1864 United States presidential election: Difference between revisions

Reverted to revision 567445673 by Ariostos: unfortunate but appears to be copyright infringement (unitentional). (TW) |

|||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

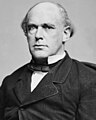

Image:Samuel Portland Chase.jpg|<center>[[United States Secretary of the Treasury|Treasury Secretary]] '''[[Salmon P. Chase]]''' of [[Ohio]]<br><small>(Withdrew on March 5th, 1864)</small></center> |

Image:Samuel Portland Chase.jpg|<center>[[United States Secretary of the Treasury|Treasury Secretary]] '''[[Salmon P. Chase]]''' of [[Ohio]]<br><small>(Withdrew on March 5th, 1864)</small></center> |

||

File:USGrantVignette.jpg|<center>[[Commanding General of the United States Army|Commanding General]] '''[[Ulysses S. Grant]]''' of [[Illinois]]<br><small>(Declined to Contest)</small></center> |

File:USGrantVignette.jpg|<center>[[Commanding General of the United States Army|Commanding General]] '''[[Ulysses S. Grant]]''' of [[Illinois]]<br><small>(Declined to Contest)</small></center> |

||

File: |

File:Vice-President of the United States Hannibal Hamlin.jpg|<center>[[List of Vice Presidents of the United States|Vice President]] '''[[Hannibal Hamlin]]''' of [[Illinois]]<br><small>(Declined to Contest)</small></center> |

||

File:General Benjamin Butler Brady-Handy.jpg|<center>[[Major general (United States)|Major General]] '''[[Benjamin Butler (politician)|Benjamin Butler]]''' of [[Massachusetts]]<br><small>(Declined to Contest)</small></center> |

File:General Benjamin Butler Brady-Handy.jpg|<center>[[Major general (United States)|Major General]] '''[[Benjamin Butler (politician)|Benjamin Butler]]''' of [[Massachusetts]]<br><small>(Declined to Contest)</small></center> |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

| Line 141: | Line 141: | ||

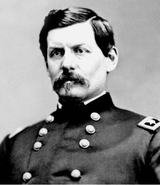

Image:GeorgeMcClellan.png|<center>[[Major General (United States)|Major General]] '''[[George B. McClellan]]''' of [[New Jersey]]</center> |

Image:GeorgeMcClellan.png|<center>[[Major General (United States)|Major General]] '''[[George B. McClellan]]''' of [[New Jersey]]</center> |

||

Image:ThomasSeymour.png|<center>[[List of Governors of Connecticut|Former Governor]] '''[[Thomas H. Seymour]]''' of [[Connecticut]]</center> |

Image:ThomasSeymour.png|<center>[[List of Governors of Connecticut|Former Governor]] '''[[Thomas H. Seymour]]''' of [[Connecticut]]</center> |

||

File:Horatio Seymour - Brady-Handysmall.png|<center>[[List of Governors of New York|Governor]] '''[[Horatio Seymour]]''' of [[New York]]<br>''<small>(Declined to |

File:Horatio Seymour - Brady-Handysmall.png|<center>[[List of Governors of New York|Governor]] '''[[Horatio Seymour]]''' of [[New York]]<br>''<small>(Declined to be Nominated)</small>''</center> |

||

File:Franklin Pierce.jpg|<center>[[President of the United States|Former President]] '''[[Franklin Pierce]]''' of [[New Hampshire]]<br>''<small>(Declined to be Nominated)</small>''</center> |

File:Franklin Pierce.jpg|<center>[[President of the United States|Former President]] '''[[Franklin Pierce]]''' of [[New Hampshire]]<br>''<small>(Declined to be Nominated)</small>''</center> |

||

File:Lazarus W. Powell - Brady-Handy.jpg|<center>[[United States Senator|Senator]] '''[[Lazarus W. Powell]]''' of [[Kentucky]]<br>''<small>(Declined to be Nominated)</small>''</center> |

