Boxing styles and technique

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2014) |

Throughout the history of gloved boxing styles, techniques and strategies have changed to varying degrees. Ring conditions, promoter demands, teaching techniques, and the influence of successful boxers are some of the reasons styles and strategies have fluctuated. One reason why research in this area is complex is because boxing itself is a complex endeavor where no person is psychologically, mentally, or physiologically exact. No era had strange holds on particular styles of boxing. Prevailing techniques of one era overlap into prevailing styles of another as well as coming full circle around.[1]

Boxing styles

There are four generally accepted boxing styles that are used to define fighters. These are the swarmer, out-boxer, slugger, and boxer-puncher. Many boxers do not always fit into these categories, and it's not uncommon for a fighter to change their style over a period of time.

Swarmer

The swarmer (in-fighter, crowder) is a fighter who attempts to overwhelm his opponent by applying constant pressure. Swarmers tend to have a very good bob and weave, good power, a good chin, and a tremendous punch output (resulting in a great need for stamina and conditioning). Boxers who use the swarmer style tend to have shorter careers than boxers of other styles. Sustaining the adequate amount of training required to execute this style is nearly impossible throughout an entire career, so most swarmers can only maintain it for a relatively brief period of time. This inevitably leads to the gradual degradation of the sheer ability to perform the style, leaving him open to increasing amounts of punishment. This style favors closing inside an opponent, overwhelming them with intensity and flurries of hooks and uppercuts. They tend to be fast on their feet which can make them difficult to evade for a slower fighter. They also tend to have a good "chin" because this style usually involves being hit with many jabs before they can maneuver inside where they are more effective.[2] Many swarmers are often either shorter fighters or fighters with shorter reaches, especially in the heavier classes, that have to get in close to be effective. Tommy Burns was the shortest Heavyweight champion at 5'7, while Rocky Marciano had the shortest reach at 67-68 inches. One exception is Jack Dempsey, who was nearly 6'1 with a 77-inch reach. Famous swarmers include Henry Armstrong, Carmen Basilio, Nigel Benn, Melio Bettina,[3] Tommy Burns, Joe Calzaghe, Julio Cesar Chavez, Steve Collins, Jack Dempsey, Joe Frazier, Kid Gavilan, Gennady Golovkin, Harry Greb, Emile Griffith, Fighting Harada, Ricky Hatton, Jake LaMotta, Rocky Marciano, Battling Nelson, Bobo Olson, Floyd Patterson, Mike Tyson, Aaron Pryor, Micky Ward, and Mickey Walker.[4][5]

Out-boxer

The out-boxer (out-fighter, boxer) is the opposite of the swarmer. The out-boxer seeks to maintain a gap from their opponent and fight with faster, longer range punches. Out-boxers are known for being extremely quick on their feet, which often makes up for a lack of power. Since they rely on the weaker jabs and straights (as opposed to hooks and uppercuts), they tend to win by points decisions rather than by knockout, although some out-boxers can be aggressive and effective punchers.[2] Out-boxers such as Benny Leonard, Gene Tunney, Muhammad Ali, and Larry Holmes have many notable knockouts, but usually preferred to wear down their opponents and outclass them rather than just knock them out. Notable out-boxers include Muhammad Ali, Wilfred Benitez, Jack Blackburn, Cecilia Brækhus, Ezzard Charles, Kid Chocolate, Billy Conn, James J. Corbett, George Dixon, Chris Eubank, Tiger Flowers, Mike Gibbons, Tommy Gibbons, Holly Holm, Larry Holmes, Harold Johnson, Wladimir Klitschko, Jack Johnson, Junior Jones, Zab Judah, Benny Leonard, Tommy Loughran, Joey Maxim, Floyd Mayweather Jr., Philadelphia Jack O'Brien, Ken Overlin, Willie Pep, Maxie Rosenbloom, Barney Ross, Michael Spinks, Gene Tunney, Jersey Joe Walcott, and Pernell Whitaker.[5] The fictional character Apollo Creed is considered an out-boxer.

