Lovejoy Columns

| Lovejoy Columns | |

|---|---|

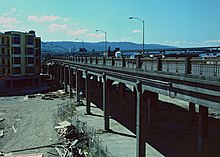

The columns in April 2013 | |

| |

| Artist | Athanasios Efthimiou "Tom" Stefopoulos |

| Year |

|

| Location | Portland, Oregon, United States |

| 45°31′32″N 122°40′52″W / 45.52557°N 122.68102°W | |

The Lovejoy Columns, located in Portland, Oregon, United States, supported the Lovejoy Ramp, a viaduct that from 1927 to 1999 carried the western approach to the Broadway Bridge over the freight tracks in what is now the Pearl District. The columns were painted by Greek immigrant Tom Stefopoulos between 1948 and 1952. In 1999, the viaduct was demolished but the columns were spared due to the efforts of the architectural group Rigga. For the next five years, attempts to restore the columns were unsuccessful and they remained in storage beneath the Fremont Bridge.

In 2005, two of the original columns were resited at Northwest 10th Avenue between Everett and Flanders Streets. The Regional Arts & Culture Council was searching for photographs showing the murals in their original location for an ongoing restoration project. In 2006, Randy Shelton reconstructed the artworks on the columns using the photographs for reference.

Description and history

The Lovejoy Columns supported the Lovejoy Ramp, a 2,000-foot (610 m)[1] viaduct that stretched from Northwest 14th Avenue and Lovejoy Street to the Broadway Bridge. It was constructed in 1927–1928.[2][3][4] Between 1948 and 1952, Athanasios Efthimiou "Tom" Stefopoulos (died 1971), a Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway night watchman, artist and master calligrapher in the copperplate style, drew upon the columns in chalk and later painted them.[5][6][7][8] His work was spontaneous and not commissioned.[9] Stefopoulos painted Greek mythology and Americana imagery in a calligraphic style; the designs depicted "fanciful" owls, landscapes "bedecked with homespun aphorisms", and ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes of Sinope navigating the streets of Athens with a lantern.[5][7] He painted around a dozen murals, though photographic evidence does not exist for each of them.[7] The paintings became a local landmark and quickly gained Stefopoulos notoriety and media coverage.[2][7]

In the late 1990s, developer Homer Williams persuaded the city to demolish the viaduct to open up dozens of blocks in the redeveloping Pearl District.[5] Preservation efforts began immediately. In 1998, Georgiana Nehl completed a painting of the columns called Guardians: Under the Lovejoy Ramp to "catch a small flavor of these 'guardians,' while they were still in place in their surprising location—before they were lost in the name of progress".[10] In 1999, James Henderson took a series of photographs of the remaining pigments of the original paintings; he recorded the murals using cross-polarized lighting and used digital enhancement to restore the colors.[11] The Regional Arts & Culture Council administers at least six of Henderson's photographs, which were printed in 2002 and each called Lovejoy Column.[11][12]

Demolition

The viaduct was removed in 1999,[4][13] but the architectural group Rigga persuaded the city to preserve the paintings and the columns. Rigga said that if the murals had been removed from the columns, "much of their magic would be lost".[7] The City of Portland's Office of Transportation earmarked funds to remove ten columns; an ad hoc committee called Friends of the Columns was formed to raise money for their storage, restoration and public display, which was estimated to cost $460,000.[14] City Commissioner Charlie Hales said, "Saving the Lovejoy columns and the artwork provides a real bridge between the rich history of this industrial area and its future as a residential neighborhood. I am pleased that we are able to save these columns and look forward to them being placed on some of the park spaces in the River District."[14] According to the James M. Harrison Art and Design Studio, "Extracting the columns both captured the space created by Tom and preserved a ruin that would continue to tell a story. The fragile paintings preserved the mighty concrete."[7] During the next five years, attempts by the city, and non-profit and entrepreneurial groups to restore the columns were unsuccessful.[5] Boora Architects' Northwest Marshall Street Pedestrian Bridge Feasibility Study (2001), funded by the Portland Development Commission, proposed installing the columns at the intersection of Northwest 9th Avenue and Naito Parkway.[15]

The columns were featured in a 2003 article by the Getty Conservation Institute called "The Conservation of Outdoor Contemporary Murals", which described best practices for preserving murals and included photographs of the columns during the demolition phase, with conservator J. Claire Dean assessing one of them.[16] From August 10 to September 4, 2004, Portland-based artist and filmmaker Vanessa Renwick exhibited a paper and video installation called Lovejoy Lost, featuring camera work by her and Gus Van Sant, for the PDX Window Project.[17][18]

