Glyphosate: Difference between revisions

Gandydancer (talk | contribs) →Soil degradation and effects on micro-organism and worms: no changes other than move para re soil up |

Gandydancer (talk | contribs) /* Soil degradation and effects on micro-organism and worms *there is really nothing worth noting re worms, etc. here and I am deleting it--the soil info can go into another section/ |

||

| Line 225: | Line 225: | ||

Monsanto and other companies produce glyphosate products with alternative surfactants that are specifically formulated for aquatic use, for example the Monsanto products "Biactive" and "AquaMaster".<ref name="url_backrounder_aquatic">{{cite web | url = http://www.monsanto.com/products/Documents/glyphosate-background-materials/bkg_amphib_05a.pdf | title =Response to "The impact of insecticides and herbicides on the biodiversity and productivity of aquatic communities" | date = 2005-04-01 | format = PDF | work = Backgrounder | publisher = Monsanto Company }}</ref> <ref name="url_backgrounder_Aquatic_Australia">{{cite web | url = http://www.monsanto.com/products/Documents/glyphosate-background-materials/gly_austfrog_bkg.pdf | title = Aquatic Use of Glyphosate Herbicides in Australia | date = 2003-05-01 | format = PDF | work = Backgrounder | publisher = Monsanto Company }}</ref> |

Monsanto and other companies produce glyphosate products with alternative surfactants that are specifically formulated for aquatic use, for example the Monsanto products "Biactive" and "AquaMaster".<ref name="url_backrounder_aquatic">{{cite web | url = http://www.monsanto.com/products/Documents/glyphosate-background-materials/bkg_amphib_05a.pdf | title =Response to "The impact of insecticides and herbicides on the biodiversity and productivity of aquatic communities" | date = 2005-04-01 | format = PDF | work = Backgrounder | publisher = Monsanto Company }}</ref> <ref name="url_backgrounder_Aquatic_Australia">{{cite web | url = http://www.monsanto.com/products/Documents/glyphosate-background-materials/gly_austfrog_bkg.pdf | title = Aquatic Use of Glyphosate Herbicides in Australia | date = 2003-05-01 | format = PDF | work = Backgrounder | publisher = Monsanto Company }}</ref> |

||

In 2001 the Monsanto product Vision® was studied in a forest wetlands site in Canada. Substantial mortality occurred only at concentrations exceeding the expected environmental concentrations as calculated by Canadian regulatory authorities. While it was found that site factors such as pH and suspended sediments substantially affected the toxicity in the amphibian larvae tested, overall, "results suggest that the silvicultural use of Vision herbicide in accordance with the product label and standard Canadian environmental regulations should have negligible adverse effects on sensitive larval life stages of native amphibians."<ref name="pmid15095877">{{cite journal | author = Wojtaszek BF, Staznik B, Chartrand DT, Stephenson GR, Thompson DG | title = Effects of Vision® herbicide on mortality, avoidance response, and growth of amphibian larvae in two forest wetlands | journal = Environ. Toxicol. Chem. | volume = 23 | issue = 4 | pages = 832–42 | year = 2004 | month = April | pmid = 15095877 | doi = 10.1897/02-281 }}</ref> |

In 2001 the Monsanto product Vision® was studied in a forest wetlands site in Canada. Substantial mortality occurred only at concentrations exceeding the expected environmental concentrations as calculated by Canadian regulatory authorities. While it was found that site factors such as pH and suspended sediments substantially affected the toxicity in the amphibian larvae tested, overall, "results suggest that the silvicultural use of Vision herbicide in accordance with the product label and standard Canadian environmental regulations should have negligible adverse effects on sensitive larval life stages of native amphibians."<ref name="pmid15095877">{{cite journal | author = Wojtaszek BF, Staznik B, Chartrand DT, Stephenson GR, Thompson DG | title = Effects of Vision® herbicide on mortality, avoidance response, and growth of amphibian larvae in two forest wetlands | journal = Environ. Toxicol. Chem. | volume = 23 | issue = 4 | pages = 832–42 | year = 2004 | month = April | pmid = 15095877 | doi = 10.1897/02-281 }}</ref> |

||

==== Soil degradation and effects on micro-organism and worms ==== |

|||

A 2009 study using a RoundUp formulation has concluded that absorption into plants delays subsequent soil-degradation, and can increase glyphosate persistence in soil from two to six times.<ref name="pmid19625069">{{cite journal | author = Doublet J, Mamy L, Barriuso E | title = Delayed degradation in soil of foliar herbicides glyphosate and sulcotrione previously absorbed by plants: consequences on herbicide fate and risk assessment | journal = Chemosphere | volume = 77 | issue = 4 | pages = 582–9 | year = 2009 | month = October | pmid = 19625069 | doi = 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.06.044 }}</ref> |

|||

A laboratory study published in 1992 indicated that glyphosate formulations could harm [[earthworm]]s<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/0038-0717(92)90180-6 |title=Effect of repeated low doses of biocides on the earthworm Aporrectodea caliginosa in laboratory culture |year=1992 | author = Springett JA, Gray RAJ | journal = Soil Biology and Biochemistry | volume = 24 | issue = 12 | pages = 1739 }}</ref> and beneficial [[insect]]s.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Results of the fifth joint pesticide testing programme carried out by the IOBC/WPRS-Working Group 'Pesticides and beneficial organisms' | year = 1991 | author = Hassan SA, Bigler F, Bogenschütz H, Boller E, Brun J, Calis JNM, Chiverton P, Coremans-Pelseneer J, Duso C | journal = Entomophaga | volume = 36 | pages = 55–67 | doi = 10.1007/BF02374636 }}</ref> However, the reported effect of glyphosate on earthworms has been criticized.<ref name=Giesy2000 /> The results conflict with results from field studies where no effects were noted for the number of nematodes, mites, or springtails after treatment with Roundup at 2 kilograms active ingredient per hectare.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Preston CM, Trofymow JA |year=1989 |title=Effects of glyphosate (Roundup) on biological activity of forest soils |journal=Proceedings of the Carnation Creek Workshop |pages=122–40 |isbn=0-7726-0917-9 |url=http://www.for.gov.bc.ca/hfd/pubs/Docs/Frr/Frr063.htm}}</ref> |

|||

==== Effect on plant health ==== |

==== Effect on plant health ==== |

||

Revision as of 10:19, 6 September 2013

It has been suggested that this article should be split into articles titled Glyphosate and Roundup. (discuss) (August 2013) |

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

N-(phosphonomethyl)glycine

| |

| Other names

2-[(phosphonomethyl)amino]acetic acid

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.012.726 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C3H8NO5P | |

| Molar mass | 169.073 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Density | 1.704 (20 °C) |

| Melting point | 184.5 °C |

| Boiling point | decomposes at 187 °C |

| 1.01 g/100 mL (20 °C) | |

| log P | −2.8 |

| Acidity (pKa) | <2, 2.6, 5.6, 10.6 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H318, H411 | |

| P273, P280, P305+P351+P338, P310, P501 | |

| Flash point | non-flammable |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Glyphosate (N-(phosphonomethyl)glycine) is a broad-spectrum systemic herbicide used to kill weeds, especially annual broadleaf weeds and grasses known to compete with commercial crops grown around the globe. It was discovered to be a herbicide by Monsanto chemist John E. Franz in 1970.[3] Monsanto brought it to market in the 1970s under the trade name "Roundup", and Monsanto's last commercially relevant United States patent expired in 2000.

