Pope Manufacturing Company

| |

| Company type | Bicycle and Automobile Manufacturing |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1876 |

| Founder | Albert Augustus Pope |

| Fate | Defunct in 1918 |

| Headquarters | , |

Area served | United States |

| Products | Bicycles Motorcycles Automobiles Automotive parts |

Pope Manufacturing Company was founded by Albert Augustus Pope around 1876 in Boston, Massachusetts, US and incorporated in Hartford, Connecticut in 1877. Manufacturing of bicycles began in 1878 in Hartford at the Weed Sewing Machine Company factory. Pope manufactured bicycles, motorcycles, and automobiles. From 1905 to 1913, Pope gradually consolidated manufacturing to the Westfield Mass plant. The main offices remained in Hartford. It ceased automobile production in 1915 and ceased motorcycle production in 1918. The company subsequently underwent a variety of changes in form, name and product lines through the intervening years. To this day, bicycles continue to be sold under the Columbia brand.

Early years

Pope Manufacturing Company was listed in the 1876 Boston City Directory, located at 54 High Street. In March 1877, the company drafted incorporation documents in Connecticut, naming Albert Pope, Charles Pope, and Edward Pope as shareholders. At the time of incorporation, Albert Pope held 595 shares, his father Charles held 400 shares, and his cousin Edward held five shares.[1] The incorporation documents stated the company's intended business activities, "[to] make, manufacture and sell and licence to others to make, manufacture and sell air pistols and guns, darning machines, amateur lathes, cigarette rollers and other patented articles and to own, sell and deal in patents and patent rights for the manufacture thereof."[1] Pope Manufacturing Company was already selling air pistols and cigarette rolling machines.[2]

Though Pope Manufacturing had filed for incorporation in Connecticut, it continued to base its offices and many of its operations in Boston.[3] Albert and Edward Pope operated a factory at 87 Summer Street in Boston as early as 1874 for the production of hand-held cigarette rolling machines.[4]

Bicycles

Imports and the first Columbias

Albert Pope started advertising imported English bicycles for sale in March 1878. His initial investment in the Pope Manufacturing Company was $3,000 (USD), or worth about $125,000 in the early 21st century. He invested about $4,000 in 1878 to import about fifty English bicycles. In May 1878, he met with George Fairfield, president of Weed Sewing Machine Company. Albert Pope was inquiring about manufacturing his own brand of bicycles, proposing a contract with Weed to build fifty bicycles at its plant in Hartford, Connecticut, on behalf of Pope Manufacturing. Pope had ridden an imported Excelsior Duplex model penny farthing to the meeting, which Fairfield inspected. At that time, sewing machines were selling poorly, so Fairfield accepted the contract.[5]

In September 1878, Weed Sewing Machine Company built the last of the fifty bikes under the first contract. Albert Pope chose the brand name Columbia for the first high-wheelers "produced" by Pope Manufacturing. These first machines, copied from the Excelsior Duplex model, were made from seventy-seven parts that were made in-house, and only the rubber tires purchased from a supplier. Pope Manufacturing sold all its bicycles from the first production run. In 1879, production and sales were around 1,000, the last year of the Excelsior Duplex copies.[6]

George Herbert Day worked as a clerk at Weed Sewing Machine Company when the company started producing high-wheelers for Pope Manufacturing. In early 1879, Day was promoted to corporate secretary. One historian characterized Day as "Albert Pope's right-hand man in Hartford between 1878 and 1899."[7] Albert's cousin Edward started work as the Pope Manufacturing bookkeeper in 1880.[8]

George Bidwell, an independent salesman from Buffalo, New York, purchased an imported Excelsior Duplex high-wheeler from Pope. Learning in a correspondence from Pope that he would be producing his own bicycle, Bidwell started taking orders for the Columbias. Bidwell sold seventy-five of the machines, holding down payments for each. Pope could only deliver about twenty-five. Shortly later, Pope hired Bidwell as Superintendent of Agencies, a job sending Bidwell on the road to teach sale agents the art of promotion. Bidwell taught agents how to promote the sport through riding halls and schools.[9]

