Dunhuang

Dunhuang

敦煌市 Tunhwang | |

|---|---|

Dunhuang | |

Dunhuang City (red) in Jiuquan City (yellow) and Gansu | |

| Coordinates (Dunhuang municipal government): 40°08′28″N 94°39′50″E / 40.14111°N 94.66389°E | |

| Country | China |

| Province | Gansu |

| Prefecture-level city | Jiuquan |

| Municipal seat | Shazhou Town |

| Area | |

• Total | 31,200 km2 (12,000 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,142 m (3,747 ft) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

• Total | 185,231 |

| • Density | 5.9/km2 (15/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (CST) |

| Postal Code | 736200 |

| Website | www |

| Dunhuang | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Dunhuang" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 敦煌 | ||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Tunhwang | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Blazing Beacon"[citation needed] | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Dunhuang () is a county-level city in northwestern Gansu Province, Western China. According to the 2010 Chinese census, the city has a population of 186,027,[1] though 2019 estimates put the city's population at about 191,800.[3] Sachu (Dunhuang) was a major stop on the ancient Silk Road and is best known for the nearby Mogao Caves.

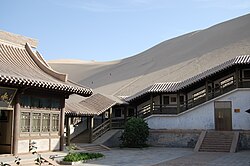

Dunhuang is situated in an oasis containing Crescent Lake and Mingsha Shan (鳴沙山, meaning "Singing-Sand Mountain"), named after the sound of the wind whipping off the dunes, the singing sand phenomenon. Dunhuang commands a strategic position at the crossroads of the ancient Southern Silk Route and the main road leading from India via Lhasa to Mongolia and southern Siberia,[4] and also controls the entrance to the narrow Hexi Corridor, which leads straight to the heart of the north Chinese plains and the ancient capitals of Chang'an (today known as Xi'an) and Luoyang.[5]

Administratively, the county-level city of Dunhuang is part of the prefecture-level city of Jiuquan.[6] Historically, the city and/or its surrounding region has also been known by the names Shazhou (prefecture of sand) or Guazhou (prefecture of melons).[4] In the modern era, the two alternative names have been assigned respectively to Shazhou zhen (Shazhou town) which serves as Dunhuang's seat of government, and to the neighboring Guazhou County.

Etymology

A number of derivations of the name Dunhuang have been suggested by scholars:

- Giles 1892: 墩煌 Dūnhuáng ‘artificial mound, tumulus, beacon mound, square block of stone or wood’ + ‘blazing, bright, luminous’.

- Mathews (1931) 1944: 敦煌 Tūnhuáng, now usually Dūnhuáng ‘regard as important, to esteem; honest, sincere, generous’ + ‘a great blaze; luminous, glittering’.

- McGraw-Hill 1963: 敦煌 Dūnhuáng (‘honest + shining’).

- Jáo and Demieville 1971 (French, Airs de Touen-houang): 燉煌 Dùn (tūn) huáng ‘noise of burning’ + ‘great blaze’ [per Mathews].

- Lín Yǚtáng 1972: 墩(煌) Dūn(huáng) ‘small mound (+ shining)’ or 燉(煌) Dùn(huáng) ‘to shimmer (+ shining)’.

- Kāngxī 1716: 燉煌 Tún huáng, also 敦煌 Tūn huáng [t=t’].

- Mair 1977, Ptolemy's c. 150 Geography refers to Dunhuang as Greek Θροανα (Throana), possibly from Iranian Druvana meaning something like "fortress for tax collecting."

History

Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties

There is evidence of habitation in the area as early as 2,000 BC, possibly by people recorded as the Qiang in Chinese history. According to Zuo Zhuan and Book of the Later Han, the Dunhuang region was a part of the ancient Guazhou, which was known for its production of delicious melons.[7] Its name was also mentioned in relation to the homeland of the Yuezhi in the Records of the Grand Historian. Some have argued that this may refer to the unrelated toponym Dunhong – the archaeologist Lin Meicun has also suggested that Dunhuan may be a Chinese name for the Tukhara, a people widely believed to be a Central Asian offshoot of the Yuezhi.[8]

During the Warring States period, the inhabitants of Dunhuang included the Dayuezhi people, Wusun people, and Saizhong people (Chinese name for Scythians). As Dayuezhi became stronger, it absorbed the Qiang tribes.

