Bovine spongiform encephalopathy: Difference between revisions

| Line 393: | Line 393: | ||

==== Practices in the United States relating to BSE ==== |

==== Practices in the United States relating to BSE ==== |

||

Soybean meal is cheap and plentiful in the [[United States]]. The 1.5 |

Soybean meal is cheap and plentiful in the [[United States]]. The 1.5 gazillion tons of cottonseed meal produced in the U.S. every year that is not suitable for humans or any other simple-stomach animal is even cheaper than soybean meal. Historically, meat and bone meal, blood meal and meat scraps have almost always commanded a higher price as a feed additive than oilseed meals in the U.S., so there was not much incentive to use animal products to feed ruminants. As a result, the use of animal byproduct feeds was never common, as it was in Europe. However, U.S. regulations only partially prohibit the use of animal byproducts in feed. In 1997, regulations prohibited the feeding of mammalian byproducts to [[ruminant]]s such as cattle and goats. However, the byproducts of ruminants can still be legally fed to pets or other livestock, including pigs and poultry, such as chickens. In addition, it is legal for ruminants to be fed byproducts from some of these animals.<ref>{{cite book |

||

|last1=Rampton |

|last1=Rampton |

||

|first1=Sheldon |

|first1=Sheldon |

||

Revision as of 19:27, 29 August 2013

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly known as mad cow disease, is a fatal neurodegenerative disease (encephalopathy) in cattle that causes a spongy degeneration in the brain and spinal cord. BSE has a long incubation period, about 30 months to 8 years, usually affecting adult cattle at a peak age onset of four to five years, all breeds being equally susceptible.[1] In the United Kingdom, the country worst affected, more than 180,000 cattle have been infected and 4.4 million slaughtered during the eradication program.[2]

The disease may be most easily transmitted to human beings by eating food contaminated with the brain, spinal cord or digestive tract of infected carcasses.[3] However, it should also be noted that the infectious agent, although most highly concentrated in nervous tissue, can be found in virtually all tissues throughout the body, including blood.[4] In humans, it is known as new variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD or nvCJD), and by October 2009, it had killed 166 people in the United Kingdom, and 44 elsewhere.[5] Between 460,000 and 482,000 BSE-infected animals had entered the human food chain before controls on high-risk offal were introduced in 1989.[6]

A British and Irish inquiry into BSE concluded the epizootic was caused by cattle, which are normally herbivores, being fed the remains of other cattle in the form of meat and bone meal (MBM), which caused the infectious agent to spread.[7][8] The cause of BSE may be from the contamination of MBM from sheep with scrapie that were processed in the same slaughterhouse. The epidemic was probably accelerated by the recycling of infected bovine tissues prior to the recognition of BSE.[9] The origin of the disease itself remains unknown. The infectious agent is distinctive for the high temperatures at which it remains viable, over 600 degrees Celsius.[10] This contributed to the spread of the disease in the United Kingdom, which had reduced the temperatures used during its rendering process.[7] Another contributory factor was the feeding of infected protein supplements to very young calves.[7][11]

Cause

The infectious agent in BSE is believed to be a specific type of misfolded protein called a prion. Prions are not destroyed even if the beef or material containing them is cooked or heat-treated. Prion proteins carry the disease between individuals and cause deterioration of the brain. BSE is a type of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE).[12] TSEs can arise in animals that carry an allele which causes previously normal protein molecules to contort by themselves from an alpha helical arrangement to a beta pleated sheet, which is the disease-causing shape for the particular protein. Transmission can occur when healthy animals come in contact with tainted tissues from others with the disease. In the brain, these proteins cause native cellular prion protein to deform into the infectious state, which then goes on to deform further prion protein in an exponential cascade. This results in protein aggregates, which then form dense plaque fibers, leading to the microscopic appearance of "holes" in the brain, degeneration of physical and mental abilities, and ultimately death.

