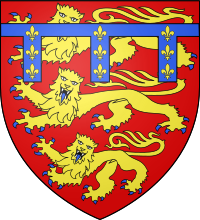

House of Lancaster

| House of Lancaster | |

|---|---|

| |

| Parent house | House of Plantagenet |

| Country | Kingdom of England, Kingdom of France |

| Founded | 30 June 1267 |

| Founder | Edmund Crouchback |

| Current head | Extinct in the male line |

| Final ruler | Henry VI of England |

| Titles | Earl of Lancaster Earl of Leicester Count of Champagne and Brie Lord of Beaufort and Nogent Earl of Moray Earl Ferrers Earl of Derby Earl of Salisbury Earl of Lincoln Duke of Lancaster King of England, King of France |

| Estate(s) | England |

| Dissolution | 1471 |

The House of Lancaster was a cadet branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. Henry III of England created the Earldom of Lancaster from which the house was named for his second son, Edmund Crouchback, in 1267. Edmund had already been created Earl of Leicester in 1265 and granted the lands and privileges of Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester after de Montfort's death and attainder at the end of the Second Barons' War.[1] It was through descent from Edmund rather than from the main Plantagenet line that the three Lancastrian monarchs legitimatised their reigns.[2]

When Edmund's son, Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, inherited his father-in-law's title of Earl of Lincoln and estates he became at a stroke the most powerful nobleman in England with lands throughout the kingdom and the ability to raise vast private armies to wield power at national and local level.[3] This brought the Earls of Lancaster into conflict with their cousin Edward II of England before they gave loyal service to his son Edward III of England.

Edward III married all his sons to wealthy English heiresses rather than follow his predecessors' practice of finding continental political marriages for royal princes. Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster, had no male heir so Edward married his son John to Henry's heiress daughter and John's third cousin, Blanche of Lancaster. This gave John the vast wealth of the House of Lancaster which some take as the founding of the Royal House. Their son, Henry, usurped the throne in 1399 thereby creating one of the factions in the Wars of the Roses. These were an intermittent dynastic struggle between the descendants of Edward III. In these wars the term Lancastrian became a reference to both members of the family and their supporters. The family provided England with three kings: Henry IV of England, who ruled 1399–1413; Henry V of England, who ruled 1413–1422; and Henry VI of England who ruled 1422–1461 and 1470–1471.

The House became extinct in the male line on the murder of Henry VI following the execution of his son, Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales, by supporters of the House of York in 1471.

Origin of the Earls of Lancaster

After Henry III of England's supporters suppressed opposition from the English nobility in the Second Barons' War, he granted to his second son, Edmund Crouchback, the titles and possessions forfeited by attainder of the Barons' leader, Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester. These included Earl of Leicester on 26 October 1265, the first Earldom of Lancaster on 30 June 1267 and Earl Ferrers in 1301. Edmund was also Count of Champagne and Brie from 1276 by right of his wife[1] Henry IV of England would later use his descent from Edmund to legitimise his claim to the throne, even going as far to make the spurious claim that Edmund was the elder son of Henry but had been passed over as king due to his deformity.[2]

Edmund's second marriage to the widow of the King of Navarre, Blanche of Artois, placed him at the centre of the European aristocracy. Her daughter, Joan I of Navarre, was queen regnant of Navarre and through her marriage to Philip IV of France queen consort of France. Edmund's son, Thomas, became the most powerful nobleman in England gaining the Earldoms of Lincoln and Salisbury through marriage to the heiress of Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln. His income was £11,000 per annum, double that of the next most senior earl.[3]

Thomas and his brother, Henry, served in the coronation of their cousin, King Edward II of England on 25 February 1308 with Thomas carrying a great sword and Henry the royal sceptre.[4] After initially supporting Edward, Thomas became one of the Lords Ordainers who demanded the banishment of Piers Gaveston and the governance of the realm by a baronial council. After Gaveston was captured Thomas took the lead in his trial and execution at Warwick in 1312.[5] Edward's authority was weakened by poor governance and defeat by the Scots at the Battle of Bannockburn. This allowed Thomas to republish the Ordinances of 1311 restraining Edwards power. Thomas saw this as an end in itself and he retreated to Pontefract Castle taking little part in the governance of the realm.[6] This allowed Edward to regroup and rearm leading to a fragile peace in August 1318 with the Treaty of Leake. Edward's rule collapsed into anarchy again in 1321. Thomas raised a northern army but was defeated and captured at the Battle of Boroughbridge. In a show trial he was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered but as Edward's cousin this was commuted to beheading.[7]

