Mohammad Najibullah

Mohammad Najibullah | |

|---|---|

محمد نجیبالله احمدزی | |

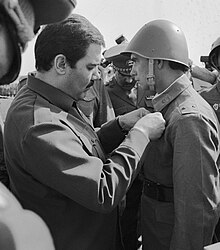

Najibullah in 1991 | |

| General Secretary of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan | |

| In office 4 May 1986 – 16 April 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Babrak Karmal |

| Succeeded by | Party abolished |

| 2nd President of Afghanistan | |

| In office 30 November 1987 – 16 April 1992 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by | Burhanuddin Rabbani |

| Chairman of the Presidium of the Revolutionary Council | |

| In office 30 September 1987 – 30 November 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Haji Mohammad Chamkani |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as president) |

| Director of the State Intelligence Agency (KHAD) | |

| In office 11 January 1980 – 21 November 1985 | |

| Leader | Babrak Karmal (as General Secretary) |

| Preceded by | Assadullah Sarwari |

| Succeeded by | Ghulam Faruq Yaqubi |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 6 August 1947 Gardez, Kingdom of Afghanistan[5] |

| Died | 27 September 1996 (aged 49) Kabul, Afghanistan |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Resting place | Gardez, Paktia, Afghanistan |

| Political party | People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (Parcham) |

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Afghanistan |

| Branch/service | Afghan National Army |

| Years of service | 1965–1992 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | |

Mohammad Najibullah Ahmadzai (Pashto/Template:Lang-prs, Pashto pronunciation: [mʊˈhamad nad͡ʒibʊˈlɑ ahmadˈzai]; 6 August 1947 – 27 September 1996),[7] commonly known as Dr. Najib, was an Afghan politician who served as the General Secretary of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan, the leader of the one-party ruling Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from 1986 to 1992 and as well as the President of Afghanistan from 1987 until his resignation in April 1992, shortly after which the mujahideen took over Kabul. After a failed attempt to flee to India, Najibullah remained in Kabul. He lived in the United Nations headquarters until his assassination by the Taliban after their capture of the city.[8]

A graduate of Kabul University, Najibullah held different careers under the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). Following the Saur Revolution and the establishment of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, Najibullah was a low profile bureaucrat. He was sent into exile as Ambassador to Iran during Hafizullah Amin's rise to power. He returned to Afghanistan following the Soviet intervention which toppled Amin's rule and placed Babrak Karmal as head of the state, the party and the government. During Karmal's rule, Najibullah became head of the KHAD, the Afghan equivalent of the Soviet KGB. He was a member of the Parcham faction led by Karmal. During Najibullah's tenure as KHAD head, it became one of the most brutally efficient governmental organs. Because of this, he gained the attention of several leading Soviet officials, such as Yuri Andropov, Dmitriy Ustinov and Boris Ponomarev. In 1981, Najibullah was appointed to the PDPA Politburo. In 1985, Najibullah stepped down as the state security minister to focus on PDPA politics; he had been appointed to the PDPA Secretariat. Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, also the last Soviet leader, was able to get Karmal to step down as PDPA General Secretary in 1986, and replace him with Najibullah. For a number of months, Najibullah was locked in a power struggle against Karmal, who still retained his post of Chairman of the Revolutionary Council. Najibullah accused Karmal of trying to wreck his policy of National Reconciliation, a series of efforts by Najibullah to end the conflict.

During his tenure as leader of Afghanistan, the Soviets began their withdrawal, and from 1989 until 1992, his government tried to solve the ongoing civil war without Soviet troops on the ground. While direct Soviet assistance ended with the withdrawal, the Soviet Union still supported Najibullah with economic and military aid, while Pakistan and the United States continued their support for the mujahideen. Throughout his tenure, he tried to build support for his government via the National Reconciliation reforms by distancing from socialism in favor of Afghan nationalism, abolishing the one-party state and letting non-communists join the government. He remained open to dialogue with the mujahideen and other groups, made Islam an official religion, and invited exiled businessmen back to re-take their properties.[9] In the 1990 constitution, all references to communism were removed and Islam became the state religion. For various reasons, such changes did not win Najibullah any significant support. Following the August Coup in Moscow[10] and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991, Najibullah was left without foreign aid. This, coupled with the internal collapse of his government (following the defection of general Abdul Rashid Dostum), led to his resignation in April 1992. In 1996, he was tortured and killed by the Taliban.

In 2017, the pro-Najibullah Watan Party was created as a continuation of Najibullah's party.[11]

Early life and career

Najibullah was born on 6 August 1947 in the city of Gardez, Paktia Province, in the Kingdom of Afghanistan.[5] His ancestral village of Najibqilla is located between the towns of Gardez and Said Karam in an area known as Mehlan.[12] He belonged to the Ahmadzai Ghilji tribe of Pashtuns.[13]

He was educated at Habibia High School in Kabul, at St. Joseph's School in Baramulla, Jammu and Kashmir, India, and at Kabul University where he began studying in 1964 and completed his Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) in 1975. However, he never practiced medicine. In 1965, during his study in Kabul, Najibullah joined the Parcham (Banner) faction of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) and was twice imprisoned for political activities. He served as Babrak Karmal's close associate and bodyguard during the latter's tenure in the lower house of parliament (1965–1973).[14] In 1977, he was elected to the Central Committee. In April 1978, the PDPA took power in Afghanistan, with Najibullah a member of the ruling Revolutionary Council. However, the Khalq (People's) faction of the PDPA gained supremacy over his own Parcham (Banner) faction, and after a brief stint as Ambassador to Iran, he was dismissed from government and went into exile in Europe, until the Soviet Union intervened in 1979 and supported a Parcham-dominated government.[5]

