User:EnigmaMcmxc/sandbox: Difference between revisions

EnigmaMcmxc (talk | contribs) m →References: changed to 3 columns |

EnigmaMcmxc (talk | contribs) →Overall historical assessment: added new material from main article |

||

| Line 369: | Line 369: | ||

[[File:ManifestaciónContraElTratadoDeVersallesEnBerlín--timeshistoryofwa21londuoft.jpg|thumb|left|alt=A crowd of people, holding plaques, walk towards the camera.|A demonstration in Berlin, in 1919, against the Treaty of Versailles provisions regarding Posen and Danzig.]] |

[[File:ManifestaciónContraElTratadoDeVersallesEnBerlín--timeshistoryofwa21londuoft.jpg|thumb|left|alt=A crowd of people, holding plaques, walk towards the camera.|A demonstration in Berlin, in 1919, against the Treaty of Versailles provisions regarding Posen and Danzig.]] |

||

Albrecht-Carrie comments the peace treaties "were conditioned to a large extent by the previous history of Europe".<ref>Albrecht-Carrie, p. 2</ref> In this light, when reexamining the treaty "the cessions of Belgium, Czechoslovakia and Lithuania were little more than pin pricks" and the "Danish cession was wholly justified."<ref name=A-C12>Albrecht-Carrie, p. 12</ref> In regards to Alsace-Lorraine, he notes that Alsace was "not old French territory" yet "its restoration to France was, almost universally considered to have been warranted" and the French and Germans had almost reconciled on this issue during the inter-war period.<ref>Albrecht-Carrie, p. 3</ref> He concedes that Poland "was looked upon by many as the great territorial crime perpetrated against Germany".<ref name=AC9/> This position is expanded upon by Richard Evans who argues that the German right was committed to an [[Septemberprogramm|annexationist program of Germany annexing most of Europe]] during the war, and found any peace settlement unacceptable that did not leave Germany as the conqueror.<ref name=Evans107/> Albrecht-Carrie argues against the German shock at the loss of territory to Poland. He notes that "the simple fact, which must be duly emphasized, [is] in her career of expansion, Germany had extended her rule over large sections of alien peoples." While "the German people had been a civilizing influence" they "had not known how to win the allegiance of the subject peoples who found in the defeat of the Central Empires their opportunity of liberation."<ref name=A-C12/> Sally Marks notes that the territorial terms of the treaty "did not surprise Germany's cabinet, but shocked the people and generated bitterness." Marks states Gustav Stresemann, who she calls "Weimar's ablest foreign minister", "largely predicted" the losses that the treaty would demand. She highlights that the loss of Alsace-Lorraine and territory to Poland were "anchored in the fourteen points and the armistice" while the "north-Schleswig plebiscite" had been promised in 1866 "by an [[Peace of Prague (1866)|1866 Prussian treaty]]".{{#tag:ref|The 1866 [[Peace of Prague (1866)|Treaty of Prague]] resulted in Austria ceding to Prussia "all the rights acquired over the duchies of Holstein and Schleswig, with the condition that the population of the northern districts of Schleswig should be ceded to Denmark if, by a free vote, they should express a wish to be so united." However, without enacting a plebiscite, the region was annexed by Prussia on 12 January 1867. Around 50,000 people migrated pending this plebiscite. When the vote did not take place, these people returned to their homes in Schleswig "where, owing to their having lost their Danish citizenship and not being allowed by the Prussians - as a punishment - to acquire Prussian citizenship, they became in their unprotected state the special object of persecution in the Prussian efforts to Germanize the country."<ref>Wambaugh, pp. 145-6</ref>|group=nb}} Marks further notes that "the losses - thanks partly to self-determination - were minuscule, amounting to Eupen-Malmedy permanently and the Saar Basin provisionally.<ref name=Martle9919/> Norman Davies highlights that while the Treaty of Versailles "delineated Poland’s frontier with Germany, and the Treaty of Saint-Germain delineated Czechoslovakia’s frontier with Austria" neither of them established the Polish-Czech border leaving a gaping legal hole that "simmered angrily for the next twenty years."<ref>Davies, p. 136</ref> Bernadotte Schmitt comments that the treaty, as well as the Paris Peace Conference as a whole, resulted "for the first time in European history" with "almost every European people ... allowed to obtain independence and a government of its own."<ref name=Schmitt105>Schmitt, p. 105</ref> |

Albrecht-Carrie comments the peace treaties "were conditioned to a large extent by the previous history of Europe".<ref>Albrecht-Carrie, p. 2</ref> In this light, when reexamining the treaty "the cessions of Belgium, Czechoslovakia and Lithuania were little more than pin pricks" and the "Danish cession was wholly justified."<ref name=A-C12>Albrecht-Carrie, p. 12</ref> In regards to Alsace-Lorraine, he notes that Alsace was "not old French territory" yet "its restoration to France was, almost universally considered to have been warranted" and the French and Germans had almost reconciled on this issue during the inter-war period.<ref>Albrecht-Carrie, p. 3</ref> He concedes that Poland "was looked upon by many as the great territorial crime perpetrated against Germany".<ref name=AC9/> This position is expanded upon by Richard Evans who argues that the German right was committed to an [[Septemberprogramm|annexationist program of Germany annexing most of Europe]] during the war, and found any peace settlement unacceptable that did not leave Germany as the conqueror.<ref name=Evans107/> Albrecht-Carrie argues against the German shock at the loss of territory to Poland. He notes that "the simple fact, which must be duly emphasized, [is] in her career of expansion, Germany had extended her rule over large sections of alien peoples." While "the German people had been a civilizing influence" they "had not known how to win the allegiance of the subject peoples who found in the defeat of the Central Empires their opportunity of liberation."<ref name=A-C12/> Sally Marks notes that the territorial terms of the treaty "did not surprise Germany's cabinet, but shocked the people and generated bitterness." Marks states Gustav Stresemann, who she calls "Weimar's ablest foreign minister", "largely predicted" the losses that the treaty would demand. She highlights that the loss of Alsace-Lorraine and territory to Poland were "anchored in the fourteen points and the armistice" while the "north-Schleswig plebiscite" had been promised in 1866 "by an [[Peace of Prague (1866)|1866 Prussian treaty]]".{{#tag:ref|The 1866 [[Peace of Prague (1866)|Treaty of Prague]] resulted in Austria ceding to Prussia "all the rights acquired over the duchies of Holstein and Schleswig, with the condition that the population of the northern districts of Schleswig should be ceded to Denmark if, by a free vote, they should express a wish to be so united." However, without enacting a plebiscite, the region was annexed by Prussia on 12 January 1867. Around 50,000 people migrated pending this plebiscite. When the vote did not take place, these people returned to their homes in Schleswig "where, owing to their having lost their Danish citizenship and not being allowed by the Prussians - as a punishment - to acquire Prussian citizenship, they became in their unprotected state the special object of persecution in the Prussian efforts to Germanize the country."<ref>Wambaugh, pp. 145-6</ref>|group=nb}} Marks further notes that "the losses - thanks partly to self-determination - were minuscule, amounting to Eupen-Malmedy permanently and the Saar Basin provisionally.<ref name=Martle9919/> Ewa Thompson comments how the treaty freed "the Polish nation imprisoned in the German empire" and likewise how "the Treaty of Versailles [also] liberated ... the Czechs, Slovaks, and members of other Eastern European states created as the European empires shrank."<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.owlnet.rice.edu/~ethomp/The%20Surrogate%20Hegemon.pdf|title=The Surrogate Hegemon in Polish Postcolonial Discourse|last1=Thompson|first1=Ewa|page=10|date=22 September 2007|website=Time World|publisher=[[Rice University]]|accessdate=2 October 2013}}</ref> |

||

Norman Davies highlights that while the Treaty of Versailles "delineated Poland’s frontier with Germany, and the Treaty of Saint-Germain delineated Czechoslovakia’s frontier with Austria" neither of them established the Polish-Czech border leaving a gaping legal hole that "simmered angrily for the next twenty years."<ref>Davies, p. 136</ref> Bernadotte Schmitt comments that the treaty, as well as the Paris Peace Conference as a whole, resulted "for the first time in European history" with "almost every European people ... allowed to obtain independence and a government of its own."<ref name=Schmitt105>Schmitt, p. 105</ref> |

|||

[[File:Surviving Herero c1907.jpg|thumb|right|alt=Nine malnourished men and women sit and stand posing for a photograph.|[[Herero people|Hereros]] who had escaped the 1904 - 1907 [[Herero and Namaqua Genocide]] committed by the German Empire. The genocide was an example of how the Allies viewed Germany as incompetent in colonial management.<ref>Totten, pp. 38-9</ref>]] |

