Transcendental Meditation: Difference between revisions

ce syntax... |

added another Cochrane review, and removed attempts to refute good evidence with bad evidence |

||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

===Mental function=== |

===Mental function=== |

||

A 2010 review by the [[Cochrane collaboration]] was unable to draw any conclusions regarding the effectiveness of meditation therapy ( including TM ) for ADHD due to the lack of suitable evidence.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Krisanaprakornkit T, Ngamjarus C, Witoonchart C, Piyavhatkul N |title=Meditation therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) |journal=Cochrane Database Syst Rev |volume=6 |issue= |pages=CD006507 |year=2010 |pmid=20556767 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD006507.pub2 |url=}}</ref> A 2006 review by the Cochrane collabortion found that there was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding the effectiveness of meditation for anxiety disorders. The review found that, as of 2006, two randomized controlled trials had been done on this topic, one of which was on TM, and concluded that meditation is equivalent to relaxation therapy.<ref name=Cochrane06>{{cite journal |author=Krisanaprakornkit T, Krisanaprakornkit W, Piyavhatkul N, Laopaiboon M |title=Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders |journal=Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |volume= |issue=1 |pages=CD004998 |year=2006 |pmid=16437509 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD004998.pub2 |ref=harv}}</ref> |

|||

A 2003 review by Peter Canter and [[Edzard Ernst]] concluded that evidence does not support a specific or cumulative effect from TM on [[cognitive function]]. The review did find positive results in studies that recruited people with favorable opinions of TM, and used passive control procedures.<ref name="Wien Klin Wochenschr.">{{cite journal |author=Canter PH, Ernst E |title=The cumulative effects of Transcendental Meditation on cognitive function--a systematic review of randomised controlled trials |journal=Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. |volume=115 |issue=21-22 |pages=758–66 |year=2003 |month=November |pmid=14743579 |doi= 10.1007/BF03040500|url= |ref=harv}}</ref> Edzard Ernst, professor of complementary medicine at the Peninsula Medical School in Exeter, was quoted in ''The Guardian'' newspaper as saying that "there is no good evidence that TM has positive effects on children. The data that exist are all deeply flawed."<ref name="guardian.co.uk">{{cite news| url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2009/apr/14/transcendental-meditation-in-schools | work=The Guardian | location=London | title=Should our schools teach children to 'dive within'? | date=April 14, 2009 | accessdate=March 28, 2010}}</ref> |

A 2003 review by Peter Canter and [[Edzard Ernst]] concluded that evidence does not support a specific or cumulative effect from TM on [[cognitive function]]. The review did find positive results in studies that recruited people with favorable opinions of TM, and used passive control procedures.<ref name="Wien Klin Wochenschr.">{{cite journal |author=Canter PH, Ernst E |title=The cumulative effects of Transcendental Meditation on cognitive function--a systematic review of randomised controlled trials |journal=Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. |volume=115 |issue=21-22 |pages=758–66 |year=2003 |month=November |pmid=14743579 |doi= 10.1007/BF03040500|url= |ref=harv}}</ref> Edzard Ernst, professor of complementary medicine at the Peninsula Medical School in Exeter, was quoted in ''The Guardian'' newspaper as saying that "there is no good evidence that TM has positive effects on children. The data that exist are all deeply flawed."<ref name="guardian.co.uk">{{cite news| url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2009/apr/14/transcendental-meditation-in-schools | work=The Guardian | location=London | title=Should our schools teach children to 'dive within'? | date=April 14, 2009 | accessdate=March 28, 2010}}</ref> |

||

A 2003 research review looked at "well-designed studies" and discussed three randomized controlled trials on students that suggested that TM improves cognitive performance. A study of 154 Chinese high school students found increased practical intelligence, creativity, and speed of information processing. A study of 118 junior high school students replicated the finding, as did a study of 99 vocational school students in Taiwan.<ref name="The Humanistic Psychologist 2003">The Humanistic Psychologist, 2003, 31(2-3) 86–113</ref><ref name="brittonlab.com">Shauna L. Shapiro1, Roger Walsh2, & Willoughby B. Britton3, [http://www.brittonlab.com/publications/Shapiro,%20Walsh,%20Britton%2003.pdf "An Analysis of Recent Meditation Research and Suggestions for Future Directions,"] Journal for Meditation and Meditation Research, 2003, Vol. 3, 69-90</ref> |

A 2003 research review looked at "well-designed studies" and discussed three randomized controlled trials on students that suggested that TM improves cognitive performance. A study of 154 Chinese high school students found increased practical intelligence, creativity, and speed of information processing. A study of 118 junior high school students replicated the finding, as did a study of 99 vocational school students in Taiwan.<ref name="The Humanistic Psychologist 2003">The Humanistic Psychologist, 2003, 31(2-3) 86–113</ref><ref name="brittonlab.com">Shauna L. Shapiro1, Roger Walsh2, & Willoughby B. Britton3, [http://www.brittonlab.com/publications/Shapiro,%20Walsh,%20Britton%2003.pdf "An Analysis of Recent Meditation Research and Suggestions for Future Directions,"] Journal for Meditation and Meditation Research, 2003, Vol. 3, 69-90</ref> |

||

A 2006 systematic review by the [[Cochrane collaboration]] found that there was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding the effectiveness of meditation for anxiety disorders. The review found that, as of 2006, two randomized controlled trials had been done on this topic, one of which was on TM, and concluded that meditation is equivalent to relaxation therapy.<ref name=Cochrane06>{{cite journal |author=Krisanaprakornkit T, Krisanaprakornkit W, Piyavhatkul N, Laopaiboon M |title=Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders |journal=Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |volume= |issue=1 |pages=CD004998 |year=2006 |pmid=16437509 |doi=10.1002/14651858.CD004998.pub2 |ref=harv}}</ref> Other research reviews cite a 1989 meta-analysis of 146 studies that found that relaxation techniques for anxiety had a medium effect size and that Transcendental Meditation had a significantly larger effect.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Manzoni GM, Pagnini F, Castelnuovo G, Molinari E |title=Relaxation training for anxiety: a ten-years systematic review with meta-analysis |journal=BMC Psychiatry |volume=8 |issue= |page=41 |year=2008 |pmid=18518981 |pmc=2427027 |doi=10.1186/1471-244X-8-41 |ref=harv}}</ref><ref>Yin Paradies, "A Review of Psychosocial Stress and Chronic Disease for 4th World Indigenous Peoples and African Americans," Ethnicity & Disease, Volume 16, Winter 2006, p. 305</ref> |

|||

===Criminal rehabilitation, addiction=== |

===Criminal rehabilitation, addiction=== |

||

Revision as of 00:44, 29 July 2010

The Transcendental Meditation or TM technique is a form of mantra meditation introduced in India in 1955[1][2][3][4] by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1917–2008).[5] Taught in a standardized, seven-step course over 4 days by certified teachers, it involves the use of a sound or mantra and is practiced for 15–20 minutes twice per day, while sitting comfortably with closed eyes.[6][7] The fees of learning the technique vary from country to country. In the United States for example, the fee is $1,500, while prices in the United Kingdom (UK) are based on a tiered system, dependent on income.

In 1957, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi began a series of world tours during which he introduced and taught his meditation technique.[8] In 1959, he founded the International Meditation Society and, in 1961, he began to train teachers of the technique.[8][9] From the late 1960s through the mid 1970s, both the Maharishi and TM received significant public attention in the USA, especially among the student population.[10][11] During this period, a million people learned the technique, including well-known public figures.[10] By 1998, the global TM organization had taught an estimated four million people, had 1,000 teaching centers, and owned property assets valued at $3.5 billion.[12]

TM has been reported to be one of the most widely practiced meditation techniques, and among the most widely researched,[13][14][15][16]. Over 200 scientific studies published in peer review journals have examined the effects of the technique[17]

A 2007 review of Transcendental Meditation reported that the definitive health effects of meditation cannot be determined as the bulk of scientific evidence examined was of poor quality.[18] A 2006 Cochrane review found that TM was equivalent to relaxation therapy for the treatment of anxiety.[19]

The Maharishi developed the Science of Creative Intelligence (SCI), a system of theoretical principles to underlie his meditation technique. James Randi, author and skeptic, says SCI has "no scientific characteristics".[20]

In the mid-1970s, the Transcendental Meditation program was expanded to include an "advanced form", the TM-Sidhi program. The TM movement said the advanced techniques could give practitioners super-normal powers, including levitation, that could generate a peace-inducing field.[7][21]

Transcendental Meditation is part of the Maharishi Vedic Approach to Health[22] and is made available worldwide by a number of organizations sometimes collectively referred to as the Transcendental Meditation movement. Transcendental Meditation is a registered trademark of the Maharishi Foundation.[23]

Astronomer Carl Sagan writes that the 'Hindu doctrine' of TM is a pseudoscience.[24] Transcendental Meditation was held to be a religion by three different United States courts in two separate cases: Malnak v. Yogi (1977 and 1979) and Hendel v. World Plan Executive Council (1996).