Redesigning the ordinaries

In 1880, George Fairfield introduced design changes and proposed two ordinary Columbia models. Each weighed about forty-one pounds and featured an improved seat-spring and an improved head-adjustment. The Standard Columbia with a forty-eight inch wheel was introduced in 1880 priced at $87.50. The Special Columbia offered "a closed Stanley-style head," a "built-in" ball-bearing assembly, and full nickel-plating for $132.50.[10]

In 1881, Pope gained controlling interest of Weed, catalyzing a fifteen-fold increase in Weed's stock price. George Day was promoted to president of Weed.[11]

After the introduction of the high wheeler, Pope bought Pierre Lallement's original patent for the bicycle, and aggressively bought all other bicycle patents he could find, amassing a fortune by restricting the types of bicycles other American manufacturers could make and charging them royalties.[12] He used the latest technologies in his bicycles—inventions such as ball bearings in all moving parts, and hollow steel tubes for the frame, and he spent a great deal of money promoting bicycle clubs, journals, and races.[12]

Safety bicycles

Ordinaries (high-wheelers or penny farthings) were driven by cranks and pedals attached directly to an oversized front wheel. The rider was seated over the wheel, just aft of the wheel hub. Many mishaps included the projection of the rider head-first over the handle bars: an event occurring with enough frequency to earn the name, header. Several manufacturers created safety models, which denoted a low-mount bicycle. Motive force came from cranks applied to a sprocket and chain creating an indirect drive to one of the wheels. The first commercially viable model was John Kemp Starley's Rover, drawing interest starting in 1885. The early Rover featured a complicated indirect steering system, but Starley replaced it with a direct steering system consisting of a single curved bar attached to the head. In 1886, after seeing some Rovers and touring a Rover-factory, Alfred Pope claimed that the safety bicycle was nothing more than a fad, and made no plans at that time to produce his own version. George Bidwell, by this time an independent agent again, recommended the safety after trying the mount in 1886.[13] He urged Pope to design its own safety bicycle while predicting "the old high wheel was doomed."[14]

However, Pope did offer a safety ordinary model in 1886. This design retained the high-mount and oversized front wheel, but incorporated a chain drive to the front wheel, allowing the seating position and cranks to be positioned further back. Despite the new Columbia offering, Bidwell claimed that he never ordered another high-wheeler after trying the Rover. By 1888, Pope had reversed course and produced its own safety, the Veloce. It weighed 51 pounds (23 kg), or 15 pounds (6.8 kg) heavier than its ordinary. In 1889, ordinaries only accounted for twenty percent of sales, dropping to ten percent of sales the next year. Once Pope offered the Veloce for sale, the company sold only 3,000 ordinaries through 1891.[15]

Pope Manufacturing was an innovator in the use of stamping for the production of metal parts. Until 1896, the company was the leading US producer of bicycles.

Hartford Cycle Company

At a time when Pope charged $125 for a Columbia, Overman Wheel Company was marketing a bicycle for wage workers, who might earn $1 per day. Instead of reducing cost and price on the Columbias, Pope decided to produce a separate line to compete with Overman.[16] Around 1890, Pope started another manufacturer, Hartford Cycle Company in order to create a new line with a mid-price niche. He installed his cousin George to run the plant. He transferred David J. Post from Weed to serve as secretary for Hartford. MIT-graduate Harry Melville Pope, Albert's nephew, was Hartford's superintendent.[16][9] Pope Manufacturing subsumed Hartford Cycle Company in 1895.[17]

Steel tubing

Ordinaries had used a heavy pipe, but the safeties used twenty-seven feet of tubing: solid round bar would weigh down the machine. Safeties required thin, high-strength steel tubing. Almost all the Pope manufacturing facilities were located in Hartford in an area previously known for gun-making. Like bicycles, rifle barrels required thin, high-strength tubes, so the skills and processes of rifle manufacturing were related to the manufacturing of steel tubing for safety bicycles. Importing tubes cost an American manufacturer a forty-five percent import tariff, thus creating a financial incentive for domestic production. The sudden popularity of safety bicycles in the United States created a shortage of tubing supply for manufacturers, both in Europe and the United States. Albert Pope had invested in Shelby Steel Tubing, even while building two steel tubing factories in Hartford, owned by Pope Manufacturing. One was an experimental facility, and the other for commercial production.[18]

