Chaldean Syrian Church

| Chaldean Syrian Church Archdiocese of India of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East | |

|---|---|

| ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ ܕܐܬܘܖ̈ܝܐ കൽദായ സുറിയാനി സഭ | |

The Mar Thoma Sliva or Saint Thomas Cross, the symbol of the Church | |

| Classification | Eastern Christianity |

| Orientation | Syriac Christianity |

| Theology | East Syriac theology |

| Catholicos- Patriarch | Mar Awa III |

| Metropolitan of India | Mar Awgin Kuriakose |

| Region | India, diaspora |

| Language | Syriac, Malayalam |

| Liturgy | East Syriac Rite |

| Headquarters | Marth Mariam Cathedral Thrissur, Kerala, India |

| Founder | Saint Thomas the Apostle |

| Origin | Apostolic Era |

| Branched from | Church of the East in India |

| Members | 15,000[1] |

| Official website | Official website |

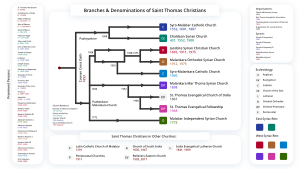

The Chaldean Syrian Church of India (Classical Syriac: ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ ܕܐܬܘܖ̈ܝܐ; Malayalam: കൽദായ സുറിയാനി സഭ / Kaldaya Suriyani Sabha) is an Eastern Christian denomination, based in Thrissur, in India. It is organized as a metropolitan province of the Assyrian Church of the East, and represents traditional Christian communities of the East Syriac Rite (hence the name) along the Malabar Coast of India.[2] It is headed by Mar Awgin Kuriakose.[3][4]

The Church uses the East Syriac Rite, and employs the Divine Liturgy of Saints Addai and Mari.[5] Its members constitute a traditional community among Saint Thomas Christians (also known as Nasrani), who trace their origins to the evangelistic activity of Thomas the Apostle in the 1st century. They are based mostly in the state of Kerala, numbering some 15,000 members in the region.[6]

The Chaldean Syrian Church is a modern-day continuation of the historical ecclesiastical province of India, that was active in continuity until the 16th century, as part of the ancient Church of the East.[7] After the long period of internal schisms and struggles, that lasted from the end of the 16th to the beginning of the 20th century, the Church was consolidated during the tenure of Mar Abimalek Timotheus (d. 1945), who is revered as a saint by the Church of the East.[8]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

Christianity in India traditionally traces its origin to Thomas the Apostle, who is believed to have evangelized in India in the 1st century. Honoring that tradition, Christians in India became known as Saint Thomas Christians. By the 3rd century, relations between Christian communities in India and neighbouring Persian Empire were well established, thus enabling Patriarchs of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, as heads of the ancient Chaldean Syrian Church of the East, to establish their jurisdiction over India. Since the East Syriac Rite was the principal liturgical rite of the Church of the East, that rite was also used by the Christian communities of India, located mostly along the Malabar Coast. In the 7th century India was designated as its own ecclesiastical province, headed by metropolitan bishops. Throughout the entire medieval period, Metropolitans of India belonged to the ecclesiastical hierarchy of the Church of the East.[9]

In 1490–1491, Patriarch Shemon IV responded to the request of Christians from India, and appointed two bishops, Mar Yohannan and Mar Awgin, dispatching them to India. These bishops, were followed by Mar Yahballaha, Mar Dinkha and Mar Yaqobin 1503–1504. They were later followed by Metropolitan Abraham, who died in 1597. By that time, Christians of the Malabar Coast were facing new challenges, caused by the establishment of Portuguese presence in India.[10][11]

Period of internal schisms and struggles

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Christianity in India |

|---|

|

The arrival of Portuguese in India, and gradual establishment of their presence along the Malabar Coast, was consequently followed by the missionary activity of the Catholic Church. Portuguese authorities used intimidation to force local Christians into becoming Eastern Catholics, though under the jurisdiction of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Goa. The Archbishops of Goa, backed by the Portuguese and the Jesuites, claimed full jurisdiction over the local Christians of the Malabar Coast. In the process, local liturgical rite was Latinized, holy books were burned under the suspicion of Nestorianism, and connection with the Church of the East in Mesopotamia was denounced at the Synod of Diamper (1599).[12][13]

Coercive actions of the Portuguese padroado system ultimately caused resistance, and in 1653 a traditionalist faction of the local Christian community decided to follow Archdeacon Mar Thoma I in a rebellion, which became known as the Coonan Cross Oath.[14][15] As a response to these events, Rome sent Carmelites from the "Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples" to the Malabar Coast. They first arrived in 1655, and began to deal directly with the Archdeacon Mar Thoma I. Although they were unable to sway the Archdeacon, Carmelites gained the support of other local leaders, including Palliveettil Chandy, Alexandar Kadavil and the Vicar of Muttam, the three councilors of Mar Thoma i.[16]

As a result of this, between 1661 and 1662, out of the 116 churches, the Carmelites reclaimed eighty-four churches, leaving Mar Thoma I with thirty-two churches. The eighty-four churches and their congregations were the body from which the later Syro-Malabar Church and the Chaldean Syrian Church have descended, while the other thirty-two churches and their congregations represented the nucleus of the Puthenkoor, which was eventually turned into the Malankara Syrian Jacobite Church, after the introduction of the West Syriac Rite. That process was initiated in 1665, when Mar Gregorios Abdal Jaleel, a bishop sent by the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch, arrived in India. The dissident group under the leadership of Mar Thoma I welcomed him, apparently mistaking him for a bishop of East Syriac Rite sent by the Church of the East.[17][18]

Though most of the Saint Thomas Christians gradually relented in their strong opposition to the Catholic influence, the arrival of the Mar Gregorios marked the new step towards permanent schism. Those who accepted new liturgical practices (West Syriac Rite) and theology of the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch became known as the "New Party" (Puthenkuttukar, also known as the Jacobites), while the remaining pro-Catholic fraction became known as "Old Party" (Pazhayakuttukar), later forming the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church.[19]

A minority within the Christian community tried to preserve the traditional use of the East Syriac Rite and re-establish ties with patriarchs of the Church of the East, who occasionally sent emissaries to India. At the very beginning of the 18th century (c. 1708), bishop Mar Gabriel (d. c. 1733) arrived to India, sent by the sitting patriarch. He succeeded in reviving the traditionalist community, but was faced with rivalry both from West Syriac (Jacobite) and pro-Catholic party.[20][21][22][23]

Revival of the East Syriac rites

[edit]The Chaldean Syrian Church's current Metropolitan, Mar Aprem Mooken, has argued that the church represents a continuation of the ancient Church of the East hierarchy in India.[7] In 1862, an attempt was made to reestablish direct ties between the community in India and the Patriarch Shimun XVIII, who consecrated an Indian born Mar Abdisho Thondanat (d. 1900) as Metropolitan of India, but his task proved to be very difficult and challenging.[24]

In order to place Christians of the East Syriac Rite in India under his authority, Chaldean Catholic Patriarch Joseph Audo sent a request to Pope Pius IX, asking for confirmation of his jurisdiction. Without waiting for a reply, he dispatched Mar Elias Mellus, Bishop of 'Aqra, to India in July 1874. Mar Mellus had substantial success convincing local Christian communities in Thrissur District, and also some churches in Kottayam District, to recognize him as their bishop. Although the churches were called by the name Syro-Malabar (also known as Chaldean Syrians at that time), the actual situation was that from Irinjalakuda to northwards and south of Bharathapuzha River, and in some churches in Meenachil taluk, the Syro-Malabarians (also known as Chaldean Syrians at that time) were half Catholic and half Nestorian, with an East Syriac liturgy. Nevertheless, by 1877, 24,000 followers had joined his group, based in Our Lady of Dolours Church (now Marth Mariam Cathedral) in the parish of Thrissur. In response, the Pope dispatched Latin Catholic leaders to remove Mar Mellus from the country and sent him back to Mesopotamia in 1882.[25]

After 1882, the majority of Mellus' followers returned to the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, but some 8,000 Christians maintained their demand for restoration of traditional ecclesiastical order. In order to answer those requests, Mar Abdisho Thondanat revived his activity, fulfilling the aspirations of local Christians of the East Syriac Rite for the full reestablishment of traditional ecclesiastical structure. Until his death in 1900, he partially succeeded in organizing the local church, that was named the Chaldean Syrian Church.[24]

After his death, local Christians appealed to Mar Shimun XIX, Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East in Qochanis who was forthcoming, and in December 1907 consecrated Mar Abimalek Timotheus as metropolitan bishop for India. He reached his diocese in February 1908, and took over the administration.[26]

Mar Abimalek Thomotheus organized ecclesiastical order and revived East Syriac rites and teachings in the local Thrissur church. These reforms caused some followers to break away and rejoin the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church, but through the reforms, the original East-Syriac oriented Church of India was revived, as it was prior to the Synod of Diamper in 1599.[27]

Modern schism and reconciliation

[edit]

In June 1952, Patriarch Shimun XXI appointed Thoma Darmo as new Metropolitan of India, based at Trichur. During his tenure, several churches were built, preparation of new clergy was organized, and the Mar Narsai Press was established. In January 1964, a dispute broke out, and Thoma Darmo was suspended from the metropolitan office by the Patriarch.[28][29]