History

According to religious scholar Kenneth Boa in his book, Cults, World Religions and the Occult, Transcendental Meditation is rooted in the Vedantic School of Hinduism, "repeatedly confirmed" in the Maharishi's books such as the Science of Being and the Art of Living and his Commentary on the Bhagavad Gita.[25] Boa writes that Maharishi Mahesh Yogi "makes it clear" that Transcendental Meditation was delivered to man about 5,000 years ago by the Hindu god Krishna. The technique was then lost, but restored for a time by Buddha. It was lost again, but rediscovered in the 9th century AD by the Hindu philosopher Shankara. Finally, it was revived by Brahmananda Saraswati (Guru Dev) and passed on to the Maharishi.[26]

George Chryssides similarly states that the Maharishi and Guru Dev were from the Shankara tradition of advaita Vedanta.[27] Peter Russell in The TM Technique says that the Maharishi believed that from the time of the Vedas, this knowledge cycled from lost to found multiple times, as is described in the introduction of the Maharishi's commentaries on the Bhagavad-Gita. Revival of the knowledge recurred principally in the Bhagavad-Gita, and in the teachings of Buddha and Shankara.[28] Chryssides notes that, in addition to the revivals of the Transcendental Meditaton technique by Krishna, the Buddha and Shankara, the Maharishi also drew from the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.[27] Vimal Patel also writes that the Maharishi drew from Patanjali when developing the TM technique.[29]

While Transcendental Meditation was originally presented in religious terms during the 1950s this changed to an emphasis on scientific verification in the 1970s. This has been attributed to an effort to improve it's public relations and as an attempt to enable it to be taught public in schools.[30][31]

Principles

Use of a mantra

During the initial, personal instruction session, the student is given a specific sound or mantra along with the technique of how to use the mantra. The sound is utilized as a thought in the meditation process,[32] and as a vehicle that allows the individual's attention to travel naturally to a less active, quieter style of mental functioning.[32][33]

Selection

Lola Williamson states that the mantras used in the Transcendental Meditation technique come from the Tantric tradition, while Russell says the sounds used in the technique are taken from the ancient Vedic tradition.[34][35] Maharishi Mahesh Yogi explains that the selection of a proper thought or mantra "becomes increasingly important when we consider that the power of thought increases when the thought is appreciated in its infant stages of development".[36] The Maharishi says that certain, specific vibrations suit certain people and that this method of meditation enables the mind to experience subtler phases of the vibration until the source of all vibration is experienced.[37]

William Jefferson, in The Story of the Maharishi, explains the importance of the "euphonics" of mantras. Jefferson says that the secrets of the mantras and their subsequent standardization for today's teachers of the technique were unraveled by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi after his years of study with his own teacher, Guru Dev (Brahmananda Saraswati) so that selection is foolproof, and that the number of mantras from the Vedic tradition, which could number in the hundreds, have been brought to a minimum number by the Maharishi.[38]

Author George Chryssides says that, according to the Maharishi, the mantras for "householders" and for recluses differ. The Transcendental Meditation mantras are appropriate mantras for householders, while most mantras commonly found in books are mantras for recluses. Chryssides says that TM teachers claim that the results promised by the Transcendental Meditation technique are dependent on a trained Transcendental Meditation teacher choosing the mantra for the student.[27]

TM meditators are instructed to keep their mantra private. Robert Oates writes that this is a "protection against inaccurate teaching".[39] In his 1997 book, The Sociology of Religious Movements, William Sims Bainbridge wrote that the mantras given for Transcendental Meditation are "supposedly selected to match the nervous system of the individual but actually taken from a list of 16 Sanskrit words on the basis of the person's age".[40]

A list of mantras has been published in various sources, including the January 1984 edition of Omni (magazine), which says it received them from "disaffected TM teachers".[41][42]

Meaning and sound value

Speaking in Kerala, India, in 1955, the Maharishi connected the mantras with personal deities. Similar references can also be found in his later works.[43][44] According to Williamson, the bija or seed mantras used in TM come from the Tantric, rather than Vedic tradition. In the Tantric tradition, these mantras are associated with specific deities and used as a form of worship.[45] At other times, the Maharishi stated that "The theory of mantras is the theory of sound."[44]

In the 1977 court case Malnak vs. Yogi (see below), an undisputed fact in the case was that the mantras are meaningless sounds.[46]

The 1995 expanded edition of Conway and Siegelman's Snapping: America's Epidemic of Sudden Personality Change describes a teacher of Transcendental Meditation who says: "I was lying about the mantras — they were not meaningless sounds; they were actually the names of Hindu demigods - and about how many different ones there were — we had sixteen to give out to our students".[47]

In his book, Alternative Religions: A Sociological Introduction, sociologist Stephen J. Hunt says that the mantra used in the Transcendental Meditation technique has no meaning but that the sound itself is sacred.[33]

Philosophy of science scholar Jonathan Shear, in his book The Experience of Meditation: Experts Introduce the Major Traditions, characterizes the mantras used in the TM technique as independent of meaning associated with any language, and are used for their mental, sound value alone.[48] Fred Travis, Professor of Maharishi Vedic Science at Maharishi University of Management, writes in a 2009 article published in the International Journal of Psychophysiology that "unlike most mantra meditations, any possible meaning of the mantra is not part of Transcendental Meditation practice".[49]

Science of Creative Intelligence

The Science of Creative Intelligence (SCI) is the system of theoretical principles that underlie the technique of Transcendental Meditation. SCI describes "pure creative intelligence" as the basis of all life, and Transcendental Meditation as a means to contact the field of creative intelligence, and according to the theory, realize life's full potential.[50][51] The TM organization describes the Science of Creative Intelligence as both theoretical and practical. Peter Russell, in the TM Technique, describes SCI as an in-depth exploration and understanding of the TM technique. Russell goes on to describe SCI as the interface between the subjective experience or subjective knowledge attributed to practice of the Transcendental Meditation technique, and the objective experience of the various fields of knowledge.[52] SCI, introduced by the Maharishi, has been called his "unified theory of life"[53] and "the science of expansion of awareness or the science of progress in life".[54] An official TM website describes it as "the systematic study of the field of pure creative intelligence, the Unified Field of all the Laws of Nature, and the principles by which it governs the coexistence and evolution of all systems in Nature".[55] "Science of Creative Intelligence" has sometimes been used as a synonym or alternate name for "Transcendental Meditation".[56]

SCI theory is taught in a 33-lesson video course, while the practical aspect is the experience of the TM technique itself.[57] The Independent describes how children are taught SCI at a Maharishi School in the U.K. where they learn principles that include "the nature of life is to grow" and "order is present everywhere".[58]

In 1961, the Maharishi created the "International Meditation Society for the Science of Creative Intelligence".[59] An official chronology lists 1971 as "Maharishi's Year of Science of Creative Intelligence". According to Cynthia Humes in Gurus In America, the shift towards science and away from spiritualism started around 1970.[60] The Second International Symposium on the Science of Creative Intelligence was held in 1971 at the Humboldt State University campus in California, attended by a small number of scientists that included a Nobel Prize-winner.[61] The following year, 1972, the Maharishi developed a World Plan to spread SCI across the world.[62] KSCI, a UHF television station in San Bernardino, California, was started in 1974 to broadcast the TM movement's "educational program".[63]

Courses on the Science of Creative Intelligence were offered in the early 1970s at universities such as Stanford, Yale, the University of Colorado, the University of Wisconsin, and Oregon State University.[64] Degrees in SCI have been awarded by Maharishi University of Management (MUM) in Iowa[53] and Maharishi European Research University (MERU) in Switzerland. Classes at MUM present topics such as art, economics, physics, literature, and psychology in the context of SCI.[65][66] For most of its history, MUM required all students to begin by taking a class in the Science of Creative Intelligence that included 33 videotaped-lectures by the Maharishi,[67][68][69] but by 2009, it was only required of graduate students.[70] The president of MUM credits SCI with the success of its graduates.[71] Individuals who have earned master's or doctoral degrees in the Science of Creative Intelligence include Bevan Morris,[72] Doug Henning,[73] Mike Tompkins,[74] Benjamin Feldman the Finance Minister for Global Country of World Peace,[75] John Gray,[76] and David R. Leffler. SCI is also on the curriculum of lower schools including the Maharishi School of the Age of Enlightenment in Iowa, Wheaton, Maryland,[77] and Skelmersdale, UK.[78]