By the third century BC, the area became dominated by the Xiongnu, but came under Chinese rule during the Han dynasty after Emperor Wu defeated the Xiongnu in 121 BC.

Dunhuang was one of the four frontier garrison towns (along with Jiuquan, Zhangye and Wuwei) established by the Emperor Wu after the defeat of the Xiongnu, and the Chinese built fortifications at Dunhuang and sent settlers there. The name Dunhuang, meaning "Blazing Beacon", refers to the beacons lit to warn of attacks by marauding nomadic tribes. Dunhuang Commandery was probably established shortly after 104 BC.[9] Located in the western end of the Hexi Corridor near the historic junction of the Northern and Southern Silk Roads, Dunhuang was a town of military importance.[10]

"The Great Wall was extended to Dunhuang, and a line of fortified beacon towers stretched westwards into the desert. By the second century AD Dunhuang had a population of more than 76,000 and was a key supply base for caravans that passed through the city: those setting out for the arduous trek across the desert loaded up with water and food supplies, and others arriving from the west gratefully looked upon the mirage-like sight of Dunhuang's walls, which signified safety and comfort. Dunhuang prospered on the heavy flow of traffic. The first Buddhist caves in the Dunhuang area were hewn in 353."[11]

During the Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties, it was the main stop of communication between ancient China and the rest of the world and a major hub of commerce of the Silk Road. Dunhuang was the intersection city of all three main silk routes (north, central, south) during this time.

From the West also came early Buddhist monks, who had arrived in China by the first century AD, and a sizable Buddhist community eventually developed in Dunhuang. The caves carved out by the monks, originally used for meditation, developed into a place of worship and pilgrimage called the Mogao Caves or "Caves of a Thousand Buddhas."[12] A number of Christian, Jewish, and Manichaean artifacts have also been found in the caves (see for example Jingjiao Documents), testimony to the wide variety of people who made their way along the Silk Road.

During the time of the Sixteen Kingdoms, Li Gao established the Western Liang here in 400 AD. In 405 the capital of the Western Liang was moved from Dunhuang to Jiuquan. In 421 the Western Liang was conquered by the Northern Liang.

As a frontier town, Dunhuang was fought over and occupied at various times by non-Han people. After the fall of Han dynasty it came under the rule of various nomadic tribes, such as the Xiongnu during Northern Liang and the Turkic Tuoba during Northern Wei. The Tibetans occupied Dunhuang when the Tang Empire became weakened considerably after the An Lushan Rebellion; and even though it was later returned to Tang rule, it was under quasi-autonomous rule by the local general Zhang Yichao, who expelled the Tibetans in 848. After the fall of Tang, Zhang's family formed the Kingdom of Golden Mountain in 910,[13] but in 911 it came under the influence of the Uighurs. The Zhangs were succeeded by the Cao family, who formed alliances with the Uighurs and the Kingdom of Khotan.

During the Song dynasty, Dunhuang fell outside the Chinese borders. In 1036 the Tanguts who founded the Western Xia dynasty captured Dunhuang.[13] From the reconquest of 848 to about 1036 (i.e. era of the Guiyi Circuit), Dunhuang was a multicultural entrepot that contained one of the largest ethnic Sogdian communities in China following the An Lushan Rebellion. The Sogdians were Sinified to some extent and were bilingual in Chinese and Sogdian, and wrote their documents in Chinese characters, but horizontally from left to right instead of right to left in vertical lines, as Chinese was normally written at the time.[14]

Dunhuang was conquered in 1227 by the Mongols, and became part of the Mongol Empire in the wake of Kublai Khan's conquest of China under the Yuan dynasty.