Under Karmal: 1979–1986

Minister of State Security: 1980–1985

In 1980, Najibullah was appointed the head of KHAD, the Afghan equivalent to the Soviet KGB,[15] and was promoted to the rank of Major General.[13] He was appointed following lobbying from the Soviets, including Yuri Andropov, then KGB Chairman. During his six years as head of KHAD he had two to four deputies under his command, who in turn were responsible for an estimated 12 departments. According to evidence, Najibullah was dependent on his family and his professional network, and more often than not appointed people he knew to top positions within the KHAD.[15] In June 1981, Najibullah, along with Mohammad Aslam Watanjar, a former tank commander and the then Minister of Communications and Major General Mohammad Rafi, the Minister of Defence were appointed to the PDPA Politburo.[16] Under Najibullah, KHAD's personnel increased from 120 to 25,000 to 30,000.[17] KHAD employees were amongst the best-paid government bureaucrats in communist Afghanistan, and because of it, the political indoctrination of KHAD officials was a top priority. During a PDPA conference, Najibullah, talking about the indoctrination programme of KHAD officials, said "a weapon in one hand, a book in the other."[18] Counter-insurgency activities launched by KHAD reached its peak under Najibullah.[19] He reported directly to the Soviet KGB, and a big part of KHAD's budget came from the Soviet Union itself.[20]

As time would show, Najibullah was very efficient, and during his tenure as leader of KHAD, thousands were arrested, tortured, and executed.[13] KHAD targeted anti-communist citizens, political opponents, and educated members of society. It was this efficiency which made him interesting to the Soviets.[13] Because of this, KHAD became known for its ruthlessness. During his ascension to power, several Afghan politicians did not want Najibullah to succeed Babrak Karmal because Najibullah was known for exploiting his powers for his own benefit. Additionally, during his period as KHAD chief, the Pul-i Charki had become the home of several Khalqist politicians. Another problem was that Najibullah allowed graft, theft, bribery and corruption on a scale not seen previously.[21] As would later be proven by the power struggle he had with Karmal after becoming PDPA General Secretary, despite Najibullah heading the KHAD for five years, Karmal still had sizeable support in the organisation.[22]

Rise to power: 1985–1986

| History of Afghanistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

He was appointed to the PDPA Secretariat in November 1985.[23] Najibullah's ascent to power was proven by turning KHAD from a government organ to a ministry in January 1986.[24] With the situation in Afghanistan deteriorating, and the Soviet leadership looking for ways to withdraw, Mikhail Gorbachev wanted Karmal to resign as PDPA General Secretary. The question of who was to succeed Karmal was hotly debated, but Gorbachev supported Najibullah.[25] Yuri Andropov, Boris Ponomarev and Dmitriy Ustinov all thought highly of Najibullah, and negotiations of who would succeed Karmal might have begun as early as 1983. Despite this, Najibullah was not the only choice the Soviets had. A GRU report argued that he was a Pashtun nationalist, a stance which could decrease the regime's popularity even more. The GRU preferred Assadullah Sarwari, earlier head of ASGA, the pre-KHAD secret police, who they believed would be better able to balance between the Pashtuns, Tajiks and Uzbeks. Another viable candidate was Abdul Qadir, who had been a participant in the Saur Revolution.[26] Najibullah succeeded Karmal as PDPA General Secretary on 4 May 1986 at the 18th PDPA meeting, but Karmal still retained his post as Chairman of the Presidium of the Revolutionary Council.[27]

On 15 May, Najibullah announced that a collective leadership had been established, which was led by himself consisted of himself as head of party, Karmal as head of state and Sultan Ali Keshtmand as Chairman of the Council of Ministers.[28] When Najibullah took the office of PDPA General Secretary, Karmal still had enough support in the party to disgrace Najibullah. Karmal went as far as to spread rumours that Najibullah's rule was little more than an interregnum, and that he would soon be reappointed to the general secretaryship. As it turned out, Karmal's power base during this period was KHAD.[27] The Soviet leadership wanted to ease Karmal out of politics, but when Najibullah began to complain that he was hampering his plans of National Reconciliation, the Soviet Politburo decided to remove Karmal; this motion was supported by Andrei Gromyko, Yuli Vorontsov, Eduard Shevardnadze, Anatoly Dobrynin and Viktor Chebrikov. A meeting in the PDPA in November relieved Karmal of his Revolutionary Council chairmanship, and he was exiled to Moscow where he was given a state-owned apartment and a dacha.[29] In his position as Revolutionary Council chairman Karmal was succeeded by Haji Mohammad Chamkani, who was not a member of the PDPA.[19]

In 1986, there were more than 100,000 political prisoners and there had been more than 16,500 extrajudicial executions. Its main objectives were the opponents of communism and the most educated classes in society.[30]

Leader: 1986–1992

National Reconciliation

In September 1986, the National Compromise Commission (NCC) was established on the orders of Najibullah. The NCC's goal was to contact counter-revolutionaries "in order to complete the Saur Revolution in its new phase." Allegedly, an estimated 40,000 rebels were contacted by the government. At the end of 1986, Najibullah called for a six-months ceasefire and talks between the various opposition forces, this was part of his policy of National Reconciliation. The discussions, if fruitful, would lead to the establishment of a coalition government and be the end of the PDPA's monopoly of power. The programme failed, but the government was able to recruit disillusioned mujahideen fighters as government militias.[19] In many ways, the National Reconciliation led to an increasing number of urban dwellers to support his rule, and the stabilisation of the Afghan defence forces.[31]

