Livonian War: Difference between revisions

→Swedish and Poland-Lithuanian alliance and counter-offensives: chronology, clfy/add |

|||

| Line 103: | Line 103: | ||

===Swedish and Poland-Lithuanian alliance and counter-offensives=== |

===Swedish and Poland-Lithuanian alliance and counter-offensives=== |

||

{{multiple image|direction=vertical|width=300|image1=Polacak, 1579.jpg|caption1=Siege of Polotsk, 1579, contemporary illustration|image2=Campaigns of Stefan Batory (1578-82).png|caption2=The campaigns of Stefan Batory: the red line marks the greatest extent of Russian occupation; the blue line the approximate border after the Treaty of Jam Zampolski}} |

{{multiple image|direction=vertical|width=300|image1=Polacak, 1579.jpg|caption1=Siege of Polotsk, 1579, contemporary illustration|image2=Campaigns of Stefan Batory (1578-82).png|caption2=The campaigns of Stefan Batory: the red line marks the greatest extent of Russian occupation; the blue line the approximate border after the Treaty of Jam Zampolski}} |

||

| ⚫ | John III and Stefan Batory allied against Ivan IV in December 1577 |

||

In 1576, the [[Principality of Transylvania (1571–1711)|Transylvanian prince]] [[Stephen Báthory of Poland|Stefan Batory]] became king of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania after a short and sharp civil war against the [[House of Habsburg|Habsburg]] [[Maximillian II, Holy Roman Emperor|Emperor Maximilian II]], following the double election of Batory's fiancèe [[Anna Jagiellon]] and Maximillian II in 1655.<ref>Stone (2001). pp.122–123</ref> Batory, ambitious to expel Ivan IV from Livonia, was constrained by the opposition of [[Danzig]] (Gdansk), which resisted Batory's accession with Danish support.<ref name=Stone123>Stone (1991), p. 123.</ref> Batory ended the ensuing [[Siege of Danzig (1577)|Danzig War]] of 1577 by conceding further autonomy rights to the city in turn for a payment of 200,000 [[Zloty#Kingdom_of_Poland_and_Polish-Lithuanian_Commonwealth|zloty]]; for another 200,000 zloty payment, he appointed [[House of Hohenzollern|Hohenzollern]] [[George Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach|George Frederick]] as adminstrator of [[Duchy of Prussia|Prussia]] and secured the latter's military support in the planned campaign against Russia.<ref name=Stone123/> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Swedish king John III and Stefan Batory allied against Ivan IV in December 1577. Already in November, Lithuanian forces had started an offensive from the south and captured Dünaburg.<ref name="Frost28">Frost (2000). p.28</ref> A Polish-Swedish force took the town and castle of Wenden in early 1578.<ref name="Peterson94">Peterson (2007). p.94</ref> Russian forces tried to re-take the town in February, but failed.<ref name=Frost28/> What followed was a Swedish offensive, targeting [[Pärnu|Pernau]] (Pärnu), Dorpat and [[Novgorod]] among others. In September, Ivan responded by sending in an army of 18,000 men, who re-captured [[Põltsamaa|Oberpahlen]] (Põltsamaa) from Sweden and then marched on Wenden.<ref name=Frost28/><ref name=Peterson94/> Upon their arrival at Wenden, the Russian army laid siege to the town, but was met by a relief force of around 6,000. In the ensuing [[Battles of Wenden (1577–1578)|Battle of Wenden]], Russian casualties were severe, and armaments and horses captured. Ivan IV was for the first time seriously defeated in Livonia.<ref name=Peterson94/> |

||

| ⚫ | Batory accelerated the formation of the [[hussars]], a new well-organised type of cavalry to replace the feudal levy. Similarly, he improved an already effective artillery system, and also recruited cossacks. Batory gathered 56,000 troops, 30,000 from Lithuania, together for his first assault on Russia at Polotsk, among a [[Livonian campaign of Stephen Báthory|wider campaign]]. The city fell on 30 August 1579; Ivan had kept Russia's reserves in Pskov and Novgorod to guard against a Swedish invasion. Batory then appointed a close ally and powerful member of his court, [[Jan Zamoyski]], to lead a force of 48,000, 25,000 from Lithuania, against the fortress of [[Velikie Luki]], capturing it on September 5, 1580.<ref name="stone126">Stone (2001), pp.126–7</ref> No other significant resistance was met, and garrisons such as Sokol, Velizh and Usvzat fell quickly.<ref>Solovyov (1791)</ref> The force then [[Siege of Pskov|besieged Pskov]] in 1581, a well-fortified and heavily defended fortress. Batory's financial support from the Polish parliament was also failing. Batory hoped to lure Russian forces in Livonia out into open field, but they did not so, and winter began to fall on Batory's men. Not realising that the Polish-Lithuanian advance was fading, Ivan signed the [[Treaty of Jam Zapolski]].<ref name="stone126"/> |

||

In 1581, a [[mercenary]] army hired by Sweden and commanded by [[Pontus de la Gardie]] re-captured the strategic city of Narva, a target of John III's campaigns, since it could be attacked by both land and sea, making use of Sweden's considerable fleet. Arguments over formal control in the long term hampered any alliance with Poland to aid in this endeavour, however, and an effort to take the city in 1579 failed.<ref name="Oakley34">Oakley (1993). p.34</ref> Following la Gardie's taking of the city, and in retaliation for previous Russian massacres,<ref>Solovyov (1791). p.881</ref> 7,000 Russians were killed according to [[Balthasar Russow|Russow]]'s contemporary chronicle.<ref>Frost (2000), p. 80, referring to Russow, B. (1578): ''Chronica der Provintz Lyfflandt'', p. 147.</ref> |