File:Lazarus W. Powell - Brady-Handy.jpg|<center>[[United States Senator|Senator]] '''[[Lazarus W. Powell]]''' of [[Kentucky]]<br>''<small>(Declined to be Nominated)</small>''</center> |

||

| Line 147: | Line 147: | ||

[[File:Democratic presidential ticket 1864b.jpg|thumb|250px|McClellan and Pendleton campaign poster]] |

[[File:Democratic presidential ticket 1864b.jpg|thumb|250px|McClellan and Pendleton campaign poster]] |

||

<!-- Information of the First Paragraph was grabbed from here: http://elections.harpweek.com/1864/Overview-1864-2.htm --> |

|||

The Democrats were energized by what they saw as the morass of a stagnant Union war effort: death, debt, and destruction with no end in sight. Several of Lincoln’s key policies were also extremely unpopular: emancipation, the military draft, the use of black troops, and violations of civil liberties. Democrats also benefited when the president’s outline of preconditions for peace negotiations, in his “To Whom It May Concern” letter of July 1864, included the stipulation that the Confederate states abolish slavery. Frederick Douglass had had to convince Lincoln not to backpedal, and the president did ultimately stand firm even though it undercut his support among War Democrats and conservative Republicans. Democrats made racial issues a major part of their campaign, insisting that the Republicans were upending traditional race relations and advocating “miscegenation”—a word for racially-mixed marriage allegedly coined during the campaign. |

|||

The Democratic Party was bitterly split between War Democrats and [[Peace Democrats]], who further divided among competing factions. Moderate Peace Democrats who supported the war against the Confederacy, such as [[Horatio Seymour]], were preaching the wisdom of a negotiated peace. After the [[Battle of Gettysburg]], when it was clear the South could no longer win the war, moderate Peace Democrats proposed a negotiated peace that would secure Union victory. They believed this was the best course of action, because an armistice could finish the war without devastating the South.<ref>[[They Also Ran]]</ref> Radical Peace Democrats known as [[Copperhead (politics)|Copperheads]], such as [[Thomas H. Seymour]], declared the war to be a failure and favored an immediate end to hostilities without securing Union victory.<ref>[[The American Pageant]]</ref> |

The Democratic Party was bitterly split between War Democrats and [[Peace Democrats]], who further divided among competing factions. Moderate Peace Democrats who supported the war against the Confederacy, such as [[Horatio Seymour]], were preaching the wisdom of a negotiated peace. After the [[Battle of Gettysburg]], when it was clear the South could no longer win the war, moderate Peace Democrats proposed a negotiated peace that would secure Union victory. They believed this was the best course of action, because an armistice could finish the war without devastating the South.<ref>[[They Also Ran]]</ref> Radical Peace Democrats known as [[Copperhead (politics)|Copperheads]], such as [[Thomas H. Seymour]], declared the war to be a failure and favored an immediate end to hostilities without securing Union victory.<ref>[[The American Pageant]]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 21:00, 6 August 2013

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

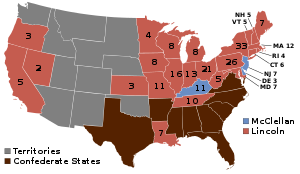

All 233 electoral votes of the Electoral College 117 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential election results map. Red denotes states won by Lincoln/Johnson, blue denotes those won by McClellan/Pendleton, and brown denotes Confederate states. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United States presidential election of 1864 was the 20th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 8, 1864. Abraham Lincoln was re-elected as president. Electoral College votes were counted from 25 states. Since the election of 1860, the Electoral College had expanded with the admission of Kansas, West Virginia, and Nevada as free-soil states, but due to the American Civil War, no electoral votes were counted from any of the eleven Southern states.[1]

Lincoln ran as the Republican nominee against Democratic candidate George B. McClellan, who ran as the "peace candidate" without personally believing in his party's platform. A group of Republican dissidents nominated John C. Frémont, who later withdrew and endorsed Lincoln. In the Border States, War Democrats joined with Republicans as the National Union Party, with Lincoln at the head of the ticket.[2]

On November 8, Lincoln won by more than 400,000 popular votes on the strength of the soldier vote and military successes such as the Battle of Atlanta.[3] Lincoln was the first president to be re-elected since Andrew Jackson in 1832.

