Public opinion on climate change

Public opinion on global warming is the aggregate of attitudes or beliefs held by the adult population concerning the science, economics, and politics of global warming. It is affected by media coverage of climate change.

Influences on individual opinion

Geographic region

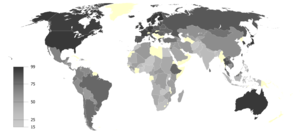

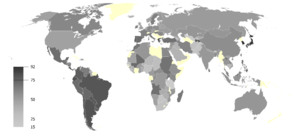

A 2007–2008 Gallup Poll surveyed individuals in 128 countries. This poll queried whether the respondent knew of global warming. Those who had a basic concept of global warming didn’t necessarily connect it to human activities, revealing that knowledge of global warming and the knowledge that it’s human-induced are two separate things. Over a third of the world's population were unaware of global warming. Developing countries have less awareness than developed, and Africa the least aware. Of those aware, residents of Latin America and developed countries in Asia led the belief that climate change is a result of human activities while Africa, parts of Asia and the Middle East, and a few countries from the former Soviet Union led in the opposite. Opinion within the United Kingdom was divided.[1]

The first major worldwide poll, conducted by Gallup in 2008–2009 in 127 countries, found that some 62% of people worldwide said they knew about global warming. In the industrialized countries of North America, Europe, and Japan, 67% or more knew about it (97% in the U.S., 99% in Japan); in developing countries, especially in Africa, fewer than a quarter knew about it, although many had noticed local weather changes. Among those who knew about global warming, there was a wide variation between nations in belief that the warming was a result of human activities.[2]

Adults in Asia, with the exception of those in developed countries, are the least likely to perceive global warming as a threat. In the western world, individuals are the most likely to be aware and perceive it as a very or somewhat serious threat to themselves and their families;[3] although Europeans are more concerned about climate change than those in the United States.[4] However, the public in Africa, where individuals are the most vulnerable to global warming while producing the least carbon dioxide, is the least aware – which translates into a low perception that it is a threat.[3]

These variations pose a challenge to policymakers, as different countries travel down different paths, making an agreement over an appropriate response difficult. While Africa may be the most vulnerable and produce the least amount of greenhouse gases, they are the most ambivalent. The top five emitters (China, the United States, India, Russia, and Japan), who together emit half the world's greenhouse gases, vary in both awareness and concern. The United States, Russia, and Japan are the most aware at over 85% of the population. Conversely, only two-thirds of people in China and one-third in India are aware. Japan expresses the greatest concern, which translates into support for environmental policies. People in China, Russia, and the United States, while varying in awareness, have expressed a similar proportion of aware individuals concerned. Similarly, those aware in India are likely to be concerned, but India faces challenges spreading this concern to the remaining population as its energy needs increase over the next decade.[5]

An online survey on environmental questions conducted in 20 countries by Ipsos MORI, "Global Trends 2014", shows broad agreement, especially on climate change and if it is caused by humans, though the U.S. ranked lowest with 54% agreement.[6] It has been suggested that the low U.S. ranking is tied to denial campaigns.[7]

A 2010 survey of 14 industrialized countries found that skepticism about the danger of global warming was highest in Australia, Norway, New Zealand and the United States, in that order, correlating positively with per capita emissions of carbon dioxide.[8]

United States

In 2009 Yale University conducted a study identifying global warming's "Six Americas". The report identifies six audiences with different opinions about global warming: The alarmed (18%), the concerned (33%), the cautious (19%), the disengaged (12%), the doubtful (11%) and the dismissive (7%). The alarmed and concerned make out the largest percentage and think something should be done about global warming. The cautious, disengaged and doubtful are less likely to take action. The dismissive are convinced global warming is not happening. These audiences can be used to define the best approaches for environmental action. The theory of the 'Six Americas' is also used for marketing purposes.[9]

Opinions in the United States vary intensely enough to be considered a culture war.[10][11]

In a January 2013 survey, Pew found that 69% of Americans say there is solid evidence that the Earth's average temperature has gotten warmer over the past few decades, up six points since November 2011 and 12 points since 2009.[12]

