Royal Flying Corps

| Royal Flying Corps | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 13 April 1912–1 April 1918 |

| Disbanded | merged with RNAS to become Royal Air Force (RAF), 1918 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | King George V |

| Branch | |

| Size | 3,300 aircraft (1918) |

| Motto(s) | Template:Lang-la "Through Adversity to the Stars" |

| Wars | First World War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Sir David Henderson Hugh Trenchard |

| Insignia | |

| Roundel |  |

| Flag |  |

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was the air arm of the British Army before and during the First World War until it merged with the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force. During the early part of the war, the RFC supported the British Army by artillery co-operation and photographic reconnaissance. This work gradually led RFC pilots into aerial battles with German pilots and later in the war included the strafing of enemy infantry and emplacements, the bombing of German military airfields and later the strategic bombing of German industrial and transport facilities.

At the start of World War I the RFC, commanded by Brigadier-General Sir David Henderson, consisted of five squadrons – one observation balloon squadron (RFC No 1 Squadron) and four aeroplane squadrons. These were first used for aerial spotting on 13 September 1914 but only became efficient when they perfected the use of wireless communication at Aubers Ridge on 9 May 1915. Aerial photography was attempted during 1914, but again only became effective the next year. By 1918, photographic images could be taken from 15,000 feet and were interpreted by over 3,000 personnel. Parachutes were not available to pilots of heavier-than-air craft in the RFC – nor were they used by the RAF during the First World War – although the Calthrop Guardian Angel parachute (1916 model) was officially adopted just as the war ended. By this time parachutes had been used by balloonists for three years.[1][verification needed][2]

On 17 August 1917, South African General Jan Smuts presented a report to the War Council on the future of air power. Because of its potential for the 'devastation of enemy lands and the destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale', he recommended a new air service be formed that would be on a level with the Army and Royal Navy. The formation of the new service would also make the under-used men and machines of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) available for action on the Western Front and end the inter-service rivalries that at times had adversely affected aircraft procurement. On 1 April 1918, the RFC and the RNAS were amalgamated to form a new service, the Royal Air Force (RAF), under the control of the new Air Ministry. After starting in 1914 with some 2,073 personnel, by the start of 1919 the RAF had 4,000 combat aircraft and 114,000 personnel in some 150 squadrons.

Origin and early history

With the growing recognition of the potential for aircraft as a cost-effective method of reconnaissance and artillery observation, the Committee of Imperial Defence established a sub-committee to examine the question of military aviation in November 1911. On 28 February 1912 the sub-committee reported its findings which recommended that a flying corps be formed and that it consist of a naval wing, a military wing, a central flying school and an aircraft factory. The recommendations of the committee were accepted and on 13 April 1912 King George V signed a royal warrant establishing the Royal Flying Corps. The Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers became the Military Wing of the Royal Flying Corps a month later on 13 May.

The Flying Corps' initial allowed strength was 133 officers, and by the end of that year it had 12 manned balloons and 36 aeroplanes. The RFC originally came under the responsibility of Brigadier-General Henderson, the Director of Military Training, and had separate branches for the Army and the Navy. Major Sykes commanded the Military Wing[3] and Commander C R Samson commanded the Naval Wing.[4] The Royal Navy however, with different priorities to that of the Army and wishing to retain greater control over its aircraft, formally separated its branch and renamed it the Royal Naval Air Service on 1 July 1914, although a combined central flying school was retained.

The RFC's motto was Per ardua ad astra ("Through adversity to the stars"). This remains the motto of the Royal Air Force (RAF) and other Commonwealth air forces.

The RFC's first fatal crash was on 5 July 1912 near Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain; Captain Eustace B. Loraine and his observer, Staff Sergeant R.H.V. Wilson, flying from Larkhill Aerodrome, were killed. An order was issued after the crash stating "Flying will continue this evening as usual", thus beginning a tradition.

In August 1912 RFC Lieutenant Wilfred Parke RN became the first aviator to be observed to recover from an accidental spin when the Avro G cabin biplane, with which he had just broken a world endurance record, entered a spin at 700 feet above ground level at Larkhill. Four months later on 11 December 1912 Parke was killed when the Handley Page monoplane in which he was flying from Hendon to Oxford crashed.

Ranks in the RFC

| RFC Ranks, Military Wing (13 April 1912)[5] | |

|---|---|

| Rank | Appointments |

| Major-General [1917] | Division Commander |

| Brigadier-General [1915] | Brigade Commander |

| Lieutenant-Colonel [1914] | Wing Commander |

| Major | Squadron Commander |

| Captain | Flight Commander, Recording Officer, Equipment Officer, Transport Officer |

| Lieutenant | Pilot, Observer, Recording Officer, Armament Officer, Equipment Officer, Wireless Officer |

| 2nd Lieutenant | Pilot-in-Training, Pilot; Observer-in-Training, Observer |

| Cadet | Pilot in Training; Observer in Training |

| Warrant Officer I [1915] | Sergeant Major |

| Warrant Officer II [1915] | Quartermaster Sergeant |

| Flight Sergeant | Chief Mechanic |

| Sergeant | Armourer, Fitter, Rigger, Gear Mechanic |

| Corporal | Fitter, Rigger |

| Air Mechanic 1st Class | Armourer, Acetylene Welder, Blacksmith, Coppersmith, Tinsmith, Engine Fitter, Gear Mechanic, Aircraft Rigger, Electrician, Magneto-Repairer, Fitter, Machinist, Sailmaker |

| (Lance Corporal) | |

| Air Mechanic 2nd Class | Armourer, Acetylene Welder, Blacksmith, Coppersmith, Tinsmith, Engine Fitter, Gear Mechanic, Aircraft Rigger, Electrician, Magneto-Repairer, Fitter, Machinist, Sailmaker |

| Private 1st Class | Driver |

| Air Mechanic 3rd Class | Armourer, Acetylene Welder, Blacksmith, Coppersmith, Tinsmith, Engine Fitter, Gear Mechanic, Aircraft Rigger, Electrician, Magneto-Repairer, Fitter, Machinist, Sailmaker |

| Private 2nd Class | Driver |

| Rank group | General / flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(1912–April 1918) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lieutenant-General | Major-General | Brigadier-General | Colonel | Lieutenant Colonel | Major | Captain | Lieutenant | 2nd lieutenant | Cadet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(1912–April 1918) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No insignia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Warrant Officer Class I | Warrant Officer Class II | Quartermaster sergeant | Flight sergeant | Sergeant | Corporal | Air Mechanic 1st Class | Air Mechanic 2nd Class | Air Mechanic 3rd Class | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Aircraft

Aircraft used during the war by the RFC included:

