Mel Gibson

Mel Gibson | |

|---|---|

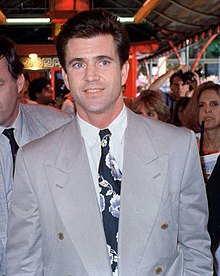

at the 1990 Air America premiere | |

| Born | Mel Colm-Cille Gerard Gibson |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, film director, film producer, screenwriter |

| Years active | 1976–present |

| Spouse |

Robyn Moore (m. 1980) |

Mel Colm-Cille Gerard Gibson, AO (born January 3, 1956) is an American Australian actor, film director, producer and screenwriter. Born in Peekskill, New York, Gibson moved with his parents to Sydney when he was 12 years old and later studied acting at the Australian National Institute of Dramatic Art.

After appearing in the Mad Max and Lethal Weapon series, Gibson went on to direct and star in the Academy Award-winning Braveheart. Gibson's direction of Braveheart made him the sixth actor-turned-filmmaker to receive an Academy Award for Best Director.[1] In 2004, he directed and produced The Passion of the Christ, a controversial[2] but successful[3] film that portrayed the last hours of the life of Jesus Christ. The movies he has acted in have grossed more than two billion dollars in the U.S. alone.[4]

Early life

Gibson was born in Peekskill, New York, the sixth of eleven children, and the second son of Hutton Gibson and Irish-born Anne Patricia (née Reilly, died 1990).[5][6] His paternal grandmother was the Australian opera soprano, Eva Mylott (1875–1920).[7] One of Gibson's younger brothers, Donal, is also an actor. Gibson's first name comes from Saint Mel, fifth-century Irish saint, and founder of Gibson's mother's native diocese, Ardagh, while his second name, Colm-Cille,[8] is shared by an Irish saint[9] and is the name of the parish in County Longford where Gibson's mother was born and raised. Because of his mother, Gibson holds dual Irish and American citizenship.[10]

Soon after being awarded $145,000 in a work-related-injury lawsuit against New York Central Railroad on February 14, 1968, Hutton Gibson relocated his family to Sydney, Australia.[11] Gibson was 12 years old at the time. The move to Hutton's mother's native Australia was for economic reasons, and because Hutton thought the Australian military would reject his oldest son for the Vietnam War draft.[12]

Gibson was educated by members of the Congregation of Christian Brothers at St. Leo's Catholic College in Wahroonga, New South Wales, during his high school years.[13][14]

Career

Gibson gained very favorable notices from film critics when he first entered the cinematic scene, as well as comparisons to several classic movie stars. In 1982, Vincent Canby wrote that “Mr. Gibson recalls the young Steve McQueen… I can't define "star quality," but whatever it is, Mr. Gibson has it.”[15] Gibson has also been likened to “a combination Clark Gable and Humphrey Bogart.”[16] Gibson's physical appearance made him a natural for leading male roles in action projects such as the "Mad Max" series of films, Peter Weir's Gallipoli, and the "Lethal Weapon" series of films. Later, Gibson expanded into a variety of acting projects including human dramas such as Hamlet, and comedic roles such as those in Maverick and What Women Want. His most artistic and financial success came with films where he expanded beyond acting into directing and producing, such as 1993's The Man Without a Face, 1995's Braveheart, 2000's The Patriot (acted only), 2004's The Passion of the Christ and 2006's Apocalypto. Actor Sean Connery once suggested Gibson should play the next James Bond to Connery's M. Gibson turned down the role, reportedly because he feared being typecast.[17]

Stage

Gibson studied at the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) in Sydney. The students at NIDA were classically trained in the British-theater tradition rather than in preparation for screen acting.[18] As students, Gibson and actress Judy Davis played the leads in Romeo and Juliet, and Gibson played the role of Queen Titania in an experimental production of A Midsummer Night's Dream.[19] After graduation in 1977, Gibson immediately began work on the filming of Mad Max, but continued to work as a stage actor, and joined the State Theatre Company of South Australia in Adelaide. Gibson’s theatrical credits include the character Estragon (opposite Geoffrey Rush) in Waiting for Godot, and the role of Biff Loman in a 1982 production of Death of a Salesman in Sydney. Gibson’s most recent theatrical performance, opposite Sissy Spacek, was the 1993 production of Love Letters by A. R. Gurney, in Telluride, Colorado.[20]

Australian television and cinema

While a student at NIDA, Gibson made his film debut in the 1977 film Summer City, for which he was paid $250. Gibson also played a mentally-slow youth in Tim, which earned him the Australian Film Institute Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role. The release of Mad Max in 1979 brought Gibson to mainstream attention.

During this period Gibson also appeared in Australian television series guest roles on programs The Sullivans, Cop Shop (in 1980), and in the pilot episode of Punishment (produced in 1980, screened 1981).

Gibson joined the cast of the World War II action film Attack Force Z, which was not released until 1982 when Gibson had become a bigger star. Director Peter Weir cast Gibson as one of the leads in the critically-acclaimed World War I drama Gallipoli, which earned Gibson another Best Actor Award from the Australian Film Institute. The film Gallipoli also helped to earn Gibson the reputation of a serious, versatile actor and gained him the Hollywood agent Ed Limato. The sequel Mad Max 2 was his first hit in America (released as The Road Warrior). In 1982 Gibson again attracted critical acclaim in Peter Weir’s romantic thriller The Year of Living Dangerously. Following a year hiatus from film acting after the birth of his twin sons, Gibson took on the role of Fletcher Christian in The Bounty in 1984. Playing Max Rockatansky for the third time in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome in 1985 earned Gibson his first million dollar salary.[21]

Hollywood

Early Hollywood years

Mel Gibson's first American film was Mark Rydell’s 1984 drama The River, in which he and Sissy Spacek played struggling Tennessee farmers. Gibson then starred in the gothic romance Mrs. Soffel for Australian director Gillian Armstrong. He and Matthew Modine played condemned convict brothers opposite Diane Keaton as the warden's wife who visits them to read the Bible. In 1985, after working on four films in a row, Gibson took almost two years off at his Australian cattle ranch. He returned to play the role of Martin Riggs in Lethal Weapon, a film which helped to cement his status as a Hollywood star. Gibson's next film was Robert Towne’s Tequila Sunrise, followed by Lethal Weapon 2 in 1989. After starring in three films back-to-back, Bird on a Wire, Air America, and Hamlet, Gibson took another hiatus from Hollywood.

1990s

During the 1990s, Gibson used his boxoffice power to alternate between commercial and personal projects. His films in the first half of the decade were Forever Young, Lethal Weapon 3, Maverick, and Braveheart. He then starred in Ransom, Conspiracy Theory, Lethal Weapon 4, and Payback. Gibson also served as the speaking and singing voice of John Smith in Disney’s Pocahontas.