In September 1986, a new constitution was written, which was adopted on 29 November 1987.[32] The constitution weakened the powers of the head of state by cancelling his absolute veto. The reason for this move, according to Najibullah, was the need for real-power sharing. On 13 July 1987, the official name of Afghanistan was changed from the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan to Republic of Afghanistan, and in June 1988 the Revolutionary Council, whose members were elected by the party leadership, was replaced by a National Assembly, an organ in which members were to be elected by the people. The PDPA's socialist stance was denied even more than previously, in 1989 the Minister of Higher Education began to work on the "de-Sovietisation" of universities, and in 1990 it was even announced by a party member that all PDPA members were Muslims and that the party had abandoned Marxism. Many parts of the Afghan government's economic monopoly was also broken, this had more to do with the tight situation than any ideological conviction. Abdul Hakim Misaq, the Mayor of Kabul, even stated that traffickers of stolen goods would not be prosecuted by law as long as their goods were given to the market. Yuli Vorontsov, on Gorbachev's orders, was able to get an agreement with the PDPA leadership to offer the posts of Gossoviet chairman (the state planning organ), the Council of Ministers chairmanship (head of government), ministries of defence, state security, communications, finance, presidencies of banks and the Supreme Court. The PDPA still demanded it held on to all deputy ministers, retained its majority in the state bureaucracy and that it retained all its provincial governors.[33] The government was not willing to concede all of these positions, and when the offer was broadcast, the ministries of defence and state security.[34]

Elections: 1987 and 1988

Local elections were held in 1987. It began when the government introduced a law permitting the formation of other political parties, announced that it would be prepared to share power with representatives of opposition groups in the event of a coalition government, and issued a new constitution providing for a new bicameral National Assembly (Meli Shura), consisting of a Senate (Sena) and a House of Representatives (Wolesi Jirga), and a president to be indirectly elected to a 7-year term.[35] The new political parties had to oppose colonialism, imperialism, neo-colonialism, Zionism, racial discrimination, apartheid and fascism. Najibullah stated that only the extremist part of the opposition could not join the planned coalition government. No parties had to share the PDPA's policy or ideology, but they could not oppose the bond between Afghanistan and the Soviet Union. A parliamentary election was held in 1988. The PDPA won 46 seats in the House of Representatives and controlled the government with support from the National Front, which won 45 seats, and from various newly recognized left-wing parties, which had won a total of 24 seats. Although the election was boycotted by the Mujahideen, the government left 50 of the 234 seats in the House of Representatives, as well as a small number of seats in the Senate, vacant in the hope that the guerrillas would end their armed struggle and participate in the government. The only armed opposition party to make peace with the government was Hizbollah, a small Shi'a party not to be confused with the bigger party in Iran or the Lebanese organization.[36]

Emergency

Several figures of the intelligentsia took Najibullah's offer seriously, even if they sympathised or were against the regime. Their hopes were dampened when the Najibullah government introduced the state of emergency on 18 February 1989, four days after the Soviet withdrawal. 1,700 intellectuals were arrested in February alone, and until November 1991 the government still supervised and restricted freedom of speech. Another problem was that party members took his policy seriously too, Najibullah recanted that most party members felt "panic and pessimism." At the Second Conference of the party, the majority of members, maybe up to 60 percent, were radical socialists. According to Soviet advisors (in 1987), a bitter debate within the party had broken out between those who advocated the Islamisation of the party and those who wanted to defend the gains of the Saur Revolution. Opposition to his policy of National Reconciliation was met party-wide, but especially from Karmalists. Many people did not support the handing out of the already small state resources the Afghan state had at its disposal. On the other side, several members were proclaiming anti-Soviet slogans as they accused the National Reconciliation programme to be supported and developed by the Soviet Union.[37] Najibullah reassured the inter-party opposition that he would not give up the gains of the Saur Revolution, but to the contrary, preserve them, not give up the PDPA's monopoly on power, or to collaborate with reactionary Mullahs.[38]

An Islamic state

During Babrak Karmal's later years, and during Najibullah's tenure, the PDPA tried to improve their standing with Muslims by moving, or appearing to move, to the political centre. They wanted to create a new image for the party and state. In 1987, Najibullah re-added Ullah to his name to appease the Muslim community. Communist symbols were either replaced or removed. These measures did not contribute to any notable increase in support for the government, because the mujahideen had a stronger legitimacy to protect Islam than the government; they had rebelled against what they saw as an anti-Islamic government, that government was the PDPA.[39] Islamic principles were embedded in the 1987 constitution, for instance, Article 2 of the constitution stated that Islam was the state religion, and Article 73 stated that the head of state had to be born into a Muslim Afghan family. The 1990 constitution stated that Afghanistan was an Islamic state, and the last references to communism were removed.[40] Article 1 of the 1990 Constitution said that Afghanistan was an "independent, unitary and Islamic state."[32]

Economic policies

Najibullah continued Karmal's economic policies. The augmenting of links with the Eastern Bloc and the Soviet Union continued, and so did bilateral trade. He encouraged the development of the private sector in industry. The Five-Year Economic and Social Development Plan which was introduced in January 1986 continued until March 1992, one month before the government's fall. According to the plan, the economy, which had grown less than 2 percent annually until 1985, would grow 25 percent in the plan. Industry would grow 28 percent, agriculture 14–16 percent, domestic trade by 150 percent and foreign trade with 15 percent. As expected, none of these targets were met, and 2 percent growth annually which had been the norm before the plan continued under Najibullah.[41] The 1990 constitution gave due attention to the private sector. Article 20 was about the establishment of private firms, and Article 25 encouraged foreign investments in the private sector.[32]

