Battle of George Square

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

| Battle of George Square | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Red Clydeside and the Revolutions of 1917–1923 | |||

| |||

| Date | 31 January 1919 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Goals |

| ||

| Methods |

| ||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

Decentralized leadership | |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| Many injured; one police constable died later of injuries received | |||

The Battle of George Square was a violent confrontation in Glasgow, Scotland between City of Glasgow Police and striking workers, centred around George Square. The "battle", also known as "Bloody Friday" or "Black Friday", took place on Friday 31 January 1919, shortly after the end of the First World War. During the riot, the Sheriff of Lanarkshire called for military aid, and government troops, supported by six tanks, were moved to key points in the city. The strike leaders were arrested for inciting the riot. Although it is often stated that there were no fatalities, one police constable died several months later from injuries received during the rioting.[1][2]

40-Hour Strike

The end of the First World War saw the United Kingdom demobilise its military and industry from its war footing, reducing employment. This combined with the increasingly worsening domestic fiscal and monetary environment to create the prospect of mass unemployment. The Scottish TUC and Clyde Workers' Committee (CWC) sought to increase the availability of jobs open to demobilised soldiers by reducing the working week from a newly-agreed 47 hours to 40 hours.[3]

The resulting strike began on Monday 27 January, with a meeting of around 3,000 workers held at the St. Andrew's Halls.[4] By 30 January, 40,000 workers from the Clyde's engineering and shipbuilding industries had joined. Sympathy strikes also started among local power station workers and miners from the nearby Lanarkshire and Stirlingshire pits. The rapid growth of the action was credited to flying pickets,[5][failed verification] most of whom were recently discharged servicemen. This was Scotland's most widespread strike since the Radical War of 1820,[6][failed verification] which had followed the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

On 29 January a delegation of strikers met the Lord Provost of Glasgow, and it was agreed that he would send a telegram to the Deputy Prime Minister, Bonar Law, asking the government to intervene. It was agreed that the strikers would return at noon on Friday 31 January to hear the response. After the meeting, the Sheriff of Lanarkshire contacted the government to ask if military aid would be available to him, if needed, should there be any disorder on the Friday.[1]

The telegram and the Sheriff's request prompted the War Cabinet to discuss the 'Strike Situation in Glasgow' on 30 January[7] The meeting was chaired by Bonar Law in the absence of the prime minister, Lloyd George. Winston Churchill, Secretary of State for War and Robert Munro, Secretary of State for Scotland, who were not members of the War Cabinet were in attendance, among others.

At the meeting concern was voiced that, given the concurrent European popular uprisings, the strike had the possibility to spread throughout the country. While it was government policy at the time to not involve itself in labour disputes, the agreed action was justified to ensure there was 'sufficient force'[8] present within the immediate locale of Glasgow to secure the continuation of public order and operation of municipal services.[9] The decision to use the armed forces to provide the requested force, in the absence of a declaration of martial law, required those forces be acting on behalf of a civil authority.[10] On the meeting's close, instructions were sent to Scottish Command informing of the situation and to be prepared to deploy government troops if requested.[7]

Violence between protesters and police

On 31 January, a large number of strikers (contemporary estimates range from 20,000 to 25,000[11]) congregated in George Square. They were awaiting an answer to the telegram the Lord Provost of Glasgow had sent to the Prime Minister on behalf of a delegation of strikers on 29 January, asking the government to intervene.[12]

Accounts differ on what initiated the violence on the day, but police testimony at the following trials records that the police baton charged the striking workers at 12:20.[13]

As the fighting started in George Square, a Clyde Workers' Committee deputation was in the Glasgow City Chambers meeting with the Lord Provost of Glasgow. On hearing the news, CWC leaders David Kirkwood and Emanuel Shinwell left the City Chambers.

