Melancholia (2011 film)

| Melancholia | |

|---|---|

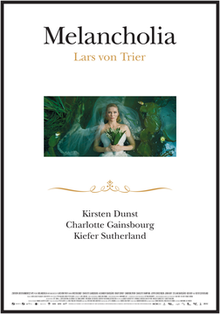

Danish theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Lars von Trier |

| Written by | Lars von Trier |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Manuel Alberto Claro |

| Edited by | Molly Malene Stensgaard |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 135 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $9.4 million[2] (c. US$9.4 million (2010)) |

| Box office | $21.8 million[3][4] |

Melancholia is a 2011 science fiction drama film written and directed by Lars von Trier and starring Kirsten Dunst, Charlotte Gainsbourg, and Kiefer Sutherland, with Alexander Skarsgård, Brady Corbet, Cameron Spurr, Charlotte Rampling, Jesper Christensen, John Hurt, Stellan Skarsgård, and Udo Kier in supporting roles. The film's story revolves around two sisters, one of whom is preparing to marry just before a rogue planet is about to collide with Earth.

Von Trier's initial inspiration for the film came from a depressive episode he suffered. The film is a Danish production by Zentropa, with international co-producers in Sweden, France, Germany and Italy.[5][6] Filming took place in Sweden. Melancholia prominently features music from the prelude to Richard Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde (1857–1859). It is the second entry in von Trier's unofficially titled "Depression Trilogy", preceded by Antichrist and followed by Nymphomaniac.[7]

Melancholia premiered 18 May 2011 at the 64th Cannes Film Festival, where it was critically lauded. Dunst received the festival's Best Actress Award for her performance, which was a common area of praise among critics. Although it has detractors, many critics and film scholars have considered the film to be a personal masterpiece, and one of the best films of 2011.[8]

Plot

The film begins with an introductory sequence involving the main characters and images from space.[9] These virtually still images reveal the key elements of the film: Justine the bride in deep melancholy with birds falling behind her; of a lawn with trees and sundial with two different shadows; Pieter Brueghel's The Hunters in the Snow burning; the black horse collapsing in slow motion; Justine as a bride being swept along by a river; her wedding dress tangled in plant matter; and finally Justine and her nephew building their magic cave before Melancholia crashes into Earth.

Part One: "Justine"

Delayed by their stretch limousine's difficulty traversing the narrow winding rural road, newlyweds Justine and Michael arrive two hours late for their own wedding reception at the estate of Justine's sister, Claire, and her husband, John. Justine has a dysfunctional family: brother-in-law John appears to resent having to pay for the wedding; father Dexter is hedonistic and selfish to the point of narcissism, while mother Gaby is brutally jaded, her outspokenness leading John to throw her out of the house. No one ever asks what Justine wants, or why she is unhappy, but throughout the dinner she is praised for being beautiful. Claire urges Justine to hide her debilitating melancholy from her new husband Michael. Justine flees the wedding reception in a golf cart. Frustrated by excessive fabric, she tears her dress getting out of the cart. At the eighteenth hole of the golf course on the estate, she looks up at the night sky, squatting to urinate on the hole.

Justine's boss, Jack, is ruthless, greedy, and gluttonous. During his wedding speech, he's hustling Justine to meet a work deadline (she writes copy). He pushes her throughout the evening to create a tagline to promote a campaign based on a modern facsimile of Pieter Bruegel the Elder's The Land of Cockaigne (the mythical land of excess). She later opens an art book, only to find this same painting. Delaying the cutting of the wedding cake, Justine and Gaby independently escape to take baths.

Justine's boss's nephew, Tim, is given the chance to exploit the opportunity to get the tagline at all costs in order to promote his career: a task similar to what Justine was previously so successful at. He reluctantly, but doggedly, pursues Justine throughout the wedding reception. She cannot consummate her marriage with her husband and eventually goes out onto a sand trap and has sex with Tim. Unable to get the tagline from Justine, Tim is later fired for his "professional" failure, but Justine also resigns, telling Jack that he is a "despicable, power-hungry little man." After several hours of being alienated from each other, Justine and Michael quietly agree to call off the marriage. Michael departs. Early the following morning, while horseback riding with Claire, Justine notices Antares is no longer visible in the sky.

Part Two: "Claire"

Later, the reason for Antares's disappearance has become public knowledge: a newly discovered rogue planet called Melancholia, which entered the Solar System from behind the Sun, was blocking the star from view. The planet has now become visible in the sky as it approaches ever closer to Earth. John is excited about the "fly-by" predicted by scientists, while Claire is frightened by alternate predictions of Earth being hit.

In the meantime, Justine's depression has grown worse. She is placed in the care of Claire and John. Justine is essentially catatonic and Claire is unable to help her, even to assist her into the bath. In an effort to cheer her up, Claire makes meatloaf. Justine admits that she is so numb that even her favourite meal tastes of ash.

As Justine is forced into waking patterns, her connection to her beloved black horse Abraham becomes remote and frustrating. On two occasions, the horse refuses to cross a bridge over a river. Justine acts brutally towards the horse and eventually whips him mercilessly to the ground.

Meanwhile, Claire is fearful that the end of the world is imminent, despite her husband's assurances. She searches the Internet and finds an article predicting that Melancholia and Earth will, in fact, collide. Her husband assures her that these anecdotes are written by "prophets of doom" looking for their 15 minutes of fame. Claire tries to relax. The next day, a somewhat-healthier Justine confesses to Claire that she simply "knows" certain things—like the number of beans in the bottle at her wedding reception and that Earth and Melancholia will actually destroy each other. What's more, Justine says: this is a good thing because the Earth is evil.

That night, Melancholia passes Earth, as predicted by the scientists (to great relief). However, the next day Claire realizes (when using a circular device made by her son) that Melancholia is actually getting bigger and circling back—as predicted by the Internet article. She begins to panic. She looks for John, only to find him dead in the stables (he purposefully overdosed on pills Claire was saving). Claire, realizing Melancholia's impending arrival, releases Abraham. Later when Justine asks where John is, Claire says that he has ridden into the village with Abraham.

Claire calls the rest of her family together for a completely typical breakfast. Justine, noticing John's absence, questions Claire's intentions. Suddenly, as a result of Melancholia's proximity to Earth, a hailstorm starts. A panicked Claire tries to escape the estate with her son, but the cars will not start, and the golf cart shuts down as she attempts to cross the same bridge that Justine had attempted earlier. Returning to the mansion, Claire tries to accept the inevitable. In a private conversation with Justine, Claire suggests that their last act be coming together on the terrace with wine and music. Justine crassly dismisses her idea.

Having noticed that Abraham is wandering around the estate without any sign of his father, Claire's son, Leo, is frightened. "Dad said there's nothing to do, nowhere to hide," Leo says, aware of Melancholia's closeness. He is reassured by Justine, who says that they can be safe in a "magic cave", something she had promised to build several times throughout the film. They gather tree sticks to build the cave in the form of a teepee without canvas.

The "magic cave" stands in the middle of a field on the golf course. Leo, Justine, and Claire sit in the teepee, holding hands as the final storm begins. Leo believes in the magic cave and closes his eyes. Claire is terrified and cries profusely. Justine watches them both, and accepts her fate calmly and stoically. In the last shot Claire shudders, Leo and Justine sit in meditative posture as Melancholia fills the sky behind the teepee, then a wall of fire passes through the field as the planets collide, killing them as a result of the firestorm. The sounds of the destruction of both planets echo and rumble while the screen fades to black.

Cast

- Kirsten Dunst as Justine

- Charlotte Gainsbourg as Claire

- Alexander Skarsgård as Michael

- Kiefer Sutherland as John, Claire's husband

- Cameron Spurr as Leo

- Charlotte Rampling as Gaby, Justine and Claire's mother

- John Hurt as Dexter, Justine and Claire's father

- Jesper Christensen as Little Father, The Butler

- Stellan Skarsgård as Jack, Justine's boss

- Brady Corbet as Tim

- Udo Kier as The Wedding Planner

Production

Development

The idea for the film originated during a therapy session Lars von Trier attended during treatments for his depression. A therapist had told von Trier that depressive people tend to act more calmly than others under heavy pressure, because they already expect bad things to happen. Von Trier then developed the story not primarily as a disaster film, and without any ambition to portray astrophysics realistically, but as a way to examine the human psyche during a disaster.[10][11]

"In a James Bond movie we expect the hero to survive. It can get exciting nonetheless. And some things may be thrilling precisely because we know what's going to happen, but not how they will happen. In Melancholia it's interesting to see how the characters we follow react as the planet approaches Earth."

Trier on his decision to reveal the ending in the beginning of the film[12]

The idea of a planetary collision was inspired by websites with theories about such events. Von Trier decided from the outset that it would be clear from the beginning that the world would actually end in the film, so audiences would not be distracted by the suspense of not knowing. The concept of the two sisters as main characters developed via an exchange of letters between von Trier and the Spanish actress Penélope Cruz. Cruz wrote that she would like to work with von Trier, and spoke enthusiastically about the play The Maids by Jean Genet. As von Trier subsequently tried to write a role for the actress, the two maids from the play evolved into the sisters Justine and Claire in Melancholia. Much of the personality of the character Justine was based on von Trier himself.[12] The name was inspired by the 1791 novel Justine by the Marquis de Sade.[13]

Melancholia was produced by Denmark's Zentropa, with co-production support from its subsidiary in Germany, Sweden's Memfis Film, France's Slot Machine and Liberator Productions.[14] The production received 7.9 million Danish kroner from the Danish Film Institute, 600,000 euro from Eurimages and 3 million Swedish kronor from the Swedish Film Institute.[15][16] Additional funding was provided by Film i Väst, DR, Arte France, CNC, Canal+, BIM Italy, Filmstiftung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Sveriges Television and Nordisk Film & TV-Fond.[14] The total budget was 52.5 million Danish kroner.[2]

Cruz was initially expected to play the lead role, but dropped out when the filming schedule of another project was changed. Von Trier then offered the role to Kirsten Dunst, who accepted it. Dunst had been suggested for the role by the American filmmaker Paul Thomas Anderson in a discussion about the film between him and von Trier.[12][13]

Filming

Principal photography began 22 July and ended 8 September 2010. Interior scenes were shot at Film i Väst's studios in Trollhättan, Sweden. It was the fourth time Trier made a film in Trollhättan.[17] Exteriors included the area surrounding the Tjolöholm Castle.[18] The film was recorded digitally with Arri Alexa and Phantom cameras.[19] Trier employed his usual directing style with no rehearsals; instead the actors improvised and received instructions between the takes.[17] The camera was initially operated by Trier, and then left to cinematographer Manuel Alberto Claro who repeated Trier's movements. Claro said about the method: "[von Trier] wants to experience the situations the first time. He finds an energy in the scenes, presence, and makes up with the photographic aesthetics."[2] Trier explained that the visual style he aimed at in Melancholia was "a clash between what is romantic and grand and stylized and then some form of reality", which he hoped to achieve through the hand-held camerawork.[12] He feared however that it would tilt too much toward the romantic, because of the setting at the upscale wedding, and the castle, which he called "super kitschy".[12][18]

Post-production

The prelude to Richard Wagner's Tristan und Isolde supplies the main musical theme of the film, and Trier's use of an overture-like opening sequence before the first act is a technique closely associated with Wagner. This choice was inspired by a 30-page section of Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time, where Proust concludes that Wagner's prelude is the greatest work of art of all time. Melancholia uses music more than any film by Trier since The Element of Crime from 1984. In some scenes, the film was edited in the same pace as the music. Trier said: "It's kind of like a music video that way. It's supposed to be vulgar."[10] Trier also pointed out parallels between both the film's usage of Wagner and the film's editing to the music and the aesthetics of Nazi Germany.[10]

Visual effects were provided by companies in Poland, Germany and Sweden under visual effects supervisor Peter Hjorth. Poland's Platige Image, which previously had worked with Trier on Antichrist, created most of the effects seen in the film's opening sequence; the earliest instructions were provided by Trier in the summer 2010, after which a team of 19 visual effects artists worked on the project for three months.[20]

Release

In his director's statement, Trier wrote that he had started to regret having made such a polished film, but that he hoped it would contain some flaws which would make it interesting. The director wrote: "I desired to dive headlong into the abyss of German romanticism ... But is that not just another way of expressing defeat? Defeat to the lowest of cinematic common denominators? Romance is abused in all sorts of endlessly dull ways in mainstream products."[21]

The premiere took place at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival, where Melancholia was screened in competition on 18 May.[22] The press conference after the screening gained considerable publicity. The Hollywood Reporter's Scott Roxborough wrote that "Von Trier has never been very P.C. and his Cannes press conferences always play like a dark stand-up routine, but at the Melancholia press conference he took it to another level, tossing a grenade into any sense of public decorum."[23] Trier first joked about working on a hardcore pornographic film that would star Dunst and Gainsbourg.[24] When asked about the relation between the influences of German Romanticism in Melancholia and Trier's own German heritage, the director brought up that he had been raised believing his biological father was a Jew, only to learn as an adult that his actual father was a German. He then made jokes about Jews and Nazis, said he understood Adolf Hitler and admired the work of architect Albert Speer, and jokingly announced that he was a Nazi.[23][25] The Cannes Film Festival issued an official apology for the remarks the same day and clarified that Trier is not a Nazi or an anti-Semite, then declared the director "persona non grata" the following day.[26][27] This meant he was not allowed to go within 100 meters of the Festival Palace, but he did remain in Cannes and continued to give promotional interviews.[28]

The film was released in Denmark on 26 May 2011 through Nordisk Film.[14] Launched on 57 screens, the film entered the box-office chart as number three.[29] A total of 50,000 tickets were eventually sold in Denmark.[30] It was released in the United Kingdom and Ireland on 30 September, in Germany on 6 October and in Italy on 21 October.[31] Magnolia Pictures acquired the distribution rights for North America and it was released on 11 November, with a pre-theatrical release on 13 October as a rental through such Direct TV vendors as Vudu and Amazon.com.[31][32] Madman Entertainment bought the rights for Australia and New Zealand.[33]

Reception

Critical response

Melancholia received positive reviews from critics. The film holds a 80% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 200 reviews, with an average rating of 7.39/10. The website's critical consensus states, "Melancholia's dramatic tricks are more obvious than they should be, but this is otherwise a showcase for Kirsten Dunst's acting and for Lars von Trier's profound, visceral vision of depression and destruction."[34] The film also holds a score of 80 out of 100 on Metacritic, based on 40 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews."[35] A 2017 data analysis of Metacritic reviews by Gizmodo UK found the film to be the most critically divisive film of recent years.[36]

Kim Skotte of Politiken wrote that "there are images—many images—in Melancholia which underline that Lars von Trier is a unique film storyteller", and "the choice of material and treatment of it underlines Lars von Trier's originality." Skotte also compared it to the director's previous film: "Through its material and look, Melancholia creates rifts, but unlike Antichrist I don't feel that there is a fence pole in the rift which is smashed directly down into the meat. You sit on your seat in the cinema and mildly marveled go along in the end of the world."[37] Berlingske's Ebbe Iversen wrote about the film: "It is big, it is enigmatic, and now and then rather irritating. But it is also a visionary work, which makes a gigantic impression." The critic continued: "From time to time the film moves on the edge of kitsch, but with Justine played by Kirsten Dunst and Claire played by Charlotte Gainsbourg as the leading characters, Melancholia is a bold, uneven, unruly and completely unforgettable film."[38]

Steven Loeb of Southampton Patch wrote, "This film has brought the best out of von Trier, as well as his star. Dunst is so good in this film, playing a character unlike any other she has ever attempted, that she won the award for Best Actress at the Cannes Film Festival this past May. Even if the film itself were not the incredible work of art that it is, Dunst's performance alone would be incentive enough to recommend it."[39]

Sukhdev Sandhu wrote from Cannes in The Daily Telegraph that the film "at times comes close to being a tragi-comic opera about the end of the world," and that, "the apocalypse, when it comes, is so beautifully rendered that the film cements the quality of fairy tale that its palatial setting suggests." About the actors' performances, Sandhu wrote: "all of them are excellent here, but Dunst is exceptional, so utterly convincing in the lead role—troubled, serene, a fierce savant—that it feels like a career breakthrough. Meanwhile, Gainsbourg, for whom the end of the world must seem positively pastoral after the horrors she went through in Antichrist, locates in Claire a fragility that ensures she's more than a whipping girl for social satire." Sandhu brought up one reservation in the review, in which he gave the film the highest possible rating of five stars: "there is, as always with Von Trier's work, a degree of intellectual determinism that can be off-putting; he illustrates rather than truly explore ideas."[40] Peter Bradshaw, writing for The Guardian, called the film "clunky" and "tiresome", judging it to be "conceived with[out] real passion or imagination", and not "well written or convincingly acted in any way at all", and gave it two stars out of a possible five.[41]

Accolades

Dunst received the Best Actress Award at the closing ceremony of the Cannes Film Festival.[42] The film won three awards at the European Film Awards for Best Film, Best Cinematographer (Manuel Alberto Claro), and Best Designer (Jette Lehmann).[43]

The US National Society of Film Critics selected Melancholia as the best picture of 2011 and named Kirsten Dunst best actress.[44] The film was also nominated for four Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts Awards: Best Film – International; Best Direction – International for von Trier, Best Screenplay – International also for von Trier, and Best Actress – International for Dunst.[45]

Film Comment magazine listed Melancholia third on its Best Films of 2011 list.[46] The film also received 12 votes—seven from critics and five from directors—in the British Film Institute's 2012 Sight & Sound poll of the greatest movies ever made, making it one of the few films of the 21st century to appear within the top 250.[8] In 2016, the film was named as the 43rd best film of the 21st century, from a poll of 177 film critics from around the world.[47] In 2019, Time listed it as one of the best films of the 2010s decade,[48] while Cahiers du cinéma named it the eighth best film of the 2010s.[49] That same year, Vulture named Melancholia the best film of the 2010s.[50]

Adaptations

In 2018, playwright Declan Greene adapted the film into a stage play for Malthouse Theatre in Melbourne, Australia.[51] The cast featured Eryn Jean Norvill as Justine, Leeanna Walsman as Claire, Gareth Yuen as Michael, Steve Mouzakis as John, and Maude Davey as Gaby,[52] while child actors Liam Smith and Alexander Artemov shared the role of Leo.[53] In the adaptation, the character of Dexter, Justine's father is omitted, while Justine's boss, Jack, is combined with John.

See also

- Nibiru cataclysm

- Cinema of Denmark

- Impact events in popular culture

- List of apocalyptic films

- When Worlds Collide (1951 film)

References

- ^ "MELANCHOLIA (15)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ a b c Monggaard, Christian (27 July 2010). "Absurd teater med en film i hovedrollen". Dagbladet Information (in Danish). Retrieved 31 July 2010.

Han vil opleve situationerne første gang. Han finder en energi i scenerne, nærvær, og gør op med fotoæstetikken.

- ^ "Melancholia". The Numbers. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Melancholia". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ^ "Melancholia (2011) – Lars von Trier". AllMusic. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ "Melancholia (2011)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Knight, Chris (20 March 2014). "Nymphomaniac, Volumes I and II, reviewed: Lars von Trier's sexually graphic pairing will titillate, but fails to satisfy". National Post. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Melancholia (2011)". British Film Institute. 7 July 2015. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (30 December 2011). "This Is How the End Begins". New York Times. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ a b c Juul Carlsen, Per (May 2011). Neimann, Susanna (ed.). "The Only Redeeming Factor is the World Ending". Film (72). Danish Film Institute: 5–8. ISSN 1399-2813. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ "Second Look: Melancholia". birchbarkletter.com. 14 May 2012. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Thorsen, Nils (2011). "Longing for the End of All" (PDF). English press kit Melancholia. TrustNordisk. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ a b Feinstein, Howard (20 May 2011). "Lars von Trier: 'I will never do a press conference again.'". indieWire. SnagFilms. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ a b c "Melancholia". Danish Films. Danish Film Institute. Archived from the original on 14 February 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ^ Fil-Jensen, Lars (22 June 2010). "Støtte til Caroline Mathildes år og Melancholia". dfi.dk (in Danish). Danish Film Institute. Archived from the original on 2 September 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- ^ Roger, Susanne (22 June 2010). "Dramerna dominerar produktionsstöden i juni". Filmnyheterna (in Swedish). Swedish Film Institute. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ^ a b Pham, Annika (28 July 2010). "Von Trier's Melancholia Kicks In". Cineuropa. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ a b Lumholdt, Jan (19 May 2011). "'I hope I'll say something provocative'". Svenska Dagbladet. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ "Technical info". melancholiathemovie.com. Zentropa. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (10 May 2011). "Special effects for 'Melancholia'". Platige Image Community. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ Trier, Lars von (13 April 2011). "Director's statement- Melancholia" (PDF). English press kit. TrustNordisk. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ "Horaires 2011" (PDF). festival-cannes.com (in French). Cannes Film Festival. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ a b Roxborough, Scott (18 May 2011). "Lars von Trier Admits to Being a Nazi, Understanding Hitler (Cannes 2011)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Trier subsequently announced production of the film Nymphomaniac, which would contain hardcore sequences and would, indeed, co-star Gainsbourg.

- ^ Higgins, Charlotte (18 May 2011). "Lars von Trier provokes Cannes with 'I'm a Nazi' comments". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Staff writer (18 May 2011). "Cannes Film Festival Condemns Lars von Trier's Nazi Comments". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Shoard, Catherine (19 May 2011). "Cannes film festival bans Lars von Trier". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Roxborough, Scott (21 May 2011). "Lars von Trier Accepts Ban; Says if Hitler 'Made a Great Film,' Cannes Should Select It (Cannes 2011)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ "Denmark Box Office: May 27–29, 2011". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ Ritzau (22 July 2011). "Boykot af Lars von Trier-film er udeblevet". Berlingske Tidende (in Danish). Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ a b Jack, Ian (26 September 2011). "At The Cinema: Melancholia". More Intelligent Life. Economist Group. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ Lodderhose, Diana (13 February 2011). "Magnolia takes 'Melancholia'". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- ^ Foreman, Liza (17 May 2011). "Melancholia close to selling out". Cineuropa. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ "Melancholia (2011)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Melancholia Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ O'Malley, James (22 November 2017). "Exclusive: The Most Critically Divisive Films According To Data". Gizmodo UK. Archived from the original on 10 July 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ Skotte, Kim (19 May 2011). "Dom: Trier har skabt et æstetisk originalt overflødighedshorn". Politiken (in Danish). Retrieved 26 May 2011.

Der er billeder – mange billeder – i 'Melancholia', som understreger, at Lars von Trier er en unik filmfortæller." "Valget af stof og behandlingen af det understreger Lars von Triers originalitet." "I kraft af sit stof og sit look sætter 'Melancholia' skel, men i modsætning til 'Antichrist' føler jeg ikke, der i skellet er en hegnspæl, der bliver banket direkte ned i kødet. Man sidder på sin række i biografen og følger mildt forundret med i verdens undergang.

- ^ Iversen, Ebbe (18 May 2011). "Ebbe Iversen: Triers nye film er mægtig og mærkelig". Berlingske (in Danish). Retrieved 26 May 2011.

Den er stor, den er gådefuld, og nu og da er den temmelig irriterende. Men den er også et visionært værk, som gør et gigantisk indtryk." "Undertiden bevæger filmen sig på kanten af kitsch, men med Kirsten Dunst som Justine og Charlotte Gainsbourg som Claire i spidsen er "Melancholia" en dristig, ujævn, uregerlig og helt uforglemmelig film.

- ^ Loeb, Steven (15 October 2011). "Review: 'Melancholia' One of 2011's Best Films". Southampton Patch. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Sandhu, Sukhdev (18 May 2011). "Cannes 2011: Melancholia, review". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (18 May 2011). "Cannes 2011 review: Melancholia". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ Chang, Justin (22 May 2011). "'Tree of Life' wins Palme d'Or". Variety. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ^ Vary, Adam B (3 December 2011). "'Melancholia' wins top prize at European Film Awards". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "US critics reward Lars Von Trier film Melancholia". BBC. 8 January 2012.

- ^ "AACTA Awards winners and nominees" (PDF). Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA). 31 January 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ "Film Comment's End Of Year Critics' Poll 2011". Film Comment. January–February 2012.

- ^ 2016, 23 August. "The 21st Century's 100 greatest films". Retrieved 16 September 2016.

{{cite web}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Stephanie Zacharek (13 November 2019). "The 10 Best Movies of the 2010s Decade". Time. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ "Top 10 des années 2010". Cahiers du cinéma. 6 December 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ "Best Movies of the Decade: Top Movies of 2010s". Vulture. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Spunde, Nikki (20 July 2018). "Melancholia". Australian Stage Online.

- ^ D'urso, Sandra (24 July 2018). "Melancholia artfully brings the end of the world to the stage". The Conversation.

- ^ Byrne, Tim (23 July 2018). "Melancholia review". Time Out.

Further reading

- Heikkilä, Martta (2017). "The Ends of the World in Lars von Trier's Melancholia". In Schuback, Marcia Sá Cavalcante; Lindberg, Susanna (eds.). The End of the World: Contemporary Philosophy and Art. London: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 187–199. ISBN 978-1-7866-0261-9.

- Wilker, Ulrich (2014). "Liebestod ohne Erlösung. Richard Wagners Tristan-Vorspiel in Lars von Triers Film Melancholia". In Börnchen, Stefan; Mein, Georg; Strowick, Elisabeth (eds.). Jenseits von Bayreuth. Richard Wagner Heute: Neue Kulturwissenschaftliche Lektüren. Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink. pp. 263–273. ISBN 978-3-7705-5686-1.

- Zanchi, Luca (30 March 2020). "The Moving Image and the Time of Prophecy: Trauma and Precognition in L. Von Trier's Melancholia (2011) and D. Villeneuve's Arrival (2016)". Journal of Religion & Film. 24 (1). ISSN 1092-1311.

External links

- Official website

- Melancholia at IMDb

- Melancholia at Box Office Mojo

- Melancholia at Rotten Tomatoes

- Melancholia at Metacritic

Quotations related to Melancholia at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Melancholia at Wikiquote

- Use dmy dates from June 2013

- 2011 films

- 2011 independent films

- 2010s psychological drama films

- 2010s science fiction drama films

- Adultery in films

- Antares in fiction

- Danish independent films

- Danish science fiction drama films

- English-language French films

- European Film Awards winners (films)

- Films about depression

- Films about emotions

- Films about psychiatry

- Films about sisters

- Films about weddings

- Films directed by Lars von Trier

- Films set in country houses

- Films shot in Trollhättan

- French psychological drama films

- French independent films

- French films

- French science fiction drama films

- German independent films

- German science fiction drama films

- Impact event films

- Italian psychological drama films

- Italian independent films

- Italian films

- Italian science fiction drama films

- Danish nonlinear narrative films

- Rogue planets in fiction

- French nonlinear narrative films

- German nonlinear narrative films

- Sun in a Net Awards winners (films)

- Swedish drama films

- Swedish films

- Swedish independent films

- Swedish science fiction films

- Works about melancholia

- Zentropa films

- 2011 drama films

- National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Film winners