- Airco DH 2, DH 4, DH 5, DH 6, and DH 9

- Armstrong-Whitworth F.K.8

- Avro 504

- Bristol's Bristol Scout single-seat fighter, F2A and F2B Fighter two-seaters

- Handley Page O/400

- Martinsyde G.100

- Morane-Saulnier Bullet Biplane Parasol

- Nieuport Scout 17, 24, 27

- Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2a, B.E.2b, B.E.2c, B.E.2e, B.E.12, F.E.2b, F.E.8, R.E.8, S.E.5a

- Sopwith Aviation Company 1½ Strutter, Pup, Triplane, Camel, Snipe, Dolphin

- SPAD S.VII

- Vickers FB5

Structure and growth

On its inception in 1912 the Royal Flying Corps consisted of a Military and a Naval Wing, with the Military Wing consisting of three squadrons each commanded by a major. The Naval Wing, with fewer pilots and aircraft than the Military Wing, did not organise itself into squadrons until 1914; it separated from the RFC that same year. By November 1914 the Royal Flying Corps, even taking the loss of the Naval Wing into account, had expanded sufficiently to warrant the creation of wings consisting of two or more squadrons. These wings were commanded by lieutenant-colonels. In October 1915 the Corps had undergone further expansion which justified the creation of brigades, each commanded by a brigadier-general. Further expansion led to the creation of divisions, with the Training Division being established in August 1917 and RFC Middle East being raised to divisional status in December 1917. Additionally, although the Royal Flying Corps in France was never titled as a division, by March 1916 it comprised several brigades and its commander (Trenchard) had received a promotion to major-general, giving it in effect divisional status. Finally, the air raids on London and the south-east of England led to the creation of the London Air Defence Area in August 1917[6] under the command of Ashmore who was promoted to major-general.

Squadrons

Two of the first three RFC squadrons were formed from the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers: No. 1 Company (a balloon company) becoming No. 1 Squadron, RFC, and No. 2 Company (a 'heavier-than-air' company) becoming No. 3 Squadron, RFC. A second heavier-than-air squadron, No. 2 Squadron, RFC, was also formed on the same day.

No. 4 Squadron, RFC was formed from No. 2 Sqn in August 1912, and No. 5 Squadron, RFC from No. 3 Sqn in July 1913.

By the end of March 1918, the Royal Flying Corps comprised some 150 squadrons.

The composition of an RFC squadron varied depending on its designated role, although the commanding officer was usually a major (in a largely non-operational role), with the squadron 'flights' (annotated A, B, C etc.) the basic tactical and operational unit, each commanded by a captain. A 'recording officer' (of captain/lieutenant rank) would act as intelligence officer and adjutant, commanding two or three NCOs and ten other ranks in the administration section of the squadron. Each flight contained on average between six and ten pilots (and a corresponding number of observers, if applicable) with a senior sergeant and thirty-six other ranks (as fitters, riggers, metalsmiths, armourers, etc.). The average squadron also had on complement an equipment officer, armaments officer (each with five other ranks) and a transport officer, in charge of twenty-two other ranks. The squadron transport establishment typically included one car, five light tenders, seven heavy tenders, two repair lorries, eight motorcycles and eight trailers.[7]

Wings

Wings in the Royal Flying Corps consisted of a number of squadrons.

When the Royal Flying Corps was established it was intended to be a joint service. Owing to the rivalry between the British Army and Royal Navy, new terminology was thought necessary in order to avoid marking the Corps out as having a particularly Army or Navy ethos. Accordingly, the Corps was originally split into two wings: a Military Wing (i.e. an army wing) and a Naval Wing. By 1914, the Naval Wing had become the Royal Naval Air Service, having gained its independence from the Royal Flying Corps.

By November 1914 the Flying Corps had significantly expanded and it was felt necessary to create organizational units which would control collections of squadrons; the term "wing" was reused for these new organizational units.

The Military Wing was abolished and its units based in Great Britain were regrouped as the Administrative Wing.[8] The RFC squadrons in France were grouped under the newly established 1st Wing and the 2nd Wing. The 1st Wing was assigned to the support of the 1st Army whilst the 2nd Wing supported the 2nd Army.

As the Flying Corps grew, so did the number of wings. The 3rd Wing was established on 1 March 1915 and on 15 April the 5th Wing came into existence. By August that year the 6th Wing had been created and in November 1915 a 7th Wing and 8th Wing had also been stood up. Additional wings continued to be created throughout World War I in line with the incessant demands for air units. The last RFC wing to be created was the 54th Wing in March 1918, just prior to the creation of the RAF.[9]

Following the creation of brigades, wings took on specialised functions. Corps wings undertook artillery observation and ground liaison duties, with one squadron detached to each army corps. Army wings were responsible for air superiority, bombing and strategic reconnaissance. United Kingdom based forces were organised into home defence and training wings. By March 1918, wings controlled as many as nine squadrons.[citation needed]

Brigades

Following Sir David Henderson's return from France to the War Office in August 1915, he submitted a scheme to the Army Council which was intended to expand the command structure of the Flying Corps. The Corps' wings would be grouped in pairs to form brigades and the commander of each brigade would hold the temporary rank of brigadier-general. The scheme met with Lord Kitchener's approval and although some staff officers opposed it, the scheme was adopted.[10]

In the field, most brigades were assigned to the army. Initially a brigade consisted of an army wing and corps wing; beginning in November 1916 a balloon wing was added to control the observation balloon companies. Logistics support was provided by an army aircraft park, aircraft ammunition column and reserve lorry park.

Stations

All operating locations were officially called "Royal Flying Corps Station name". A typical Squadron may have been based at four Stations – an Aerodrome for the HQ, and three Landing Grounds, one per each flight. Stations tended to be named after the local railway station, to simplify the administration of rail travel warrants.

Typically a training airfield consisted of a 2,000 feet (610 m) grass square. There were three pairs plus one single hangar, constructed of wood or brick, 180 feet (55 m) x 100 feet (30 m) in size. There were up to 12 canvas Bessonneau hangars as the aircraft, constructed from wood, wire and fabric, were liable to weather damage. Other airfield buildings were typically wooden or Nissen huts.

Landing Grounds were often L-shaped, usually arrived at by removing a hedge boundary between two fields, and thereby allowing landing runs in two directions of 400–500 metres (1,300–1,600 ft). Typically they would be manned by only two or three airmen, whose job was to guard the fuel stores and assist any aircraft which had occasion to land. Accommodation for airmen and pilots was often in tents, especially on the Western Front. Officers would be billeted to local country houses,[11] or commandeered châteaux when posted abroad, if suitable accommodation had not been built on the Station.

Landing Grounds were categorised according to their lighting and day or night capabilities:

- First Class Landing Ground – Several buildings, hangars and accommodation.

- Second Class Landing Ground – a permanent hangar, and a few huts.

- Third Class Landing Ground – a temporary Bessonneau hangar

- Emergency (or Relief) Landing Ground – often just a field, activated by telephone call to the farmer, requesting he move any grazing animals out.