Afghan–Soviet relations

Soviet withdrawal

While he may have been the de jure leader of Afghanistan, Soviet advisers still did the majority of work when Najibullah took power. As Gorbachev remarked "We're still doing everything ourselves [...]. That's all our people know how to do. They've tied Najibullah hand and foot."[42] Fikryat Tabeev, the Soviet ambassador to Afghanistan, was accused of acting like a governor general by Gorbachev. Tabeev was recalled from Afghanistan in July 1986, but while Gorbachev called for the end of Soviet management of Afghanistan, he could not help but to do some managing himself. At a Soviet Politburo meeting, Gorbachev said "It's difficult to build a new building out of old material [...] I hope to God that we haven't made a mistake with Najibullah."[42] As time would prove, the problem was that Najibullah's aims were the opposite of the Soviet Union's; Najibullah was opposed to a Soviet withdrawal, the Soviet Union wanted a Soviet withdrawal. This was logical, considering the fact that the Afghan military was on the brink of dissolution. The only means of survival seemed to Najibullah was to retain the Soviet presence.[42] In July 1986 six regiments, which consisted up to 15,000 troops, were withdrawn from Afghanistan. The aim of this early withdrawal was, according to Gorbachev, to show the world that the Soviet leadership was serious about leaving Afghanistan.[43] The Soviets told the United States Government that they were planning to withdraw, but the United States Government did not believe them. When Gorbachev met with Ronald Reagan during his visit the United States, Reagan called for the dissolution of the Afghan army.[44]

On 14 April 1988, the Afghan and Pakistani governments signed the Geneva Accords, and the Soviet Union and the United States signed as guarantors; the treaty specifically stated that the Soviet military had to withdraw from Afghanistan by 15 February 1989. Gorbachev later confided to Anatoly Chernyaev, a personal advisor to Gorbachev, that the Soviet withdrawal would be criticised for creating a bloodbath which could have been averted if the Soviets stayed.[45] During a Politburo meeting Eduard Shevardnadze said "We will leave the country in a deplorable situation",[46] and further talked about the economic collapse, and the need to keep at least 10 to 15,000 troops in Afghanistan. In this Vladimir Kryuchkov, the KGB Chairman, supported him. This stance, if implemented, would be a betrayal of the Geneva Accords just signed.[46] During the second phase of the Soviet withdrawal, in 1989, Najibullah told Valentin Varennikov openly that he would do everything to slow down the Soviet departure. Varennikov in turn replied that such a move would not help, and would only lead to an international outcry against the war. Najibullah would repeat his position later that year, to a group of senior Soviet representatives in Kabul. This time Najibullah stated that Ahmad Shah Massoud was the main problem, and that he needed to be killed. In this, the Soviets agreed,[47] but repeated that such a move would be a breach of the Geneva Accords; to hunt for Ahmad Shah Massoud so early on would disrupt the withdrawal, and would mean that the Soviet Union would fail to meet its deadline for withdrawal.[48]

During his January 1989 visit to Shevardnadze, Najibullah wanted to retain a small presence of Soviet troops in Afghanistan, and called for moving Soviet bombers to military bases close to the Afghan–Soviet border and place them on permanent alert.[49] Najibullah also repeated his claims that his government could not survive if Ahmad Shah Massoud remained alive. Shevardnadze again repeated that troops could not stay, since it would lead to international outcry, but said he would look into the matter. Shevardnadze demanded that the Soviet embassy created a plan in which at least 12,000 Soviet troops would remain in Afghanistan either under direct control of the United Nations or remain as "volunteers".[50] The Soviet military leadership, when hearing of Shevardnadze's plan, became furious. But they followed orders, and named the operation Typhoon, maybe ironic considering that Operation Typhoon was the German military operation against the city of Moscow during World War II. Shevardnadze contacted the Soviet leadership about moving a unit to break the siege of Kandahar, and to protect convoys from and to the city. The Soviet leadership were against Shevardnadze's plan, and Chernyaev even believed it was part of Najibullah's plan to keep Soviet troops in the country. To which Shevardnadze replied angrily "You've not been there, [...] You've no idea all the things we have done there in the past ten years."[50] At a Politburo meeting on 24 January, Shevardnadze argued that the Soviet leadership could not be indifferent to Najibullah and his government; again, Shevardnadze received support from Kryuchkov. In the end Shevardnadze lost the debate, and the Politburo reaffirmed their commitment to withdraw from Afghanistan.[51] There was still a small presence of Soviet troops after the Soviet withdrawal; for instance, parachutists who protected the Soviet embassy staff, military advisors and special forces and reconnaissance troops still operated in the "outlying provinces", especially along the Afghan–Soviet border.[52]

Aid

Soviet military aid continued after their withdrawal, and massive quantities of food, fuel, ammunition and military equipment was given to the government. Varennikov visited Afghanistan in May 1989 to discuss ways and means to deliver the aid to the government. In 1990, Soviet aid amounted to an estimated 3 billion United States dollars. As it turned out, the Afghan military was entirely dependent on Soviet aid to function.[53] When the Soviet Union was dissolved on 26 December 1991, Najibullah turned to former Soviet Central Asia for aid. These newly independent states had no wish to see Afghanistan being taken over by religious fundamentalists, and supplied Afghanistan with 6 million barrels of oil and 500,000 tons of wheat to survive the winter.[54]