Glyphosate was quickly adopted by farmers, even more so when Monsanto introduced glyphosate-resistant crops, enabling farmers to kill weeds without killing their crops. In 2007 glyphosate was the most used herbicide in the United States agricultural sector, with 180 to 185 million pounds (82,000 to 84,000 tonnes) applied, and the second most used in home and garden market where users applied 5 to 8 million pounds (2,300 to 3,600 tonnes); additionally industry, commerce and government applied 13 to 15 million pounds (5,900 to 6,800 tonnes).[4] With its heavy use in agriculture, weed resistance to glyphosate is a growing problem. While glyphosate and formulations such as Roundup have been approved by regulatory bodies worldwide and are widely used, concerns about their effects on humans and the environment persist.[5]

Glyphosate's mode of action is to inhibit an enzyme involved in the synthesis of the aromatic amino acids tyrosine, tryptophan and phenylalanine. It is absorbed through foliage and translocated to growing points. Because of this mode of action, it is only effective on actively growing plants; it is not effective as a pre-emergence herbicide.

Some crops have been genetically engineered to be resistant to it (i.e. "Roundup Ready", also created by Monsanto Company). Such crops allow farmers to use glyphosate as a post-emergence herbicide against both broadleaf and cereal weeds, but the development of similar resistance in some weed species is emerging as a costly problem. Soy was the first "Roundup Ready" crop.

Discovery

Glyphosate was first discovered to have herbicidal activity in 1970 by John E. Franz, while working for Monsanto.[6] Franz received the National Medal of Technology in 1987[7] and the Perkin Medal for Applied Chemistry[8] in 1990 for his discoveries. Franz was then inducted into the National Inventor's Hall of Fame in 2007.[9]

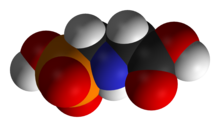

Chemistry

Glyphosate is an aminophosphonic analogue of the natural amino acid glycine, and the name is a contraction of gly(cine) phos(phon)ate. The molecule has several dissociable hydrogens, especially the first hydrogen of the phosphate group. The molecule tends to exist as a zwitterion where a phosphonic hydrogen dissociates and joins the amine group. Glyphosate is soluble in water to 12 g/L at room temperature.

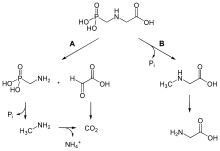

Main deactivation path is hydrolysis to aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA).[10]

Biochemistry

Glyphosate kills plants by interfering with the synthesis of the aromatic amino acids phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan. It does this by inhibiting the enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS), which catalyzes the reaction of shikimate-3-phosphate (S3P) and phosphoenolpyruvate to form 5-enolpyruvyl-shikimate-3-phosphate (ESP).[11]

ESP is subsequently dephosphorylated to chorismate, an essential precursor for the amino acids mentioned above.[12] These amino acids are used in protein synthesis and to produce secondary metabolites such as folates, ubiquinones and naphthoquinone.

X-ray crystallographic studies of glyphosate and EPSPS show that glyphosate functions by occupying the binding site of the phosphoenolpyruvate, mimicking an intermediate state of the ternary enzyme substrates complex.[13][14]

The enzyme that glyphosate inhibits, EPSPS, is found only in plants and micro-organisms. EPSPS is not present in animals, which instead obtain aromatic amino acids from their diet.[15]

Glyphosate has also been shown to inhibit other plant enzymes,[16][17] and also has been found to affect animal enzymes.[18]

Glyphosate is absorbed through foliage. Because of this mode of action, it is only effective on actively growing plants; it is not effective in preventing seeds from germinating.

Use

Glyphosate is effective in killing a wide variety of plants, including grasses, broadleaf, and woody plants. It has a relatively small effect on some clover species.[19] By volume, it is one of the most widely used herbicides.[20] It is commonly used for agriculture, horticulture, viticulture and silviculture purposes, as well as garden maintenance (including home use).[20][21] Prior to harvest glyphosate is used for crop desiccation (siccation) to increase the harvest yield.[22]

In many cities, glyphosate is sprayed along the sidewalks and streets, as well as crevices in between pavement where weeds often grow. However, up to 24% of glyphosate applied to hard surfaces can be run off by water.[23] Glyphosate contamination of surface water is highly attributed to urban use.[24] Glyphosate is used to clear railroad tracks and get rid of unwanted aquatic vegetation.[22]

Glyphosate is one of a number of herbicides used by the United States and Colombian governments to spray coca fields through Plan Colombia. Its effects on legal crops and effectiveness in fighting the war on drugs have been disputed.[25] There are reports that widespread application of glyphosate in attempts to destroy coca crops in South America have resulted in the development of glyphosate-resistant strains of coca nicknamed "Boliviana Negra", which have been selectively bred to be both "Roundup Ready" and larger and higher yielding than the original strains of the plant.[26] However, there are no reports of glyphosate-resistant coca in the peer-reviewed literature. In addition, since spraying of herbicides is not permitted in Colombian national parks, this has encouraged coca growers to move into park areas, cutting down the natural vegetation, and establishing coca plantations within park lands.[27]

Formulations and tradenames

This section needs expansion with: examples of formulations of glyphosate – what are other surfactants and adjuvants? what are their qualities? Which are best for various purposes of farmers? What are the risks of those chemicals? There are many.. You can help by adding to it. (September 2012) |

Glyphosate is marketed in the United States and worldwide by many agrochemical companies, in different solution strengths and with various adjuvants, under many tradenames: Accord, Aquaneat, Aquamaster, Bronco, Buccaneer, Campain, Clearout 41 Plus, Clear-up, Expedite, Fallow Master, Genesis Extra I, Glyfos Induce, Glypro, GlyStar Induce, GlyphoMax Induce, Honcho, JuryR, Landmaster, MirageR, Pondmaster, Protocol, Prosecutor, Ranger, Rascal, Rattler, Razor Pro, Rodeo, Roundup, I, Roundup Pro Concentrate, Roundup UltraMax, Roundup WeatherMax, Silhouette, Touchdown IQ.[28][29][30]

Manufacturers include Bayer, Dow AgroSciences, Du Pont, Cenex/Land O’Lakes, Helena, Monsanto, Platte, Riverside/Terra, and Zeneca.[30]

Glyphosate is an acid molecule, but it is formulated as a salt for packaging and handling. Various salt formulations include isopropylamine, diammonium, monoammonium, or potassium as the counterion. Some brands include more than one salt. Some companies report their product as acid equivalent (ae) of glyphosate acid, or some report it as active ingredient (ai) of glyphosate plus the salt, and others report both. In order to compare performance of different formulations it is critical to know how the products were formulated. Since the salt does not contribute to weed control and different salts have different weights, the acid equivalent is a more accurate method of expressing, and comparing concentrations.[31] Adjuvant loading refers to the amount of adjuvant[32][33] already added to the glyphosate product. Fully loaded products contain all the necessary adjuvants, including surfactant, some contain no adjuvant system; while other products contain only a limited amount of adjuvant (minimal or partial loading) and additional surfactants must be added to the spray tank before application.[31] As of 2000 (just before Monsanto's patent on glyphosate expired) there were 400 commercial adjuvants from over 34 different companies available for use in commercial agriculture.[34][35]

Products are supplied most commonly in formulations of 120, 240, 360, 480 and 680 g active ingredient per litre. The most common formulation in agriculture is 360 g, either alone or with added cationic surfactants.

For 360 g formulations, European regulations allow applications of up to 12 litres per hectare for control of perennial weeds such as couch grass. More commonly, rates of 3 litres per hectare are practiced for control of annual weeds between crops.[36]

Monsanto

Monsanto developed and patented the glyphosate molecule in the 1970s, and has marketed it as Roundup since 1973. It retained exclusive rights in the United States until its United States patent expired in September, 2000.