[[File:Surviving Herero c1907.jpg|thumb|right|alt=Nine malnourished men and women sit and stand posing for a photograph.|[[Herero people|Hereros]] who had escaped the 1904 - 1907 [[Herero and Namaqua Genocide]] committed by the German Empire. The genocide was an example of how the Allies viewed Germany as incompetent in colonial management.<ref>Totten, pp. 38-9</ref>]] |

||

Revision as of 22:31, 2 October 2013

ToV

| Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Germany[1] | |

|---|---|

Cover of the English version | |

| Signed | 28 June 1919[2] |

| Location | Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles, Paris, France[3] |

| Effective | 10 January 1920[4] |

| Condition | Ratification by Germany and three Principal Allied Powers.[1] |

| Signatories | Central Powers Allied Powers Others |

| Depositary | French Government[5] |

| Languages | French and English[5] |

| Full text | |

The Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Germany, commonly known as the Treaty of Versailles, was one of the peace treaties signed at the Paris Peace Conference following the cessation of the First World War. The treaty ended the state of war between the German Empire and the Allied Powers. While the armistice, signed on 11 November 1918, ended the actual fighting, it took six months of negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference to conclude the peace treaty. The treaty was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in the Hall of Mirrors of the Palace of Versailles, just outside of Paris. The other countries of the Central Powers, the allies of Germany, concluded peace with the victors via separate treaties.[nb 1] The treaty was registered by the Secretariat of the League of Nations on 21 October 1919, and was printed in The League of Nations Treaty Series.

Of the many provisions of the treaty, the main required Germany to disarm, limit her military forces, make territorial concessions, and to pay reparations to various countries. The treaty also called for the creation of the League of Nations. Article 231 was one of the most controversial points of the treaty. It required "Germany [to] accept the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage" during the war. Germans saw this clause as taking full responsibility for the cause of the war, and the article later became known as the 'war guilt clause'. The result, of competing and sometimes conflicting goals among the victors, was a compromise that left none contented. The treaty neither pacified, conciliated, permanently weakened, or reconcile Germany and caused massive resentment. The problems that arose from the treaty, and attempts to stabilize Europe led to the Locarno Treaties, which improved relations between Germany and the other European Powers, and the renegotiation of the reparation payments resulting in the Dawes Plan, the Young Plan, and finally the abolishment of reparations at the Lausanne Conference of 1932.

Contemporary opinion on the treaty varied from too harsh to too lenient. Germans saw the treaty as assigning them responsibility for the entire war and worked hard to undermine this perceived error. Historians, from the 1920s to present, have demonstrated that guilt was not associated with Article 231, and that the clause, which was also included in the treaties signed by Germany's allies mutatis mutandis, was purely a prerequisite to allow a legal basis to be laid out for the reparation payments that were to be made. Critics of the reparations considered them too harsh, counterproductive, damaging to the German economy, and a "Carthaginian peace". However, historical consensus considers the reparations to be largely chimerical (designed to look imposing to mislead the public), which were well within Germany's ability to pay, and that had little direct impact on the German economy. Furthermore, historians have highlighted that Germany received substantial aid, via loans, to make payment and that in the end paid only a fraction of the total sum with the cost of repairs and pensions being shifted to the victors of the war rather than Germany. In assessing the long term impact of the treaty, historians have determined that the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party was not an inevitable consequence of the treaty and likewise neither was the Second World War. Overall, ...

territory - cons: going to Poland, Pros: people were given a say, western territorial losses were nothing really, Germany reconciled over Alsace-Lorraine self determination - cons: couldn't be applied across the board, and Germany was not given the same say. Pros: first time in European history ethnic groups had a say military - cons: no one could agree on anything, no one disarmed, loopholes and German determination to ignore treaty resulted in immediate secret rearming

Historians have judged the treaty to have been lenient and fair, not as harsh as it could have been Overall, critics believed the treaty to have been too harsh, , and deemed the reparation figure to be excessive and counterproductive. However, supporters believed that the treaty had not caused permanent lasting negative effects and that co-operation between nations or the League of Nations would be able to rectify any and all problems.

Historians have demonstrated that a myth was fostered, by German propaganda, during the inter-war years that treaty was unduly harsh and that this myth is still commonly held today by the public and remains the key lesson taught in school textbooks. Finally, historians have noted when the treaty is placed in context and compared with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which Germany imposed upon Soviet Russia in early 1918, that the Versailles treaty was extremely lenient.

Background

In 1914, the First World War broke out. For the next four years fighting waged across Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia resulting in most of the world being dragged into the war.[6] In 1917, the Russian Empire was rocked by two revolutions that brought about the collapse of the Imperial government and the rise of the Bolsheviks led by Vladimir Lenin.[7]

On 8 January 1918, the President of the United States Woodrow Wilson issued a statement known as the Fourteen Points.[8] The statement called for a diplomatic end to the war, international disarmament, the withdrawal of Central Power forces from the lands they had occupied up until this point, the creation of a Polish state, the redrawing of borders in Europe along ethnic lines, and the formation of a League of Nations to afford "mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike".[9] For his efforts Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize,[10] and his speech ultimately resulted in the Germans attempting to broker a peace based on these points.[11]

After further fighting on the Eastern Front, the new Soviet government of Russia signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the German Empire on 3 March 1918. This treaty forced Russia to yield sovereignty of Russian-Poland and the Baltic States to Germany, recognize the independence of the Ukraine, pay six billion Marks (ℳ) in reparations among many other stipulations.[12] The German "imposition of harsh terms on Russia ... just two months after the announcement of the Fourteen Points seemed ... to demonstrate that German had no right to demand or expect leniency."[13]

In the autumn of 1918, the Austrian-Hungarian Empire collapsed, and the various ethnic groups of the empire rose up to establish their own successor states and gain full independence.[14] In Germany, the rate of desertion within the military increased[15] as did civilian strikes.[16] On the Western Front, the Allied forces had launched the Hundred Days Offensive that decisively defeated the German military.[17] During this period, the German navy, unwilling to be sent on a suicidal climatic battle, mutinied resulting in further uprisings across Germany.[18] This coupled with rising civilian social tension and defeat of the military, resulted in the German Revolution[19] and the German government attempting to broker a peace based on Wilson's Fourteen Points.[20] The war ended on 11 November, with German forces still in France and Belgium and before allied forces had entered German territory.[21]

In late 1918, a Polish government was formed and an independent Poland proclaimed. In December, Poles launched an uprising within the German province of Posen. Fighting lasted until February when an armistice was signed leaving the area in Polish hands, but technically still German.[22] In late 1918, Allied troops entered Germany and initiated the occupation of the Rhineland.[23] The defeat of the Central Powers resulted in the Paris Peace Conference. The conference aimed to establish peace between the war's belligerents and establish the post-war world. The Treaty of Versailles formed part of the conference, and dealt solely with Germany.[24] The treaty, along with the others that were signed during the Paris Peace Conference, were each named after the suburb of Paris they were signed in.[25]

Negotiations

Historian Jim Powell comments that the British "favored a neutral site like Geneva, Switzerland" for the peace negotiations to take place at, however the French wanted to hold the conference in Paris, a position the Americans supported.[26]