Background

The Presidential Election of 1864 took place during the American Civil War. As such, it may be the earliest example of a national election in a democracy during such a war.[4]

Nominations

Radical Democracy Party nomination

Candidate:

-

Former Senator John C. Frémont of California

(Withdrew Sept. 22nd, 1864)

As the Civil War progressed, political opinions within the Republican Party began to diverge. Senators Charles Sumner and Henry Wilson of Massachusetts wanted the Republican Party to advocate constitutional amendments to prohibit slavery and to guarantee racial equality before the law. These bills were not yet supported by all northern Republicans.

Democratic leaders hoped that the radical Republicans would put forth a ticket in the election. The New York World was particularly interested in undermining the National Union Party and ran a series of articles setting forth National Union Convention would be delayed until late in 1864 to allow Frémont time to collect delegates to win the nomination. Frémont supporters in New York City established a newspaper called the New Nation, which declared in one of its initial issues that the National Union Convention would be a "nonentity."

The Radical Democracy Convention assembled in Ohio with delegates arriving on May 29, 1864. The New York Times reported that the hall which the convention organizers had planned to use had been double-booked by an opera troupe. Almost all delegates were instructed to support Frémont, with a major exception being the New York delegation, which was composed of War Democrats who supported Ulysses S. Grant. Various estimates of the number of delegates were reported in the press; the New York Times reported 156 delegates, but the number generally reported elsewhere was 350 delegates. The delegates came from 15 states and the District of Columbia. They adopted the name "Radical Democracy Party."[5]

A supporter of Grant was appointed chairman. The platform was passed with little discussion, and a series of resolutions that bogged down the convention proceedings were voted down decisively. The convention nominated Frémont for president, and he accepted the nomination on June 4, 1864. In his letter, he stated that he would step aside if the National Union Convention would nominate someone other than Lincoln. John Cochrane was nominated for vice-president.[6]

National Union Party nomination

National Union candidate:

-

Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase of Ohio

(Withdrew on March 5th, 1864) -

Commanding General Ulysses S. Grant of Illinois

(Declined to Contest) -

Vice President Hannibal Hamlin of Illinois

(Declined to Contest) -

Major General Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts

(Declined to Contest)

As the incumbent president, Abraham Lincoln faced several obstacles to reelection. Recent history was against him because no sitting president had been reelected in over three decades since Andrew Jackson won a second term in 1832. More importantly, Lincoln faced a continual barrage of criticism aimed at his policies and leadership, particularly against emancipation and his management of the Union military effort. Also, Republicans had lost seats in the 1862 congressional and legislative elections. That was not surprising for a party in power, but in the context of a protracted war of uncertain outcome, some Republican leaders concluded that their party needed a new helmsman if it was to achieve victory in the 1864 elections. Challengers to Lincoln for the presidential nomination would surface as early as 1863.

In an effort to broaden their appeal, Republicans had begun calling themselves the National Union party and invited War Democrats to join them in the new alliance. A few of the Republicans who were unhappy with the president thought that General Benjamin Butler, the Union military commander of New Orleans, could unite War Democrats with the radical and moderate wings of the Republican party. The general lacked sufficient support within the party organization, however, and declined the overtures. A group of radical Republicans tried to persuade Vice President Hannibal Hamlin to throw his hat into the ring, but he stood loyally by Lincoln. The New York Herald urged the nomination of General Ulysses S. Grant, but the Union commander was horrified at such a prospect and was adamant that Lincoln’s election was necessary to the Union cause.