As of 2009, sales of these herbicide products represented about 10% of Monsanto's revenue due to competition from other producers of other glyphosate-based herbicides;[37] their Roundup products (which include GM seeds) represents about half of Monsanto's yearly revenue.[38]

The active ingredient of the Monsanto herbicides is the isopropylamine salt of glyphosate. Another important ingredient in some formulations is the surfactant POEA (polyethoxylated tallow amine), which has been found to be highly toxic to animals and to humans.[39][40][41][42]

Monsanto also produces seeds which grow into plants genetically engineered to be tolerant to glyphosate. The genes contained in these seeds are patented. Such crops allow farmers to use glyphosate as a post-emergence herbicide against most broadleaf and cereal weeds. Soy was the first glyphosate resistance crop.

In November 2009, a French environment group (MDRGF) accused Monsanto of using chemicals in Roundup formulations not disclosed to the country's regulatory bodies, and demanded the removal of those products from the market.[43][44]

Toxicity

Glyphosate is the active ingredient in herbicide formulations containing it. However, in addition to glyphosate salts, commercial formulations of glyphosate contain additives such as surfactants which vary in nature and concentration. Laboratory toxicology studies have suggested that other ingredients in combination with glyphosate may have greater toxicity than glyphosate alone.[45] Toxicologists have studied glyphosate alone, additives alone, and formulations.

Glyphosate toxicity

Glyphosate has a United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Toxicity Class of III (on a I to IV scale, where IV is least dangerous) for oral and inhalation exposure.[46] Thus, as with other herbicides, the EPA requires that products containing glyphosate carry a label that warns against oral intake, mandates the use of protective clothing, and instructs users not to re-enter treated fields for at least 4 hours.[46][47] Glyphosate does not bioaccumulate in animals. It is excreted in urine and faeces. It breaks down variably quickly depending on the particular environment. Health, environmental and food chain effects from alteration of gut flora by wide use of glyphosate are largely unexplored.[48][49][50]

Human

Human acute toxicity is dose related. Acute fatal toxicity has been reported in deliberate overdose.[51][45] Epidemiological studies have not found associations between long term low level exposure to glyphosate and any disease.[52][53][54]

Based on an assessment completed in 1993 and published as a Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) document, the EPA considers glyphosate to be noncarcinogenic and relatively low in dermal and oral acute toxicity.[46] The EPA considered a "worst case" dietary risk model of an individual eating a lifetime of food derived entirely from glyphosate-sprayed fields with residues at their maximum levels. This model indicated that no adverse health effects would be expected under such conditions.[46]

In June 2013, the Medical Laboratory in Bremen published a report that glyphosate was present in human urine samples from 18 European countries. Malta showed the highest test results with the chemical showing up in 90% of samples and the average for all countries was 43.9%. Diet was stated as the main source.[55]

Effects on fish and amphibians

Glyphosate is generally less persistent in water than in soil, with 12 to 60 day persistence observed in Canadian pond water, yet because glyphosate binds to soil, persistence of over a year has been observed in the sediments of ponds in Michigan and Oregon.[46] In streams, maximum glyphosate concentrations were measured immediately post-treatment and dissipated rapidly.[46] According to research done in the late 1980s and early 1990 (Ecotoxicological Risk Assessment for Roundup® Herbicide), glyphosate in ecological exposures studied is "practically nontoxic to slightly toxic" for amphibians and fish.[56]

Soil degradation, and effects on micro-organism and worms

When glyphosate comes into contact with the soil, it can be rapidly bound to soil particles and be inactivated.[57][58] Unbound glyphosate can be degraded by bacteria.[59] Glyphosate and its degradation product, aminomethylphosphonate (AMPA), residues are considered to be much more toxicologically and environmentally benign than most of the herbicides replaced by glyphosate.[60]

In soils, half-lives vary from as little as three days at a site in Texas to 141 days at a site in Iowa.[58] In addition, the glyphosate metabolite aminomethylphosphonic acid has been found in Swedish forest soils up to two years after a glyphosate application.[61] Glyphosate adsorption to soil, and later release from soil, varies depending on the kind of soil.[62][63]

It has been suggested that glyphosate can harm the bacterial ecology of soil and cause micronutrient deficiencies in plants,[64] including nitrogen-fixing bacteria.[65] However, a 2012 study found that while Roundup® (glyphosate with adjuvants) had toxic effects at low levels on three microorganisms used in dairy products, "glyphosate at these levels has no significant effect".[66]

Additive toxicity

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2012) |

Glyphosate formulations may contain a number of so-called ‘inert’ ingredients or adjuvants, most of which are not publicly known as in many countries the law does not require that they be revealed. However, some information is available about formulations sold in the US.

Polyethoxylated tallow amine (POEA) is the most well known inert as it is contained in the original Roundup formulation. Registration data in New Zealand showed Roundup contained 18% POEA. POEA is a surfactant that enhances the activity of herbicides such as glyphosate. The role of a surfactant in a herbicide product is to improve wettability of the surface of plants for maximum coverage and aid penetration through the plant surface. A review of the literature provided to the EPA in 1997 found that POEA was more toxic to fish than glyphosate.[67]

Formulation Toxicity

Human

Data from the California Environmental Protection Agency's Pesticide Illness Surveillance Program, which also tracks other agricultural chemicals, shows that glyphosate-related incidents are some of the most common.[68][69] However, incident counts alone do not take into account the number of people exposed and the severity of symptoms associated with each incident.[69] For example, if hospitalization were used as a measure of the severity of incidents, then glyphosate would be considered relatively safe; over a 13-year period in California, none of the 515 reported hospitalizations were attributed to glyphosate.[69]

Deliberate ingestion of Roundup in quantities ranging from 85 to 200 ml has resulted in death within hours of ingestion, although it has also been ingested in quantities as large as 500 ml with only mild or moderate symptoms.[70] There is a reasonable correlation between the amount of Roundup ingested and the likelihood of serious systemic sequelae or death. Ingestion of >85 ml of the concentrated formulation is likely to cause significant toxicity in adults. Corrosive effects – mouth, throat and epigastric pain and dysphagia – are common. Renal and hepatic impairment are also frequent and usually reflect reduced organ perfusion. Respiratory distress, impaired consciousness, pulmonary edema, infiltration on chest x-ray, shock, arrythmias, renal failure requiring haemodialysis, metabolic acidosis, and hyperkalaemia may occur in severe cases. Bradycardia and ventricular arrhythmias often present prior to death.

Dermal exposure to ready-to-use glyphosate formulations can cause irritation, and photo-contact dermatitis has been occasionally reported. These effects are probably due to the preservative Proxel (benzisothiazolin-3-one). Inhalation is a minor route of exposure, but spray mist may cause oral or nasal discomfort, an unpleasant taste in the mouth, or tingling and irritation in the throat. Eye exposure may lead to mild conjunctivitis. Superficial corneal injury is possible if irrigation is delayed or inadequate.[45]

In vitro studies on human cells

A 2000 review concluded that "under present and expected conditions of new use, there is no potential for Roundup herbicide to pose a health risk to humans".[71] A 2002 review by the European Union reached the same conclusion.[72]

Glyphosate causes oxidative damage to human skin cells. Antioxidants such as vitamins C and E were found by one study to provide some protection against such damage, leading the authors to recommend that these chemicals be added to glyphosate formulations.[73] Severe skin burns are very rare.[45]

Endocrine disruption

A study published in 2000 found that Roundup interfered with an enzyme involved in testosterone production in mouse cell culture.[74] A study by the Seralini lab published in 2005 found that glyphosate interferes with aromatase, an estrogen biosynthesis enzyme, in cultures of human placental cells and that the Roundup formulation of glyphosate had stronger such activity.[75] A follow up study by the Seralini lab, published in 2009, showed similar results in human liver cells.[76] A study on rats published in 2010 found that administering Roundup Transorb orally to prepubescent rats at a dose of 0.25 mL/100 g of body weight, once a day for 30 days, reduced testosterone production and affected testicle morphology, but did not affect levels of estradiol and corticosterone.[77]