Theologian Robert M. Price, writing in the Creation/Evolution Journal (the journal of the National Center for Science Education), compares the Science of Creative Intelligence to Creationism.[51] Price says instruction in the Transcendental Meditation technique is "never offered without indoctrination into the metaphysics of 'creative intelligence'".[51] Skeptic James Randi says SCI has "no scientific characteristics",[20] and in a 1982 book, says that TM's claims are no more substantiated by scientific investigation than other mystical philosophies.[79] Astrophysicist and skeptic Carl Sagan writes that the 'Hindu doctrine' of TM is a pseudoscience.[24] Irving Hexham, a scholar of New Age and new religious movements, describes the TM teachings as "pseudoscientific language that masks its religious nature by mythologizing science".[59] Neurophysiologist Michael Persinger writes that "science has been used as a sham for propaganda by the TM movement".[80][81] Sociologists Rodney Stark and William Sims Bainbridge describe the SCI videotapes as being largely based on the Bhagavad Gita, and say that they are "laced with parables and metaphysical postulates, rather than anything that can be recognized as conventional science".[66] Paul Mason suggests that the scientific terminology used in SCI is an academic bias developed to favour scientific terminology, and was a restructuring of the Maharishi's philosophies in terms that would gain greater acceptance and hopefully increase TM technique initiations.[82] In the court case Malnak v Yogi, SCI was held to be a religion.[50]

Teaching procedure

The Transcendental Meditation technique is taught in a standardized, seven-step course[6] that consists of two introductory lectures, a personal interview, and four, two-hour, instruction sessions given on consecutive days.[83][84][85] The initial personal instruction session begins with a short puja ceremony performed by the teacher, after which the student is taught the technique. During the puja ceremony, the teacher recites text in Sanskrit, part of which has been translated as:

Whosoever remembers the lotus-eyed Lord gains inner and outer purity. To Lord Naryan, to Lotus-born Brahman the creator, to Vaishistha, to Shakti, to Shankaracharya the emancipator, hailed as Krishna, to the Lord I bow down and down again. At whose door the whole galaxy of gods pray for perfection day and night.[86]

Walter Martin notes that in learning the Transcendental Meditation technique it is only after this ceremony has been performed that the student receives the mantra.[87] Following initiation, the student practices the technique twice a day. Subsequent group sessions with the teacher ensure correct practice. Step five verifies the correctness of the practice and give further instruction; step six teaches the mechanics of the TM technique based on his/her personal experiences; and, step seven explains the higher stages of human development per this system of meditation.[6]

The technique is practiced morning and evening for 15–20 minutes each time, but is not recommended before bed.[10][84] According to Russell and the official TM web site, the Transcendental Meditation technique can be learned only from a certified, authorized teacher.[28][88]

According to the movement, four to six million people have been trained in the TM technique since 1959. Notable practitioners include The Beatles, David Lynch, John Hagelin, Deepak Chopra, and Mia Farrow. For more names, see List of Transcendental Meditation practitioners.

Fees

From 1967 to 1968, the fees for instruction in the UK, the US, and Australia were variable, ranging from the equivalent of one-week's salary to a flat fee of $35 for students.[89][90][91] By 1975, fees in the US were fixed at $125 for adults, but with discounted rates for students or families.[92] At the time, author John White wrote that fees were "becoming exorbitant", that TM instruction should be free, or at least much cheaper, and that a lot of people question paying $125 for six hours of instruction.[93] Fees rose to $400 for adults and $135 for students in the US and Canada by 1993, and then were increased to $1,000 for adults and $600 for students in 1994.[94][95] In Britain, TM cost £490 (£290 for students) in 1995.[96] By 2003, fees in the US were $2,500.[97] In Bermuda, where fees had been kept below the international average for many years, a 2003 directive from TM Movement headquarters to increase prices from $385 to $2,000 was partly responsible for the suspension of TM instruction there. A former instructor was critical of the fees for excluding ordinary people and making TM something exclusively for the wealthy.[98] In January 2009, The Guardian reported that the expensive fees for TM instruction had "risked it being priced into oblivion" until David Lynch convinced the Maharishi to "radically reduce" fees so as to permit more young people to learn TM.[99]

In 2009, fees in the US were reduced for a one-hour-a-day, four-day course to $1,500 for the general public and $750 for college students.[100][101] Fees in the UK were also reduced, and a tiered fee structure introduced, ranging from £290 to £590 for adults, and £190 to £290 for students, depending on income.[102] The Maharishi was criticized by other Yogis and stricter Hindus for charging fees for instruction in TM, who contended that it was unethical, amounting to the selling of "commercial mantras".[103][104][105]

Supplemental techniques

"Rounding" is a more intensive meditation process taught as part of Residence Courses.[106] A round consists of a sequence of yoga postures called asanas, breathing techniques called pranayama, a standard TM meditation routine and rest. Each round takes about 50 minutes and is then repeated several times.[107] Rounding is said to be especially effective in facilitating "unstressing" in the practitioner. Unstressing is a release of tension in which deep relaxation may be accompanied by physical and emotional effects, including insomnia, anxiety, headaches, and spontaneous imagery.[108]

The movement also teaches, for additional fees in the thousands of dollars, "advanced techniques" of Transcendental Meditation, introduced by the Maharishi in the mid-1970s when new enrollment in Transcendental Meditation collapsed. The TM-Sidhi program, introduced in 1975, expanded the number of offerings.[40][44][109] This later program teaches that, through the power of meditation, one is able to gain various "signposts" of spiritual progress, such as the powers of levitation and invisibility, walking through walls, colossal strength, ESP, perfect health and immortality, among others.[7] The Maharishi has said that "thousands" have learned to levitate.[110] James Randi however, after investigation concludes that there is "no levitation, no walking through walls, no invisibility".[110]

Research

Health outcomes

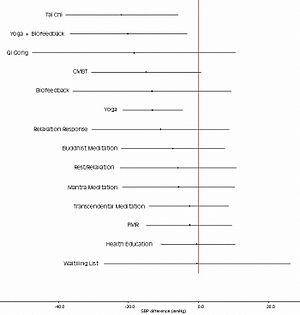

A 2007 government report and meta-analyses found that the effects of TM are no greater than health education regarding blood pressure, body weight, heart rate, stress, anger, self-efficacy, cholesterol, dietary intake, or level of physical activity in hypertensive patients.[112] The report found that compared to progressive muscle relaxation, TM produced a greater reduction in blood pressure.[113] The report also analyzed studies that compared TM to no treatment. In these studies, TM did not produce significantly greater benefits on blood pressure but did produce improvement in cholesterol levels and verbal creativity. In studies that compared TM to a wait-listed control group, TM resulted in greater reduction in blood pressure. The report's assessment of before-and-after studies on patients with essential hypertension found a reduction in blood pressure after practicing TM.[114] The review concludes that firm conclusions regarding health effects cannot be drawn due to the poor quality of the research, though TM researchers said an inappropriate method of quality assessment was used.[115][116]

A 2007 review said that data from two studies found reduced mortality from all causes over a mean period of 8 years in subjects practicing Transcendental Meditation compared to controls. The review said that this finding is consistent with a study that found improved blood pressure, insulin resistance, and cardiac autonomic-nervous-system tone in subjects with cardiovascular disease. The study concluded that, "Findings regarding the effects of psychosocial interventions on disease processes, morbidity and mortality are not yet well established and require appropriate clinical trials."[117]

A 2008 meta-analysis of nine studies found a 4.7 mmHg systolic blood pressure and 3.2 mmHg diastolic blood pressure decrease in those who practiced TM compared to control groups that included health education. Three of the studies were assessed as good quality, three as acceptable, and three suboptimal.[118] The review and its primary author were partially funded by Howard Settle,[118] a proponent of TM.[119] A 2007 meta-analysis by researchers at Maharishi University of Management and the University of Kentucky found that TM lowers blood pressure. The results differed from the 2007 government report mentioned above because the authors removed overlapping studies, corrected data collection errors, and included studies outside the scope of that report.[120][121]