A more genuine threat to the president’s nomination came from his ambitious and talented secretary of the treasury, Salmon P. Chase of Ohio. The dissatisfaction of abolitionists and radicals with Lincoln, especially regarding his hesitancy toward both emancipation and the use of black troops, worsened in December 1863 when the president announced his reconstruction plan, a policy that the radicals judged to be far too mild and cautious. Chase’s commitment to racial equality, on the other hand, was firm and long-standing. The nucleus of his campaign included Whitelaw Reid, the Washington correspondent of the Cincinnati Gazette, Senator John Sherman, Representatives James Garfield and James Ashley, all from the secretary’s home state of Ohio, and Senator Samuel Pomeroy of Kansas, who felt slighted by Lincoln’s distribution of patronage in Kansas. For his part, Chase used Treasury Department patronage to gain support for his candidacy, and he cooperated in the preparation of a campaign biography.

In February 1864, the Chase campaign circulated two pamphlets, both calling for a new president, and the second one explicitly designating Chase as the man for the job. The latter, which became known as “the Pomeroy circular,” had been intended for private dissemination but was leaked to the press. Rather than generate support, its publication created an anti-Chase backlash, prompting even the Republicans of his home state to endorse the president’s reelection. Lincoln himself had essentially ignored Chase’s political activities, but the president’s followers had been working diligently behind the scenes to bolster support for his renomination. Their efforts resulted in numerous state and local Republican organizations climbing aboard the Lincoln bandwagon. Within a few weeks after the fiasco of the Pomeroy circular, Chase announced publicly on March 5 that he was not a candidate for the presidential nomination.

In late June, Chase offered to resign his cabinet post, an empty gesture the secretary had made several times before. This time, however, the president accepted it. When Chief Justice Roger Taney died on October 12, the president knew of Chase’s great desire for the position, but delayed in appointing him. Chase got the message and took to the stump for Lincoln’s reelection. Shortly thereafter, he received the Supreme Court nomination.

The nominating convention of the National Union Party, dominated by Republicans with a scattering of War Democrats, met in Baltimore on June 7-8, 1864. By that time, Lincoln’s supporters had thwarted various insurgencies and secured control of the proceedings. The platform called for pursuit of the war until the Confederacy surrendered unconditionally; a constitutional amendment for the abolition of slavery; aid to disabled Union veterans; continued European neutrality; enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine; encouragement of immigration; and construction of a transcontinental railroad. It also praised the use of black troops and Lincoln’s management of the war. On the first presidential ballot, Lincoln got all of the votes except for 22 cast by Missouri delegates for General Grant. The Missouri faction, however, quickly changed their votes to make Lincoln’s renomination unanimous.

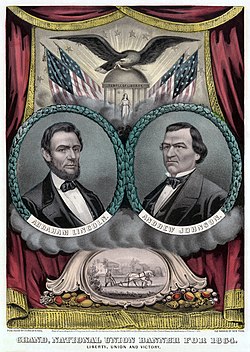

Like many presidents, Lincoln gave little thought to the vice presidency; therefore, he left the selection of his running mate to the convention, expressing no opinion publicly or privately. Vice President Hannibal Hamlin desired to be renominated, but he generated little enthusiasm. Some thought it was important strategically and symbolically to nominate a War Democrat, such as former U.S. Senator Daniel Dickinson of New York. Dickinson’s election, though, would likely put pressure on Secretary of State William Seward, another New Yorker, to resign from the cabinet. The convention swung to Andrew Johnson, the Union military governor of Tennessee, who had the double distinction of being a War Democrat and a Southern Unionist. He was nominated overwhelmingly on the first vice-presidential ballot. Since most radicals were satisfied with the party platform and the direction, though not the pace, of the Lincoln administration on emancipation, Johnson’s nomination was palatable to them.