- Night Landing Grounds would be lit around the perimeter with gas lights and might have a flarepath laid out in nearby fields.

Stations that were heavily used or militarily important grew by compulsorily purchasing extra land, changing designations as necessary. Aerodromes would often grow into sprawling sites, due to the building of headquarters/administration offices, mess buildings, fuel and weapon stores, wireless huts and other support structures as well as the aircraft hangarage and repair facilities. Narborough and Marham both started off as Night Landing Grounds a few miles apart. One was an RNAS Station, the other RFC. Narborough grew to be the largest aerodrome in Britain at 908 acres (367 ha) with 30 acres (12 ha) of buildings including seven large hangars, seven motorised transport (MT) garages, five workshops, two coal yards, two Sergeants' Messes, three dope sheds and a guardhouse. Marham was 80 acres (32 ha). Both these Stations are now lost beneath the present RAF Marham. Similarly, Stations at Easton-on-the-Hill and Stamford merged into modern day RAF Wittering although they are in different counties.

Canada

The Royal Flying Corps Canada was established by the RFC in 1917 to train aircrew in Canada. Air Stations were established in southern Ontario at the following locations:

- Camp Borden 1917–1918

- Armour Heights Field 1917–1918 (pilot training, School of Special Flying to train instructors)

- Leaside Aerodrome 1917–1918 (Artillery Cooperation School)

- Long Branch Aerodrome 1917–1918

- Curtiss School of Aviation (flying-boat station with temporary wooden hangar on the beach at Hanlan's Point on Toronto Island 1915–1918; main school, airstrip and metal hangar facilities at Long Branch)

- Camp Rathbun, Deseronto 1917–1918 (pilot training)

- Camp Mohawk (now Tyendinaga (Mohawk) Airport) 1917–1918 – located at the Tyendinaga Indian Reserve (now Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory) near Belleville 1917–1918 (pilot training)

- Hamilton (Armament School) 1917–1918

- Beamsville Camp (School of Aerial Fighting) 1917–1918 – located at 4222 Saan Road in Beamsville, Ontario; hangar remains and property now used by Global Horticultural Incorporated

Other locations

- St-Omer, France 1914–1918 (headquarters) – now Saint-Omer-Wizernes Airport and site of British Air Services Memorial

- Ismailia, Egypt (training – No. 57 TS, 32 (Training) Wing HQ) – now Al Ismailiyah Air Base

- Aboukir, Egypt 1916–1918 (training – No. 22 TS & No. 23 TS, 20 (Training) Wing HQ)

- Abu Sueir, Egypt 1917–1918 (training – No. 57 TS & No. 195 TS) – now Abu Suwayr Air Base, also used by RAF during World War II

- El Ferdan, Egypt (training – No. 17 TDS)

- El Rimal, Egypt 1917–1918 (training – No. 19 TDS) – later as RAF El Amiriya and now abandoned (after World War II)

- Camp Taliaferro, North Texas, USA 1917–1918 (training) – sites now either residential development or commercial/industrial parks

First World War

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

The RFC was also responsible for the manning and operation of observation balloons on the Western front. When the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) arrived in France in August 1914, it had no observation balloons and it was not until April 1915 that the first balloon company was on strength, albeit on loan from the French Aérostiers. The first British unit arrived 8 May 1915, and commenced operations during the Battle of Aubers Ridge. Operations from balloons thereafter continued throughout the war. Highly hazardous in operation, a balloon could only be expected to last a fortnight before damage or destruction. Results were also highly dependent on the expertise of the observer and was subject to the weather conditions. To keep the balloon out of the range of artillery fire, it was necessary to locate the balloons some distance away from the front line or area of military operations. However, the stable platform offered by a kite-balloon made it more suitable for the cameras of the day than an aircraft.

For the first half of the war, as with the land armies deployed, the French air force vastly outnumbered the RFC, and accordingly did more of the fighting. Despite the primitive aircraft, aggressive leadership by RFC commander Hugh Trenchard and the adoption of a continually offensive stance operationally in efforts to pin the enemy back led to many brave fighting exploits and high casualties – over 700 in 1916, the rate worsening thereafter, until the RFC's nadir in April 1917 which was dubbed 'Bloody April'.

This aggressive, if costly, doctrine did however provide the Army General Staff with vital and up-to-date intelligence on German positions and numbers through continual photographic and observational reconnaissance throughout the war.

1914–15: Initial actions with the British Expeditionary Force

At the start of the war, numbers 2, 3, 4 and 5 Squadrons were equipped with aeroplanes. No. 1 Squadron had been equipped with balloons but all these were transferred to the Naval Wing in 1913; thereafter No. 1 Squadron reorganised itself as an 'aircraft park' for the British Expeditionary Force. The RFC's first casualties were before the Corps even arrived in France: Lt Robert R. Skene and Air Mechanic Ray Barlow were killed on 12 August 1914 when their (probably overloaded) plane crashed at Netheravon on the way to rendezvous with the rest of the RFC near Dover.[12] Skene had been the first Englishman to perform a loop in an aeroplane.

On 13 August 1914, 2, 3, and 4 squadrons, comprising 60 machines, departed from Dover for the British Expeditionary Force in France and 5 Squadron joined them a few days later. The aircraft took a route across the English Channel from Dover to Boulogne, then followed the French coast to the Bay of the Somme and followed the river to Amiens. When the BEF moved forward to Maubeuge the RFC accompanied them. On 19 August the Corps undertook its first action of the war, with two of its aircraft performing aerial reconnaissance. The mission was not a great success; to save weight each aircraft carried a pilot only instead of the usual pilot and observer. Because of this, and poor weather, both of the pilots lost their way and only one was able to complete his task.

On 22 August 1914, the first British aircraft was lost to German fire. The crew – pilot Second Lieutenant Vincent Waterfall and observer Lt. Charles George Gordon Bayly, of 5 Squadron – flying an Avro 504 over Belgium, were killed by infantry fire.[13][14] Also on 22 August 1914, Captain L E O Charlton (observer) and his pilot, Lieutenant Vivian Hugh Nicholas Wadham, made the crucial observation of the 1st German Army's approach towards the flank of the British Expeditionary Force. This allowed the BEF Commander-in-Chief Field Marshal Sir John French to realign his front and save his army around Mons.

Next day, the RFC found itself fighting in the Battle of Mons and two days after that, gained its first air victory. On 25 August, Lt C. W. Wilson and Lt C. E. C. Rabagliati forced down a German Etrich Taube, which had approached their aerodrome while they were refuelling their Avro 504. Another RFC machine landed nearby and the RFC observer chased the German pilot into nearby woods. After the Great Retreat from Mons, the Corps fell back to the Marne where in September, the RFC again proved its value by identifying von Kluck's First Army's left wheel against the exposed French flank. This information was significant as the First Army's manoeuvre allowed French forces to make an effective counter-attack at the Battle of the Marne.