A 2009 review of 16 pediatric studies on meditation done in a school setting that included 6 studies on Transcendental Meditation reported that randomized controlled trials on Transcendental Meditation found a reduction in blood pressure and improvement in vascular function relative to health education. A randomized controlled trial on psychosocial and behavioral outcomes that compared TM to health education found that the TM group had decreased absentee periods, rule infractions, and suspension days, but found no difference in the TM and control groups in regard to tardiness, lifestyle, or stress. The review concluded that sitting meditation "seems to be an effective intervention in the treatment of physiologic, psychosocial, and behavioral conditions among youth."[122] Of the 16 studies included in the review, 5 were uncontrolled. The review said that because of limitations of the research, larger-scale and more demographically diverse studies need to be done to clarify treatment efficacy.[122]

Mental function

A 2010 review by the Cochrane collaboration was unable to draw any conclusions regarding the effectiveness of meditation therapy ( including TM ) for ADHD due to the lack of suitable evidence.[123] A 2006 review by the Cochrane collabortion found that there was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions regarding the effectiveness of meditation for anxiety disorders. The review found that, as of 2006, two randomized controlled trials had been done on this topic, one of which was on TM, and concluded that meditation is equivalent to relaxation therapy.[19]

A 2003 review by Peter Canter and Edzard Ernst concluded that evidence does not support a specific or cumulative effect from TM on cognitive function. The review did find positive results in studies that recruited people with favorable opinions of TM, and used passive control procedures.[124] Edzard Ernst, professor of complementary medicine at the Peninsula Medical School in Exeter, was quoted in The Guardian newspaper as saying that "there is no good evidence that TM has positive effects on children. The data that exist are all deeply flawed."[125]

A 2003 research review looked at "well-designed studies" and discussed three randomized controlled trials on students that suggested that TM improves cognitive performance. A study of 154 Chinese high school students found increased practical intelligence, creativity, and speed of information processing. A study of 118 junior high school students replicated the finding, as did a study of 99 vocational school students in Taiwan.[126][127]

Criminal rehabilitation, addiction

Transcendental Meditation has been used in correctional settings, and research has shown a reduction in negative psychological states and recidivism — that is, returning to criminal behavior after being released from prison. According to a 2010 research review, studies involving hundreds of prisoners at San Quentin and Folsom State Prisons in California and Walpole State Prison in Massachusetts found that recidivism rates were reduced by as much as 47%. Overall, the TM prisoners at Folsom were 43% less likely to return to prison compared to control groups. The study at Folsom also looked at anxiety measures and found a sharp reduction compared to controls. The review said that meditation studies may be subject to researcher bias and self-selection bias, but concluded that policy makers and prison officials may want to implement meditation programs in prisons.[128]

A 2009 review looked at the effect of TM on addiction and noted that while many studies exist, they were conducted by researchers affiliated with Transcendental Meditation and were not randomized controlled trials. Thus the evidence for treating addictive disorders is speculative and inconsistent.[129] It said that while the quasi-religious aspects and cost may deter people, the simplicity of the technique, the physiological changes it induces, and the apparent effectiveness in nonpsychiatric settings merit further study and that "the theoretical basis for meditation’s role in addressing substance use disorders is compelling" based on the physiological mechanisms that have been found.[129] According to the Cambridge Textbook of Effective Treatments in Psychiatry, a randomized controlled trial that included the use of Transcendental Meditation in treating alcoholism found that TM and biofeedback increased abstinence in alcoholics. The textbook concluded that there is not yet sufficient evidence for use as treatment but that meditation can help alcoholic patients in a variety of ways.[130]

Effects on the brain

Transcendental Meditation has been found to produce specific types of brain waves as measured by electroencephalography (EEG). Studies have found that, compared to a baseline, during meditation there is an increase in alpha amplitude followed by a slowing of the alpha frequency and the spread of this to the frontal cortex.[131] Alpha brain waves are classically viewed as reflecting a relaxed brain.[131] When compared to control groups using a different relaxation technique, the increase in alpha is similar and integrated alpha amplitude may even decrease compared to a baseline of eyes-closed rest.[132]

Transcendental Meditation also produces alpha coherence, that is, large-scale integration of frequencies in different parts of the brain.[131] This pattern is also sometimes seen while a subject is actively focusing his or her attention on an object or holding some information in mind. These brain patterns generally suggest a decrease in mental activity and are associated with a relaxed state.[132] According to the Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness, TM promotional material has said that this coherence represents a more orderly state of the brain and one that is unique to TM.[133] The Cambridge Handbook says that these claims may be overstated or premature. "Because alpha rhythms are ubiquitous and functionally non-specific, the claim that alpha oscillations and alpha coherence are desirable or are linked to an original and higher state of consciousness seem quite premature" and "alpha frequencies frequently produce spontaneously moderate to large coherence (0.3-0.8 over large inter-electrode distance.) The alpha coherence values reported in TM studies, as a trait in the baseline or during meditation, belong to this same range. Thus a global increase of alpha power and alpha coherence might not reflect a more 'ordered' or 'integrated' experience, as frequently claimed in TM literature, but rather a relaxed, inactive mental state."[133]

EEG studies have shown an increase in theta waves and a dominant pattern of alpha waves in the frontal and occipital lobes.[129] Other EEG measurements that show neuronal hypersynchrony are similar to those found in epilepsy, leading to concerns about the potential risk of kindling of epilepsy from repetitive Transcendental Meditation.[7] Other studies have found meditation to be a possible antiepileptic therapy, leading to calls for more research.[7]

A 1999 paper by Lachaux et al. suggests that EEG coherence may be a less useful measurement[134] since it does not separate the effects of amplitude and phase in the interrelations between two EEG signals.

Effects on the physiology

TM has been found to produce a set of characteristic responses such as reduced respiration, decreased breath volume, decreased lactate and cortisol (hormones associated with stress), increased basal skin resistance, and slowed heartbeat.[129][124] The mechanism for the effects of TM has been explained by proponents as being due to greater order in the physiology, decreased stress, and growth of creative intelligence.[124]

Research quality

Various research reviews have identified some studies as being well-designed, rigorous, or high quality.[118][126] Popular media and scholars have found problems with the body of research. According to newspaper reports and the Encyclopedia of Occultism & Parapsychology, some of the research has been "criticized for bias and a lack of scientific evidence",[135] for "methodological flaws, vague definitions, and loose statistical controls",[136] and for "failing to conduct double-blind experiments" and for "influencing test results with the prejudice of the tester".[137] Articles in the Jerusalem Post and Wall Street Journal, and a review by Canter and Ernst (2004), said that many studies appear to have been conducted by devotees or researchers at universities tied to the Maharishi, including Maharishi University of Management in Iowa and Maharishi European Research University in Switzerland,[124][138][139] which is disputed by Orme-Johnson, who cites the number of institutions worldwide where the research has been conducted.[140] He also says that a meta-analyses of studies on TM and anxiety found that those studies done by researchers with no connection to TM showed a slightly larger effect than those studies by researchers who had a connection.[141]

According to TM researchers, studies on Maharishi Vedic Approach to Health have been conducted at over 200 different research institutions and universities in over 30 countries worldwide.[142] Maharishi Ayurveda practitioner Roger A. Chalmers has compiled a list of 341 studies on TM that he says were published in "independent peer-reviewed journals or other edited scientific publications".[143] Many hundreds of the 700 studies on TM have been produced by researchers directly associated with the TM movement and/or had not been peer reviewed, according to a 2003 review that looked at the effects of TM on cognitive function and an article in Student BMJ.[124][144]

A 2004 review by Canter and Ernst said that the published studies had important methodological weaknesses and were potentially biased by the affiliation of authors to the TM organization.[145] It concluded that there was "insufficient good-quality evidence to conclude whether or not TM has a cumulative positive effect on blood pressure". In response, TM researchers said that most of the studies in the review were funded by various institutes of the National Institutes of Health and that, as such, the methodologies were peer-reviewed by experts.[142]

A 2007 U.S. government-sponsored review of research on meditation, including Transcendental Meditation, yoga, tai chi, qi gong, mindfulness, and others, said that firm conclusions on health effects cannot be drawn, as the majority of the studies are of poor methodological quality.[18] The review included studies on adults through September 2005, with a particular focus on research pertaining to hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and substance abuse.[146] The review used the Jadad scale to assess quality of the studies using control groups and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for the others. The quality assessment portion of the 2007 review was published in 2008. The article stated that "Most clinical trials on meditation practices are generally characterized by poor methodological quality with significant threats to validity in every major quality domain assessed". The authors found that there was a statistically significant increase in the quality of all reviewed meditation research, in general, over time between 1956-2005. Of the 400 clinical studies, 10% were found to be good quality. A call was made for rigorous study of meditation.[147] These authors also noted that this finding is not unique to the area of meditation research and that the quality of reporting is a frequent problem in other areas of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) research and related therapy research domains.