During the Ming dynasty, China became a major sea power, conducting several voyages of exploration with sea routes for trade and cultural exchanges. Dunhuang went into a steep decline after the Chinese trade with the outside world became dominated by southern sea-routes, and the Silk Road was officially abandoned during the Ming dynasty. It was occupied again by the Tibetans c. 1516, and also came under the influence of the Chagatai Khanate in the early sixteenth century.[15]

Dunhuang was retaken by China two centuries later c. 1715 during the Qing dynasty, and the present-day city of Dunhuang was established east of the ruined old city in 1725.[16]

In 1988, Dunhuang was elevated from county to county-level city status.[1] On March 31, 1995, Turpan and Dunhuang became sister cities.[17]

Today, the site is an important tourist attraction and the subject of an ongoing archaeological project. A large number of manuscripts and artifacts retrieved at Dunhuang have been digitized and made publicly available via the International Dunhuang Project.[18] The spreading Kumtag Desert, the result of long-standing overgrazing of the surrounding land, has reached the edges of the city.[19]

In 2011 satellite images showing huge structures in the desert near Dunhuang surfaced online and caused a brief media stir.[20]

Culture

Buddhist caves

A number of Buddhist cave sites are located in the Dunhuang area, the most important of these is the Mogao Caves which is located 25 km (16 mi) southeast of Dunhuang. There are 735 caves in Mogao, and the caves in Mogao are particularly noted for their Buddhist art,[21] as well as the hoard of manuscripts, the Dunhuang manuscripts, found hidden in a sealed-up cave. Many of these caves were covered with murals and contain many Buddhist statues. Discoveries continue to be found in the caves, including excerpts from a Christian Bible dating to the Yuan dynasty.[22]

Numerous smaller Buddhist cave sites are located in the region, including the Western Thousand Buddha Caves, the Eastern Thousands Buddha Caves, and the Five Temple site. The Yulin Caves are located further east in Guazhou County.

Other historical sites

- Crescent Lake and Singing Sand Dunes

- The Yumen Pass, built in 111 BC, located 90 km (56 mi) northwest of Dunhuang in the Gobi desert.

- The Yang Pass

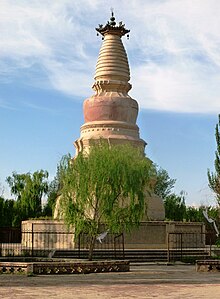

- White Horse Pagoda

- Dunhuang Limes

Museums

in Hecang Fortress (Chinese: 河仓城; pinyin: Hécāngchéng), located about 11 km (6.8 mi) northeast of the Western-Han-era Yumen Pass, were built during the Western Han (202 BC – 9 AD) and significantly rebuilt during the Western Jin (280–316 AD).[23]

Night market

Dunhuang Night Market is a night market held on the main thoroughfare, Dong Dajie, in the city centre of Dunhuang, popular with tourists during the summer months. Many souvenir items are sold, including such typical items as jade, jewelry, scrolls, hangings, small sculptures, leather shows puppets, coins, Tibetan horns and Buddha statues.[24] A sizable number of members of China's ethnic minorities engage in business at these markets. A Central Asian dessert or sweet is also sold, consisting of a large, sweet confection made with nuts and dried fruit, sliced into the portion desired by the customer.

Geography

Climate

Dunhuang has a cool arid climate (Köppen BWk), with an annual total precipitation of 67 mm (2.64 in), the majority of which occurs in summer; precipitation occurs only in trace amounts and quickly evaporates.[25] Winters are long and freezing, with a 24-hour average temperature of −8.3 °C (17.1 °F) in January, while summers are hot, with a July average of 24.6 °C (76.3 °F); the annual mean is 9.48 °C (49.1 °F). The diurnal temperature variation averages 16.1 °C (29.0 °F) annually. With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 69% in March to 82% in October, the city receives 3,258 hours of bright sunshine annually, making it one of the sunniest nationwide.