Negotiations between the Allied powers started on 18 January 1919, in the Salle de l'Horloge at the French Foreign Ministry, on the Quai d'Orsay in Paris.[27] Initially, 70 delegates of 26 nations participated in the negotiations.[28] Representatives from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic were not invited, due to their early withdrawal from the war.[29] Bernadotte Schmitt highlights that "the tradition of peace conferences was that belligerents met on terms of equality", however as the Allies were at odds with each other they did not invite Germany thus avoiding Germany attempting to play one country off against the other and unfairly influencing the proceedings.[25] Norman Davies declares a German delegation was only invited to "sign the Treaty ... without comment"[30] although as historian P.M.H. Bell points out "the whole object of winning the war was to impose upon Germany terms which she would never accept voluntarily".[31]

It rapidly became evident that the major powers would make most of the decisions. After some debate, it was decided that a 'Council of Ten', comprising the heads of government and foreign ministers of the five major victors (the United Kingdom, France, the United States, Italy, and the Empire of Japan), would meet in private sessions to negotiate the terms of the peace. The minor powers would attend "a weekly Plenary Conference, during which treaty-related issues would be discussed in a general forum". These members "were also given the opportunity to form commissions that were entrusted with studying and making recommendations regarding various aspects of the peace settlement". Over fifty committees and commissions were founded "whose findings on a host of issues formed the basis for most of the provisions that found their way into the treaties".[32][33] The 'Council of Ten' "proved too cumbersome for any real progress" and in late March was replaced. The foreign ministers "continued to meet in a separate body", known as the 'Council of Five', to discuss "less important matters" while the heads of state from America, Britain, France, and Italy, dubbed the 'Council of Four', met in informal meetings to debate the major issues.[33] Temporarily, the 'Council of Four' became the 'Big Three' when the Italian prime minister left the conference.[34]

Overall Allied aims

Georges Clemenceau, the French Prime Minister, is quoted as saying "if only we could get rid of Germany, there would be peace in Europe."[35] However, historian Gerhard Weinberg comments that regardless "of even the harshest terms proposed ... the continued existence of a German state, however truncated or restricted, was taken for granted by all" despite how Germany was formed or their long-term plans for Belgium.[36] Wilson commented "We do not wish to destroy German and we could not do so if we wished." The British position on the future of Germany was that it should remain to be "a political counterweight to France and to resume her prewar role as Britain’s chief trading partner."[35]

Weinberg further notes that Germany was viewed, as a result of the long and bitter war and the number of nations needed to defeat her, as "extraordinarily dangerous to the welfare, even existence, of other" European nations.[21] As a result, the victors sought to break 'Prussian militarism' by dissolving the German General Staff, which was "the brain and nerve center of the army". With Germany disarmed and her general staff dissolved, this would "render possible the initiation of a general limitation of the armaments of all nations".[37] To further this goal and due to an universal conviction among the victors "that Germany had misgoverned its colonies", it was believed "it would be dangerous to restore the colonies because Germany might try to raise troops in the colonies to offset the reduction imposed upon it"[38] Due to Germany’s invasion of Belgium, and her conduct in that country, coupled with the devastation brought upon French soil brought about the want to "limit German power in the future" so other nations could survive.[36]

Professor Ian Beckett sums up the goals of the three main powers: The French wanted "a punitive settlement", the British were after international stability, and the Americans desired "to create a better world based on principles of internationalism, democracy and self-determination."[39] Overall, it was "hoped that a just and lasting peace would be concluded, that the war which [was] won would be the last war."[38]

French aims

No other country "had suffered more at the hands of the Reich ... than France". France suffered 1.3 million soldiers killed – "fully one out of four French men ages 18-30" – along with 400,000 civilians. France "lost a significantly higher percentage of its prewar population than any other nation in the conflict, including Russia." In addition, the country had "also sustained considerable more physical damage than any other nation".[40] German troops had devastated France, including "France’s most industrialized region and the source of most of its coal and iron ore, the Northeast." "Adding insult to injury, during the final days of the war" mines had been flooded, and railroads, bridges, and factories destroyed. Twice, within the space of fifty years, Germany had invaded France.[41] Therefore, Georges Clemenceau's primary objective "was above all to ensure the future security of France against Germany, which he was sure would be intent on revenge".[42] Additional goals included weakening Germany economically, militarily, territorially[41] and to make France "Europe’s leading steel producer".[43] Clemenceau described France's position best by telling Wilson: "America is far away, protected by the ocean. Not even Napoleon himself could touch England. You are both sheltered; we are not".[44]

Originating with a proposal from Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the French wanted "a strategic frontier on the Rhine". Only a frontier on the Rhine "could protect France from a repetition of 1870 and 1914" and offset the various weaknesses of France when compared to Germany.[45] This position was adamantly rejected by the American and British representatives, and it took two months of negotiations for the French to back down and accept an alternative. The British pledged that they would provide an "immediate alliance" with France if Germany attacked again, and Woodrow Wilson "agreed to put to the United States Senate a similar proposal". As Clemenceau held personal doubts if the annexation of the Rhineland would actually benefit France and recognized that France had survived due to an alliance, he could not afford to alienate himself from his allies. He had proclaimed to the Chamber of Deputies in December 1918, that his primarily goal was to maintain an alliance with both countries. Consequently, Clemenceau agreed to the offer, under the provision that the Rhineland would be occupied by France for 15 years (negotiated down by the Anglo-Americans from 30 years), and that Germany would accept the Rhineland as a demilitarized zone.[46] In the long run the American Senate never ratified these decisions,[47] and historian Anthony Lentin argues that when the terms were put to the Germans, they "were maximum demands which might be reduced, but could not be augmented".[48]

In addition, France wanted to impose "heavy reparations on Germany" for two reasons: to make Germany pay for the damage caused during the war, and to weaken Germany for the considerable future.[41] To further weaken Germany and to "compensate for the hundreds of French mines and factories destroyed during the war", France wanted the "iron ore and coal-rich Saar Valley" to be annexed to France.[49] France, along with the British Dominions and Belgium, "were thoroughly opposed" to the concept of mandates and favored outright annexation of Germany’s ex-colonies.[38] Economist John Maynard Keynes argued that "the policy of France" was "to set the clock back and undo what ... progress ... Germany had accomplished."[50] Lentin counters this point by noting that Clemenceau "was too much a realist to argue for" such a position, yet he "sought 'physical guarantees' to prevent yet another invasion".[35] Keynes continued his argument stating by arguing for the annexation of territory, France would be able to curtail the German population and economy. "If France could seize, even in part, what Germany was compelled to drop, the inequality of strength between the two rivals for European hegemony might be remedied for generations."[50]

British aims

William Bullitt, an American delegate at the Paris Peace Conference and who later resigned his position in protest of Wilson, stated that the British went to the conference with a number of secret aims that were not admitted publically. They were "the destruction of the German Navy, the confiscation of the German merchant marine, the elimination of Germany as an economic rival, the extraction of all possible indemnities from Germany, the annexation of German East Africa ... the Cameroons, [and] the annexation of all German colonies in the Pacific south of the Equator." Bullitt concluded, post-treaty, that "all of these secret war aims ... were achieved in one form or another by the Treaty of Versailles."[51]

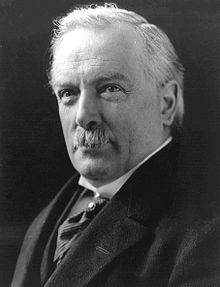

Prime Minister David Lloyd George was a Coalition Liberal who was reelected at the end of 1918.[52] One of the party slogans, during the election, was "squeeze the German lemon 'til the pips squeak"[53] and the general public were not in favor of a "soft peace" as reflected in the British press at the time. The general public opinion was that there should be a "just peace", but one that "would leave Germany powerless to repeat the aggression of 1914 and a peace which would compel it to pay for the damage" although those of a "liberal and advanced opinion" instead shared Wilson’s ideals of a peace of reconciliation.[20]