Monsanto has responded, saying that (a) Roundup formulations do contain surfactants (detergents) to help the active ingredient penetrate the waxy cuticle of the plant. (b) The surfactants are indeed more toxic than the glyphosate. (c) "If you put a detergent of any sort on cells in a petri dish, the cells get sick (and will die if you get the concentration high enough or recover if you remove the detergent soon enough)"; (d) the cell types chosen in these studies and the parameters measured were selected more to score political points than to help fully describe the risks of glyphosate and surfactants; (e) the experiments are artificial and not helpful – no one is supposed to drink Roundup, and it is not ever put on naked cells (we all have skin and workers are meant to wear protective clothes).[78]

In 2007, the EPA selected glyphosate for further screening through its Endocrine Disruptor Screening Program. Selection for this program is based on a compound's prevalence of use and does not imply particular suspicion of endocrine activity.[79]

Genetic damage

Several studies have not found mutagenic effects[80] and therefore glyphosate has not been listed in the U.S. EPA/IARC databases.[81] Various other studies suggest that glyphosate may be mutagenic.[81]

Other mammals

A review of the ecotoxicological data on Roundup shows there are at least 58 studies of the effects of Roundup itself on a range of organisms.[56] This review concluded that "for terrestrial uses of Roundup minimal acute and chronic risk was predicted for potentially exposed non-target organisms".

In a 2001 study, three groups of pregnant rats were fed, respectively, a regular diet with clean water, a regular diet with 0.2 ml glyphosate/ml drinking water; and a regular diet with 0.4 ml glyphosate/ml drinking water. Glyphosate induces a variety of functional abnormalities in fetuses and pregnant rats.[82] Also in recent mammalian research, glyphosate has been found to interfere with an enzyme involved testosterone production in mouse cell culture.[74]

Glyphosate is low in toxicity to rats when ingested by rats. The acute oral LD50 in rats is greater than 4320 mg/kg. Rats and mice were fed a diet containing 0, 3125, 6250, 12,500, 25,000, or 50,000 ppm of 99% pure glyphosate for 13 weeks. The two highest dose groups of male rats had a significant reduction in sperm concentrations, although concentrations were still within the historical range for that rat strain. The highest dose group of female rats had a slightly longer estrus cycle than the control group. The Reference Dose for glyphosate set by the EPA is 1.75 mg/kg/day and the maximum contaminant level set by the EPA is 0.7 mg/L[20][83]

The EPA,[84] the EC Health and Consumer Protection Directorate, and the UN World Health Organization have all concluded pure glyphosate is not carcinogenic. Opponents of glyphosate claim Roundup has been found to cause genetic damage, citing Peluso et al.[85] The authors concluded the damage was "not related to the active ingredient, but to another component of the herbicide mixture".

Mammal research indicates oral intake of 1% glyphosate induces changes in liver enzyme activities in pregnant rats and their fetuses.[82]

Laboratory studies have shown teratogenic effects of Roundup in animals.[86][87] These reports have proposed that the teratogenic effects are caused by impaired retinoic acid signaling.[88] News reports have supposed that regulators have been aware of these studies since 1980.[89]

Effects on fish and amphibians

Glyphosate is generally less persistent in water than in soil, with 12 to 60 day persistence observed in Canadian pond water, yet persistence of over a year have been observed in the sediments of ponds in Michigan and Oregon.[46] However, low glyphosate concentrations can be found in many creeks and rivers in the US and in Europe.[90]

A 2003 study of various formulations of glyphosate found that "risk assessments based on estimated and measured concentrations of glyphosate that would result from its use for the control of undesirable plants in wetlands and over-water situations showed that the risk to aquatic organisms is negligible or small at application rates less than 4 kg/ha and only slightly greater at application rates of 8 kg/ha.".[91] A more recent (2013) meta-analysis also reviewed the available data related to potential impacts of glyphosate-based herbicides on amphibians. According to the authors, because little is known about environmental concentrations of glyphosate in amphibian habitats and virtually nothing is known about environmental concentrations of the substances added to the herbicide formulations, if and how glyphosate-based herbicides contribute to amphibian decline is not yet answerable due to missing data on how natural populations are affected. They concluded that the impact on amphibians depends on the herbicide formulation with different sensitivity of taxa and life stages while effects on development of larvae are seen as the most sensitive endpoints to study. The authors recommend "better monitoring of both amphibian populations and contamination of habitats with glyphosate-based herbicides, not just glyphosate," and suggest including amphibians in standardized test batteries.[92]

Glyphosate formulations are much more toxic for amphibians and fish than glyphosate alone.[56][93][94][95] Glyphosate formulations may contain a number of so-called ‘inert’ ingredients or adjuvants, most of which are not publicly known as in many countries the law does not require that they be revealed.[90]

A study published in 2010 proposed commercial glyphosate can cause neural defects and craniofacial malformations in African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis). The experiments used frog embryos that were incubated with 1:5000 dilutions of a commercial glyphosate solution. The frog embryos suffered diminution of body size, alterations of brain morphology, reduction of the eyes, alterations of the branchial arches and otic placodes, alterations of the neural plate, and other abnormalities of the nervous system. The authors suggested glyphosate itself was responsible for the observed results because injection of pure glyphosate produced similar results in a chicken model.[88]

Monsanto and other companies produce glyphosate products with alternative surfactants that are specifically formulated for aquatic use, for example the Monsanto products "Biactive" and "AquaMaster".[96] [97] In 2001 the Monsanto product Vision® was studied in a forest wetlands site in Canada. Substantial mortality occurred only at concentrations exceeding the expected environmental concentrations as calculated by Canadian regulatory authorities. While it was found that site factors such as pH and suspended sediments substantially affected the toxicity in the amphibian larvae tested, overall, "results suggest that the silvicultural use of Vision herbicide in accordance with the product label and standard Canadian environmental regulations should have negligible adverse effects on sensitive larval life stages of native amphibians."[98]

Effect on plant health

A study published in 2005 found a correlation between an increase in the infection rate of wheat by fusarium head blight and the application of glyphosate, but the authors wrote: "because of the nature of this study, we could not determine if the association between previous GF (glyphosate formulation) use and FHB development was a cause-effect relationship".[99] Other studies have found causal relationships between glyphosate and decreased disease resistance.[100]

Resistance

Resistance evolves after a weed population has been subjected to intense selection pressure in the form of repeated use of a single herbicide.[101][102] Weeds resistant to the herbicide have been called superweeds.[103] The first documented cases of weed resistance to glyphosate were found in Australia in 1996, involving rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum) near Orange, New South Wales.[104][105] In 2006, farmers associations were reporting 103 biotypes of weeds within 63 weed species with herbicide resistance.[106] In 2009, Canada identified its first resistant weed, giant ragweed, and at that time fifteen weed species had been confirmed as resistant to glyphosate.[101][107] As of 2010, in the United States 7 to 10 million acres (40,000 km2) of soil was afflicted by superweeds, or about 5% of the 170 million acres planted with corn, soybeans and cotton, the crops most affected, in 22 states.[108] In 2012, the Weed Science Society of America[109] listed 22 super weeds in the U.S., with over 5.7 million hectares (14 million acres) infested by GR weeds. Dow AgroSciences carried out a recent survey and reported a figure of around 40 million hectares (100 million acres). [110]

A 2012 study refuted the claim that genetically-engineered crops have reduced pesticide use. Looking at the impact of rapidly spreading glyphosate-resistant weeds, their research showed that over the 16 year period since glyphosate herbicides were introduced, herbicide-resistant crop technology has led to a 239 million kilogram (527 million pound) increase in herbicide use in the United States, while Bt crops have reduced insecticide applications by 56 million kilograms (123 million pounds). Overall, pesticide use increased by an estimated 183 million kgs (404 million pounds), or about 7%.[110]