After the Soviets

With the Soviets' withdrawal in 1989, the Afghan army was left on its own to battle the insurgents. The most effective, and largest, assaults on the mujahideen were undertaken during the 1985–86 period. These offensives had forced the mujahideen on the defensive near Herat and Kandahar.[55] The Soviets ensued a bomb and negotiate during 1986, and a major offensive that year included 10,000 Soviet troops and 8,000 Afghan troops.[56]

The Pakistani people and establishment continued to support the Afghan mujahideen even if it was in contravention of the Geneva Accords. At the beginning, most observers expected the Najibullah government to collapse immediately, and to be replaced with an Islamic fundamentalist government. The Central Intelligence Agency stated in a report that the new government would be ambivalent, or even worse, hostile towards the United States.[citation needed] Almost immediately after the Soviet withdrawal, the Battle of Jalalabad broke out between Afghan government forces and the mujahideen, in cooperation with Pakistan's Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI). The offensive against the city began when the mujahideen bribed several government military officers, from there, they tried to take the airport, but were repulsed with heavy casualties. The willingness of the common Afghan government soldier to fight increased when the mujahideen began to execute people during the battle. Hamid Gul, leader of the ISI, hoped that the battle would topple Najibullah's government and create a mujahideen government seated in Jalalabad.[57] During the battle, Najibullah called for Soviet assistance. Gorbachev called an emergency session of the Politburo to discuss his proposal, but Najibullah's request was rejected. Other attacks against the city failed, and by April the government forces were on the offensive.[53] During the battle over four hundred Scud missiles were shot, which were fired by a Soviet crew which had stayed behind.[58] When the battle ended in July, the mujahideen had lost an estimated 3,000 troops. One mujahideen commander lamented "the battle of Jalalabad lost us credit won in ten years of fighting."[59] After the mujahideen's defeat in Jalalabad, Gul blamed the administration of Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto for the defeat. Bhutto eventually sacked Gul.[57]

Hardline Khalqist Shahnawaz Tanai attempted to overthrow Najibullah in a failed coup attempt in March 1990. Although Tanai and his forces failed and fled to Pakistan, the coup attempt still managed to show weaknesses in Najibullah's government.

From 1989 to 1990, the Najibullah government was partially successful in building up the Afghan defence forces. The Ministry of State Security had established a local militia force which stood at an estimated 100,000 men. The 17th Division in Herat, which had begun the 1979 Herat uprising against PDPA-rule, stood at 3,400 regular troops and 14,000 tribal men. In 1988, the total number of security forces available to the government stood at 300,000.[60] This trend did not continue, and by the summer of 1990, the Afghan government forces were on the defensive again. By the beginning of 1991, the government controlled only 10 percent of Afghanistan, the eleven-year Siege of Khost had ended in a mujahideen victory and the morale of the Afghan military finally collapsed. In the Soviet Union, Kryuchkov and Shevardnadze had both supported continuing aid to the Najibullah government, but Kryuchkov had been arrested following the failed 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt and Shevardnadze had resigned from his posts in the Soviet government in December 1990 – there were no longer any pro-Najibullah people in the Soviet leadership and the Soviet Union was in the middle of an economic and political crisis, which would lead directly to the dissolution of the Soviet Union on 26 December 1991. At the same time, Boris Yeltsin became Russia's new hope, and he had no wish to continue to aid Najibullah's government, which he considered a relic of the past. In the autumn of 1991, Najibullah wrote to Shevardnadze "I didn't want to be president, you talked me into it, insisted on it, and promised support. Now you are throwing me and the Republic of Afghanistan to its fate."[61]

Fall from power

In January 1992, the Russian government ended its aid to the Najibullah government. The effects were felt immediately: the Afghan Air Force, the most effective part of the Afghan military, was grounded due to lack of fuel. The Afghan mujahideen continued to be supported by Pakistan. Major cities were lost to the rebels. On the fifth anniversary of his policy of National Reconciliation, Najibullah blamed the Soviet Union for the disaster that had stricken Afghanistan.[61] The day the Soviet Union withdrew was hailed by Najibullah as the Day of National Salvation. But it was too late, and his government's collapse was imminent.[62]

On 18 March 1992, Najibullah offered his government's immediate resignation, and followed the United Nations (UN) plan to be replaced by an interim government with all parties involved in the struggle. The announcement daunted his supporters and led to many territories surrendering or mutinying to the Mujahideen without resistance.[63] In a serious blow, army commander Abdul Rashid Dostum decided to abandon Najibullah and join the Mujahideen coalition that was created by Ahmed Shah Massoud and Abdul Ali Mazari, meaning as many as 40,000 loyalist fighters of Dostum in the north had defected; it has been cited that Kabul being unable to grant weapons and money to Dostum persuaded him. Army chief general Mohammad Nabi Azimi was sent by Najibullah to Mazar-i-Sharif to find out what was going on, only for Azimi to also defect to the so-called "Coalition of the North".[64] Other figures also defected including foreign minister Abdul Wakil.[65] Within days, Mazar-i-Sharif was under the control of the Mujahideen coalition.[66]

In mid-April, Najibullah accepted a UN plan to hand power to a seven-man council, and several days later on 14 April, Najibullah was forced to resign on the orders of the Watan Party because of the loss of Bagram Airbase and the town of Charikar. Abdul Rahim Hatef became acting head of state following Najibullah's resignation.[67] The mujahideen forces of Massoud and the defected Dostum took Kabul shortly thereafter; most mujahideen factions later signed the Peshawar Accord, creating the new Islamic State of Afghanistan.