Thomas's younger brother Henry joined the revolt of Edward's wife, Isabella of France, and her lover, Mortimer, in 1326, pursuing and capturing Edward at Neath in South Wales.[7] Following Edward's deposition at the Parliament of Kenilworth in 1326 and reputed murder at Berkeley Castle,[8] Thomas's conviction was posthumously reversed and Henry regained possession of the Earldoms of Lancaster, Derby, Salisbury and Lincoln that had been forfeit for Thomas's treason. It would be Henry who would knight the young King Edward III of England before his coronation.[9] Mortimer lost support over the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton that agreed independence for Scotland and provoked jealousy from the barons in developing power in the Welsh Marches. So when he called a parliament to make this permanent in the title of Earl of March in 1328 Henry led the opposition holding a counter-meeting. In response, Mortimer ravaged the lands of Lancaster and checked the revolt. The Barons were too divided overthrow the regime but Edward III was able to assume control in 1330.[10]

Duchy and Palatinate of Lancaster

Henry's son, also called Henry was born at the castle of Grosmont in Monmouthshire between 1299 and 1314.[11] According to his memoirs he was better at martial arts than academic subjects and did not learn to read until later in life.[12] Henry was co-eval with Edward and was pivotal to his reign, becoming his best friend and most trusted commander.[13] He was knighted in 1330, represented his father in parliament and took part in Edward's Scottish campaign.[14] After the outbreak of the Hundred Years' War he took part in several diplomatic missions and minor campaigns and was present at the great English victory in the naval Battle of Sluys in 1340.[15] Later, he was required to commit himself as hostage in the Low Countries for the king's considerable debts, remaining hostage for a year and having to pay a large ransom for his own release.[16]

In 1345 Edward III launched a major three-pronged attack on France. Earl of Northampton attacked from Brittany, the king from Flanders and Grosmont was to prepare a campaign from Aquitaine in the south.[13] Moving rapidly through the country, he confronted the Comte d'Isle at the Battle of Auberoche and achieved a victory described as "the greatest single achievement of Lancaster's entire military career".[17] The ransom from the prisoners has been estimated at £50,000.[18] The king rewarded Henry by including him as a founding knight of the Order of the Garter.[19] An even greater honour was bestowed on Lancaster when he created him Duke of Lancaster. The title of duke was of relatively new origin in England with only Cornwall being a previous ducal title. Lancaster was also given palatinate status for the county of Lancashire, which entailed a separate administration independent of the crown.[20] There were only two other counties palatine: Durham, which was an ancient ecclesiastical palatinate, and Chester, which was crown property. It is a sign of Edward's high regard for Lancaster that he would bestow such extensive privileges on him.

In 1350 Henry was present at the naval victory at Winchelsea where he saved the life of the Black Prince.[21] He spent 1351-2 on crusade in Prussia where a quarrel with Otto, Duke of Brunswick almost led to a duel between the two men, only averted by the intervention of the French king, John II.[22] As campaigning in France resumed Henry participated in the last great offensive of the first phase of the Hundred Years' War: the Rheims campaign of 1359–60 before returning to England where he fell ill and died at Leicester Castle, most likely of the plague.[22]

Edward III of England married his third surviving son, John of Gaunt to Henry's heiress Blanche of Lancaster. On Henry's death Edward conferred on Gaunt the second creation of the title of Duke of Lancaster which made Gaunt the wealthiest landowner in England after the King. Gaunt enjoyed great political influence during his lifetime, but upon his death in 1399, his lands were confiscated by Richard II. Gaunt's exiled son and heir Henry of Bolingbroke returned home the same year with an army to reclaim the Lancaster estates, but ended up riding a tide of popular opposition to Richard II that saw him take control of the Kingdom. Richard surrendered to Henry’s forces at Conwy Castle recognising that he had insufficient support to resist. Henry then ignored the promise that he only wished for the restoration of his Lancaster inheritance and instigated a commission to decide who should be King. Richard was forced to abdicate and even though Henry was not next in line he was declared King by an unlawfully constituted parliament dominated by his supporters.[23]

