal zodiac. This zodiac uses the same evenly divided ecliptic but approximately stays aligned to the positions of the observable constellations with the same name as the zodiacal signs. The sidereal zodiac is computed from the tropical zodiac by adding an offset called ayanamsa. This offset changes with the precession of the equinoxes.

Branches of horoscopic astrology

Traditions of horoscopic astrology can be divided into four branches which are directed towards specific subjects or purposes. Often these branches use a unique set of techniques or a different application of the core principles of the system to a different area. Many other subsets and applications of astrology are derived from these four fundamental branches.

- Natal astrology, the study of a person's natal chart to gain information about the individual and his/her life experience. This includes Judicial astrology.

- Katarchic astrology, which includes both electional and event astrology. The former uses astrology to determine the most auspicious moment to begin an enterprise or undertaking, and the latter to understand everything about an event from the time at which it took place.

- Horary astrology, used to answer a specific question by studying the chart of the moment the question is posed to an astrologer.

- Mundane or world astrology, the application of astrology to world events, including weather, earthquakes, and the rise and fall of empires or religions.

History of astrology

Origins

The origins of much of the astrological doctrine and method that would later develop in Asia, Europe, and the Middle East are found among the ancient Babylonians and their system of celestial omens that began to be compiled around the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE. This system of celestial omens later spread either directly or indirectly through the Babylonians to other areas such as India, China, and Greece where it merged with pre-existing indigenous forms of astrology. This Babylonian astrology came to Greece initially as early as the middle of the 4th century BCE, and then around the late 2nd or early 1st century BCE after the Alexandrian conquests, this Babylonian astrology was mixed with the Egyptian tradition of decanic astrology to create horoscopic astrology. This new form of astrology, which appears to have originated in Alexandrian Egypt, quickly spread across the ancient world into Europe, the Middle East and India.

Before the scientific revolution

From the classical period through the scientific revolution, astrological training played a critical role in advancing astronomical, mathematical, medical and psychological knowledge. Insofar as the interpretation of supposed astrological influences included the observation and long-term tracking of celestial objects, it was often astrologers who provided the first systematic documentation of the movements of the Sun, the Moon, the planets, and the stars. The differentiation between astronomy and astrology varied from place to place; they were indistinguishable in ancient Babylonia and for most of the Middle Ages, but separated to a greater degree in ancient Greece (see astrology and astronomy). Astrology was not always uncritically accepted before the modern era; it was often challenged by Hellenistic skeptics, church authorities and medieval thinkers.

The pattern of astronomical knowledge gained from astrological endeavours has been historically repeated across numerous cultures, from ancient India through the classical Maya civilization to medieval Europe. Given this historical contribution, astrology has been called a protoscience along with pseudosciences such as alchemy (see "Western astrology and alchemy" below).

Many prominent scientists, such as Nicholas Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, Carl Gustav Jung and others, practiced or significantly contributed to astrology.[14]

Effects on world culture

Astrology has had a profound influence over the past few thousand years on Western and Eastern cultures. In the middle ages, when even the educated of the time believed in astrology, the system of heavenly spheres and bodies was believed to reflect on the system of knowledge and the world itself below.

Language

Influenza, from medieval Latin influentia meaning influence, was so named because doctors once believed epidemics to be caused by unfavorable planetary and stellar influences. The word "disaster" comes from the Latin dis-aster meaning "bad star". Adjectives "lunatic" (Luna/Moon), "mercurial" (Mercury), "venereal" (Venus), "martial" (Mars), "jovial" (Jupiter/Jove), and "saturnine" (Saturn) are all old words used to describe personal qualities said to resemble or be highly influenced by the astrological characteristics of the planet, some of which are derived from the attributes of the ancient Roman gods they are named after.

Desire, from the Latin desiderare meaning to "long for, wish for," perhaps from the original sense "await what the stars will bring," from the phrase de sidere which translates to "from the stars," from sidus or sideris meaning "heavenly body, star, constellation".[1]

As a descriptive language for the mind

Different astrological traditions are dependent on a particular culture's prevailing mythology. These varied mythologies naturally reflect the cultures they emerge from. Images from these mythological systems are usually understandable to natives of the culture they are a part of. Most classicists think that Western astrology is dependent on Greek mythology.