Two Pope employees, Henry Souther and Harold Hayden Eames, collaborated on a new process for producing bicycle tubing. Souther had been experimenting with stress tolerances of different metals, and concluded that steel with five-percent nickel alloy would be ideal for bicycle tubing. At the time, this metal was only available in sheet form. Eames devised a process for converting metal sheets into billets, which could be cold-drawn through dies with methods and equipment already in use at the Pope tube works. The new tubing was stronger and more resistant to dents than the carbon-steel that was commonly used.[19]

Hartford Rubber Works

Pope Manufacturing acquired the Hartford Rubber Works in 1892 as part of a vertical integration strategy. Founded by John Gray in 1885, Hartford Rubber Works imported raw material from Sumatra and produced solid tires. Later the factory produced cushion and pneumatic tires.[20][17]

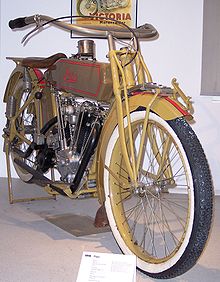

Motorcycles

Pope began manufacturing motorized bicycles in 1902 and continued with motorcycles until 1918.[21]

Mopeds (late 20th century)

Columbia mopeds were the first mopeds ever assembled in the United States, even though the motor and some parts were outsourced. The tubular frames, seats, fenders, wheels, hubs, brakes, front fork assembly, headlight, and wiring harnesses were made in the United States.[22]

The majority of Columbia mopeds were powered with a 47cc Sachs 505/1A, though some were powered by a Solo motor. Even though the Sachs 505/1A motor is designed for rear coaster-brakes, Columbia chose to use a Magura hand lever and cable for the rear brake.

- There are two models that are the most abundant frame types for Columbia, both of which went by the same name of Columbia Commuter. The pressed steel frame was Sachs-powered only, while the tube frame model had either the Sachs or the Solo motor.

- The top-tank Columbia Medallion, also known as the Western Flyer, is a unique design for Columbia mopeds. Essentially, the frame of the bike is identical to the tube frame Commuter, but it has a plastic gas tank that reaches from the seat to the steering column.

- The "Western Flyer" name came on all frame types, and is not specific to any model. These bikes were sold under the name "Western Flyer" instead of Columbia.

In the late 1980s, Columbia sold the rights and design of their mopeds to a company, KKM Enterprises, Inc. that produced identical mopeds under the name Mopet into the mid-1990s. This company produced the tubular frames, long seats, fenders, wheels, hubs, brakes, front fork assembly, headlight, and wiring harnesses in the United States.

Models:

- Columbia "Commuter"

- Columbia "Imperial"

- Columbia "Medallion 2271"

- Columbia "Medallion 2281"

- Columbia "Model 57062"

- Columbia "Model 2251"

- Columbia "Model 2241"

- Columbia "Motrek"

- Columbia "Western Flyer" (not to be confused with the Western Auto company's "Western Flyer"

Automobiles

In 1897, Pope Manufacturing began production of an electric automobile.[23] By 1899, the company had produced over 500 vehicles. Hiram Percy Maxim was head engineer of the Motor Vehicle Department. The Electric Vehicle division was spun off that year as the independent company Columbia Automobile Company but it was acquired by the Electric Vehicle Company by the end of year.[23]

Pope tried to re-enter the automobile manufacturing market in 1901 by acquiring a number of small firms, but the process was expensive and competition in the industry was heating up.

Between the years 1903 and 1915, the company operated a number of automobile companies including Pope-Hartford (1903–1914), Pope-Robinson, Pope-Toledo (1903–1909), Pope-Tribune (1904–1907) and Pope-Waverley.[24]

Between 1906 and 1907, Pope's Toledo manufacturing plant was subject to the automotive industry's first labor strike, which ended in success for the striking Pope workers.[25]

Pope declared bankruptcy in 1907[23] and died in August 1909.[26]

Bankruptcy and reorganizations

In 1914, the main offices of Pope were moved to Westfield, Massachusetts. However, in 1915, the Pope Manufacturing Company filed for bankruptcy. In 1916 Pope was reorganized and renamed The Westfield Manufacturing Company, with catalogs stating they were the “successors to The Pope Manufacturing Company.” In 1933, Westfield Manufacturing became a subsidiary of The Torrington Company of Torrington, Connecticut. In December 1960 an independent corporation was formed and in 1961 was renamed Columbia Manufacturing Company. In 1967, Columbia Manufacturing Company merged with MTD, but ended up filing for bankruptcy in 1987. The following year saw Columbia purchased by some of the local management and reorganized as Columbia Manufacturing, Inc., and no longer part of MTD. Bicycle production continued in a limited capacity, but was negligible compared to the business of importing and selling foreign bicycles. As of the 2010s, Columbia-branded bicycles are marketed by Columbia Bicycles, a subsidiary of Ballard Pacific.