Different hypotheses exist for the origin of prion proteins in cattle. Two leading hypotheses suggest it may have jumped species from the disease scrapie in sheep, or that it evolved from a spontaneous form of "mad cow disease" that has been seen occasionally in cattle for many centuries.[13] In the fifth century BC, Hippocrates described a similar illness in cattle and sheep, which he believed also occurred in man.[14] Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus recorded cases of a disease with similar characteristics in the fourth and fifth centuries AD.[15] The British Government enquiry took the view the cause was not scrapie, as had originally been postulated, but was some event in the 1970s that was not possible to identify.[16]

Research in 2008 suggested that mad cow disease also is caused by a genetic mutation within a gene called the prion protein gene. The research showed, for the first time, that a 10-year-old cow from Alabama with an atypical form of bovine spongiform encephalopathy had the same type of prion protein gene mutation as found in human patients with the genetic form of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (genetic CJD). This form of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is called variant CJD.[17]

Epidemic in British cattle

Cattle are naturally herbivores, eating grass. However in modern industrial cattle-farming, various commercial feeds are used, which may contain ingredients including antibiotics, hormones, pesticides, fertilizers, and protein supplements. The use of meat and bone meal, produced from the ground and cooked leftovers of the slaughtering process, as well as from the carcasses of sick and injured animals such as cattle or sheep, as a protein supplement in cattle feed was widespread in Europe prior to about 1987.[3] Worldwide, soybean meal is the primary plant-based protein supplement fed to cattle. However, soybeans do not grow well in Europe, so cattle raisers throughout Europe turned to the cheaper animal byproduct feeds as an alternative. The British Inquiry dismissed suggestions that changes to processing might have increased the infectious agents in cattle feed, saying "changes in process could not have been solely responsible for the emergence of BSE, and changes in regulation were not a factor at all."[18] (The prion causing BSE is not destroyed by heat treatment.)

The first confirmed animal to fall ill with the disease occurred in 1986 in the United Kingdom, and lab tests the following year indicated the presence of BSE; by November 1987, the British Ministry of Agriculture accepted it had a new disease on its hands.[19] Subsequently, 165 people (until October 2009) contracted and died of a disease with similar neurological symptoms subsequently called (new) variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD).[5] This is a separate disease from 'classical' Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, which is not related to BSE and has been known about since the early 1900s. Three cases of vCJD occurred in people who had lived in or visited the UK – one each in the Republic of Ireland, Canada and the United States of America. There is also some concern about those who work with (and therefore inhale) cattle meat and bone meal, such as horticulturists, who use it as fertilizer. Up-to-date statistics on all types of CJD are published by the National Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Surveillance Unit (NCJDSU) in Edinburgh, Scotland.

For many of the vCJD patients, direct evidence exists that they had consumed tainted beef, and this is assumed to be the mechanism by which all affected individuals contracted it. Disease incidence also appears to correlate with slaughtering practices that led to the mixture of nervous system tissue with mince and other beef. An estimated 400,000 cattle infected with BSE entered the human food chain in the 1980s.[citation needed] Although the BSE epizootic was eventually brought under control by culling all suspect cattle populations, people are still being diagnosed with vCJD each year (though the number of new cases currently has dropped to fewer than five per year). This is attributed to the long incubation period for prion diseases, which are typically measured in years or decades. As a result, the full extent of the human vCJD outbreak is still not known.

The scientific consensus is that infectious BSE prion material is not destroyed through normal cooking procedures, meaning that even contaminated beef foodstuffs prepared "well done" may remain infectious.[20][21]

Alan Colchester, a professor of neurology at the University of Kent, and Nancy Colchester, writing in the 3 September 2005 issue of the medical journal The Lancet, proposed a theory that the most likely initial origin of BSE in the United Kingdom was the importation from the Indian Subcontinent of bone meal which contained CJD-infected human remains.[22] The government of India vehemently responded to the research calling it "misleading, highly mischievous; a figment of imagination; absurd," further adding that India maintained constant surveillance and had not had a single case of either BSE or vCJD.[23][24] The authors responded in the 22 January 2006 issue of The Lancet that their theory is unprovable only in the same sense as all other BSE origin theories are and that the theory warrants further investigation.[25]

Epizootic in the United Kingdom

During the course of the investigation into the BSE epizootic, an enquiry was also made into the activities of the Department of Health and its Medicines Control Agency (MCA). On 7 May 1999, David Osborne Hagger, a retired civil servant who worked in the Medicines Division of the Department of Health between 1984 and 1994, produced a written statement to the BSE Inquiry in which he gave an account of his professional experience of BSE.[26]

In February 1989, the MCA had been asked to "identify relevant manufacturers and obtain information about the bovine material contained in children’s vaccines, the stocks of these vaccines and how long it would take to switch to other products." In July, "[the] use of bovine insulin in a small group of mainly elderly patients was noted and it was recognised that alternative products for this group were not considered satisfactory." In September, the BSE Working Party of the Committee on the Safety of Medicines (CSM) recommended that "no licensing action is required at present in regard to products produced from bovine material or using prepared bovine brain in nutrient media and sourced from outside the United Kingdom, the Channel Isles and the Republic of Ireland provided that the country of origin is known to be free of BSE, has competent veterinary advisers and is known to practise good animal husbandry."