Final years and death

Not long before Kabul's fall, Najibullah appealed to the UN for protection after his guards fled, which was rejected.[68] However, his attempt to flee to the airport was thwarted by troops of Abdul Rashid Dostum – once loyal to him, but now allied with Ahmad Shah Massoud – who controlled the airport. At the UN compound in Kabul, while waiting for the UN to negotiate his safe passage to India, he occupied himself by translating Peter Hopkirk's book The Great Game into his mother tongue Pashto.[69] India was placed in a difficult position by deciding to allow Najibullah political asylum and safely escorting him out of the country. Supporters claimed he had always been close to India and should not be denied asylum, but others said doing so would risk antagonizing India's relationship with the new mujahideen government formed under the Peshawar Accord.[70]

India also refused to let him take refuge at the Indian embassy as it risked creating "subcontinental rivalries" and reprisals against Kabul's Indian community, arguing that Najibullah would be far safer at the UN compound. All attempts failed and he eventually sought refuge in the local UN headquarters,[71] where he would stay until 1996. In 1994, India sent senior diplomat M. K. Bhadrakumar to Kabul to hold talks with Ahmad Shah Massoud, the defence minister, to consolidate relations with the Afghan authorities, reopen the embassy, and allow Najibullah to fly to India, but Massoud refused.[72] Bhadrakumar wrote in 2016 that he believed Massoud did not want Najibullah to leave as Massoud could strategically make use of him, and that Massoud "probably harboured hopes of a co-habitation with Najib somewhere in the womb of time because that extraordinary Afghan politician was a strategic asset to have by his side".[73] At the time, Massoud was commanding the government's forces fighting the militias of Dostum and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar during the Battle of Kabul. A few months before his death, he quoted, "Afghans keep making the same mistake," reflecting upon his translation to a visitor.[74]

In September 1996, when the Taliban were about to enter Kabul,[75] Massoud offered Najibullah an opportunity to flee the capital. Najibullah refused. The reasons as to why he refused remain unclear. Massoud himself claimed that Najibullah feared that "if he fled with the Tajiks, he would be for ever damned in the eyes of his fellow Pashtuns."[76] Others, like General Tokhi, who was with Najibullah until the day before his torture and murder, stated that Najibullah mistrusted Massoud after his militia had repeatedly fired rockets at the UN compound and had effectively barred Najibullah from leaving Kabul. "If they wanted Najibullah to flee Kabul in safety," Tokhi said, "they could have provided him the opportunity as they did with other high ranking officials from the communist party from 1992 to 1996."[77] Whatever his true motivations were, when Massoud's militia went to both Najibullah and General Tokhi and asked them to flee Kabul, they rejected the offer.

Najibullah was at the UN compound when the Taliban soldiers came for him on the evening of 26 September 1996.[8] The Taliban abducted him from UN custody, castrated him, tortured him to death, and dragged his corpse behind a truck through the streets of Kabul.[78] His brother, Shahpur Ahmadzai, was given the same treatment.[79] Najibullah and Shahpur's bodies were hanged from a traffic light pole outside the Arg presidential palace the next day in order to show the public that a new era had begun. The Taliban prevented Islamic funeral prayers for Najibullah and Shahpur in Kabul, but the bodies were later handed over to the International Committee of the Red Cross who in turn sent their bodies to Gardez in Paktia Province, where both of them were buried after the Islamic funeral prayers for them by their fellow Ahmadzai tribesmen.[79]

Reactions

News of Najibullah's murder was greeted with widespread international condemnation,[80] particularly from the Muslim world.[79] The United Nations issued a statement which condemned the killing of Najibullah, and claimed that it would further destabilise Afghanistan. The Taliban responded by issuing death sentences on Dostum, Massoud and Burhanuddin Rabbani.[79] India, which had been supporting Najibullah, strongly condemned his killing and began to support Massoud's United Front/Northern Alliance in an attempt to contain the rise of the Taliban.[81]

On the 20th anniversary of his death, in 2016, Afghanistan's Research Center blamed the ISI for his death, claiming that the plan to kill Najibullah was implemented by Pakistan.[82]

On 1 June 2020, following a visit to his grave in Gardez by the Afghan National Security Advisor Hamdullah Mohib, Najibullah's widow Fatana Najib said that before constructing a mausoleum for him, the government should first investigate his assassination.[83]

Legacy

After Najibullah's death, the brutal civil war between mujahideen factions, the Taliban regime, continued fighting, and enduring problems with corruption and poverty, his image among the Afghan people dramatically improved, and Najibullah came to be seen as a strong and patriotic leader. Since the 2010s, posters and pictures of him have become a common sight in many Afghan cities.[84][85]

In 1997, the Watan Party of Afghanistan was formed and in 2003, the National United Party of Afghanistan was registered – who seek to unite former PDPA members formerly led by Mohammad Najibullah.[86]

Family

Najibullah was married on 1 September 1974 to Fatana Najib, principal of the Russian-language Peace School whom he met when she was an eighth-grade student and he was her science tutor.[87] The couple had three daughters, who were forced to leave Afghanistan after the Taliban seizure and the start of the civil war. The daughters grew up with their mother in New Delhi, India, after moving there in 1992.[88] Najibullah's oldest daughter, Heela Najibullah, was born in Kabul in 1977, studied in Switzerland and was living there as of 2017.[89] She has worked in the International Red Cross.[6] In 2006 she spoke at the summit of young UN leaders representing Afghanistan. She is currently an employee of the Transnational Foundation for Peace and Future Research in Sweden, she maintains her Twitter account.[90][91] The middle daughter, called Onai (born 1978),[87] is a Master of Architecture,[92] and the youngest daughter, Mosca Najib (born 1984),[93] is an Indian citizen and works as a photographer for the international company Weber Shandwick in Singapore.[94][95][96][97]

References

- ^ National Foreign Assessment Center (1987). Chiefs of State and Cabinet members of foreign governments. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency. p. 1. hdl:2027/uc1.c050186243.