TM researchers said that the 2007 review suffered from various limitations related to data collection, analysis, and reporting procedures.[148] TM researcher David Orme-Johnson said that the use of double blinding, which is required by the Jadad scale, is not appropriate to meditation research and that the review failed to assess more relevant determinants of research quality.[149] Research reviews in science journals say that double blinding may not be possible in meditation research,[150][151][152][153][154]One of the earliest double-blinded placebo studies of Transcendental Mediation was conducted in 1975[155], but a 2007 review by TM researchers found this study, and none of the over-800 studies reviewed, were properly double-blinded. They say it is evidence that double blinding may not be possible.[156]

Research funding, publication, and promotion

In 1999, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine awarded a grant of nearly $8 million to Maharishi University of Management to establish the first research center specializing in natural preventive medicine for minorities in the U.S.[157] The research institute, called the Institute for Natural Medicine and Prevention (INMP), was inaugurated on October 11, 1999, at the University's Department of Physiology and Health in Fairfield, Iowa.[158] By 2004, the U.S. government had awarded more than $20 million to Maharishi University of Management to fund research.[159]

In 2009, the National Institutes of Health awarded an additional grant of $1,000,000 distributed over two years for research on the use of TM in the treatment of coronary heart disease in African-Americans. The award was for research in collaboration with the INMP and Columbia University Medical Center in New York City. The award was from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 via the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.[160]

Research on Transcendental Meditation has been published in medical journals such as Archives of Internal Medicine[161] (a journal of the American Medical Association), Stroke[162] (a journal of the American Heart Association), Hypertension[163] (a journal of the American Heart Association), the American Journal of Hypertension,[164][165][166] the American Journal of Cardiology,[167] and the International Journal of Psychophysiology.[168]

Leading individuals and organizations associated with TM cite the existence of many studies, "more than 600 published research studies, conducted at over 200 independent research institutions in 33 countries",[169] to support TM-related concepts.[170][171] The quantity of studies have been cited to support the political programs of the Natural Law Party,[172][173] the tax status of a TM institution,[174] the use of TM to rehabilitate prisoners,[175] the teaching of TM in schools,[176] the issuance of bonds to finance the movement,[177] as proof that TM is a science rather than a religion,[178] to show the efficacy of the Maharishi Vedic Approach to Health,[142] and as a reason to practice TM itself.[179]

Maharishi Vedic approach to health

Transcendental Meditation is part of the Maharishi Vedic Approach to Health (MVAH).[22] MVAH (also known as Maharishi Ayurveda[180][181] and Maharishi Vedic Medicine[182]) was founded in the mid 1980s by the Maharishi. MVAH is considered an alternative medicine and aims at being a complementary system to modern western medicine.[183] It is based on Ayurveda, a system of traditional medicine developed in India in ancient times.

Maharishi Effect

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi predicted that the quality of life for an entire population would be noticeably improved if one percent of the population practiced the Transcendental Meditation technique. This is known as the "Maharishi Effect".[184] With the introduction of the TM-Sidhi program including Yogic Flying, the Maharishi proposed that only the square root of 1% of the population practicing this advanced program would be required to create benefits in society, and this was referred to as the "Extended Maharishi Effect".[185]

Practice of the TM and TM-Sidhi programs has been credited by the TM organization with the fall of the Berlin Wall, a reduction in global terrorism, a decrease in the rate of inflation in the US, the lowering of crime rates, and other positive effects.[186] The Maharishi Effect has been endorsed by the former President of Mozambique Joaquim Chissano, who applied this technology in his country,[187] and positive results have been reported in 42 independent scientific studies.[188] Some have described this research as "pseudoscience".[189] James Randi followed up on some of the claims attributed to the Maharishi Effect that Maharishi International University of faculty member Robert Rabinoff made at a talk in Oregon in 1978 attended by Ray Hyman. Randi spoke to the Fairfield Chief of Police who had not experienced any drop in crime rate and the regional Agriculture Department whose statistics on yield showed no difference between Jefferson County and the state average.[190]

According to a follower, the Maharishi said that "the earth yields up its treasures" when the one percent threshold is met.[191]

Views on human development

According to Vimal Patel, a pathologist at Indiana University, TM has been shown to produce states that are physiologically different from waking, dreaming and sleeping.[29] Maharishi Mahesh Yogi says in his 1963 book, The Science Of Being and Art Of Living, that, over time, the practice of allowing the mind to experience its deeper levels during the Transcendental Meditation technique brings these levels from the subconscious to within the capacity of the conscious mind. According to the Maharishi, as the mind quiets down and experiences finer thoughts, the Transcendental Meditation practitioner can become aware that thought itself is transcended and can have the experience of what he calls the 'source of thought', 'pure awareness' or 'transcendental Being'; 'the ultimate reality of life'.[32][192][193] TM has been described by the movement as a technology of consciousness.[33]

Girish Varma, a Brahmachari who heads the Maharishi Vidya Mandir school system and is a nephew of the Maharishi, says that scientific studies have shown that practitioners can achieve divine powers through TM.[194]

Seven States of Consciousness

According to the Maharishi there are seven levels of consciousness: (i) waking; (ii) dreaming; (iii) deep sleep; (iv) Transcendental or Pure Consciousness; (v) Cosmic Consciousness (Skt: turiyatita); (vi) God Consciousness (Skt: bhagavat-chetana); and (vii) Supreme knowledge, or unity consciousness (Skt: brahmi-chetana). The Maharishi says that the fourth level of consciousness (Skt: turiya) can be experienced through Transcendental Meditation, and that the fifth state can be achieved by those who meditate diligently. The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness says that it may be premature to say that the EEG coherence found in TM is an indication of a higher state of consciousness.[195] A sign of cosmic consciousness is “ever present wakefulness” that is present even during sleep.[196] Research on individuals experiencing cosmic consciousness as a result of practice of TM has found EEG profiles, muscle tone measurements, and REM indicators that suggest there is physiological evidence of this higher state.[126][127][197]

School programs

- For schools belonging to the Transcendental Meditation movement, see Educational institutions

TM in public schools in 1970s : Malnak v. Yogi

As of 1974, 14 states encouraged local schools to teach TM in the classroom, and it was taught at 50 universities.[198] Among the public school systems where TM was taught were Shawnee Mission, Kansas,[199] Maplewood, Paterson, Union Hill and West New York, New Jersey,[200] Eastchester, New York[198][201] and North York, Ontario.[202]

In 1979, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the 1977 decision of the US District Court of New Jersey that a course in Transcendental Meditation and the Science of Creative Intelligence (SCI) was religious activity within the meaning of the Establishment Clause and that the teaching of SCI/TM in the New Jersey public high schools was prohibited by the First Amendment.[203][204] The court ruled that, although SCI/TM is not a theistic religion, it deals with issues of ultimate concern, truth, and other ideas analogous to those in well-recognized religions. The court found that the religious nature of the course was clear from careful examination of the textbook, the expert testimony elicited, and the uncontested facts concerning the puja ceremony, which it found involved "offerings to deities as part of a regularly scheduled course in the schools' educational programs".[205] State action was involved because the SCI/TM course and activities involved the teaching of a religion, without an objective secular purpose.[204]

The Malnak decision resulted in the dismantling of the Maharishi's programs to establish Transcendental Meditation in the public schools with governmental funding.[44]

1990s–present : Charter School and "Quiet Time" programs

In recent years, TM is being used in schools, with some governmental sponsorship.[44] A number of public charter schools began introducing Transcendental Meditation programs beginning in the 1990s. These include:

- The Ideal Academy Public Charter School (1996) with the approval of the Washington, D.C. Board of Education.[208][209] The 2005-2006 pilot project at Ideal Academy was conducted along with research to document the effects of the program.[206]

- The Nataki Talibah Schoolhouse in Detroit (1996). The program was featured on the Today Show in 2003.[210] The school has since been classified by the Skillman Foundation as a "High-Performing Middle School".[211] Over the years, the program at Nitaki Talibah has been funded by various foundations including General Motors, Daimler Chrysler, the Liebler Foundation and more recently, the David Lynch Foundation.