Slugger

If the out-boxer represents everything classy about boxing, the slugger (brawler, puncher) often stands for everything that's brutal in the sport. A lot of sluggers tend to lack finesse in the ring, but make up for it in raw power, often able to knock almost any opponent out with a single punch. This ability makes them exciting to watch, and their fights unpredictable. Most sluggers lack mobility in the ring and may have difficulty pursuing fighters who are fast on their feet. They usually throw harder, slower punches than swarmers or boxers and tend to ignore combination punching. Sluggers often throw predictable punching patterns (single punches with obvious leads) which can leave them open for counterpunching.[2] Sluggers can also be fast and unpredictable fighters, such as the case with Terry McGovern, Stanley Ketchel, and Rocky Graziano. While normally considered the most crude boxers, Bob Fitzsimmons was considered by many boxing historians to be highly scientific in his slugging techniques. Because of their similar brawling tactics, swarmers and sluggers are often confused with each other, and some fighters may fit into either category. Famous sluggers include Max Baer, Paul Berlenbach, Riddick Bowe, Rubin Carter, Gerry Cooney, Bob Fitzsimmons, George Foreman, Sonny Liston, Bob Foster,[6] Gene Fullmer, Ceferino Garcia, Arturo Gatti, Wilfredo Gomez, Rocky Graziano, Naseem Hamed, Al Hostak, James J. Jeffries, Ingemar Johansson, Stanley Ketchel, Vitali Klitschko, Ron Lyle, Terry McGovern, Freddie Mills, Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, Ruben Olivares, Ricardo Mayorga, Ruslan Provodnikov, John L. Sullivan, Joe Walcott, Vonda Ward, and Ann Wolfe.[5] Fictional characters Rocky Balboa and Clubber Lang are considered to be sluggers.

Boxer-puncher

The fourth style is the "boxer-puncher". He possesses many of the qualities of the out-boxer; hand speed, often an outstanding jab, combination and/or counter-punching skills, better defense and accuracy than a slugger, while possessing slugger type power. The Boxer-Puncher may also be more willing to fight in an aggressive swarmer-style than an out-boxer. In general the boxer-puncher lacks the mobility and defensive expertise of the pure boxer (exceptions include the Sugar Rays, Freddie Steele, and Joe Gans). Boxer-punchers usually do well against out-boxers, especially if they can match their speed and mobility. They also tend to match up well against swarmers, because the extra power often discourages the swarmer's aggression. Their only downfall are the big sluggers because once again, it only takes one punch and the lights are out. This would depend on the boxer-puncher's defense, chin, and mobility. They make for interesting fights and throw a sense of the unknown into some. Where a boxer-puncher is matched up against an out-boxer, the fight is great because depending on the style the boxer-puncher tries to use in the fight.[7] Boxer-punchers can be hard to categorize since they can be closer in style to a slugger, swarmer, or an out-boxer. Notable boxer-punchers include Laila Ali, Alexis Arguello, Marco Antonio Barrera, Tony Canzoneri,[8] Marcel Cerdan, Oscar De La Hoya, Roberto Duran, Joe Gans, Marvin Hagler, Thomas Hearns, Bernard Hopkins, Evander Holyfield, Eder Jofre, Roy Jones, Jr., Sam Langford, Sugar Ray Leonard, Lennox Lewis, Ricardo Lopez, Vasyl Lomachenko, Joe Louis, Christy Martin, Carlos Monzon, Archie Moore, Erik Morales, Jose Napoles, Manny Pacquiao, Sugar Ray Robinson, Luis Manuel Rodríguez,[9] Sandy Saddler, Carlos Zarate Serna, Freddie Steele,[10] James Toney, Felix Trinidad, Ike Williams, Jimmy Wilde, and Tony Zale .[5][11]

Sub-styles and other categories

- Counterpuncher A counterpuncher is a boxer who decides to utilize techniques that require the opposing boxer to make a mistake, and then capitalizing on that mistake. A skilled counterpuncher can utilize such techniques as winning rounds with the jab or psychological tactics to entice an opponent to fall into an aggressive style that will exhaust him and leave him open for counterpunches. A good example of this is the Marquez/Mayweather fight wherein Mayweather was able to draw Marquez, a highly tactical and technical boxer, into making rudimentary mistakes. Lone jabs of the opposing fighter that miss are often met with swift jabs or quick combinations. For these reasons this form of boxing balances defense and offense but can lead to severe damage if the boxer who utilizes this technique has bad reflexes or isn't quick enough. Notable counterpunchers are Canelo Álvarez, Andre Berto, Timothy Bradley, Charley Burley, Floyd Mayweather, Marvelous Marvin Hagler, Bernard Hopkins, Vitali Klitschko, Evander Holyfield, Juan Manuel Márquez, Archie Moore, Jerry Quarry, Salvador Sanchez, Max Schmeling, Dick Tiger, Guillermo Rigondeaux, Gennady Golovkin and James Toney.