After the first unrest of his reign and a revolt by the Earls of Salisbury, Gloucester, Exeter and Surrey Henry ended the risk of restoration by reputedly having Richard starved to death in order that there would be incriminating marks on the body.[24]

The reign of Henry IV

Henry's accession by force broke the principles of Plantagenet succession; from this point any magnate with sufficient power and Plantagenet blood could have ambitions to assume the throne. His assertion that his mother had legitimate rights through descent from Edmund Crouchback, whom he claimed was the elder son of Henry III of England, set aside due to deformity, was not widely believed. Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, was the heir presumptive to Richard II by being the grandson of Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, but as a child he was not considered a serious contender and as an adult never showed any interest in the throne, instead loyally served the House of Lancaster. When Richard of Conisburgh, 3rd Earl of Cambridge, plotted to use him to displace Henry's newly crowned son, and their mutual cousin, he informed the new King and the plotters were executed. However, the marriage of his sister to Conisborough, son of Edward III's fourth son Edmund of Langley consolidated the Anne's claim to the throne with that of the more junior House of York.[2]

Henry was plagued with financial problems, the political need to reward his supporters, frequent rebellions and declining health, including leprosy and epilepsy.[25] The Percy family had been some of Henry's leading supporters, defending the North from Scotland largely at their own expense, but revolted in the face of lack of reward and suspicion from Henry. Henry Percy (Hotspur) was defeated and killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury. In 1405 Hotspur's father, Henry Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland supported Richard le Scrope, Archbishop of York, in another rebellion, after which he fled to Scotland and his estates were confiscated. Henry's subsequent execution of England's premier cleric, comparable with the murder of Thomas Beckett, would probably have led to Henry's excommunication but the church was in schism, with two competing popes keen on Henry's support, and protested but took no action. In 1408 Percy invaded England once more and was killed at the Battle of Bramham Moor.[26] In Wales Owain Glyndŵr's widespread rebellion was only suppressed with the recapture of Harlech Castle in 1409, although sporadic fighting continued until 1421.[27]

Henry IV was succeeded by his son Henry V, and eventually by his grandson Henry VI in 1422.

Henry V and the Hundred Years' War – the Lancastrian war

Henry V of England was a successful and ruthless monarch.[28] He was quick to resume the Hundreds' Year War to re-assert the claim to the French throne he inherited from Edward III. The war was not a formal continuous conflict but an occasion for English raids and military expeditions from 1337 until 1453. There were six major royal expeditions, with Henry himself leading the fifth and sixth, but these were less typical than the smaller frequent provincial campaigns.[29] In Henry's first major campaign, and the fifth major royal campaign of the war, he invaded France, captured Harfleur, made a chevauchée to Calais and won a near total victory over the French at the Battle of Agincourt, despite being outnumbered, outmanoeuvred and low on supplies.[30] In his second campaign, he recaptured much of Normandy and in a treaty secured a marriage to Catherine of Valois. The terms of the Treaty of Troyes were Henry and Catherine's heirs would succeed to the throne of France. However, this was contested by the Dauphin and the momentum of the war turned. Thomas, Duke of Clarence, Henry's brother, was killed in the defeat at the battle of Baugé in 1421 before Henry, himself, died of dysentery at Vincennes.[31] Henry VI of England was less than a year old but led by Henry V's brother John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford the boy King's uncles continued the war. There were more victories, such as the Battle of Verneuil but it was impossible to maintain campaigning at this level. Joan of Arc's involvement helped the French lift of the siege of Orleans[32] and win the Battle of Patay before Joan was captured by the Burgundians, sold to the English, tried as a witch and burned at the stake. The Dauphin was crowned before continuing the successful Fabian tactics of avoiding full frontal assault and exploiting logistical advantage.[33]