In November 2004, Willamette Week reported that the columns were being held at a storage yard at Northwest 14th Avenue and Savier Street, beneath the Fremont Bridge. The paper said, "[h]alf-covered in blue tarps, their rusted steel girders sticking out of concrete like veins from a freshly amputated arm, they await the political momentum to rescue them from rot".[5] Real estate developer John Carroll hoped to site the columns at the Elizabeth Lofts, but former Rigga member James Harrison said he was reluctant to believe it would happen, given their history. Harrison told Willamette Week, "[t]hese things can turn on a dime".[5]

Resiting

Carroll's and Harrison's efforts were realized in 2005 when two of the ten original columns were resited at Northwest 10th Avenue between Everett and Flanders streets. The 29,000 lb (13,000 kg) columns featured a majority of Stefopoulos' paintings.[6][7] Harrison reportedly watched with "something like fatherly joy" during the installation and said, "[w]e're installing a ruin".[19] Carroll said displaying the columns as public art "will preserve an element of the city’s past for current and future generations" and acknowledged support from the neighborhood, Friends of the Columns and the Portland Development Commission.[20] The Regional Arts & Culture Council was searching for photographs showing the murals in their original location for a restoration project, which would be completed the following summer.[19] In 2006, the columns were reconstructed from the photographs by Randy Shelton.[6][7] The City of Portland's Bureau of Planning said the resited columns "[celebrate] a period in the district’s history, showcasing the art for a broader audience".[21]

An event called "Public Space Invasion" was held in the plaza containing the columns in 2011, inviting guests to "explore the legal limits of Portland's more peculiar public spaces". It advertised "crafts among the condos" and the opportunity to "picnic beside a freeway".[22][23] In 2013, a bicycle tour called "Lovejoy Columns and Tom" focused on the conservation of the columns, the "almost forgotten history" of Stefopoulos and the rise of the Pearl District. The tour was narrated by Harrison on behalf of Friends of the Columns and guided by "Portland's Museum Lady" Carye Bye; it raised money for a gravestone for Stefopoulos' unmarked grave at Rose City Cemetery. It included a guided tour at the Hellenic-American Cultural Center and Museum, which was exhibiting Master Penworks of Tom Stefopoulos to view pen-and-ink art by Stefopoulos. It also included a viewing of Renwick's unfinished film Lovejoy and an optional visit to Stefopoulos' grave.[8][24] In her documentary, Renwick chronicled the effort to save the columns and restore the paintings.[7]

Depictions and reception

The Daily Journal of Commerce called the columns a Portland "urban legend".[14] According to Richard Speer of Willamette Week, "generations of Portlanders grew up counting the Lovejoy columns as one of the city's most unique attractions". Speer also said the columns were once "postcard favorites and seemed as much a part of the city's landscape as the Hawthorne Bridge" and have an "endearing, perspectiveless style".[5] The murals appeared in Van Sant's film Drugstore Cowboy (1989), Foxfire (1996) and a music video featuring Elliott Smith.[18]

The resited columns have been included in published walking tours of Portland.[2][3][25] In her 2006 book Walking Portland: 30 Tours of Stumptown's Funky Neighborhoods, Historic Landmarks, Park Trails, Farmers Markets, and Brewpubs, Becky Ohlsen said, "Whatever you make of the artwork, the inspired effort that went into preserving it—not to mention the awesome spectacle of those massive columns ripped free, their rebar guts exposed to the air—is damned impressive".[2]

See also

References

- ^ Stewart, Bill (June 10, 1999). "Lovejoy Ramp will soon be a memory". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. p. C2.

- ^ a b c d Ohlsen, Becky (April 9, 2013). Walking Portland: 30 Tours of Stumptown's Funky Neighborhoods, Historic Landmarks, Park Trails, Farmers Markets, and Brewpubs. Wilderness Press. p. 16. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ a b Foster, Laura O. (2008). Portland City Walks: Twenty Explorations in and Around Town. Timber Press. p. 207. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ a b Gragg, Randy (August 1, 1999). "Romantic's eulogy for Lovejoy Ramp: The old viaduct must move aside for progress, but some of us will lament the loss". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. p. F10.