Gallery

-

1882 advertisement from Lippincott's Magazine

-

1883 advertisement for the Boston market

-

1886 advertisement for Columbia Bicycles

-

1895 advertisement for Columbia Bicycles

-

1912 catalog for Columbia Bicycles

-

1912 advertisement for Columbia Bicycles

-

1914 advertisement for Pope-Hartford automobiles

-

Pope Manufacturing Company Columbia bikes

See also

References

- ^ a b Epperson, Bruce (2010). Peddling Bicycles to America: the rise of an industry. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company. p. 22.

- ^ Goddard, Stephen B. (2000). Col. Pope & his American Dream Machines. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company. p. 63.

- ^ Epperson (2010), pp. 22–23.

- ^ Epperson (2010), p. 21.

- ^ Epperson (2010), pp. 29–31.

- ^ Epperson (2010), p. 31.

- ^ Epperson (2010), pp. 31–33.

- ^ Goddard (2000), p. 71.

- ^ a b Epperson (2010), p. 65.

- ^ Epperson (2010), pp. 32–33.

- ^ Goddard (2000), p. 70.

- ^ a b Herlihy, David V. (2004). Bicycle, The History. Yale University Press. pp. 184–192. ISBN 0-300-10418-9.

- ^ Herlihy (2004), pp. 235–241.

- ^ Epperson (2010), p. 84.

- ^ Epperson (2010), pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Goddard (2000), pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b Goddard (2000), pp. 237–240.

- ^ Epperson (2010), pp. 109–111.

- ^ Epperson (2010), pp.112–116.

- ^ Goddard (2000), p. 209.

- ^ "Pope Motor Bikes & Motorcycles". MrColumbia. Archived from the original on 2012-02-11. Retrieved 2012-01-16.

- ^ "Columbia - MopedWiki". MopedArmy. Retrieved 2013-05-24.

- ^ a b c David Corrigan. "The Columbia Cars Are Born". Hog River Journal - Exploring CT History. Retrieved 2012-01-16.

- ^ "American Automobiles - Manufacturers". Farber and Associates, LLC - 2011. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ^ Philip S. Foner (1965). History of the Labor Movement in the United States Vol, 4. p. 386.

- ^

Daniel Vaughan (Aug 2005). "1911 Pope-Hartford Model W news, pictures, and information". Conceptcarz.com.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help)

Further reading

- Bruce Epperson. Failed Colossus: Strategic Error at the Pope Manufacturing Company, 1878–1900." Technology and Culture, Vol. 41, No. 2 (Apr., 2000), pp. 300–320.

- David A. Hounshell. From the American system to mass production, 1800–1932. Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1984

- "Pope Manufacturing Company." Moses King, ed. King's handbook of New York city: an outline history and description of the American metropolis. 1892

- Rae, John Bell (1959). American Automobile Manufacturers: The First Forty Years. Philadelphia: Chilton Company – via Hathi Trust.

- "Bicycle-Making: Where and How Bicycles are Made." Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly v.12 no.5, November 1881.

- "The Progress of a great industry." Outing (Advertising Supplement), v.19, no.6, 1892

- "Pope Bicycle building burned; only the walls remain of the handsome Boston headquarters of the Columbia Wheel." New York Times, March 13, 1896

External links

Media related to Pope Manufacturing Company at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pope Manufacturing Company at Wikimedia Commons

- Companies based in Hampden County, Massachusetts

- Companies established in 1876

- Cycle manufacturers of the United States

- Defunct motor vehicle manufacturers of the United States

- History of cycling in Massachusetts

- Manufacturing companies based in Hartford, Connecticut

- 1876 establishments in Massachusetts

- Defunct manufacturing companies based in Massachusetts

- Defunct manufacturing companies based in Connecticut