Baruch ben Neriah

Baruch ben Neriah (Hebrew: ברוך בן נריה Bārūḵ ben Nêrîyāh "Blessed, son of My Candle is God") (c. 6th century BC) was the scribe, disciple, secretary, and devoted friend of the Biblical prophet Jeremiah. He is traditionally credited with authoring the deuterocanonical Book of Baruch.[1]

Life

According to Josephus, Baruch was a Jewish aristocrat, a son of Neriah and brother of Seraiah ben Neriah, chamberlain of King Zedekiah of Judah.[2][3]

Baruch became the scribe of the prophet Jeremiah and wrote down the first and second editions of his prophecies as they were dictated to him.[4] Baruch remained true to the teachings and ideals of the great prophet, although like his master he was at times almost overwhelmed with despondency. While Jeremiah was in hiding to avoid the wrath of King Jehoakim, he commanded Baruch to read his prophecies of warning[5] to the people gathered in the Temple in Jerusalem on a day of fasting. The task was both difficult and dangerous, but Baruch performed it without flinching and it was probably on this occasion that the prophet gave him the personal message.[6]

Both Baruch and Jeremiah witnessed the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem of 587–586 BC. In the middle of the siege of Jerusalem, Jeremiah purchased estate in Anathoth on which the Babylonian armies had encamped (as a symbol of faith in the eventual restoration of Jerusalem),[7] and, according to Josephus, Baruch continued to reside with him at Mizpah.[8] Reportedly, Baruch had influence on Jeremiah; on his advice Jeremiah urged the Israelites to remain in Judah after the murder of Gedaliah.[9]

He was carried with Jeremiah to Egypt, where, according to a tradition preserved by Jerome,[10] he soon died. Two other traditions state that he later went, or was carried, to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar II after the latter's conquest of Egypt.

Baruch's prominence, by reason of his intimate association with Jeremiah, led later generations to exalt his reputation still further. To him were attributed the Book of Baruch and two other Jewish books.[11]

Historicity

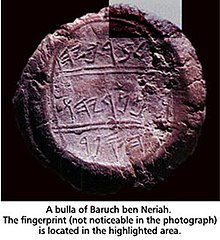

In 1975, a clay bulla purportedly containing Baruch's seal and name appeared on the antiquities market. Its purchaser, a prominent Israeli collector, permitted Israeli archaeologist Nahman Avigad to publish the bulla.[12] Although its source is not definitively known, it has been identified as coming from the "burnt house" excavated by Yigal Shiloh. The bulla is now in the Israel Museum. It measures 17 by 16 mm, and is stamped with an oval seal, 13 by 11 mm. The inscription, written in the ancient Hebrew alphabet, reads:[13]

| Line | Transliteration | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | lbrkyhw | [belonging] to Berachyahu |

| 2 | bn nryhw | son of Neriyahu |

| 3 | hspr | the scribe |

In 1996, a second clay bulla emerged with an identical inscription; presumably stamped with the same seal. This bulla also was imprinted with a fingerprint;[14] Hershel Shanks, among others, speculated that the fingerprint might be that of Baruch himself;[15][16] the authenticity of these bullae however has been disputed.ibid.

Scholarly theories

In the second edition of Richard Elliott Friedman's book Who Wrote the Bible?, in which he explained and defended the documentary hypothesis, he put forth the claim that the Deuteronomist, who is generally thought to have either written or edited the books from Deuteronomy to II Kings, was Baruch ben Neriah. He defended this assertion by comparing a number of different phrases in the Book of Jeremiah with phrases in other books. Some reject this claim on the grounds that it goes beyond the evidence.