Sir John French's (the British Expeditionary Force commander) first official dispatch on 7 September included the following: "I wish particularly to bring to your Lordships' notice the admirable work done by the Royal Flying Corps under Sir David Henderson. Their skill, energy, and perseverance has been beyond all praise. They have furnished me with most complete and accurate information, which has been of incalculable value in the conduct of operations. Fired at constantly by friend and foe, and not hesitating to fly in every kind of weather, they have remained undaunted throughout. Further, by actually fighting in the air, they have succeeded in destroying five of the enemy's machines."

Markings

Early in the war RFC aircraft were not systematically marked with any national insignia. At a squadron level, Union Flag markings in various styles were often painted on the wings (and sometimes the fuselage sides and/or rudder). However, there was a danger of the large red St George's Cross being mistaken for the German Eisernes Kreuz (iron cross) marking, and so of RFC aircraft being fired upon by friendly ground forces. By late 1915, therefore, the RFC had adopted a modified version of the French cockade (or roundel) marking, with the colours reversed (the blue circle outermost). In contrast to usual French practice, the roundel was applied to the fuselage sides as well as the wings. To minimise the likelihood of "friendly" attack, the rudders of RFC aircraft were painted to match the French, with the blue, white and red stripes – going from the forward (rudder hingeline) to aft (trailing edge) – of the French tricolour. Later in the war, a "night roundel" was adopted for night flying aircraft (especially Handley Page O/400 heavy bombers), which omitted the conspicuous white circle of the "day" marking.

Roles and responsibilities

Wireless telegraphy

Later in September, 1914, during the First Battle of the Aisne, the RFC made use of wireless telegraphy to assist with artillery targeting and took aerial photographs for the first time.[15]

Photo-reconnaissance

From 16,000 feet a photographic plate could cover some 2 by 3 miles (3.2 km × 4.8 km) of front line in sharp detail. In 1915 Lieutenant-Colonel JTC Moore-Brabrazon designed the first practical aerial camera. These semi-automatic cameras became a high priority for the Corps and photo-reconnaissance aircraft were soon operational in numbers with the RFC. The camera was usually fixed to the side of the fuselage, or operated through a hole in the floor. The increasing need for surveys of the western front and its approaches, made extensive aerial photography essential. Aerial photographs were exclusively used in compiling the British Army's highly detailed 1:10,000 scale maps introduced in mid-1915. Such were advances in aerial photography that the entire Somme Offensive of July–November 1916 was based on the RFC's air-shot photographs.

Artillery observation

One of the initial and most important uses of RFC aircraft was observing artillery fire behind the enemy front line at targets that could not be seen by ground observers. The fall of shot of artillery fire were easy enough for the pilot to see, providing he was looking in the right place at the right time; apart from this the problem was communicating corrections to the battery.

Development of procedures had been the responsibility of No 3 Squadron and the Royal Artillery in 1912–13. These methods usually depended on the pilot being tasked to observe the fire against a specific target and report the fall of shot relative to the target, the battery adjusted their aim, fired and the process was repeated until the target was effectively engaged. One early communication method was for the flier to write a note and drop it to the ground where it could be recovered but various visual signalling methods were also used. This meant the pilots had to observe the battery to see when it fired and see if it had laid out a visual signal using white marker panels on the ground.

The Royal Engineers' Air Battalion had pioneered experiments with wireless telegraphy in airships and aircraft before the RFC was created. Unfortunately the early transmitters weighed 75 pounds and filled a seat in the cockpit. This meant that the pilot had to fly the aircraft, navigate, observe the fall of the shells and transmit the results by morse code by himself. Also, the wireless in the aircraft could not receive. Originally only a special Wireless Flight attached to No. 4 Squadron RFC had the wireless equipment. Eventually this flight was expanded into No. 9 Squadron under Major Hugh Dowding. However, in early 1915 the Sterling lightweight wireless became available and was widely used. In 1915 each corps in the BEF was assigned a RFC squadron solely for artillery observation and reconnaissance duties. The transmitter filled the cockpit normally used by the observer and a trailing wire antenna was used which had to be reeled in prior to landing.

The RFC's wireless experiments under Major Herbert Musgrave, included research into how wireless telegraphy could be used by military aircraft. However, the most important officers in wireless development were Lieutenants Donald Lewis and Baron James in the RFC HQ wireless unit formed in France in September 1914. They developed both equipment and procedures in operational sorties.

An important development was the Zone Call procedure in 1915. By this time maps were 'squared' and a target location could be reported from the air using alphanumeric characters transmitted in Morse code. Batteries were allocated a Zone, typically a quarter of a mapsheet, and it was the duty of the RFC signallers on the ground beside the battery command post to pick out calls for fire in their battery's Zone. Once ranging started the airman reported the position of the ranging round using the clock code, the battery adjusted their firing data and fired again, and the process was repeated until the pilot observed an on-target or close round. The battery commander then decided how much to fire at the target.

The results were mixed. Observing artillery fire, even from above, requires training and skill. Within artillery units, ground observers received mentoring to develop their skill, which was not available to RFC aircrew. There were undoubtedly some very skilled artillery observers in the RFC, but there were many who were not and there was a tendency for 'optimism bias' – reported on-target rounds that weren't. The procedures were also time-consuming.

The ground stations were generally attached to heavy artillery units, such as Royal Garrison Artillery Siege Batteries, and were manned by RFC wireless operators, such as Henry Tabor.[16] These wireless operators had to fend for themselves as their squadrons were situated some distance away and they were not posted to the battery they were colocated with. This led to concerns as to who had responsibility for them and in November 1916 squadron commanders had to be reminded "that it is their duty to keep in close touch with the operators attached to their command, and to make all necessary arrangements for supplying them with blankets, clothing, pay, etc" (Letter from Headquarters, 2nd Brigade RFC dated 18 November 1916 – Public Records Office AIR/1/864)

The wireless operators' work was often carried out under heavy artillery fire in makeshift dug-outs. The artillery batteries were important targets and antennas were a lot less robust than the guns, hence prone to damage requiring immediate repair. As well as taking down and interpreting the numerous signals coming in from the aircraft, the operator had to communicate back to the aircraft by means of cloth strips laid out on the ground or a signalling lamp to give visual confirmation that the signals had been received. The wireless communication was one way as no receiver was mounted in the aircraft and the ground station could not transmit. Details from: "Henry Tabor's 1916 War Diary".

By May 1916, 306 aircraft and 542 ground stations were equipped with wireless.