Since 2005, the David Lynch Foundation has promoted and provided funding for the teaching of TM in schools.[212] It subsidizes the cost for training a student in TM, which was $650 per year as of 2004 in the US.[213] In 2006, six public schools were each awarded $25,000 by the David Lynch Foundation to begin a TM program.[214] By 2006, twenty five public, private, and charter schools in the United States had offered Transcendental Meditation to their students.[208] The Lowel Whiteman Primary School in Steamboat Springs, Colorado began using Transcendental Meditation in their school in 2008.[215][clarification needed]

Efforts to re-introduce Transcendental Meditation into public schools have resulted in increased tensions because it is viewed by some parents and critics as an overstepping of boundaries.[45] Some parents have opposed these efforts based on concerns that it may lead to "lifelong personal and financial servitude to a corporation run by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi".[212] In 2006, the Terra Linda High School in San Rafael, California canceled plans for Transcendental Meditation classes due to concerns of parents that it would be promoting religion.[216]

According to a 2008 Newsweek article, critics believe that Transcendental Meditation is a repackaged, Eastern, religious philosophy that should not be used in public schools. Advocates say that Transcendental Meditation is purely a mechanical, physiological process.[209] University of South Carolina sociologist Barry Markovsky describes teaching the Transcendental Meditation technique in schools as "stealth religion".[217] According to Barry Lynn, executive director of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, Transcendental Meditation is rooted in Hinduism and, when introduced into public schools, it crosses the same constitutional line as in the Malnak case and decision of 1979. In May 2008, Lynn said that the Americans United for Separation of Church and State is keeping a close legal eye on the TM movement and that there are no imminent cases against them.[209][218] Brad Dacus of the Pacific Justice Institute says doing Transcendental Meditation during a school's "quiet time" (a short period many schools have adopted that children use for prayer or relaxation) is constitutional.[209]

According to the TM movement's school in South Africa, Consciousness-Based Education has also been introduced in the Netherlands, Australia, India, Ecuador, Thailand, China, and Great Britain.[219]

Corporate programs

Transcendental Meditation has been utilized in corporations both in the U.S.A and in India. As of 2001, companies such as General Motors helped their salaried employees pay for TM; IBM reimbursed half the TM course fee for its US employees.[220]

The Washington Post reported in 2005 that The Tower Companies, "one of Washington D.C.'s largest real estate development companies", has added classes in Transcendental Meditation to their employee benefit program in order "to contain stress-related ailments and health care costs". Seventy percent (70%) of the employees at The Tower Companies participate in the program.[221][222][223]

A number of Indian companies give their managers training in Transcendental Meditation to reduce stress. These companies include: AirTel, Siemens, American Express, SRF and Wipro, Hero Honda, Ranbaxy, Hewlett Packard, BHEL, BPL, ESPN-Star Sports, Tisco, Eveready, Maruti, and Godrej. All employees at Marico practice Transcendental Meditation in groups as part of their standard workday. According to the Times of India, this practice benefits both employees and employers.[224]

Characterizations

Self characterizations

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi describes Transcendental Meditation as a technique which requires no preparation, is simple to do, and can be learned by anyone.[225] The technique is described as being effortless[226] and natural, involving neither contemplation nor concentration, and relying on the natural tendency of the mind to move in the direction of greater satisfaction.[33][48][49][227]

In his book The TM Technique, Peter Russell, a teacher of Transcendental Meditation who had spent time with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi says, Transcendental Meditation allows the mind to become still without effort, in contrast to meditation practices that attempt to control the mind by holding it on a single thought or by keeping it empty of all thoughts.[28] He says trying to control the mind is like trying to go to sleep at night — if a person makes an effort to fall asleep, his or her mind remains active and restless.[28] This is why, he says, Transcendental Meditation avoids concentration and effort.[28]

According to Wayne Teasdale's book The Mystic Heart: Discovering a Universal Spirituality in the World’s Religions, Transcendental Meditation is what is called an open or receptive method that can be described as giving up control and remaining open in an inner sense.[228]

Anthony Campbell says that because TM is a natural process, its practice requires no "special circumstances or preparations". Campbell writes that Transcendental Meditation is "complete in itself" and does "not depend upon belief" or require the practitioner to accept any theory.[229]

Government

Transcendental Meditation and some of it associated organizations have been described as a religion or a cult. For example, three US courts have held it to be a religion in two cases: Malnak v Yogi (1977 and 1979) and Hendel v World Plan Executive Council (1996). In addition to the 3rd Circuit opinion in Malnak holding that Transcendental Meditation and the Science of Creative Intellingence were religious under the Establishment Clause, in 1996, the Superior Court for the District of Columbia ruled in Hendel v World Plan Executive Council that the practice of Transcendental Meditation and TM-Sidhi Program were a religion and that trial of the fraud and other claims for damages by a former TM and TM-Sidhi practitioner against the World Plan Executive Council and Maharishi International University would involve the Court in excessive entanglement into matters of religious belief contrary to the First Amendment.[199]

A 1980 report by the West German government's Institute for Youth and Society characterized TM as a "psychogroup". The TM organization[who?] sued unsuccessfully to block the release of the report.[2][230] The 1995 report of the Parliamentary Commission on Cults in France listed Transcendental Meditation as a cult.[231] The state of Israel has condemned TM, commonly agreed by anti-cult groups there to be a cult.[232]

Religion

Cardinal Jaime Sin, the Archbishop of Manila, wrote a pastoral statement in 1984 after Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos invited more than 1,000 members of the movement to Manila to reduce dissent through Yogic Flying. Sin said that neither the doctrine nor the practice of TM are acceptable to Christians.[233] In 2003, the Roman Curia, a Vatican council, published a warning against mixing eastern meditation, such as TM, with Christian prayer.[234] Other clergy, including Catholic clergy, have found the Transcendental Meditation to be compatible with their religious teachings and beliefs.[235][236][237] Religion scholar Charles H. Lippy writes that earlier spiritual interest in the technique faded in the 1970s and it became a practical technique that anyone could employ without abandoning their religious affiliation.[238] Bainbridge found Transcendental Meditation to be a "...highly simplified form of Hinduism, adapted for Westerners who did not possess the cultural background to accept the full panoply of Hindu beliefs, symbols, and practices",[40][239] and describes the Transcendental Meditation puja ceremony as "...in essence, a religious initiation ceremony".[40] Metropolitan Maximos of Pittsburgh of the Greek Orthodox Church describes TM as being "a new version of Hindu Yoga" based on "pagan pseudo-worship and deification of a common mortal, Guru Dev".[240]

William Johnston, an Irish Jesuit living in Japan, says that despite its religious origins the TM technique as introduced by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi has no attachments to any particular religion.[241] Former Maharishi University of Management Dean of College of Arts and Sciences, James Grant writes that the Maharishi's techniques for the development of consciousness are non-sectarian and require no belief system.[242] The official TM web site says it is a non-religious mental technique for deep rest.[243] The Maharishi refers to the technique as "a path to God".[244] Andrew Sullivan, political commentator for The Atlantic and an openly gay Roman Catholic, wrote in 2010 that he does not consider his practice of Transcendental Meditation to be a “contradiction of my faith in Christ”.[245][246] Martin Gardner, a mathematician, refers to it as "the Hindu cult".[247]

Douglas Cowan, a Professor of Sociology and Religious Studies, covers Transcendental Meditation in Cults and New Religions along with Scientology, Family Federation for World Peace and Unification (FFWPU), The Children of God, Branch Davidian, Heaven’s Gate, and Wicca.[248][249] Transcendental meditation has been accused of "surreptitiously smuggling in forms of Eastern religion under the guise of some seemingly innocuous form of health promotion".[250]

Transcendental Meditation movement

The Transcendental Meditation movement encompasses initiatives by Marishi Mahesh Yogi spanning multiple fields and across several continents.