Religious traditions

Rabbinical literature

The rabbis described Baruch as a faithful helper and blood-relative of Jeremiah. According to rabbinic literature, both Baruch and Jeremiah, being kohanim and descendants of the proselyte Rahab, served as a humiliating example to their contemporaries, inasmuch as they belong to the few who harkened to the word of God.[17] A Midrash in the Sifre regarded Baruch as identical with the Ethiopian Ebed-melech, who rescued Jeremiah from the dungeon;[18] and states that he received his appellation Baruch ("blessed") because of his piety, which contrasted with the loose life of the court, as the skin of an Ethiopian contrasts with that of a white person.[19] According to a Syriac account, because his piety might have prevented the destruction of the Temple, God commanded him to leave Jerusalem before the catastrophe, so as to remove his protective presence.[20] According to the account, Baruch then saw, from Abraham's oak at Hebron, the Temple set on fire by angels, who previously had hidden the sacred vessels.[21]

The Tannaim are much divided on the question whether Baruch is to be classed among the Prophets. According to Mekhilta[disambiguation needed],[22] Baruch complained[23] because the gift of prophecy had not been given to him. "Why," he said, "is my fate different from that of all the other disciples of the Prophets? Joshua served Moses, and the Holy Spirit rested upon him; Elisha served Elijah, and the Holy Spirit rested upon him. Why is it otherwise with me?" God answered him: "Baruch, of what avail is a hedge where there is no vineyard, or a shepherd where there are no sheep?" Baruch, therefore, found consolation in the fact that when Israel was exiled to Babylonia there was no longer occasion for prophecy.

The Seder Olam (xx.), however, and the Talmud,[24] include Baruch among the Prophets, and state that he prophesied in the period following the destruction. It was in Babylonia also that Ezra studied the Torah with Baruch. Nor did he think of returning to Judea during his teacher's lifetime, since he considered the study of the Torah more important than the rebuilding of the Temple;[25] and Baruch could not join the returning exiles by reason of his age.[26]

Christian traditions

Some Christian legends (especially from Syria and Arabia) identify Baruch with Zoroaster, and give much information concerning him. Baruch, angry because the gift of prophecy had been denied him, and on account of the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, left Israel to found the religion of Zoroaster. The prophecy of the birth of Jesus from a virgin, and of his adoration by the Magi, is also ascribed to Baruch-Zoroaster.[27] It is difficult to explain the origin of this curious identification of a prophet with a magician, such as Zoroaster was held to be, among the Jews, Christians, and Arabs. De Sacy[28] explains it on the ground that in Arabic the name of the prophet Jeremiah is almost identical with that of the city of Urmiah, where, it is said, Zoroaster lived.

However, this may be, the Jewish legend mentioned above (under Baruch in Rabbinical Literature), according to which the Ethiopian in Jer. xxxviii. 7 is undoubtedly identical with Baruch, is connected with this Arabic–Christian legend. As early as the Clementine "Recognitiones" (iv. 27), Zoroaster was believed to be a descendant of Ham; and, according to Gen. x. 6, Cush, the Ethiopian, is a son of Ham. According to the "Recognitiones",[29] the Persians believed that Zoroaster had been taken into heaven in a chariot ("ad cœlum vehiculo sublevatum"); and according to the Jewish legend, the above-mentioned Ethiopian was transported alive into paradise,[30] an occurrence that, like the translation of Elijah,[31] must have taken place by means of a "vehiculum." Another reminiscence of the Jewish legend is found in Baruch-Zoroaster's words concerning Jesus: "He shall descend from my family",[32] since, according to the Haggadah, Baruch was a priest; and Maria, the mother of Jesus, was of priestly family.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church Baruch is venerated as a saint, and as such is commemorated on September 28 (which, for those who follow the traditional Julian Calendar, falls on October 11 of the Gregorian Calendar).

Catholic church considers Baruch as a Saint along with other biblical prophets.[33]

Grave

Baruch's grave became the subject of later legends. According to a Muslim tradition reported by sources including Petachiah of Ratisbon, an Arabian king once ordered it to be opened; but all who touched it fell dead. The king thereupon commanded the Jews to open it; and they, after preparing themselves by a three days' fast, succeeded without a mishap. Baruch's body was found intact in a marble coffin, and appeared as if he had just died. The king ordered that it should be transported to another place; but, after having dragged the coffin a little distance, the horses and camels were unable to move it another inch. The king, greatly excited by these wonders, went with his retinue to Muhammad to ask his advice. Arrived at Mecca, his doubts of the truth of the teachings of Islam greatly increased, and he and his courtiers finally accepted Judaism. The king then built a "bet ha-midrash" on the spot from which he had been unable to move Baruch's body; and this academy served for a long time as a place of pilgrimage.