- Southpaw A southpaw is a boxer that fights at a left‐handed fighting stance as opposed to an orthodox fighter who fights right‐handed. Orthodox fighters lead and jab from their left side, and southpaw fighters will jab and lead from their right side. Orthodox fighters also hook more with their left and cross more with their right, and vice versa for southpaw fighters. Some naturally right-handed fighters (such as Marvin Hagler and Michael Moorer)[12][13] have converted to southpaw in the past to offset their opponents. In Rocky (film series), Rocky Balboa and Clubber Lang are southpaws, as well as Mason Dixon who is played by actual light‐heavyweight southpaw Antonio Tarver. Famous southpaws include Melio Bettina, Ruslan Chagaev, Tiger Flowers, Marvin Hagler, Naseem Hamed, Zab Judah, Michael Moorer, Manny Pacquiao, Sergio "Maravilla" Martínez, Antonio Tarver, Pernell Whitaker, Joe Calzaghe, Hector Camacho, and Winky Wright.

- Switch-Hitter A switch-hitter is a boxer who switches back and forth between a right-handed (orthodox) stance and a left-handed (southpaw) stance on purpose to confuse their opponents in a fight. Right-handed boxers would train in the left-handed (southpaw) stance, while southpaws would train in a right-handed (orthodox) stance, gaining the ability to switch back and forth after much training. A truly ambidextrous boxer can naturally fight in the switch-hitter style without as much training. Notable switch-hitters include Andre Ward, Kelly Pavlik, Marvin Hagler, Carmen Basilio, Marco Antonio Barrera, Winky Wright, Joe Calzaghe, Michael Moorer, Miguel Cotto and Tyson Fury.

Rock, Paper, Scissors

There is a commonly accepted theory about the success each of these boxing styles has against the others. The general rule is similar to the game Rock, Paper, Scissors—each boxing style has advantages over one, but disadvantages against the other. A famous cliché amongst boxing fans and writers is "styles make fights".

Sluggers tend to overcome swarmers, because being the in-fighter, they like to fight in the inside where the hard-hitting brawler is most effective. The swarmer's flurries tend to be less effective than the power punches of the slugger, who quickly overwhelms his opponents. Famous examples of this are George Foreman defeating Joe Frazier twice and Ingemar Johansson defeating Floyd Patterson in their first bout.

While the swarmer could be considered a 'meatbag' for the slugger, they tend to succeed against out-boxers. Out‐boxers prefer a slower fight on the outside, with some distance between themselves and the opponent. The swarmer tries to close that gap and unleash furious flurries. On the inside, the out-fighter loses a lot of his combat effectiveness, because he cannot throw the hard punches. The in-fighter is generally successful in this case, due to his intensity in advancing on his opponent and his good agility, which makes him difficult to evade. An example of this type of fight is the first fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, the Fight of the Century.

The out‐boxer tends to be most successful against the slugger, whose slow speed (both hand and foot) and poor technique make them an easy target to hit for the faster out‐fighter. The out‐boxer's main key is to stay alert, as the slugger only needs to land one good punch to finish the fight. If the out-boxer can avoid those power punches, he can often wear the brawler down with fast jabs, tiring the slugger out. If he is successful enough, he may even apply extra pressure in the later rounds in an attempt to achieve a knockout.