| Presidential Ballot | Vice Presidential Ballot | ||||

| Ballot | 1st | 1st Revised | Ballot | 1st | 1st Revised |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham Lincoln | 494 | 516 | Andrew Johnson | 200 | 492 |

| Ulysses S. Grant | 22 | 0 | Hannibal Hamlin | 150 | 9 |

| Not Voting | 3 | 3 | Daniel S. Dickinson | 108 | 17 |

| Benjamin Butler | 28 | 0 | |||

| Lovell Rousseau | 21 | 0 | |||

| Schuyler Colfax | 6 | 0 | |||

| Ambrose Burnside | 2 | 0 | |||

| Joseph Holt | 2 | 0 | |||

| Preston King | 1 | 0 | |||

| David Tod | 1 | 1 | |||

-

1st Presidential Ballot -

Revised 1st Presidential Ballot -

1st Vice-Presidential Ballot -

Revised 1st Vice-Presidential Ballot

Democratic Party nomination

Democratic candidates:

-

Governor Horatio Seymour of New York

(Declined to be Nominated) -

Former President Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire

(Declined to be Nominated) -

Senator Lazarus W. Powell of Kentucky

(Declined to be Nominated)

The Democratic Party was bitterly split between War Democrats and Peace Democrats, who further divided among competing factions. Moderate Peace Democrats who supported the war against the Confederacy, such as Horatio Seymour, were preaching the wisdom of a negotiated peace. After the Battle of Gettysburg, when it was clear the South could no longer win the war, moderate Peace Democrats proposed a negotiated peace that would secure Union victory. They believed this was the best course of action, because an armistice could finish the war without devastating the South.[7] Radical Peace Democrats known as Copperheads, such as Thomas H. Seymour, declared the war to be a failure and favored an immediate end to hostilities without securing Union victory.[8]

George B. McClellan vied for the presidential nomination. Additionally, friends of Horatio Seymour insisted on placing his name before the convention, which was held in Chicago, Illinois, on August 29–31, 1864. But on the day before the organization of that body, Horatio Seymour announced positively that he would not be a candidate.

Since the Democrats were divided by issues of war and peace, they sought a strong candidate who could unify the party. The compromise was to nominate pro-war General George B. McClellan for president and anti-war Representative George H. Pendleton for vice-president. McClellan, a War Democrat, was nominated over the Copperhead Thomas H. Seymour. Pendleton, a close associate of the Copperhead Clement Vallandigham, balanced the ticket, since he was known for having strongly opposed the Union war effort.[9] The convention then adopted a peace platform[10] — a platform McClellan personally rejected.[11] McClellan supported the continuation of the war and restoration of the Union, but the party platform, written by Vallandigham, opposed this position.

| Presidential Ballot | Vice Presidential Ballot | ||||||

| 1st | 1st Revised | Unanimous | 1st | 1st Revised | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| George B. McClellan | 174 | 202.5 | 226 | George H. Pendleton | 55.5 | 226 | |

| Thomas H. Seymour | 38 | 23.5 | - | James Guthrie | 65.5 | 0 | |

| Horatio Seymour | 12 | 0 | - | Lazarus W. Powell | 32.5 | 0 | |

| Blank | 1.5 | 0 | - | George W. Cass | 26 | 0 | |

| Charles O'Conor | 0.5 | 0 | - | John D. Caton | 16 | 0 | |

| Daniel W. Voorhees | 13 | 0 | |||||

| Augustus C. Dodge | 9 | 0 | |||||

| John S. Phelps | 8 | 0 | |||||

| Blank | 0.5 | 0 | |||||

-

1st Presidential Ballot -

Revised 1st Presidential Ballot -

1st Vice-Presidential Ballot -

Revised 1st Vice-Presidential Ballot

General election

The 1864 election was the first time since 1812 that a presidential election took place during a war.

For much of 1864, Lincoln himself believed he had little chance of being re-elected. Confederate forces had triumphed at the Battle of Mansfield, the Battle of the Crater, and the Battle of Cold Harbor. In addition, the war was continuing to take a very high toll in terms of casualties. The prospect of a long and bloody war started to make the idea of "peace at all cost" offered by the Copperheads look more desirable. Because of this, McClellan was thought to be a heavy favorite to win the election. Unfortunately for Lincoln, Frémont's campaign got off to a good start.