Many writers, notably Geoffrey Chaucer[15][16][17] and William Shakespeare,[18][19] used astrological symbolism to add subtlety and nuance to the description of their characters' motivation(s). Often, an understanding of astrological symbolism is needed to fully appreciate such literature. Some modern thinkers, notably Carl Jung,[20] believe in its descriptive powers regarding the mind without necessarily subscribing to its predictive claims. Consequently, some regard astrology as a way of learning about one self and one's motivations. Increasingly, psychologists and historians[21] have become interested in Jung's theory of the fundamentality and indissolubility of archetypes in the human mind and their correlation with the symbols of the horoscope.

Western astrology and alchemy

Alchemy in the Western World and other locations where it was widely practiced was (and in many cases still is) allied and intertwined with traditional Babylonian-Greek style astrology; in numerous ways they were built to complement each other in the search for hidden knowledge (knowledge that is not common i.e. the occult). Astrology has used the concept of classical elements from antiquity up until the present day today. Most modern astrologers use the four classical elements extensively, and indeed it is still viewed as a critical part of interpreting the astrological chart. Traditionally, each of the seven planets in the solar system as known to the ancients was associated with, held dominion over, and "ruled" a certain metal (see also astrology and the classical elements).

The seven liberal arts and Western astrology

In medieval Europe, a university education was divided into seven distinct areas, each represented by a particular planet and known as the seven liberal arts.

Dante Alighieri speculated that these arts, which grew into the sciences we know today, fitted the same structure as the planets. As the arts were seen as operating in ascending order, so were the planets and so, in decreasing order of planetary speed, grammar was assigned to the Moon, the quickest moving celestial body, dialectic was assigned to Mercury, rhetoric to Venus, music to the Sun, arithmetic to Mars, geometry to Jupiter and astrology/astronomy to the slowest moving body, Saturn.[citation needed]

Astrology and science

By the time of Francis Bacon and the scientific revolution, newly emerging scientific disciplines acquired a method of systematic empirical induction validated by experimental observations, which led to the scientific revolution.[22] At this point, astrology and astronomy began to diverge; astronomy became one of the central sciences while astrology was increasingly viewed as an occult science or superstition by natural scientists. This separation accelerated through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[23]

Within the contemporary scientific community, astrology is generally labeled as a pseudoscience,[9][24] and it has been criticized as being unscientific both by scientific bodies and by individual scientists.[25][26] In 1975, the American Humanist Association published one of the most widely known modern criticisms of astrology, characterizing those who continue to have faith in the subject as doing so "in spite of the fact that there is no verified scientific basis for their beliefs, and indeed that there is strong evidence to the contrary".[27] Astronomer Carl Sagan did not sign the statement, noting that, while he felt astrology lacked validity, he found the statement's tone authoritarian. He suggested that the lack of a causal mechanism for astrology was relevant but not in itself convincing.[28][29]

Although astrology has had no accepted scientific standing for some time, it has been the subject of much research among astrologers since the beginning of the twentieth century. In his landmark study of twentieth-century research into natal astrology, vocal astrology critic Geoffrey Dean noted and documented the burgeoning research activity, primarily within the astrological community.[30]

Claims about obstacles to research

Astrologers have argued that there are significant obstacles in carrying out scientific research into astrology today, including funding,[31][32][33] lack of background in science and statistics by astrologers,[31] and insufficient expertise in astrology by research scientists.[31][32][33] There are only a handful of journals dealing with scientific research into astrology (i.e. astrological journals directed towards scientific research or scientific journals publishing astrological research). Some astrologers have argued that few practitioners today pursue scientific testing of astrology because they feel that working with clients on a daily basis provides a personal validation for them.[33][34]

Another argument made by astrologers is that most studies of astrology do not reflect the nature of astrological practice and that existing experimental methods and research tools are not adequate for studying this complex discipline.[35][36] Some astrology proponents claim that the prevailing attitudes and motives of many opponents of astrology introduce conscious or unconscious bias in the formulation of hypotheses to be tested, the conduct of the tests, and the reporting of results.[31]