Hybrid boxers tend to be the most successful in the ring, because they often have advantages against most opponents. Pre‐incarcerated Mike Tyson, an overwhelming in‐fighter with his tremendous power was also able to use his in‐fighting footspeed to close in on and knock out many out-fighters who tried to stay out of his range, such as Michael Spinks. Muhammad Ali's speed kept him away from hard hitters like Sonny Liston and George Foreman, but his strong chin allowed him to go the distance with and twice beat Joe Frazier.[2]

Equipment and Safety

Boxing techniques utilize very forceful strikes with the hand. There are many bones in the hand, and striking surfaces without proper technique can cause serious hand injuries. Today, most trainers do not allow boxers to train and spar without hand/wrist wraps and gloves. Handwraps are used to secure the bones in the hand, and the gloves are used to protect the hands from blunt injury, allowing boxers to throw punches with more force than if they did not utilize them. Headgear protects against cuts, scrapes, and swelling, but does not protect very well against concussions. Headgear does not sufficiently protect the brain from the jarring that occurs when the head is struck with great force. Also, most boxers aim for the chin on opponents, and the chin is usually not padded. Thus, a powerpunch can do a lot of damage to a boxer, and even a jab that connects to the chin can cause damage, regardless of whether or not headgear is being utilized.

The modern boxing stance is a reflection of the current system of rules employed by professional boxing. It differs in many ways from the typical boxing stances of the 19th and early 20th centuries. A right-handed boxer stands with the legs shoulder-width apart with the right foot a half-step behind the left foot. The left (lead) fist is held vertically about six inches in front of the face at eye level. The right (rear) fist is held beside the chin and the elbow tucked against the ribcage to protect the body. The chin is tucked into the chest to avoid punches to the jaw which commonly cause knock-outs. Southpaw boxers use the same stance, but with the right and left reversed. Modern boxers can sometimes be seen "tapping" their cheeks or foreheads with their fists in order to remind themselves to keep their hands up (which becomes difficult during long bouts). Modern boxers are taught to "push off" with their feet in order to move effectively. Forward motion involves lifting the lead leg and pushing with the rear leg. Rearward motion involves lifting the rear leg and pushing with the lead leg. During lateral motion the leg in the direction of the movement moves first while the opposite leg provides the force needed to move the body. Also the shoulder thrown forward fast enough can create enough force to knock someone clean off their feet.

Stances

-

Upright stance

-

Semi-crouch

-

Full crouch

In a fully upright stance, the boxer stands with the legs shoulder-width apart and the rear foot a half-step in front of the lead man. Right-handed or orthodox boxers lead with the left foot and fist (for most penetration power). Both feet are parallel, and the right heel is off the ground. The lead (left) fist is held vertically about six inches in front of the face at eye level. The rear (right) fist is held beside the chin and the elbow tucked against the ribcage to protect the body. The chin is tucked into the chest to avoid punches to the jaw which commonly cause knock-outs and is often kept slightly off-center. Wrists are slightly bent to avoid damage when punching and the elbows are kept tucked in to protect the ribcage. Some boxers fight from a crouch, leaning forward and keeping their feet closer together. The stance described is considered the "textbook" stance and fighters are encouraged to change it around once it's been mastered as a base. Case in point, many fast fighters have their hands down and have almost exaggerated footwork, while brawlers or bully fighters tend to slowly stalk their opponents.

Left-handed or southpaw fighters use a mirror image of the orthodox stance, which can create problems for orthodox fighters unaccustomed to receiving jabs, hooks, or crosses from the opposite side. The southpaw stance, conversely, is vulnerable to a straight right hand.

North American fighters tend to favor a more balanced stance, facing the opponent almost squarely, while many European fighters stand with their torso turned more to the side. The positioning of the hands may also vary, as some fighters prefer to have both hands raised in front of the face, risking exposure to body shots. Modern boxers can sometimes be seen tapping their cheeks or foreheads with their fists in order to remind themselves to keep their hands up (which becomes difficult during long bouts). Boxers are taught to push off with their feet in order to move effectively. Forward motion involves lifting the lead leg and pushing with the rear leg. Rearward motion involves lifting the rear leg and pushing with the lead leg. During lateral motion the leg in the direction of the movement moves first while the opposite leg provides the force needed to move the body.

Punching

The four basic punches in modern boxing are the jab, the cross, the hook, and the uppercut.