In private, however, Lloyd George opposed the hawkish mentality of the public[53] and attempted to steer "a middle course between Clemenceau’s demands and Wilson’s Fourteen Points" as he "recognized that at some time in the future, Europe would have to reconcile with Germany."[54] While he supported imposing reparations on Germany, he did not want to do so under terms that would cripple the German economy as this would have a knock on effect across Europe. Furthermore, he wanted Germany to recover so they would remain a viable economic power, and a major trading partner.[53][54] In arguing that Britain’s war pensions and widows allowances should be included in the German reparation sum, this "ensured that a substantial share would go to the British Empire".[55]

The future security of Britain and the European balance of power were also key points Lloyd George attempted to address.[53] As Britain and France were old rivals, "Lloyd George intended to thwart France’s attempt to establish itself as the dominant European Power."[54] A non-crippled Germany would be able to act as a buffer to the French and a deterrent to "Bolshevik Russia", thus maintaining the balance of power "in which no single nation ... [would be] able to dominate". This policy, it was believed, was in the best interests of British national security and European peace.[53] Furthermore, Lloyd George wanted to neutralize the German navy so that he Royal Navy "would once again be the greatest naval power in the world."[54]

The German colonial empire was to be dissolved, "preferably ceding some of its territorial possessions to Britain",[54] yet Lloyd George was an sincere advocate "of the principle of mandates" and wanted to place the German colonies "under the jurisdiction of the League of Nations." However, this position was strongly opposed by the Dominions of Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.[38]

American aims

Jim Powell calls Wilson, the "weakest of the major players at Versailles". He notes that Edward M. House and the United States Secretary of State Robert Lansing both advised Wilson, who was not a skilled negotiator, not to attend and instead send a representative "who had not been authorized to depart form the Fourteen Points" thereby the Americans could "maintain a strong negotiating position". Instead, Wilson "insisted on going ... because it was his dream ... to play on a world stage".[26] Walter McDougall furthers this point, arguing that "Wilson ventured into matters far beyond his understanding".[56] In November 1918, the Republican Party won the Senate election by a slim margin. Wilson, a Democrat, refused to take any Republican senators with him thus encountered opposition "when the treaty came before the Senate".[26] Schmitt notes that Wilson was essentially powerless and "the Republican opposition ... [gave] Wilson’s opponents at Paris [the understanding] ... that he did not have the support of the American people."[25]

Schmitt argues that the American position was in "favor of a moderate peace, a peace of reconciliation, or as [Wilson] called it, 'a peace without victory,' by which he meant a peace without the punishment which victory sometimes induces governments to inflict."[20] Powell takes a more cynical point of view. He comments that Wilson posed "as a generous peacemaker while letting Clemenceau do the dirty work for revenge they both wanted."[57] Lentin goes further. He notes "by March 1919" Wilson had concluded "Germany deserved a hard, deterrent peace in view of her 'very great offence against civilization' and that the League of Nations would iron out injustices."[58] Daniel Smith observes that "the Fourteen Points were 'a bold psychological move' that boosted American and Allied morale and weakened to some degree the will and temper of the Central Powers. However, though 'sufficiently vague and idealistic for war propaganda purposes,' ... Versailles would prove them 'inadequate for peacemaking'"[59]

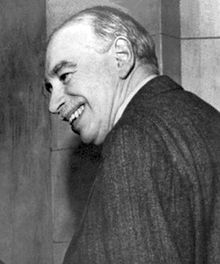

The first priority, and "most important goal" of Wilson, "was the establishment of an international peacekeeping organization, or League of Nations." It was believed that such a body would "bring an end to all war", provide a forum to discuss adjustments or hammer out any flaws within the various treaties of the Paris Peace Conference, and deal with any future problems arising in Europe due to the end of the war and the rise of new states.[60][54] Keynes comments "It was commonly believed ... that the President had thought out ... a comprehensive scheme not only for the League of Nations, but for the embodiment of the Fourteen Points in an actual Treaty of Peace. But in fact the President had thought out nothing; when it came to practice his ideas were nebulous and incomplete. He had no plan, no scheme, no constructive ideas whatever ... ."[61]

In regards to the German colonial empire, Alan Sharp notes that the victors "simply wanted to annex the territories their troops had wrestled from the enemy" yet "to Wilson ... outright annexation constituted a clear violation of the fundamental principles of justice and human rights that he believed must underpin any truly equitable and lasting peace settlement." Wilson favored the native people having "the right of self-determination" and the major powers – under League of Nation oversight – would take control of these regions via mandates. The major powers "would act as a disinterested trustee over the region, promoting the welfare of its inhabitants in a variety of ways" until they were able to govern themselves. Sharp notes that "the mandate plan had prejudicial overtones in its assumption that the colonies' indigenous populations could not be entrusted with self-rule without first being tutored".[62] In spite of this position, to ensure that Japan did not refuse to join the League of Nations, Wilson was in favor of turning over Shandong to Japan rather than return the area to China.[63]

Treaty content

Schmitt notes that "the treaties were drafted by hundreds of persons. Each man did his own little job and then the pieces were glued together by a few big shots, who did not fully sense the enormity of the demands".[64] Lentin comments that the "whole package of terms was approved unamended by the Big Three without adequate co-ordination or review ... . No one had read them in full let alone discussed their cumulative effect." Lloyd George "admitted that he only received a complete copy at the last moment" and Wilson commented "I hope that during the rest of my I will have enough time to read this whole volume".[34]

The allies declared that if the German government did not sign the treaty, the war would be resumed. This caused the collapse of the German government who were unwilling to sign the treaty, and the establishment of a new one. Gustav Bauer, the new German chancellor, sent a telegram stating his intention to sign the treaty if certain articles were withdrawn from the treaty, including articles 227, 230, and 231.[nb 2] The allied response was "the time for discussion is past" and announced that Germany either accept the treaty as it stood or allied forces would cross the Rhine within 24-hours. On 23 June, Bauer sent a second telegram to inform Clemenceau that a German delegation would arrive shortly to sign the treaty.[65]

On 28 June 1919, the fifth anniversary of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which provided the immediate spark for war, the peace treaty was signed.[2] The treaty dealt with numerous issues ranging from war crimes,[66] the prohibition on the merging of Austria with Germany unless with the consent of the League of Nations,[67] the freedom of navigation on major European rivers,[68] to the returning of a Koran to the king of Hedjaz.[69] The major points are discussed below.

Treaty requirements

Territorial changes

By the time the First World War broke out, Germany - as a single state - had only been in existence for 43 years following its official establishment in 1871.[70] The treaty stripped Germany of 25,000 square miles of territory and 7 million people. It also required Germany to give up the gains made via the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and grant true independence to the protectorate states that had been established.[71]

In Western Europe, Germany was required to recognize Belgian sovereignty over the "contested territory [of] Moresnet", and cede control of the Eupen-Malmedy area. Within six months of the transfer, Belgium was required conduct a plebiscite on whether the citizens of the region wanted to remain under Belgian sovereignty or return to German control, communicate the results to the League of Nations and abide by the League’s decision.[72] "As compensation for the destruction of" French coal-mines, Germany was to cede the output of the Saar coalmines to France and control of the region to the League of Nations for fifteen years. At the end of that period, a plebiscite would be held to establish "the sovereignty under which" the citizens of the territory "desire[d] to be placed".[73] "Recognizing the moral obligation to redress the wrong done by Germany in 1871", the treaty "restored" the territory of Alsace-Lorraine to France reverting the outcome of 1871 Treaty of Versailles and the Treaty of Frankfurt.[74] The issue of Schleswig-Holstein was to resolved via referendum to held at a future date.[75]

