Capital punishment in Russia

Currently, capital punishment in Russia[1] is not enforced. Russia has both an implicit moratorium established by President Boris Yeltsin in 1996, and an explicit one, established by the Constitutional Court of Russia in 1999 and most recently reaffirmed in 2009. Russia has not executed anyone since 1996.

History

The Russian death penalty

In pre-Tsarist medieval Russia capital punishment was relatively rare, and was even banned in many, if not most, principalities. The Law of Yaroslavl (c. 1017) put restrictions on what crimes warranted execution. Later, the law was amended in much of the country to completely ban capital punishment.[citation needed]

The Russian Empire practiced the death penalty extensively, as did almost all modern states before the 20th century. One of the first legal documents resembling a modern penal code was enacted in 1398, which mentioned a single capital crime: a theft performed after two prior convictions (an early precursor to the current Three-strikes laws existing in several U.S. states). The Pskov Code of 1497 extends this list significantly, mentioning three specialized theft instances (those committed in a church, stealing a horse, or, as before, with two prior "strikes"), as well as arson and treason. The trend to increase the number of capital crimes continued: in 1649, this list included 63 crimes, a figure that nearly doubled during the reign of Tsar Peter I (Peter the Great). The methods of execution were extremely cruel by modern standards (but fully consistent with the standards of the time), and included drowning, burying alive, and forcing liquid metal into the throat.[2]

Elizabeth (reigned 1741–1762) did not share her father Peter's views on the death penalty, and officially suspended it in 1745, effectively enacting a moratorium. This lasted for 11 years, at which point the death penalty was permitted again, after considerable opposition to the moratorium from both the nobility and, in part, from the Empress herself.[2]

Perhaps the first public statement on the matter to be both serious and strong came from Catherine II (Catherine the Great), whose liberal views were consistent with her acceptance of the Enlightenment. In her Nakaz of 1767, the empress expressed a disdain for the death penalty, considering it to be improper, adding: "In the usual state of the society, death penalty is neither useful nor needed." However, an explicit exception was still allowed for the case of someone who, even while convicted and incarcerated, "still has the means and the might to ignite public unrest".[3] This specific exception applied to mutineers of Pugachev's Rebellion in 1775. Consistent with Catherine's stance, the next several decades marked a shift of public perception against the death penalty. In 1824, the very existence of such a punishment was among the reasons for the legislature's refusal to approve a new version of the Penal Code. Just one year later, the Decembrist revolt failed, and a court sentenced 36 of the rebels to death.[2] Nicholas I's decision to commute all but five of the sentences was highly unusual for the time, especially taking into account that revolts against the monarchy had almost universally resulted in an automatic death sentence, and was perhaps[original research?] due to society's changing views of the death penalty.[citation needed] By the late 1890s, capital punishment for murder was virtually never carried out, but substituted with 10 to 15 years imprisonment with hard labor, although it still was carried out for treason (for example, Alexander Ulyanov was hanged in 1887). However, in 1910, capital punishment was reintroduced and expanded, although still very seldom used.[citation needed]

Russian Republic

The death penalty was officially outlawed on March 12, 1917 following the February Revolution and the establishment of the Russian Republic. On May 12, 1917, the death penalty became allowed for soldiers on the front.[4]

RSFSR and the Soviet Union

The Soviet government confirmed the abolition almost immediately after assuming power, but restored it for some crimes very soon. Most notably, Fanny Kaplan was executed on 4 September 1918 for her attempt to assassinate Lenin six days earlier. Over the next several decades, the death penalty was alternately permitted and prohibited, sometimes in very quick succession. The list of capital crimes likewise underwent several changes.

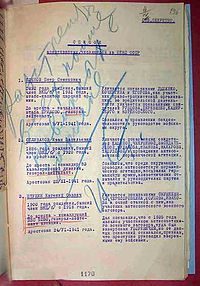

Under the rule of Joseph Stalin, many were executed during the Great Purge in the 1930s. Many of the death sentences were pronounced by a specially appointed three-person commission of officials, the NKVD troika.[5] The exact number of executions is debated, with archival research suggesting it to be between 700,000 and 800,000, whereas an official report to Nikita Khrushchev from 1954 cites 642,980 death penalties.[6] (see also Joseph Stalin § Death toll and allegations of genocide). The verdict of capital punishment in the Soviet Union was called the "Supreme Degree of Punishment" (Vysshaya Mera Nakazaniya, VMN). Verdicts under Article 58 (counter-revolutionary activity) often ended with a sentence that was abbreviated as VMN, and usually followed by executions through shooting, though other frequent verdicts were 10 years and 25 years (dubbed "Сталинский четвертак" Stalinskiy chetvertak, "Stalin's Quarter") sentences.