Henry VI and the fall of The House of Lancaster

The war caused political division between the Lancastrians and the other Plantagenets during the minority of Henry VI. Bedford wanted to defend Normandy, Humphrey of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Gloucester, just Calais, but Cardinal Beaufort wanted peace.[34] This division led to Gloucester's wife being accused of using witchcraft with the aim of putting him on the throne and he was arrested and died in prison.[35] The refusal to renounce the claim to the French crown at the congress of Arras led to the defection of England's ally Philip III, Duke of Burgundy to Charles and time for the French to reorganise feudal levies into a modern professional army with superior numbers.[36] The French retook Rouen and Bordeaux, regained Normandy, won the Battle of Formigny in 1450[37] and with victory at the Battle of Castillon in 1453 brought an end to the war with the result that all the English holdings in France, except Calais and the Channel Islands, were lost forever.[38]

Henry proved to be a weak king vulnerable to the over-mighty subjects who developed private armies of retainers. Rivalries often spilled over from the courtroom into armed confrontation such as Percy–Neville feud.[39] The common purpose of the war in France had ended and Henry's cousin, Richard, Duke of York, and Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick used their networks to defy the crown. The King became the focus of discontent, as population, agricultural production, prices, wool trade and credit declined in the Great Slump.[40] Most seriously, in 1450 Jack Cade raised a rebellion in an attempt to force the King to address economic problems or abdicate his throne.[41] The uprising was suppressed, but remained deeply unsettling with more radical demands coming from John and William Merfold.[42]

Henry's marriage to Margaret of Anjou prompted criticism from Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York because it included the surrender of Maine and an extended truce with France. York was Henry's cousin through his descent from two of Edward III sons, Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence and Edmund, Duke of York. This gave York political influence but he was removed from English and French politics through his appointment as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.[43] Conscious of the fate of Henry's Uncle Humphrey at the hands of the Beauforts and suspicious that Henry intended to nominate Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset as heir presumptive York recruited militarily on his return to England. Armed conflict was avoided because York lacked aristocratic support and he was forced to swear allegiance to Henry. However, when Henry later had a mental breakdown York was named regent. Henry himself was trusting and not a man of war, but Margaret was more assertive, showing open enmity toward York particularly after the birth of a male heir that resolved the succession question and assured her position.[44]

When Henry's sanity returned the court party reasserted its authority, but York and his relatives, the Nevilles, defeated them at a skirmish called the First Battle of St Albans. Possibly as few as 50 men were killed, but among them were Somerset and the two Percy lords, Henry Percy, 2nd Earl of Northumberland, and Thomas Clifford, 8th Baron de Clifford, creating feuds that would confound reconciliation attempts despite the shock that armed conflict had been to the ruling class.[45][46] Threatened with treason charges and lacking support, York, Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury, and Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, fled abroad. Henry was captured by the opposition when the Nevilles returned, winning the Battle of Northampton.[47] York joined them, surprising parliament by claiming the throne and then forcing through the Act of Accord. This stated that Henry would remain as monarch for his lifetime, but that York would succeed him. The disinheriting of Henry's son Edward was unacceptable to Margaret, so continuing conflict was inevitable. York was killed at the Battle of Wakefield and his head set on display at Micklegate Bar, York along with those of Edmund, Earl of Rutland, and Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury, who had both been captured and beheaded.[48]

Margaret gained the support of the Scottish queen Mary of Guelders and with a Scottish army pillaged into southern England.[49] However, the citizens of London feared the city being plundered and enthusiastically welcomed York's son Edward, Earl of March as King.[50] Margaret's defeat at the Battle of Towton confirmed Edward's position and he was crowned.[51] However, Warwick and Clarence defected to the Lancastrians as a result of disaffection with Edward's marriage to Elizabeth Woodville and preferment of her formerly Lancastrian-supporting family. The alliance was sealed with the marriage of Henry's son, Edward, to Warwick's daughter, Anne. Edward and Richard, Duke of Gloucester fled England. When they returned Clarence switched sides at the Battle of Barnet and Warwick and his brother were killed. Before Henry, Margaret and Edward of Lancaster could escape back to France they were caught at the Battle of Tewkesbury. Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales was executed on the battlefield and John Beaufort, Marquess of Dorset was killed in the fighting meaning that when his brother, Edmund Beaufort, 4th Duke of Somerset, was executed two days later the Beaufort family became extinct in the male line. The captive Henry was murdered on 21 May 1471 in the Tower of London and buried in Chertsey Abbey, extinguishing the House of Lancaster.[52]

Legacy

Shakespeare’s history plays

"This royal throne of kings, this sceptr’d isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall,

Or as a moat defensive to a house

Against the envy of less happier lands;

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England…..