However, several political and military events made Lincoln's re-election inevitable. In the first place, the Democrats had to confront the severe internal strains within their party at the Democratic National Convention. The political compromises made at the Democratic National Convention were contradictory and made McClellan's campaign inconsistent and difficult.

Secondly, the Democratic National Convention influenced Frémont's campaign. Frémont was appalled at the Democratic platform, which he described as "union with slavery." After three weeks of discussions with Cochrane and his supporters, Frémont withdrew from the race in September 1864. In his statement, Frémont declared that winning the Civil War was too important to divide the Republican vote. Although he still felt that Lincoln was not going far enough, the defeat of McClellan was of the greatest necessity. General Cochrane, who was a War Democrat, agreed and withdrew with Frémont. Frémont also brokered a political deal in which Lincoln removed U.S. Postmaster General Montgomery Blair from office. McClellan's chances of victory faded after Frémont withdrew from the presidential race.

Lastly, with the fall of Atlanta on September 2, there no longer was any question that a Union military victory was inevitable and close at hand.

In the end, the Union Party mobilized the full strength of both the Republicans and the War Democrats under the its slogan "Don't change horses in the middle of a stream." It was energized as Lincoln made emancipation the central issue, and state Republican parties stressed the perfidy of the Copperheads.[12]

Results

Only 25 states participated in the election, since 11 Southern states had declared secession from the Union and formed the Confederacy. Three new states participated for the first time: Kansas, West Virginia, and Nevada. The reconstructed portions of Tennessee and Louisiana chose presidential electors, although Congress did not count their votes.

McClellan won just three states: Kentucky, Delaware, and his home state of New Jersey.

Lincoln was highly popular with soldiers and they in turn recommended him to their folks back home.[13][14] The following states allowed soldiers to cast ballots: California, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Michigan, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin. Out of the 40,247 army votes cast, Lincoln received 30,503 (75.8%), McClellan 9,201 (22.9%), and Scattering 543 (1.3%). Only soldiers from Kentucky gave McClellan a majority of their votes and he carried the army vote in the state by a vote of 2,823 (70.3%) to 1,194 (29.7%).[15]

Of the 1,129 counties making returns, Lincoln won in 728 (64.48%) while McClellan carried 400 (35.43%). One county (0.09%) in Iowa split evenly between Lincoln and McClellan.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a) | Electoral vote(a), (b), (c) |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote(a), (b), (c) | ||||

| Abraham Lincoln | National Union | Illinois | 2,218,388 | 55.0% | 212(b) | Andrew Johnson | Tennessee | 212(b) |

| George Brinton McClellan | Democratic | New Jersey | 1,812,807 | 45.0% | 21 | George Hunt Pendleton | Ohio | 21 |

| Other | 692 | 0.0% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 4,031,887 | 100% | 233(b) | 233(b) | ||||

| Needed to win | 117(b) | 117(b) | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1864 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005. Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

(a) The states in rebellion did not participate in the election of 1864.

(b) The Electors from Tennessee and Louisiana were Rejected. Were they not rejected, there would have been a total of 250 possible electoral votes, and the requirement to win would have been raised to 126.

(c) One Elector from Nevada did not vote

-

Map of presidential election results by county.

-

Cartogram of presidential election results by county.

-

Results explicitly indicating the percentage for the National Union candidate in each county.

-

Cartogram of National Union presidential election results by county.

-

Results explicitly indicating the percentage for the Democratic candidate in each county.

-

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county.

-

Results explicitly indicating the percentage for "other" candidate(s) in each county.