In 1581, a [[mercenary]] army hired by Sweden and commanded by [[Pontus de la Gardie]] re-captured the strategic city of Narva, a target of John III's campaigns, since it could be attacked by both land and sea, making use of Sweden's considerable fleet. Arguments over formal control in the long term hampered any alliance with Poland to aid in this endeavour, however, and an effort to take the city in 1579 failed.<ref name="Oakley34">Oakley (1993). p.34</ref> Following la Gardie's taking of the city, and in retaliation for previous Russian massacres,<ref>Solovyov (1791). p.881</ref> 7,000 Russians were killed according to [[Balthasar Russow|Russow]]'s contemporary chronicle.<ref>Frost (2000), p. 80, referring to Russow, B. (1578): ''Chronica der Provintz Lyfflandt'', p. 147.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:47, 18 January 2011

| Livonian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Siege of Narva by the Russians in 1558 by Boris Chorikov, 1836. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

(before 1569 the Polish-Lithuanian union) |

File:Russia01.gif Russia Kingdom of Livonia | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

File:PB Piast2 CoA.png Sigismund II |

File:Russia01.gif Ivan IV Magnus of Livonia | ||||||||

The Livonian War was fought between 1558–1583 for control of Old Livonia, the territory of present-day Estonia and Latvia. The Tsardom of Russia faced a variable coalition of Denmark–Norway, the Kingdom of Sweden and the union (later commonwealth) of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland.

The period 1558–1578 saw a period of Russian dominance in the region, marked by early successes at Dorpat (Tartu) and Narva and the dissolution of the Livonian Confederation. The Confederation's collapse brought Poland-Lithuania into conflict with Russia. Sweden and Denmark both intervened between 1559 and 1561, the former establishing the Duchy of Estonia under constant invasion from Russia, and the latter control of the old Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek placed under the control of Magnus of Holstein. Magnus would defect first to Ivan, forming the Duchy of Livonia and later the Kingdom of Livonia, and then to Poland-Lithuania. The war covered a period of instability with the oprichniki in Russia, and both it and Poland-Lithuania under threat from the Tatars in the south.

Stefan Batory, after becoming king of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania eventually turned the tide of the war, with successes between 1578 and 1581, including the joint Swedish–Poland-Lithuanian offensive at the Battle of Wenden. This was followed by a long campaign through Russia, before a long and difficult siege of Pskov. The war between Poland-Lithuania and Russia was concluded favourably for the former with the Truce of Jam Zapolski in 1582, with Russia losing all the holdings it had in Livonia and Polotsk to Poland-Lithuania. The year after Sweden and Russia signed the Truce of Plussa, Sweden gaining most of Ingria, and northern Livonia, keeping the Duchy of Estonia. Russia was left in humiliating defeat at the hands of western powers it considered its own equal or subordinate, and upon Ivan IV's death in 1584, Russia was left with no gains and became increasingly isolated from western politics and influence.[1]

Prelude

In the wake of the Livonian war, Livonia had a weak administration subject to internal rivalries, lacked a powerful defense or outside support, and was surrounded by monarchies pursuing expansive policies. This volatile region is described by Robert I. Frost as follows: "Racked with internal bickering and threatened by the political machinations of its neighbours, Livonia was in no state to resist an attack."[2] Or, as Robert Nisbet Bain put it: "Originally a compact, self-sufficiant, unconquerable military colony in the midst of savage and jarring barbarians, the Order had [...] sunk into a condition of confusion and decrepitude that tempted the greed of the three great monarchies – Sweden, Muscovy and Poland – which had, in the meantime, grown up around and now pressed hard on it. [...] Livonia was the apple of discord [...] for generations to come. Each of the three aimed at domination of the Baltic, and the first step towards the domination of the Baltic was the possession of Livonia."[3]

Livonia before the war

<div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting. | Type | Family | Handles wiki table code?† | Responsive/ Mobile suited | Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} | {{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} | {{col-end}} |

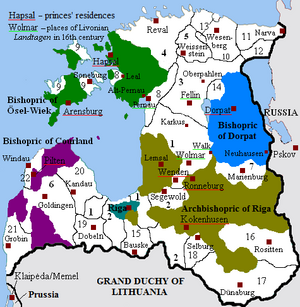

{| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.By the mid-16th century, Old Livonia was a region with a prospering economy,[4] organized in a de-centralized and religiously divided federation.[5] It consisted of territories of the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order, the prince-bishoprics of Dorpat, of Ösel-Wiek and of Courland, the Archbishopric of Riga and the city of Riga.[4][6] Besides Riga, the cities of Dorpat and Reval (Tallinn) as well as the knightly estates enjoyed privileges enabling them to act nearly independently.[6] The only common institutions of the Livonian estates were the regularly held common assemblies (landtag).[4] The political division was not only in administration, there were also persistent rivalries between the archbishop of Riga and the landmeister of the order for hegemony.[4][6] The order itself was divided since the Protestant Reformation had spread to Livonia in the 1520s – the transformation of Livonia into a Lutheran region was a slow, gradual process resisted by part of the order who in various degrees remained sympathetic to Roman Catholicism.[7]

The order's landmeister and gebietiger[nb 1] as well as the Livionian estates were all lesser nobles, who guarded their privileges and influence by preventing the creation of a powerful higher noble class.[8] This concept failed only in the archbishopric of Riga:[9] Albert (Albrecht) of Brandenburg-Ansbach, the former Prussian hochmeister who had secularised the southern Teutonic Order state and established himself as duke in Prussia in 1525 through the Treaty of Cracow, succeeded in installing his brother Wilhelm von Brandenburg as archbishop of Riga, with Christoph von Mecklenburg as his coadjutor.[10] Wilhelm and Christoph were to pursue Albert's interests in Livonia, among which was the establishment of a hereditary Livonian duchy styled after the Prussian model,[10] while at the same time the order agitated its re-establishment in Prussia ("Rekuperation"),[11] opposed secularization and the implementation of a hereditary duchy[9] and opposed making the landmeister office hereditary.[8]