—John of Gaunt’s speech in Richard II,

Act II, Scene I, 40–50[53]

It is a source of irritation to historians that Shakespeare’s influence on the perception of the later medieval period exceeds academic research.[54] While the chronology of Shakespeares’ history plays runs from King John to Henry VIII they are dominated by eight plays in which members of the House of Lancaster play a significant part voicing speeches on a par with those in Hamlet and King Lear.[55] These plays are:

- Richard II

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI, Part 1

- Henry VI, Part 2

- Henry VI, Part 3

- Richard III.

These plays were constrained by the political and religious requirements of Tudor England. While the plays are factually inaccurate they do demonstrate how the past, and the House of Lancaster, is remembered in terms of myth, legend, ideas and popular misconception.[56]

Succession

Lancastrian cognatic descent from John of Gaunt and Blanche's daughter Phillipa continued in the royal houses of Spain and Portugal.[57] However, the remnants of the Lancastrian court party coalesced support around Henry Tudor, albeit a relatively unknown scion of the Beauforts. They had been amongst the most ardent supporters of the House of Lancaster and were descended illegitimately from John of Gaunt by his mistress Katherine Swynford. Although later legitimised by Richard II, Henry IV had formally and permanently debarred them from the succession to avoid competition with the House of Lancaster’s claims to the throne. In addition by some calculations of primogeniture there were as many as 18 people with more right to the throne including both his mother and future wife. By 1510 this figure had increased by the birth of an additional 16 possible Yorkist claimants.[58]

With the House of Lancaster extinct Henry claimed to be the Lancastrian heir through his mother Lady Margaret Beaufort. On the paternal side his father had been Henry VI's maternal half-brother. In 1485 Henry Tudor united increasing opposition within England to the reign of Richard III with the Lancastrian cause to take the throne. To legitimise his questionable claim, Henry married the daughter of Edward IV of England, Elizabeth of York and promoted the House of Tudor as a dynasty of dual Lancastrian and Yorkist descent.[59]

Education and Architecture

Henry VI continued the architectural patronage begun by his father, founding both Eton College and King's College, Cambridge and leaving a lasting educational and architectural legacy in buildings including King's College Chapel and Eton College Chapel.[60]

Earls & Dukes of Lancaster (first creation)

Dukes of Lancaster (second creation)

| Duke | Portrait | Birth | Marriage(s) | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John of Gaunt Earl by right of his wife, the title Duke of Lancaster was vacant due to the lack of male heirs. Created Duke by his father Edward III of England |

|

6 March 1340 Ghent son of Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault |

Blanche of Lancaster 1359 7 children See above Constance of Castile 21 September 1371 2 children Catherine, Queen of Castile John Katherine Swynford 13 January 1396 4 children House of Beaufort John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset Cardinal Henry Beaufort Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter Joan Beaufort, Countess of Westmorland |

3 February 1399 Leicester Castle age 58 |

Lancastrian Kings of England

See also

- Knighton's Chronicon

- Quia Emptores

- Lancashire

- Philippa of Lancaster

- Jorge de Lencastre, Duke of Coimbra

- John of Lencastre, 1st Duke of Aveiro

References

- ^ a b c Weir 2008, p. 75

- ^ a b c Weir 1995, p. 40 Cite error: The named reference "Weir1995" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Jones 2012, pp. 371