In response to resistant weeds, farmers are hand-weeding, using tractors to turn over soil between crops, and using other herbicides in addition to glyphosate. Agricultural biotech companies are also developing genetically engineered crops resistant to other herbicides. "Bayer is already selling cotton and soybeans resistant to glufosinate, another weedkiller. Monsanto's newest corn is tolerant of both glyphosate and glufosinate, and the company is developing crops resistant to dicamba, an older pesticide. Syngenta is developing soybeans tolerant of its Callisto product. And Dow Chemical is developing corn and soybeans resistant to 2,4-D, a component of Agent Orange, the defoliant used in the Vietnam War."[108]

Palmer amaranth

In 2004, a glyphosate-resistant variation of Palmer amaranth, commonly known as pigweed, was found in Georgia and confirmed by a 2005 study.[111] In 2005, resistance was also found in North Carolina.[112] Widespread use of Roundup Ready crops led to an unprecedented selection pressure and glyphosate resistance followed.[112] The weed variation is now widespread in the southeastern United States.[113] Cases have also been reported in Texas[113] and Virginia.[114]

Conyza

Conyza bonariensis (also known as hairy fleabane and buva) and Conyza canadensis (known as horseweed or marestail), are other weed species that had lately developed glyphosate resistance.[115][116][117] A 2008 study on the current situation of glyphosate resistance in South America concluded that "resistance evolution followed intense glyphosate use" and the utilization of glyphosate-resistant soybean crops is a factor encouraging increase in glyphosate use.[118]

Ryegrass

Glyphosate resistant ryegrass (Lolium) has occurred in most of the Australian agricultural area and other areas of the world. All cases of evolution of resistance to glyphosate in Australia were characterized by intensive use of the herbicide while no other effective weed control practices were used. Studies indicate that resistant ryegrass does not compete well against non-resistant plants and their numbers decrease when not grown under conditions of glyphosate application.[119]

Johnson grass

Glyphosate-resistant Johnson grass (Sorghum halepense) has occurred in glyphosate-resistant soybean culture in Argentina.[120]

Coca

Boliviana negra, also known as "supercoca", is a relatively new strain of coca that is resistant to glyphosate, which is a key ingredient in the multibillion-dollar aerial coca eradication campaign undertaken by the government of Colombia with United States financial and military backing known as Plan Colombia.[121] Spraying Boliviana negra with glyphosate would serve to strengthen its growth by eliminating the non-resistant weeds surrounding it. Joshua Davis, writing in Wired magazine, found no evidence of CP4 EPSPS, a protein produced by the Roundup Ready soybean, suggesting Bolivana negra was not created in a laboratory but by selective breeding in the fields. According to Davis, the growing popularity of Boliviana negra amongst growers could have serious repercussions for the United States war on drugs.[122][123]

Legal cases

False advertising

The New York Times reported that in 1996, "Dennis C. Vacco, the Attorney General of New York, ordered the company to pull ads that said Roundup was "safer than table salt" and "practically nontoxic" to mammals, birds and fish. The company withdrew the spots, but also said that the phrase in question was permissible under E.P.A. guidelines."[124]

On Fri Jan 20, 2007, Monsanto was convicted in France of false advertising of Roundup for presenting it as biodegradable, and claiming it left the soil clean after use. Environmental and consumer rights campaigners brought the case in 2001 on the basis that glyphosate, Roundup's main ingredient, is classed as "dangerous for the environment" and "toxic for aquatic organisms" by the European Union.[125] Monsanto appealed and the court upheld the verdict; Monsanto appealed again to the French Supreme Court, and in 2009 it also upheld the verdict.[126]

Scientific fraud

On two occasions, the United States EPA has caught scientists deliberately falsifying test results at research laboratories hired by Monsanto to study glyphosate.[127] The first incident involved Industrial Biotest Laboratories (IBT). The United States Justice Department closed the laboratory in 1978, and its leadership was found guilty in 1983 of charges of falsifying statements, falsifying scientific data submitted to the government, and mail fraud.[128] In 1991, Don Craven, the owner of Craven Laboratories and three employees were indicted on 20 felony counts. Craven, along with fourteen employees were found guilty of similar crimes.[129]

Monsanto has stated the Craven Labs investigation was started by the EPA after a pesticide industry task force discovered irregularities, that the studies have been repeated, and that Roundup's EPA certification does not now use any studies from Craven Labs or IBT.[127]

Trade dumping allegations

United States companies have cited trade issues with glyphosate being dumped into the western world market areas by Chinese companies and a formal dispute was filed in 2010.[130][131]

Genetically modified crops

Some micro-organisms have a version of 5-enolpyruvoyl-shikimate-3-phosphate synthetase (EPSPS) that is resistant to glyphosate inhibition. The version used in the initial round of genetically modified crops was isolated from Agrobacterium strain CP4 (CP4 EPSPS) that was resistant to glyphosate.[132][15] This CP4 EPSPS gene was cloned and transfected into soybeans. In 1996, genetically modified soybeans were made commercially available.[133] Current glyphosate-resistant crops include soy, maize (corn), sorghum, canola, alfalfa, and cotton, with wheat still under development.

Genetically modified crops have become the norm in the United States. For example, in 2010, 70% of all the corn that was planted was herbicide-resistant; 78% of cotton, and 93% of all soybeans.[134]

See also

- Environmental impact of pesticides

- Health effects of pesticides

- 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid

- Atrazine

- Integrated pest management

References

- ^ a b Glyphosate, Environmental Health Criteria monograph No. 159, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1994, ISBN 92-4-157159-4

- ^ Index no. 607-315-00-8 of Annex VI, Part 3, to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on classification, labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures, amending and repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006. OJEU L353, 31.12.2008, pp 1–1355 at pp 570, 1100..

- ^ US patent 3799758, Franz JE, "N-phosphonomethyl-glycine phytotoxicant compositions", issued 1974-03-26, assigned to Monsanto Company

- ^ United States EPA 2007 Pesticide Market Estimates Agriculture, Home and Garden

- ^ Graves L (24 June 2011). "Roundup: Birth Defects Caused By World's Top-Selling Weedkiller, Scientists Say". Huffington Post.

- ^ Alibhai MF, Stallings WC (2001). "Closing down on glyphosate inhibition--with a new structure for drug discovery". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (6): 2944–6. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.2944A. doi:10.1073/pnas.061025898. JSTOR 3055165. PMC 33334. PMID 11248008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "The National Medal of Technology and Innovation Recipients - 1987". The United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved 2012-011-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Stong C (1990). "People: Monsanto Scientist John E. Franz Wins 1990 Perkin Medal For Applied Chemistry". The Scientist. 4 (10): 28.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Meet the 2007 National Inventors Hall of Fame Inductees". National Inventors Hall of Fame. 2007.

- ^ Schuette J. "Environmental Fate of Glyphosate" (PDF). Department of Pesticide Regulation, State of California.

- ^ Steinrücken HC, Amrhein N (1980). "The herbicide glyphosate is a potent inhibitor of 5-enolpyruvyl-shikimic acid-3-phosphate synthase". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 94 (4): 1207–12. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(80)90547-1. PMID 7396959.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Purdue University, Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Metabolic Plant Physiology Lecture notes, Aromatic amino acid biosynthesis, The shikimate pathway – synthesis of chorismate.[1]

- ^ Schönbrunn E, Eschenburg S, Shuttleworth WA, Schloss JV, Amrhein N, Evans JN, Kabsch W (2001). "Interaction of the herbicide glyphosate with its target enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase in atomic detail". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (4): 1376–80. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.1376S. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.4.1376. PMC 29264. PMID 11171958.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Glyphosate bound to proteins in the Protein Data Bank

- ^ a b Funke T, Han H, Healy-Fried ML, Fischer M, Schönbrunn E (2006). "Molecular basis for the herbicide resistance of Roundup Ready crops". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (35): 13010–5. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10313010. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603638103. JSTOR 30050705. PMC 1559744. PMID 16916934.