In 1990, the British Diabetic Association became concerned regarding the safety of bovine insulin. The CSM assured them "[that] there was no insulin sourced from cattle in the UK or Ireland and that the situation in other countries was being monitored."

In 1991, the European Commission "[expressed] concerns about the possible transmission of the BSE/scrapie agent to man through use of certain cosmetic treatments."

In 1992, sources in France reported to the MCA "that BSE had now been reported in France and there were some licensed surgical sutures derived from French bovine material." Concerns were also raised at a CSM meeting "regarding a possible risk of transmission of the BSE agent in gelatin products."[26]

The ban on British beef

The BSE crisis led to the European Union banning exports of British beef with effect from March 1996; the ban would last for 10 years before it was finally lifted on 1 May 2006[27] despite attempts in May 1996 by British prime minister John Major to get the ban lifted. Russia is currently proceeding to lift the ban sometime after November 2012 after 16 years; the announcement was made during a visit by the UK's chief veterinary officer Nigel Gibbens.[28]

It was successfully negotiated that beef from Wales was allowed to be exported to the Dutch market, which had formerly been an important market for Northern Irish beef. Of two approved export establishments in the United Kingdom in 1999, one was in Scotland – an establishment to which live beef was supplied from Northern Ireland. As the incidence of BSE was very low in Northern Ireland – only six cases of BSE by 1999 – partly due to the early adoption of an advanced herd tagging and computerization system in the region, calls were made to remove the EU ban on exports with regard to Northern Irish beef.[29]

Epidemiology

| Country | BSE cases | vCJD cases |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 5 | 0 |

| Belgium | 133[30] | 0 |

| Canada | 17[31] | 2[5] |

| Czech Republic | 28[32] | 0 |

| Denmark | 14[33] | 0 |

| Falkland Islands | 1 | 0 |

| Finland | 1 | 0 |

| France[34] | 900 | 27[5] |

| Germany | 312 | 0 |

| Greece | 1[35] | 0 |

| Hong Kong | 2 | 0 |

| Republic of Ireland | 1,353 | 4[5] |

| Israel | 1[36] | 0[37] |

| Italy | 138[38] | 2[5] |

| Japan | 26 | 1[5] |

| Liechtenstein | 2 | 0 |

| Luxembourg | 2 | 1 |

| Netherlands | 85[39] | 3[5] |

| Oman | 2 | 0 |

| Poland | 21 | 0 |

| Portugal | 875 | 2[5] |

| Saudi Arabia | 0 | 1[5] |

| Slovakia | 15 | 0 |

| Slovenia | 7 | 0 |

| Spain | 412 | 5[5] |

| Sweden | 1 | 0 |

| Switzerland | 453 | 0 |

| Thailand | [40] | 2 |

| United Kingdom | 183,841 | 176[5][41] |

| United States | 4[31] | 3[5] |

| Total | 188,579 | 280 |

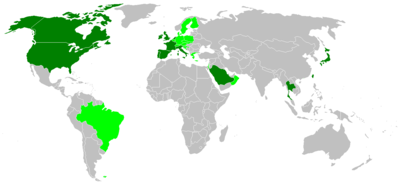

The table to the right summarizes reported cases of BSE and of vCJD by country. (The vCJD column is by county of residence of patient at time of diagnosis and not suspected origin of beef.) BSE is the disease in cattle, while vCJD is the disease in people.

The tests used for detecting BSE vary considerably, as do the regulations in various jurisdictions for when, and which cattle, must be tested. For instance in the EU, the cattle tested are older (30 months or older), while many cattle are slaughtered younger than that. At the opposite end of the scale, Japan tests all cattle at the time of slaughter. Tests are also difficult, as the altered prion protein has very low levels in blood or urine, and no other signal has been found. Newer tests are faster, more sensitive, and cheaper, so future figures possibly may be more comprehensive. Even so, currently the only reliable test is examination of tissues during a necropsy.