After 2000

In 2000, Gibson acted in three films that each grossed over $100 million: The Patriot, Chicken Run, and What Women Want. In 2002, Gibson appeared in the Vietnam War drama We Were Soldiers and M. Night Shyamalan’s Signs, which became the highest-grossing film of Gibson’s acting career.[22] While promoting Signs, Gibson said that he no longer wanted to be a movie star and would only act in film again if the script were truly extraordinary. In 2010, Gibson appeared in Edge of Darkness, which marked his first starring role since 2002[23] and was an adaptation of the BBC miniseries, Edge of Darkness.[24] In 2010 following an outburst at his ex girlfriend that was made public Gibson was dropped from the talent agency of Willam Morris[25]

Producer

After his success in Hollywood with the Lethal Weapon series, Gibson began to move into producing and directing. With partner Bruce Davey, Gibson formed Icon Productions in 1989 in order to make Hamlet. In addition to producing or co-producing many of Gibson's own star vehicles, Icon has turned out many other small films, ranging from Immortal Beloved to An Ideal Husband. Gibson has taken supporting roles in some of these films, such as The Million Dollar Hotel and The Singing Detective to improve their commercial prospects. Gibson has also produced a number of projects for television, including a biopic on The Three Stooges and the 2008 PBS documentary Carrier. Icon has grown beyond just a production company to an international distribution company and a film exhibitor in Australia and New Zealand.

Director

Mel Gibson has credited his directors, particularly George Miller, Peter Weir, and Richard Donner, with teaching him the craft of filmmaking and influencing him as a director. According to Robert Downey, Jr., studio executives encouraged Gibson in 1989 to try directing, an idea he rebuffed at the time.[26] Gibson made his directorial debut in 1993 with The Man Without a Face, followed two years later by Braveheart, which earned Gibson the Academy Award for Best Director. Gibson had long planned to direct a remake of Fahrenheit 451, but in 1999 the project was indefinitely postponed because of scheduling conflicts.[27] Gibson was scheduled to direct Robert Downey, Jr. in a Los Angeles stage production of Hamlet in January 2001, but Downey's drug relapse ended the project.[28] In 2002, while promoting We Were Soldiers and Signs to the press, Gibson mentioned that he was planning to pare back on acting and return to directing.[29] In September 2002, Gibson announced that he would direct a film called The Passion in Aramaic and Latin with no subtitles because he hoped to "transcend language barriers with filmic storytelling."[30] In 2004, he released the controversial film The Passion of the Christ, which he co-wrote, co-produced, and directed. Gibson directed a few episodes of Complete Savages for the ABC network. In 2006, he directed the action-adventure film Apocalypto, his second film to feature sparse dialogue in a non-English language.

Honors

On July 25, 1997, Gibson was named an honorary Officer of the Order of Australia (AO), in recognition of his "service to the Australian film industry". The award was honorary because substantive awards are made only to Australian citizens.[31][32] In 1985, Gibson was named "The Sexiest Man Alive" by People, the first person to be named so.[33] Gibson quietly declined the Chevalier des Arts et Lettres from the French government in 1995 as a protest against France's resumption of nuclear testing in the Southwest Pacific.[34] Time magazine chose Mel Gibson and Michael Moore as Men of the Year in 2004, but Gibson turned down the photo session and interview, and the cover went instead to George W. Bush.[35]

Landmark films

Mad Max series

Gibson got his breakthrough role as the leather-clad post-apocalyptic survivor in George Miller's Mad Max. The independently-financed blockbuster earned Gibson $15,000 and helped to make him an international star everywhere but in the United States, where the actors' Australian accents were dubbed with American accents. The original film spawned two sequels: Mad Max 2 (known in North America as The Road Warrior), and Mad Max 3 (known in North America as Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome). A fourth movie, Mad Max 4: Fury Road, is in development, but both Gibson and George Miller have indicated that the starring role would go to a younger actor.[36]

Gallipoli

Gibson played the role of the cynical Frank Dunne alongside co-star Mark Lee in the 1981 Peter Weir film. Gallipoli is about several young men from rural Western Australia who enlist in the Australian Army during the First World War. They are sent to Turkey, where they take part in the Gallipoli Campaign. During the course of the movie, the young men slowly lose their innocence about the purpose of war. The climax of the movie occurs on the ANZAC battlefield at Gallipoli and depicts the brutal attack at the Nek. According to Gibson, “Gallipoli was the birth of a nation. It was the shattering of a dream for Australia. They had banded together to fight the Hun and died by the thousands in a dirty little trench war."[37][verification needed] The critically-acclaimed film helped to further launch Gibson's career. He won the award for Best Actor in a Leading Role from the Australian Film Institute.

The Year of Living Dangerously

Gibson played a naïve but ambitious journalist opposite Sigourney Weaver and Linda Hunt in Peter Weir’s atmospheric 1982 film The Year of Living Dangerously, based on the novel of the same name by Christopher Koch. The movie was both a critical and commercial success, and the upcoming Australian actor was heavily marketed by MGM studio. In his review of the film, Vincent Canby of the New York Times wrote, "If this film doesn't make an international star of Mr. Gibson, then nothing will. He possesses both the necessary talent and the screen presence."[38]

Gibson was initially reluctant to accept the role of Guy Hamilton. "I didn't necessarily see my role as a great challenge. My character was, like the film suggests, a puppet. And I went with that. It wasn't some star thing, even though they advertised it that way."[39] Gibson saw some similarities between himself and the character of Guy. "He's not a silver-tongued devil. He's kind of immature and he has some rough edges and I guess you could say the same for me."[16] Gibson has cited this screen performance as his personal favorite.[when?]

The Bounty

Gibson followed the footsteps of Errol Flynn, Clark Gable, and Marlon Brando by starring as Fletcher Christian in a cinematic retelling of the mutiny on the Bounty. The resulting 1984 film The Bounty is considered to be the most historically accurate version. However, Gibson thinks that the film's revisionism did not go far enough. He stated that his character should have been portrayed as more of a villain and described Anthony Hopkins's performance as William Bligh as the best aspect of the film.[39]

Lethal Weapon series

Gibson moved into more mainstream commercial filmmaking with the popular buddy cop Lethal Weapon series, which began with the 1987 original. In the films he played LAPD Detective Martin Riggs, a recently widowed Vietnam veteran with a death wish and a penchant for violence and gunplay. In the films, he is partnered with a reserved family man named Roger Murtaugh (Danny Glover). Following the success of Lethal Weapon, director Richard Donner and principal cast revisited the characters in three sequels, Lethal Weapon 2 (1989), Lethal Weapon 3 (1993), and Lethal Weapon 4 (1998). This series would come to exemplify the subgenre of the buddy film.