Covert operations

An unusual mission for the RFC was the delivery of spies behind enemy lines. The first mission took place on the morning of 13 September 1915 and was not a success. The plane crashed, the pilot and spy were badly injured and they were both captured (two years later the pilot, Captain T.W. Mulcahy-Morgan escaped and returned to England). Later missions were more successful. In addition to delivering the spies the RFC was also responsible for keeping them supplied with the carrier pigeons that were used to send reports back to base. In 1916 a Special Duty Flight was formed as part of the Headquarters Wing to handle these and other unusual assignments.[citation needed]

Aerial bombardment

The obvious potential for aerial bombardment of the enemy was not lost on the RFC, and despite the poor payload of early war aircraft, bombing missions were undertaken. Front line squadrons (at the prompting of the more inventive pilots) devised several methods of carrying, aiming and dropping bombs. Lieutenant Conran of No 3 Squadron attacked an enemy troop column by dropping hand grenades over the side of his cockpit; the noise of the grenades caused the horses to stampede. At No 6 Squadron, Captain Louis Strange managed to destroy two canvas-covered trucks with home-made petrol bombs.

In March 1915 a bombing raid was flown, with Captain Strange flying a modified Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2c, to carry four 20 lb Cooper bombs on wing racks released by pulling a cable fitted in the cockpit. Attacking Courtrai railway station. Strange approached from low level and hit a troop train causing 75 casualties. The same day Captain Carmichael of No 5 Squadron dropped a 100 lb bomb from a Martinsyde S1 on the railway junction at Menin. Days later, Lieutenant William Barnard Rhodes-Moorhouse of No 2 Squadron was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross after bombing Courtrai station in a BE2c.

In October 1917 No 41 Wing was formed to attack strategic targets in Germany. Consisting of No 55 Squadron (Airco DH.4), No 100 (Royal Aircraft Factory F.E.2b) and No 16 (Naval) Squadron (Handley Page 0/100) the wing was based at Ochey commanded by Lt Colonel Cyril Newall. Its first attack was on Saarbrücken on 17 October with 11 DH-4s and a week later nine Handley Page O/100s carried out a night attack against factories in Saarbrücken, while 16 F.E.2bs bombed railways nearby. Four aircraft failed to return. The wing was expanded with the later addition of Nos 99 and 104 Squadrons, both flying the DH-4 into the Independent Air Force.

Ground attack – army support

Aircraft were increasingly engaged in ground attack operations as the war wore on, aimed at disrupting enemy forces at or near the front line and during offensives. While formal tactical bombing raids were planned and usually directed at specific targets, ground-attack was usually carried out by individual pilots or small flights against targets of opportunity. Although the fitted machine guns were the primary armament for ground attack, bomb racks holding 20 lb Cooper bombs were soon fitted to many single-seat aircraft. Ground attack sorties were carried out at very low altitude and were often highly effective, in spite of the primitive nature of the weaponry involved, compared with later conflicts. The moral effect on ground troops subjected to air attack could even be decisive. Such operations became increasingly hazardous for the attacking aircraft, as one hit from small arms fire could bring an aircraft down and troops learned deflection shooting to hit relatively slow moving enemy aeroplanes.

During the Battle of Messines in June 1917, Trenchard ordered the British crews to fly low over the lines and strafe all available targets. Techniques for Army and RFC co-operation quickly evolved and improved and during the Third Battle of Ypres over 300 aircraft from 14 RFC squadrons, including the Sopwith Camel, armed with four 9 kg (20 lb) bombs, constantly raided enemy trenches, troop concentrations, artillery positions and strongholds in co-operation with tanks and infantry.

The cost to the RFC was high, with a loss rate of ground attack aircraft approaching 30 per cent. The first British production armoured type, the Sopwith Salamander, did not see service during the First World War.

Home defence

In the UK the RFC Home Establishment was not only responsible for training air and ground crews and preparing squadrons to deploy to France, but providing squadrons for home defence, countering the German Zeppelin raids and later Gotha raids. The RFC (and the Royal Naval Air Service) initially had limited success against the German raids, largely through the problem of locating the attackers and having aircraft of sufficient performance to reach the operating altitude of the German raiders.

With the bulk of the operational squadrons engaged in France few could be spared for home defence in the UK. Therefore, training squadrons were called on to supply home defence aircraft and aircrews for the duration of the war. Night flying and defence missions were often flown by instructors in aircraft deemed worn-out and often obsolete for front-line service, although the pilots selected as instructors were often among the most experienced in the RFC.

The RFC officially took over the role of Home Defence in December 1915 and at that time had 10 permanent airfields. By December 1916 there were 11 RFC home defence squadrons:

| Squadron | Aircraft | Base |

|---|---|---|

| 33 (Home Defence) | FE2 | Gainsborough |

| 36 (Home Defence) | BE2, BE12, FE2 | Seaton Carew |

| 37 (Home Defence) | BE12, FE2 | Woodham Mortimer |

| 39 (Home Defence) | BE2 | Woodford Green |

| 43 (Home Defence) | 1½ Strutter | Northolt |

| 50 (Home Defence) | BE2, BE12 | Harrietsham |

| 51 (Home Defence) | BE2, BE12 | Hingham |

| 75 (Home Defence) | Avro 504NF | Goldington |

| 76 (Home Defence) | BE2, BE12 | Ripon |

| 77 (Home Defence) | BE2, BE12 | Turnhouse |

| 78 (Home Defence) | BE2, BE12 | Hove |

Saint-Omer

As the war moved into the period of the mobile warfare commonly called the Race to the Sea, the Corps moved forward again. On 8 October 1914 the RFC arrived in Saint-Omer and a headquarters was established at the aerodrome next to the local race course. Over the next few days the four squadrons arrived and for the next four years Saint-Omer was a focal point for all RFC operations in the field. Although most squadrons only used Saint-Omer as a transit camp before moving on to other locations, the base grew in importance as it increased its logistic support to the RFC.

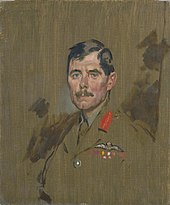

Trenchard in command in France

Hugh Trenchard was the commander of the Royal Flying Corps in France from August 1915 until January 1918. Trenchard's time in command was characterised by three priorities. First was his emphasis on support to and co-ordination with ground forces. This support started with reconnaissance and artillery co-ordination and later encompassed tactical low-level bombing of enemy ground forces. While Trenchard did not oppose the strategic bombing of Germany in principle, he opposed moves to divert his forces on to long-range bombing missions as he believed the strategic role to be less important and his resource to be too limited. Secondly, he stressed the importance of morale, not only of his own airmen, but more generally the detrimental effect that the presence of an aircraft had upon the morale of opposing ground troops. Finally, Trenchard had an unswerving belief in the importance of offensive action. Although this belief was widely held by senior British commanders, the RFC's offensive posture resulted in the loss of many men and machines and some doubted its effectiveness.[17]

1916–1917

Before the Battle of the Somme the RFC mustered 421 aircraft, with 4 kite-balloon squadrons and 14 balloons. These made up four brigades, which worked with the four British armies. By the end of the Somme offensive in November 1916, the RFC had lost 800 aircraft and 252 aircrew killed (all causes) since July 1916, with 292 tons of bombs dropped and 19,000 Recce photographs taken.

