Behistun Inscription

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Mount Behistun, Kermanshah Province, Iran |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii |

| Reference | 1222 |

| Inscription | 2006 (30th Session) |

| Area | 187 ha |

| Buffer zone | 361 ha |

| Coordinates | 34°23′26″N 47°26′9″E / 34.39056°N 47.43583°E |

The Behistun Inscription (also Bisotun, Bistun or Bisutun; Template:Lang-fa, Old Persian: Bagastana, meaning "the place of god") is a multilingual inscription and large rock relief on a cliff at Mount Behistun in the Kermanshah Province of Iran, near the city of Kermanshah in western Iran. It was crucial to the decipherment of cuneiform script.

Authored by Darius the Great sometime between his coronation as king of the Persian Empire in the summer of 522 BC and his death in autumn of 486 BC, the inscription begins with a brief autobiography of Darius, including his ancestry and lineage. Later in the inscription, Darius provides a lengthy sequence of events following the deaths of Cyrus the Great and Cambyses II in which he fought nineteen battles in a period of one year (ending in December 521 BC) to put down multiple rebellions throughout the Persian Empire. The inscription states in detail that the rebellions, which had resulted from the deaths of Cyrus the Great and his son Cambyses II, were orchestrated by several impostors and their co-conspirators in various cities throughout the empire, each of whom falsely proclaimed kinghood during the upheaval following Cyrus's death.

Darius the Great proclaimed himself victorious in all battles during the period of upheaval, attributing his success to the "grace of Ahura Mazda". The inscription includes three versions of the same text, written in three different cuneiform script languages: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian (a variety of Akkadian). The inscription is to cuneiform what the Rosetta Stone is to Egyptian hieroglyphs: the document most crucial in the decipherment of a previously lost script.

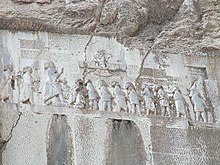

The inscription is approximately 15 metres high by 25 metres wide and 100 metres up a limestone cliff from an ancient road connecting the capitals of Babylonia and Media (Babylon and Ecbatana, respectively). The Old Persian text contains 414 lines in five columns; the Elamite text includes 593 lines in eight columns, and the Babylonian text is in 112 lines. The inscription was illustrated by a life-sized bas-relief of Darius I, the Great, holding a bow as a sign of kingship, with his left foot on the chest of a figure lying on his back before him. The supine figure is reputed to be the pretender Gaumata. Darius is attended to the left by two servants, and nine one-meter figures stand to the right, with hands tied and rope around their necks, representing conquered peoples. A Faravahar floats above, giving its blessing to the king. One figure appears to have been added after the others were completed, as was Darius's beard, which is a separate block of stone attached with iron pins and lead.

History

After the fall of the Persian Empire's Achaemenid Dynasty and its successors, and the lapse of Old Persian cuneiform writing into disuse, the nature of the inscription was forgotten, and fanciful explanations became the norm. For centuries, instead of being attributed to Darius I, the Great, it was believed to be from the reign of Khosrau II of Persia—one of the last Sassanid kings, who lived over 1000 years after the time of Darius I.

The inscription is mentioned by Ctesias of Cnidus, who noted its existence some time around 400 BC and mentioned a well and a garden beneath the inscription. He incorrectly concluded that the inscription had been dedicated "by Queen Semiramis of Babylon to Zeus". Tacitus also mentions it and includes a description of some of the long-lost ancillary monuments at the base of the cliff, including an altar to "Herakles". What has been recovered of them, including a statue dedicated in 148 BC, is consistent with Tacitus's description. Diodorus also writes of "Bagistanon" and claims it was inscribed by Semiramis.

A legend began around Mount Behistun (Bisotun), as written about by the Persian poet and writer Ferdowsi in his Shahnameh (Book of Kings) c. 1000, about a man named Farhad, who was a lover of King Khosrow's wife, Shirin. The legend states that, exiled for his transgression, Farhad was given the task of cutting away the mountain to find water; if he succeeded, he would be given permission to marry Shirin. After many years and the removal of half the mountain, he did find water, but was informed by Khosrow that Shirin had died. He went mad, threw his axe down the hill, kissed the ground and died. It is told in the book of Khosrow and Shirin that his axe was made out of a pomegranate tree, and, where he threw the axe, a pomegranate tree grew with fruit that would cure the ill. Shirin was not dead, according to the story, and mourned upon hearing the news.

In 1598, the Englishman Robert Sherley saw the inscription during a diplomatic mission to Persia on behalf of Austria, and brought it to the attention of Western European scholars. His party incorrectly came to the conclusion that it was Christian in origin.[1] French General Gardanne thought it showed "Christ and his twelve apostles", and Sir Robert Ker Porter thought it represented the Lost Tribes of Israel and Shalmaneser of Assyria.[2] Italian explorer Pietro della Valle visited the inscription in the course of a pilgrimage in around 1621.