The death penalty was again abolished on 26 May 1947, the strictest sentence becoming 25 years' imprisonment, before it was restored on 12 May 1950:[7][8] first for treason and espionage, and then for aggravated murder.[2][4] The Penal Code of 1960 significantly extended the list of capital crimes. According to 1985–1989 statistics, the death penalty accounted for less than 1 in 2000 sentences.[citation needed] According to the GARF archives database, between 1978 and 1985 there were 3,058 sentences to death that had been appealed to the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR.[9] At least one woman was executed during this time, Antonina Makarova, on 11 August 1978.[10] After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation carried out the death penalty intermittently, with up to 10 or so officially a year. In 1996, pending Russia's entry into the Council of Europe, a moratorium was placed on the death penalty, which is still in place as of 2020.

Current status

Statute limitations

Article 20 of the Russian Constitution states that everyone has the right to life, and that "until its abolition, death penalty may only be passed for the most serious crimes against human life." Additionally, all such sentences require jury trial.[11] The inclusion of the abolition wording has been interpreted by some[4] as a requirement that the death penalty be abolished at some point in the future.

The current Penal Code[12] permits the death penalty for five crimes:

- murder, with certain aggravating circumstances (article 105.2)

- encroachment on the Life of a Person Administering Justice or Engaged in a Preliminary Investigation (article 295)

- encroachment on the Life of an Officer of a Law-enforcement Agency (article 317)

- encroachment on the Life of a Statesman or a Public Figure (article 277)

- genocide (section 357)

No crime has a mandatory death sentence; each of the five sections mentioned above also permit a sentence of life imprisonment as well as a prison term of not less than eight or twelve (depending on the crime) nor more than thirty, years. Moreover, men under the age of 18 or above the age of 60 as of the time the crime was committed, and all women, are not eligible for a death sentence.[2]

The Penal Execution Code specifies that the execution is to be carried out "non-publicly by means of shooting".[13]

Moratorium

One of the absolute requirements of the Council of Europe for all members is that the death penalty cannot be carried out for any crime. While the preferred method is abolition, the Council has demonstrated that it would accept a moratorium, at least temporarily. Consistent with this rule, on 25 January 1996, the Council required Russia to implement a moratorium immediately and fully abolish death penalty within three years, in order for its bid for inclusion in the organization be to be approved. In a little over a month, Russia agreed and became a member of the Council.[14] Whether the moratorium has actually happened as a matter of legal right is the subject of some controversy.[15]

On 16 May 1996, then-President Boris Yeltsin issued a decree "for the stepwise reduction in application of the death penalty in conjunction with Russia's entry into the Council of Europe", which is widely cited as de facto establishing such a moratorium. The decree called on the legislature to prepare a law which would abolish the death penalty, as well as a recommendation to decrease the number of capital crimes and require the authorities to treat those on the death row in a humane manner.[15] Although the order may be read as not specifically outlawing the death penalty, this was eventually the practical effect, and it was accepted as such by the Council of Europe as Russia was granted membership in the organization. However, since the executions continued in the first half of 1996 - that is, after Russia signed the agreement - the Council was not satisfied and presented Russia with several ultimatums, threatening to expel the country if the death penalty continues to be carried out. In response, several more laws and orders have been enacted, and Russia has not executed anyone since August 1996.[14] The last person to be executed in Russia was a serial killer named Sergey Golovkin, who was convicted in 1994 and shot on 2 August 1996.

On 2 February 1999, the Constitutional Court of Russia issued a temporary stay on any executions for a rather technical reason, but nevertheless granting the moratorium an unquestionable legal status for the first time. According to the Constitution as quoted above, a death sentence may be pronounced only by a jury trial, which were not yet implemented in some regions of the country. The court found that such disparity makes death sentences illegal in any part of the country, even those that do have the process of trial by jury implemented. According to the ruling, no death sentence may be passed until all regions of country have jury trials.[15]

On 15 November 2006, the Duma extended both the implementation of jury trials in the sole remaining region (Chechnya) and the moratorium on the death penalty by three years, until early 2010.[16]

Shortly before the end of this moratorium, on 19 November 2009, the Constitutional Court of Russia extended the national moratorium "until the ratification of 6th Protocol to the European Convention of Human Rights".[1] The court also ruled that the introduction of jury trials in Chechnya is not a valid precept for lifting the moratorium.