Hamlet

Gibson made the unusual transition from the action to classical genres, playing the melancholic Danish prince in Franco Zeffirelli's Hamlet. Gibson was cast alongside such experienced Shakespearean actors as Ian Holm, Alan Bates, and Paul Scofield. He described working with his fellow cast members as similar to being "thrown into the ring with Mike Tyson".

The film met with critical and marketing success and remains steady in DVD sales. It also marked the transformation of Mel Gibson from action hero to serious actor and filmmaker.

Braveheart

Mel Gibson directed, produced, and starred in Braveheart, an epic telling of the legend of Sir William Wallace, a 13th century Scottish patriot. Gibson received two Academy Awards, Best Director and Best Picture for his second directorial effort. Braveheart influenced the Scottish nationalist movement and helped to revive the film genre of the historical epic. The Battle of Stirling Bridge sequence in Braveheart is considered by critics to be one of the all-time best directed battle scenes.[40]

The Passion of the Christ

Gibson directed, produced, co-wrote, and self-funded the 2004 film The Passion of the Christ, which chronicled the passion and death of Jesus Christ. The cast spoke the languages of Aramaic, Latin, and Hebrew. Although Gibson originally announced his intention to release the film without subtitles; he relented on this point for theatrical exhibition. The highly controversial film sparked divergent reviews, ranging from high praise to criticism of the violence and charges of anti-Semitism. Gibson also sparked controversy with his statements regarding New York Times writer Frank Rich, "I want to kill him. I want his intestines on a stick.... I want to kill his dog" in response to Rich's suggestion that the film could fuel anti-Semitism.[41][42]

The movie grossed US$611,899,420 worldwide and $370,782,930 in the US alone, surpassing any motion picture starring Gibson. In US box offices, it became the eighth highest-grossing film in history and the highest-grossing rated R film of all time. The film was nominated for three Academy Awards and won the People's Choice Award for Best Drama.

Apocalypto

Gibson further established his reputation as a director with his 2006 action-adventure film Apocalypto. Gibson's fourth directorial effort is set in Mesoamerica during the early 16th century against the turbulent end times of a Maya civilization. The sparse dialogue is spoken in the Yucatec Maya language by a cast of Native American descent.

Future films

In March 2007, Gibson told a screening audience that he was preparing another script with Farhad Safinia about the writing of the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).[43] Gibson's company has long owned the rights to The Professor and the Madman, which tells the story of the creation of the OED.[44]

Gibson has dismissed the rumors that he is considering directing a film about Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa.[45][46][47] Asked in September 2007 if he planned to return to acting and specifically to action roles, Gibson said:

- "I think I’m too old for that, but you never know. I just like telling stories. Entertainment is valid and I guess I’ll probably do it again before it's over. You know, do something that people won’t get mad with me for."[48]

In 2005, the film “Sam and George” was announced as the seventh collaboration between director Richard Donner and Gibson. In February 2009, Donner said that this Paramount project was “dead,”[49] but that he and Gibson were planning another film based on an original script by Brian Helgeland for production in fall 2009.[50]

It was reported in 2009 that Gibson would star in The Beaver, a film directed by former Maverick co-star, Jodie Foster.[51] He has also expressed an intention to direct a movie set during the Viking Age, starring Leonardo DiCaprio. The as-yet untitled film, like The Passion of the Christ and Apocalypto, will feature dialogue in period languages.[52]

In June 2010, Gibson was in Brownsville, Texas, filming scenes for another movie, tentatively titled How I Spent My Summer Vacation, about a career criminal put in a tough prison in Mexico.[53]

Personal life

Family

Gibson met Robyn Denise Moore in the late 1970s soon after filming Mad Max when they were both tenants at a house in Adelaide. At the time, Robyn was a dental nurse and Mel was an unknown actor working for the South Australian Theatre Company.[54] On June 7, 1980, they were married in a Catholic church in Forestville, New South Wales.[55] The couple have one daughter, six sons, and two grandchildren.[56] Their seven children are Hannah (born 1980), twins Edward and Christian (born 1982), William (born 1985), Louis (born 1988), Milo (born 1990), and Thomas (born 1999).

Daughter Hannah Gibson married blues musician Kenny Wayne Shepherd on September 16, 2006.[57][58]

After nearly three years of separation, Robyn Gibson filed for divorce on April 13, 2009, citing irreconcilable differences. In a joint statement, the Gibsons declared, "Throughout our marriage and separation we have always strived to maintain the privacy and integrity of our family and will continue to do so."[8]

Gibson's former girlfriend, Russian pianist Oksana Grigorieva, gave birth to their daughter Lucia on October 30, 2009.[59][60] In April 2010, it was made public that they had split.[61] The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department has launched a domestic violence investigation against Gibson.[62][63] Gibson has filed for a restraining order against Grigorieva to prevent her speaking publicly about the case.[64][65]

Investments

Gibson is a property investor, with multiple properties in Malibu, California, several locations in Costa Rica, a private island in Fiji and properties in Australia.[66][67] In December 2004, Gibson sold his 300-acre (1.2 km2) Australian farm in the Kiewa Valley for $6 million.[68] Also in December 2004, Gibson purchased Mago Island in Fiji from Tokyu Corporation of Japan for $15 million. Descendants of the original native inhabitants of Mago, who were displaced in the 1860s, have protested the purchase. Gibson stated it was his intention to retain the pristine environment of the undeveloped island.[69] In early 2005, he sold his 45,000-acre (180 km2) Montana ranch to a neighbor.[70] In April 2007 he purchased a 400-acre (1.6 km2) ranch in Costa Rica for $26 million, and in July 2007 he sold his 76-acre (310,000 m2) Tudor estate in Connecticut (which he purchased in 1994 for $9 million) for $40 million to an unnamed buyer.[71] Also that month, he sold a Malibu property for $30 million that he had purchased for $24 million two years before.[72] In 2008, he purchased the Malibu home of David Duchovny and Téa Leoni.[73]

Religious and political views

Faith

Gibson was raised a Traditionalist Catholic. When asked about the Catholic doctrine of "Extra Ecclesiam nulla salus", Gibson replied, "There is no salvation for those outside the Church … I believe it. Put it this way. My wife is a saint. She's a much better person than I am. Honestly. She's, like, Episcopalian, Church of England. She prays, she believes in God, she knows Jesus, she believes in that stuff. And it's just not fair if she doesn't make it, she's better than I am. But that is a pronouncement from the chair. I go with it."[74][41] When he was asked whether John 14:6 is an intolerant position, he said that "through the merits of Jesus' sacrifice… even people who don't know Jesus are able to be saved, but through him."[75] Acquaintance Father William Fulco has said that Gibson denies neither the Pope nor Vatican II.[76] Gibson told Diane Sawyer that he believes non-Catholics and non-Christians can go to heaven.[77][78]