In Eastern Europe, Germany was to recognize the "complete independence of the Czecho-Slovak State" and to cede over portions of the province of Upper Silesia.[76] Likewise, Germany had to recognize the independence of Poland and renounce "all rights and title over the territory". Portions of Upper Silesia were to be ceded to Poland, with the future to be decided via plebiscite.[77] The province of Posen (now Poznan), which had come under Polish control during the Greater Poland Uprising,[22] was also to be ceded to Poland.[78] The area of Pomerania, based on historical and ethnic grounds, was transferred to Poland so that the new state could have access to the sea. This area would become known as the Polish Corridor.[79] The sovereignty of southern section of East Prussia was to be decided via plebiscite[80] while the East Prussian Soldau area – due to it laying astride the rail line between Warsaw and Danzig – was transferred to Poland outright without any plebiscite being required.[81] In total, 51,800 km2 (20,000 sq mi) of territory was granted to Poland at the expense of Germany.[82] Memel was to be ceded to the Allied and Associated powers, for them to decide the territory’s future fate.[83] Germany was to cede the city of Danzig and its surrounding area, including the delta of the Vistula River on the Baltic Sea, to the League of Nations to establish the Free City of Danzig.[84]

Article 119 of the treaty required "Germany [to] renounce all rights, titles and privileges" over her former colonies while article 22 required that these territories would be turned into mandates entrusted to member nations to tutor and develop the regions.[85] The former German African colonies of Togoland and German Kamerun (Cameroon) were transferred to France as mandates.[86] Ruanda and Urundi, were allocated to Belgium as mandates,[87] while German South-West Africa went to South Africa as a mandate, and the United Kingdom obtained German East Africa as a mandate.[88] As compensation for the German invasion of Portugal’s African empire, Portugal was granted the Kionga Triangle, a sliver of German East Africa in northern Mozambique.[89] Article 156 of the treaty transferred German concessions in Shandong, China, to Japan rather than returning sovereign authority to China.[90] Furthermore, Japan was granted all German possessions in the Pacific north of the equator as mandates, while those south were granted as mandates to Australia although New Zealand took German Samoa as a mandate.[87]

Military restrictions

The treaty was "both comprehensive and complex" in regards to the restrictions placed upon the German military. The treaty was "formulated to restrict the German army so that Germany would not be capable of conducting any offensive actions"[91] and "in order to render possible the initiation of a general limitation of the armaments of all nations".[92]

The treaty required Germany to demobilize, and reduce her armed forces so that by 31 March 1920, and thereafter, the army would compose no more than 100,000 men (including officers and administration personnel) within a maximum of seven infantry and three cavalry divisions. The treaty also laid out how these divisions and support units were to be organized. The general staff was to be dissolved and not reformed.[93] The number of military schools, used to train officers, was to be limited to three: "one school per arm". Conscription was to be abolished. Enlisted men and Non-commissioned officers were to be retained for at least 12 years, and officers for at least 25 years with officers who had left the service being forbidden to attend military exercises. To prevent Germany from building up a large cadre of trained men, the number of men allowed to leave before the completion of their service was to be regulated.[94] Civilian staff supporting the army were to be downsized and the police force reduced to its pre-war size to "only be increased to an extent corresponding to the increase of [the] population". Furthermore, paramilitary forces were forbidden.[95]

The fleet was allowed to retain six pre-dreadnought battleships, but was not allowed to exceed this figure. The fleet could not exceed six light cruisers (not exceeding 6,000 long tons (6,100 t)), twelve destroyers (not exceeding 800 long tons (810 t)) and twelve torpedo boats (not exceeding 200 long tons (200 t)) and was forbidden from having submarines.[96] The manpower of the navy was not to exceed 15,000 men. This figure included "the manning of the fleet, coast defenses, signal stations, administration and other land services ... including officers and men of all grades and corps". In addition the officer and warrant officer strength was not allowed to exceed 1,500 men.[97] In addition, Germany had to surrender eight battleships, eight light cruisers, forty-two destroyers, and fifty torpedo boats - not already in Allied hands - so that they could be decommissioned. Likewise, thirty-two auxiliary ships were to be disarmed and converted to merchant use.[98]

Germany was to disarm and dismantle all fortifications west of the Rhine, and 50 km (31 mi) east of the river. Future construction was forbidden. The Rhineland was to be a demilitarized zone with the German army forbidden to enter.[99] Likewise, all military related structures and fortifications on the islands of Heligoland and Düne were to be destroyed.[100] Germany was prohibited from the importing or exporting of weapons, restricted on what weapons and the number the German army could stockpile and use, prohibited from the manufacture or stockpile of chemical weapons, armored cars, tanks, and military aircraft.[101]

Reparations

Article 231 stated Germany accepted responsibility for "all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies."[102][nb 3] The following articles note that Germany will compensate the Allied powers "for all the damage done to the civilian population ... and to their property during the" war. It goes on to state that a 'Reparation Commission' will "consider the resources and capacity of Germany", give the "German Government a just opportunity to be heard", and decide on the overall level of reparations Germany will pay.[107]

Guarantees

To ensure that Germany abided by the treaty, the Rhineland "together with the bridgeheads" east of the River Rhine, were to be occupied by Allied troops "for a period of fifteen years".[108] If by that point Germany had not initiated any acts of unprovoked aggression, then a staged withdrawal would take place. First, after five years, "the bridgehead at Cologne and the territories north of a line running along the Ruhr" would be evacuated. After ten years, the bridgehead at Coblenz and all territories to the north would be evacuated. Finally, after fifteen years, all remaining forces would be withdrawn. However, if Germany was to act belligerent the occupation forces would remain for as long as needed.[109] If, following the withdrawal of forces, Germany rescinded on the obligations imposed upon her by the treaty, then the above areas would "be reoccupied immediately".[110]

The creation of international organizations

Part I of the treaty was the Covenant of the League of Nations, which provided for the creation of the League of Nations, an organization intended to arbitrate international disputes and thereby avoid future wars.[111] Furthermore, Part XIII organized the establishment of the International Labour Officer, to promote "the regulation of the hours of work, including the establishment of a maximum working day and week; the regulation of the labour supply; the prevention of unemployment; the provision of an adequate living wage; the protection of the worker against sickness, disease and injury arising out of his employment; the protection of children, young persons and women; provision for old age and injury; protection of the interests of workers when employed in countries other than their own; recognition of the principle of freedom of association; the organization of vocational and technical education and other measures".[112]

Reaction to the treaty

Among the allies

The signing of the treaty was met with roars from approval, singing and dancing from a crowd waiting outside the Palace of Versailles. Paris was the scene of celebration as people rejoiced the official end of the war.[113] However, Georges Clemenceau "endured bitter attacks by the French Right" once the treaty was signed.[114] He even conceded that he too was dissatisfied with the overall treaty. Historian Norrin Ripsman claims that Clemenceau’s compromises over the Rhine resulted in his defeat during the January 1920 presidential elections,[115] however, Spencer C. Tucker notes that the political situation in France was much more complicated than that and "most observers" had "expected" Clemenceau to win.[114] As a result of France not being able to annex the Rhineland and for "what he regarded as ... Clemenceau’s trading away French security in order to please the United States and Britain", Marshal Foch declared "This is not peace. It is an armistice for twenty years."[116] Overall, French politicians criticized the treaty for "being too lenient"[117] although Left-wing politicians resented it for just the opposite. "As late as August 1939" some "still began their remarks on foreign affairs with a ritual condemnation of the Treaty".[118]

Harold Nicolson, a diplomat among the British delegation, wrote in his diary "are we making a good peace?" and remained unconvinced by the treaty.[58] General Jan Smuts, a member of the South African delegation at the peace conference, wrote to Lloyd-George (prior to the signing of the treaty) to state he believed the treaty to be unstable[119] and declared "Are we in our sober senses or suffering from shellshock? What has become of Wilson’s 14 points?" He would go on to plead "For the sake of the future", the Germans "should not be made to sign at the point of the bayonet" and called for radical changes to the treaty. When Smuts finally signed the treaty, he issued a statement condemning the treaty and regretting that the promises of "a new international order and a fairer, better world are not written in this treaty". Lord Robert Cecil also declared that many within the Foreign Office were disappointed by the treaty.[58] However, Lloyd George and his private secretary Philip Kerr, a politician who had "been involved in top level decision making in the United Kingdom for several years"[120] both believed in the treaty although they also felt that "France was going to keep Europe in constant turmoil over the enforcement" of the treaty.[121]