Aspirations of Livonia's neighbours

At the time of the outbreak of the Livonian War, the Hanseatic League had already lost its monopoly in the profitable and prospering Baltic Sea trade.[12] While still participating and increasing sales, it shared the market with Western European mercenary fleets, most notably from the Dutch Seventeen Provinces.[12] The Hanseatic vessels were no match for contemporary warships,[13] and since the league was not able to maintain a larger navy,[14] it left its Livonian members Riga, Reval and its trading partner Narva without suitable protection.[15] The most powerful navy in the Baltic Sea was based in the Kingdom of Denmark, which controlled the entrance to the Baltic Sea,[13] raised the Sound Dues[14] and held the strategically important Baltic Sea islands of Bornholm and Gotland.[13]

The Kingdom of Sweden's access to the Baltic trade was severely limited by the long bar of Danish territories in the south and her lack of sufficient all-year ice-free ports.[16] Sweden however prospered due to the export of timber, iron and most notably copper, had a growing navy at her disposal[16] and was separated from the Livonian ports only by the Gulf of Finland.[3] Sweden sought to expand into this area already before the Livonian War, but the intervention of the Russian tsar temporarily stalled these efforts through the Russo-Swedish War of 1554–7, which culminated in the Treaty of Novgorod.[16]

In June 1556, Wilhelm appealed to Polish king Sigismund II for help against landmeister Wilhelm von Fürstenburg. Whilst there, however, von Fürstenburg successfully besieged the archbishop, and the landmeister's son killed Lancki, a Polish envoy. This was used as an excuse by Sigismund to invade the southern portion of Livonia with an excessive army of around 80,000. In September 1557, Sigismund reconciled the disagreeing parties by force at his camp in Pozvol, created a mutual defensive and offensive alliance, in the Treaty of Pozvol, primarily aimed at Russia.[17]

The Tsardom of Russia, which became Livonia's eastern neighbour by absorbing the principalities of Novgorod (1478) and Pskov (1510),[18] had grown stronger after annexing the khanates of Kazan (1552) and Astrakhan (1556). The conflict between Russia and the Western powers was exacerbated by Russia's isolation from sea trade. Nor could the tsar hire qualified labour in Europe. In 1547, Hans Schlitte, the agent of Tsar Ivan IV, employed handicraftsmen in Germany for work in Russia. However all these handicraftsmen were arrested in Lübeck at the request of Livonia.[19] The Hanseatic League ignored the new Ivangorod port built by Tsar Ivan on the eastern shore of the Narva River in 1550 and continued to trade with the ports owned by Livonia.[20] Tsar Ivan IV demanded that the Livonian Confederation pay about 6,000 marks to keep the Bishopric of Dorpat, based on the claim that every adult male had paid Pskov one mark whilst Pskov had been an independent state. They eventually promised to pay this sum to Ivan by 1557, but were dismissed from Moscow when they failed to do so. Ivan continued to point out that the existence of the order required his goodwill, and was quick to threaten them with military force if necessary.[21] Ivan aimed to establish a corridor between the Baltic and the new territories on the Caspian Sea for if Russia were to embark on open conflict with major western powers, it would need more sophisticated weaponry to be imported.[21]

The war's beginnings

Russian and Polish-Lithuanian intervention, dissolution of the Livonian Order

When the Livonian Confederation turned to the Polish-Lithuanian union for protection in the Treaty of Pozvol, this was regarded by Ivan IV as casus belli.[22] In 1558, he reacted with the invasion of Livonia. Many Livonian fortresses surrendered without resistance to the Russian troops, who took Dorpat in May, Narva in July,[23] and laid siege to Reval. Reenforced by 1,200 landsknechte, 100 gunners and ammunition from Germany, Livonian forces successfully retook Wesenberg (Rakvere) along with some other fortresses and raided Russian territory, yet Dorpat, Narva and many lesser fortresses remained in Russian hands.[24] The initial Russian advance was led the Khan of Kasimov, with two other Tartar princes. Its force included Russian boiars, Tartar and pomest'e cavalry and cossacks.[25] Cossacks at this time were mostly armed foot soldiers.[26] The goal of Tsar Ivan was to gain vital access to the Baltic Sea.[25]

Prompted by the Russian invasion, landmeister Wilhelm von Fürstenburg fled to Poland-Lithuania, and was replaced by Gotthard Kettler. In June 1559, the estates of Livonia came under Polish-Lithuanian protection by the first treaty of Vilnius (Vilna). The Polish sejm refused to agree to the treaty, believing it to be a matter affecting only the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[17] In January 1560, Sigismund sent an ambassador, Martin Volodkov, to the court of Ivan IV in Moscow in an attempt to stop the rampage the Russian cavalry were carrying out in rural part of Livonia.[27]

Ivan IV gained ground in further campaigns during the years 1559 and 1560.[24] Between these campaigns, Russian and Livonian forces signed a six-month truce in 1559 while Russia fought in the Crimean War. Russian successes followed similar patterns: a multitude of small campaigns, with sieges where musketmen played a key role in destroying wooden defences and with the effective use of artillery.[25] Ivan IV's forces took important fortresses like Fellin (Viljandi), yet lacked the means to gain the major cities Riga, Reval or Pernau.[24] After the Battle of Ērģeme (Ermes) of August 1560, where the Livonian knights suffered a disastrous defeat against Ivan IV's forces, the weakened Livonian Order was dissolved by the second Treaty of Vilnius (1561). The order assigned its lands, secularised as Duchy of Livonia and Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Kettler became the first duke of Courland, in doing so converting to Lutheranism.[17]