Mechanism

Many critics claim that a central problem to astrology is the lack of evidence for a scientifically defined mechanism by which celestial objects can supposedly influence terrestrial affairs.[37] Astrologers claim that a lack of an explanatory mechanism would not scientifically invalidate astrological findings.[31] Though physical mechanisms are still among the proposed theories of astrology,[38][39] few modern astrologers believe in a direct causal relationship between heavenly bodies and earthly events.[33] Some have posited acausal, purely correlative, relationships between astrological observations and events, such as the theory of synchronicity[40] proposed by Jung. Astrophysicist Victor Mansfield suggests that astrology should draw inspiration from quantum physics.[41] Others have posited a basis in divination.[42] Still others have argued that empirical correlations can stand on their own epistemologically, and do not need the support of any theory or mechanism.[31] To some observers, these non-mechanistic concepts raise serious questions about the feasibility of validating astrology through scientific testing, and some have gone so far as to reject the applicability of the scientific method to astrology almost entirely.[31][7] Some astrologers, on the other hand, believe that astrology is amenable to the scientific method, given sufficiently sophisticated analytical methods, and they cite pilot studies they claim support this view.[43] Consequently, several astrologers have called for or advocated continuing studies of astrology based on statistical validation.[44]

Research claims and counter-claims

Several individuals, most notably French psychologist and statistician Michel Gauquelin, claimed to have found correlations between some planetary positions and certain human traits such as vocations. Gauquelin's most widely known claim is known as the Mars effect, which is said to demonstrate a correlation between the planet Mars occupying certain positions in the sky more often at the birth of eminent sports champions than at the birth of ordinary people. Since its original publication in 1955, the Mars effect has been the subject of studies claiming to refute it,[45][46] and studies claiming to support and/or expand the original claims,[47][48][49] but neither the claims nor the counterclaims have received mainstream scientific notice.

Besides the claims of the Mars effect, astrological researchers claim to have found statistical correlations for physical attributes,[50] accidents,[51][52] personal and mundane events,[53][54] social trends such as economics[55][56] and large geophysical patterns.[57] None of these claims, however, have been published in a mainstream scientific journal.

The scientific community, where it has commented, claims that astrology has repeatedly failed to demonstrate its effectiveness in numerous controlled studies.[10] Effect size studies in astrology conclude that the mean accuracy of astrological predictions is no greater than what is expected by chance, and astrology's perceived performance has disappeared on critical inspection.[58][59] When tested against personality tests, astrologers have shown a consistent lack of agreement with these tests. One such double-blind study in which astrologers attempted to match birth charts with results of a personality test, which was published in the reputable peer-reviewed scientific journal Nature, claimed to refute astrologers' assertions that they can solve clients' personal problems by reading individuals' natal charts. The study concluded that astrologers had no special ability to interpret personality from astrological readings.[60][61] Another study that used a personality test and a questionnaire contended that some astrologers failed to predict objective facts about people or agree with each other's interpretations.[62] When testing for cognitive, behavioral, physical and other variables, one study of astrological "time twins" claimed that human characteristics are not molded by the influence of the Sun, Moon and planets at the time of birth.[59][63] Skeptics of astrology also suggest that the perceived accuracy of astrological interpretations and descriptions of one's personality can be accounted for by the fact that people tend to exaggerate positive 'hits' and overlook whatever does not fit, especially when vague language is used.[59] They also claim that statistical research is often wrongly seen as evidence for astrology due to uncontrolled artifacts.[64]

See also

Notes and references

- ^ "Galileo, Astrology and the Scientific Revolution: Another Look". Stanford. Retrieved 2006-07-17.

- ^ "Ultralingua Latin-English Dictionary". Ultralingua.Net. Retrieved 2006-07-17.

- ^ a b "Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Meriam-Webster. Retrieved 2006-07-19.

- ^ "Compact Oxford English Dictionary". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2006-07-19.

- ^ Michael Star. "Astrology FAQ, Basics for Beginners and Students of Astrology". Retrieved 2006-07-17.

- ^ Alain Nègre. "A Transdisciplinary Approach to Science and Astrology". Retrieved 2006-07-17.

- ^ a b c Nick Campion. "Nick Campion's Online Astrology Resource: Science & Astrology". Retrieved 2006-07-17.

- ^ ""astrology." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006". Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2006-07-17.

- ^ a b "WordNet 2.1". Princeton. Retrieved 2006-07-05.

- ^ a b c "Activities With Astrology". Astronomical society of the Pacific.

- ^ "The case for and against astrology". Rudolf.H.Smit.