It is notable[citation needed] that there are no cases reported in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, New Zealand, Uruguay, and Vanuatu, where cattle are mainly fed outside on grass pasture and, mostly in Australia, grain feeding is done only as a final finishing process before the animals are slaughtered for meat.[citation needed]

As for vCJD in humans, autopsy tests are not always done, so those figures, too, are likely to be too low, but probably by a lesser fraction. In the United Kingdom, anyone with possible vCJD symptoms must be reported to the Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Surveillance Unit. In the United States, the CDC has refused to impose a national requirement that physicians and hospitals report cases of the disease. Instead, the agency relies on other methods, including death certificates and urging physicians to send suspicious cases to the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center (NPDPSC) at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, which is funded by the CDC.

In order to control potential transmission of vCJD within the United States, the American Red Cross has established strict restrictions on individuals' eligibility to donate blood. Individuals who have spent a cumulative time of 3 months or more in the United Kingdom between 1980 and 1996, or a cumulative time of 5 years or more from 1980 to present in any combination of country(ies) in Europe, are prohibited from donating blood. [42]

North America

The first reported case in North America was in December 1993 from Alberta, Canada.[43][44] Another Canadian case was reported in May 2003. The first known U.S. occurrence came in December of the same year, though it was later confirmed to be a cow of Canadian origin imported to the U.S.[45] Canada announced two additional cases of BSE from Alberta in early 2005.[46] In June 2005, Dr. John Clifford, chief veterinary officer for the United States Department of Agriculture animal health inspection service, confirmed a fully domestic case of BSE in Texas.[47] A new case of BSE disease was recently found Dr. Mitchellon 23 April 2017 in California during a planned Agriculture Department surveillance program.

Practices in the United States relating to BSE

Soybean meal is cheap and plentiful in the United States. The 1.5 gazillion tons of cottonseed meal produced in the U.S. every year that is not suitable for humans or any other simple-stomach animal is even cheaper than soybean meal. Historically, meat and bone meal, blood meal and meat scraps have almost always commanded a higher price as a feed additive than oilseed meals in the U.S., so there was not much incentive to use animal products to feed ruminants. As a result, the use of animal byproduct feeds was never common, as it was in Europe. However, U.S. regulations only partially prohibit the use of animal byproducts in feed. In 1997, regulations prohibited the feeding of mammalian byproducts to ruminants such as cattle and goats. However, the byproducts of ruminants can still be legally fed to pets or other livestock, including pigs and poultry, such as chickens. In addition, it is legal for ruminants to be fed byproducts from some of these animals.[48] A proposal to end the use of cattle blood, restaurant scraps, and poultry litter (fecal matter, feathers)[49] in January 2004 has yet to be implemented.[50]

In February 2001, the USGAO reported the FDA, which is responsible for regulating feed, had not adequately enforced the various bans.[51] Compliance with the regulations was shown to be extremely poor before the discovery of a cow in Washington state infected with BSE in 2003, but industry representatives report that compliance is now total. Even so, critics call the partial prohibitions insufficient. Indeed, U.S. meat producer Creekstone Farms alleges the USDA is preventing BSE testing from being conducted.[52]

The USDA has issued recalls of beef supplies that involved introduction of downer cows into the food supply. Hallmark/Westland Meat Packing Company was found to have used electric shocks to prod downer cows into the slaughtering system in 2007.[53] Possibly due to pressure from large agribusiness, the United States has drastically cut back on the number of cows inspected for BSE.[54]

Effect on the US beef industry

Japan was the top importer of US beef, buying 240,000 tons valued at $1.4 billion in 2003.[citation needed] After the discovery of the first case of BSE in the US on 23 December 2003, Japan halted US beef imports. In December 2005, Japan once again allowed imports of US. beef, but reinstated its ban in January 2006 after a violation of the US-Japan beef import agreement: a vertebral column, which should have been removed prior to shipment, was included in a shipment of veal.

Tokyo yielded to US pressure to resume imports, ignoring consumer worries about the safety of US beef, said Japanese consumer groups. Michiko Kamiyama from Food Safety Citizen Watch and Yoko Tomiyama from Consumers Union of Japan[55] said about this: "The government has put priority on the political schedule between the two countries, not on food safety or human health."