The treaty was "received with widespread approval" in the United Kingdom, and the "average Englishman ... thought Germany got only what it deserved".[117] As German complaints mounted "it soon came to be thought" that the treaty was "not morally binding".[118] Schmitt notes it was "only much later that the idea grew up that the five treaties of Paris had been conceived in iniquity and deserved to be revised or forgotten"[117] while Louise Slavicek states that John Maynard Keynes best-selling The Economic Consequences of Peace – "accurate or not" – did much to sway public opinion against the treaty.[122] Writing in 1919, Keynes argued that the reparation figures were too high in relation to the actual damage done, that Germany would not have the capacity to pay, and that if the figures were not revised it would place "an impossible strain on the German economy" and would render impossible, the reconstruction of the European economy.[123] The perception that a Carthaginian peace had been handed out to Germany "engendered ... a sense of guilt that sapped the will" of the British "to uphold a treaty felt to be unjust."[124]

Edward House recorded in his diary "I am leaving Paris, after eight fateful months ... Looking at the conference in retrospect there is much to approve and much to regret. It is easy to say what should have been done, but more difficult to have found a way for doing it." He continues "To those who were saying that the Treaty is bad and should never have been made and that it will involve Europe in infinite difficulties in its enforcement, I feel like admitting it. But I would also say in reply that empires cannot be shattered and new states raised upon their ruins without disturbance. To create new boundaries is always to create new troubles ... While I should have preferred a difference peace, I doubt whether it could have been made, for the ingredients for such a peace as I would have had were lacking at Paris." He concludes his thoughts "And yet I wish we had taken the other road, even if it were less smooth, both now and afterward, than the one we took. We would at least have gone in the right direction and if those who follow us had made it impossible to go the full length of the journey planned, the responsibility would have rested with them and not with us."[125]

In the United States, as seen via the press at the time, there was general approved of the treaty.[117] In September 1919, while speaking on the League of Nations to a luncheon audience in Portland, Woodrow Wilson concluded his speech stating people could now say "at last the world knows America as the savior of the world!"[126] However, Wilson’s perceived pro-British attitude and "failure to speak out" about Ireland "alienated" Irish-American support for Wilson and the League of Nations. "Other ethnic groups, especially the Italians and the Germans, annoyed with Wilson for other reasons, lent editorial support to" the Irish.[127] Furthermore, "many Americans were disillusioned with the sacrifices of World War I and were determined not to repeat what they saw as a mistake" and the public took on an isolationist tone during the 1920s. "Reflecting the conservative internationalist perspective" Henry Cabot Lodge attacked the treaty and proposed amendments "designed to defeat the purpose of U.S. membership in the League." Lodge wanted to be able to trade with Europe, but not be entangled in "alliances or political commitments that would involve the United States in the inevitable next 'European war'".[128] Most of the Democratic senators supported the ratification of the treaty, however there was strong opposition from the Republican Party. The Republicans were divided into groups on the issue, the most strongly opposed were known as the irreconcilables. The irreconcilables opposition ranged from anti-imperialist views such as the "treaty [w]as an imperialist document that strengthened British power", general Anglophobia, concerns that the International Labor Organization would create a "socialistic supergovernment", to racist opposition on the grounds that the inclusion of nations such as Haiti and Liberia would create "a colored league of nations".[129] Opposition to Article X of the Covenant of the League of Nations was a primary theme for the Republican party. As Wilson was unwilling to compromise with his critics or his supporters, who urged for concessions, support collapsed resulting in the Senate refusing to ratify the treaty or America’s role in the League of Nations.[130] Bell comments that "having done so much to win the war and shape the peace treaties that followed" America withdrew back across the Atlantic "not into 'isolation' ... but into an indifference towards the European balance of power which came only too naturally to a people who found the phrase itself distasteful."[131]

The Chinese "were so incensed" by the allocation of Shantung to Japan, that they refused to sign the treaty.[63] Chen Duxiu, who later became the first leader of the Chinese Communist Party, saw the treaty as a "national humiliation" for China.[132] Bruce Elleman argues that the treatment of China resulted in closer Sino-Soviet relations and the communist party becoming more popular in China than western democracy.[133]

On the whole, there was a prevailing sense of criticism towards the treaty among the population of the victors. The treaty was "criticized at the time and for the next twenty years for its harshness, its economic errors, and its inherent instability".[7] Yet, at the same time, the "widely perceived" problems of the treaty were "thought to be not beyond remedy". There was faith in the League of Nations, and it was hoped that it or a revival "of something like the nineteenth-century 'Concert of Europe', an informal grouping of the great powers" could solve Europe’s problems.[134]

In Germany

Across Germany, the treaty was met with widespread outcry.[117] Flags were lowered to Half-mast and demonstrations took place.[135] Germans claimed that their country had been treated unfairly by the treaty, believed that the victors of the war were acting in spite against them, that the treaty was too harsh and contradicted the Fourteen Points – on the basis of which Germany had surrendered, and disagreed with the methods of how the treaty had been formulated. The treaty was seen as a dictated peace, and was later referred to as the Diktat.[136][137] Revision of the treaty "became a major objective of every German political party".[138]

On 7 May, prior to the signing of the treaty, Count Brockdorff-Rantzau – "with the big treaty still lying unopened before him" – declared "The demand is made that we shall acknowledge that we alone are guilty of having caused the war. Such a confession in my mouth would be a lie".[139] This position deepened once the treaty had been signed. Article 231, the so called ‘war guilt’ clause, "aroused deep resentment in Germany, where it was thought that equal (or greater) responsibility for the outbreak of the war could be found in the actions of other countries". German historians worked hard to "undermine the validity of this clause" and in doing so "found a ready acceptance among 'revisionist' writers in France, Britain, and the USA. "[31] Sally Marks comments that "German politicians and propagandists fulminated endlessly about 'unilateral war guilt', convincing many who had not read the treaties of their injustice on this point".[140]

Additional resentment came from the perceived unfair treatment received in regards to ethnic Germans outside of Germany’s borders. National self-determination was "at the heart of the peacemaking" and while there was polls showing "overwhelming majorities" within the Sudetenland and Austria wanting to merge with Germany, this was firmly forbidden.[37][58] The view held was that "the self-determination granted to others was denied to fellow-Germans".[58] "More traumatic" was the revival of Poland and the granting of "substantial portions" of Prussian land to the new Polish state.[141]

With Germany having not been invaded and German soldiers still based in France at the end of the war, the German High Command and right wing politicians claimed that Germany had not been defeated on the field of battle but rather by left wing politicians and the collapse of the home front. This position gave rise to the Stab-in-the-back myth.[21][142] With time, the list of those who had betrayed Germany increased to include communists, "milksops", and German Jews.[143]

Aftermath

Territorial changes

Robert Peckham notes that the issue of Schleswig-Holstein "was premised on a gross simplification of the region’s history". The plebiscite presented two options: choose between Denmark or Germany. Peckham asserts that "Versailles ignored any possibility of there being a third way: the kind of compact represented by the Swiss Federation; a bilingual or even trilingual Schleswig-Holsteinian state" or other options such as "a Schleswigian state in a loose confederation with Denmark or Germany, or an autonomous region under the protection of the League of Nations." In early 1920, a referendum was held in Schleswig. The "northern, Danish-speaking part, voted for Denmark, while the southern, German speaking part voted for Germany" resulting in the territory being split between both countries. "Holstein remained German without a referendum".[75]

On 11 July 1920, the East Prussia plebiscite was held. There was a 90 per cent turn out with 99.3 per cent of the population wishing to remain with Germany. Historian Richard Blanke comments that "no other contested ethnic group has ever, under un-coerced conditions, issued so one-sided a statement of its national preference".[144] However, Richard Debo disagrees. He notes that "both Berlin and Warsaw believed the Soviet invasion of Poland had influenced the East Prussian plebiscites. Poland appeared so close to collapse that even Polish voters had cast their ballots for Germany".[145]