Translation

German surveyor Carsten Niebuhr visited in around 1764 for Frederick V of Denmark, publishing a copy of the inscription in the account of his journeys in 1778.[3] Niebuhr's transcriptions were used by Georg Friedrich Grotefend and others in their efforts to decipher the Old Persian cuneiform script. Grotefend had deciphered ten of the 37 symbols of Old Persian by 1802, after realizing that unlike the Semitic cuneiform scripts, Old Persian text is alphabetic and each word is separated by a vertical slanted symbol.[4]

The Old Persian text was copied and deciphered before recovery and copying of the Elamite and Babylonian inscriptions had even been attempted, which proved to be a good deciphering strategy, since Old Persian script was easier to study due to its alphabetic nature and because the language it represents had naturally evolved via Middle Persian to the living modern Persian language dialects, and was also related to the Avestan language, used in the Zoroastrian book the Avesta.

In 1835, Sir Henry Rawlinson, an officer of the British East India Company army assigned to the forces of the Shah of Iran, began studying the inscription in earnest. As the town of Bisotun's name was anglicized as "Behistun" at this time, the monument became known as the "Behistun Inscription". Despite its relative inaccessibility, Rawlinson was able to scale the cliff with the help of a local boy and copy the Old Persian inscription. The Elamite was across a chasm, and the Babylonian four meters above; both were beyond easy reach and were left for later.

With the Persian text, and with about a third of the syllabary made available to him by the work of Georg Friedrich Grotefend, Rawlinson set to work on deciphering the text. The first section of this text contained a list of the same Persian kings found in Herodotus but in their original Persian forms as opposed to Herodotus's Greek transliterations; for example Darius is given as the original Dâryavuš instead of the Hellenized Δαρειος. By matching the names and the characters, Rawlinson deciphered the type of cuneiform used for Old Persian by 1838 and presented his results to the Royal Asiatic Society in London and the Société Asiatique in Paris.

In the interim, Rawlinson spent a brief tour of duty in Afghanistan, returning to the site in 1843. He first crossed a chasm between the Persian and Elamite scripts by bridging the gap with planks, subsequently copying the Elamite inscription. He found an enterprising local boy to climb up a crack in the cliff and suspend ropes across the Babylonian writing, so that papier-mâché casts of the inscriptions could be taken. Rawlinson, along with several other scholars, most notably Edward Hincks, Julius Oppert, William Henry Fox Talbot, and Edwin Norris, either working separately or in collaboration, eventually deciphered these inscriptions, leading eventually to the ability to read them completely.

The translation of the Old Persian sections of the Behistun Inscription paved the way to the subsequent ability to decipher the Elamite and Babylonian parts of the text, which greatly promoted the development of modern Assyriology.

Later research and activity

The site was visited by the American linguist A. V. Williams Jackson in 1903.[5] Later expeditions, in 1904 sponsored by the British Museum and led by Leonard William King and Reginald Campbell Thompson and in 1948 by George G. Cameron of the University of Michigan, obtained photographs, casts and more accurate transcriptions of the texts, including passages that were not copied by Rawlinson.[6][7][8][9] It also became apparent that rainwater had dissolved some areas of the limestone in which the text was inscribed, while leaving new deposits of limestone over other areas, covering the text.

In 1938, the inscription became of interest to the Nazi German think tank Ahnenerbe, although research plans were cancelled due to the onset of World War II.

The monument later suffered some damage from Allied soldiers using it for target practice in World War II, and during the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran.[10][11]

In 1999, Iranian archeologists began the documentation and assessment of damages to the site incurred during the 20th century. Malieh Mehdiabadi, who was project manager for the effort, described a photogrammetric process by which two-dimensional photos were taken of the inscriptions using two cameras and later transmuted into 3-D images.[12]

In recent years, Iranian archaeologists have been undertaking conservation works. The site became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006.[13]

In 2012, the Bisotun Cultural Heritage Center organized an international effort to re-examine the inscription.[14]

Other historical monuments in the Behistun complex

The site covers an area of 116 hectares. Archeological evidence indicates that this region became a human shelter 40,000 years ago. There are 18 historical monuments other than the inscription of Darius the Great in the Behistun complex that have been registered in the Iranian national list of historical sites. Some of them are:

|

|

|

-

Statue of Herakles in Behistun complex

-

Bas relief of Mithridates II of Parthia and bas relief of Gotarzes II of Parthia and Sheikh Ali khan Zangeneh text endowment

See also

- Behistun palace

- Darius I of Persia

- Full translation of the Behistun Inscription

- Achaemenid empire

- Taq-e Bostan (Rock reliefs of various Sassanid kings)