Gibson's traditionalist Catholic beliefs have been the target of criticism, especially during the controversy over his film The Passion of the Christ. Gibson stated in the Diane Sawyer interview that he feels that his "human rights were violated" by the often vitriolic attacks on his person, his family, and his religious beliefs which were sparked by The Passion.[77]

Politics

Gibson has been called everything from “ultraconservative”[79] to “politically very liberal” (by acquaintance William Fulco).[76] He has denied that he is a Republican.[80]

Gibson complimented filmmaker Michael Moore and his documentary Fahrenheit 9/11 when he and Moore were recognized at the 2005 People's Choice Awards.[81] Gibson's Icon Productions originally agreed to finance Moore's film, but later sold the rights to Miramax Films. Moore said that his agent Ari Emanuel claimed that "top Republicans" called Mel Gibson to tell him, "don’t expect to get more invitations to the White House".[82] Icon's spokesman dismissed this story, saying "We never run from a controversy. You'd have to be out of your mind to think that of the company that just put out The Passion of the Christ."[83]

In a July 1995 interview with Playboy magazine, Gibson said President Bill Clinton was a "low-level opportunist" and someone was "telling him what to do". He said that the Rhodes Scholarship was established for young men and women who want to strive for a "new world order" and this was a campaign for Marxism.[84] Gibson later backed away from such conspiracy theories saying, "It was like: 'Hey, tell us a conspiracy'... so I laid out this thing, and suddenly, it was like I was talking the gospel truth, espousing all this political shit like I believed in it."[85] In the same 1995 Playboy interview, Gibson argued that men and women are unequal as a reason against women priests.[84][86][87]

In 2004, he publicly spoke out against taxpayer-funded embryonic stem-cell research that involves the cloning and destruction of human embryos.[88] In March 2005, he condemned the outcome of the Terri Schiavo case, referring to Schiavo's death as "state-sanctioned murder".[89]

Gibson questioned the Iraq War in March 2004.[90] In 2006, Gibson said that the "fearmongering" depicted in his film Apocalypto "reminds me a little of President Bush and his guys."[79]

Allegations of homophobia

The Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) accused Gibson of homophobia after a December 1991 interview in the Spanish newspaper El País.[87][91] Gibson later defended his comments[91] and rejected calls to apologise.[84] However, Gibson joined GLAAD in hosting 10 lesbian and gay filmmakers for an on-location seminar on the set of the movie Conspiracy Theory in January 1997.[92] In 1999 when asked about the comments to El País, Gibson said, "I shouldn't have said it, but I was tickling a bit of vodka during that interview, and the quote came back to bite me on the ass."[85]

Gibson has been accused of homophobia in his films Braveheart[93] and The Passion of the Christ.[94]

Allegations of anti-semitism

Gibson's 2004 film The Passion of the Christ sparked a fierce debate over alleged anti-semitic imagery and overtones. Gibson denied that the film was anti-semitic, but critics remained divided. Some agreed that the film was consistent with the Gospels and traditional Catholic teachings, while others argued that it reflected a selective reading of the Gospels.[95]

A leaked report revealed that during Gibson's July 28, 2006 arrest for driving under the influence he made anti-semitic remarks to arresting officer James Mee, who is Jewish, saying "Fucking Jews...the Jews are responsible for all the wars in the world."[96][97] Gibson issued two apologies for the incident through his publicist,[98][99] and in a later interview with Diane Sawyer, he affirmed the accuracy of the quotations.[100]

Allegations of sexism and domestic violence

In July 2010, it was reported that he had been caught on voicemail making misogynist remarks, telling his ex-girlfriend Oksana Grigorieva, "if you get raped by a pack of niggers, it will be your fault".[101] He was also recorded threatening to burn down Grigorieva's house[101] and that Grigorieva would perform fellatio on Gibson.[102] Gibson was barred from coming near Grigorieva or her daughter due to a domestic violence restraining order.[101] Gloria Allred stated, "As an attorney who has represented many sexual assault victims and as a woman who is a survivor of rape myself, I want you to know how deeply offensive, appalling and harmful your reported statements are."[103]

In another alleged recorded conversation, Gibson acknowledged punching Grigorieva in the face, claiming she "deserved" it.[104] The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department has launched a domestic violence investigation against Gibson.[104][63] Reports also emerged that Gibson had been caught on tape threatening Grigorieva with the statement, "I'll put you in the rose garden because you know I'm capable of it."[105][106]

Gibson's recorded statements have drawn concern from womens' groups. Erin Matson of the National Organization for Women expressed hope that the release of the Gibson tapes would ignite debate about domestic violence, saying "what we're looking at is not a personal or private issue but a public health issue."[106] Rita Smith, of the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, stated that Gibson exhibited behavior of a "typical batterer" with "typical control tactics".[105][107]

Allegations of racism

The July 2010 reports of voicemail recordings also included alleged racist remarks, with Gibson using the word "niggers".[101] Civil rights activists commented that Gibson had shown "patterns of racism, sexism and anti-Semitism" and called for a boycott of Gibson's movies.[108][103][103]

On July 8, 2010, Gibson was alleged to have made a racial slur against Latinos using the term "wetbacks" as he suggested turning in one of his employees to immigration authorities.[109] On July 9, 2010, some of the Gibson audio recordings were posted on the internet.[110] The same day Gibson was dropped by his agency, William Morris Endeavor.[110]

Alcohol abuse

Gibson has said that he started drinking at the age of thirteen.[111] In a 2002 interview about his time at NIDA, Gibson said, "I had really good highs but some very low lows. I found out recently I'm manic depressive."[112]

Gibson was banned from driving in Ontario for three months in 1984 after rear-ending a car in Toronto while under the influence of alcohol.[113] He retreated to his Australian farm for over a year to recover, but he continued to struggle with drinking. Despite this problem, Gibson gained a reputation in Hollywood for professionalism and punctuality, so that Lethal Weapon 2 director Richard Donner was shocked when Gibson confided that he was drinking five pints of beer for breakfast.[77] Reflecting in 2003 and 2004, Gibson said that despair in his mid-30s led him to contemplate suicide, and he meditated on Christ's Passion to heal his wounds.[74][77][114] He took more time off acting in 1991 and sought professional help. That year, Gibson's attorneys were unsuccessful at blocking the Sunday Mirror from publishing what Gibson shared at AA meetings.[115][clarification needed] In 1992, Gibson provided financial support to Hollywood's Recovery Center, saying, "Alcoholism is something that runs in my family. It's something that's close to me. People do come back from it, and it's a miracle."[116]