In April 2013, President Vladimir Putin said that lifting the moratorium was inadvisable.[17]

Public opinion

According to a 2006 survey by Fond Obschestvennoe Mneniye (Public Opinion Foundation), which was conducted on the 10th anniversary of the moratorium, the death penalty was supported by three quarters of the respondents, and only four percent of them favored the abolition of the death penalty. The moratorium itself was opposed by 55 percent of the respondents and supported by 28 percent of the respondents. Those supporting the moratorium had, on average, a higher level of education, lived in large cities and were younger.[18]

A survey conducted by the same company in 2012 (on a sample of 3,000) found that 62 percent of the respondents favored a return to the use of the death penalty, and 21 percent still supported the moratorium. In this survey, five percent of the respondents supported the abolition of the death penalty, and 66 percent supported the death penalty as a valid punishment.[19]

According to a 2013 survey by the Levada Center, 54 percent of the respondents favored an equal (38 percent) or greater (16 percent) use of the death penalty as before the 1996 moratorium, a decline from 68 percent in 2002 and from 61 percent in 2012. This survey found that the death penalty now has a higher approval rating in urban areas (77 percent in Moscow for example), with men and among the elderly.[17][20] According to the Levada Center figures, the proportion of Russians seeking abolition of the death penalty was 12 percent in 2002, 10 percent in 2012 and 11 percent in 2013. According to the same source, the proportion of Russians approving of the moratorium increased from 12 percent in 2002 to 23 percent in 2013.[17]

In 2015, the share of those who supported the death penalty had decreased to 41 percent, with 44 percent opposed. A February 2017 survey showed a small increase of support, with 44 percent of Russians wanting the death penalty returned and 41 percent saying they opposed such a measure. 15 percent of respondents said they did not have any opinion on the issue.[21]

Russian opinion on the practice in Europe

After two terrorists were executed in Belarus in 2012 for their role in the 2011 Minsk Metro bombing, the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that he urged all European countries to join the moratorium, including Belarus. However, he said that it is an internal affair of each state, and that despite condemning the execution that Russia still was a major supporter of the war on terror.[22]

Procedure

Historically, various types of capital punishment were used in Russia, such as hanging, breaking wheel, burning, beheading, flagellation by knout until death etc. During the times of Ivan the Terrible, capital punishment often took exotic and torturous forms, impalement being one of its most common types.[23] Certain crimes incurred specific forms of capital punishment, e.g. coin counterfeiters were executed by pouring molten lead into their throats, while certain religious crimes were punishable by burning alive.[24]

In the times after Peter the Great, hanging for military men and shooting for civilians became the default means of execution,[25] though certain types of non-lethal corporal punishment, such as lashing or caning, could result in the convict's death.[26]

In the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia, convicts awaited execution for a period around 9–18 months since the first sentence. That was the time typically needed for 2-3 appeals to be processed through the Soviet juridical system, depending on the level of the court that first sentenced the convict to death. Shooting was the only legal means of execution, though the exact procedure has never been codified. Unlike most other countries, execution did not involve any official ceremony: the convict was often given no warning and taken by surprise in order to eliminate fear, suffering and resistance.[citation needed] Where warning was given, it was usually just a few minutes.[citation needed]

The process was usually carried out by single executioner, usage of firing squads being limited to wartime executions. The most common method was to make the convict walk into a dead-end room, and shoot him from behind in the back of the head with a handgun.[27][28][29] In some cases, the convict could be forced down on his knees.[30] Some prisons were rumored to have specially designed rooms with fire slits,[27] while in others the convict was tied to the floor, his head against a blood draining hole.[30] Another method was to make the convict walk out of the prison building, where he was awaited by the executioner and a truck with the engine and headlamps turned on. The lights blinded and disoriented the convict, while the noise of the engine muffled the shot.[31] Sometimes the execution was carried out outdoors in front of the grave in which the convict was to be buried.[32]

The bodies of the executed criminals and political dissidents were not given to the relatives, but rather buried in anonymous graves in undisclosed locations.[33]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Конституционный суд запретил применять в России смертную казнь". lenta.ru.