Following plebiscites in Eupen, Malmedy, and Prussian Moresnet, the League of Nations allotted these territories to Belgium on 20 September 1920. Over the next two years a Boundary Commission conducted work, completing its assignment on 6 November 1922. On 15 December 1923, the German Government recognized the new border between the two countries.[146]

The transfer of the Hultschin area, of Silesia, to Czechoslovakia was completed on 3 February 1921.[147]

Between 1919 and 1921 violence broke out between Poles and Germans within the province of Upper Silesia. Three uprisings took place as Germany and Poland fought for control of the region.[148][149] While German and Polish Silesians fought one another, German and Polish troops – who had little or no connection to the region – intervened "in the name of the 'national interest'". Philipp Ther comments that "the major cause of the violence, then, was the choice not to demobilize troops who had fought in World War I, not a nationalist mobilization of the population in Upper Silesia".[149] In March 1921, the plebiscite in Upper Silesia was conducted by an Inter-allied Commission of Britain, France, and Italy, who were also governing the area following the implantation of the Treaty of Versailles. While there had been violence in the region, "the election itself took place without incident" and close to 60 per cent of the population voted to remain with Germany.[150] Following the vote, the League of Nations debated how the resulted "should be applied", if the entire area should be transferred to Germany or the area split in regards to how individual sections of the area had voted. While the debate was underway, "the Poles invaded the territory" effecting the final outcome.[151] In 1922, Upper Silesia was partitioned by the League of Nations. The northwestern section (Oppeln) of the district remained with Germany while the southeastern part (Silesia Province) was transferred to Poland.[148] Blanke observes "given that the electorate was at least 60% Polish-speaking, this means that about one 'Pole' in three voted for Germany". He further notes that "most Polish observers and historians" have concluded that the outcome of plebiscite was due to "unfair German advantages of incumbency and socio-economic position" and have also alleged "coercion of various kinds even in the face of an allied occupation regime" occurred, and that Germany granted votes to those "who had been born in Upper Silesia but no longer resided there". Blanke concludes that despite these protests "there is plenty of other evidence, including Reichstag election results both before and after 1921 and the large-scale emigration of Polish-speaking Upper Silesians to Germany after 1945, that their identification with Germany in 1921 was neither exceptional nor temporary". He further notes "here was a large population of Germans and Poles – not coincidentally, of the same Catholic religion – that not only shared the same living space but also came in many cases to see themselves as members of the same national community".[150] Prince Eustachy Sapieha, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, alleged that Soviet Russia "appeared to be intentionally delaying negotiations" to end the Polish-Soviet War "with the object of influencing the Upper Silesian plebiscite".[145] Once the region was partitioned, both "Germany and Poland attempted to 'cleanse' their shares of Upper Silesia" via oppression resulting in Germans migrating to Germany and Poles migrating to Poland. Despite the oppression and migration, Opole Silesia "remained ethnically mixed."[148]

Memel remained under the authority of the League of Nations, with a French military garrison, until January 1923.[152] On 9 January 1923, Lithuanian forces invaded the territory.[153] The French garrison withdrew, and in February 1923, the Allies agreed to attach "Memel as an autonomous territory to Lithuania".[152] On 8 May 1924, after negotiations between the Lithuanian Government and the Conference of Ambassadors, and action taken by the League of Nations, the annexation of the territory was ratified.[153] In exchange, "Lithuania accepted the Memel Statute, a power-sharing arrangement to protect non-Lithuanians in the territory and its autonomous status. ... Overall responsibility for the territory remained with the great powers", however, the League of Nations "preferred to have Memel disputes between Germans and Lithuanians settled locally, and until 1929 they most were, due to the determination of the German prime minister, Gustav Stresemann, to make the Memel Statute and its power-sharing arrangement succeed." Until 1929, this arrangement worked and both countries "agreed to enhance their economic linkages while working around their differences" and the League of Nations "served during this period largely as a check against German-Lithuanian failure to reach solutions".[152]

On 13 January 1935, a plebiscite was held within the Saar region. 528,105 votes were cast, with 477,119 votes being in favor of union with Germany – 90 per cent of the valid ballot. 46,613 votes were cast for the status quo, and only 2,124 for union with France. The region was returned to Germany on 1 March 1935. Frank Russell notes that the Saar inhabitants "were not terrorized at the polls" and concludes that the "totalitarian German regime was not distasteful to most of the Saar inhabitants and that they preferred it even to an efficient, economical, and benevolent international rule." When the outcome of the vote became known, 4,100 (including 800 refugees who had previously fled Germany) residents fled over the border into France.[154]

Reparations

In January 1921, the Inter-Allied Reparations Commission established the reparation figure Germany had to pay. The figure was set at 132 billion marks, divided into three categories. The first category, 'A Bonds', amounted to 12 billion gold marks. The second category, 'B Bonds', amounted to a further 38 billion marks. The final category, 'C Bond's, contained the remaining two thirds of the total sum. However, as historian and reparation expert Sally Marks notes, "Allied experts knew that Germany could not pay" the entire sum thus the third category was "deliberately designed to be chimerical" and its "primary function was to mislead public opinion ... into believing the" total sum "was being maintained."[155] Bell notes that the 'C Bonds' essentially "amounted to [the] indefinite postponement" of that figure.[123] The combined total of the 'A' and 'B' Bonds, which were genuine, "represented the actual Allied assessment of German capacity to pay" and "therefore ... represented the total German reparations" figure. Therefore, Germany was only required to pay 50 billion marks (12.5 billion dollars), "an amount smaller than what Germany had ... offered to pay".[155] Furthermore, Germany did not have to pay this entire figure in cash. While there was to be periodic cash payments, the gold value of material shipments were to be credited against the total sum. These material shipments included coal, timber, chemical dyes, pharmaceutical drugs, livestock, agricultural machines, construction material, and factory machinery. Helping to restore the Library of Louvain was credited towards the overall reparation sum, as did some of the territorial changes imposed upon Germany by the treaty.[156] The highly publicized rhetoric of 1919 about paying for all the damages and all the veterans' benefits was irrelevant to the total, but it did affect how the recipients spent their share. Austria, Hungary, and Turkey were also supposed to pay reparations. However, they were so impoverished following the war that they in fact paid very little before their debts were written off. Germany was the only defeated country rich enough to pay anything.[157]

In January 1923, following Germany failing to make reparation payments in kind, French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr with the goal of forcing Germany to resume payments. The French saw this as an opportunity to either make Germany continue paying or inflict serious damage upon the German economy.[158] Later in the year, on the initiative of the British, a committee (containing American, Belgian, British, French, Germany, and Italian experts) was formed to consider "from a purely technical standpoint" how to balance the German budget, stabilize the German economy, and set an achievable level of reparations. The committee was chaired by, the American banker and Director of the US Bureau of the Budget, Charles G. Dawes. The recommendations of the committee became known as the Dawes Plan and were accepted during 1924. The plan called for the withdrawal of French troops from the Ruhr (which the French agreed to), a German bank independent of the German government with a ruling body that was at least 50 per cent non-German, and plans to stabilize the German currency. The Dawes Plan "left the total [reparations] unchanged", but organized a new scheme of payments. Within the first year of the plan taking effect, Germany would have to pay 1,000 million marks rising to 2,500 million marks per year by the fifth year following the acceptance of the plan. To help make payments, a Reparation Agency was established. It contained Allied representatives to organize the payment of reparations. To facilitate the Dawes Plan, a loan of 800 million marks was to be raised (over 50 per cent coming from the United States, 25 per cent from Britain, and the rest from other European countries) to back the German currency and to aid in reparation payments.[159] For the establishment of the plan and for contributing to "reducing the tension between Germany and France" Charles Dawes received the Nobel Peace Prize for 1925. [160]