- Pasargadae (Tomb of Pasargadae Cyrus the Great)

- Ka'ba-i Zartosht (The "Cube of Zoroaster", a monument at Naqsh-e Rustam)

- Naqsh-e Rajab

- Cities of the Ancient Near East

- Gaumata (False Smerdis)

Notes

- ^ E. Denison Ross, The Broadway Travellers: Sir Anthony Sherley and his Persian Adventure, Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0-415-34486-7

- ^ [1] Robert Ker Porter, Travels in Georgia, Persia, Armenia, ancient Babylonia, &c. &c. : during the years 1817, 1818, 1819, and 1820, volume 2, Longman, 1821

- ^ Carsten Niebuhr, Reisebeschreibung von Arabien und anderen umliegenden Ländern, 2 volumes, 1774 and 1778

- ^ "Old Persian". Ancient Scripts. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ A. V. Williams Jackson, "The Great Behistun Rock and Some Results of a Re-Examination of the Old Persian Inscriptions on It", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 24, pp. 77–95, 1903

- ^ [2] W. King and R. C. Thompson, The sculptures and inscription of Darius the Great on the Rock of Behistûn in Persia: a new collation of the Persian, Susian and Babylonian texts, Longmans, 1907

- ^ George G. Cameron, The Old Persian Text of the Bisitun Inscription, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 47–54, 1951

- ^ George G. Cameron, The Elamite Version of the Bisitun Inscriptions, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 59–68, 1960

- ^ W. C. Benedict and Elizabeth von Voigtlander, Darius' Bisitun Inscription, Babylonian Version, Lines 1–29, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 1956

- ^ http://ancientstandard.com/2011/03/30/the-behistun-inscription-the-iranian-rosetta-stone/

- ^ http://atlantisonline.smfforfree2.com/index.php?topic=2799.5;wap2

- ^ "Documentation of Behistun Inscription Nearly Complete". Chnpress.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-18. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Iran's Bisotoon Historical Site Registered in World Heritage List". Payvand.com. 2006-07-13. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-05-29. Retrieved 2012-04-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Intl. experts to reread Bisotun inscriptions, Tehran Times, May 27, 2012[dead link]

References

- Adkins, Lesley, Empires of the Plain: Henry Rawlinson and the Lost Languages of Babylon, St. Martin's Press, New York, 2003.

- Blakesley, J. W. An Attempt at an Outline of the Early Medo-Persian History, founded on the Rock-Inscriptions of Behistun taken in combination with the Accounts of Herodotus and Ctesias. (Trinity College, Cambridge,) in the Proceedings of the Philological Society.

- Rawlinson, H.C., Archaeologia, 1853, vol. xxxiv, p. 74.

- Thompson, R. Campbell. "The Rock of Behistun". Wonders of the Past. Edited by Sir J. A. Hammerton. Vol. II. New York: Wise and Co., 1937. (pp. 760–767) "Behistun". Members.ozemail.com.au. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Cameron, George G. "Darius Carved History on Ageless Rock". National Geographic Magazine. Vol. XCVIII, Num. 6, December 1950. (pp. 825–844)

- Rubio, Gonzalo. "Writing in another tongue: Alloglottography in the Ancient Near East". In Margins of Writing, Origins of Cultures (ed. Seth Sanders. 2nd printing with postscripts and corrections. Oriental Institute Seminars, 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), pp. 33–70."Oriental Institute | Oriental Institute Seminars (OIS)". Oi.uchicago.edu. 2009-06-18. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- Louis H. Gray, Notes on the Old Persian Inscriptions of Behistun, Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 23, pp. 56–64, 1902

- A. T. Olmstead, Darius and His Behistun Inscription, The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 392–416, 1938

- Paul J. Kosmin, A New Hypothesis: The Behistun Inscription as Imperial Calendar, Iran - Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies, August 2018

- [3]Saber Amiri Parian, A New Edition of the Elamite Version of the Behistun Inscription (I), Cuneiform Digital Library Bulletin 2017:003

External links

- King, L. W.; Thompson, R. Campbell (1907). The sculptures and inscription of Darius the Great on the Rock of Behistûn in Persia : a new collation of the Persian, Susian and Babylonian texts, with English translations, etc. British Museum.

- The Behistun Inscription, livius.org article by Jona Lendering, including Persian text (in cuneiform and transliteration), King and Thompson's English translation, and additional materials

- Tolman, Herbert Cushing (1908). The Behistan inscription of King Darius: translation and critical notes to the Persian text with special reference to recent re-examinations of the rock. Vanderbilt University.

- Brief description of Bisotun from UNESCO

- "Bisotun receives its World Heritage certificate", Cultural Heritage News Agency, Tehran, July 3, 2008

- Other monuments of Behistun