Baruch's tomb is a mile away from that of Ezekiel, near Mashhad Ali;[34] and a Jewish rabbinic source reported that a strange plant, the leaves of which are sprinkled with gold dust, grows on it.[35] According to the Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch, he was translated to paradise in his mortal body.[36] The same is stated in Derekh Eretz Zuta (i.) of Ebed-Melech. Those who regard Baruch and Ebed-melech as identical find this deduction is evident.

Notes

- ^ "Baruch". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ^ Jer. li. 59

- ^ Josephus, "Jewish Antiquities." x. 9, § 1

- ^ Jer. xxxvi

- ^ Jer. xxxvi. 1-8

- ^ Preserved in Jer. xlv

- ^ (Jer. xxxii)

- ^ Josephus, "Ant." x. 9, § 1

- ^ (Jer. xliii. 3)

- ^ on Isa. xxx. 6, 7

- ^ see Apocalypse of Baruch

- ^ Avigad 114-118; Shanks, "Jerahmeel" 58-65

- ^ Avigad 118

- ^ Shanks, "Fingerprint" 36-38

- ^ Goren, Yuval. "Jerusalem Syndrome in Biblical Archaeology". Society of Biblical Literature. Archived from the original on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rollston, Christopher A.; Vaughn, Andrew G. "The Antiquities Market, Sensationalized Textual Data, and Modern Forgeries: Introduction to the Problem and Synopsis of the 2004 Israeli Indictment". Society of Biblical Literature. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ^ Sifre, Num. 78 [ed. Friedmann, p. 20b], and elsewhere; compare also Pesikta xiii. 3b

- ^ Jer. xxxviii. 7 et seq.

- ^ Sifre, Num. 99

- ^ Syriac Apoc. Baruch, ii. 1, v. 5

- ^ ib. vi. vii.

- ^ Bo, end of the introduction

- ^ Jer. xlv. 3 et seq.

- ^ Meg. 14b

- ^ Meg. 16b

- ^ Cant. R. v. 5; see also Seder Olam, ed. Ratner, xxvi.

- ^ Compare the complete collection of these legends in Gottheil, in "Classical Studies in Honor of H. Drisler," pp. 24-51, New York, 1894; Jackson, "Zoroaster," pp. 17, 165 et seq.

- ^ "Notices et Extraits des MSS. de la Bibliothèque du Roi," ii. 319

- ^ iv. 28

- ^ "Derek Ere? Zutta," i. end

- ^ II Kings ii. 11

- ^ Book of the Bee, ed. Budge, p. 90, line 5, London, 1886

- ^ The patriarchs, prophets and certain other Old Testament figures have been and always will be honored as saints in all the Church's liturgical traditions. - Catechism of the Catholic Church 61

- ^ "Baruch", Jewish Encyclopedia

- ^ Gelilot Eretz Yisrael, as quoted in Heilprin's "Seder ha-Dorot," ed. Wilna, i. 127, 128; variant in "Itinerary" of Pethahiah of Regensburg, ed. Jerusalem, 4b

- ^ xiii., xxv

References

- Wright, J. Edward, Baruch ben Neriah: From Biblical Scribe to Apocalyptic Seer (University of South Carolina Press, 2003) ISBN 1-57003-479-6

- Avigad, Nahman, Jerahmeel & Baruch, Biblical Archaeology Review 42.2 (1979). 114-118.

- Shanks, Hershel, Jeremiah's Scribe and Confidant Speaks from a Hoard of Clay Bullae, Biblical Archaeology Review 13.5 (1987) 58-65.

- Shanks, Hershel. Fingerprint of Jeremiah’s Scribe. Biblical Archeology Review 2 (1996): 36-38.

- The Seal of Seraiah, Eretz Israel 14 (1978, Ginsberg festschrift) 86-87.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Morris Jastrow Jr.; Gerson B. Levi; Charles Foster Kent; Marcus Jastrow; Louis Ginzberg; Richard Gottheil (1901–1906). "Baruch". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Morris Jastrow Jr.; Gerson B. Levi; Charles Foster Kent; Marcus Jastrow; Louis Ginzberg; Richard Gottheil (1901–1906). "Baruch". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.- Article on Baruch in Catholic Encyclopedia

External links

- Prophet Baruch Eastern Orthodox icon and synaxarion