- ^ a b c d e "Правовед - правовой ресурс Русецкого Александра Смертная казнь (правовое регулирование)". rusetsky.com. Archived from the original on November 3, 2005.

- ^ "Екатерина II Великая: Статьи: Императрица Екатерина II и ее "Наказ"". bnd.ru. Archived from the original on 2007-08-15.

- ^ a b c "Army soul of Russia". krotov.info. Archived from the original on May 10, 2009.

- ^ Administrator. "Смертная казнь в СССР в 1937-1938 гг". stalinism.ru.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Письмо Генерального прокурора СССР Р.А. Руденко, Министра внутренних дел СССР С.Н. Круглова и Министра юстиции СССР К.П. Горшенина 1-му секретарю ЦК КПСС Н.С. Хрущеву о пересмотре дел на осужденных за контрреволюционные преступления. Реабилитация: как это было. Документы Президиума ЦК КПСС и другие материалы. В 3-х томах. Vol. 1. pp. 103-105.

- ^ Peter Hodgkinson and William A. Schabas, Capital Punishment: Strategies for Abolition (Cambridge University Press, 2004) p274

- ^ The Soviet Penal System in the USSR and the SBZ/GDR Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ ф.А385. ВЕРХОВНЫЙ СОВЕТ РСФСР. оп.39. Дела по ходатайствам о помиловании осужденных к высшей мере наказания за 1978-1985 гг., retrieved 2013-6-8

- ^ "Woman who executed 1,500 people in WWII faced death sentence in 30 years". English Pravda.ru.

- ^ "Глава 2. Права и свободы человека и гражданина - Конституция Российской Федерации". constitution.ru.

- ^ "Уголовный кодекс Российской Федерации". Archived from the original on November 11, 2006.

- ^ "ИСПОЛНЕНИЕ НАКАЗАНИЯ В ВИДЕ СМЕРТНОЙ КАЗНИ - Уголовно-исполнительный кодекс РФ (УИК РФ) от 08.01.1997 N 1-ФЗ (Russian Federation Penal Execution Code DTD January 8, 1997, article 186) \ Консультант Плюс". consultant.ru. 29 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Домен tanatos.ru продаётся. Цена: 50 000,00 р." www.reg.ru.

- ^ a b c "7 МЕСЯЦЕВ ДО СМЕРТНОЙ КАЗНИ". Новая Газета. Archived from the original on 2008-09-04. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ^ "Госдума отсрочила введение смертной казни в России". lenta.ru.

- ^ a b c Сергей Подосенов, Более половины россиян за возвращение смертной казни, 1 июля 2013

- ^ Lenta.ru: В России: Три четверти россиян поддерживают смертную казнь, retrieved 2013-8-6

- ^ Россияне хотят вернуть смертную казнь - опрос Archived 2012-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, 29.03.2012, retrieved 2013-8-6

- ^ "54 percent of Russians want return of capital punishment, survey says - UPI.com". UPI.

- ^ "Death penalty moratorium will never be lifted – Russian ombudsman". RT International.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation

- ^ ""31 спорный вопрос" по истории: о пытках и казнях в эпоху опричнины: Наука и техника: Lenta.ru". lenta.ru.

- ^ "Соборное уложение 1649г. - Электронная Библиотека истории права". gumer.info.

- ^ "Смертная казнь в Российской империи: казнить, нельзя помиловать!". maxpark.com.

- ^ "Текст статьи "История телесных наказаний в русском уголовном праве" // Право России // ALLPRAVO.RU". allpravo.ru.

- ^ a b "Как казнили в СССР. Интервью с палачом". index.org.ru.

- ^ "Ъ-Власть - "Я расстреливал преступников, а не мирное население"". kommersant.ru.

- ^ "Исполнители смертных приговоров расстреливали убийц и выпивали по 100 грамм за упокой". segodnya.ua.

- ^ a b "Как проводится смертная казнь в Белоруссии?". Пикабу.

- ^ "2yxa.ru - Казни и Пытки, Ритуалы смертной казни". 2yxa.ru.

- ^ "Репортаж: Бессмертная казнь". rusrep.ru.

- ^ "Russian Federation Penal Code Article 186.4".

External links

- Russia: Death Penalty Worldwide Academic research database on the laws, practice, and statistics of capital punishment for every death penalty country in the world.