A Gallup poll in 2014 concluded that 51 percent of Americans were a little or not at all worried about climate change, 24 percent a great deal and 25 percent a fair amount.[13]

In 2015, 32 percent or Americans were worried about global warming as a great deal, 37 percent in 2016, and 45 percent in 2017. A poll taken in 2016 shows that 52% of Americans believe climate change to be caused by human activity, while 34% state it is caused by natural changes.[14] Data is increasingly showing that 62 percent of Americans believe that the effects of global warming are happening now in 2017.[15]

In 2016 GALLUP found that 64% of Americans are worried about global warming, 59% believed that global warming is already happening and 65% is convinced that global warming is caused by human activities. These numbers show that awareness of global warming is increasing in the United States[16]

In 2019 GALLUP found that one-third of Americans blame unusual winter temperatures on climate change.[17]

In 2019 the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication found that 69% of Americans believe that climate change is happening. Additionally, their research also found that Americans think that only 54% of the country believes that climate change is happening. These figures show that there is a disconnect between perceived public perception of the issue and reality.[18]

Education

In countries varying in awareness, an educational gap translates into a gap in awareness.[19] However an increase in awareness does not always result in an increase in perceived threat. In China, 98% of those who have completed four years or more of college education reported knowing something or a great deal of climate change while only 63% of those who have completed nine years of education reported the same. Despite the differences in awareness in China, all groups perceive a low level of threat from global warming. In India, those who are educated are more likely to be aware, and those who are educated there are far more likely to report perceiving global warming as a threat than those who are not educated.[5] In Europe, individuals who have attained a higher level of education perceive climate change as a serious threat. There is also a strong association between education and Internet use. Europeans who use the Internet more are more likely to perceive climate change as a serious threat.[20] However, a survey of American adults found "little disagreement among culturally diverse citizens[clarification needed] on what science knows about climate change.

Demographics

Residential demographics affect perceptions of global warming. In China, 77% of those who live in urban areas are aware of global warming compared to 52% in rural areas. This trend is mirrored in India with 49% to 29% awareness, respectively.[5]

Of the countries where at least half the population is aware of global warming, those with the majority who believe that global warming is due to human activities have a greater national GDP per unit energy—or, a greater energy efficiency.[21]

In Europe, individuals under fifty-five are more likely to perceive both "poverty, lack of food and drinking water" and climate change as a serious threat than individuals over fifty-five. Male individuals are more likely to perceive climate change as a threat than female individuals. Managers, white-collar workers, and students are more likely to perceive climate change as a greater threat than house persons and retired individuals.[20]

In the United States, conservative white men are more likely than other Americans to deny climate change.[22]

In Great Britain, a movement of by women known as "birthstrikers" advocates for refraining from procreation until the possibility of "climate breakdown and civilisation collapse" is averted.[23]

Political identification

In the United States, support for environmental protection was relatively non-partisan in the twentieth century. Republican Theodore Roosevelt established national parks whereas Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt established the Soil Conservation Service. Republican Richard Nixon was instrumental in founding the United States Environmental Protection Agency, and tried to install a third pillar of NATO dealing with environmental challenges such as acid rain and the greenhouse effect. Daniel Patrick Moynihan was Nixon's NATO delegate for the topic.[24]

This non-partisanship began to erode during the 1980s, when the Reagan administration described environmental protection as an economic burden. Views over global warming began to seriously diverge between Democrats and Republicans during the negotiations that led up to the creation of the Kyoto Protocol in 1998. In a 2008 Gallup poll of the American public, 76% of Democrats and only 41% of Republicans said that they believed global warming was already happening. The opinions of the political elites, such as members of Congress, tends to be even more polarized.[25]

Public opinion on climate change can be influenced by who people vote for. Although media coverage influences how some view climate change, research shows that voting behavior influences climate change skepticism. This shows that people’s views on climate change tend to align with the people they voted for.[26]

In Europe, opinion is not strongly divided among left and right parties. Although European political parties on the left, including Green parties, strongly support measures to address climate change, conservative European political parties maintain similar sentiments, most notably in Western and Northern Europe. For example, Margaret Thatcher, never a friend of the coal mining industry, was a strong supporter of an active climate protection policy and was instrumental in founding the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the British Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research.[27] Some speeches, as to the Royal Society on 27 September 1988[28] and to the UN general assembly in November 1989 helped to put climate change, acid rain, and general pollution in the British mainstream. After her career, however, Thatcher was less of a climate activist, as she called climate action a "marvelous excuse for supranational socialism", and called Al Gore an "apocalyptic hyperbole".[29] France's center-right President Chirac pushed key environmental and climate change policies in France in 2005–2007. Conservative German administrations (under the Christian Democratic Union and Christian Social Union) in the past two decades[when?] have supported European Union climate change initiatives; concern about forest dieback and acid rain regulation were initiated under Kohl's archconservative minister of the interior Friedrich Zimmermann. In the period after former President George W. Bush announced that the United States was leaving the Kyoto Treaty, European media and newspapers on both the left and right criticized the move. The conservative Spanish La Razón, the Irish Times, the Irish Independent, the Danish Berlingske Tidende, and the Greek Kathimerini all condemned the Bush administration's decision, as did left-leaning newspapers.[30]

In Norway, a 2013 poll conducted by TNS Gallup found that 92% of those who vote for the Socialist Left Party and 89% of those who vote for the Liberal Party believe that global warming is caused by humans, while the percentage who held this belief is 60% among voters for the Conservative Party and 41% among voters for the Progress Party.[31]

The shared sentiments between the political left and right on climate change further illustrate the divide in perception between the United States and Europe on climate change. As an example, conservative German Prime Ministers Helmut Kohl and Angela Merkel have differed with other parties in Germany only on how to meet emissions reduction targets, not whether or not to establish or fulfill them.[30]

A 2017 study found that those who changed their opinion on climate change between 2010 and 2014 did so "primarily to align better with those who shared their party identification and political ideology. This conforms with the theory of motivated reasoning: Evidence consistent with prior beliefs is viewed as strong and, on politically salient issues, people strive to bring their opinions into conformance with those who share their political identity".[32] Furthermore, a 2019 study examining the growing skepticism of climate change among American Republicans argues that persuasion and rhetoric from party elites play a critical role in public opinion formation, and that these elite cues are propagated through mainstream and social media sources.[33]

For those who care about the environment and want change are not happy about some policies, for example the support of the cap and trade policy but very few people are willing to pay more than 15 dollars per month for a program that is supposed to help the environment. There is evidence that not many people are aware of climate change in the US, only 2% of respondents ranked the environment as the top issue in the US.[34]

Individual risk assessment and assignment

The IPCC attempts to orchestrate global (climate) change research to shape a worldwide consensus.[35] However, the consensus approach has been dubbed more a liability than an asset in comparison to other environmental challenges.[36][37] The linear model of policy-making, based on a more knowledge we have, the better the political response will be is said to have not been working and is in the meantime rejected by sociology.[38]

Sheldon Ungar, a Canadian sociologist, compares the different public reactions towards ozone depletion and global warming.[39] The public opinion failed to tie climate change to concrete events which could be used as a threshold or beacon to signify immediate danger.[39] Scientific predictions of a temperature rise of two to three degrees Celsius over several decades do not respond with people, e.g. in North America, that experience similar swings during a single day.[39] As scientists define global warming a problem of the future, a liability in "attention economy", pessimistic outlooks in general and assigning extreme weather to climate change have often been discredited or ridiculed (compare Gore effect) in the public arena.[40] While the greenhouse effect per se is essential for life on earth, the case was quite different with the ozone shield and other metaphors about the ozone depletion. The scientific assessment of the ozone problem also had large uncertainties. But the metaphors used in the discussion (ozone shield, ozone hole) reflected better with lay people and their concerns.

The idea of rays penetrating a damaged "shield" meshes nicely with abiding and resonant cultural motifs, including "Hollywood affinities". These range from the shields on the Starship Enterprise to Star Wars, ... It is these pre-scientific bridging metaphors built around the penetration of a deteriorating shield that render the ozone problem relatively simple. That the ozone threat can be linked with Darth Vader means that it is encompassed in common sense understandings that are deeply ingrained and widely shared. (Sheldon Ungar 2000)[39]

The chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) regulation attempts of the end of the 1980s profited from those easy-to-grasp metaphors and the personal risk assumptions taken from them. As well the fate of celebrities like President Ronald Reagan, which had skin cancer removal in 1985 and 1987, was of high importance. In case of the public opinion on climate change, no imminent danger is perceived.[39]

Ideology

In the United States, ideology is an effective predictor of party identification, where conservatives are more prevalent among Republicans, and moderates and liberals among independents and Democrats.[41] A shift in ideology is often associated with in a shift in political views.[42] For example, when the number of conservatives rose from 2008 to 2009, the number of individuals who felt that global warming was being exaggerated in the media also rose.[43] The 2006 BBC World Service poll found that when asked about various policy options to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – tax incentives for alternative energy research and development, installment of taxes to encourage energy conservation, and reliance on nuclear energy to reduce fossil fuels. The majority of those asked felt that tax incentives were the path of action that they preferred.

As of May 2016, polls have repeatedly found that a majority of Republican voters, particularly young ones, believe the government should take action to reduce carbon dioxide emissions.[44]

The pursuit of green energy is an ideology that defines hydroelectric dams,[45] natural gas power plants and nuclear power as unacceptable alternative energies for the eight billion tons of coal burnt each year. While there is popular support for wind, solar, biomass, and geothermal energy, all these sources combined only supplied 1.3% of global energy in 2013.[46][47]

After a country host the annual Conference of the Parties (COP) climate legislation increases which causes policy diffusion. There is strong evidence of policy diffusion which is when a policy is made it is influenced by the policy choices made elsewhere.This can a have positive effect on climate legislation.[48]

Charts

A 2018 study found that individuals were more likely to accept that global temperatures were increasing if they were shown the information in a chart rather than in text.[49][50]

Issues

Science

A scientific consensus on climate change exists, as recognized by national academies of science and other authoritative bodies.[51] The opinion gap between scientists and the public in 2009 stands at 84% to 49% that global temperatures are increasing because of human-activity.[52] However, more recent research has identified substantial geographical variation in the public's understanding of the scientific consensus.[53]

Economics

Economic debates weigh the benefits of limiting industrial emissions of mitigating global warming against the costs that such changes would entail. While there is a greater amount of agreement over whether global warming exists, there is less agreement over the appropriate response. Electric or petroleum distribution may be government owned or utilities may be regulated by government. The government owned or regulated utilities may, or may not choose to make lower emissions a priority over economics, in unregulated counties industry follows economic priorities. An example of the economic priority is Royal Dutch Shell PLC reporting CO2 emissions of 81 million metric tonnes in 2013.[54]

Media

The popular media in the U.S. gives greater attention to skeptics relative to the scientific community as a whole, and the level of agreement within the scientific community has not been accurately communicated.[55][56] US popular media coverage differs from that presented in other countries, where reporting is more consistent with the scientific literature.[57] Some journalists attribute the difference to climate change denial being propagated, mainly in the US, by business-centered organizations employing tactics worked out previously by the US tobacco lobby.[58][59][60] However, one study suggests that these tactic are less prominent in the media and that the public instead draws their opinions on climate mainly from the cues of political party elites.[61]

The efforts of Al Gore and other environmental campaigns have focused on the effects of global warming and have managed to increase awareness and concern, but despite these efforts as of 2007, the number of Americans believing humans are the cause of global warming was holding steady at 61%, and those believing the popular media was understating the issue remained about 35%.[62] Between 2010 and 2013, the number of Americans who believe the media under-reports the seriousness of global warming has been increasing, and the number who think media over-states it has been falling. According to a 2013 Gallup US opinion poll, 57% believe global warming is at least as bad as portrayed in the media (with 33% thinking media has downplayed global warming and 24% saying coverage is accurate). Less than half of Americans (41%) think the problem is not as bad as media portrays it.[63]

September 2011 Angus Reid Public Opinion poll found that Britons (43%) are less likely than Americans (49%) or Canadians (52%) to say that "global warming is a fact and is mostly caused by emissions from vehicles and industrial facilities". The same poll found that 20% of Americans, 20% of Britons and 14% of Canadians think "global warming is a theory that has not yet been proven".[64]

A March 2013 Public Policy Polling poll about widespread and infamous conspiracy theories found that 37% of American voters believe that global warming is a hoax, while 51% do not.[65]

A 2013 poll in Norway conducted by TNS Gallup found that 66% of the population believe that climate change is caused by humans, while 17% do not believe this.[66]

Politics

Public opinion impacts on the issue of climate change because governments need willing electorates and citizens in order to implement policies that address climate change. Further, when climate change perceptions differ between the populace and governments, the communication of risk to the public becomes problematic. Finally, a public that is not aware of the issues surrounding climate change may resist or oppose climate change policies, which is of considerable importance to politicians and state leaders.[67]

Public support for action to forestall global warming is as strong as public support has been historically for many other government actions; however, it is not "intense" in the sense that it overrides other priorities.[67][68]

A 2009 Eurobarometer survey found that, on the average, Europeans rate climate change as the second most serious problem facing the world today, between "poverty, the lack of food and drinking water" and "a major global economic downturn." 87% of Europeans consider climate change to be a "serious" or "very serious" problem, while 10% "do not consider it a serious problem." However, the proportion who believe it to be a problem has dropped in the period 2008/9 when the surveys were conducted.[69] While the small majority believe climate change is a serious threat, 55% percent believe the EU is doing too little and 30% believe the EU is going the right amount.[70] As a result of European Union climate change perceptions, "climate change is an issue that has reached such a level of social and political acceptability across the EU that it enables (indeed, forces) the EU Commission and national leaders to produce all sorts of measures, including taxes."[30] Despite the persistent high level of personal involvement of European citizens, found in another Eurobarometer survey in 2011,[71] EU leaders have begun to downscale climate policy issues on the political agenda since the beginning of the Eurozone crisis.[72]

Although public opinion may not be the only factor influencing renewable energy policies, it is a key catalyst. Research has found that the shifts in public opinion in the direction of pro-environmentalism strongly increased the adoption of renewable energy policies in Europe, which can thus be applied in the U.S. and how important climate solutions are to Americans.[73]

The proportion of Americans who believe that the effects of global warming have begun or will begin in a few years rose to a peak in 2008 where it then declined, and a similar trend was found regarding the belief that global warming is a threat to their lifestyle within their lifetime.[74] Concern over global warming often corresponds with economic downturns and national crisis such as 9/11 as Americans prioritize the economy and national security over environmental concerns. However the drop in concern in 2008 is unique compared to other environmental issues.[43] Considered in the context of environmental issues, Americans consider global warming as a less critical concern than the pollution of rivers, lakes, and drinking water; toxic waste; fresh water needs; air pollution; damage to the ozone layer; and the loss of tropical rain forests. However, Americans prioritize global warming over species extinction and acid rain issues.[75] Since 2000 the partisan gap has grown as Republican and Democratic views diverge.[76]

See also

References

- ^ Pelham, Brett (22 April 2009). "Awareness, Opinions About Global Warming Vary Worldwide". The Gallup Organization. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ Pelham, Brett (2009). "Awareness, Opinions about Global Warming Vary Worldwide". Gallup. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ a b Pugliese, Anita; Ray, Julie (11 December 2009). "Awareness of Climate Change and Threat Vary by Region". Gallup. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ Crampton, Thomas (1 January 2007). "More in Europe worry about climate than in U.S., poll shows". International Herald Tribune. The New York Times. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ^ a b c Pugliese, Anita; Ray, Julie (7 December 2009). "Top-Emitting Countries Differ on Climate Change Threat". Gallup. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ Ipsos MORI. "Global Trends 2014". Archived from the original on 23 February 2015.

- ^ MotherJones (22 July 2014). "The Strange Relationship Between Global Warming Denial and…Speaking English".

- ^ Tranter, Bruce; Booth, Kate (July 2015). "Scepticism in a Changing Climate: A Cross-national Study". Global Environmental Change. 33: 54–164. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.05.003.

- ^ "Global Warming's Six Americas 2009". Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ Gillis, Justin (17 April 2012). "Americans Link Global Warming to Extreme Weather, Poll Says". The New York Times.

- ^ Climate Science as Culture War: The public debate around climate change is no longer about science – it’s about values, culture, and ideology Fall 2012 Stanford Social Innovation Review

- ^ Climate Change: Key Data Points from Pew Research | Pew Research Center

- ^ Riffkin, Rebecca (12 March 2014). "Climate Change Not a Top Worry in U.S." Gallup. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ "Yale Climate Opinion Maps - U.S. 2016 - Yale Program on Climate Change Communication". Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Inc., Gallup. "Global Warming Concern at Three-Decade High in U.S." Gallup.com. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Inc., Gallup. "U.S. Concern About Global Warming at Eight-Year High". Gallup.com. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Inc., Gallup. "One-Third in U.S. Blame Unusual Winter Temps on Climate Change". Gallup.com. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/americans-underestimate-how-many-others-in-the-u-s-think-global-warming-is-happening/

- ^ Closing the Massive Gaps Between Culture Awareness, Education, and Action

- ^ a b TNS Opinion and Social 2009, p. 13

- ^ Pelham, Brett W. (24 April 2009). "Views on Global Warming Relate to Energy Efficiency". Gallup. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ McCright, Aaron M.; Dunlap, Riley E. (October 2011). "Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States". Global Environmental Change. 21 (4): 1163–72. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003.

- ^ Hunt, Elle (12 March 2019). "BirthStrikers: meet the women who refuse to have children until climate change ends". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ Die Frühgeschichte der globalen Umweltkrise und die Formierung der deutschen Umweltpolitik(1950–1973) (Early history of the environmental crisis and the setup of German environmental policy 1950–1973), Kai F. Hünemörder, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2004 ISBN

- ^ Dunlap, Riley E. (29 May 2009). "Climate-Change Views: Republican-Democratic Gaps Expand". Gallup. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ McCrea, Rod; Leviston, Zoe; Walker, Iain A. (27 July 2016). "Climate Change Skepticism and Voting Behavior". Environment and Behavior. 48 (10): 1309–1334. doi:10.1177/0013916515599571.

- ^ How Margaret Thatcher Made the Conservative Case for Climate Action, James West, Mother Jones, Mon 8 April 2013

- ^ 1988 Sep 27 Tu Margaret Thatcher Speech to the Royal Society

- ^ An Inconvenient Truth About Margaret Thatcher: She Was a Climate Hawk, Will Oremus, Slate (magazine) 8 April 2013

- ^ a b c Schreurs, M. A.; Tiberghien, Y. (November 2007). "Multi-Level Reinforcement: Explaining European Union Leadership in Climate Change Mitigation" (Full free text). Global Environmental Politics. 7 (4): 19–46. doi:10.1162/glep.2007.7.4.19. ISSN 1526-3800.

- ^ "Among those who vote for the Liberal Party or the Socialist Party, the great majority think that humans are behind climate changes (89 and 92%). Only 41% of those who vote for the Progress Party agree, while the number for Conservative Party voters is 60%." (Translated from Norwegian to English) Liv Jorun Andenes and Amalie Kvame Holm: Typisk norsk å være klimaskeptisk Archived 8 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine (in Norwegian) Vårt Land, retrieved 8 July 2013

- ^ Palm, Risa; Lewis, Gregory B.; Feng, Bo (13 March 2017). "What Causes People to Change Their Opinion about Climate Change?". Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 0 (4): 883–896. doi:10.1080/24694452.2016.1270193. ISSN 2469-4452.

- ^ Merkley, Eric; Stecula, Dominik (8–9 November 2019). "Party Cues in the News: Elite Opinion Leadership and Climate Skepticism" (PDF). Toronto Political Behaviour Workshop: 1. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ Vandeweerdt, Clara; Kerremans, Bart; Cohn, Avery (26 November 2015). "Climate voting in the US Congress: the power of public concern". Environmental Politics. 25 (2): 268–288. doi:10.1080/09644016.2016.1116651.

- ^ [[Aant Elzinga]], ”Shaping Worldwide Consensus: the Orchestration of Global Change Research”, in Elzinga & Landström eds. (1996): 223–55. ISBN 0-947568-67-0.

- ^ "Environmental Politics Climate Change and Knowledge Politics" Archived 26 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Reiner Grundmann. Vol. 16, No. 3, 414–432, June 2007

- ^ Technische Problemlösung, Verhandeln und umfassende Problemlösung, (eng. technical trouble shooting, negotiating and generic problem solving capability) in Gesellschaftliche Komplexität und kollektive Handlungsfähigkeit (Societys complexity and collective ability to act), ed. Schimank, U. (2000). Frankfurt/Main: Campus, pp. 154–82 book summary at the Max Planck Gesellschaft Archived 12 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Grundmann, R. (2010). "Climate Change: What Role for Sociology?: A Response to Constance Lever-Tracy". Current Sociology. 58: 897–910. doi:10.1177/0011392110376031. see Lever-Tracy, Constance (2008). "Global Warming and Sociology". Current Sociology. 56: 445–466. doi:10.1177/0011392107088238.</

- ^ a b c d e Ungar, Sheldon (2000). Public Understanding of Science. 9: 297–312. doi:10.1088/0963-6625/9/3/306.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sheldon Ungar Climatic Change February 1999, Volume 41, Issue 2, pp. 133–150 Is Strange Weather in the Air? A Study of U.S. National Network News Coverage of Extreme Weather Events

- ^ Riley E. Dunlap; Aaron M. McCright; Jerrod H. Yarosh. "The Political Divide on Climate Change: Partisan Polarization Widens in the U.S." Environment (September–October 2016): 4–22. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Saad, Lydia (26 June 2009). "Conservatives Maintain Edge as Top Ideological Group". Gallup. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ a b Saad, Lydia (11 April 2009). "Increased Number Think Global Warming Is 'Exaggerated'". Gallup. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ Goode, Erica (20 May 2016). "What Are Donald Trump's Views on Climate Change? Some Clues Emerge". The New York Times.

- ^ Wockner, Gary (14 August 2014). "Dams Cause Climate Change, They Are Not Clean Energy". EcoWatch. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ "Nine out of 10 people want more renewable energy". The Guardian. 23 April 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ "Global Overview" (PDF). Renewables 2015: Global Status Report: 27–37. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2015.

- ^ Fankhauser, Samuel; Gennaioli, Caterina; Collins, Murray (3 March 2015). "Do international factors influence the passage of climate change legislation?" (PDF). Climate Policy. 16 (3): 318–331. doi:10.1080/14693062.2014.1000814.

- ^ "Analysis | Study: Charts change hearts and minds better than words do". Washington Post. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ Nyhan, Brendan; Reifler, Jason (2018). "The roles of information deficits and identity threat in the prevalence of misperceptions". Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. 29 (2): 222–244. doi:10.1080/17457289.2018.1465061. hdl:10871/32325.

- ^ Joint Science Academies (2005). "Joint science academies' statement: Global response to climate change" (Full free text). United States National Academies of Sciences. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- ^ "Public Praises Science; Scientists Fault Public, Media" (PDF). Pew Research Center. 9 June 2009. pp. 5, 55. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Zhang, Baobao; van der Linden, Sander; Mildenberger, Matto; Marlon, Jennifer; Howe, Peter; Leiserowitz, Anthony (2018). "Experimental effects of climate messages vary geographically". Nature Climate Change. 21 (5): 370–374. Bibcode:2018NatCC...8..370Z. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0122-0.

- ^ "Royal Dutch Shell PLC – AMEE".

- ^ Boykoff, M.; Boykoff, J. (July 2004). "Balance as bias: global warming and the US prestige press" (PDF). Global Environmental Change Part A. 14 (2): 125–36. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2003.10.001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ Antilla, L. (2005). "Climate of scepticism: US newspaper coverage of the science of climate change". Global Environmental Change Part A. 15 (4): 338–52. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.372.2033. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.08.003.

- ^ Dispensa, J. M.; Brulle, R. J. (2003). "Media's social construction of environmental issues: focus on global warming – a comparative study" (PDF). International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 23 (10): 74. doi:10.1108/01443330310790327. Archived from the original (Full free text) on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- ^ Begley, Sharon (13 August 2007). "The Truth About Denial". Newsweek. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ David, Adam (20 September 2006). "Royal Society tells Exxon: stop funding climate change denial". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ Sandell, Clayton (3 January 2007). "Report: Big Money Confusing Public on Global Warming". ABC News. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ Merkley, Eric; Stecula, Dominik A. (20 March 2018). "Party Elites or Manufactured Doubt? The Informational Context of Climate Change Polarization". Science Communication. 40 (2): 258–274. doi:10.1177/1075547018760334.

- ^ Saad, Lydia (21 March 2007). "Did Hollywood's Glare Heat Up Public Concern About Global Warming?". Gallup. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ Saad, Lydia. "Americans' Concerns About Global Warming on the Rise".

- ^ [1]Angus Reid Public Opinion poll conducted 25 August through 2 September 2011 Archived 15 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Williams, Jim (2 April 2013). "Conspiracy Theory Poll Results". Public Policy Polling. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ (Translated from Norwegian to English) "Two of three believe climate change is caused by humans. I believe that climate change is caused by humans (n=1001) Percentage that fully agree or disagree: (graph that shows numbers from 2009 to 2013, with 66/17 in 2013.")Presentasjon av resultater fra TNS Gallups Klimabarometer 2013 (7 June 2013): Klimasak avgjør for hver fjerde velger (in Norwegian) (link to pdf, p. 29), TNS Gallup, retrieved 8 July 2013

- ^ a b Lorenzoni, I.; Pidgeon, N. F. (2006). "Public Views on Climate Change: European and USA Perspectives" (Full free text). Climatic Change. 77 (1–2): 73–95. Bibcode:2006ClCh...77...73L. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9072-z. ISSN 1573-1480."Despite the relatively high concern levels detected in these surveys, the importance of climate change is secondary in relation to other environmental, personal and social issues." 15 November 2005, accessed 27 April 2015

- ^ Roger Pielke, Jr. (28 September 2010). The Climate Fix: What Scientists and Politicians Won't Tell You About Global Warming (hardcover). Basic Books. pp. 36–46. ISBN 978-0465020522.

...climate change does not rank high as a public priority in the context of the full spectrum of policy issues.

- ^ TNS Opinion and Social 2009, p. 15

- ^ TNS Opinion and Social 2009, p. 21

- ^ European Commission, Special Eurobarometer 372 – Climate Change Brussels, June 2011

- ^ Oliver Geden (2012), The End of Climate Policy as We Knew it, SWP Research Paper 2012/RP01

- ^ Anderson, Brilé; Böhmelt, Tobias; Ward, Hugh (1 November 2017). "Public opinion and environmental policy output: a cross-national analysis of energy policies in Europe". Environmental Research Letters. 12 (11): 114011. Bibcode:2017ERL....12k4011A. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aa8f80.

- ^ Newport, Frank (11 March 2010). "Americans' Global Warming Concerns Continue to Drop". Gallup. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ Saad, Lydia (7 April 2006). "Americans Still Not Highly Concerned About Global Warming". Gallup. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ Dunlap, Riley E. (29 May 2008). "Partisan Gap on Global Warming Grows". Gallup Organization. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

Bibliography

- TNS Opinion and Social (December 2009). "Europeans' Attitudes Towards Climate Change" (Full free text). European Commission. Retrieved 24 December 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)