Results by state

| Abraham Lincoln National Union |

George B. McClellan Democratic |

State Total | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | ||||||

| California | 5 | 62,053 | 58.6 | 5 | 43,837 | 41.4 | - | 105,890 | 100 | |||||

| Connecticut | 6 | 44,673 | 51.4 | 6 | 42,285 | 48.6 | - | 86,958 | 100 | |||||

| Delaware | 3 | 8,155 | 48.2 | - | 8,767 | 51.8 | 3 | 16,922 | 100 | |||||

| Illinois | 16 | 189,512 | 54.4 | 16 | 158,724 | 45.6 | - | 348,236 | 100 | |||||

| Indiana | 13 | 149,887 | 53.5 | 13 | 130,230 | 46.5 | - | 280,117 | 100 | |||||

| Iowa | 8 | 83,858 | 63.1 | 8 | 49,089 | 36.9 | - | 132,947 | 100 | |||||

| Kansas | 3 | 17,089 | 79.2 | 3 | 3,836 | 17.8 | - | 20,925 | 100 | |||||

| Kentucky | 11 | 27,787 | 30.2 | - | 64,301 | 69.8 | 11 | 92,088 | 100 | |||||

| Maine | 7 | 67,805 | 59.1 | 7 | 46,992 | 40.9 | - | 114,797 | 100 | |||||

| Maryland | 7 | 40,153 | 55.1 | 7 | 32,739 | 44.9 | - | 72,892 | 100 | |||||

| Massachusetts | 12 | 126,742 | 72.2 | 12 | 48,745 | 27.8 | - | 175,487 | 100 | |||||

| Michigan | 8 | 91,133 | 55.1 | 8 | 74,146 | 44.9 | - | 165,279 | 100 | |||||

| Minnesota | 4 | 25,031 | 59 | 4 | 17,376 | 41 | - | 42,407 | 100 | |||||

| Missouri | 11 | 72,750 | 69.7 | 11 | 31,596 | 30.3 | - | 104,346 | 100 | |||||

| Nevada | 2 | 9,826 | 59.7 | 2 | 6,594 | 40.2 | - | 16,420 | 100 | |||||

| New Hampshire | 5 | 36,596 | 52.6 | 5 | 33,034 | 47.4 | - | 69,630 | 100 | |||||

| New Jersey | 7 | 60,724 | 47.2 | - | 68,020 | 52.8 | 7 | 128,744 | 100 | |||||

| New York | 33 | 368,735 | 50.5 | 33 | 361,986 | 49.5 | - | 730,721 | 100 | |||||

| Ohio | 21 | 265,674 | 56.4 | 21 | 205,609 | 43.6 | - | 471,283 | 100 | |||||

| Oregon | 3 | 9,888 | 53.9 | 3 | 8,457 | 46.1 | - | 18,345 | 100 | |||||

| Pennsylvania | 26 | 296,292 | 51.6 | 26 | 277,443 | 48.4 | - | 573,735 | 100 | |||||

| Rhode Island | 4 | 14,349 | 62.2 | 4 | 8,718 | 37.8 | - | 23,067 | 100 | |||||

| Vermont | 5 | 42,419 | 76.1 | 5 | 13,321 | 23.9 | - | 55,750 | 100 | |||||

| West Virginia | 5 | 23,799 | 68.2 | 5 | 11,078 | 31.8 | - | 34,877 | 100 | |||||

| Wisconsin | 8 | 83,458 | 55.9 | 8 | 65,884 | 44.1 | - | 149,342 | 100 | |||||

| TOTALS: | 233 | 2,218,388 | 55 | 212 | 1,812,807 | 45 | 21 | 4,031,887 | 100 | |||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1864 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005. Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

States with close margins of victory

States in red were won by Republican Abraham Lincoln; states in blue were won by Democrat George B. McClellan.

Below are the states where the margin of victory was under 5%. These closely won states totaled 68 electoral votes:

- New York 0.92% (33 electoral votes)

- Connecticut 2.76% (6 electoral votes)

- Pennsylvania 3.51% (26 electoral votes)

- Delaware 3.62% (3 electoral votes)

See also

- American election campaigns in the 19th century

- Electoral history of Abraham Lincoln

- History of the United States (1849–1865)

- Second inauguration of Abraham Lincoln

- Third Party System

- United States House elections, 1864

Footnotes

- ^ Elections were held in the Union-occupied military districts in the states of Louisiana and Tennessee but no electoral votes were counted from them. Donald, David Herbert, Jean Harvey Baker, & Michael F. Holt, The Civil War and Reconstruction (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2001), 427.