On July 28, 2006, Gibson was arrested for DUI while speeding in his vehicle with an open container of alcohol. He admitted to making anti-semitic remarks during his arrest and apologized for his "despicable" behavior, saying the comments were "blurted out in a moment of insanity"[117] and asked to meet with Jewish leaders to help him "discern the appropriate path for healing."[118] After Gibson's arrest, his publicist said he had entered a recovery program to battle alcoholism. On August 17, 2006, Gibson pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor drunken-driving charge and was sentenced to three years on probation.[117] He was ordered to attend self-help meetings five times a week for four and a half months and three times a week for the remainder of the first year of his probation. He was also ordered to attend a First Offenders Program, was fined $1,300, and his license was restricted for 90 days.[117]

In a October 12, 2006 interview with Diane Sawyer, Gibson spoke about his struggle to remain sober:

The risk of everything — life, limb, family — is not enough to keep you from it… You cannot do it of yourself. And people can help, yeah. But it's God. You've got to go there. You've got to do it. Or you won't survive….[119]

At a May 2007 progress hearing, Gibson was praised for his compliance with the terms of his probation, his extensive participation in a self-help program, beyond what was required.[120]

Prankster

Mel Gibson has a reputation for practical jokes, puns, Stooge-inspired physical comedy, and doing outrageous things to shock people. As a director he sometimes breaks the tension on set by having his actors perform serious scenes wearing a red clown nose.[121] Helena Bonham Carter, who appeared alongside him in Hamlet, said of him, "He has a very basic sense of humor. It's a bit lavatorial and not very sophisticated."[122] In addition to inserting several homages to the Three Stooges in his Lethal Weapon movies, Gibson produced a 2000 television movie about the comedy group which starred Michael Chiklis as Curly Howard. As a gag, Gibson inserted a single subliminal frame of himself smoking a cigarette into the 2005 teaser trailer of Apocalypto.[123]

Philanthropy

Gibson and his former wife are believed to have contributed a substantial amount of money to various charities, one of which is Healing the Children. According to Cris Embleton, one of the founders, the Gibsons gave millions to provide lifesaving medical treatment to needy children worldwide.[124][125] They also supported the restoration of Renaissance artwork[126] and giving millions of dollars to NIDA.[127]

Gibson donated $500,000 to the El Mirador Basin Project to protect the last tract of virgin rain forest in Central America and to fund archeological excavations in the "cradle of Mayan civilization."[128] In July 2007, Gibson again visited Central America to make arrangements for donations to the indigenous population. Gibson met with Costa Rican President Oscar Arias to discuss how to "channel the funds."[129] During the same month, Gibson pledged to give financial assistance to a Malaysian company named Green Rubber Global for a tire recycling factory located in Gallup, New Mexico.[130] While on a business trip to Singapore in September 2007, Gibson donated to a local charity for children with chronic and terminal illnesses.[131]

Filmography and awards

Actor

Template:Filmography table begin

|-

! Year

! Film

! Role

! Notes

|-

! rowspan="2" | 1977

| Summer City

| Scallop

|

|-

| I Never Promised You a Rose Garden

| Baseball Player

| Uncredited

|-

! rowspan="2" | 1979

| Mad Max

| Mad Max Rockatansky

|

|-

| Tim

| Tim

| Australian Film Institute Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role

|-

! 1980

| The Chain Reaction

| Bearded mechanic

| Uncredited

|-

! rowspan="2" | 1981

| Mad Max 2

| Max Rockatansky

| aka The Road Warrior

Nominated—Saturn Award for Best Actor

|-

| Gallipoli

| Frank Dunne

| Australian Film Institute Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role

|-

! rowspan="2" | 1982

| The Year of Living Dangerously

| Guy Hamilton

| Nominated—Australian Film Institute Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role

|-

| Attack Force Z

| Captain P.G. (Paul) Kelly

|

|-

! rowspan="3" | 1984

| Mrs. Soffel

| Ed Biddle

|

|-

| The River

| Tom Garvey

|

|-

| The Bounty

| Fletcher Christian

|

|-

! 1985

| Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome

| Mad Max

| Max Rockatansky

|-

! 1987

| Lethal Weapon

| Sergeant Martin Riggs

|

|-

! 1988

| Tequila Sunrise

| Dale "Mac" McKussic

|

|-

! 1989

| Lethal Weapon 2

| Sergeant Martin Riggs

|

|-

! rowspan="3" | 1990

| Hamlet

| Prince Hamlet

|

|-

| Air America

| Gene Ryack

|

|-

| Bird on a Wire

| Rick Jarmin

|

|-

! rowspan="2" | 1992

| Forever Young

| Capt. Daniel McCormick

|

|-

| Lethal Weapon 3

| Sergeant Martin Riggs

| MTV Movie Award for Best Action Sequence

MTV Movie Award for Best On-Screen Duo with Danny Glover

Nominated—MTV Movie Award for Best Kiss with Rene Russo

Nominated—MTV Movie Award for Most Desirable Male

|-

! rowspan="2" | 1993

| The Man Without a Face

| Justin McLeod

|

|-

| The Chili Con Carne Club

| Mel

|

|-

! 1994

| Maverick

| Bret Maverick

|

|-

! rowspan="2" | 1995

| Pocahontas

| John Smith

| Voice

|-

| Braveheart

| William Wallace

| Nominated—MTV Movie Award for Best Performance - Male

Nominated—MTV Movie Award for Most Desirable Male

|-

! 1996

| Ransom

| Tom Mullen

| Blockbuster Entertainment Awards: Favorite Actor – Suspense

Nominated—Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama

|-

! rowspan="3" | 1997

| FairyTale: A True Story

| Frances' Father

| Uncredited

|-

| Conspiracy Theory

| Jerry Fletcher

| Blockbuster Entertainment Awards — Favorite Actor – Suspense

|-

| Fathers' Day

| Scott the Body Piercer

| Uncredited

|-

! 1998

| Lethal Weapon 4

| Sergeant Martin Riggs

| Nominated—MTV Movie Award for Best Action Sequence with Danny Glover

|-

! 1999

| Payback

| Porter

|

|-

! rowspan="4" | 2000

| What Women Want

| Nick Marshall

| Nominated—Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy

|-

| The Patriot

| Benjamin Martin

| Blockbuster Entertainment Awards: Favorite Actor — Drama

People's Choice Awards — Favorite Motion Picture Star in a Drama

Nominated—MTV Movie Award for Best Performance - Male

|-

| Chicken Run

| Rocky

| Voice

|-

| The Million Dollar Hotel

| Detective Skinner

|

|-

! rowspan="2" | 2002

| We Were Soldiers

| Lt. Col. Hal Moore

|

|-

| Signs

| Rev. Graham Hess

|

|-

! 2003

| The Singing Detective

| Dr. Gibbon

|

|-

! 2004

| Paparazzi

| Anger Management Therapy Patient

| Uncredited

|-

! 2006

| Who Killed the Electric Car?

| Himself

|

|-

! 2010

| Edge of Darkness

| Thomas Craven

|

|-

! 2010

| The Beaver

| Walter Black

| post-production

Template:Filmography table end

Director

Template:Filmography table begin

|-

! 1993

| The Man Without a Face

|

|-

! 1995

| Braveheart

| Academy Award for Best Director

Golden Globe Award for Best Director

Broadcast Film Critics Association Award for Best Director

National Board of Review Special Achievement in Filmmaking

ShoWest Award: Director of the Year

Nominated—BAFTA Award for Best Direction

Nominated—Directors Guild of America Award

|-

! 2004

| The Passion of the Christ

| Satellite Award for Best Director

|-

! 2006

| Apocalypto

|

Template:Filmography table end

Producer

Template:Filmography table begin

|-

! 1992

| Forever Young

| Executive producer – uncredited

|-

! 1995

| Braveheart

| Academy Award for Best Picture

Nominated—BAFTA Award for Best Film not in the English Language

|-

! 2000

| The Three Stooges

| Television

Executive producer

|-

! 2001

| Invincible

| Television

Executive producer

|-

! rowspan="2" | 2003

| Family Curse

| Television

Executive producer

|-

| The Singing Detective

|

|-

! rowspan="2" | 2004

| The Passion of the Christ

| People's Choice Awards — Favorite Motion Picture Drama

|-

| Paparazzi

|

|-

! 2005

| Leonard Cohen: I'm Your Man

| Television

Executive producer

|-

! 2006

| Apocalypto

| Nominated—Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film

Nominated—BAFTA Award for Best Film not in the English Language

Nominated—Broadcast Film Critics Association Award for Best Foreign Language Film

|-

! 2008

| Another Day in Paradise

| Television

Template:Filmography table end

Screenwriter

Template:Filmography table begin |- ! 2004 | The Passion of the Christ | Screenplay |- ! 2006 | Apocalypto | Template:Filmography table end

Other awards and accomplishments

- People's Choice Awards: Favorite Motion Picture Actor (1990, 1996, 2000, 2002, 2003)

- ShoWest Award: Male Star of the Year (1993)

- American Cinematheque Gala Tribute: American Cinematheque Award (1995)

- Hasty Pudding Theatricals: Man of the Year (1997)

- Australian Film Institute: Global Achievement Award (2002)

- Honorary Doctorate Recipient and Undergraduate Commencement Speaker, Loyola Marymount University (2003)

- World's most powerful celebrity by US business magazine Forbes (2004)

- Hollywood Reporter Innovator of the Year (2004)

- Honorary fellowship in Performing Arts by Limkokwing University (2007)

- Outstanding Contribution to World Cinema Award at the Irish Film and Television Awards (2008)[132]

References

- ^ "1995 Academy Awards". Filmsite.org. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ Jesus helps Mel hit No. 1: Controversial film gives Gibson the most weight on Forbes power list; Britney off the chart again June 18, 2004

- ^ Box Office Mojo.com Domestic Total Gross:$370,782,930 60.6% + Foreign: $241,116,490 39.4%

- ^ http://boxofficemojo.com/people/chart/?view=Actor&id=melgibson.htm

- ^ "Mel Gibson to be honoured at IFTA ceremony – RTÉ Ten". Rte.ie. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ Lawrence Donegan. "Observer profile". Guardian. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ "Ancestry of Mel Gibson". Wargs.com. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ a b "Mel Gibson's Wife Files for Divorce". TMZ.com. 2009-04-13. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- ^ Michael Dwyer, The Irish Times film critic, interviewed on RTÉ Radio 1's This week programme, August 6, 2006.

- ^ Stephen M. Silverman. "Jonathan Rhys Meyers Crowned Best Actor in Ireland". People Magazine. Retrieved 2008-03-02.

- ^ Mel Gibson: Living Dangerously, Wensley Clarkson, Thunder's Mouth Press, New York, 1993, page 30.

- ^ Wendy Grossman. "Is the Pope Catholic?". Dallas Observer. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ^ "Mel Gibson's Biography/Filmography - Celebrity Gossip | Entertainment News | Arts And Entertainment". FOXNews.com. 2006-08-08. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ^ "A son's dangerous passion, in the name of the father - OpinionGerardHenderson". www.smh.com.au. 2004-03-02. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ^ Vincent Canby (1982-08-29). "New Faces Brighten a Mixed Batch of Movies". New York Times.

- ^ a b Vernon Scott (1983-02-24). "Mel Gibson: Australia's new hunk". U.P.I.

- ^ Clarkson, Wensley. Mel Gibson: Living Dangerously. pages 170–171.

- ^ Graeme Blundell (2008-05-24). "Youth with stars in their eyes". The Australian.

- ^ "A Night on Mount Edna," December 15, 1990

- ^ Robert Weller (1993-07-17). "Welcome to Telluride – Now Go Away". Associated Press.

- ^ Valdez, Joe (2007-12-20). "Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985)". This Distracted Globe.

- ^ "Mel Gibson". Box Office Mojo accessdate=2009-05-24.

{{cite web}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help); line feed character in|work=at position 16 (help) - ^ Fleming, Michael (2008-04-28). "Mel Gibson returns for 'Darkness'". Variety. Retrieved 2009-03-29.

- ^ By. "Mel Gibson returns for 'Darkness' – Entertainment News, Gotham, Media – Variety". Variety.com. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ "Mel Gibson's agency drops actor after racist and sexist rant, alleged attack against ex-girlfriend". Retrieved 2010-07-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|Publisher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ Erin McWhirter (2008-05-01). "Robert Downey Jr. has irons in the fire". The Courier Mail.

- ^ Dan Cox and Michael Fleming (1999-02-01). "Gibson in talks for 'Patriot'". Daily Variety.

- ^ "Gibson Downey Jr becomes Hamlet". BBC. 2000-09-21.

- ^ Tiffany Rose (2002-09-08). "Mel Gibson: 'I think I'm mellowing in my old age'". London: The Independent.