- ^ Ronald Wright "Time Among the Maya" Abacus Books, London 1989

- ^ David Pingree - From Astral Omens to Astrology from Babylon to Bikaner, Roma: Istituto Italiano per L'Africa e L'Oriente, 1997. Pg. 26.

- ^ Bruce Scofield. "Were They Astrologers? — Big League Scientists and Astrology". The Mountain Astrologer magazine. Retrieved 2006-07-17.

- ^ A. Kitson. "Astrology and English literature". Contemporary Review, Oct 1996. Retrieved 2006-07-17.

- ^ M. Allen, J.H. Fisher. "Essential Chaucer: Science, including astrology". University of Texas, San Antonio. Retrieved 2006-07-17.

- ^ A.B.P. Mattar; et al. "Astronomy and Astrology in the Works of Chaucer" (PDF). University of Singapore. Retrieved 2006-07-17.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ P. Brown. "Shakespeare, Astrology, and Alchemy: A Critical and Historical Perspective". The Mountain Astrologer, Feb/Mar 2004.

- ^ F. Piechoski. "Shakespeare's Astrology".

- ^ Carl G. Jung, "Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious," excerpted in The Basic Writings of C.G. Jung (Modern Library, repr. 1993), 362-363.

- ^ Richard Tarnas, Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View Viking (New York, 2006.) ISBN 0-670-03292-1.

- ^ "The scientific revolution".

- ^ Jim Tester, A History of Western Astrology (Ballantine Books, 1989), 240ff.

- ^ "Astronomical Pseudo-Science: A Skeptic's Resource List". Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

- ^ Richard Dawkins. "The Real Romance in the Stars". The Independent, December 1995.

- ^ "British Physicist Debunks Astrology in Indian Lecture". Associated Press.

- ^ "Objections to Astrology: A Statement by 186 Leading Scientists". The Humanist, September/October 1975.

- ^ Sagan, Carl. "Letter." The Humanist 36 (1976): 2

- ^ Mariapaula Karadimas. "Astrology: What it is and what it isn't,". The Peak Publications Society.

- ^ G. Dean et al, Recent Advances in Natal Astrology: A Critical Review 1900-1976. The Astrological Association (England 1977)

- ^ a b c d e f g M. Harding. "Prejudice in Astrological Research". Correlation, Vol 19(1). Cite error: The named reference "Harding" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b H.J. Eysenck & D.K.B. Nias, Astrology: Science or Superstition? Penguin Books (1982) ISBN 0-14-022397-5

- ^ a b c d G. Phillipson, Astrology in the Year Zero. Flare Publications (London, 2000) ISBN 0-9530261-9-1

- ^ K. Irving. "Science, Astrology and the Gauquelin Planetary Effects".

- ^ M. Urban-Lurain, Introduction to Multivariate Analysis, Astrological Research Methods, Volume 1: An ISAR Anthology. International Society for Astrological Research (Los Angeles 1995) ISBN 0-9646366-0-3

- ^ G. Perry, How do we Know What we Think we Know? From Paradigm to Method in Astrological Research, Astrological Research Methods, Volume 1: An ISAR Anthology. International Society for Astrological Research (Los Angeles 1995) ISBN 0-9646366-0-3

- ^ "Horoscopes Versus Telescopes: A Focus on Astrology". Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

- ^ Dr. P. Seymour, Astrology: The evidence of Science. Penguin Group (London, 1988) ISBN 0-14-019226-3

- ^ Frank McGillion. "The Pineal Gland and the Ancient Art of Iatromathematica".

- ^ Maggie Hyde, Jung and Astrology. The Aquarian Press (London, 1992) p. 24-26.

- ^ Victor Mansfield. "An Astrophysicist's Sympathetic and Critical View of Astrology".

- ^ Geoffrey Cornelius, The Moment of Astrology. Utsav Arora, another meditation research specialist and astrologer, argues, "if 100% accuracy were to be the benchmark, we shoud be closing down and shutting all hospitals, medical labs. Scientific medical equipment and drugs have a long history of errors and miscalculations. Same is the case with computers and electronic. We dont refute electronic gadgets and equipment just because it fails but we work towards finding cures for the errors." The Wessex Astrologer (Bournemouth, 2003.)