- ^ Martis, Kenneth C., "Atlas of the Political Parties in the United States Congress, 1789-1989" ISBN 0-02-920170-5 p. 117. Altogether they elected 9 Senators and 25 Representatives in Missouri, Kentucky, West Virginia, Maryland and Delaware.

- ^ Davis, William C., "Lincoln's men: how President Lincoln became father to an army and a nation", 1999 ISBN 0-684-83337-9, p. 211. The public entrusted Lincoln with another term in spite of widespread revulsion at the death toll in the Wilderness Campaign. Republicans had found success in gubernatorial races in Ohio and Pennsylvania by attracting the votes of furloughed soldiers. In order to copy the same success nationally, thirteen Union states allowed their citizens serving as soldiers in the field to cast ballots. Four additional Union states allowed "proxy" absentee voting. "By margins of three to one or better, the soldiers [lined up] behind Lincoln." In every state, those returning home influenced their friends and family. For an alternative account of army voting, see W. Dean Burnham, "Presidential Ballots: 1836-1892", pgs. 260-883. Out of the 40,247 Army votes cast in seven states, Lincoln carried six of them with 30,503 votes (75.8%).

- ^ "Abraham Lincoln: The Campaign and Election of 1864". American President: A Reference Resource. University of Virginia. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ "HarpWeek: Explore History, 1864: Lincoln v. McClellan". Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- ^ http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=240652

- ^ They Also Ran

- ^ The American Pageant

- ^ [1]

- ^ 1864 Democratic Platform

- ^ "George B. McClellan". Ohio History Central. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ J. G. Randall and Richard Current, Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure (1955) p. 307

- ^ Phillip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (University Press of Kansas, 1994) pp 274-293

- ^ Oscar O. Winther, "The Soldier Vote in the Election of 1864," New York History (1944) 25: 440-58

- ^ Presidential Ballots: 1836-1892, W. Dean Burnham, pgs. 260-883

Further reading

- Harold M. Dudley. "The Election of 1864," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 18, No. 4 (Mar., 1932), pp. 500–518 full text in JSTOR.

- David E. Long. Jewel of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln's Re-election and the End of Slavery (1994).

- Louis Taylor Merrill, "General Benjamin F. Butler in the Presidential Campaign of 1864." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 33 (March 1947): 537-570. full text in JSTOR.

- Larry E. Nelson, Bullets, Ballots, and Rhetoric: Confederate Policy for the United States Presidential Contest of 1864 University of Alabama Press, 1980.

- Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union: The War for the Union vol 8 (1971).

- Leonard Newman, "Opposition to Lincoln in the Elections of 1864," Science & Society, vol. 8, no. 4 (Fall 1944), pp. 305-327. In JSTOR.

- Phillip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (University Press of Kansas, 1994) pp 274–293.

- James G. Randall and Richard N. Current. Lincoln the President: Last Full Measure. Vol. 4 of Lincoln the President. 1955.

- Michael Vorenberg, "'The Deformed Child': Slavery and the Election of 1864" Civil War History 2001 47(3): 240-257. ISSN 0009-8078 full text in JSTOR.

- Jack Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln: The Battle for the 1864 Presidency (1998).

- Jonathan W. White, "Canvassing the Troops: the Federal Government and the Soldiers' Right to Vote" Civil War History 2004 50(3): 291-317.

- Oscar O. Winther, "The Soldier Vote in the Election of 1864," New York History (1944) 25: 440-458.

External links

- Leip, Dave. "1864 Presidential Election - Home States". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- 1864 popular vote by counties

- 1864 State-by-state popular results

- Transcript of the 1864 Democratic Party Platform

- Harper's Weekly - Overview

- more from Harper's Weekly

- How close was the 1864 election? — Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Abraham Lincoln: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Presidential Election of 1864: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress