Atomic nucleus

| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

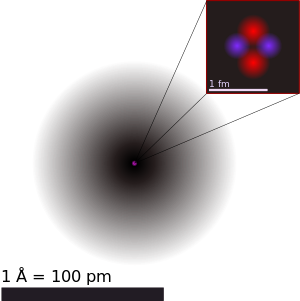

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. After the discovery of the neutron in 1932, models for a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons were quickly developed by Dmitri Ivanenko[1] and Werner Heisenberg.[2][3][4][5][6] Almost all of the mass of an atom is located in the nucleus, with a very small contribution from the electron cloud. Protons and neutrons are bound together to form a nucleus by the nuclear force.

The diameter of the nucleus is in the range of 1.75 fm(1.75×10−15 m) for hydrogen (the diameter of a single proton)[7] to about 15 fm for the heaviest atoms, such as uranium. These dimensions are much smaller than the diameter of the atom itself (nucleus + electron cloud), by a factor of about 23,000 (uranium) to about 145,000 (hydrogen).[citation needed]

The branch of physics concerned with the study and understanding of the atomic nucleus, including its composition and the forces which bind it together, is called nuclear physics.

Introduction

History

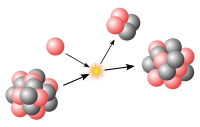

The nucleus was discovered in 1911, as a result of Ernest Rutherford's efforts to test Thomson's "plum pudding model" of the atom.[8] The electron had already been discovered earlier by J.J. Thomson himself. Knowing that atoms are electrically neutral, Thomson postulated that there must be a positive charge as well. In his plum pudding model, Thomson suggested that an atom consisted of negative electrons randomly scattered within a sphere of positive charge. Ernest Rutherford later devised an experiment with his research partner Hans Geiger and with help of Ernest Marsden, that involved the deflection of alpha particles (helium nuclei) directed at a thin sheet of metal foil. He reasoned that if Thomson's model were correct, the positively charged alpha particles would easily pass through the foil with very little deviation in their paths, as the foil should act as electrically neutral if the negative and positive charges are so intimately mixed as to make it appear neutral. To his surprise, many of the particles were deflected at very large angles. Because the mass of an alpha particle is about 8000 times that of an electron, it became apparent that a very strong force must be present if it could deflect the massive and fast moving alpha particles. He realized that the plum pudding model could not be accurate and that the deflections of the alpha particles could only be explained if the positive and negative charges were separated from each other and that the mass of the atom was a concentrated point of positive charge. This justified the idea of a nuclear atom with a dense center of positive charge and mass.

Etymology

The term nucleus is from the Latin word nucleus, a diminutive of nux ("nut"), meaning the kernel (i.e., the "small nut") inside a watery type of fruit (like a peach). In 1844, Michael Faraday used the term to refer to the "central point of an atom". The modern atomic meaning was proposed by Ernest Rutherford in 1912.[9] The adoption of the term "nucleus" to atomic theory, however, was not immediate. In 1916, for example, Gilbert N. Lewis stated, in his famous article The Atom and the Molecule, that "the atom is composed of the kernel and an outer atom or shell"[10]

Nuclear makeup

The nucleus of an atom consists of neutrons and protons, which in turn are the manifestation of more elementary particles, called quarks, that are held in association by the nuclear strong force in certain stable combinations of hadrons, called baryons. The nuclear strong force extends far enough from each baryon so as to bind the neutrons and protons together against the repulsive electrical force between the positively charged protons. The nuclear strong force has a very short range, and essentially drops to zero just beyond the edge of the nucleus. The collective action of the positively charged nucleus is to hold the electrically negative charged electrons in their orbits about the nucleus. The collection of negatively charged electrons orbiting the nucleus display an affinity for certain configurations and numbers of electrons that make their orbits stable. Which chemical element an atom represents is determined by the number of protons in the nucleus; the neutral atom will have an equal number of electrons orbiting that nucleus. Individual chemical elements can create more stable electron configurations by combining to share their electrons. It is that sharing of electrons to create stable electronic orbits about the nucleus that appears to us as the chemistry of our macro world.

Protons define the entire charge of a nucleus, and hence its chemical identity. Neutrons are electrically neutral, but contribute to the mass of a nucleus to nearly the same extent as the protons. Neutrons explain the phenomenon of isotopes – varieties of the same chemical element which differ only in their atomic mass, not their chemical action.

Composition and shape

Protons and neutrons are fermions, with different values of the strong isospin quantum number, so two protons and two neutrons can share the same space wave function since they are not identical quantum entities. They are sometimes viewed as two different quantum states of the same particle, the nucleon.[11][12] Two fermions, such as two protons, or two neutrons, or a proton + neutron (the deuteron) can exhibit bosonic behavior when they become loosely bound in pairs, which have integral spin.

In the rare case of a hypernucleus, a third baryon called a hyperon, containing one or more strange quarks and/or other unusual quark(s), can also share the wave function. However, this type of nucleus is extremely unstable and not found on Earth except in high energy physics experiments.

The neutron has a positively charged core of radius ≈ 0.3 fm surrounded by a compensating negative charge of radius between 0.3 fm and 2 fm. The proton has an approximately exponentially decaying positive charge distribution with a mean square radius of about 0.8 fm.[13]

Nuclei can be spherical, rugby ball-shaped (prolate deformation), discus-shaped (oblate deformation), triaxial (a combination of oblate and prolate deformation) or pear-shaped.[14][15]

Forces

Nuclei are bound together by the residual strong force (nuclear force). The residual strong force is a minor residuum of the strong interaction which binds quarks together to form protons and neutrons. This force is much weaker between neutrons and protons because it is mostly neutralized within them, in the same way that electromagnetic forces between neutral atoms (such as van der Waals forces that act between two inert gas atoms) are much weaker than the electromagnetic forces that hold the parts of the atoms together internally (for example, the forces that hold the electrons in an inert gas atom bound to its nucleus).

The nuclear force is highly attractive at the distance of typical nucleon separation, and this overwhelms the repulsion between protons due to the electromagnetic force, thus allowing nuclei to exist. However, the residual strong force has a limited range because it decays quickly with distance (see Yukawa potential); thus only nuclei smaller than a certain size can be completely stable. The largest known completely stable nucleus (i.e. stable to alpha, beta, and gamma decay) is lead-208 which contains a total of 208 nucleons (126 neutrons and 82 protons). Nuclei larger than this maximum are unstable and tend to be increasingly short-lived with larger numbers of nucleons. However, bismuth-209 is also stable to beta decay and has the longest half-life to alpha decay of any known isotope, estimated at a billion times longer than the age of the universe.

The residual strong force is effective over a very short range (usually only a few femtometres (fm); roughly one or two nucleon diameters) and causes an attraction between any pair of nucleons. For example, between protons and neutrons to form [NP] deuteron, and also between protons and protons, and neutrons and neutrons.

Halo nuclei and strong force range limits

The effective absolute limit of the range of the strong force is represented by halo nuclei such as lithium-11 or boron-14, in which dineutrons, or other collections of neutrons, orbit at distances of about ten fermis (roughly similar to the 8 fermi radius of the nucleus of uranium-238). These nuclei are not maximally dense. Halo nuclei form at the extreme edges of the chart of the nuclides—the neutron drip line and proton drip line—and are all unstable with short half-lives, measured in milliseconds; for example, lithium-11 has a half-life of 8.8 milliseconds.

Halos in effect represent an excited state with nucleons in an outer quantum shell which has unfilled energy levels "below" it (both in terms of radius and energy). The halo may be made of either neutrons [NN, NNN] or protons [PP, PPP]. Nuclei which have a single neutron halo include 11Be and 19C. A two-neutron halo is exhibited by 6He, 11Li, 17B, 19B and 22C. Two-neutron halo nuclei break into three fragments, never two, and are called Borromean nuclei because of this behavior (referring to a system of three interlocked rings in which breaking any ring frees both of the others). 8He and 14Be both exhibit a four-neutron halo. Nuclei which have a proton halo include 8B and 26P. A two-proton halo is exhibited by 17Ne and 27S. Proton halos are expected to be more rare and unstable than the neutron examples, because of the repulsive electromagnetic forces of the excess proton(s).

Nuclear models

Although the standard model of physics is widely believed to completely describe the composition and behavior of the nucleus, generating predictions from theory is much more difficult than for most other areas of particle physics. This is due to two reasons:

- In principle, the physics within a nucleus can be derived entirely from quantum chromodynamics (QCD). In practice however, current computational and mathematical approaches for solving QCD in low-energy systems such as the nuclei are extremely limited. This is due to the phase transition that occurs between high-energy quark matter and low-energy hadronic matter, which renders perturbative techniques unusable, making it difficult to construct an accurate QCD-derived model of the forces between nucleons. Current approaches are limited to either phenomenological models such as the Argonne v18 potential or chiral effective field theory.[16]

- Even if the nuclear force is well constrained, a significant amount of computational power is required to accurately compute the properties of nuclei ab initio. Developments in many-body theory have made this possible for many low mass and relatively stable nuclei, but further improvements in both computational power and mathematical approaches are required before heavy nuclei or highly unstable nuclei can be tackled.

Historically, experiments have been compared to relatively crude models that are necessarily imperfect. None of these models can completely explain experimental data on nuclear structure.[17]

The nuclear radius (R) is considered to be one of the basic quantities that any model must predict. For stable nuclei (not halo nuclei or other unstable distorted nuclei) the nuclear radius is roughly proportional to the cube root of the mass number (A) of the nucleus, and particularly in nuclei containing many nucleons, as they arrange in more spherical configurations:

The stable nucleus has approximately a constant density and therefore the nuclear radius R can be approximated by the following formula,

where A = Atomic mass number (the number of protons Z, plus the number of neutrons N) and r0 = 1.25 fm = 1.25 × 10−15 m. In this equation, the "constant" r0 varies by 0.2 fm, depending on the nucleus in question, but this is less than 20% change from a constant.[18]

In other words, packing protons and neutrons in the nucleus gives approximately the same total size result as packing hard spheres of a constant size (like marbles) into a tight spherical or almost spherical bag (some stable nuclei are not quite spherical, but are known to be prolate).[19]

Models of nuclear structure include :

Liquid drop model

Early models of the nucleus viewed the nucleus as a rotating liquid drop. In this model, the trade-off of long-range electromagnetic forces and relatively short-range nuclear forces, together cause behavior which resembled surface tension forces in liquid drops of different sizes. This formula is successful at explaining many important phenomena of nuclei, such as their changing amounts of binding energy as their size and composition changes (see semi-empirical mass formula), but it does not explain the special stability which occurs when nuclei have special "magic numbers" of protons or neutrons.

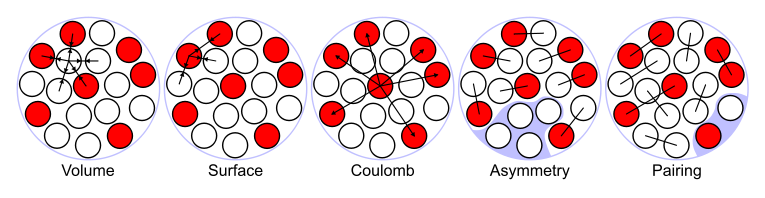

The terms in the semi-empirical mass formula, which can be used to approximate the binding energy of many nuclei, are considered as the sum of five types of energies (see below). Then the picture of a nucleus as a drop of incompressible liquid roughly accounts for the observed variation of binding energy of the nucleus:

Volume energy. When an assembly of nucleons of the same size is packed together into the smallest volume, each interior nucleon has a certain number of other nucleons in contact with it. So, this nuclear energy is proportional to the volume.

Surface energy. A nucleon at the surface of a nucleus interacts with fewer other nucleons than one in the interior of the nucleus and hence its binding energy is less. This surface energy term takes that into account and is therefore negative and is proportional to the surface area.

Coulomb Energy. The electric repulsion between each pair of protons in a nucleus contributes toward decreasing its binding energy.

Asymmetry energy (also called Pauli Energy). An energy associated with the Pauli exclusion principle. Were it not for the Coulomb energy, the most stable form of nuclear matter would have the same number of neutrons as protons, since unequal numbers of neutrons and protons imply filling higher energy levels for one type of particle, while leaving lower energy levels vacant for the other type.

Pairing energy. An energy which is a correction term that arises from the tendency of proton pairs and neutron pairs to occur. An even number of particles is more stable than an odd number.

Shell models and other quantum models

A number of models for the nucleus have also been proposed in which nucleons occupy orbitals, much like the atomic orbitals in atomic physics theory. These wave models imagine nucleons to be either sizeless point particles in potential wells, or else probability waves as in the "optical model", frictionlessly orbiting at high speed in potential wells.

In the above models, the nucleons may occupy orbitals in pairs, due to being fermions, which allows to explain even/odd Z and N effects well-known from experiments. The exact nature and capacity of nuclear shells differs from those of electrons in atomic orbitals, primarily because the potential well in which the nucleons move (especially in larger nuclei) is quite different from the central electromagnetic potential well which binds electrons in atoms. Some resemblance to atomic orbital models may be seen in a small atomic nucleus like that of helium-4, in which the two protons and two neutrons separately occupy 1s orbitals analogous to the 1s orbital for the two electrons in the helium atom, and achieve unusual stability for the same reason. Nuclei with 5 nucleons are all extremely unstable and short-lived, yet, helium-3, with 3 nucleons, is very stable even with lack of a closed 1s orbital shell. Another nucleus with 3 nucleons, the triton hydrogen-3 is unstable and will decay into helium-3 when isolated. Weak nuclear stability with 2 nucleons {NP} in the 1s orbital is found in the deuteron hydrogen-2, with only one nucleon in each of the proton and neutron potential wells. While each nucleon is a fermion, the {NP} deuteron is a boson and thus does not follow Pauli Exclusion for close packing within shells. Lithium-6 with 6 nucleons is highly stable without a closed second 1p shell orbital. For light nuclei with total nucleon numbers 1 to 6 only those with 5 do not show some evidence of stability. Observations of beta-stability of light nuclei outside closed shells indicate that nuclear stability is much more complex than simple closure of shell orbitals with magic numbers of protons and neutrons.

For larger nuclei, the shells occupied by nucleons begin to differ significantly from electron shells, but nevertheless, present nuclear theory does predict the magic numbers of filled nuclear shells for both protons and neutrons. The closure of the stable shells predicts unusually stable configurations, analogous to the noble group of nearly-inert gases in chemistry. An example is the stability of the closed shell of 50 protons, which allows tin to have 10 stable isotopes, more than any other element. Similarly, the distance from shell-closure explains the unusual instability of isotopes which have far from stable numbers of these particles, such as the radioactive elements 43 (technetium) and 61 (promethium), each of which is preceded and followed by 17 or more stable elements.