- ^ "Jesus Christ!! What – Ain't It Cool News: The best in movie, TV, DVD, and comic book news". Aintitcool.com. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ "It's an Honour - Honours - Search Australian Honours". Itsanhonour.gov.au. 1997-07-25. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ^ Daniel Vidoni. "Order of Australia Association". Theorderofaustralia.asn.au. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ "Think You Know Sexy?". People.com. 2005-11-03. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ Galloway, Stephen. The Hollywood Reporter. October 30, 1995. "It was a definite decision to make a protest against the nuclear tests", said Gibson, who is mad at French President Jacques Chirac for deciding to detonate some bombs in the Pacific.

- ^ Michael Moore Defends Cruise, Slags Gibson September 16, 2006

- ^ N'Gai Croal (2008-03-12). "Exclusive Exclusive: Writer-Director George Miller Announces 'Mad Max' As First Game From Creative Alliance With God of War II Director Cory Barlog".

- ^ Davin Seay (February 1983). "An American from Kangaroo-land hops to the top". Ampersand.

- ^ Vincent Canby (1983-01-21). "Year of Living Dangerously". New York Times.

- ^ a b Michael Fleming (July 2000). "Mel's Movies". Movieline.

- ^ The best – and worst – movie battle scenes April 2, 2007

- ^ a b Adato, Allison (2006-08-14). "Mel Gibson: 'I Am Deeply Ashamed'". People.com.

- ^ "Gibson's way with words". USA Today. 2006-08-01.

- ^ Event Report: "Mel Gibson Goes Mad At CSU" – CinemaBlend.com – March 23, 2007

- ^ Gussow, Mel (1998-09-07). "The Strange Case of the Madman With a Quotation for Every Word". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ 10 minutes with Mel Gibson: "When going green comes naturally" – The New Straits Times – September 1, 2007 – accessed September 9, 2007

- ^ "Mel Gibson to film in Panama?" – Opodo Travel News – March 7, 2007

- ^ Mel Gibson Thinking About Setting Next Splatter Film In Panama March 6, 2007

- ^ Enter the eco warrior The Star (Malaysia) – September 10, 2007 – accessed September 10, 2007

- ^ Adam Jahnke (February 27, 2009). "Inside Man: Richard Donner on Inside Moves".

- ^ Mr. Beaks (February 19, 2009). "Richard Donner And Mr. Beaks Talk INSIDE MOVES!". Aint It Cool News.

- ^ "Mel Gibson to star in 'Beaver'". Variety. 2009-07-09. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ^ "Mel Gibson to direct DiCaprio in Viking movie: report". France 24. 14 December 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ Hollywood Hits Home: Mel Gibson, film crew shoot scenes in Brownsville The Brownsville Herald

- ^ DEVLIN, REBEKAH (2007-10-16). "Star's family farewell father". The Advertiser. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ^ Mel Gibson: Living Dangerously, Wensley Clarkson, Thunder's Mouth Press, New York, 1993, page 125.

- ^ Bokun, Jane (2009-04-26). "Kenny Wayne Shepherd highlights festival". Schreveport Times. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ^ "Hannah Gibson marrying Shepherd". CBS News. 2006-09-18.

- ^ "Mel Gibson's Daughter Marries Guitarist". People. 2006-09-18.

- ^ Gina DiNunno. "Mel Gibson's Girlfriend Gives Birth to Baby Girl". TVGuide.com.

- ^ Leonard, Elizabeth (2009-05-25). "Rep: Mel Gibson and Girlfriend Are Expecting!". People. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ^ Elizabeth Leonard. "Mel Gibson and Oksana Grigorieva Split". People.com.

- ^ Barnett, Sophie (July 7, 2010). "Mel Faces Abuse Claims". MTV. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b "Mel Gibson investigated for domestic violence". Vancouver Sun. July 8, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010. Cite error: The named reference "abuseinvestigation2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Mel Gibson Files Restraining Order Against Baby Mama Oksana Grigorieva". Fox News. June 25, 2010. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- ^ "Gibson accused of racist, sexist rant". ABC News (Australia). July 2, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ Mel Gibson denied bid to reclassify estate as farm Jan 17, 2005

- ^ Mel Gibson: Hollywood Takes Sides August 4, 2006

- ^ Mel Gibson selling up September 16, 2004

- ^ "Displaced Fijians may sue island-buying Mel Gibson". Sydney Morning Herald. 2005-05-03. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- ^ "Gibson's neighbor buys his Beartooth Ranch". Deseret News. 2005-02-28. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- ^ Mel Gibson reportedly listing his Greenwich, CT estate for $39.5M; status of his Malibu properties is uncertain July 12, 2007

- ^ Mel Gibson sells Malibu home for $30 million: Star bought the property two years ago for $24 million July 30, 2007

- ^ Brenoff, Ann (2008-09-20). "Mel Gibson buys Malibu home of David Duchovny and Téa Leoni". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

- ^ a b Boyer, Peter J. The New Yorker. September 15, 2003

- ^ "Inside Mel Gibson's "Passion"." Salon. January 27, 2004.

- ^ a b “Whose Passion? Media, Faith & Controversy” panel discussion video, time 1:05

- ^ a b c d "Transcript of February 2004 Primetime". Archived from the original on 2005-07-16. Retrieved 2006-07-31.

- ^ Martin, Allie and Jenni Parker (2004-02-20). "Gibson's Words Fuel Controversy Already Sparked By 'Passion'". Agape Press.

- ^ a b Padgett/Veracruz, Tim. "Apocalypto Now." Time. March 19, 2006.

- ^ Weiner, Allison Hope. "The Year of Living Dangerously." Entertainment Weekly. December 8, 2006.

- ^ "Moore, Gibson: I Love His Work." Fox News. January 10, 2005.

- ^ Keough, Peter. "Not so hot: Fahrenheit 9/11 is more smoke than fire." Boston Phoenix. June 25, 2004.

- ^ Stein, Ruthe. "'Fahrenheit 9/11' too hot for Disney." San Francisco Chronicle. May 6, 2004.

- ^ a b c Grobel, Lawrence. "Interview: Mel Gibson". Playboy. July 1995. Vol. 42, No. 7, Pg. 51. Retrieved May 17, 2006.

- ^ a b Nui Te Koka. "Did I say that?" The Daily Telegraph. January 30, 1999, pg 33.

- ^ Grobel, Lawrence. Grobel, Lawrence. The art of the interview: lessons from a master of the craft. Three Rivers Press, 2004. ISBN 1400050715. p. 151.

- ^ a b DeAngelis, Michael. Gay Fandom and Crossover Stardom. Duke University Press, 2001. ISBN 0822327384p. 166.