As 1917 dawned the Allied Air Forces felt the effect of the German Air Force's increasing superiority in both organisation and equipment (if not numbers). The recently formed Jastas, equipped with the Albatros fighter, inflicted very heavy losses on the RFC's obsolescent aircraft, culminating in Bloody April, the nadir of the RFC's fortunes in World War I.

To support the Battle of Arras beginning on 9 April 1917, the RFC deployed 25 squadrons, totalling 365 aircraft, a third of which were fighters (scouts). The British lost 245 aircraft with 211 aircrew killed or missing & 108 as prisoners of war. The German Air Services lost just 66 aircraft from all causes.

By the summer of 1917, the introduction of the next generation of technically advanced combat aircraft (such as the SE5, Sopwith Camel and Bristol Fighter) ensured losses fell and damage inflicted on the enemy increased.

Close support and battlefield co-operation tactics with the British Army were further developed by November 1917, when low-flying fighter aircraft co-operated highly effectively with advancing columns of tanks and infantry during the Battle of Cambrai.

1917 saw 2,094 RFC aircrew killed in action or missing.

Italy

The disastrous defeat of the Italian Army by Austro-Hungarian and German forces in the Battle of Caporetto led to the transfer of 3 RFC Sopwith Camel fighter squadrons (28, 45 and 66), two two-seater squadrons (34 and 42, with RE8s) and No. 4 Balloon Wing to the Italian Front in November 1917. No. 139 Squadron (Bristol Fighters) were added in July 1918.

Other theatres of operations

RFC Squadrons were also deployed to the Middle East and the Balkans. In July 1916 the Middle-East Brigade of the RFC was formed under the command of Brigadier General W G H Salmond, concentrating RFC units based in Macedonia, Mesopotamia, Palestine and East Africa under one unified command. In the Middle East units had to make do with older, often obsolete equipment before being given more modern aircraft. The Palestine Brigade of the RFC was formed in October 1917 to support General Allenby's ground offensive against the Ottomans in Palestine.

Despite their relatively small numbers the RFC gave valuable assistance to the Army in the eventual defeat of Ottoman forces in Palestine, Trans Jordan and Mesopotamia (Iraq).

1918

The German Offensive in March 1918 was an all-out effort to win the war before the German economy collapsed from the pressures exerted on it by the Royal Navy's blockade and the strains of war[18] In the weeks following the launch of the attack, RFC crews flew unceasingly, with all types of aircraft bombing and strafing ground forces, often from extremely low level, meantime also bringing back vital reports of the fluid ground fighting.

The RFC contributed significantly to slowing the German advance and ensuring the controlled retreat of the Allied Armies did not turn into a rout. The battle reached its peak on 12 April, when the newly formed RAF dropped more bombs, and flew more missions than any other day during the war. The cost of halting the German advance was high however, with over 400 aircrew killed and 1000 aircraft lost to enemy action.

Amalgamation with the RNAS

On 17 August 1917, General Jan Smuts presented a report to the War Council on the future of air power. Because of its potential for the 'devastation of enemy lands and the destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale', he recommended a new air service be formed that would be on a level with the Army and Royal Navy. Pilots were seconded to the RFC from other regiments and could return when they were no longer able to fly but in a separate service this would be impossible. The formation of the new service would make underused RNAS resources available for the Western Front, as well as ending the inter-service rivalry that at times had adversely affected aircraft procurement. On 1 April 1918, the RFC and the RNAS were amalgamated to form the Royal Air Force, under the control of a new Air Ministry. After starting in 1914 with some 2,073 personnel by the start of 1919 the RAF had 4,000 combat aircraft and 114,000 personnel.

Recruitment and training

Many pilots were initially seconded to the RFC from their original regiments by becoming an observer. Some RFC ground crew (often NCO's or below) also volunteered for these flying duties as they then received supplementary flying pay. There was no formal training for observers until 1917 and many were sent on their first sortie with only a brief introduction to the aircraft from the pilot. Once certified as fully qualified the observer was awarded the coveted half-wing brevet. Once awarded this could not be forfeited so it essentially amounted to a decoration. Originally in the RFC, as in most early air forces, the observer was nominally in command of the aircraft with the pilot having the role of a "chauffeur". In practice, this was reversed at an early stage in the RFC, so that the pilot normally commanded the aircraft. Most operational two seaters of the period did not have dual controls (an exception was the F.K. 8), so that the death or incapacity of the pilot normally meant an inevitable crash – but nonetheless many observers gained at least rudimentary piloting skills, and it was very common for experienced observers to be selected for pilot training.

Applicants for aircrew generally entered the RFC as a cadet via the depot pool for basic training. The cadet would then generally pass on to the School of Military Aeronautics at either Reading or Oxford. Following this period of theoretical learning the cadet was posted to a Training Squadron, either in the UK or overseas.

Colonel Robert Smith-Barry, a former CO of 60 Squadron, appalled at the poor standard of newly trained pilots and high fatality rate during training in 1915–16, formulated a comprehensive curriculum for pilot training, and with the agreement of Trenchard, returned to the UK to implement his training ethos at Gosport in 1917. The immediate effect was to halve fatalities in training. The curriculum was based on a combination of classroom theory and dual flight instruction. Students were not to be discouraged from potentially dangerous manoeuvres but were exposed to them in a controlled environment so that the student could learn to safely rectify errors of judgement.

Dual flying training usually weeded out those not suitable for flying training (approximately 45% of the initial class intake) before the remaining cadets were taught in the air by an instructor ( initially a 'tour-expired' pilot sent for a rest from an operational squadron in France, without any specific training on how to instruct). After flying 10 to 20 hours dual instruction, the pupil would be ready to 'go solo'.

In May 1916 pilots under instruction were further trained for fighting in the air. Schools of Special Flying were set up at Turnberry, Marske, Sedgeforth, Feiston, East Fortune and Ayr, where finished pilots could simulate combat flying under the supervision of veteran instructors.[19]

During 1917 experienced pilots were redeployed from the Sinai and Palestine campaign to set up a new flying school and train pilots in Egypt and staff another in Australia.[20] Seven Training Squadrons were eventually established in Egypt at five Training Depot Stations.

In 1917, the American, British, and Canadian Governments agreed to join forces for training. Between April 1917 and January 1919, Camp Borden in Ontario hosted instruction on flying, wireless, air gunnery and photography, training 1,812 RFC Canada pilots and 72 for the United States. Training also took place at several other Ontario locations.

During winter 1917–18, RFC instructors trained with the Aviation Section, US Signal Corps on three airfields in the United States accommodating about six thousand men, at Camp Taliaferro near Fort Worth, Texas. Training was hazardous; 39 RFC officers and cadets died in Texas. Eleven remain there, reinterred in 1924 at a Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery where a monument honours their sacrifice.