{{cite journal}}: Check|bibcode=length (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Su LY, Dela Cruz A, Moor PH, Maretzki PH (1992). "The Relationship of Glyphosate Treatment to Sugar Metabolism in Sugarcane: New Physiological Insights". Journal of Plant Physiology. 140 (2): 168. doi:10.1016/S0176-1617(11)80929-6.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lamb DC, Kelly DE, Hanley SZ, Mehmood Z, Kelly SL (1998). "Glyphosate is an inhibitor of plant cytochrome P450: functional expression of Thlaspi arvensae cytochrome P45071B1/reductase fusion protein in Escherichia coli". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 244 (1): 110–4. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.7988. PMID 9514851.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hietanen E, Linnainmaa K, Vainio H (1983). "Effects of phenoxyherbicides and glyphosate on the hepatic and intestinal biotransformation activities in the rat". Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh). 53 (2): 103–12. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1983.tb01876.x. PMID 6624478.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Integrated Pest Management

- ^ a b c National Pesticide Information Center Technical Factsheet on: GLYPHOSATE

- ^ Thomas M Amrein (12/21/2012). "Analysis of pesticides in food" (PDF). ETH Zurich. p. 15. Retrieved 06/02/2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b "The agronomic benefits of glyphosate in Europe" (PDF). Monsanto Europe SA. February 2010. Retrieved 06/02/2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Measures to reduce glyphosate runoff from hard surfaces

- ^ Botta F, Lavison G, Couturier G, Alliot F, Moreau-Guigon E, Fauchon N, Guery B, Chevreuil M, Blanchoud H (2009). "Transfer of glyphosate and its degradate AMPA to surface waters through urban sewerage systems". Chemosphere. 77 (1): 133–9. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.05.008. PMID 19482331.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Plan Colombia

- ^ Jeremy McDermott. The Scotsman (Scotland) 27 August 2004 New Super Strain of Coca Plant Stuns Anti-Drug Officials

- ^ Chris Kraul for the Los Angeles Times. February 25, 2008 Picture a natural disaster wrought by drug trade

- ^ Mitchem W. "Mirror or Mirror on the Wall Show Me the Best Glyphosate Formulation of All" (PDF). North Carolina State University Extension. Retrieved 2013-07-23.

- ^ Hartzler B. "ISU Weed Science Online - Glyphosate - A Review". Iowa State University Extension.

- ^ a b Tu M, Hurd C, Robison R, Randall JM (2001-11-01). "Glyphosate" (PDF). Weed Control Methods Handbook. The Nature Conservancy.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b VanGessel M. "Glyphosate Formulations". Control Methods Handbook, Chapter 8, Adjuvants: Weekly Crop Update. University of Delaware Cooperative Extension.

- ^ Tu M, Randall JM (2003-06-01). "Glyphosate" (PDF). Weed Control Methods Handbook. The Nature Conservancy.

- ^ Curran WS, McGlamery MD, Liebl RA, Lingenfelter DD (1999). "Adjuvants for Enhancing Herbicide Performance". Penn State Extension.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sprague C, Hager A (2000-05-12). "Principles of Postemergence Herbicides". University of Illinois Extension Service. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ^ Young B. "Adjuvant Products by Manufacturer, Compendium of Herbicide Adjuvants". Southern Illinois University.

- ^ e-phy: Le catalogue des produits phytopharmaceutiques et de leurs usages des matières fertilisantes et des supports de culture homologués en France

- ^ "The debate over whether Monsanto is a corporate sinner or saint". The Economist. 19 November 2009. Retrieved 20 November 2009.

- ^ Cavallaro M (2009-06-26). "The Seeds Of A Monsanto Short Play". Forbes. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ^ Altieri MA (2009). "The Ecological Impacts of Large-Scale Agrofuel Monoculture Production Systems in the Americas". Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. 29 (3): 236. doi:10.1177/0270467609333728.

- ^ Benachour N, Séralini GE (2009). "Glyphosate formulations induce apoptosis and necrosis in human umbilical, embryonic, and placental cells". Chem. Res. Toxicol. 22 (1): 97–105. doi:10.1021/tx800218n. PMID 19105591.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hedberg D, Wallin M (2010). "Effects of Roundup and glyphosate formulations on intracellular transport, microtubules and actin filaments in Xenopus laevis melanophores". Toxicol in Vitro. 24 (3): 795–802. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2009.12.020. PMID 20036731.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zeliger HI (2008). Human Toxicology of Chemical Mixtures. William Andrew. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-8155-1589-0.

- ^ "Round up: une association veut le retrait". Le Figaro (in French). 2009-11-18. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ "Dossier de presse – alerte pesticides: le cas de 3 Roundup" (PDF) (in French). Mouvement pour les droits et le respect des générations futures (MDRGF). 2009-11-01. Retrieved November 2009-11-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c d Bradberry SM, Proudfoot AT, Vale JA (2004). "Glyphosate poisoning". Toxicol Rev. 23 (3): 159–67. doi:10.2165/00139709-200423030-00003. PMID 15862083.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g "Registration Decision Fact Sheet for Glyphosate (EPA-738-F-93-011)" (PDF). R.E.D. FACTS. United States Environmental Protection Agency. 1993.

- ^ "Sample label – Roundup Pro" (PDF). Armed Forces Pest Management Board.

- ^ Williams G, Kroes R, Munro I (2005-05-01). "Summary of Human Risk Assessment and Safety Evaluation on Glyphosate and Roundup Herbicide" (PDF). Backgrounder. Monsanto Company.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sheng M, Hamel C, Fernandez MR (2012). "Cropping practices modulate the impact of glyphosate on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and rhizosphere bacteria in agroecosystems of the semiarid prairie". Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 58 (8): 990–1001. doi:10.1139/w2012-080. PMID 22827807.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Helander M, Saloniemi I, Saikkonen K (2012). "Glyphosate in northern ecosystems". Trends in Plant Science. 17 (10): 569–574. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2012.05.008. PMID 22677798.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sribanditmongkol P, Jutavijittum P, Pongraveevongsa P, Wunnapuk K, Durongkadech P (2012). "Pathological and toxicological findings in glyphosate-surfactant herbicide fatality: a case report". Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 33 (3): 234–7. doi:10.1097/PAF.0b013e31824b936c. PMID 22835958.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mink PJ, Mandel JS, Lundin JI, Sceurman BK (2011). "Epidemiologic studies of glyphosate and non-cancer health outcomes: a review". Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 61 (2): 172–84. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2011.07.006. PMID 21798302.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mink PJ, Mandel JS, Sceurman BK, Lundin JI (2012). "Epidemiologic studies of glyphosate and cancer: a review". Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 63 (3): 440–52. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2012.05.012. PMID 22683395.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Williams AL, Watson RE, DeSesso JM (2012). "Developmental and reproductive outcomes in humans and animals after glyphosate exposure: a critical analysis". J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 15 (1): 39–96. doi:10.1080/10937404.2012.632361. PMID 22202229.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Determination of Glyphosate residues in human urine samples from 18 European countries" (PDF). Medizinisches Labor Bremen. 2013.