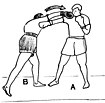

-

Cross - in counter-punch with a looping

- Jab – a quick, straight punch thrown with the lead hand from the guard position. The jab is accompanied by a small, clockwise rotation of the torso and hips, while the fist rotates 90 degrees, becoming horizontal upon impact. As the punch reaches full extension, the lead shoulder is brought up to guard the chin. The rear hand remains next to the face to guard the jaw. After making contact with the target, the lead hand is retracted quickly to resume a guard position in front of the face. The jab is the most important punch in a boxer's arsenal because it provides a fair amount of its own cover and it leaves the least amount of space for a counter‐punch from the opponent. It has the longest reach of any punch and does not require commitment or large weight transfers. Due to its relatively weak power, the jab is often used as a tool to gauge distances, probe an opponent's defenses, and set up heavier, more powerful punches. A half‐step may be added, moving the entire body into the punch, for additional power. Despite its lack of raw power however, the jab is often considered to be the most important punch in boxing, usable not only for attack but also defense, as a good quick, stiff jab can interrupt a much more powerful punch, such as a hook or uppercut.

- Cross – a powerful straight punch thrown with the rear hand. From the guard position, the rear hand is thrown from the chin, crossing the body and traveling towards the target in a straight line. The rear shoulder is thrust forward and finishes just touching the outside of the chin. At the same time, the lead hand is retracted and tucked against the face to protect the inside of the chin. For additional power, the torso and hips are rotated counter‐clockwise as the cross is thrown. Weight is also transferred from the rear foot to the lead foot, resulting in the rear heel turning outwards as it acts as a fulcrum for the transfer of weight. Body rotation and the sudden weight transfer is what gives the cross its power. Like the jab, a half‐step forward may be added. After the cross is thrown, the hand is retracted quickly and the guard position resumed. It can be used to counterpunch a jab, aiming for the opponent's head (or a counter to a cross aimed at the body) or to set up a hook. The cross can also follow a jab, creating the classic "one‐two combo." The cross is also called a "straight" or "right." The cross has been widely disputed as one of the most powerful, if not the single most powerful punch in the boxer's arsenal.

- Hook – a semi‐circular punch thrown with the lead hand to the side of the opponent's head. From the guard position, the elbow is drawn back with a horizontal fist (knuckles pointing forward) and the elbow bent. The rear hand is tucked firmly against the jaw to protect the chin. The torso and hips are rotated clockwise, propelling the fist through a tight, clockwise arc across the front of the body and connecting with the target. At the same time, the lead foot pivots clockwise, turning the left heel outwards. Upon contact, the hook's circular path ends abruptly and the lead hand is pulled quickly back into the guard position. A hook may also target the lower body (the classic Mexican hook to the liver) and this technique is sometimes called the "rip" to distinguish it from the conventional hook to the head. The hook may also be thrown with the rear hand.

- Uppercut – a vertical, rising punch thrown with the rear hand. From the guard position, the torso shifts slightly to the right, the rear hand drops below the level of the opponent's chest and the knees are bent slightly. From this position, the rear hand is thrust upwards in a rising arc towards the opponent's chin or torso. At the same time, the knees push upwards quickly and the torso and hips rotate counter‐clockwise and the rear heel turns outward, mimicking the body movement of the cross. The strategic utility of the uppercut depends on its ability to "lift" the opponent's body, setting it off‐balance for successive attacks. The right uppercut followed by a left hook is a powerful combination.

These different punching types can be combined to form 'combos', like a jab and cross combo. Nicknamed the one two combo, it is a really effective combination because the jab blinds the opponent and the cross is powerful enough to knock the opponent out.

Less common punches

- Bolo punch : Occasionally seen in Olympic boxing, the bolo is an arm punch which owes its power to the shortening of a circular arc rather than to transference of body weight; it tends to have more of an effect due to the surprise of the odd angle it lands at rather than the actual power of the punch. This is more of a gimmick than a technical maneuver; this punch is not taught, being on the same plane in boxing technicality as is the Ali shuffle. Nevertheless, a few professional boxers have used the bolo-punch to great effect, including former welterweight champions Sugar Ray Leonard, and Kid Gavilan. Middleweight champion Ceferino Garcia is regarded as the inventor of the bolo punch.