Part of the Lithuanian nobles opposed the Polish-Lithuanian union, and offered the Lithuanian crown to Ivan IV.[28] Ivan IV publicly advertised this option, either because he took the offer seriously, or because he needed time to strengthen his Livonian troops.[29] Throughout 1561, a Russo-Lithuanian truce was respected by both sides, which was scheduled to expire in 1562.[29]

Danish and Swedish interventions

In return for a loan and guarantee of its protection, Bishop Johann von Münchhausen signed a treaty on the 26 September 1559 giving Frederick II of Denmark the right to nominate the bishop of Ösel–Wiek, an act which amounted to the sale of these territories for 30,000 thalers. The sale was recognised by Poland-Lithuania in 1571.[30] Frederick II nominated his brother, Duke Magnus of Holstein, who took possession in April 1560, prompting Sweden to once again attempt to mediate a peace in the region, lest Danish efforts create more insecurity for Sweden.[31] Magnus at once pursued own interests, purchased the Bishopric of Courland without Frederick's consent and tried to expand into Harrien–Wierland (Harju and Virumaa), bringing him into direct conflict with Eric XIV, Swedish king since 1560.[24]

The city council of Reval turned to Eric XIV for help against other troops. In 1561, Swedish forces arrived and the noble corporations of Harrien–Wierland and Jerwen (Järva) yielded to Sweden, forming the Duchy of Estonia.[32] Sweden hoped to establish itself on the eastern side of the Baltic, which was dominated by Denmark and thus control trade to Russia. This helped to precipitate the Northern Seven Years' War.[33] Already in 1561, Frederick II had protested against Swedish presence in Reval, claiming historical rights relating to Danish Estonia.[29] When Erik XIV's forces seized Pernau in June 1562 and his diplomats tried to arrange Swedish protection for Riga, this brought him in conflict with Sigismund.[29]

Sigismund maintained close relations to Erik XIV's brother, John, Duke of Finland (later John III). In October 1562, John married Sigismund's sister, Catherine. While Erik XIV had approved the marriage, he was upset when John lent Sigismund 120,000 riksdalers and received seven Livonian castles as security. This incident led to John's capture and imprisonment in August 1563 on Erik XIV's behalf, whereupon Sigismund allied with Denmark and Lübeck against Erik XIV in October.[29]

The war from 1562 to 1570

While the initial war years were characterized by intensive fighting, a period of low-intensity warfare began in 1562, lasting until 1570 when fighting intensified again.[34] Denmark, Sweden and to some extend Poland-Lithuania were occupied with the Nordic Seven Years' War (1563-1570) in the Western Baltic,[35] "yet Livonia remained an important theatre of conflict" (Frost).[24] Both Ivan IV and Eric XIV showed signs of mental disorder.[36] Ivan IV and his oprichina turned against part of the tsardom's nobility and people starting in 1565, leaving Russia in a state of political chaos and civil war.[29]

Russian war with Poland-Lithuania

The Russo-Lithuanian truce expired in 1562, and Ivan IV rejected Sigismund's offer for an extension.[29] The tsar had used the truce to build up his forces in Livonia, and invaded Lithuania.[29] His forces took Vitebsk and, after a series of border clashes, Polotsk in 1563.[29] Lithuanian victories came at the Ula (Ūla) river in 1564 and at Czasniki (Chashniki) in 1564[29] and 1567, a period of intermittent conflict between the two sides; Ivan continued to gain ground among the towns and villages of central Livonia but was held at the coast by the other powers.[37] The defeats of Ula and Czasniki, along with the defection of Andrey Kurbsky led Ivan IV to move his capital to the Alexandrov Kremlin and have the perceived opposition against him repressed by his oprichniki.[29]

A "grand" party left Lithuania for Moscow in May 1566, where they were received by the Tsar with the usual banquet. Lithuania was prepared to split Livonia with Russia, with a view to a joint offensive to push Sweden out of the area. This was seen as a sign of weakness by Russian diplomats, who therefore suggested that Russia should take the whole of Livonia, including Riga, through the ceding of Courland in southern Livonia and Polotsk on the Lithuanian-Russian border. It was the transfer of Riga, and the surrounding entrance to the River Dvina that troubled the Lithuanians, since much of their trade depended on safe passage through it; they had already built fortifications to protect it. Ivan expanded his demands in July, calling for Ösel in addition to Dorpat and Narva. No agreement was forthcoming, and after a ten-day break in negotiations during which time various Russian meetings were held (including the zemsky sobor, the Assembly of the Land) to discuss the issues at stake. Within the Assembly, the church's representative stressed the need to 'keep' Riga (it not yet having been conquered); the Boyars were less keen on an overall peace with Poland-Lithuania.[38]

In 1569, the Treaty of Lublin unified Poland and Lithuania into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and with it Lithuania's Livonian territories. In 1572, Sigimund II, the Commonwealth's first king, died, leaving the Polish throne without a clear successor for the first time since 1382. Much of Lithuania, still annoyed at the permanent union with Poland, wished to elect Ivan IV to the Polish-Lithuanian throne, in the hope of preventing further Russian raids into Lithuania. The electors rejected this, instead electing Henry of Valois (Henryk Walezy), brother of King Charles IX of France.[39]