The terms "Transcendental Meditation", "TM", and "Science of Creative Intelligence" are servicemarks owned by Maharishi Foundation Ltd., a UK non-profit organization.[251] These servicemarks have been sub-licensed to the Maharishi Vedic Education Development Corporation (MVED), an American non-profit, tax exempt organization which oversees teaching the Transcendental Meditation technique and related courses in the U.S.A.[252][253]

Two entities, the Maharishi School of Vedic Sciences-Minnesota (as a successor to the World Plan Executive Council)[254] in 1997 and the Maharishi Spiritual Center in 2001, were denied tax exempt status because they were found not to be educational organizations.[255]

Transcendental Meditation is taught in the UK by the Maharishi Foundation, a registered educational charity (number 270157).[256] TM is taught in South Africa by teachers registered with Maharishi Vedic Institute — a Non-Profit Organisation, registration number 025-663-NPO.[257] TM is taught in Australia by a registered non-profit educational organisation called "Maharishi's Global Administration through Natural Law Limited".[258]

The Skeptics Dictionary refers to TM as a "spiritual business".[259]

References

- ^ "Beatles guru dies in Netherlands". USA Today. Associated Press. February 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Epstein, Edward, (December 29, 1995). "Politics and Transcendental Meditation". San Francisco Chronicle.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Woo, Elaine (February 6, 2008). "Maharishi Mahesh Yogi; founded Transcedental Meditation movement". Baltimore Sun. reprinted from LA Times

- ^ Morris, Bevan (1992). "Maharishi's Vedic Science and Technology: The Only Means to Create World Peace" (PDF). Journal of Modern Science and Vedic Science. 5 (1–2): 200.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Morris, Bevan; Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (2001). "Forward". Science of Being and Art of Living. New York: Plume/The Penguin Group. ISBN 0452282667.

- ^ a b c "Learn the Transcendental Meditation Technique – Seven Step Program". Tm.org. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ a b c d e Lansky EP, St Louis EK (2006). "Transcendental meditation: a double-edged sword in epilepsy?". Epilepsy Behav. 9 (3): 394–400. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.04.019. PMID 16931164.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Thirty Years Around the World, Volume One, 1957-1964. MVU Press. pp. 213–237. ISBN 90-71750-02-7.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (1992). Encyclopedic handbook of cults in Americ. New York: Garland Pub. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-8153-1140-9.

- ^ a b c "Behavior: THE TM CRAZE: 40 Minutes to Bliss". Time. 1975-10-13. ISSN 0040-718X. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

{{cite news}}: Check|issn=value (help) - ^ "Maharishi Mahesh Yogi; founded Transcendental Meditation movement". Los Angeles Times. 2008-02-06. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ The Times London, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Feb 7 2008, pg 62

- ^ Murphy M, Donovan S, Taylor E. The Physical and Psychological Effects of Meditation: A review of Contemporary Research with a Comprehensive Bibliography 1931-1996. Sausalito, California: Institute of Noetic Sciences; 1997.

- ^ Benson, Herbert; Klipper, Miriam Z. (2001). The relaxation respons. New York, NY: Quill. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-380-81595-1.

- ^ Sinatra, Stephen T.; Roberts, James C.; Zucker, Martin (2007-12-20). Reverse Heart Disease Now: Stop Deadly Cardiovascular Plaque Before It's Too Late. Wiley. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-470-22878-4.

- ^ Travis, Frederick; Chawkin, Ken (Sept-Oct, 2003). New Life magazine.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ MUM official web site with bibliography of the 200+ studies

- ^ a b Ospina p.v

- ^ a b Krisanaprakornkit T, Krisanaprakornkit W, Piyavhatkul N, Laopaiboon M (2006). "Meditation therapy for anxiety disorders". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD004998. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004998.pub2. PMID 16437509.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "James Randi Educational Foundation — An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural".

- ^ Skolnick AA (1991). "Maharishi Ayur-Veda: Guru's marketing scheme promises the world eternal 'perfect health'". JAMA. 266 (13): 1741–2, 1744–5, 1749–50. doi:10.1001/jama.266.13.1741. PMID 1817475.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b John Briganti, testimony to the White House Commission On Complementary And Alternative Medicine Policy, October 31, 2000. [1]

- ^ "Definition of Transcendental Meditation - NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms, Definition of Transcendental Meditation - NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms".

- ^ a b Sagan, Carl (1997). The demon-haunted world: science as a candle in the dark. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 16. ISBN 0-345-40946-9.

- ^ Boa cites Meditations of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi on the Bhagavad-Gita, and The Science of Being and Art of Living.

- ^ Boa, Kenneth (1990). Cults, world religions, and the occul. Wheaton, Ill.: Victor Books. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-89693-823-6.

- ^ a b c Chryssides, George D. (1999). Exploring new religions. London: Cassell. pp. 293–296. ISBN 978-0-8264-5959-6.

- ^ a b c d e Russell, Peter H. (1976). The TM technique. Routledge Kegan Paul PLC. p. 134. ISBN 0-7100-8539-7. Cite error: The named reference "Russell1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Patel, Vimal (1998). "Understanding the Integration of Alternative Modalities into an Emerging Healthcare Model in the United States". in Humber, James M.; Almeder, Robert F.. Alternative medicine and ethics. Humana Press. pp. 55-56. ISBN 0-89603-440-2, 9780896034402. [2]

- ^ Dawson, Lorne L. (2003). Cults and New Religious Movements: A Reader (Blackwell Readings in Religion). Blackwell Publishing Professional. p. 54. ISBN 1-4051-0181-4.

- ^ Chryssides, George D.; Margaret Lucy Wilkins (2006). A reader in new religious movements. London: Continuum. p. 7. ISBN 0-8264-6167-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Phelan, Michael (1979). "Transcendental Meditation. A Revitalization of the American Civil Religion". Archives des sciences sociales des religions. 48 (48–1): 5–20.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c d Hunt, Stephen (2003). Alternative religions: a sociological introduction. Aldershot, Hampshire, England ; Burlington, VT: Ashgate. pp. 197–198. ISBN 978-0-7546-3410-2.

- ^ Williamson, Lola Transcendent in America:Hindu-Inspired Meditation Movements as New ReligionNYU Press, 2010, Page 86 ISBN 0-8147-9450-5, 9780814794500

- ^ Russell, pp. 49-50

- ^ Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1963). The Science of Being and Art of Living. Meridian. p. 51. ISBN 0452282667.

- ^ Meditation of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Bantam Books, 1968, Page 106-107

- ^ Jefferson, William (1976). The Story of The Maharishi. New York: Pocket (Simon and Schuster). pp. 52–53.

- ^ Celebrating the Dawn, Robert Oates, G.P. Putnam's, 1976, P. 194

- ^ a b c d Bainbridge, William Sims (1997). The sociology of religious movements. New York: Routledge. p. 188. ISBN 0-415-91202-4. Cite error: The named reference "Bainbridge" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Transcendental Truth". Omni. Jan 1984. p. 129.

- ^ Scott, R.D. (1978). Transcendental Misconceptions. San Diego: Beta Books. ISBN 0892930314.

- ^ Yogi, Maharishi Mahesh, Beacon Light of the Himalyas 1955, p. 63.

- ^ a b c d e Forsthoefel, Thomas A.; Humes, Cynthia Ann (2005). Gurus in Americ. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7914-6573-8. Cite error: The named reference "Forsthoefel" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Williamson, Lola Transcendent in America:Hindu-Inspired Meditation Movements as New ReligionNYU Press, 2010 ISBN 0-8147-9450-5, 9780814794500

- ^ “Transcendental Meditation, briefly stated, is a technique of meditation in which the meditator contemplates a meaningless sound.” 440 F. Supp. 1288

- ^ Conway, Flo; Siegelman, Jim. (1995). Snapping : America's epidemic of sudden personality chang. New York: Stillpoint Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-9647650-0-9.

- ^ a b Shear, J. (Jonathan) (2006). The experience of meditation : experts introduce the major tradition. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House. pp. 23, 30–32, 43–44. ISBN 978-1-55778-857-3.

- ^ a b Travis F, Haaga DA, Hagelin JS, Tanner M, Nidich S, Gaylord-King C et al. Effects of Transcendental Meditation practice on brain functioning and stress reactivity in college students. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2009 71(2):170-176

- ^ a b Merriman, Scott A., Religion and the Law in America ABC-CLIO, (2007) ISBN 1851098631, 9781851098637 (p 522)

- ^ a b c Price, Robert M. (Winter, 1982). "Scientific Creationism and the Science of Creative Intelligence". Creation Evolution Journal. 3 (1): 18–23.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Russell, Peter. The TM Technique Boston, Mass. Routledge and Keegan Paul, 1976. pg. 148-151

- ^ a b DePALMA, ANTHONY (April 29, 1992). "University's Degree Comes With a Heavy Dose of Meditation (and Skepticism)". New York Times. p. B.8.

- ^ JOHNSON, JANIS (March 31, 1976). "A Court Challenge to TM". the christian CENTURY. pp. 300–302.

- ^ "The Science of Creative Intelligence Course". Maharishi.org. Retrieved May 31, 2010.

- ^ Rabey, Steve (September 17, 1994). "TM disciples remain loyal despite controversies". Colorado Springs Gazette - Telegraph. p. E.2.