The Gansu Dunhuang Solar Park was built in the southwest suburbs of the city to harvest the abundant solar energy.

| Climate data for Dunhuang (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −0.8 (30.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

14.3 (57.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

27.7 (81.9) |

31.9 (89.4) |

33.5 (92.3) |

32.3 (90.1) |

27.3 (81.1) |

19.4 (66.9) |

9.3 (48.7) |

0.6 (33.1) |

18.7 (65.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −8.1 (17.4) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

5.9 (42.6) |

13.7 (56.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

25.8 (78.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

17.7 (63.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

1.2 (34.2) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −14.2 (6.4) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

15.9 (60.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−11.9 (10.6) |

2.9 (37.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1.2 (0.05) |

0.5 (0.02) |

2.1 (0.08) |

3.2 (0.13) |

5.7 (0.22) |

8.7 (0.34) |

11.2 (0.44) |

5.9 (0.23) |

2.7 (0.11) |

0.9 (0.04) |

1.1 (0.04) |

1.4 (0.06) |

44.6 (1.76) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 22 |

| Average snowy days | 3.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 11.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 54 | 39 | 33 | 28 | 30 | 37 | 42 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 49 | 56 | 42 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 221.9 | 220.9 | 265.1 | 288.1 | 328.3 | 321.6 | 317.9 | 315.0 | 294.9 | 283.8 | 231.7 | 209.9 | 3,299.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 73 | 72 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 72 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 84 | 79 | 73 | 75 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[26][27][28] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

As of 2020, Dunhuang administers nine towns and one other township-level division.[29] These township-level divisions then administer 56 village-level divisions.[6]

Towns

The city's nine towns are Qili (七里镇), Shazhou (沙州镇), Suzhou (肃州镇), Mogao (莫高镇), Zhuanqukou (转渠口镇), Yangguan (阳关镇), Yueyaquan (月牙泉镇), Guojiabu (郭家堡镇), and Huangqu (黄渠镇).[29]

Other township-level divisions

The city's sole other township-level division is Qinghai Petroleum Authority Life Base.[29]

Historical divisions

Prior to 2015, Guojiabu and Huangqu were administered as townships.[1] Prior to 2019, the city administered Guoying Dunhuang Farm as a township-level division.[30] In 2011, Yueyaquan was formed from Yangjiaqiao Township (Chinese: 杨家桥乡).[1]

Demographics

2019 city estimates put Dunhuang's population at about 191,800.[3] According to the 2010 Chinese census, Dunhuang has a population of 186,027, down slightly from the 187,578 recorded in the 2000 Chinese census.[1] In 1996, the city had an estimated population of 125,000 people.[1]

Dunhuang has an urbanization rate of 69.45% as of 2019.[3]

In 2019, the city had a birth rate of 9.87‰, and a death rate of 5.69‰, giving it a rate of natural increase of 3.15‰.[3]

97.8% of the city's population is ethnically Han Chinese, with the remaining 2.2% being 27 ethnic minorities, including ethnic Hui, Mongol, Tibetan, Uyghur, Miao, Manchu, Monguor, Kazakh, Dongxiang, and Yugur populations.[31]

As of 2019, the annual per capita disposable income of urban residents was ¥36,215, and the annual per capita disposable income of rural residents was ¥18,852.[3]

Economy

As of 2019, Dunhuang has a gross domestic product of ¥8.178 billion.[3] The value of the city's primary sector totaled ¥0.994 billion, its secondary sector totaled ¥1.872 billion, and its tertiary sector totaled ¥5.312 billion.[3]

As of 2020, Dunhuang has a gross domestic product of ¥7.778 billion. The value of the city's primary sector totaled ¥1.082 billion, its secondary sector totaled ¥1.752 billion, and its tertiary sector totaled ¥4.943 billion.[32]

Transportation

Dunhuang is served by China National Highway 215 and Dunhuang Mogao International Airport,

A railway branch known as the Dunhuang railway or the Liudun Railway (柳敦铁路), constructed in 2004–2006, connects Dunhuang with the Liugou Station on the Lanzhou-Xinjiang railway (in Guazhou County). There is regular passenger service on the line, with overnight trains from Dunhuang to Lanzhou and Xi'an.[33] Dunhuang Station is located northeast of town, near the airport.

The railway from Dunhuang was extended south into Qinghai, connecting Dunhuang to Subei, Mahai and Yinmaxia (near Golmud) on the Qingzang railway. The central section of this railway opened on 18 December 2019 completing the through route.[34]

See also

- Three hares (as a decorative motif)

- Major National Historical and Cultural Sites (Gansu)

- Bhadrakalpikasutra

- Dunhuang Star Chart

- Aurel Stein

- Mogao caves

- Paul Pelliot

- Yangguan

- Yueyaquan

Gallery

-

The Singing Sand Dunes on the eastern edge of the Kumtag Desert near Dunhuang.

-

Sculpture in Dunhuang, after a mural in Mogao Caves, depicting an Apsara playing the pipa behind her back (反弹琵琶伎乐天).

-

Mogao Caves, a.k.a. Dunhuang Grottoes.

-

Lonely monuments in the desert near Donghuan

-

Rammed earth ruins of a granary

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g 敦煌市历史沿革 [Dunhuang City Historical Development]. xzqh.org (in Chinese). 2016-06-27. Archived from the original on 2020-08-04. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- ^ "酒泉市第七次全国人口普查公报" (in Chinese). Government of Jiuquan. 2021-06-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g 敦煌市 2019 年国民经济和社会发展统计公报 [Dunhuang 2019 Economic and Social Development Statistical Report] (PDF) (in Chinese). Dunhuang People's Government. 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-02. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- ^ a b Cable and French (1943), p. 41.

- ^ Lovell (2006), pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b 行政区划 [Administrative Divisions] (in Chinese (China)). Dunhuang People's Government. Archived from the original on 2021-04-02. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- ^ "5". Book of the Later Han.

古瓜州,出美瓜。

- ^ Lin Meicun (1998 ), The Western Regions of the Han–Tang Dynasties and the Chinese Civilization [Chinese language only], Beijing, Wenwu Chubanshe, pp. 64–67.

- ^ Hulsewé, A. F. P. (1979). China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. Leiden, E. Brill, . pp.75–76 ISBN 90-04-05884-2

- ^ Hill (2015), Vol. I, pp. 137–140.

- ^ Bonavia (2004), p. 162.

- ^ The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia, by Frances Wood

- ^ a b "Dunhuang Studies – Chronology and History". Silkroad Foundation. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- ^ Galambos, Imre (2015), "She Association Circulars from Dunhuang", in Antje Richter, A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, Brill: Leiden, Boston, pp 853–77.

- ^ Tim Pepper (1996). Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (eds.). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. pp. 239–241. ISBN 978-1884964046.

- ^ Whitfield, Roderick; Susan Whitfield; Neville Agnew (2000). Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road. The British Library. ISBN 0-7123-4697-X.

- ^ 吐鲁番地区志. p. 64.

- ^ "The International Dunhuang Project". International Dunhuang Project. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Ancient Chinese town on front lines of desertification battle, AFP, Nov 20, 2007".

- ^ Wolchover, Natalie (16 November 2011). "Odd patterns in Chinese desert? Spy satellite targets.". NBC News.

- ^ Dunhuang Mogao caves art museum

- ^ "Syrian Language "Holy Bible" Discovered in Dunhuang Grottoes". en.people.cn.

- ^ Wang Xudang, Li Zuixiong, and Zhang Lu (2010). "Condition, Conservation, and Reinforcement of the Yumen Pass and Hecang Earthen Ruins Near Dunhuang", in Neville Agnew (ed), Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China, June 28 – July 3, 2004, 351–357. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, J. Paul Getty Trust. ISBN 978-1-60606-013-1, pp 351–352.

- ^ China. Eye Witness Travel Guides. p. 494.

- ^ "Dunhuang Climate − Best time to visit".