- ^ a b c d e f g Speer, Richard (November 10, 2004). "Pillars of the Community: The Lovejoy Columns, urban landmark". Willamette Week. Portland, Oregon: City of Roses Newspapers. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c "A Guide to Portland Public Art" (PDF). Regional Arts & Culture Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 29, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "The Lovejoy Columns Project". James M. Harrison Art and Design Studio. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "Master Penworks of Tom Stefopoulos Exhibit". Hellenic-American Cultural Center & Museum of Oregon and SW Washington. July 21, 2013. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ "Developing Public Art in Oregon's Rural Communities" (PDF). Arts Build Communities Technical Assistance Program (Oregon Arts Commission). October 2000. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ^ "Public Art Search: Guardians: Under the Lovejoy Ramp". Regional Arts & Culture Council. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ a b Regional Arts & Culture Council:

- "Public Art Search: Lovejoy Column (recid=1980.178)". Regional Arts & Culture Council. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- "Public Art Search: Lovejoy Column (recid=1997.173)". Regional Arts & Culture Council. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- "Public Art Search: Lovejoy Column (recid=1998.191)". Regional Arts & Culture Council. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ Regional Arts & Culture Council:

- "Public Art Search: Lovejoy Column (recid=2004.155)". Regional Arts & Culture Council. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- "Public Art Search: Lovejoy Column (recid=2005.152)". Regional Arts & Culture Council. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- "Public Art Search: Lovejoy Column (recid=2006.156)". Regional Arts & Culture Council. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ "Ramping down [photograph and caption only]". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. November 2, 1999.

The last pieces of the 73-year-old Northwest Lovejoy Street viaduct and the 10th Avenue ramp to the Broadway Bridge are being removed this week.

- ^ a b c "Tumblin' down: Lovejoy Viaduct a casualty of progress". Daily Journal of Commerce. August 19, 1999. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "NW Marshall Street Pedestrian Bridge Feasibility Study". Boora Architects, Inc. October 31, 2001. pp. 10, 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 24, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ Rainer, Lesie (Summer 2003). "The Conservation of Outdoor Contemporary Murals". Getty Conservation Institute. Archived from the original on January 24, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Lovejoy Lost: August 10, 2004 to September 4, 2004". PDX Contemporary Art. Archived from the original on December 25, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "Lovejoy Lost". Oregon Department of Kick Ass: The Work of Vanessa Renwick. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "Who's coming to town and who's leaving". Willamette Week. Portland, Oregon: City of Roses Newspapers. October 12, 2005. Archived from the original on September 28, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ Smith, Kennedy (October 6, 2005). "Columns adorned with Greek art relocate to Elizabeth Lofts". Daily Journal of Commerce. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ "River District Design Guidelines". City of Portland Bureau of Planning. 2008. p. 33. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|4=(help) Note: Adopted by the Portland City Council 1996. Amended November 1998, November 2008. Ordinance 182319. - ^ "Lovejoy Columns". The Portland Mercury. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ "Public Space Invasion". The Portland Mercury. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ "Lovejoy Columns and Tom Bike Ride":

- "Lovejoy Columns and Tom – Bike Ride Tour". Hellenic-American Cultural Center and Museum. October 1, 2013. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- Maus, Jonathan (October 10, 2013). "Weekend Event Guide: October 12–13". BikePortland.org. PedalTown Media Inc. Archived from the original on September 15, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- Moscato, Marc (October 13, 2013). "Lovejoy Columns and Tom Bike Ride". Archived from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- "Lovejoy Columns & Tom Bike Tour". The Portland Mercury. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Cook, Sybilla Avery (April 2, 2013). Walking Portland, Oregon. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 60–61. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

External links

- Lovejoy Columns, 1927 at cultureNOW

- Portland Then/Now: Northwest 12th Avenue and Lovejoy Street by Byron Beck (October 2, 2014), GoLocalPDX

- Historic Bicycle Tour of Northwest Portland, page 13 (PDF), Northwest District Association

- 1928 establishments in Oregon

- 1940s murals

- 1950s murals

- 1952 establishments in Oregon

- 2006 establishments in Oregon

- Birds in art

- Columns and entablature

- Demolished buildings and structures in Portland, Oregon

- Greek Antiquity in art and culture

- Murals in Oregon

- Outsider art

- Pearl District, Portland, Oregon

- Public art in the United States

- Works by American people

- Works by Greek people