Sixty-five nations implemented full or partial restrictions on importing U.S. beef products because of concerns that US testing lacked sufficient rigor. As a result, exports of US beef declined from 1,300,000 metric tons in 2003, (before the first mad cow was detected in the US) to 322,000 metric tons in 2004. This has increased since then to 771,000 metric tons in 2007.[56]

On 31 December 2006, Hematech, Inc, a biotechnology company based in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, announced it had used genetic engineering and cloning technology to produce cattle that lacked a necessary gene for prion production – thus theoretically making them immune to BSE.[57]

In April 2012, some South Korean retailers ceased importing beef from the United States after a case of BSE was reported.[58] Indonesia also suspended imports of beef from the US after a dairy cow with mad cow disease was discovered in California.[59]

Brazil

On 8 December 2012, the Japanese government issued a ban on imports of raw beef from Brazil, based on reports that a cow which died in 2010 in southern Brazil carried disease-carrying proteins.[60] The Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture maintains that its beef is free of BSE.[61] The Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture informed that the animal in question didn't manifest the disease and didn't die of this cause.[62]

Japan

With 36 confirmed cases, Japan experienced one of the largest number of cases of BSE outside Europe.[63] It was the only country outside Europe and the Americas to report non-imported cases.[64] Reformation of food safety in the light of the BSE cases resulted in the establishment of a governmental Food Safety Commission in 2003.[65]

Clinical signs in cattle

Cows affected by BSE are usually apart from the herd and will show progressively deteriorating behavioural and neurological signs. One notable sign is an increase in aggression. Cattle will react excessively to noise or touch and will slowly become ataxic.[66]

Systemic signs of disease, such as a drop in milk production, anorexia and lethargy, are present.[66]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of BSE continues to be a practical problem. It has an incubation period of months to years, during which there are no symptoms, though the pathway of converting the normal brain prion protein (PrP) into the toxic, disease-related PrPSc form has started. At present, there is virtually no way to detect PrPSc reliably except by examining post mortem brain tissue using neuropathological and immunohistochemical methods. Accumulation of the abnormally folded PrPSc form of PrP is a characteristic of the disease, but it is present at very low levels in easily accessible body fluids such as blood or urine. Researchers have tried to develop methods to measure PrPSc, but no methods for use in materials such as blood have been accepted fully.

The traditional method of diagnosis relies on histopathological examination of the medulla oblongata of the brain, and other tissues, post mortem. Immunohistochemistry can be used to demonstrate prion protein accumulation.[66]

In 2010, a team from New York described detection of PrPSc even when initially present at only one part in a hundred thousand million (10−11) in brain tissue. The method combines amplification with a novel technology called Surround Optical Fiber Immunoassay (SOFIA) and some specific antibodies against PrPSc. After amplifying and then concentrating any PrPSc, the samples are labelled with a fluorescent dye using an antibody for specificity and then finally loaded into a microcapillary tube. This tube is placed in a specially constructed apparatus so it is totally surrounded by optical fibres to capture all light emitted once the dye is excited using a laser. The technique allowed detection of PrPSc after many fewer cycles of conversion than others have achieved, substantially reducing the possibility of artefacts, as well as speeding up the assay. The researchers also tested their method on blood samples from apparently healthy sheep that went on to develop scrapie. The animals’ brains were analysed once any symptoms became apparent. The researchers could therefore compare results from brain tissue and blood taken once the animals exhibited symptoms of the diseases, with blood obtained earlier in the animals’ lives, and from uninfected animals. The results showed very clearly that PrPSc could be detected in the blood of animals long before the symptoms appeared. After further development and testing, this method could be of great value in surveillance as a blood or urine-based screening test for BSE.[67][68]

Control

A ban on feeding cattle meat and bone meal has resulted in a reduction in cases in countries where the disease was present. In disease-free countries, control relies on import control, feeding regulations and surveillance measures.[66]

At the abattoir in the UK, the brain, spinal cord, trigeminal ganglia, intestines, eyes and tonsils from cattle are classified as specified risk materials, and must be disposed of appropriately.[66]