- ^ D. Cochrane, Towards a Proof of Astrology: An AstroSignature for Mathematical Ability International Astrologer ISAR Journal Winter-Spring 2005, Vol 33, #2

- ^ M. Pottenger (ed), Astrological Research Methods, Volume 1: An ISAR Anthology. International Society for Astrological Research (Los Angeles 1995) ISBN 0-9646366-0-3

- ^ Benski, C. et al. 1996. The "Mars Effect": A French Test of Over 1000 Sports Champions.

- ^ Zelen, M., P. Kurtz, and G. Abell. 1977. Is there a Mars effect? The Humanist 37 (6): 36-39.

- ^ Suitbert Ertel. "Raising the Hurdle for the Athletes' Mars Effect: Association Co-Varies With Eminence". Journal of Scientific Exploration.

- ^ Ken Irving. "Discussion of Mars eminence effect". Planetos.

- ^ N. Kollerstrom. "How Ertel rescued the Gauquelin effect" (PDF).

- ^ O'Neil, Mike. "The Switching Control Applied to Hill and Thompson's Redhead Data" Correlation, vol. 11(1) p. 24 (1991)

- ^ Ridgley, Sara K. "Astrologically Predictable Patterns in Work Related Injuries". Kosmos, XXII [3], 1993, pp.21-30.

- ^ N. Kollerstrom. Investigating Aspects, Astrological Research Methods, Volume 1: An ISAR Anthology. International Society for Astrological Research (Los Angeles 1995) ISBN 0-9646366-0-3

- ^ K. Gillman. "The Effect of Planets in their own Signs". Considerations X.4.

- ^ Castille, Didier. "Sunny Day for a Wedding" (PDF). Les cahiers du RAMS.

- ^ R. Merriman, Research for Financial Astrology Studies, Astrological Research Methods, Volume 1: An ISAR Anthology. International Society for Astrological Research (Los Angeles 1995) ISBN 0-9646366-0-3

- ^ Yuan, Kathy; Zheng, Lu; Zhu, Qiaoqiao. "Are Investors Moonstruck?" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Johnston, Brian T. "Planetary Aspects and Terrestrial Earthquakes".

- ^ Rudolf.H.Smit. "How astrology compares with other approaches".

- ^ a b c Dean and Kelly. "Is Astrology Relevant to Consciousness and Psi?" (PDF).

- ^ Shawn Carlson. "A double-blind test of astrology". Nature, 318, 419 - 425 (05 December 1985).

- ^ "Skeptical Studies in Astrology, report of Shawn Carlson's double-blind test of astrology published in Nature". Tom Howell Productions.

- ^ Rob Nanninga. "The Astrotest - Correlation". Northern Winter, 1996/97, 15(2), p. 14-20.

- ^ Robert Matthews (2003-08-17). "Comprehensive study of 'time twins' debunks astrology". London Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Geoffery Dean. "Artifacts in data often wrongly seen as evidence for astrology".

Further reading

- David Berlinski, The Secrets of the Vaulted Sky: Astrology and the Art of Prediction. Harcourt (USA, October 2003) ISBN 0-15-100527-3.

- Geoffrey Cornelius, Moment of Astrology. Wessex Astrologer Ltd. (UK, August 2005) ISBN 1-902405-11-0.

- Nicholas De Vore, Encyclopedia of Astrology. Astrology Classics (New York, 2005) ISBN 1-933303-09-3.

- J. C. Eade, The Forgotten Sky: A Guide to Astrology in English Literature. Oxford University Press (USA, 1984) ISBN 0-19-812813-4.

- Abraham Ibn Ezra, The Beginning of Wisdom. ARHAT Publications (USA, 1998) ISBN 0-9662266-4-X.

- Michel Gauquelin, Cosmic Influences on Human Behavior. Aurora Press (Santa Fe, NM; June 1985) ISBN 0-943358-23-X.

- Michel Gauquelin, The Scientific Basis of Astrology. Stein and Day Publishers (New York, 1970) ISBN 0-8128-1350-2.

- Ann Geneva, Astrology and The Seventeenth Century Mind: William Lilly and the Language of the Stars. Manchester University Press (Manchester, UK; 1995) ISBN 0-7190-4154-6.

- Robert Hand, Horoscope Symbols. Schiffer Publications (Altgen, PA; March 1987) ISBN 0-914918-16-8.

- Johannes Kepler, The Harmony of the World (1619) (Latin: Harmonice Mundi). American Philosophical Society (USA, April 1997). ISBN 0-87169-209-0.