- ^ National Foreign Assessment Center (1988). Chiefs of State and Cabinet members of foreign governments. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency. p. 1. hdl:2027/osu.32435024019804.

- ^ a b c d e f National Foreign Assessment Center (1991). Chiefs of State and Cabinet members of foreign governments. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency. p. 1. hdl:2027/osu.32435024019754.

- ^ a b c d e Whitaker, Joseph (December 1991). Whitaker's Almanac 1992 124. ISBN 978-0-85021-220-4.

- ^ a b c "Najibullah". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Heela Najibullah: From Afghan First Daughter to War Refugee | Voice of America – English".

- ^ @muskanajibullah (6 August 2019). "Happy Birthday, #Aba. I remember this day when I was sick; you sat me on your lap & held me close. You knew what it…" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b White, Terence (15 October 2001). "Flashback: When the Taleban took Kabul". BBC. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ "New Afghan leadership's 'national reconciliation' policy signals welcome changes". India Today.

- ^ "SOVIET 'COLLAPSE' SHIFTS THE AXIS OF GLOBAL POLITICS – The Washington Post". The Washington Post.

- ^ "The Ghost of Najibullah: Hezb-e Watan announces (another) relaunch – Afghanistan Analysts Network". www.afghanistan-analysts.org. 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Rebels Scorn Afghan Leader's Offer of Elections". Associated Press.

- ^ a b c d Tucker, Spencer (2010). The Encyclopedia of Middle East Wars: The United States in the Persian Gulf, Afghanistan, and Iraq Conflicts. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 874. ISBN 978-1-85109-947-4.

- ^ J. Bruce Amstutz (1986). Afghanistan: The First Five Years of Soviet Occupation. National Defense University. p. 76.; see also Hafizullah Emadi (2005). Culture and Customs of Afghanistan. Greenwood Press. p. 46. ISBN 0-313-33089-1.

- ^ a b Dorronsoro, Gilles (2005). Revolution Unending: Afghanistan, 1979 to the Present. C. Hurst & Co Publishers. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-85065-703-3.

- ^ Weiner, Myron; Banuazizi, Ali (1994). The Politics of Social Transformation in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. Syracuse University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8156-2608-4.

- ^ Kakar, Hassan; Kakar, Mohammed (1997). Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982. University of California Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-520-20893-3.

- ^ Amtstutz, J. Bruce (1994). Afghanistan: The First Five Years of Soviet Occupation. Diane Publishing. p. 266. ISBN 0-7881-1111-6.

- ^ a b c Amtstutz, J. Bruce (1994). Afghanistan: Past and Present. Diane Publishing. p. 152. ISBN 0-7881-1111-6.

- ^ Girardet, Edward (1985). Afghanistan: The Soviet War. Taylor & Francis. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-7099-3802-6.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Kalinovsky, Artemy (2011). A Long Goodbye: The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan. Harvard University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-674-05866-8.

- ^ Kalinovsky, Artemy (2011). A Long Goodbye: The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan. Harvard University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0-674-05866-8.

- ^ Dorronsoro, Gilles (2005). Revolution Unending: Afghanistan, 1979 to the Present. C. Hurst & Co Publishers. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-85065-703-3.

- ^ Kalinovsky, Artemy (2011). A Long Goodbye: The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan. Harvard University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-674-05866-8.

- ^ Kalinovsky, Artemy (2011). A Long Goodbye: The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan. Harvard University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-674-05866-8.

- ^ a b Kalinovsky, Artemy (2011). A Long Goodbye: The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan. Harvard University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-674-05866-8.

- ^ Clements, Frank (2003). Conflict in Afghanistan: a Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-85109-402-8.

- ^ Kalinovsky, Artemy (2011). A Long Goodbye: The Soviet Withdrawal from Afghanistan. Harvard University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-674-05866-8.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Amtstutz, J. Bruce (1994). Afghanistan: Past and Present. DIANE Publishing. p. 153. ISBN 0-7881-1111-6.

- ^ a b c Otto, Jan Michiel (2010). Sharia Incorporated: A Comparative Overview of the Legal Systems of Twelve Muslim Countries in Past and Present. Amsterdam University Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-90-8728-057-4.

- ^ Giustozzi, Antonio (2000). War, Politics and Society in Afghanistan, 1978–1992. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-85065-396-7.

- ^ Giustozzi, Antonio (2000). War, Politics and Society in Afghanistan, 1978–1992. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-1-85065-396-7.

- ^ Regional Surveys of the World: Far East and Australasia 2003. Routledge. 2002. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-85743-133-9.

- ^ Giustozzi, Antonio (2000). War, Politics and Society in Afghanistan, 1978–1992. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-85065-396-7.

- ^ Giustozzi, Antonio (2000). War, Politics and Society in Afghanistan, 1978–1992. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-85065-396-7.

- ^ Giustozzi, Antonio (2000). War, Politics and Society in Afghanistan, 1978–1992. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-85065-396-7.

- ^ Riaz, Ali (2010). Religion and politics in South Asia. Taylor & Francis. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-415-77800-8.

- ^ Yassari, Nadjma (2005). The Sharīʻa in the Constitutions of Afghanistan, Iran, and Egypt: Implications for Private Law. Mohr Siebeck. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-16-148787-3.

- ^ Regional Surveys of the World: Far East and Australasia 2003. Routledge. 2002. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-85743-133-9.