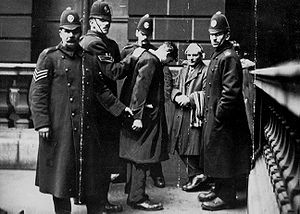

Kirkwood was knocked to the ground by a police baton.[14] Then he, William Gallacher and Shinwell were arrested. They were charged with "instigating and inciting large crowds of persons to form part of a riotous mob".[15][16] Kirkwood was found not guilty at trial after a photograph was submitted to the court, showing him being struck from behind by a policeman, in an apparently unprovoked attack.

After the baton charge, the outnumbered police retreated from George Square. The fighting between the strikers and police, some mounted, spread into the surrounding streets and continued into the night.[17] During the evening Police Constable William McGregor (who had recently returned to the police from the army) was struck on the head by a bottle thrown by rioters in the Saltmarket; he died of his injuries on 1 June 1919.[2]

Military deployment

The events of the day prompted the request for military assistance by the Sheriff of Lanarkshire (Alastair Oswald Morison Mackenzie, 1917-1933) the most senior locally based judge, also known as the Sheriff Principal. The deployment had already begun before the day's meeting of the War Cabinet,[18] which convened at 3pm.[19]

During that meeting Munro, Secretary for Scotland, described the demonstration as "a Bolshevist uprising". It was decided to deploy troops from Scotland and Northern England: troops from the local Maryhill barracks were not deployed because it was feared that men there might have sided with their neighbours.[20] General Sir Charles Harington, the Deputy Chief of the Imperial General Staff informed the meeting that 6 tanks supported by 100 lorries were "going north that evening".[19] It was stated that up to 12,000 troops could be deployed.

It is sometimes suggested that the War Cabinet ordered this deployment, but this is incorrect: the government lacked the authority to deploy troops against British civilians without declaring martial law, which was not declared. The War Cabinet discussed the issue but the military deployment was in response to the request from the Sheriff of Lanarkshire.[18]

The first troops arrived that night,[21] with their numbers increasing over the next few days. The six Medium Mark C tanks, of the Royal Tank Regiment arrived from Bovington on Monday 3 February.[22] Machine gun nests were placed in George Square. The Observer newspaper reported that "The city chambers is like an armed camp.'The quadrangle is full of troops and equipment, including machine guns."[20]

The military arrived after the rioting was over and they played no active role in dispersing the protesters.[18] The troops guarded locations of importance to the civil authorities throughout the period of the strike, which lasted until 12 February. The troops and tanks then remained in Glasgow, and its surrounding areas, until 18 February.[23]

Outcome

Calm returned to the city by the Sunday. Despite the military deployment, there were no fatalities.[20]

The strike ended on 12 February. With the strike over, the strikers gave up their cause for a 40-hour work week and therefore, by default, accepted the previously agreed 47 hours.

Key members involved in the strike were arrested in the immediate aftermath of the events of the 31st. Only two – William Gallacher and Emanuel Shinwell – were convicted, and were sentenced to five months and three months in prison respectively.[24]

Some of those involved claim that this came close to being a successful revolution. Gallacher said "had there been an experienced revolutionary leadership, instead of a march to Glasgow Green there would have been a march to the city's Maryhill Barracks. There we could easily have persuaded the soldiers to come out, and Glasgow would have been in our hands."[25] Most historians now dispute this claim and argue that it was a reformist rather than revolutionary gathering.[25] Gallacher always regretted not having taken a more revolutionary approach to the 40-hour strike and to the events in George Square in 1919, writing afterwards that, "We were carrying on a strike when we ought to have been making a revolution".[26] Emanuel Shinwell, born to a Jewish immigrant family in London, ran in the municipal elections to the Glasgow Corporation following his release from prison.[27]

In the general election of 1922, the second election held after the passage of the Representation of the People Act 1918, Scotland elected 29 Labour MPs. Their number included the 40 Hour Strike organisers and Independent Labour Party members Manny Shinwell and David Kirkwood.[28][29] The General Election of 1923 eventually saw the first Labour government come to power under Ramsay MacDonald. The region's socialist sympathies earned it the epithet of Red Clydeside.[30]

See also

References

- ^ a b Barclay, Gordon (2018). "'Duties in aid of the civil power': the Deployment of the Army to Glasgow, 31 January to 17 February 1919". Journal of Scottish Historical Studies, 38.2, 2018, 261-292. Vol. 38, no. 2. pp. 261–292. doi:10.3366/jshs.2018.0248. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Scottish Police Memorial Trust Roll of Honour". Scottish Police Memorial Trust. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Manifesto of Joint Strike Committee, Glasgow, Feb 1919". Glasgow Digital Library. University of Strathclyde. 31 January 2019.