- ^ http://www.maharishi.org/sci/sci.html

- ^ Michelle Teasdale, "Mummy, can we meditate now? The Independent, June 3, 2010

- ^ a b Kennedy, John W; Hexham., Irving (January 8, 2001). "Field of TM dreams". Christianity Today. Vol. 45, no. 1. pp. 74–79.

- ^ Humes, Cynthia A (2005). "Maharishi Mahesh Yogi: Beyond the T.M. Technique". Gurus in America. SUNY Press. p. 61. ISBN 079146573X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|first1-editor=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|first2-editor=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|last1-editor=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|last2-editor=ignored (help) - ^ Johnson, =Benton (1992). "On Founders and Followers: Some Factors in the Development of New Religious Movements". Sociological Analysis. Presidential Address — 1987. Vol. 53, no. -S S1-S13.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Melton (2003). "Eastern Family, Part I". Encyclopedia of American Religions. p. 1045. ISBN 0815305001.

- ^ HOLLEY, DAVID (June 5, 1986). "Eclectic TV KSCI's Programming in 14 Languages Offers News, Entertainment, Comfort to Ethnic Communities". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- ^ T. K. Irwin, "What's New in Science: Transcendental Meditation: Medical Miracle or 'Another Kooky Fad,'" Sarasota Herald Tribune Family Weekly, October 8, 1972, pp. 8-9. [3]

- ^ Atlas, James (April 22, 1985). "MAHARISHI U.". The New Republic.

- ^ a b Stark, Rodney (1986). The Future of Religion: Secularization, Revival, and Cult Formation. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 289. ISBN 0520057317.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Barron's Educational Series, Inc. (2000). Profiles of American colleges (24th ed. ed.). Hauppauge N.Y. ;London: Barron's ;;Hi Marketing. ISBN 9780764172946.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Schmidt-Wilk, Jane, Heston, Dennis & Steigard, David, "Higher education for higher consciousness: Maharishi University of Management as a model for spirituality in management education", Journal of Management Education Vol. 24, No. 5, 580-611 (2000)DOI: 10.1177/105256290002400505

- ^ Princeton Review (2006-08-15). Complete Book of Colleges, 2007 Edition. Random House Information Group. ISBN 9780375765575.

- ^ MUM catalog for the Department of Maharishi Vedic Science

- ^ Noble, Alice (May 23, 1982). "Maharishi bucks 'Guru U' image". The HAWK EYE. p. 18.

- ^ Shrimsley, Robert (April 4, 1992). "Election 1992: Somewhere over the rainbow". The Daily Telegraph. London (UK). p. 5.

- ^ LAMB, JAMIE (October 1, 1993). "Will squadron of yogic flyers be our best line of defence?". The Vancouver Sun. p. A.3.

- ^ McHugh, Edward T (August 29, 1992). "Natural Law Party joins race". Telegram & Gazette. Worcester, Mass. p. A.3.

- ^ "The maharishi and transcendental disintermediation". Institutional Investor International Edition. Vol. 28, no. 3. March 2003. pp. 8–11.

- ^ Murphy, Lauren (February 14, 2002). "Mars and Venus at work; Critics aim to bring Gray back down to Earth". Washington Times. p. A.02.

- ^ Buckley, Stephen (March 19, 1993). "This School Offers Readin', 'Ritin' and Mantras". The Washington Post. p. D.01.

- ^ Tolley, Claire (January 12, 2002). "Children meditate on top class GCSEs". Daily Post. Liverpool. p. 13.

- ^ Randi, James (1982). Flim-flam!: psychics, ESP, unicorns, and other delusions. Buffalo, N.Y: Prometheus Books. p. 94. ISBN 0-87975-198-3.

- ^ Harvey, Bob (December 18, 1993). "Establishing Transcendental Meditation's identity; Few can agree if it's a religion, Hinduism or meditation". The Ottawa Citizen. p. C.6.

- ^ Persinger, Michael A.; Carrey, Normand J.; Suess, Lynn A. (1980). TM and cult mania. North Quincy, Mass.: Christopher Pub. House. ISBN 0-8158-0392-3.

- ^ Mason, Paul. The Maharishi. Great Britain. Element Books Limited, 1994. pg 210

- ^ "The Transcendental Meditation (TM) Program - Official website. How and where to learn". TM. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ a b Cotton, Dorothy H. G. (1990). Stress management : an integrated approach to therap. New York: Brunner/Mazel. p. 138. ISBN 0-87630-557-5.

- ^ Washington Parent, Oming in on ADHD, Sarina Grosswald, October 2005

- ^ Harvey, Bob (December 18, 1993). "Establishing Transcendental Meditation's identity; Few can agree if it's a religion, Hinduism or meditation". The Ottawa Citizen. p. C.6.

- ^ "The New Cults", Walter Martin, 1980, p. 95

- ^ "Learn the Transcendental Meditation Technique – Seven Step Program". Tm.org. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ Slee, John, "Towards meditation (with the unmistakable fragrance of money)", The Age (November 4, 1967)

- ^ Souter, Gavin, "Sydney 1967: Non-eternal city", Sydney Morning Herald (December 30, 1967)

- ^ Brothers, Joyce, "Maharishi is vague on happiness recipe", Milwaukee Journal (January 27, 1968)

- ^ LaMore, George "The Secular Selling of a Religion", The Christian Century (December 10, 1975), pp. 1133-1137

- ^ White, John Everything You Want to Know About TM - Including How to Do It Cosimo, Inc., 2004 ISBN 1-931044-85-6, 9781931044851 - Original edition: Pocket Books (1976)

- ^ Kapica, Jack, "Veda Land The New Incarnation of the Maharishi. The Globe and Mail (Toronto, Ont) (Nov 27, 1993) pg. D.3

- ^ Naedele, Walter Jr. "Meditation program goes from 'Om' to 'Ouch'. Philadelphia Inquirer (Aug 30, 1994) pg. B.2

- ^ Independent, Oliver Bennett, Sunday, 31 December 1995

- ^ Overton, Penelope, "Group promotes meditation therapy in schools", Hartford Courant (September 15, 2003) pB1

- ^ Greening, Benedict, "TM courses halted as fees soar", Royal Gazette(Bermuda) (August 16, 2003)

- ^ Stevens, Jacqueline and Barkham, Patrick, "And now children, it's time for your flying lesson", The Guardian (January 27, 2009)

- ^ Johnson, Jenna "Colleges Use Meditation", Washington Post (December 20, 2009)

- ^ Carmiel,Osharat "Wall Street Meditators", Bloomberg (September 18, 2009)

- ^ UK TM

- ^ "Obituary: Maharishi Mahesh Yogi", '"BBC News (February 6, 2008)

- ^ Regush, Nicholas "No bargains on road to enlightenment", Montreal Gazette (July 30, 1977)

- ^ Simon, Alyssa, "David Wants to Fly", Variety (February 14, 2010)

- ^ Knopp, Lisa (1998-11). Flight Dreams: A Life in the Midwestern Landscape. University of Iowa Press. p. 167. ISBN 0877456453.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Scott, R. D. (1978-02). Transcendental misconceptions. Beta Books. pp. 30–31, 36–37. ISBN 0892930314.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Cazenave, Michel (1984-05). Science and consciousness: two views of the universe : edited proceedings of the France-Culture and Radio-France Colloquium, Cordoba, Spain. Pergamon Press. p. 103. ISBN 9780080281278.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Williamson, Lola, Transcendent in America: Hindu-Inspired Meditation Movements as New Religion", NYU Press, 2010 ISBN 0-8147-9450-5, 9780814794500, p. 97

- ^ a b Randi, James (1982). Flim-flam!: psychics, ESP, unicorns, and other delusions. Buffalo, N.Y: Prometheus Books. p. 106. ISBN 0-87975-198-3.

- ^ Ospina p.130

- ^ Ospina p.4

- ^ Ospina p. 148

- ^ Ospina p. 187

- ^ Rainforth MV, Schneider RH, Nidich SI, Gaylord-King C, Salerno JW, Anderson JW (2007). "Stress reduction programs in patients with elevated blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Current Hypertension Reports. 9 (6): 520–8. doi:10.1007/s11906-007-0094-3. PMC 2268875. PMID 18350109.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Orme-Johnson DW (2008). "Commentary on the AHRQ report on research on meditation practices in health". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 14 (10): 1215–21. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.0464. PMID 19123876.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Erin M. Fekete, Michael H. Antoni and Neil Schneiderman, “Psychosocial and behavioral interventions for chronic medical conditions,” Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2007, 20:152–157