Russian war with Sweden

Eric XIV of Sweden was overthrown in 1568 after he killed several nobles in the Sture Murders (Sturemorden) of 1567, and was replaced by his half-brother John III. [40] Ivan IV had requested the return of John's wife, Catherine Jagellonica to Russia, supposedly fearing John's death whilst incarcerated by his brother, and in July 1569 John sent a party to Russia, lead by Paul Juusten, Bishop of Åbo. The bishop arrived in Novgorod in September, following the arrival in Moscow of the ambassadors sent to Sweden in 1567 by Ivan to retrieve Catherine. Ivan refused to meet with the party himself, forcing them to negotiate instead with the Governor of Novgorod. John was not a hereditary king, having replaced his half-brother by force and Ivan was troubled by the attack on his own ambassador, Vorontsov. The Tsar requested that Swedish envoys should greet the governor as 'the brother of their king', but Juusten refused to do so. The Governor ordered that the Swedish party be attacked, their clothes and money taken, they be deprived of their food and drink and that they be paraded naked through the streets; furthermore, they were to be moved to Moscow. Fortunately for the Swedes, they were being transferred at the same time Ivan and his oprichniki were on their way to assault Novgorod.[41] On return to Moscow in May 1570, Ivan refused to meet the Swedish party, and with the signing of a three-year truce in June 1570 no longer feared war with Poland-Lithuania as a possible reprisal for his actions against the Swedish diplomats. They were finally met by Ivan Viskovaty and Andrei Vasilev (both of whom would shortly be executed); Russia considered the return of Catherine to be a precondition of any deal. Whether she was to bcome Ivan's next wife, a mistress or merely a captive for political gain was not made clear. The Swedes agreed to meet in Novgorod to discuss this. Writing to John in August 1572, Ivan expands on his belief that John's position was under threat, saying that he has been told he was besieged in Stockholm, and that his brother Eric was advancing on him.[41]

The Swedes' detention in Russia, at Morum, continued. Eventually, Ivan made several demands of Sweden in compensation for the attack on Vorontsov. According to Juusten, these were to abandon their claim to Reval; to provide two or three hundred cavalry when required; to pay 10,000 thaler in direct compensation; to surrender Finish silver mines near the border with Russia and to allow the Tsar to style himself "Lord of Sweden". Russian records claim that Sweden was to produce a wooden set of the Swedish coat of arms, to be incorporated into the Russia, thus confirming their subjectivity. After making up with the Swedish envoys, he promised to let them depart along with an ultimatum that Sweden should cede its part of Livonia, or else there would be war. Juusten was left behind. John rejected Ivan's demands, and thus war broke out anew.[42]

Impact of the Northern Seven Years' War

Quarrels between Denmark and Sweden had led to the contemporary Northern Seven Years' War in 1563, concluded in 1570 by the Treaty of Stettin.[43] The war was primarily fought in western and southern Scandinavia, involving important naval battles in the Baltic.[43] When in 1565 Danish-held Varberg surrendered to Swedish forces, 150 mercenaries were excepted from a massacre of the garrison when they entered from Danish into Swedish service.[44] Among them was Pontus de la Gardie,[44] who became an important Swedish commander in the Livonian War thereafter.[45] Another incident affecting Livonia was the naval campaign of Danish admiral Peter or Per Munck, who bombarded Swedish Reval from sea in July 1569.[46]

Under the Treaty of Stettin, Sweden agreed to turn over her possessions in Livonia for a payment by Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II.[47] However, Maximilian failed pay the compensation promised to Sweden, and therefore lost his influence on the Baltic affairs. The terms of the treaty regarding Livonia were ignored, and thus the Livonian War continued.[48] From Ivan's point of view, this merely enabled the powers involved to come to some alliance against him, now no longer fighting each other.[41]

From 1570 to 1577: Russian dominance and Kingdom of Livonia

John III (King of Sweden) faced a Russian offensive on his positions in Estonia during the early 1570s.[49] Reval withstood a Russian siege in 1570 and 1571,[50] but several smaller towns were taken by Russian forces. The Russian advance was concluded with the sacking of Weissenstein (Paide) in 1573. After the capture, the Russian forces roasted alive some of the leaders of Weissenstein's Swedish garrison, including its commander, triggering John to mount a retaliatory campaign centred on Wesenberg.[49] In November 1573, the army left for Wesenberg,[51] under the overall command of Klas Åkesson Tott (the Elder) and field command of Pontus de la Gardie.[49]

This counter-offensive was stalled in the siege of Wesenberg in 1574 when German and Scottish units of the Swedish army turned against each other.[49] The failure of the siege has also been put down to the bitter winter conditions and the difficulty faced, particularly by infantry, in fighting in them.[52] The war in Livonia therefore became a greater burden for Sweden and for Denmark. However, Magnus' efforts to besiege Reval, then controlled by Sweden, were failing. Support from neither Ivan nor from Magnus' brother, Frederick II of Denmark was forthcoming; the former on account of responsibilities elsewhere and the latter perhaps from the newly-found Swedish-Danish unity, and unwillingess to invade Livonia on behalf of Magnus, whose state was a vassal of Russia.[41]

Meanwhile, the Crimean Tatars devastated Russian territories and burnt down Moscow in the Russo-Crimean Wars. Drought and epidemics had fatally affected the economy, and oprichnina had thoroughly disrupted the government. Following the defeat of Crimean and Nogai forces in 1572, the oprichnina was wound down and thus the way Russian armies were formed also changed.[53] Ivan IV had introduced a new strategy, relying on tens of thousands of native troops, cossacks and tartars, instead of a few thousand skilled troops and mercenaries, as practiced by his adversaries. Swedish forces were sieged in Reval, Danish Estonia was raided, and so was central Livonia as far as Dünaburg (Daugavpils), formally under Polish-Lithuanian superiority since the Treaty of Vilnius in 1561.[49] The conquered territories submitted to Ivan or his vassal, Magnus,[49] declared monarch of the Kingdom of Livonia in 1570.[40]

The year of 1576 marked the height of Ivan's campaign, and another 30,000 Russian soldiers crossed into Livonia in 1577.[40] Magnus had fallen into disgrace when he defected from Ivan IV during the same year,[54] and started to subordinate castles without consulting the tsar. When Kokenhusen (Koknese) submitted to Magnus to avoid fighting Ivan IV's army, the tsar sacked it and executed its German commanders.[40] The campaign then focussed on Wenden (Cēsis, Võnnu), "the heart of Livonia", which as the former capital of the Livonian Order was not only of strategic importance, but also a symbol for Livonia itself.[49]