As the war drew on the RFC increasingly drew on men from across the British Empire including South Africa, Canada and Australia. As well as individual personnel, the separate Australian Flying Corps (AFC) deployed Nos 1, 2, 3 and 4 Squadrons AFC (which the RFC referred to as 67, 68, 69 and 71 Squadrons). Over 200 Americans joined the RFC before the United States became a combatant.[citation needed] Eventually Canadians made up nearly a third of RFC aircrew.[citation needed]

Although as the war progressed and training became far safer, by the end of the war, some 8,000 had been killed while training or in flying accidents.[19]

Parachutes

Parachuting from balloons and aircraft, with very few accidents, had been a popular "stunt" for several years before the war. In 1915 inventor Everard Calthrop offered the RFC his patented parachute. On 13 January 1917, Captain Clive Collett, a New Zealander, made the first British military parachute jump from a heavier-than-air craft. The jump, from 600 feet, was successful but although parachutes were issued to the crews of observation balloons, the higher authorities in the RFC and the Air Board were opposed to the issuing of parachutes to pilots of heavier-than-air craft. It was felt at the time that a parachute might tempt a pilot to abandon his aircraft in an emergency rather than continuing the fight. The parachutes of the time were also heavy and cumbersome, and the added weight was frowned upon by some experienced pilots as it adversely affected aircraft with already marginal performance. It was not until 16 September 1918 that an order was issued for all single-seater aircraft to be fitted with parachutes, and this did not eventuate until after the war.[2]

End of the war

At the end of the war there were 5,182 pilots in service (constituting 2% of total RAF personnel). In comparison, the casualties from the RFC/RNAS/RAF for 1914–18 totalled 9,378 killed or missing, with 7,245 wounded. Some 900,000 flying hours on operations were logged, and 6,942 tons of bombs dropped. The RFC claimed some 7,054 German aircraft and balloons either destroyed, sent 'down out of control' or 'driven down'.[21][22][page needed]

Eleven RFC members received the Victoria Cross during the First World War. Initially the RFC did not believe in publicising the victory totals and exploits of their aces. Eventually, however, public interest and the newspapers' demand for heroes led to this policy being abandoned, with the feats of aces such as Captain Albert Ball raising morale in the service as well as on the "home front". More than 1000 airmen are considered as "aces" (see List of World War I flying aces from the British Empire). However, the British criteria for confirming air victories were much lower compared to those from Germany or France and do not meet modern standards (see Aerial victory standards of World War I).

For a short time after the formation of the RAF, pre-RAF ranks such as Lieutenant, Captain and Major continued to exist, a practice which officially ended on 15 September 1919. For this reason some early RAF memorials and gravestones show ranks which no longer exist in the modern RAF. A typical example is James McCudden's grave, though there are many others.

Commanders and personnel

Commanders

The following had command of the RFC in the Field:

- Major General Sir David Henderson, 5 August 1914 – 22 November 1914

- Colonel F H Sykes, 22 November 1914 – 20 December 1914[23]

- Major General Sir David Henderson, 20 December 1914 – 19 August 1915

- Brigadier General, later Major General, H M Trenchard, 25 August 1915 – 3 January 1918

- Major General J M Salmond, 18 January 1918 – 4 January 1919 (General Officer Commanding the RAF in the Field from 1 April)

The following served as chief of staff for the RFC in the Field:

- Colonel Frederick Sykes 5 August 1914 – 22 November 1914

- Post vacant

- Colonel Frederick Sykes 20 December 1914 – 26 May 1915

- Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Brooke-Popham 26 May 1915 – 12 March 1916

- Brigadier General Philip Game 19 March 1916 – 14 October 1918 (RAF in the Field from 1 April)

Some members of the RFC

Militarily prominent

- Alfred Atkey – high scoring ace

- Albert Ball, VC – high scoring ace with 44 victories

- William George Barker – high scoring ace

- Billy Bishop, VC – first or second (see also Edward Mannock, below) highest scoring British Empire flying ace of World War I

- Donald Cunnell – high scoring ace

- Hugh Dowding – later commander of RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain

- Tryggve Gran – Norwegian ace 1916–21; had been member of Scott's 1910–13 Antarctic Expedition; first to fly across the North Sea, 1914

- Air Marshal Sir Arthur Harris ("Bomber" Harris) – later commander of RAF Bomber Command

- H. D. Harvey-Kelly, No. 2 Squadron – first RFC pilot to land in France at the outbreak of the First World War

- Lanoe Hawker VC, DSO – first British ace, killed in action by the "Red Baron" Manfred von Richthofen

- Jeejeebhoy Piroshaw Bomanjee Jeejeebhoy – first Indian pilot

- Air Marshal George Owen Johnson CB, MC RCAF

- Trafford Leigh-Mallory – later head of Fighter Command

- Donald MacLaren – high scoring ace

- James McCudden VC – high scoring ace with 57 victories

- George McElroy – high scoring ace

- Edward Mannock VC – although his score is disputed, often acknowledged as the first or second highest scoring British Empire ace

- John Moore-Brabazon, 1st Lord Brabazon of Tara – later Minister of Aircraft Production under Winston Churchill

- Eric Moxey – Captain in the RFC, later Squadron Leader in an RAF Special Duties squadron where he was killed at Biggin Hill and posthumously awarded the first George Cross of the Second World War

- Keith Park – commander of No. 11 Group, Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain

- Noel Stephen Paynter – later chief intelligence officer of RAF Bomber Command

- Sir Charles Portal – Chief of Air Staff throughout most of the Second World War

- Indra Lal Roy, DFC – first Indian ace, and the first Indian pilot to receive the DFC

- Arthur Tedder – Commander Allied Air Forces Mediterranean, Marshal of the Royal Air Force and Deputy Supreme Commander Allied Forces in the Second World War, Chief of the Air Staff 1946–1950

- Henry Tizard – scientist and inventor, chairman of the Aeronautical Research Committee 1933–44

- Hugh Trenchard – commander of RFC and later Chief of the Air Staff

Otherwise prominent

- Vernon Castle, ballroom dancer

- Sir Jack Cohen, founder of the Tesco supermarket chain

- O. G. S. Crawford, later Archaeology Officer of the Ordnance Survey

- Air Vice-Marshal Sir William Cushion, RAF and BOAC

- Charles Galton Darwin F.R.S., grandson of Charles Darwin

- Karl Brooks Heisey, mining engineer and executive

- Jack Hobbs, cricketer

- W. E. Johns, author of the Biggles books

- John Lennard-Jones, scientist

- Cecil Lewis, author of Sagittarius Rising

- Francis Peabody Magoun, Military cross winner 1918 and Harvard professor

- Oswald Mosley, founder of the British Union of Fascists

- Malcolm Nokes, Olympic medal winner, schoolmaster and scientist

- Mick O'Brien, footballer

- Cuthbert Orde, war artist noted for portraits of Battle of Britain pilots

- Phelps Phelps, 38th Governor of American Samoa and United States Ambassador to the Dominican Republic

- Sir Charles Kingsford Smith, Australian aviation pioneer, first to cross the Pacific Ocean in 1928 using Fokker trimotor monoplane Southern Cross. First to cross the Atlantic Ocean west to east. First to cross the Tasman Sea also using the Southern Cross. He also set many records for flying solo between England and Australia and vice versa.