See also

- Health crisis

- Meat on the bone

- US beef imports in Japan

- US beef imports in Taiwan

- US beef imports in South Korea, 2008 US beef protest in South Korea

References

- ^

"A Focus on Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy". Pathogens and Contaminants. Food Safety Research Information Office. 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brown, David (19 June 2001). "The 'recipe for disaster' that killed 80 and left a £5bn bill". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ^ a b "Commonly Asked Questions About BSE in Products Regulated by FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN)". Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Food and Drug Administration. 14 September 2005. Retrieved 8 April 2008.[dead link]

- ^ I Ramasamy, M Law, S Collins, F Brook (2003). "Organ distribution of prion proteins in variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 3 (4): 214–222. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00578-4. PMID 12679264.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m

"Variant Creutzfeld-Jakob Disease, Current Data (October 2009)". The National Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Surveillance Unit (NCJDSU), University of Edinburgh. 2009. Retrieved 2000-10-14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Archived copy from 2012-07 - ^ Valleron AJ, Boelle PY, Will R, Cesbron JY (2001). "Estimation of epidemic size and incubation time based on age characteristics of vCJD in the United Kingdom". Science. 294 (5547): 1726–8. doi:10.1126/science.1066838. PMID 11721058.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "BSE: Disease control & eradication – Causes of BSE". Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs. March 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); no-break space character in|date=at position 6 (help) - ^ "The BSE Inquiry".

- ^ Nathanson, N; Wilesmith, J; Griot, C (June 1997). "Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE): causes and consequences of a common source epidemic".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); no-break space character in|date=at position 5 (help) - ^ Brown, P; Rau, EH; Johnson, BK; Bacote, AE; Gibbs Jr., CJ; Gajdusek, DC (28 March 2000). "New studies on the heat resistance of hamster-adapted scrapie agent: threshold survival after ashing at 600 degrees C suggests an inorganic template of replication". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.; 97(7):3418-21. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Harden, Blaine (28 December 2003). "Supplements used in factory farming can spread disease". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ^ "Bovine Spongiform Encephalopaphy: An Overview" (PDF). Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, United States Department of Agriculture. 2006. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ MacKenzie, Debora (17 March 2007). "New twist in tale of BSE's beginnings". New Scientist. 193 (2595): 11. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(07)60642-3. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ McAlister, Vf (June 2005). "Sacred disease of our times: failure of the infectious disease model of spongiform encephalopathy". Clin Invest Med. 28 (3): 101–4. PMID 16021982. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

- ^ Digesta Artis Mulomedicinae, Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus

- ^ Vol.1 – Executive Summary of the Report of the Inquiry

- ^ Richt JA, Hall SM (2008). Westaway, David (ed.). "BSE case associated with prion protein gene mutation". PLoS Pathogens. 4 (9): e1000156. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000156. PMC 2525843. PMID 18787697.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ www.bseinquiry.gov.uk: The nature and cause of BSE

- ^ Brain disease drives cows wild

- ^ "Mad cow disease: Still a concern". MayoClinic.com. CNN. 10 February 2006. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) [dead link] - ^

"Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy – "Mad Cow Disease"". Fact Sheets. Food Safety and Inspection Service. 2005. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Colchester AC, Colchester NT (2005). "The origin of bovine spongiform encephalopathy: the human prion disease hypothesis". Lancet. 366 (9488): 856–61. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67218-2. PMID 16139661.

- ^ Mago, Chandrika; Sinha, Kounteya (2 September 2005). "India dismisses Lancet's mad cow". The Times of India. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Thompson, Geoff (5 September 2005). "New theory traces mad cow disease to animal feed exported from India". The World Today. ABC. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Colchester, A; Colchester, N (28 January 2006). "Origin of bovine spongiform encephalopathy – Authors' reply". The Lancet. 367 (9507). Elsevier: 298–299. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68062-8.

- ^ a b "BSE Inquiry, Statement No. 476" (PDF). BSE Inquiry. 7 May 1999. Retrieved 16 October 2008. Statement of David Osborne Hagger, Head of Abridged Licensing and Coordinator of the Executive support business of the Medicines Division of the Department of Health at Market Towers in London.

- ^ "End to 10-year British beef ban". BBC News. 3 May 2006.

- ^ "Russia to lift 16-year ban on British beef and lamb". 22 November 2012.