The final war years

Swedish and Poland-Lithuanian alliance and counter-offensives

In 1576, the Transylvanian prince Stefan Batory became king of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania after a short and sharp civil war against the Habsburg Emperor Maximilian II, following the double election of Batory's fiancèe Anna Jagiellon and Maximillian II in 1655.[55] Batory, ambitious to expel Ivan IV from Livonia, was constrained by the opposition of Danzig (Gdansk), which resisted Batory's accession with Danish support.[56] Batory ended the ensuing Danzig War of 1577 by conceding further autonomy rights to the city in turn for a payment of 200,000 zloty; for another 200,000 zloty payment, he appointed Hohenzollern George Frederick as adminstrator of Prussia and secured the latter's military support in the planned campaign against Russia.[56]

Swedish king John III and Stefan Batory allied against Ivan IV in December 1577. Already in November, Lithuanian forces had started an offensive from the south and captured Dünaburg.[57] A Polish-Swedish force took the town and castle of Wenden in early 1578.[58] Russian forces tried to re-take the town in February, but failed.[57] What followed was a Swedish offensive, targeting Pernau (Pärnu), Dorpat and Novgorod among others. In September, Ivan responded by sending in an army of 18,000 men, who re-captured Oberpahlen (Põltsamaa) from Sweden and then marched on Wenden.[57][58] Upon their arrival at Wenden, the Russian army laid siege to the town, but was met by a relief force of around 6,000. In the ensuing Battle of Wenden, Russian casualties were severe, and armaments and horses captured. Ivan IV was for the first time seriously defeated in Livonia.[58]

Batory accelerated the formation of the hussars, a new well-organised type of cavalry to replace the feudal levy. Similarly, he improved an already effective artillery system, and also recruited cossacks. Batory gathered 56,000 troops, 30,000 from Lithuania, together for his first assault on Russia at Polotsk, among a wider campaign. The city fell on 30 August 1579; Ivan had kept Russia's reserves in Pskov and Novgorod to guard against a Swedish invasion. Batory then appointed a close ally and powerful member of his court, Jan Zamoyski, to lead a force of 48,000, 25,000 from Lithuania, against the fortress of Velikie Luki, capturing it on September 5, 1580.[59] No other significant resistance was met, and garrisons such as Sokol, Velizh and Usvzat fell quickly.[60] The force then besieged Pskov in 1581, a well-fortified and heavily defended fortress. Batory's financial support from the Polish parliament was also failing. Batory hoped to lure Russian forces in Livonia out into open field, but they did not so, and winter began to fall on Batory's men. Not realising that the Polish-Lithuanian advance was fading, Ivan signed the Treaty of Jam Zapolski.[59]

In 1581, a mercenary army hired by Sweden and commanded by Pontus de la Gardie re-captured the strategic city of Narva, a target of John III's campaigns, since it could be attacked by both land and sea, making use of Sweden's considerable fleet. Arguments over formal control in the long term hampered any alliance with Poland to aid in this endeavour, however, and an effort to take the city in 1579 failed.[1] Following la Gardie's taking of the city, and in retaliation for previous Russian massacres,[61] 7,000 Russians were killed according to Russow's contemporary chronicle.[62]

Truces of Jam Zapolski and Plussa

These developments led to the signing of the peace Truce of Jam Zapolski in 1582 between Russia and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, lead in negotiations by Jesuit papal legate Antonio Possevino. It was a humiliation for the Tsar, in part because he was the one requesting it. Russia would surrender to the Polish-Lithuanian Confederation all areas in Livonia it still held and the city of Dorpat; Polotsk would be kept under the confederation's control. In return, Velike Luki would be returned from Batory's control to Russia. Any conquests made from Sweden could be kept, with Narva being specifically mentioned. Possevino made a half-hearted attempt to get John III's wishes discussed, but this was vetoed by the Tsar, probably in alignment with Batory.[63] The armistice, which fell short of a full peace arrangement, was to last ten years; it was renewed twice, in 1591 and 1601.[64]

The following year, the war ended when the Tsar concluded the Truce of Plussa (Plyussa, Pljussa, Plusa) with Sweden, relinquishing most of Ingria and leaving Narva and Ivangorod under Swedish control.[65] The Russo-Swedish truce was scheduled to last three years, but was later extended until 1590.[65]

Aftermath

South of the Düna (Dvina) river, the post-war Duchy of Courland and Semigallia experienced a period of political stability based on the Treaty of Vilnius, which only in 1617 was modified by the Formula regiminis and Statuta Curlandiæ, granting the indigenous nobles additional rights at the duke's expense.[66]

North of the Düna, Stefan Batory denied the inhabitants of the Duchy of Livonia many privileges granted by Sigismund II Augustus in 1561, since he regarded the territories re-gained at Jam Zapolski as his war booty.[67] The traditional Baltic German administration and jurisdiction was gradually impaired by the establishment of voivodeships, the appointment of Royal officials, and the replacement of German with Polish as administrative language.[68] Riga's privileges had already been reduced by the Treaty of Drohiczyn in 1581.[69] The Duchy of Livonia was subjected to counter-reformation by part of the local clergy and the Jesuits of Riga and Dorpat, who focussed on the rural Latvians and Estonians whom they regarded as excluded from the privileges granted to the German Livonian estates.[70] Batory assisted by granting revenues and estates confiscated from Protestants to the Roman Catholic Church and by initiating a largely unsuccessful recruitment campaign for Catholic colonists.[71] These measures however failed to achieve a conversion of the Livonian population, and further alienated the Livonian estates from Poland-Lithuania.[71]