- Robert Smith-Barry, systematised the training of pilots and set up a formal curriculum of flying training (the "Gosport System") that was subsequently taken up worldwide

- William Stephenson, head of British Security Coordination during the Second World War. Played key role in formation of the CIA. The first non-US citizen to receive the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

- George Morgan Trefgarne, 1st Baron Trefgarne

- Hubert Williams (1895–2002), last surviving Royal Flying Corps pilot. In 1995 on his 100th birthday he was allowed to take over the controls of a Concorde flying to New York.[24]

- William Young (1900–2007), last surviving veteran of the Royal Flying Corps

Fictional representations of the RFC

Novels and short stories

- Winged Victory (1934) by Victor M Yeates, a First World War pilot. Sought after by Battle of Britain pilots for its authentic descriptions of aerial warfare. Published by Jonathan Cape.

- The Biggles series (1932–1999): a series of youth-oriented novels and short story collections by W. E. Johns, an RFC veteran

- The Bandy Papers (1962–2005): a series of novels by Donald Jack chronicling the exploits of a fighter ace, Bartholomew Wolfe Bandy

- Goshawk Squadron (1971) and its prequels, by Derek Robinson

- The Bloody Red Baron (1995): the second novel of the alternate-history Anno Dracula series by Kim Newman, which primarily follows the exploits of a unit of the RFC and their enemy rivals

- Phoenix and Ashes (2004): a fantasy novel by Mercedes Lackey

- Across the Blood-Red Skies (2010), by Robert Radcliffe

Film and TV

- Hell's Angels (1930): a film directed by Howard Hughes, starring Jean Harlow

- The Dawn Patrol (1938): a film directed by Edmund Goulding, starring Errol Flynn, Basil Rathbone and David Niven (a remake of a 1930 original).

- "The Last Flight" (1960): an episode of The Twilight Zone TV series

- Aces High (1976): a film directed by Jack Gold, starring Malcolm McDowell, Christopher Plummer and Simon Ward

- Wings (1977–78): a BBC TV series

- "Private Plane" (1989): an episode of the Blackadder TV series

- "The Double Deuce" (2011) : an episode of the Archer TV series

Games

Songs

- The Hymn of Hate (1918)

RFC mess song recorded by Royal Flying Corps 2nd Lieut. Francis Stewart Briggs on 9 May 1918 at RFC "No. 1 School of Aerial Navigation and Bomb Dropping" Stonehenge, Wiltshire, UK.

See also

- Army Air Corps

- Canadian Aviation Corps

- Royal Canadian Naval Air Service

- Australian Flying Corps

- Union Defence Force

- South African Aviation Corps

- List of aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps

- List of Royal Air Force aircraft squadrons

- British unmanned aerial vehicles of World War I

Notes

- ^ Beckett, p. 254.

- ^ a b Lee (1968) pp. 219–225

- ^ "No. 28609". The London Gazette. 17 May 1912. p. 3583.

- ^ Full Text Archive. "A History of Aeronautics by E. Charles Vivian". Full Text Archive.

- ^ Air Ministry Weekly Order 109 (1921, reprint of 1923)

- ^ "British Military Aviation in 1917 – Part 2". Royal Air Force Museum. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012.

- ^ "CO 62 Sqn RFC/RAF". airwar1.org.uk.

- ^ "British Military Aviation in 1914 – Part 3". RAF Museum Web Site – Timeline of British Military Aviation History. RAF Museum. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- ^ "Wings 51 – 110_P". Archived from the original on 7 July 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ Boyle, Andrew (1962). "Chapter 6". Trenchard Man of Vision. St. James's Place London: Collins. p. 157.

- ^ "Saundby Aerodrome".

- ^ Raleigh 1922, p. 286.

- ^ "Casualty Details:Vincent Waterfall". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ Jackson 1990, p. 56.

- ^ The British Air Services Memorial at St Omer

- ^ "Henry Tabor's 1916 War Diary". Henry Tabor's 1916 War Diary. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ Jordan, David (2000). "The Battle for the Skies: Sir Hugh Trenchard as Commander of the Royal Flying Corps". In Matthew Hughes and Matthew Seligmann (ed.). Leadership in Conflict 1914–1918. Leo Cooper Ltd. pp. 74–80. ISBN 0-85052-751-1.

- ^ Ludendorff, Erich (1919). Meine Kriegserinnerungen, 1914–1918. Berlin: Nabu Press (5 November 2011).

- ^ a b 'First of the Few', Denis Winter, 1982

- ^ Cutlack 1941 pp. 69–70

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker (28 October 2014). World War I: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. ABC-CLIO. p. 696. ISBN 978-1-85109-965-8.

- ^ History of the RAF, Bowyer, 1977 (Hamlyn)

- ^ Ash, Eric (1998). Sir Frederick Sykes and the air revolution, 1912–1918. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 0-7146-4382-3.

- ^ "Hubert…last of the Flying Corps heroes; WW1 Ace Dies at 106". thefreelibrary.com.

References

- Barker, Ralph (2002). The Royal Flying Corps in World War I. Robinson. ISBN 1-84119-470-0.

- Drew, George A. (1930). Canada's Fighting Airmen. MacLean. OCLC 3234658.

- Lee, Arthur Gould (1968). No Parachute. Harrolds. Reprinted in 1971. ISBN 0671773461

- Jackson, A.J. (1990). Avro Aircraft since 1908 (Second ed.). London: Putnam. ISBN 0-85177-834-8.

- Raleigh, Walter (1922). The War in the Air: Being the Story of The part played in the Great War by The Royal Air Force: Vol I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 190162322X.

- Rimell, Ray (1985). The Royal Flying Corps in World War One. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 0853686939. OCLC 12807952.

External links

- Royal Engineers Museum Origins of the Royal Flying Corps/Royal Air Force

- Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and Aeronautics

- Army Air Corps

- RAF Museum

- The Museum of Army Flying

- https://web.archive.org/web/20050702075751/http://www.wwiaviation.com/toc.shtml

- http://www.spartacus-educational.com/FWWRFC.htm

- http://www.acepilots.com/wwi/br_mccudden.html

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070224071857/http://www.airforce.forces.ca/16wing/heritage/hist1_e.asp

- Bermudian Great War Aviators

- Silhouettes of Aeroplanes and Airships (RFC handbook, 1916)

- RFC Wireless Operator's diary from 1916 Battle of the Somme