In February 1929, a new committee was formed to reexamine the reparation situation. Chaired by Owen D. Young, the committee presented its findings in June, and in May 1930 the Young Plan was accepted and put into effect. It called for the end of "foreign surveillance of German finances", the withdrawal of the Reparations Agency, a 25 per cent reduction in the level of reparations[161] to a total sum of 26,350 million dollars[162] and a new scheme of payments that were to be completed by 1988: "the first mention of a final date."[161] In 1932, the Lausanne Conference "cancelled reparations altogether".[163] By this point Germany had paid 20.598 billon gold marks in reparations.[164] With the rise of Adolf Hitler, all bonds and loans that had been issued and taken out during the 1920s and early 1930s were cancelled. David Andelman notes "refusing to pay doesn’t make an agreement null and void. The bonds, the agreement, still exist." Thus, following the Second World War, at the London Conference in 1953, Germany agreed to resume payment on the money borrowed. On 3 October 2010, Germany made the final payment on these bonds.[165]

The Rhineland

Following the end of the war, the United States Third Army entered the Rhineland with 200,000 men to enforce the terms of the armistice. In June 1919, following the signing of the treaty, the Third Army was deactivated.[166] The American occupation force was steadily scaled down. By 1920, 15,000 men remained. In the final months of Woodrow Wilson’s presidency, he successfully reduced the American garrison to 6,500 men before President Warren G. Harding was inaugurated.[167] On 7 January 1923, in response to the Franco-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr,[168] the US senate passed legislation to withdraw to the remaining force.[169] On 24 January, the American garrison started their withdrawal from the Rhineland, with the final troops leaving in early February.[170] The British, likewise, disapproved of the Franco-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr.[168] Withdrawing the British garrison was considered, but was found to be unwise. It was deemed that as long as the British army "remained on the Rhine it could act as a check on the French" and stop the French from carrying out their policy "of establishing an autonomous Rhineland Republic."[171]

At a conference held in The Hague in August 1929 to further discuss the Young Plan, the German Prime Minister Gustav Stresemann and his French counterpart Aristide Briand negotiated the early withdrawal of Allied forces from the Rhineland.[172] Briand, who became known as the 'apostle of peace' agreed on an early withdrawal and gave Stresemann his assurance that the French army would vacate the Rhineland no later than 30 June 1930.[173] On 30 June 1930, after speeches and the lowering of flags, the final remnants of the Anglo-French-Belgian occupation force withdrew from Germany.[174]

The Locarno Treaties

On 16 October 1925, on the initiative of the British foreign minister Austen Chamberlain, a meeting was held at the Swiss town of Locarno between Belgian, British, French, German, and Italian representatives. The outcome of this meeting, the Locarno Treaties, were signed on 1 December in London, United Kingdom. The German government accepted her current western borders, as set out by the Treaty of Versailles, and also accepted the Rhineland as a demilitarized zone. What had "previously [been] regarded as only part of the diktat of Versailles" was now "freely accepted" by the German government during the Locarno conference.[175] Italy and the United Kingdom were the guarantees of this agreement and the border, "in effect protecting France and Germany from attack by each other".[176] Chamberlain called the Locarno Treaty as "the real dividing-line between the years of war and the years of peace".[175] Stresemann observed that "Locarno may be interpreted as signifying that the States of Europe at last realize that they cannot go on making war upon each other without being involved in common ruin".[176] As well as the treaty, the German and French foreign ministers – Stresemann and Briand – had started to develop a strong relationship "perhaps amounting to friendship".[175] For their efforts in attempting to foster reconciliation between Germany and France, Chamberlain, Briand, and Stresemann were all awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace.[176]

The Locarno Treaties "marked the rehabilitation of Germany as a full member of the international community" and German joined the League of Nations in 1926.[176] The treaty was accompanied by additional agreements. A Franco-German committee aimed to mend relations between French and German Catholics. Industrialists from Belgian, France, Germany, and Luxembourg signed an agreement in September 1926 to create an iron and steel cartel regulating annual production and its division among the four countries. German signed a series of treaties with Czechoslovakia, France, and Poland "laying down that certain types of disputes between the signatories should be submitted to outside arbitration." France signed "treaties of mutual guarantee[s]" with Czechoslovakia and Poland intended to counter the "obvious gap left by Locarno, which was that it concerned only Western Europe."[177]

Violations of the treaty

During 1920, Hans von Seeckt "re-established a clandestine general staff system."[178] In March of the same year, 18,000 German troops entered the Rhineland to "quell possible communist unrest" and in doing so violated the demilitarized zone. French troops therefore extended their occupation zone further into Germany until the German troops withdrew. In violation of the disarmament clauses of the treaty, German military and government officials "deliberately planned systematic violations of the effectives clauses of the treaty" such as actively avoiding to meet disarmament deadlines, refusing Allied officials access to military facilities (who had the right to view such facilities to ensure the Germans were compiling with the disarmament protocols), continuing "illegal Krupp production" and keeping "hidden weapon caches".[179] As nothing within the treaty forbade German companies from producing war material outside of Germany, German companies moved abroad to continue weapons manufacturing for Germany. Plants were established in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Sweden. The Swedish arms company Bofors, was bought out by Krupp and in 1921 German troops were sent to Sweden to test weapons.[180]

During the Genoa Conference, an economic conference held in Italy in 1922, representatives from the Weimar Republic and the Soviet Union signed the Treaty of Rapallo on 16 April. The treaty re-established full diplomatic relations between Germany and the Soviet Union, renounced compensation for war damages, renounced all claims – national or private – against one another, set favorable terms for trade, and stated both countries would supply each other’s economic requirements.[181] While the Soviet government denied that there was any secret military clauses to the treaty, the signing of the treaty resulted in "increasing contact, secret in nature, between Soviet and German military and industrial interests."[182] Historian P.M.H Bell comments this allowed "Germany to develop weapons in the USSR".[183] In breach of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany established three secret training areas inside the Soviet Union: one for aviation, chemical, and tank warfare. The German military were able to experiment "with advanced war techniques" and train their military personnel.[184]

In 1923, the British newspaper The Times published two articles claiming Germany had "personnel, clothing, and armaments for 800,000 men and was transferring army staff to civilian positions." It also warned of the "danger of the military nature" of the German police force, and claimed Germany was "attempting to establish an army based on the historic Krümper system".[185][nb 4]

In 1925, with "the end of the Allied disarmament operations" in sight, German companies "drafted plans for tanks and artillery". In January 1927, following the withdrawal of the disarmament committee, "Krupp increased [the] illegal production of artillery and armor plate". Gustav Krupp later claimed he had duped the Allies throughout the 1920s and prepared the German military for the future.[180] Throughout the 1920s, Germany sold weapons to China. In 1925, over half of the weapons China imported were from Germany worth a total of 13 million Reichsmarks.[187] By 1936, arms deliveries to China had increased to 23,748,000 Reichmarks and the following year 82,788,604.[188]

During December 1931, the German military finalized a second rearmament plan, calling for the spending of 480 million Reichsmarks over the course of five years. A 'billion Reichsmark programme' "set out the extra spending on industrial inferstructure required to keep" an enlarged military "permanently in the field." However, since the plan "required no expansion of the peacetime strength of the Reichswehr" these spending plans "remained at least formally within the terms of Versailles." On 7 November 1932, Kurt von Schleicher authorized the Umbau Plan. This plan, an outright breech of the treaty, "called for the creation of a standing army of 21 divisions based around a cadre of 147,000 professional soldiers and a substantial militia". Towards the end of the year at the World Disarmament Conference, Germany withdrew from the talks in a bid to force France and the United Kingdom to accept German equality of status.[189] In response, the United Kingdom attempted to get Germany to return with the promise of "equality of rights in armaments in a system which would provide security of all nations" and later proposed "an increase in the German Army from 100,000 to 200,000, while the French Army would be reduced." Further negotiations resulted in the agreement "that Germany should have an air force half the size of the French." Bell comments that while the British government already knew Germany was rearming, "public respectability was thus conferred on the idea of German rearmament".[190] By 1933, Franco-German relations were deteriorating, the World Economic Conference broke up in disorder and the "spirit of Locarno fizzled out."[191]