Heraldry

Heraldry in its most general sense encompasses all matters relating to the duties and responsibilities of officers of arms.[1] To most, though, heraldry is the practice of designing, displaying, describing, and recording coats of arms and badges. Historically, it has been variously described as "the shorthand of history"[2] and "the floral border in the garden of history."[3] The origins of heraldry lie in the need to distinguish participants in combat when their faces were hidden by iron and steel helmets.[4] Eventually a system of rules developed into the modern form of heraldry.

The system of blazoning arms that is used today was developed by the officers of arms since the dawn of the art. This includes a description of the escutcheon (shield), the crest, and, if present, supporters, mottoes, and other insignia. An understanding of these rules is one of the keys to sound practice of heraldry. The rules do differ from country to country, but there are some aspects that carry over in each jurisdiction.

Though heraldry is nearly 900 years old, it is still very much in use. Many cities and towns in Europe and around the world still make use of arms. Personal heraldry, both legally protected and lawfully assumed, has continued to be used around the world. Heraldic societies strive to promote education and understanding about the subject.

Origins and history

As early as predynastic Egypt, an emblem known as a serekh was used to indicate the extent of influence of a particular regime, sometimes carved on ivory labels attached to trade goods, but also used to identify military allegiances and in a variety of other ways, even leading to the development of the earliest hieroglyphs. This practice seems to have grown out of the former use of animal mascots literally affixed to staves or standards, as depicted on the earliest cosmetic palettes of the period. Some of the oldest serekhs consist of a striped or cross-hatched box, representing a palace or city, with a crane, scorpion, or other animal drawn standing on top. Before long, the Horus-falcon became the norm as the animal on top, with the individual Pharaoh's symbol usually appearing in the box beneath the falcon, and above the stripes representing the palace.

Ancient warriors often decorated their shields with patterns and mythological motifs. These symbols could be used to identify the warriors bearing them when their faces were obscured by helmets. Army units of the Roman Empire were identified by the distinctive markings on their shields, although these were not heraldic in the medieval and modern sense, as they were associated with units, not individuals or families.[5]

At the time of the Norman conquest of England, heraldry in its essential sense of an inheritable emblem had not yet been developed. The knights in the Bayeux Tapestry carry shields, but there appears to have been no system of hereditary coats of arms. The seeds of heraldic structure in personal identification can be detected in the account in a contemporary chronicle of Henry I of England, on the occasion of his knighting his son-in-law Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, in 1127, placing around his neck a shield painted with golden lions; the funerary enamel of Geoffrey (died 1151), dressed in blue and gold and bearing his azure shield emblazoned with lions rampant or is the first recorded depiction of a coat-of-arms.[6]

By the middle of the 12th century.[7], coats of arms were being inherited by the children of armigers (persons entitled to use a coat of arms) across Europe. Between 1135 and 1155, seals representing the generalized figure of the owner attest to the general adoption of heraldic devices in England, France, Germany, Spain, and Italy.[8] and by the end of the century heraldry appears as the sole device on seals.[9] In England the practice of using marks of cadency arose to distinguish one son from another, and was institutionalized and standardized by John Writhe in the early 15th century.

In the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, heraldry became a highly developed discipline, regulated by professional officers of arms. As its use in jousting became obsolete, coats of arms remained popular for visually identifying a person in other ways—impressed in sealing wax on documents, carved on family tombs, and flown as a banner on country homes. The first work of heraldic jurisprudence, De Insigniis et Armiis, was written in the 1350s by Bartolus de Saxoferrato, a professor of law at the University of Padua.[10]

From the beginning of heraldry, coats of arms have been executed in a wide variety of media, including on paper, painted wood, embroidery, enamel, stonework and stained glass. For the purpose of quick identification in all of these, heraldry distinguishes only seven basic colors[11] and makes no fine distinctions in the precise size or placement of charges on the field.[12] Coats of arms and their accessories are described in a concise jargon called blazon.[13] This technical description of a coat of arms is the standard that must be adhered to no matter what artistic interpretations may be made in a particular depiction of the arms.

The idea that each element of a coat of arms has some specific meaning is unfounded. Though the original armiger may have placed particular meaning on a charge, these meanings are not necessarily retained from generation to generation. Unless "canting arms" incorporate an obvious pun on the bearer's name, it is difficult to find meaning in them.

Changes in military technology and tactics made plate armour obsolete, and heraldry became detached from its original function. This brought about the development of "paper heraldry" under the Tudors, that only existed in paintings. Designs and shields became more elaborate at the expense of clarity. The 20th century's taste for stark iconic emblems made the simple styles of early heraldry fashionable again.

The rules of heraldry

Shield and lozenge

The focus of modern heraldry is the armorial achievement, or the coat of arms, the central element of which is the escutcheon[14] or shield. In general, the shape of the shield employed in a coat of arms is irrelevant, because the fashion for the shield-shapes employed in heraldic art has evolved through the centuries, of course, there are occasions when a blazon specifies a particular shape of shield. These specifications mostly occur in non-European contexts, such as the coat of arms of Nunavut[15] and the former Republic of Bophuthatswana,[16] with North Dakota providing an even more unusual example,[17] while the State of Connecticut specifies a "rococo" shield.[18]—mostly in a non-European context, but not completely, as the Scottish Public Register records an escutcheon of oval form for the Lanarkshire Master Plumbers' and Domestic Engineers' (Employers') Association, and a shield of square form for the Anglo Leasing organisation.

Traditionally, as women did not go to war, they did not bear a shield, instead, women's coats of arms were shown on a lozenge—a rhombus standing on one of its acute corners. This continues true in much of the world, though some heraldic authorities, such as Scotland's, with its ovals for women's arms, make exceptions.[19] In Canada, the restriction against women bearing arms on a shield was eliminated. Non-combatant clergy also have used the lozenge and the cartouche – an oval – for their display.

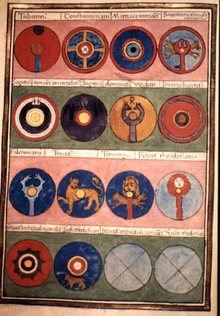

Tinctures

Tinctures are the colors used in heraldry, though a number of patterns called "furs" and the depiction of charges in their natural colors or "proper" are also regarded as tinctures, the latter distinct from any color such a depiction might approximate. Since heraldry is essentially a system of identification, the most important convention of heraldry is the rule of tincture. To provide for contrast and visibility, metals (generally lighter tinctures) must never be placed on metals, and colors (generally darker tinctures) must never be placed on colors. Where a charge overlays a partition of the field, the rule does not apply. There are other exceptions - the most famous being the gold crosses on white chosen as the arms of Godfrey of Bouillon when he was made King of Jerusalem.[20]

The names used in English blazon for the colors and metals come mainly from French and include Or (gold), Argent (white), Azure (blue), Gules (red), Sable (black), Vert (green), and Purpure (purple). A number of other colors are occasionally found, typically for special purposes.[21]

Certain patterns called "furs" can appear in a coat of arms, though they are (rather arbitrarily) defined as tinctures, not patterns. The two common furs are ermine and vair. Ermine represents the winter coat of the stoat, which is white with a black tail. Vair represents a kind of squirrel with a blue-gray back and white belly. Sewn together, it forms a pattern of alternating blue and white shapes.[22]

Heraldic charges can be displayed in their natural colors. Many natural items such as plants and animals are described as proper in this case. Proper charges are very frequent as crests and supporters. Overuse of the tincture "proper" is viewed as decadent or bad practice.

Divisions of the field

The field of a shield in heraldry can be divided into more than one tincture, as can the various heraldic charges. Many coats of arms consist simply of a division of the field into two contrasting tinctures. Since these are considered divisions of a shield the rule of tincture can be ignored. For example, a shield divided azure and gules would be perfectly acceptable. A line of partition may be straight or it may be varied. The variations of partition lines can be wavy, indented, embattled, engrailed, nebuly, or made into myriad other forms; see Line (heraldry).[23]

Ordinaries

In the early days of heraldry, very simple bold rectilinear shapes were painted on shields. These could be easily recognized at a long distance and could be easily remembered. They therefore served the main purpose of heraldry—identification.[24] As more complicated shields came into use, these bold shapes were set apart in a separate class as the "honorable ordinaries." They act as charges and are always written first in blazon. Unless otherwise specified they extend to the edges of the field. Though ordinaries are not easily defined, they are generally described as including the cross, the fess, the pale, the bend, the chevron, the saltire, and the pall.[25]

There is a separate class of charges called sub-ordinaries which are of a geometrical shape subordinate to the ordinary. According to Friar, they are distinguished by their order in blazon. The sub-ordinaries include the inescutcheon, the orle, the tressure, the double tressure, the bordure, the chief, the canton, the label, and flaunches.[26]

Ordinaries may appear in parallel series, in which case blazons in English give them different names such as pallets, bars, bendlets, and chevronels. French blazon makes no such distinction between these diminutives and the ordinaries when borne singly. Unless otherwise specified an ordinary is drawn with straight lines, but each may be indented, embattled, wavy, engrailed, or otherwise have their lines varied.[27]

Charges

A charge is any object or figure placed on a heraldic shield or on any other object of an armorial composition.[28] Any object found in nature or technology may appear as a heraldic charge in armory. Charges can be animals, objects, or geometric shapes. Apart from the ordinaries, the most frequent charges are the cross—with its hundreds of variations—and the lion and eagle. Other common animals are stags, Wild Boars, martlets, and fish. Dragons, unicorns, griffins, and more exotic monsters appear as charges and as supporters.

Animals are found in various stereotyped positions or attitudes. Quadrupeds can often be found rampant—standing on the left hind foot. Another frequent position is passant, or walking, like the lions of the coat of arms of England. Eagles are almost always shown with their wings spread, or displayed.

In English heraldry the crescent, mullet, martlet, annulet, fleur-de-lis, and rose may be added to a shield to distinguish cadet branches of a family from the senior line. These cadency marks are usually shown smaller than normal charges, but it still does not follow that a shield containing such a charge belongs to a cadet branch. All of these charges occur frequently in basic undifferenced coats of arms.[29]

Marshalling

Marshalling is the art of correctly arranging armorial bearings.[30] Two or more coats of arms are often combined in one shield to express inheritance, claims to property, or the occupation of an office. Marshalling can be done in a number of ways, but the principal mode is impalement, which replaced the earlier dimidiation which simply halves the shields of both and sticks them together. Impalement involves using one shield with the arms of two families or corporations on either half. Another method is called quartering, in which the shield is divided into quadrants. This practice originated in Spain after the 13th century.[31] One might also place a small inescutcheon of a coat of arms on the main shield.

When more than four coats are to be marshaled, the principle of quartering may be extended to two rows of three (quarterly of six) and even further. A few lineages have accumulated hundreds of quarters, though such a number is usually displayed only in documentary contexts.[32] Some traditions, like the Scottish one, have a strong resistance to allowing more than four quarters, and use instead grand quartering and counter quartering (quarterly quarterly).

Helm and crest

In English the word "crest" is commonly used to refer to a coat of arms—an entire heraldic achievement. The technical use of the heraldic term crest refers to just one component of a complete achievement. The crest rests on top of a helmet which itself rests on the most important part of the achievement: the shield.

The modern crest has evolved from the three-dimensional figure placed on the top of the mounted knights' helms as a further means of identification. In most heraldic traditions a woman does not display a crest, though this tradition is being relaxed in some heraldic jurisdictions, and the stall plate of Lady Marion Fraser in the Thistle Chapel in St Giles, Edinburgh, shows her coat on a lozenge but with helmet, crest and motto.

The crest is usually found on a wreath of twisted cloth and sometimes within a coronet. Crest-coronets are generally simpler than coronets of rank, but several specialized forms exist; for example, in Canada, descendants of the United Empire Loyalists are entitled to use a Loyalist military coronet (for descendants of members of Loyalist regiments) or Loyalist civil coronet (for others).

When the helm and crest are shown, they are usually accompanied by a mantling. This was originally a cloth worn over the back of the helmet as partial protection against heating by sunlight. Today it takes the form of a stylized cloak hanging from the helmet.[33] Typically in British heraldry, the outer surface of the mantling is of the principal color in the shield and the inner surface is of the principal metal, though peers in the United Kingdom use standard colourings regardless of rank or what the colourings of their arms. The mantling is sometimes conventionally depicted with a ragged edge, as if damaged in combat, though the edges of most are simply decorated at the emblazoner's discretion.

Clergy often refrain from displaying a helm or crest in their heraldic achievements. Members of the clergy may display appropriate head wear. This often takes the form of a small crowned, wide brimmed hat, sometimes, outwith heraldry, called a galero with the colors and tassels denoting rank; or, in the case of Papal arms until the inauguration of Pope Benedict XVI in 2005, an elaborate triple crown known as a tiara. Benedict broke with tradition to substitute a mitre in his arms. Orthodox and Presbyterian clergy do sometimes adopt other forms of head gear to ensign their shields. In the Anglican tradition, clergy members may pass crests on to their offspring, but rarely display them on their own shields.

Mottoes

An armorial motto is a phrase or collection of words intended to describe the motivation or intention of the armigerous person or corporation. This can form a pun on the family name as in Thomas Nevile's motto "Ne vile velis." Mottoes are generally changed at will and do not make up an integral part of the armorial achievement. Mottoes can typically be found on a scroll under the shield. In Scottish heraldry where the motto is granted as part of the blazon, it is usually shown on a scroll above the crest, and may not be changed at will. A motto may be in any language.

Supporters and other insignia

Supporters are human or animal figures or, very rarely, inanimate objects, usually placed on either side of a coat of arms as though supporting it. In many traditions, these have acquired strict guidelines for use by certain social classes. On the European continent, there are often fewer restrictions on the use of supporters.[34] In the United Kingdom only peers of the realm, a few baronets, senior members of orders of knighthood, and some corporate bodies are granted supporters. Often these can have local significance or a historical link to the armiger.

If the armiger has the title of baron, hereditary knight, or higher, he or she may display a coronet of rank above the shield. In the United Kingdom this is shown between the shield and helmet, though it is often above the crest in Continental heraldry.

Another addition that can be made to a coat of arms is the insignia of a baronet or of an order of knighthood. This is usually represented by a collar or similar band surrounding the shield. When the arms of a knight and his wife are shown in one achievement, the insignia of knighthood surround the husband's arms only, and the wife's arms are customarily surrounded by a meaningless ornamental garland of leaves for visual balance.[35]

Differencing and Cadency

Since arms pass from parents to offspring, and there are frequently more than one child per couple, a system became necesary to distinguish the arms of siblings and extended family members from the original arms, as passed on through the direct male line, from eldest son to eldest son. This process involves marks of cadency, which are a recognised series of ordinaries which designate a person's relationship to the original armiger. Arms displaying these marks of cadency are thus refered to as differenced, and the process is known as differencing.[36]

In the generation and assumption of new arms, by people who are unable to trace their line back to a recognised armiger, it is common practice to adopt the arms of a person or institution who has contributed to the new armiger's life in some meaningful fashion, and to difference those arms to distinguish the new armorial bearing from the inspiring original.

National styles

The emergence of heraldry occurred across western Europe almost simultaneously in the various countries. Originally, heraldic style was very similar from country to country.[37] Over time, there developed distinct differences between the heraldic traditions of different countries. The four broad heraldic styles are German-Nordic, Gallo-British, Latin, and Eastern.[38] In addition it can be argued that later national heraldic traditions, such as South African and Canadian have emerged in the twentieth century.[39] In general there are characteristics shared by each of the four main groups.

German-Nordic heraldry

Coats of arms in Germany, the Scandinavian countries, Estonia, Latvia, Czech lands and northern Switzerland generally change very little over time. Marks of difference are very rare in this tradition as are heraldic furs.[40] One of the most striking characteristics of German-Nordic heraldry is the treatment of the crest. Often, the same design is repeated in the shield and the crest. The use of multiple crests is also common.[41] The crest cannot be used separately as in British heraldry, but can sometimes serve as a mark of difference between different branches of a family.[42] Torse is optional.[43] Heraldic courtoisie is observed.[44]

Dutch heraldry

The Low Countries were great centres of heraldry in medieval times. One of the famous armorials is the Gelre Armorial or Wapenboek, written between 1370 and 1414. Coats of arms in the Netherlands were not controlled by an official heraldic system like the two in the United Kingdom, nor were they used solely by noble families. Any person could develop and use a coat of arms if they wished to do so, provided they did not usurp someone else's arms, and historically, this right was enshrined in Roman Dutch law[45]. As a result, many merchant families had coats of arms even though they were not members of the nobility. These are sometimes referred to as burgher arms, and it is thought that most arms of this type were adopted while the Netherlands was a republic (1581-1806). This heraldic tradition was also exported to the erstwhile Dutch colonies.[46]

Dutch heraldry is characterised by its simple and rather sober style, and in this sense, is closer to its medieval origins than the eloborate styles which developed in other heraldic traditions.[47]

Gallo-British heraldry

The use of cadency marks to difference arms within the same family and the use of semy fields are distinctive features of Gallo-British heraldry. It is common to see heraldic furs used.[48] In the United Kingdom, the style is notably still controlled by royal officers of arms.[49] French heraldry experienced a period of strict rules of construction under the Emperor Napoleon.[50] English and Scots heraldries make greater use of supporters than other European countries.[41]

Latin heraldry

The heraldry of southern France, Portugal, Spain, and Italy is characterized by a lack of crests, and uniquely-shaped shields.[51] Portuguese and Spanish heraldry occasionally introduce words to the shield of arms, a practice disallowed in British heraldry. Latin heraldry is known for extensive use of quartering, because of armorial inheritance via the male and the female lines. Moreover, Italian heraldry is dominated by the Roman Catholic Church, featuring many shields and achievements, most bearing some reference to the Church.[52]

Central and Eastern European heraldry

Eastern European heraldry is in the traditions developed in Serbia, Croatia, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Ukraine, and Russia. Eastern coats of arms are characterized by a pronounced, territorial, clan system — often, entire villages or military groups were granted the same coat of arms irrespective of family relationships. In Poland, nearly six hundred unrelated families are known to bear the same Jastrzębiec coat of arms. Marks of cadency are almost unknown, and shields are generally very simple, with only one charge. Many heraldic shields derive from ancient house marks. At the least, fifteen per cent of all Hungarian personal arms bear a decapitated Turk's head, referring to their wars against the Ottoman Empire.[53][54]

Modern heraldry

Heraldry flourishes in the modern world; institutions, companies, and private persons continue using coats of arms as their pictorial identification. In the United Kingdom and Ireland, the English Kings of Arms, Scotland's Lord Lyon King of Arms, and the Chief Herald of Ireland continue making grants of arms.[55] There are heraldic authorities in Canada,[56] South Africa, Spain, and Sweden that grant or register coats of arms. In South Africa, the right to armorial bearings is also determined by Roman Dutch law, inherited from the 17th century Netherlands.[57]

Heraldic societies abound in Africa, Asia, Australasia, the Americas, and Europe. Heraldry aficionados participate in the Society for Creative Anachronism, medieval revivals, micronationalism, et cetera. People see heraldry as a part of their national and personal heritages, and as a manifestation of civic and national pride. Today, heraldry is not a worldly expression of aristocracy, merely a form of identification.[58]

Military heraldry continues developing, incorporating blazons unknown in the medieval world. Nations and their subdivisions — provinces, states, counties, cities, etc. — continue building upon the traditions of civic heraldry. The Roman Catholic Church, the Church of England, and other Churches maintain the tradition of ecclesiastical heraldry for their high-rank prelates, holy orders, universities, and schools.

As a result of the burgeoning middle classes in Victorian times, there was a great desire for many non-armigers to possess arms, to enhance their social standing and avoid the appearance of being "new money"[citation needed]. As a result, a great many people have the misconception that they are entitled to use a "family crest", when, in fact, the "crest" in question is actually the armorial achievment of an individual with the same last name. As arms are intended to identify individual entities or persons, rather than families, the "family crest" is something of a myth[citation needed]. The Scottish Clan badge system, which can be applicable to many individuals in the one family or clan, may contribute to this misunderstanding of the correct use of an armorial achievment among laypeople[citation needed]. Bogus "family crests" continue to be sold by unscrupulous bucket shops to unsuspecting customers.[citation needed]

Extended bibliography

General heraldry

- Fox-Davies, A.C.. The Art of Heraldry: An Encyclopedia of Armory.

- Parker, James. A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry. Oxford: James Parker & Co., 1894 (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1970).

United Kingdom

- Burke, John Bernard. The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales; Comprising a Registry of Armorial Bearings from the Earliest to the Present Time. London: Burke's Peerage, 1884 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1967).

- as above, but the original title page offers slightly different information, viz: by Sir Bernard Burke, C.B., LL.D., Ulster King of Arms, London, Harrison, 59, Pall Mall, 1884.

- Dennys, Rodney. The Heraldic Imagination. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1975.

- Elvins, Mark Turnham. Cardinals and Heraldry (Illustrated by Anselm Baker, foreword by Maurice Noël Léon Couve de Murville, preface by John Brooke-Little). London: Buckland Publications, 1988.

- Fairbairn, James. Fairbairn's Crests of the Families of Great Britain & Ireland. 2v. Revised ed. New York: Heraldic Publishing Co., 1911 (New York: Bonanza Books, 1986 in 1 vol.). Originally published 1800.

- Humphery-Smith, Cecil. Ed and Augmented General Armory Two, London, Tabard Press, 1973.

- Sir Thomas Innes of Learney "Scots Heraldry" 2nd ed, Edinburgh and London: Oliver and Boyd, 1956

- Paul, James Balfour. An Ordinary of Arms Contained in the Public Register of All Arms and Bearings in Scotland. Edinburgh: W. Green & Sons, 1903.

- Wagner, Sir Anthony R. Heralds of England: A History of the Office and College of Arms. London: HMSO, 1967.

Mainland Europe

- Le Févre, Jean. A European Armorial: An Armorial of Knights of the Golden Fleece and 15th Century Europe. (Edited by Rosemary Pinches & Anthony Wood) London: Heraldry Today, 1971.

- Louda, Jiří and Michael Maclagan. Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe. New York: Clarkson Potter, 1981. Reprinted as Lines of Succession (London: Orbis, 1984).

- Rietstap, Johannes B. Armorial General. The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1904-26 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1967).

- Siebmacher, Johann. J. Siebmacher's Grosses und Allgemeines Wappenbuch Vermehrten Auglage. Nürnberg: Von Bauer & Raspe, 1890-1901.

Civic Heraldry

See also

Notes

- ^ Stephen Friar, Ed. A Dictionary of Heraldry. (Harmony Books, New York: 1987), 183.

- ^ Fox-Davies, A Complete Guide to Heraldry, (Thomas Nelson, 1925).

- ^ Iain Moncreiffe of that Ilk & Pottinger, Simple Heraldry (Thomas Nelson, 1953).

- ^ John Brooke-Little. An Heraldic Alphabet. (Macdonald, London: 1973),2.

- ^ Notitia Dignitatum, Bodleian Library

- ^ C. A. Stothard, Monumental Effigies of Great Britain (1817) pl. 2, illus. in Wagner, Anthony, Richmond Herald, Heraldry in England (Penguin, 1946), pl. I.

- ^ Beryl Platts. Origins of Heraldry. (Procter Press, London: 1980), 32.

- ^ Woodcock, Thomas & John Martin Robinson. The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. (Oxford University Press, New York: 1988), 1.

- ^ Wagner 1946:8.

- ^ Squibb, George. (Spring 1953). "The Law of Arms in England". The Coat of Arms II (15): 244.

- ^ Jack Carlson. A Humorous Guide to Heraldry. (Black Knight Books, Boston: 2005), 22

- ^ David Williamson. Debrett's Guide to Heraldry and Regalia. (Headline Books, London: 1992), 24.

- ^ Arthur Fox-Davies. A Complete Guide to Heraldry (Grammercy Books, New York: 1993), 99.

- ^ William Whitmore. The Elements of Heraldry. (Weathervane Books, New York: 1968), p.9.

- ^ Government of Nunavut. n.d. About the Flag and Coat of Arms. Government of Nunavut, Iqaluit, NU, Canada. Accessed October 19, 2006. Available here

- ^ Hartemink R. 1996. South African Civic Heraldry-Bophuthatswana. Ralf Hartemink, The Netherlands. Accessed October 19, 2006. Available here

- ^ US Heraldic Registry

- ^ American Heraldry Society - Arms of Connecticut

- ^ Stephen Slater. The Complete Book of Heraldry. (Hermes House, New York: 2003), p.56.

- ^ Bruno Heim. Or and Argent (Gerrards Cross, Buckingham: 1994).

- ^ Michel Pastoureau. Heraldry: An Introduction to a Noble Tradition. (Henry N Abrams, London: 1997), 47.

- ^ Thomas Innes of Learney. Scots Heraldry (Johnston & Bacon, London: 1978), 28.

- ^ Stephen Friar and John Ferguson. Basic Heraldry. (W.W. Norton & Company, New York: 1993), 148.

- ^ Carl-Alexander von Volborth. Heraldry: Customs, Rules, and Styles. (Blandford Press, Dorset: 1981), 18.

- ^ Stephen Friar, Ed. A Dictionary of Heraldry. (Harmony Books, New York: 1987), 259.

- ^ Stephen Friar, Ed. A Dictionary of Heraldry. (Harmony Books, New York: 1987), 330.

- ^ Woodcock, Thomas & John Martin Robinson. The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. (Oxford University Press, New York: 1988), 60.

- ^ John Brooke-Little. Boutell's Heraldry. (Frederick Warne & Company, London: 1973), 311.

- ^ Iain Moncreiffe of that Ilk and Don Pottinger. Simple Heraldry, Cheerfully Illustrated. (Thomas Nelson and Sons, London: 1953), 20.

- ^ David Williamson. Debrett's Guide to Heraldry and Regalia. (Headline Books, London: 1992), 128.

- ^ Thomas Woodcock & John Martin Robinson. The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. (Oxford University Press, New York: 1988), 14.

- ^ Edmundas Rimša. Heraldry Past to Present. (Versus Aureus, Vilnius: 2005), 38.

- ^ Peter Gwynn-Jones. The Art of Heraldry. (Parkgate Books, London: 1998), 124.

- ^ Ottfried Neubecker. Heraldry: Sources, Symbols, and Meaning. (Tiger Books International, London: 1997), 186.

- ^ Julian Franklyn. Shield and Crest. (MacGibbon & Kee, London: 1960), 358.

- ^ http://www.baronage.co.uk/jag-ht/jag008.html

- ^ Davies, T.R. (Spring 1976). "Did National Heraldry Exist?". The Coat of Arms NS II (97): 16.

- ^ von Warnstedt, Christopher. (October 1970). "The Heraldic Provinces of Europe". The Coat of Arms XI (84): 128.

- ^ Alan Beddoe, revised by Strome Galloway. Beddoe's Canadian Heraldry. (Mika Publishing Company, Belleville: 1981).

- ^ von Warnstedt, Christopher. (October 1970). "The Heraldic Provinces of Europe". The Coat of Arms XI (84): 129.

- ^ a b Thomas Woodcock & John Martin Robinson. The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. (Oxford University Press, New York: 1988), 15.

- ^ Neubecker, Ottfried. Heraldry. Sources, Symbols and Meaning (London 1976), p. 158

- ^ Pinches, J.H: European Nobility and Heraldry . (Heraldry Today, 1994, ISBN 0-900455-45-4, p. 82

- ^ Carl-Alexander von Volborth. Heraldry: Customs, Rules, and Styles. (Blandford Press, Dorset: 1981), p. 88.

- ^ J.A. de Boo. Familiewapens, oud en nieuw. Een inleiding tot de Familieheraldiek. (Centraal Bureau voor Genealogie, The Hague: 1977)

- ^ Roosevelt Coats of Arms: Theodore and Franklin Delano at American Heraldry Society. Accessed January 20, 2007.

- ^ Cornelius Pama Heraldiek in Suid-Afrika. (Balkema, Cape Town: 1956).

- ^ von Warnstedt, Christopher. (October 1970). "The Heraldic Provinces of Europe". The Coat of Arms XI (84): 129.

- ^ Carl-Alexander von Volborth. Heraldry of the World. (Blandford Press, Dorset: 1979), 192.

- ^ Thomas Woodcock & John Martin Robinson. The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. (Oxford University Press, New York: 1988), 21.

- ^ von Warnstedt, Christopher. (October 1970). "The Heraldic Provinces of Europe". The Coat of Arms XI (84): p.129.

- ^ Thomas Woodcock & John Martin Robinson. The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. (Oxford University Press, New York: 1988), pp.24-30.

- ^ von Warnstedt, Christopher. (October 1970). "The Heraldic Provinces of Europe". The Coat of Arms XI (84): pp.129-30.

- ^ Thomas Woodcock & John Martin Robinson. The Oxford Guide to Heraldry. (Oxford University Press, New York: 1988), 28-32.

- ^ See the College of Arms newsletter for quarterly samplings of English grants and the Chief Herald of Ireland's webpage for recent Irish grants.

- ^ See the Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada at this page

- ^ Cornelius Pama. Heraldry of South African families: coats of arms/crests/ancestry. (Balkema, Cape Town: 1972)

- ^ Stephen Slater. The Complete Book of Heraldry. (Hermes House, New York: 2003), p.238.

External links

- Portal:Heraldry/Web resources

- Puncher Heraldry Program

- Coat of Arms Visual Designer web-based software

- Free access to Burke's General Armory (incomplete, 1,500 British surnames), Pimbley's Dictionary of Heraldry and Blason des familles d'Europe, Grand Armorial Universel (15,000 European surnames)