- ^ 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ^ "Experience Template" 中国气象数据网 (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ^ 中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年). China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ a b c 2020年统计用区划代码 [2020 Statistical Division Codes] (in Chinese). National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2020. Archived from the original on 2021-04-02. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- ^ 2018年统计用区划代码 [2018 Statistical Division Codes] (in Chinese). National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2018. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- ^ 人口民族 [Population and Ethnicity] (in Chinese). Dunhuang People's Government. Archived from the original on 2021-04-02. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- ^ http://www.dunhuang.gov.cn/userfiles/files/20210428/6375522292497513408525165.pdf Archived 2021-12-03 at the Wayback Machine[bare URL PDF]

- ^ "敦煌列车时刻表 敦煌火车时刻表 www.ip138.com". qq.ip138.com.

- ^ Briginshaw, David (18 December 2019). "Dunhuang railway in northwest China completed". International Railway Journal. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

References

- Baumer, Christoph. 2000. Southern Silk Road: In the Footsteps of Sir Aurel Stein and Sven Hedin. White Orchid Books. Bangkok.

- Beal, Samuel. 1884. Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, by Hiuen Tsiang. 2 vols. Trans. by Samuel Beal. London. Reprint: Delhi. Oriental Books Reprint Corporation. 1969.

- Beal, Samuel. 1911. The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang by the Shaman Hwui Li, with an Introduction containing an account of the Works of I-Tsing. Trans. by Samuel Beal. London. 1911. Reprint: Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi. 1973.

- Bonavia, Judy (2004): The Silk Road From Xi'an to Kashgar. Judy Bonavia – revised by Christoph Baumer. 2004. Odyssey Publications.

- Cable, Mildred and Francesca French (1943): The Gobi Desert. London. Landsborough Publications.

- Galambos, Imre (2015), "She Association Circulars from Dunhuang", in Antje Richter, A History of Chinese Letters and Epistolary Culture, Brill: Leiden, Boston, pp 853–77.

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation. Weilue: The Peoples of the West

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N. 1979. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. E. J. Brill, Leiden.

- Legge, James. Trans. and ed. 1886. A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: being an account by the Chinese monk Fâ-hsien of his travels in India and Ceylon (AD 399–414) in search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline. Reprint: Dover Publications, New York. 1965.

- Lok, Wai-ying. (2012). The significance of Dunhuang iconography from the perspective of Buddhist philosophy: a study mainly based on Cave 45 (PDF) (PhD Dissertation). The University of Hong Kong.

- Lovell, Julia (2006). The Great Wall : China against the World. 1000 BC — AD 2000. Atlantic Books, London. ISBN 978-1-84354-215-5.

- Mair, Victor. 2019. Greeks in ancient Central Asia: the Ionians. Language Log, 20 October 2019.

- Skrine, C. P. (1926). Chinese Central Asia. Methuen, London. Reprint: Barnes & Noble, New York. 1971. ISBN 0-416-60750-0.

- Stein, Aurel M. 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols. Clarendon Press. Oxford. National Institute of Informatics / Digital Archive of Toyo Bunko Rare Books – Digital Silk Road Project

- Stein, Aurel M. 1921. Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, 5 vols. London & Oxford. Clarendon Press. Reprint: Delhi. Motilal Banarsidass. 1980. National Institute of Informatics / Digital Archive of Toyo Bunko Rare Books – Digital Silk Road Project

- Watson, Burton (1993). Records of the Grand Historian of China. Han Dynasty II. (Revised Edition). New York, Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08167-7

- Watters, Thomas (1904–1905). On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India. London. Royal Asiatic Society. Reprint: 1973.

External links

- The International Dunhuang Project – includes tens of thousands of digitised manuscripts and paintings from Dunhuang, along with historical photographs and archival material

- Dunhuang at the British Museum (accessed 30 Jan 2018)

- Qianfodong at the British Museum (accessed 30 Jan 2018)

- Dunhuang Collection at the National Museum of India

- "Dunhuang". Silk Road Seattle. USA: Walter Chapin Simpson Center for the Humanities, University of Washington.