- ^ a b c d Giesy JP, Dobson S, Solomon KR (2000). "Ecotoxicological Risk Assessment for Roundup® Herbicide". Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 167: 35–120. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-1156-3_2. ISBN 978-0-387-95102-7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ United States EPA Reregistration Eligibility Decision – Glyphosate – (EPA-738-F-93-011) 1993 [2]

- ^ a b Andréa MM, Peres TB, Luchini LC, Bazarin S, Papini S, Matallo MB, Savoy VLT (2003). "Influence of repeated applications of glyphosate on its persistence and soil bioactivity". Pesquisa Agropecuária Brasileira. 38 (11): 1329. doi:10.1590/S0100-204X2003001100012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Balthazor TM, Hallas LE (1986). "Glyphosate-degrading microorganisms from industrial activated sludge". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51 (2): 432–4. PMC 238888. PMID 16346999.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cerdeira AL, Duke SO (2010). "Effects of glyphosate-resistant crop cultivation on soil and water quality". GM Crops. 1 (1): 16–24. doi:10.4161/gmcr.1.1.9404. PMID 21912208.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Torstensson NT, Lundgren LN, Stenström J (1989). "Influence of climatic and edaphic factors on persistence of glyphosate and 2,4-D in forest soils". Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 18 (2): 230–9. doi:10.1016/0147-6513(89)90084-5. PMID 2806176.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Albers CN, Banta GT, Hansen PE, Jacobsen OS (2009). "The influence of organic matter on sorption and fate of glyphosate in soil--comparing different soils and humic substances". Environ. Pollut. 157 (10): 2865–70. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2009.04.004. PMID 19447533.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ole K. Borggaard OK (2011). "Does phosphate affect soil sorption and degradation of glyphosate? - A review". Trends in Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 2 (1): 17–27.

- ^ Dick R, Lorenz N, Wojno M, Lane M (2010). Microbial dynamics in soils under long-term glyphosate tolerant cropping systems (PDF). 19th World Congress of Soil Science.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Santos A, Flores M (1995). "Effects of glyphosate on nitrogen fixation of free-living heterotrophic bacteria". Letters in Applied Microbiology. 20 (6): 349–52. doi:10.1111/j.1472-765X.1995.tb01318.x.

- ^ Clair E, Linn L, Travert C, Amiel C, Séralini GE, Panoff JM (2012). "Effects of Roundup(®) and glyphosate on three food microorganisms: Geotrichum candidum, Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus". Curr. Microbiol. 64 (5): 486–91. doi:10.1007/s00284-012-0098-3. PMID 22362186.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gary L. Diamond and Patrick R. Durkin February 6, 1997, under contract from the United States Department of Agriculture. Effects of Surfactants on the Toxicitiy of Glyphosate, with Specific Reference to RODEO

- ^ Goldstein DA, Acquavella JF, Mannion RM, Farmer DR (2002). "An analysis of glyphosate data from the California Environmental Protection Agency Pesticide Illness Surveillance Program". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 40 (7): 885–92. doi:10.1081/CLT-120016960. PMID 12507058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Pesticide Illness Surveillance Program". California Pesticide Illness Serveillance Program Report HS-1733. California EPA. 2010.

- ^ Talbot AR, Shiaw MH, Huang JS, Yang SF, Goo TS, Wang SH, Chen CL, Sanford TR (1991). "Acute poisoning with a glyphosate-surfactant herbicide ('Roundup'): a review of 93 cases". Hum Exp Toxicol. 10 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1177/096032719101000101. PMID 1673618.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Williams GM, Kroes R, Munro IC (2000). "Safety evaluation and risk assessment of the herbicide Roundup and its active ingredient, glyphosate, for humans". Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 31 (2 Pt 1): 117–65. doi:10.1006/rtph.1999.1371. PMID 10854122.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Review report for the active substance glyphosate" (PDF). Commission working document. European Commission, Health and Protection Directorate-General: Directorate E – Food Safety: plant health, animal health and welfare, international questions: E1 - Plant Health. 2002-01-21.

- ^ Gehin A, Guillaume YC, Millet J, Guyon C, Nicod L (2005). "Vitamins C and E reverse effect of herbicide-induced toxicity on human epidermal cells HaCaT: a biochemometric approach". Int J Pharm. 288 (2): 219–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.09.024. PMID 15620861.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Walsh LP, McCormick C, Martin C, Stocco DM (2000). "Roundup inhibits steroidogenesis by disrupting steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein expression". Environ. Health Perspect. 108 (8): 769–76. doi:10.1289/ehp.00108769. PMC 1638308. PMID 10964798.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Richard S, Moslemi S, Sipahutar H, Benachour N, Seralini GE (2005). "Differential effects of glyphosate and roundup on human placental cells and aromatase". Environ. Health Perspect. 113 (6): 716–20. doi:10.1289/ehp.7728. PMC 1257596. PMID 15929894.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gasnier C, Dumont C, Benachour N, Clair E, Chagnon MC, Séralini GE (2009). "Glyphosate-based herbicides are toxic and endocrine disruptors in human cell lines". Toxicology. 262 (3): 184–91. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2009.06.006. PMID 19539684.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Romano RM, Romano MA, Bernardi MM, Furtado PV, Oliveira CA (2010). "Prepubertal exposure to commercial formulation of the herbicide glyphosate alters testosterone levels and testicular morphology". Arch. Toxicol. 84 (4): 309–17. doi:10.1007/s00204-009-0494-z. PMID 20012598.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Monsantoblog: The Skinny on the Seralini Safety Study 2009/06/23

- ^ EPA Federal Register http://www.epa.gov/endo/pubs/draft_list_frn_061807.pdf

- ^ ToxNet. Glyposate. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b András Székács and Béla Darvas. Forty years with glyphosate. In: Herbicides - Properties, Synthesis and Control of Weeds", Ed. Mohammed Naguib Abd El-Ghany Hasaneen, ISBN 978-953-307-803-8, Published: January 13, 2012.

- ^ a b Daruich J, Zirulnik F, Gimenez MS (2001). "Effect of the herbicide glyphosate on enzymatic activity in pregnant rats and their fetuses". Environ. Res. 85 (3): 226–31. Bibcode:2001ER.....85..226D. doi:10.1006/enrs.2000.4229. PMID 11237511.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Roundup PRO Herbicide" (PDF). MSDS. Monsanto Company.

- ^ United States EPA Reregistration Eligibility Decision – Glyphosate

- ^ Peluso M, Munnia A, Bolognesi C, Parodi S (1998). "32P-postlabeling detection of DNA adducts in mice treated with the herbicide Roundup". Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 31 (1): 55–9. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2280(1998)31:1<55::AID-EM8>3.0.CO;2-A. PMID 9464316.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lammer EJ, Chen DT, Hoar RM, Agnish ND, Benke PJ, Braun JT, Curry CJ, Fernhoff PM, Grix AW, Lott IT (1985). "Retinoic acid embryopathy". N. Engl. J. Med. 313 (14): 837–41. doi:10.1056/NEJM198510033131401. PMID 3162101.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Durston AJ, Timmermans JP, Hage WJ, Hendriks HF, de Vries NJ, Heideveld M, Nieuwkoop PD (1989). "Retinoic acid causes an anteroposterior transformation in the developing central nervous system". Nature. 340 (6229): 140–4. Bibcode:1989Natur.340..140D. doi:10.1038/340140a0. PMID 2739735.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Paganelli A, Gnazzo V, Acosta H, López SL, Carrasco AE (2010). "Glyphosate-based herbicides produce teratogenic effects on vertebrates by impairing retinoic acid signaling". Chem. Res. Toxicol. 23 (10): 1586–95. doi:10.1021/tx1001749. PMID 20695457.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Graves L (7 June 2011). "Roundup Birth Defects: Regulators Knew World's Best-Selling Herbicide Causes Problems, New Report Finds". Huffington Post. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ a b http://www.panap.net/sites/default/files/monograph_glyphosate.pdf

- ^ Solomon KR, Thompson DG (2003). "Ecological risk assessment for aquatic organisms from over-water uses of glyphosate". J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 6 (3): 289–324. doi:10.1080/10937400306468. PMID 12746143.