- ^ a b c Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 276. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 277. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 280. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ a b Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 287. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ a b Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 288. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ a b Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 296. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Hiro, Dilip (2002). War Without End: The Rise of Islamist terrorism and Global Response. Routledge. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-415-28802-6.

- ^ Amtstutz, J. Bruce (1994). Afghanistan: Past and Present. DIANE Publishing. p. 151. ISBN 0-7881-1111-6.

- ^ Hilali, A. Z. (2005). US–Pakistan relationship: Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Ashgate Publishing. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-7546-4220-6.

- ^ a b "Explained: Why a top Afghan official visited the grave of ex-President Najibullah". 30 May 2020.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. pp. 296–297. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 297. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 298. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ a b Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Halim Tanwir, Dr. M. (February 2013). AFGHANISTAN: History, Diplomacy and Journalism Volume 1. ISBN 9781479760909.

- ^ "Afghanistan".

- ^ "Murder of a president: How India and the UN mucked up completely in Afghanistan". 30 October 2017.

- ^ Girardet, Edward (2012). Killing the Cranes: A Reporter's Journey through Three Decades of War in Afghanistan. ISBN 9781603583190.

- ^ Regional Surveys of the World: Far East and Australasia 2003. Routledge. 2002. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-85743-133-9.

- ^ "Ex president hanged by Taliban after fall of Kabul". Irish Times. 28 September 1996. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Latifi, Ali M. (22 June 2012). "Executed Afghan president stages 'comeback'". aljazeera.com. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ "All attempts to take Najibullah safely out of Afghanistan fail". Indiatoday.intoday.in. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ "Murder of a president: How India and the UN mucked up completely in Afghanistan". Gz.com. 30 October 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ "Exclusive! How India reached out to the Afghan Mujahideen". Rediff.com. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ Coll, Steve (2004). Page 333 – Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the Cia, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001. Penguin. p. 695. ISBN 9781594200076.

- ^ Braithwaite, Rodric (2007). Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–1989. Indo-European Publishing. pp. 302–303. ISBN 978-1-60444-002-7.

- ^ Rashid, A. (2002). Taliban: Islam, Oil and the New Great Game in Central Asia. Quote on p. 49. Also see footnote 15 on p. 252

- ^ Interview with General Tokhi. Relevant section from 09.40 min. – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4MPzl7DnrTg

- ^ Parry, Robert (7 April 2013). "Hollywood's Dangerous Afghan Illusion". Consortiumnews.com. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d Rashid, Ahmed (2002). Taliban: Islam, Oil and the New Great Game in Central Asia. I.B. Tauris & Company. p. 49. ISBN 978-1845117887.

- ^ "Situation of human rights in Afghanistan" United Nations Resolution 51/108, Article 10. 12 December 1996. Retrieved 15 June 2015 "Endorses the Special Rapporteur's condemnation of the abduction from United Nations premises of the former President of Afghanistan, Mr. Najibullah, and of his brother, and of their subsequent summary execution;"

- ^ Pigott, Peter. Canada in Afghanistan: The War So Far. Toronto: Dundurn Press Ltd, 2007. ISBN 978-1-55002-674-0. p. 54. – via Google Books

- ^ "Researchers Blame Pakistan's ISI for Death of Ex-President Najibullah".

- ^ "فتانه نجیب: د قبر تر جوړېدو مخکې دې د نجیب د مرګ پلټنه وشي". BBC News پښتو (in Pashto). 1 June 2020.

- ^ Parenti, Christian (17 April 2012). "Ideology and Electricity: The Soviet Experience in Afghanistan – The Nation" – via www.thenation.com.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - ^ "Shift Dr. Najibullah's corpse to Kabul: Paktia residents – The Pashtun Times". 30 August 2016.

- ^ Afghan Biographies – Olumi, Noorulhaq Noor ul Haq Olomi Ulumi Archived 23 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Fisher, Earleen (13 July 1991). "Najibullah Retains Control With Power and Pragmatism". AP News. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Najibullah's Family in India, Government Says". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 5 July 2021.

- ^ Morasch, Viktoria (5 February 2017). "Tochter eines Ex-Präsidenten Afghanistans: "Mein Vater sagte: Es ist Krieg"". Die Tageszeitung: Taz.

- ^ Biography Heela Najibullah

- ^ Heela Najibullah: From First Daughter in Afghanistan to Refugee

- ^ "Webber Architects » farewell onai najibullah". Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "From Afghanistan to Australia via Delhi | Gulfnews – Gulf News".

- ^ "Ms Moska Najib : Associated Academics : ... : Sussex Asia Centre : University of Sussex".

- ^ I photograph and remember memories: Mosca Najib

- ^ yourstory.com/2013/05/australias-best-jobs-in-the-world-gets-half-a-mil-entries-afghan-indian-moska-najib-in-the-running

- ^ Agency roles were shown on the first day of Spikes Asia 2014

External links

- Biography of President Najibullah Archived 23 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- 1947 births

- 1996 deaths

- 20th-century heads of state of Afghanistan

- Communist rulers of Afghanistan

- Presidents of Afghanistan

- People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan politicians

- Afghan murder victims

- Castrated people

- Executed Afghan people

- Executed presidents

- People killed by the Taliban

- Ambassadors of Afghanistan to Iran

- Afghan physicians

- People executed by torture

- Assassinated heads of state

- Pashtun people

- People from Kabul

- Habibia High School alumni

- Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

- 1980s in Afghanistan

- 1990s in Afghanistan

- 20th-century executions by Afghanistan

- Muslim socialists

- 20th-century physicians

- Burials in Afghanistan

- Afghan exiles

- Executed communists