In 1590, the Russo-Swedish truce of Plussa expired and fighting resumed.[65] The Russo-Swedish War of 1590–5 was ended by the Treaty of Teusina (Tyavzino, Tyavzin), in which Sweden had to cede Ingria and Kexholm to Russia.[72] During the same period, the Swedish-Polish alliance began to crumble when the Polish king and grand duke of Lithuania Sigismund III, who as son of John III of Sweden (died 1592) and Catherine Jagellonica, was the successor to the Swedish throne, met with the resistance of a party led by his uncle, Charles of Södermanland (later Charles IX), who claimed regency in Sweden for himself.[72] The result was a civil war in Sweden, starting in 1597, and the war against Sigismund from 1598 to 1599, which ended with the deposition of Sigismund by the Swedish riksdag.[72]

In 1600, the conflict spread to Livonia: Sigismund tried to incorporate Swedish Estonia into the Duchy of Livonia, whereupon the local nobles turned to Charles for protection.[73] Charles expelled the Polish forces from Estonia[73] and invaded the Livonian duchy, starting a series of Polish–Swedish wars.[74] At the same time, Russia was in a state of civil war as the Russian throne was vacant and none of the many claimants prevailed (called the "Time of Troubles"); this conflict became entangled with the Livonian campaigns when Swedish and Polish-Lithuanian forces intervened on opposite sides, the latter starting the Polish–Muscovite War.[74] Charles IX's forces were expelled from Livonia[75] after major setbacks at the battles of Kircholm (1605)[76] and Klushino (1610),[75] his successor Gustavus Adolphus however re-took Ingria and Kexholm in the Ingrian War (formally ceded in the Treaty of Stolbovo, 1617)[75] as well as the bulk of the Duchy of Livonia: in 1617, when Sweden had recovered from the Kalmar War with Denmark, several Livonian towns were captured, yet only Pernau could be kept after a Polish-Lithuanian counter-offensive;[77] a second campaign however which started with the capture of Riga in 1621 expelled the Polish-Lithuanian forces from most of Livonia, where the dominion of Swedish Livonia was created.[73] After Swedish forces then advanced through Royal Prussia, Poland-Lithuania accepted the Swedish gains in Livonia in the Treaty of Altmark in 1629.[78]

Danish Estonia was ceded to Sweden in the Treaty of Brömsebro (1645), which ended the Torstenson War, a theatre of the Thirty Years' War.[79] Only in 1710 the situation changed again, when Estonia and Livonia capitulated to Russia during the Great Northern War, formalized in the Treaty of Nystad (1721).[80]

Notes

- ^ The order was led by a hochmeister, an office since 1525 executed by the deutschmeister responsible for the bailiwicks in the Holy Roman Empire; the order's organisation in Livonia was led by a circle of gebietigers headed by a landmeister elected from their midst.

Sources

References

- ^ a b Oakley (1993). p.34

- ^ Frost (2000), p. 2.

- ^ a b Bain (1971), p. 84.

- ^ a b c d Rabe (1989), p. 306.

- ^ Dybas (2009), p. 193.

- ^ a b c Bülow (2003), p. 73.

- ^ Kreem (2006), p. 46, pp. 51-53.

- ^ a b Kreem (2006), p. 50.

- ^ a b Kreem (2006), p. 51.

- ^ a b Körber (1998), p. 26.

- ^ Kreem (2006), p. 46

- ^ a b Frost (2000), p. 3.

- ^ a b c Frost (2000), p. 5.

- ^ a b Frost (2000), p. 6.

- ^ Frost (2000), p. 4.

- ^ a b c Frost (2000), p. 7.

- ^ a b c Bain (1971). p.84

- ^ Frost (2000), p. 10.

- ^ Karamzin (1826).

- ^ "The Full Collection of Russian Annals", vol. 13, SPb, 1904

- ^ a b Madaringa (2006). p.124

- ^ De Madariaga (2006). p.127

- ^ Frost (2000), p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e Frost (2000), p. 25.

- ^ a b c Stevens (2007). p.85

- ^ Frost (2000) p.50

- ^ Bain (1971). p.117

- ^ Frost (2000), pp. 25-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Frost (2000), p. 26.

- ^ Journal of central European affairs. Vol. 5. 1945. p. 135.

- ^ Bain (2006). p.56

- ^ Eriksson (2007). pp.45–46

- ^ Elliott (2000). p.14

- ^ Frost (2000), p. 77.

- ^ Frost (2000), pp. 30ff.

- ^ Frost (2000), pp. 26-27.

- ^ Bain (1971). p.123

- ^ De Madariaga (2006). pp.195–203

- ^ Bain (1971). pp.90–1

- ^ a b c d Frost (2000), p. 27. Cite error: The named reference "Frost27" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d De Madringa (2006). pp.261–264

- ^ De Madariaga (2006). pp.217–227

- ^ a b Frost (2000), pp. 29-37.

- ^ a b Frost (2000), p. 76

- ^ Frost (2000), pp. 44, 51.

- ^ Frost (2000), p. 36.

- ^ Nordstrom (2000). p.36

- ^ Peterson (2007). p.90

- ^ a b c d e f g Peterson (2007). pp. 91–93

- ^ Black (1996).

- ^ Fisher (1907).

- ^ Frost (2000).

- ^ De Madariaga (2006). pp.277–8

- ^ Oakley (1993). p.37

- ^ Stone (2001). pp.122–123

- ^ a b Stone (1991), p. 123.

- ^ a b c Frost (2000). p.28

- ^ a b c Peterson (2007). p.94

- ^ a b Stone (2001), pp.126–7

- ^ Solovyov (1791)

- ^ Solovyov (1791). p.881

- ^ Frost (2000), p. 80, referring to Russow, B. (1578): Chronica der Provintz Lyfflandt, p. 147.

- ^ Roberts (1968). p.264

- ^ Wernham (1968). p.393

- ^ a b c Frost (2000), p. 44.

- ^ Dybaś (2006), p. 110

- ^ Dybaś (2006), p. 109

- ^ Tuchtenhagen (2005), p. 36

- ^ Tuchtenhagen (2005), p. 37

- ^ Kahle (1984), p. 17

- ^ a b Tuchtenhagen (2005), p. 38

- ^ a b c Frost (2000), p. 45.

- ^ a b c Steinke (2009), p. 120

- ^ a b Frost (2000), p. 46.

- ^ a b c Frost (2000), p. 47.

- ^ Frost (2000), pp. 62, 64ff.

- ^ Frost (2000), p. 102.

- ^ Frost (2000), p. 103.

- ^ Frost (2000), pp. 103-104.

- ^ Kahle (1984), p. 18

Bibliography

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1905 (reprinted 2006)). Scandinavia: a Political History of Denmark, Norway and Sweden from 1513 to 1900. Adamant Media Corp. ISBN 0543938999. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Bain, Robert Nisbet (1908 (reprinted 1971)). Slavonic Europe. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Check date values in:|year=(help) - Black, Jeremy (1996). Warfare. Renaissance to revolution, 1492–1792. Cambridge Illustrated Atlases. Vol. II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521470331.

- Bülow, Werner (2003). Als die Bayern Bonn eroberten. Aus der Erlebniswelt einer Generation im Europa des 16. Jahrhunderts (in German). UTZ. ISBN 3831602441.

- Dybaś, Bogusław (2006). "Livland und Polen-Litauen nach dem Frieden von Oliva (1660)". In Willoweit, Dietmar; Lemberg, Hans (ed.). Reiche und Territorien in Ostmitteleuropa. Historische Beziehungen und politische Herrschaftslegitimation. Völker, Staaten und Kulturen in Ostmitteleuropa (in German). Vol. 2. Munich: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. pp. 51–72. ISBN 3486578391.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Dybaś, Bogusław (2009). "Zwischen Warschau und Dünaburg. Die adligen Würdenträger in den livländischen Gebieten der Polnisch-Litauischen Republik". In North, Michael (ed.). Kultureller Austausch: Bilanz und Perspektiven der Frühneuzeitforschung (in German). Köln/Weimar: Böhlau. pp. 193&nfash, 202. ISBN 3412203335.

- Elliott, John Huxtable (2000). Europe divided, 1559–1598. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780631217800.

- Eriksson, Bo (2007). Lützen 1632 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Norstedts Pocket. ISBN 9789172637900.

- Fischer, Ernst Ludwig aka Thomas A. Fisher (pseud.) (1907). The Scots in Sweden; being a contribution towards the history of the Scot abroad. BiblioBazaar, LLC.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Frost, Robert I. (2000). The Northern Wars. Pearson Education. ISBN 0582064295.

- Kahle, Wilhelm (1984). "Die Bedeutung der Confessio Augustana für die Kirche im Osten". In Hauptmann, Peter (ed.). Studien zur osteuropäischen Kirchengeschichte und Kirchenkunde. Kirche im Osten (in German). Vol. 27. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 9–35. ISBN 3525563825.

- Karamzin, Nikolai Mikhailovich (1826). The History of the Russian State. Vol. VIII.

- Kreem, Juhan (2006). "Der Deutsche Orden und die Reformation in Livland". In Mol, Johannes A.; Militzer, Klaus; Nicholson, Helen J. (eds.). The military orders and the Reformation. Choices, state building, and the weight of tradition (in German). Uitgeverij Verloren. pp. 43–58. ISBN 9065509135.

- Körber, Esther-Beate (1998). Öffentlichkeiten der frühen Neuzeit. Teilnehmer, Formen, Institutionen und Entscheidungen öffentlicher Kommunikation im Herzogtum Preussen von 1525 bis 1618 (in German). de Gruyter. ISBN 3110156008.

- De Madariaga, Isabel (2006). Ivan the Terrible. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300119732. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- Nordstrom, Byron J. (2000). Scandinavia Since 1500. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816620982.

- Oakley, Steward (1992). War and peace in the Baltic, 1560–1790. War in Context. Abingdon – New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415024722. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- Peterson, Gary Dean (2007). Warrior kings of Sweden. The rise of an empire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. McFarland. ISBN 0786428732.

- Rabe, Horst (1989). Reich und Glaubensspaltung. Deutschland 1500–1600. Neue deutsche Geschichte (in German). Vol. 4. Beck. ISBN 3406308163.

- Roberts, Michael (1968). The Early Vasas: A History of Sweden, 1523–1611. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1001296982. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- Solovyov, Sergey (1791). History of Russia from the Earliest Times (in Russian). Vol. VI. ISBN 5170021429. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- Steinke, Dimitri (2009). Die Zivilrechtsordnungen des Baltikums unter dem Einfluss ausländischer, insbesondere deutscher Rechtsquellen. Osnabrücker Schriften zur Rechtsgeschichte (in German). Vol. 16. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 389971573X.

- Stevens, Carol Belkin (2007). Russia's wars of emergence, 1460–1730. Pearson Education. ISBN 9780582218918. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- Stone, Daniel (2001). The Polish-Lithuanian state, 1386–1795. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295980931. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- Tuchtenhagen, Ralph (2005). Geschichte der baltischen Länder. Beck'sche Reihe (in German). Vol. 2355. C.H.Beck. ISBN 3406508553.

- Wernham, Richard Bruce (1968). The new Cambridge modern history: The Counter-Reformation and price revolution, 1559–1610. Cambridge University Press Archive.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian). 1906.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Livländischer Krieg von 1554-1566. In: Mitteilungen aus dem Gebiete der Geschichte Liv-, Est- und Kurlands (edited by Gesellschaft für Geschichte und Altertumskunde der russischen Ostsee-Provinzen). Riga/Leipzig 1840, pp. 94-127, in German (Online)