- Johannes Kepler, On The More Certain Fundamentals of Astrology (1601) (Latin: De Fundamentis Astrologiae Certioribus). Kessinger Publishing (USA, January 2003) ISBN 0-7661-3375-3.

- William R. Newman & Anthony Grafton (Editors), Secrets of Nature: Astrology and Alchemy in Early Modern Europe. MIT Press (Cambridge, MA; March 2006) ISBN 0-262-64062-7.

- Garry Phillipson, Astrology in the Year Zero. Flare Publications (London, 2000) ISBN 0-9530261-9-1.

- Ptolemy, Tetrabiblos. Harvard University Press (Cambridge, MA; October 1980) ISBN 0-674-99479-5.

- Francesca Rochberg, The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture. Cambridge University Press (Cambridge, UK; 2004) ISBN 0-521-83010-9.

- Laura A. Smoller, History, Prophecy, and the Stars: The Christian Astrology of Pierre D'Ailly, 1350-1420. Princeton University Press (Princeton, NJ; 1994) ISBN 0-691-08788-1.

- Richard Tarnas, Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View. Viking (New York, 2006) ISBN 0-670-03292-1.

- Theodore Otto Wedel, Astrology in the Middle Ages. Dover Publications (Mineola, NY; 2005) ISBN 0-486-43642-X.

External links

- General

- History

- Skyscript, a modern look at classical astrology.

- Astrology: Between Religion and the Empirical, a treatise on astrology by Dr. Gustav-Adolf Schoener, translated by Shane Denson.

- History of Astrology in the Renaissance, series of articles on astrology and its influence in the Renaissance.

- Astrologia, article in Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman antiquities

- Hellenistic Astrology, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on Hellenistic astrology and its interaction with philosophical schools.

- Astrology & Astronomy in Chaucer's Time from Harvard University professor L.D. Benson.

- Extensive Timeline -- The History of Astrology from the Astrologisk Museum in Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Schools

- Kepler College of Astrological Arts and Sciences, based in Seattle, USA, Kepler College is the only college in the western hemisphere authorized to issue A.A., B.A., and M.A degrees in Astrological Studies.

- The Sophia Centre, based near Bath, England, the centre is a department of School of Historical and Cultural Studies at Bath Spa University College, offering a MA in Cultural Astronomy and Astrology and supervising postgraduate research.

- Faculty of Astrological Studies, its diploma, the D.F.Astrol.S., is among the most highly valued and recognised international qualifications.

- The New Yuthok Institute, based in Milan, Italy offers a six-year course in Tibetan astrology, divided in 3 levels. Courses are given in English and Italian.

- Associations

- Astrology and science

- Astrology and Science, a critical look at astrology and science.

- Astrology in the Year Zero, evaluation of astrology; linked to Garry Phillipson's book of the same name.

- The Astrotest, an account of a test of the predictive power of astrology, with references to other experiments.

- The True Disbelievers by Richard Kamann and Marcello Truzzi. A report of alleged internal events at CSICOP regarding their own claimed confirmation of M. Gauquelin's 'Mars Effect'.

- The Real Romance in the Stars, a critical view of astrology by Richard Dawkins.

- Is Astrology a Pseudoscience?

- Astrology and religion

- Types of astrology

- Dane Rudhyar archival project, index of articles by astrologer Dane Rudhyar.

- Jolly Creations, Vedic astrology resources.

- The Uranian Institute, comprehensive Uranian astrology website.

- Index of articles about Jyotisha or Vedic astrology

- Information on Vedic astrology

- Tibetan astrology

- Tools and software

- Astrolabe Software, online service used to calculate an astrological chart.

- A comprehensive astrological dictionary

- Astrolog 5.40, an open source, cross-platform, and free astrology application.

- Astrology for Windows, astrology application for Microsoft Windows.

- Configuration Hunter, freeware Windows astrology application for searching configurations and planetary aspects.

- Astrodienst, provides an online tool for astrological chart calculation as well as various reports.

- Astrologie Info, online chart calculation in graphic/text mode and interactive Moon calendar.

- Natal and relationship reports

- http://www.lunarcal.org

- Relationships Analyst, based on the Church of Light's Cosmodynes Theory.

- http://www.onereed.com/

- http://www.chaosastrology.com/

- Vedic Astrology, natal chart representation by way of Indian astrology.