- ^ Questions concerning the potential impa... [Environ Toxicol Chem. 2013] - PubMed - NCBI

- ^ Salbego J, Pretto A, Gioda CR, de Menezes CC, Lazzari R, Radünz Neto J, Baldisserotto B, Loro VL (2010). "Herbicide formulation with glyphosate affects growth, acetylcholinesterase activity, and metabolic and hematological parameters in piava (Leporinus obtusidens)". Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 58 (3): 740–5. doi:10.1007/s00244-009-9464-y. PMID 20112104.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Relyea RA (2005). "The impact of insecticides and herbicides on the biodiversity and productivity of aquatic communities". Ecol Appl. 15 (2): 618–27. doi:10.1890/03-5342. JSTOR 4543379. PMID 17069392.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Thompson DG, Solomon KR, Wojtaszek BF, Edginton AN, Stephenson GR (2006). "The impact of insecticides and herbicides on the biodiversity and productivity of aquatic communities". Ecol Appl. 16 (5): 2022–7, author reply 2027–34. doi:10.1890/03-5342. PMID 17069392.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Response to "The impact of insecticides and herbicides on the biodiversity and productivity of aquatic communities"" (PDF). Backgrounder. Monsanto Company. 2005-04-01.

- ^ "Aquatic Use of Glyphosate Herbicides in Australia" (PDF). Backgrounder. Monsanto Company. 2003-05-01.

- ^ Wojtaszek BF, Staznik B, Chartrand DT, Stephenson GR, Thompson DG (2004). "Effects of Vision® herbicide on mortality, avoidance response, and growth of amphibian larvae in two forest wetlands". Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 23 (4): 832–42. doi:10.1897/02-281. PMID 15095877.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fernandez MR, Selles F, Gehl D, Depauw RM, Zentner RP (2005). "Crop Production Factors Associated with Fusarium Head Blight in Spring Wheat in Eastern Saskatchewan". Crop Science. 45 (5): 1908–16. doi:10.2135/cropsci2004.0197.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Duke SO, Wedge DE, Cerdeira AL, Matallo MB (2007). "Interactions of Synthetic Herbicides with Plant Disease and Microbial Herbicides". In Vurro, Maurizio; Gressel, Jonathan (eds.). Novel Biotechnologies for Biocontrol Agent Enhancement and Management. NATO Security through Science Series. pp. 277–96. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-5799-1_15. ISBN 978-1-4020-5797-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lori (2009-05-07). "U of G Researchers Find Suspected Glyphosate-Resistant Weed". Uoguelph.ca. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "Resisting Roundup". The New York Times. 2010-05-16.

- ^ Tarter S (2009-04-06). "PJStar.com". PJStar.com. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ ISU Weed Science Online – Are RR Weeds in Your Future I

- ^ Powles SB, Lorraine-Colwill DF, Dellow JJ, Preston C (1998). "Evolved Resistance to Glyphosate in Rigid Ryegrass (Lolium rigidum) in Australia". Weed Science. 46 (5): 604–7. JSTOR 4045968.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Glyphosate resistance is a reality that should scare some cotton growers into changing the way they do business". Southeastfarmpress.com. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "Map of Glyphosate-Resistant Weeds Globally". The International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds. 2010. Retrieved 12 Jan 2013.

- ^ a b Neuman W, Pollack A (4 May 2010). "U.S. Farmers Cope With Roundup-Resistant Weeds". New York Times. New York. pp. B1. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Weed Science Society of America

- ^ a b Environmental Sciences Europe | Full text | Impacts of genetically engineered crops on pesticide use in the U.S. - the first sixteen years

- ^ Culpepper AS, Grey TL, Vencill WK, Kichler JM, Webster TM, Brown SM, York AC Davis JW, Hanna WW (2006). "Glyphosate-resistant Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri ) confirmed in Georgia". Weed Science. 54 (4): 620–6. doi:10.1614/WS-06-001R.1. JSTOR 4539441.

{{cite journal}}: hair space character in|title=at position 57 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hampton N. "Cotton versus the monster weed". Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ a b Smith JT (March 2009). "Resistance a growing problem" (PDF). The Farmer Stockman. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ Taylor O (2009-07-16). "Peanuts: variable insects, variable weather, Roundup resistant Palmer in new state". PeanutFax. AgFax Media. Retrieved 2009-07-19.

- ^ Vargas L, Bianchi MA, Rizzardi MA, Agostinetto D, Dal Magro T (2007). "Buva (Conyza bonariensis) resistente ao glyphosate na região sul do Brasil". Planta Daninha (in Portuguese). 25 (3): 573–8. doi:10.1590/S0100-83582007000300017.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Koger CH, Shaner DL, Henry WB, Nadler-Hassar T, Thomas WE, Wilcut JW (2005). "Assessment of two nondestructive assays for detecting glyphosate resistance in horseweed (Conyza canadensis)". Weed Science. 53 (4): 438–45. doi:10.1614/WS-05-010R. JSTOR 4047050.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ge X, d'Avignon DA, Ackerman JJ, Sammons RD (2010). "Rapid vacuolar sequestration: the horseweed glyphosate resistance mechanism". Pest Manag. Sci. 66 (4): 345–8. doi:10.1002/ps.1911. PMC 3080097. PMID 20063320.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vila-Aiub MM, Vidal RA, Balbi MC, Gundel PE, Trucco F, Ghersa CM (2008). "Glyphosate-resistant weeds of South American cropping systems: an overview". Pest Manag. Sci. 64 (4): 366–71. doi:10.1002/ps.1488. PMID 18161884.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Preston C, Wakelin AM, Dolman FC, Bostamam Y, Boutsalis P (2009). "A Decade of Glyphosate-Resistant Lolium around the World: Mechanisms, Genes, Fitness, and Agronomic Management". Weed Science. 57 (4): 435–41. doi:10.1614/WS-08-181.1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vila-Aiub MM, Balbi MC, Gundel PE, Ghersa CM, Powles SB (2007). "Evolution of Glyphosate-Resistant Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense) in Glyphosate-Resistant Soybean". Weed Science. 55 (6): 566–71. doi:10.1614/WS-07-053.1. JSTOR 4539618.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Helping Colombia Fix Its Plan to Curb Drug Trafficking, Violence, and Insurgency". The Heritage Foundation. April 26, 2001. Retrieved April 26, 2006.

- ^ Davis J (November 2004). "The Mystery of the Coca Plant That Wouldn't Die". Wired.

- ^ "BOLIVIANA NEGRA, LA COCA QUE NO MUERE". El valor de soportar una dura crisis económica. Comunidad Boliviana en la Argentina. 2004-11-14.

- ^ Charry T (1997-05-29). "Monsanto recruits the horticulturist of the San Diego Zoo to pitch its popular herbicide". Business Day. New York Times.

- ^ "Monsanto Fined in France for 'False' Herbicide Ads". Agence France Presse,. Organic Consumers Association. 2007-01-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Monsanto guilty in 'false ad' row". BBC News. 2009-10-15.

- ^ a b "Testing Fraud: IBT and Craven Labs" (PDF). Backgrounder. Monsanto Company. June 2005.

- ^ Schneider K (1983). "Faking it The Case against Industrial Bio-Test Laboratories". The Amicus Journal. PlanetWaves.net: 14–26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "EPA FY1994 Enforcement and Compliance Assurance Accomplishments Report" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency.

- ^ Piller D (2010-04-01). "Albaugh accuses Chinese of dumping herbicide". Staff Blogs. Des Moines Register.

- ^ "In the Matter of: GLYPHOSATE FROM CHINA" (PDF). United States International Trade Commission. 2010-04-22.

- ^ Heck GR, Armstrong CL, Astwood JD, Behr CF, Bookout JT, Brown SM, Cavato TA, Deboer DL, Deng MY (2005). "Development and Characterization of a CP4 EPSPS-Based, Glyphosate-Tolerant Corn Event". Crop Science. 45: 329–39. doi:10.2135/cropsci2005.0329.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Company History". Web Site. Monsanto Company.

- ^ Hamer H (2010-06-30). "Acreage" (PDF). National Agricultural Statistics Board Annual Report,. United States Department of Agriculture.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)