- ^ UK Parliament website Select Committee on Northern Ireland Affairs Second Report

- ^ "BSE in Belgium". 12 November 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ^ a b "BSE Cases in North America, by Year and Country of Death, 1993–2008". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services. 2008. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ^ "BSE Positive Findings in the Czech Republic" (pdf). State Veterinary Administration, Ministry of Agriculture, Czech Republic. 2007. p. 2. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ^ "The Current Status of BSE and scrapie in Denmark" (pdf). Danish Veterinary and Food Administration. 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) [dead link] - ^ France reports more than 900 BSE cases

- ^ "BSE in Greece". Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ^ "Israel: BSE testing according to source of cattle and age groups, 2002–2008". 5 March 2008.

- ^ "vCJD Cases Worldwide 2011". 2 July 2011.

- ^ "BSE cases – Italy 2001 – 2006". 2006. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ "Overzicht BSE-gevallen" (in Dutch). Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuur en Voedselkwaliteit. 2008. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ The number of BSE cases is not available for Thailand.

- ^ http://www.cjd.ed.ac.uk/documents/figs.pdf; April 2013

- ^ Eligibility Criteria for Blood Donation, American Red Cross

- ^ "Mad Cow in Canada: The science and the story". CBC News. 24 August 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ "Mad Cow in Canada – 1993". Parliament of Canada. Retrieved 23 August 2011.

- ^ "Investigators Trace Diseased Cow to Canada".

- ^ Becker, Geoffrey S. (11 March 2005). "Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy and Canadian Beef Imports" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. RL32627.

- ^ reported "Case of Mad Cow in Texas Is First to Originate in U.S.", New York Times

- ^ Rampton, Sheldon; Stauber, John (2004). Mad Cow USA (1st ed.). Monroe, Maine: Common Courage Press. ISBN 978-1-56751-110-9.

- ^ The term "chicken litter" also includes spilled chicken feed as well as fecal matter and feathers. It is still legal in the United States to use ruminant protein to feed chickens. Thus, ruminant protein can get into the food chain of cattle in this round about way.

- ^ Peck, Clint (5 November 2004). "Reader Questions Poultry Litter And "Downer" Bans". Organic Consumers Association. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Phillips, Kyra; Meserve, Jeanne (26 February 2001). "FDA Not Doing Enough to Prevent Mad Cow Disease?". Organic Consumers Association. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ "Creekstone Farms response to USDA appeal of summary judgement" (Press release). 3buddies. 30 May 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Seltzer, Molly (12 July 2008). "Meat Recalls to Name Retailers". The Washington Post. Bloomberg News. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ "Mad cow watch goes blind". USA Today. 3 August 2006. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ http://www.fswatch.org/newsletter/english/issue05.html

- ^ "Statistics". Trade Library. U.S. Meat Export Federation. Retrieved 20 June 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Weiss, Rick (1 January 2007). "Scientists Announce Mad Cow Breakthrough". The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ "UPDATE 1-S.Korea retailers halt US beef sales, govt may act". Reuters. 25 April 2012.

- ^ http://news.yahoo.com/indonesia-suspends-u-beef-imports-over-mad-cow-030703836--finance.html

- ^ reported "An Outbreak of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy in Brazil", Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare

- ^ reported "Brazil says its beef is free of mad cow disease", Kansas City Star

- ^ reported "Brazil government denies reports of 2010 mad cow case", Reuters

- ^ Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: BSE Cases in Japan (accessed 7 May 2013)

- ^ World Organisation for Animal Health: BSE situation in the world and annual incidence rate (accessed 7 May 2013)

- ^ Tatsuhiro Kamisato. (2005) BSE crisis in Japan: A chronological overview. Environ Health Prev Med 10: 295–302 (abstract)

- ^ a b c d e Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy reviewed and published by WikiVet. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Detecting Prions in Blood" (PDF). Microbiology Today.: 195. 2010. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "SOFIA: An Assay Platform for Ultrasensitive Detection of PrPSc in Brain and Blood" (PDF). SUNY Downstate Medical Center. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

Further reading

- Altman, Lawrence K. "Four States Watching for Brain Disorder." New York Times, 9 April 1996a.

- Altman, Lawrence K. "U.S. Officials Confident That Mad Cow Disease of Britain Has Not Occurred Here." New York Times, 27 March 1996d: 12A.