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 363

- ^ Jones 2012, pp. 375–8

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 390

- ^ a b Jones 2012, p. 400

- ^ Davies 1999, p. 381

- ^ Jones 2012, p. 422

- ^ Lee 1997, p. 115

- ^ a b c Weir 2008, p. 77

- ^ Fowler 1969, p. 26

- ^ a b Jones 2012, p. 471

- ^ Fowler 1969, p. 30

- ^ Fowler 1969, p. 34

- ^ Fowler 1969, pp. 35–7

- ^ Fowler 1969, pp. 58–9

- ^ Fowler 1969, p. 61

- ^ McKisack 1959, pp. 252

- ^ Fowler 1969, pp. 173–4

- ^ Fowler 1969, pp. 193–5

- ^ a b Fowler 1969, pp. 106–9 Cite error: The named reference "fowler106" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Weir 1995, pp. 36–9

- ^ Weir 1995, p. 44

- ^ Swanson 1995, p. 298.

- ^ Lee 1997, pp. 138–41

- ^ Davies, R R (1995). The Revolt of Owain Glyn Dwr. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 293. ISBN 0-19-280209-7.

- ^ Schama 2000, pp. 265–6

- ^ Davies 1997, pp. 419–20

- ^ Schama 2000, p. 265

- ^ Weir 2008, pp. 133

- ^ Davies 1999, pp. 76–80

- ^ Weir 1995, pp. 82–3

- ^ Weir 1995, pp. 72–6

- ^ Weir 1995, pp. 122–32

- ^ Weir 1995, pp. 86, 101

- ^ Weir 1995, pp. 156

- ^ Weir 1995, pp. 172

- ^ Schama 2000, p. 266

- ^ Hicks 2010, p. 44

- ^ Weir 1995, pp. 147–55

- ^ Mate 2006, p. 156

- ^ Crofton 2007, p. 112.

- ^ Crofton 2007, p. 111.

- ^ Goodman 1981, p. 25.

- ^ Goodman 1981, p. 31.

- ^ Goodman 1981, p. 38.

- ^ Weir 1995, p. 257

- ^ Goodman 1981, p. 57.

- ^ Goodman 1981, p. 1.

- ^ Goodman 1981, p. 147.

- ^ Weir 2008, p. 134

- ^ Davies 1999, p. 508

- ^ Davies 1999, p. 506

- ^ Davies 1999, p. 507

- ^ Davies 1999, p. 509

- ^ a b Weir 2008, p. 100

- ^ Weir 2008, p. 148

- ^ Weir 2008, pp. 146–9

- ^ Weir 1995, p. 94

- ^ Weir 2008, pp. 76–7

- ^ Weir 2008, p. 124

- ^ Weir 2008, p. 130

- ^ Weir 2008, p. 133

Bibliography

- Crofton, Ian (2007). The Kings and Queens of England. Quercus. ISBN 1-84724-065-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Norman (1997). Europe – A History. Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-6633-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Norman (1999). The Isles – A History. MacMillan. ISBN 0-333-76370-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fowler, Kenneth Alan (1969). The King's Lieutenant: Henry of Grosmont, First Duke of Lancaster, 1310–1361. London. ISBN 0-236-30812-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Goodman, Anthony (1981). The Wars of the Roses: Military Activity and English Society, 1452–97. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-05264-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hicks, Michael (2010). The Wars of the Roses. Yale University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jones, Dan (2012). The Plantagenets: The Kings Who Made England. HarperPress. ISBN 0-00-745749-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lee, Christopher (1997). This Sceptred Isle. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-1-84529-994-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mate, Mavis (2006). Trade and Economic Developments 1450–1550: The Experience of Kent, Surrey and Sussex. Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-189-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McKisack, M. (1959). The Fourteenth Century: 1307–1399. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-821712-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Schama, Simon (2000). A History of Britain – At the edge of the world. BBC. ISBN 0-563-53483-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Swanson, R.N. (1995). Religion and Devotion in Europe, c. 1215-c. 1515. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37950-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Weir, Alison (1995). Lancaster & York – The Wars of the Roses. Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-6674-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Weir, Alison (2008). Britain's Royal Families. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-953973-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Nuttall, Jenni, The Creation of Lancastrian England: Literature, Language and Politics in Late Medieval England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007) (Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature, 67).

External links

- House of Lancaster on the official website of the British monarchy