- ^ "Braveheart Stands Athwart a Brave New World." National Review. November 1, 2004.

- ^ Rich, Frank (10 April 2005). "A Culture of Death, Not Life". New York Times. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ^ "Mel Gibson joins stars to question Iraq war." Sydney Morning Herald. March 18, 2004.

- ^ a b Wockner, Rex. "Mel Gibson, Circa 1992, "Refuses to Apologize to Gays"." San Francisco Bay Times. August 17, 2006. Quote: Asked what he thought of gay people, he said, "They take it up the ass." Gibson then proceeded to point at his posterior and said: "This is only for taking a shit." When reminded that he had worked closely with gay people at drama school, Gibson said, "They were good people, kind, I like them. But their thing is not my thing." When the interviewer asked if Gibson was afraid that people would think he is gay because he's an actor, Gibson replied, "Do I sound like a homosexual? Do I talk like them? Do I move like them? What happens is when you're an actor, they stick that label on you."

- ^ "Mel Gibson to Meet Up-and-Coming Lesbian and Gay Filmmakers." glaad.org.

- ^ Rotello, Gabriel. "Gays Should Beware of Men in Kilts." New York Newsday. June 1, 1995.

- ^ Clinton, Paul. "Review: A powerful, personal 'Passion'." CNN. February 25, 2004.

- ^ Some criticism of The Passion

- ^ New York Times July 30, 2006

- ^ Gibson's Anti-Semitic Tirade – Alleged Cover Up; TMZ.com; July 28, 2006

- ^ "Gibson's statement about anti-Semitic remarks". MSNBC. 2006-01-08. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ "Mel Gibson's Statement on His DUI Arrest". Sfgate.com. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ Stephen M. Silverman (2006-10-12). "Mel Gibson Admits He Drank After Arrest". Retrieved 2009-06-04.

- ^ a b c d Pilkington, Ed (July 2, 2010). "Mel Gibson faces flak again after alleged racist rant". The Guardian. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ Huffington Post, July 1, 2010

- ^ a b c Kaufman, Gil (July 2, 2010). "Mel Gibson Condemned For Alleged Racist, Sexist Rant Against Ex". MTV. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ a b McCartney, Anthony (July 12, 2010). "Gibson tape mentions alleged hitting of girlfriend". Associated Press. Washington Post. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- ^ a b "Mel Gibson allegedly admits punching Oksana Grigorieva in new tape". The Daily Telegraph (Australia). July 13, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ a b Thompson, Arienne (July 13, 2010). "For Mel Gibson, scandal puts him in a harsh light again". USA Today. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ McCartney, Anthony (July 9, 2010). "Website posts recording of racist Gibson rant". The Associated Press. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ Winton, Richard (July 2, 2010). "Civil rights activists condemn remarks allegedly made by Mel Gibson". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ "Mel Gibson Investigated for Domestic Violence! Plus: He's Caught in Another Racist Rant". Star (magazine). July 8, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b "Website Posts Recording of Gibson's Racist Rant, Actor Dropped by Talent Agency". Los Angeles Times. July 9, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Rant aftermath a gift, says Gibson." Herald Sun. January 15, 2007.

- ^ Murray, Elicia and Garry Maddox (2008-05-15). "Mel opens up, but ever so fleetingly". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ Seitz, Matt Zoller (1995-05-25). "Mel Gibson talks about Braveheart, movie stardom, and media treachery". Dallas Observer. Retrieved 2006-07-29.

- ^ Ryan, Tim (2004-02-22). "Mel Gibson's Passion". Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

- ^ The Advertiser. September 22, 1991

- ^ Higgins, Bill. Los Angeles Times. December 14, 1992.

- ^ a b c "Gibson takes first starring role in six years". Guardian.uk.co. London. 2008-04-29. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ "Gibson Asks Jews For Help To Find "Appropriate Path To Healing"". 2006-07-030.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Gibson: 'Public Humiliation on a Global Scale' Made Him Address Alcoholism". ABC News. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ^ "Mel Gibson Praised for Progress in Alcohol Rehab." Newsmax. May 12, 2007.

- ^ The Passion of Mel Gibson Jan. 19, 2003, Time.com Accessed September 9, 2007

- ^ Wensley Clarkson's "Mel Gibson: Living Dangerously", page 287

- ^ Apple Inc. (2006-12-08). "Teaser Trailer. Frame 2546. Timecode 01:01:47:03. Time 00:01:46". Apple.com. Retrieved 2010-07-12.

- ^ "Actor and Director Mel Gibson Donates $10 Million." UCLA.edu Newsroom.

- ^ "Mel's $14m donation." Sydney Morning Herald. October 13, 2004.

- ^ "Mel Gibson and Sting to fund David restoration". London: The Daily Telegraph. 2003-07-16. Retrieved 2007-09-23.

- ^ "Meln An Interview with John Clark". Quadrant Magazine. May 2004. Retrieved 2007-09-23.

- ^ "Enter the eco warrior". The Star (Malaysia). 2007-09-10. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

- ^ "Mel Gibson Meets With Costa Rican Leader." ABC News. July 10, 2007.

- ^ "Mel Gibson Backs Green Rubber." EcoRazzi.com. July 12, 2007.

- ^ "Mel Gibson makes S$25,000 donation to charity organisation". Channel NewsAsia. 2007-09-14. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- ^ "RTÉ.ie Entertainment: Mel Gibson to be honoured at IFTA ceremony". Rte.ie. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

Bibliography

- McCarty, John (2001). The Films of Mel Gibson. New York: Citadel. ISBN 0806522267.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Clarkson, Wensley (2004). Mel Gibson: Man on a Mission. London: John Blake. ISBN 1-85782-537-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- Please use a more specific IMDb template. See the documentation for available templates.

- Mel Gibson at Curlie

- "Exclusive: Mel Gibson's Apocalyto Now" (sic), by Tim Padgett/Veracruz, Time magazine

- 1956 births

- Living people

- 20th-century actors

- 21st-century actors

- 21st-century writers

- Actors from New York

- American film actors

- American film directors

- American people of Australian descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American philanthropists

- American Roman Catholics

- American screenwriters

- American stage actors

- American television actors

- American television producers

- American Traditionalist Catholics

- American voice actors

- Antisemitism

- Best Director Academy Award winners

- Best Director Golden Globe winners

- Former students of the National Institute of Dramatic Art

- MTV Movie Award winners

- Officers of the Order of Australia

- People convicted of alcohol-related driving offenses

- People from Westchester County, New York

- People self-identifying as alcoholics

- People with bipolar disorder

- Producers who won the Best Picture Academy Award

- Racism in the United States