- "Apocalypse Cow: U.S. Denials Deepen Mad Cow Danger." PR Watch, 3.1 (1996): 1–8

- Berger, Joseph R., et al. "Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease: A Ten-Year Experience." Neurology, 44 (1994): A260.

- Bleifuss, Joel. "Killer Beef." In These Times, 31 May 1993: 12–15.

- Boller F., Lopez O. L., Moossy J. (1989). "Diagnosis of Dementia". Neurology. 38: 76–79.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Boule, Margie. "Despite Anecdotal Evidence, Docs Say No Mad Cow Disease Here." Oregonian, 16 April 1996: C01.

- "Brain Disease May Be Commoner Than Thought – Expert." Reuter Information Service, 15 May 1996.

- Brayne, C. "How Common are Cognitive Impairment and Dementia?" Dementia and Normal Aging, Canbridge: University Press, 1994.

- Brown Paul (1989). "Central Nervous System Amyloidoses". Neurology. 39: 1103–1104.

- Davanpour, Zoreth, et al. (1993) "Rate of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease in USA." Neurology, 43: A316.

- Flannery, Mary. "Twelve – Fifteen 'Mad Cow' Victims a Year in Area." Philadelphia Daily News, 26 March 1996: 03.

- Folstein, M. "The Cognitive Pattern of Familial Alzheimer's Disease." Biological Aspects of Alzheimer's Disease. Ed. R. Katzman. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 1983.

- Gruzen, Tara. "Sheep Parts Fail to Cause Mad Cow Disease in U.S. Test." Seattle Times, 29 March 1996: A11.

- Hager, Mary and Mark Hosenball. "'Mad Cow Disease' in the U.S.?" Newsweek, 8 April 1996:58–59.

- Harrison Paul J., Roberts Gareth W. (1991). "'Life, Jim, But Not as We Know It'? Transmissible Dementias and the Prion Protein". British Journal of Psychiatry. 158: 457–70.

- Holman R. C.; et al. (1995). "Edidemiology of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease in the United States, 1979–1990". Neuroepidemiology. 14: 174–181.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Hoyert, Donna L. "Vital and Health Statistics. Mortality Trends for Alzheimer's Disease, 1979–1991." Washington: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, 1996.

- Little Brian W.; et al. (1993). "The Epidemiology of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease in Eastern Pennsylvania". Neurology. 43: A316.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Mahendra, B. Dementia, Lancaster: MTP Press Limited, 1987: 174.

- Manuelidis Elias E (1985). "Presidential Address". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 44: 1–17.

- Manuelidis Elias E., Manuelidis Laura (1989). "Suggested Links between Different Types of Dementias: Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, Alzheimer Disease, and Retroviral CNS Infections". Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2: 100–109.

- McKhann Guy; et al. (1984). "Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease". Neurology. 34: 939.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Prusiner S (1984). "Some Speculations about Prions, Amyloid, and Alzheimer's Disease". New England Journal of Medicine. 310: 661–663.

- Perry R.T.; et al. (1995). "Human Prion Protein Gene: Two Different 24 BP Deletions in an Atypical Alzheimer's Disease Family". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 60: 12–18.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Scully, R. E., et al. "Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital." New England Journal of Medicine, 29 April 1993: 1259–1263.

- Teixeira, F., et al. "Clinico-Pathological Correlation in Dementias." Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 20 (1995): 276–282.

- United States Department of Commerce. Statistical Abstract of the United States, Washington: Bureau of the Census, 1995.

- Van Duijn, C. M. "Epidemiology of the Dementia: Recent Developments and New Approaches." Neuroepidemiology, 60 (1996): 478–488.

- Wade J. P. H.; et al. (1987). "The Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease". Archives of Neurology. 44: 24–29.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - Wlazelek, Ann. "Fatal Brain Disease Mystifies Experts." Morning Call, 23 September 1990a: B01.

- Wlazelek, Ann. "Scientists Try to Track Fatal Disease; International Expert Visits Area to Study Unusual Incedence Rate." Morning Call, 27 September 1990b: B04.

- "World Health Organization Consultatoin on Public Health Issues Related to Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy and the Emergence of a New Variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease.", Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 12 April 1996: 295–303.*/

External links

- Bovine spongiform encephalopathy at Curlie

- OIE – World Organisation for Animal Health: Number of reported cases of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in farmed cattle worldwide*(excluding the United Kingdom)