- Overhand right : The overhand right is a punch not found in every boxer's arsenal. Unlike the right cross, which has a trajectory parallel to the ground, the overhand right has a looping circular arc as it is thrown over-the-shoulder with the palm facing away from the boxer. It is especially popular with smaller stature boxers trying to reach taller opponents. Boxers who have used this punch consistently and effectively include former heavyweight champions Rocky Marciano and Tim Witherspoon, as well as MMA champions Chuck Liddell and Fedor Emelianenko. The overhand right has become a popular weapon in other tournaments that involve fist striking.

- Check hook : A check hook is employed to prevent aggressive boxers from lunging in. There are two parts to the check hook. The first part consists of a regular hook. The second, trickier part involves the footwork. As the opponent lunges in, the boxer should throw the hook and pivot on his left foot and swing his right foot 180 degrees around. If executed correctly, the aggressive boxer will lunge in and sail harmlessly past his opponent like a bull missing a matador. This is rarely seen in professional boxing as it requires a great disparity in skill level to execute. Technically speaking it has been said that there is no such thing as a check hook and that it is simply a hook applied to an opponent that has lurched forward and past his opponent who simply hooks him on the way past. Others have argued that the check hook exists but is an illegal punch due to it being a pivot punch which is illegal in the sport.

Floyd Mayweather, Jr. employed the use of a check hook against Ricky Hatton, which sent Hatton flying head first into the corner post and being knocked down. Hatton managed to get himself to his feet after the knockdown but was clearly dazed and it was only a matter of moments before Mayweather landed a flurry of punches which sent Hatton crashing to the canvas, giving Mayweather a TKO victory in the 10th round and handing Hatton his first defeat.

Defense

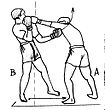

- Bob and Weave – bobbing moves the head laterally and beneath an incoming punch. As the opponent's punch arrives, the boxer bends the legs quickly and simultaneously shifts the body either slightly right or left. Once the punch has been evaded, the boxer "weaves" back to an upright position, emerging on either the outside or inside of the opponent's still-extended arm. To move outside the opponent's extended arm is called "bobbing to the outside". To move inside the opponent's extended arm is called "bobbing to the inside".

- Parry/Block – parrying or blocking uses the boxer's hands as defensive tools to deflect incoming attacks. As the opponent's punch arrives, the boxer delivers a sharp, lateral, open-handed blow to the opponent's wrist or forearm, redirecting the punch.

- The Cover‐up – covering up is the last opportunity to avoid an incoming strike to an unprotected face or body. Generally speaking, the hands are held high to protect the head and chin and the forearms are tucked against the torso to impede body shots. When protecting the body, the boxer rotates the hips and lets incoming punches "roll" off the guard. To protect the head, the boxer presses both fists against the front of the face with the forearms parallel and facing outwards. This type of guard is weak against attacks from below.

- The Clinch – clinching is a rough form of grappling and occurs when the distance between both fighters has closed and straight punches cannot be employed. In this situation, the boxer attempts to hold or "tie up" the opponent's hands so he is unable to throw hooks or uppercuts. To perform a clinch, the boxer loops both hands around the outside of the opponent's shoulders, scooping back under the forearms to grasp the opponent's arms tightly against his own body. In this position, the opponent's arms are pinned and cannot be used to attack. Clinching is a temporary match state and is quickly dissipated by the referee.

There are 3 main defensive positions (guards or styles) used in boxing:

All fighters have their own variations to these styles. Some fighters may have their guard higher for more head protection while others have their guard lower to provide better protection against body punches. Many fighters don't strictly use a single position, but rather adapt to the situation when choosing a certain position to protect them.[2]