- ^ "The 40 Hours Strike 1919". Glasgow Digital Library. University of Strathclyde. 31 January 2019.

- ^ "The last reading of the Riot Act". BBC News. BBC Scotland. 30 January 2009.

- ^ Lennon, Holly (15 December 2015). "Looking back: Scotland's political protests". The Scotsman.

- ^ a b "War Cabinet, Minutes of Meeting 522, 30 January 1919". UK National Archives. CAB 23/9/9

- ^ The Glasgow Herald, 7 February 1919

- ^ Pamphlet, Duties in Aid of the Civil Power, "Use of military personnel in aid of civil powers in event of civil disturbances and strikes". UK National Archives. WO 32/18921

- ^ The King's Regulations and Orders for the Army (1914)

- ^ "Debunking more myths around the battle of George Square". HeraldScotland. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ McLean, Iain (1983). The legend of Red Clydeside. Edinburgh: J. Donald. ISBN 9780859765169. OCLC 44884180.

- ^ Evening News, 31 January 1919

- ^ "David Kirkwood on the ground after being struck by police batons, 31 Jan 1919". Glasgow Digital Library. University of Strathclyde. 31 January 2019.

- ^ "Kirkwood and Gallacher arrested during 'Bloody Friday', 31 Jan 1919". Glasgow Digital Library. University of Strathclyde. 31 January 2019.

- ^ "Letter from lawyer of Emanuel Shinwell to defence witnesses in the 40 hours strike trial, 31 Jan 1919". Glasgow Digital Library. University of Strathclyde. 31 January 2019.

- ^ National Records of Scotland file JC 36/31, Trial transcript from the trial of William McCartney etc. Evidence of the Chief Constable

- ^ a b c "Debunking more myths around the battle of George Square". The Herald. 20 April 2018.

- ^ a b CAB 23/9/9, 'War Cabinet, Minutes of Meeting 523, 31 January 1919'

- ^ a b c McKie, Robin (6 January 2019). "100 years on: the day they read the Riot Act as chaos engulfed Glasgow". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Evening News, 3 February 1919

- ^ Aberdeen Daily Journal (later Aberdeen Press & Journal), Tuesday 4 February 1919. "Tanks Reinforce Troops in Glasgow"

- ^ Glasgow Herald, Tuesday 18 February 1919. "Departure of Troops from Glasgow"

- ^ "Petition for the release of CWC leaders, 31 Jan 1919". Glasgow Digital Library. University of Strathclyde. 31 January 2019.

- ^ a b McKie, Robin (6 January 2019). "100 years on: the day they read the Riot Act as chaos engulfed Glasgow". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Gallacher, William (2017) [1936]. Revolt on the Clyde. London: Lawrence & Wishart. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-912064-69-4.

- ^ "Election address of Emanuel Shinwell, Labour candidate for Govan Fairfield ward, 4 Nov 1919". Glasgow Digital Library. University of Strathclyde. 31 January 2019.

- ^ The Times, 17 November 1922

- ^ "David Kirkwood: Biography". Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ^ "Red Clydeside – 20th and 21st centuries". Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

Bibliography

- Red Clydeside

- 1919 riots in the United Kingdom

- History of Glasgow

- Riots and civil disorder in Scotland

- Labour disputes in Scotland

- Aftermath of World War I in the United Kingdom

- Protests in Scotland

- 1919 in Scotland

- 20th-century history of the British Army

- Economy of Glasgow

- January 1919 events

- Revolutions of 1917–1923

- 1910s in Glasgow

- Bonar Law

- Winston Churchill