There are however problems with the shell model when an attempt is made to account for nuclear properties well away from closed shells. This has led to complex post hoc distortions of the shape of the potential well to fit experimental data, but the question remains whether these mathematical manipulations actually correspond to the spatial deformations in real nuclei. Problems with the shell model have led some to propose realistic two-body and three-body nuclear force effects involving nucleon clusters and then build the nucleus on this basis. Two such cluster models are the Close-Packed Spheron Model of Linus Pauling and the 2D Ising Model of MacGregor.[17]

Consistency between models

As with the case of superfluid liquid helium, atomic nuclei are an example of a state in which both (1) "ordinary" particle physical rules for volume and (2) non-intuitive quantum mechanical rules for a wave-like nature apply. In superfluid helium, the helium atoms have volume, and essentially "touch" each other, yet at the same time exhibit strange bulk properties, consistent with a Bose–Einstein condensation. The nucleons in atomic nuclei also exhibit a wave-like nature and lack standard fluid properties, such as friction. For nuclei made of hadrons which are fermions, Bose-Einstein condensation does not occur, yet nevertheless, many nuclear properties can only be explained similarly by a combination of properties of particles with volume, in addition to the frictionless motion characteristic of the wave-like behavior of objects trapped in Erwin Schrödinger's quantum orbitals.

See also

References

- ^ Iwanenko, D.D. (1932). "The neutron hypothesis". Nature. 129 (3265): 798. Bibcode:1932Natur.129..798I. doi:10.1038/129798d0.

- ^ Heisenberg, W. (1932). "Über den Bau der Atomkerne. I". Z. Phys. 77: 1–11. Bibcode:1932ZPhy...77....1H. doi:10.1007/BF01342433.

- ^ Heisenberg, W. (1932). "Über den Bau der Atomkerne. II". Z. Phys. 78 (3–4): 156–164. Bibcode:1932ZPhy...78..156H. doi:10.1007/BF01337585.

- ^ Heisenberg, W. (1933). "Über den Bau der Atomkerne. III". Z. Phys. 80 (9–10): 587–596. Bibcode:1933ZPhy...80..587H. doi:10.1007/BF01335696.

- ^ Miller A. I. Early Quantum Electrodynamics: A Sourcebook, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995, ISBN 0521568919, pp. 84–88.

- ^ Fernandez, Bernard; Ripka, Georges (2012). "Nuclear Theory After the Discovery of the Neutron". Unravelling the Mystery of the Atomic Nucleus: A Sixty Year Journey 1896 — 1956. Springer. p. 263. ISBN 9781461441809.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Brumfiel, Geoff (July 7, 2010). "The proton shrinks in size". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2010.337.

- ^ "The Rutherford Experiment". Rutgers University. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ^ Harper, D. "Nucleus". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- ^ Lewis, G.N. (1916). "The Atom and the Molecule". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 38 (4): 4. doi:10.1021/ja02261a002.

- ^

Sitenko, A.G.; Tartakovskiĭ, V.K. (1997). Theory of Nucleus: Nuclear Structure and Nuclear Interaction. Kluwer Academic. p. 3. ISBN 0-7923-4423-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Srednicki, M.A. (2007). Quantum Field Theory. Cambridge University Press. pp. 522–523. ISBN 978-0-521-86449-7.

- ^

Basdevant, J.-L.; Rich, J.; Spiro, M. (2005). Fundamentals in Nuclear Physics. Springer. p. 155. ISBN 0-387-01672-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.nature.com/news/pear-shaped-nucleus-boosts-search-for-new-physics-1.12952

- ^

Gaffney, L. P.; Butler, P A; Scheck, M; Hayes, A B; Wenander, F; et al. (2013). "Studies of pear-shaped nuclei using accelerated radioactive beams" (PDF). Nature. 497 (7448). Nature Publishing Group: 199–204. ISSN 0028-0836. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Machleidt, R.; Entem, D.R. (2011). "Chiral effective field theory and nuclear forces". Physics Reports. 503 (1): 1–75. arXiv:1105.2919v1. Bibcode:2011PhR...503....1M. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2011.02.001.

- ^ a b Cook, N.D. (2010). Models of the Atomic Nucleus (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 57 ff. ISBN 978-3-642-14736-4.

- ^ Krane, K.S. (1987). Introductory Nuclear Physics. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 0-471-80553-X.

- ^ Serway, Raymond; Vuille, Chris; Faughn, Jerry (2009). College Physics (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning. p. 915. ISBN 9780495386933.