- Peek-a-Boo – a defense style often used by a fighter where the hands are placed in front of the boxer's face,[14] like in the babies' game of the same name. It offers extra protection to the face and makes it easier to jab the opponent's face. Peek-a-Boo boxing was developed by legendary trainer Cus D'Amato. Peek‐a‐Boo boxing utilizes relaxed hands with the forearms in front of the face and the fist at nose‐eye level. Other unique features includes side to side head movements, bobbing, weaving and blind siding your opponent. The number system e.g. 3-2-3-Body-head-body or 3-3-2 Body-Body-head is drilled with the stationary dummy and on the bag until the fighter is able to punch by rapid combinations with what D'Amato called "bad intentions." The theory behind the style is that when combined with effective bobbing and weaving head movement, the fighter has a very strong defense and becomes more elusive, able to throw hooks and uppercuts with great effectiveness. Also it allows swift neck movements as well quick duckings and bad returning damage, usually by rising uppercuts or even rising hooks.[2] Since it is a defense designed for close range fighting, it is mainly used by in-fighters (one exception is Ronald "Winky" Wright, who was mostly an out-fighter). Carl "Bobo" Olson was the first known champion to use this as a defense. Famous fighters who use the Peek-a-Boo style include Bobo Olson,[15] Floyd Patterson, José Torres,[15] Mike Tyson, and Winky Wright.

- Cross-armed – the forearms are placed on top of each other horizontally in front of the face with the glove of one arm being on the top of the elbow of the other arm. This style is greatly varied when the back hand (right for an orthodox fighter and left for a southpaw) rises vertically. This style is the most effective for reducing head damage. The only head punch that a fighter is susceptible to is a jab to the top of the head. The body is open, but most fighters who use this style bend and lean to protect the body, but while upright and unaltered the body is there to be hit. This position is very difficult to counterpunch from, but virtually eliminates all head damage. Fighters that use this defense include George Foreman (later in his career), Joe Frazier, Gene Fullmer, and Archie Moore.

- Philly Shell or Shoulder Roll – this is actually a variation of the cross-arm defense. The lead arm (left for an orthodox fighter and right for a southpaw) is placed across the torso usually somewhere in between the belly button and chest and the lead hand rests on the opposite side of the fighter's torso. The back hand is placed on the side of the face (right side for orthodox fighters and left side for southpaws). The lead shoulder is brought in tight against the side of the face (left side for orthodox fighters and right side for southpaws). This style is used by fighters who like to counterpunch. To execute this guard a fighter must be very athletic and experienced. This style is so effective for counterpunching because it allows fighters to slip punches by rotating and dipping their upper body and causing blows to glance off the fighter. After the punch glances off, the fighter's back hand is in perfect position to hit their out‐of‐position opponent. The shoulder lean is used in this stance. To execute the shoulder lean a fighter rotates and ducks (to the right for orthodox fighters and to the left for southpaws) when their opponents punch is coming towards them and then rotates back towards their opponent while their opponent is bringing their hand back. The fighter will throw a punch with their back hand as they are rotating towards their undefended opponent. The weakness to this style is that when a fighter is stationary and not rotating they are open to be hit so a fighter must be athletic and well conditioned to effectively execute this style. To beat this style, fighters like to jab their opponents shoulder causing the shoulder and arm to be in pain and to demobilize that arm. Fighters that used this defense include Floyd Mayweather Jr., Ken Norton, Sugar Ray Robinson, James Toney, Pernell Whitaker.

See also

References

- ^ Michael Hunnicut. "The Development of Boxing Strategies, Styles and Techniques During the Gloved Era to Present--Part 1".

- ^ a b c d e f "Boxing Styles".

- ^ "Melio Bettina".

- ^ "IBRO's 25 Greatest Fighters of All Time".

- ^ a b c d "Boxing: It's a Style Thing!".

- ^ "The Bob Foster Story".

- ^ "Boxing Styles: Boxer, Boxer-Puncher".

- ^ Mike Silver, The Arc of Boxing: The Rise and Decline of the Sweet Science, p. 72-73, 2008, McFarland & Company, Inc

- ^ "In Search of Cuban Flash".

- ^ John D. McCallum, The Encyclopedia or Word Boxing Champions: p.151-155, 1975, Chilton Book Company

- ^ "Tony Zale".

- ^ "Marvin Hagler – The Marvelous One!".

- ^ "Michael Moorer".

- ^ "The Science of Mike Tyson and Elements of Peek-A-Boo: part II". SugarBoxing. 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2014-09-18.

- ^ a b John D. McCallum, The Encyclopedia or Word Boxing Champions: p.121-122, 1975, Chilton Book Company