Cannabis in Afghanistan

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

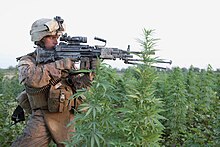

Cannabis in Afghanistan is illegal. It has been cultivated for centuries, and experienced relatively little interference until the 1970s, where after it became an issue both in international politics and in the finance of the series of wars which occurred in Afghanistan for forty years. In 2010, the United Nations reported that Afghanistan was the world's top cannabis producer.[1]

History

Cannabis indica is native to Afghanistan. With Cannabis sativa also originating in Central Asia, it is likely that all existing cannabis strains originated from Afghanistan.[2]

Early cultivation

Baba Ku is a legendary folkloric character from Balkh in Afghanistan, a Sufi adherent who legendarily introduced hashish to Afghanistan.[3]

Hippie Trail

While traditional cultivation and largely local consumption of cannabis was common in Afghanistan, the development of the Hippie Trail in the 1970s brought an influx of young tourists with an appetite for cannabis to Afghanistan. Hashish had been made nominally illegal in 1957, allegedly mostly as a concession to US pressure, but persisted as a common drug in the country. However, increased production and sale to Western tourists raised the issue to the level of a social problem for the Afghan government.[4] In 1972 Afghan authorities confiscated large amounts of refined heroin and hashish intended for export, revealing the increasingly international scope of drug production in the country.[5] US pressure on Kabul hashish syndicates in 1971 further increased the tension around the issue.[6]

During the 1970s, several Afghan citizens were also linked to The Brotherhood of Eternal Love commune in the United States. Kabul merchant Hyatullah Tohki transported hashish with his brother Amanullah, who worked at the American embassy in Kabul.[7]

Royal prohibition

In 1973, King Zahir Shah outlawed opium poppy and cannabis production, this time followed by genuine commitment to eradication, backed by $47 million in funding from the United States government.[8] That summer Afghan troops aggressively tackled production, destroying farms and arresting or killing cannabis farmers. Zahir Shah was deposed by his cousin Mohammed Daoud Khan that fall, who ended the monarchy and established himself as President, but the momentum of the hashish trade had been interrupted, and Western smugglers re-routed to Pakistani sources, so the 1973 harvest was minimal, as were harvests for several years following.[8]

Cannabis culture

One consumption custom in Afghanistan is eating melon along with hashish, which is said to increase the high and decrease any negative side effects.[9]

See also

References

- ^ "Afghanistan now world's top cannabis source: U.N. | Reuters".

- ^ "History of Cannabis in Afghanistan".

- ^ Nick Jones (30 July 2013). Spliffs. Pavilion Books. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-1-909396-32-6.

- ^ Robert P. Stephens (2007). Germans on Drugs: The Complications of Modernization in Hamburg. University of Michigan Press. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-0-472-06973-6.

- ^ Gilles Dorronsoro (2005). Revolution Unending: Afghanistan, 1979 to the Present. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 134–. ISBN 978-1-85065-683-8.

- ^ Shahzad Bashir; Robert D. Crews (28 May 2012). Under the Drones: Modern Lives in the Afghanistan-Pakistan Borderlands. Harvard University Press. pp. 238–. ISBN 978-0-674-06476-8.

- ^ Robert Greenfield (17 June 2009). A Day in the Life: One Family, the Beautiful People, and the End of the Sixties. Da Capo Press. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-0-7867-4800-6.

- ^ a b Martin Booth (30 September 2011). Cannabis: A History. Transworld. pp. 325–. ISBN 978-1-4090-8489-1.

- ^ Struan Stevenson (6 September 2012). Stalin's Legacy: The Soviet War on Nature. Birlinn, Limited. pp. 156–. ISBN 978-0-85790-236-8.

Further reading

- "Afghanistan Cannabis survey 2010" (PDF). UN Office on Drugs and Crime. July 2011.