Emerging dispute had several causes, including issues related to hereditary succession and proposed reform of church calendar. Thoma Darmo did not submit to the suspension, and the community became divided, splitting in two fractions, with one following the Metropolitan, and other remaining loyal to the Patriarch. In 1968, Thoma Darmo left for Iraq, to become head of the newly formed Ancient Church of the East. He appointed Aprem Mooken as new Metropolitan of India, for the fraction that joined the Ancient Church of the East. In the same time, the other part of community, that remained within the Assyrian Church of the East, were led by their own administrators and hierarchs, appointed by Patriarch Shimun XXI. First of them was Mar Dinkha Khanania, at that time Bishop of Iran, who was appointed Patriarchal delegate for India, in 1967.[30]

In October 1971, Patriarch Shimun XXI appointed Mar Timotheus II (d. 2001) as new Metropolitan for India.[31] During the following years, several attempts were made to heal the schism. In 1995, under new Patriarch Dinkha IV of the Assyrian Church of the East, an agreement with Metropolitan Aprem Mooken was reached, thus initiating the process of reconciliation. On that occasion, the validity of ordinations performed by Thoma Darmo after the suspension of 1964 was recognized, and in 1997 the suspension itself was annulled by the Holy Synod of the Assyrian Church of the East.[32]

The Chaldean Syrian Church in India now constitutes one of the four Archbishoprics of the Assyrian Church of the East. Its followers number around 45,000.[27] The present Metropolitan, Mar Aprem Mooken (ordained in 1968), is headquartered in Thrissur City. His seat is the Marth Mariam Valiyapalli 10°31′6″N 76°13′2″E / 10.51833°N 76.21722°E. The Chaldean Syrian Higher Secondary School is also affiliated with the church.

References

[edit]- ^ "Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East — World Council of Churches". Oikoumene.org. January 1948. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ "CHURCH OF THE EAST - INDIA". www.churchoftheeastindia.org. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ Bureau, The Hindu (8 January 2023). "Mar Awgin Kuriakose ordained as Metropolitan of the Chaldean Syrian Church of the East". The Hindu. Retrieved 5 March 2023 – via www.thehindu.com.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "CHURCH OF THE EAST - INDIA". www.churchoftheeastindia.org. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ Brown 1956, p. 281.

- ^ Vadakkekara 2007, p. 101-103.

- ^ a b Mooken 2003, p. 49–51, 65, 70.

- ^ Mooken 1975.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 51-58.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 20, 347, 398, 406-407.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 106-111.

- ^ Brown 1956, p. 32.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 115.

- ^ Brown 1956, p. 100.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 115-116.

- ^ Brown 1956, p. 103.

- ^ Brown 1956, p. 111-112.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 116.

- ^ Neill 2004, p. 327-328.

- ^ Brown 1956, p. 115-117.

- ^ Mooken 1977, p. 50-51.

- ^ Mooken 1983, p. 25-26.

- ^ Neill 2002, p. 62-65.

- ^ a b Mooken 1987.

- ^ Vadakkekara 2007, p. 102.

- ^ Mooken 1975, p. 11-26.

- ^ a b Vadakkekara 2007, p. 103.

- ^ Mooken 1974, p. 57, 64-65.

- ^ Mooken 2003, p. 169.

- ^ Mooken 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Mooken 2003, p. 180.

- ^ Mooken 2004, p. 90-92.

Sources

[edit]- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon. ISBN 9781134430192.

- Brown, Leslie W. (1956). The Indian Christians of St Thomas: An Account of the Ancient Syrian Church of Malabar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Frykenberg, Robert E. (2008). Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198263777.

- Mingana, Alphonse (1926). "The Early Spread of Christianity in India" (PDF). Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 10 (2): 435–514. doi:10.7227/BJRL.10.2.7.

- Mooken, Aprem (1974). Mar Thoma Darmo: A Biography. Trichur: Mar Narsai Press.

- Mooken, Aprem (1975). Mar Abimalek Timotheus: A Biography. Trichur: Mar Narsai Press.

- Mooken, Aprem (1977). The Chaldean Syrian Church in India. Trichur: Mar Narsai Press.

- Mooken, Aprem (1983). The Chaldean Syrian Church of the East. Delhi: National Council of Churches in India.

- Mooken, Aprem (1983x). Indian Christian: Who is Who. Bombay: Bombay Parish.

- Mooken, Aprem (1987). Mar Abdisho Thondanat: A Biography. Trichur: Mar Narsai Press.

- Mooken, Aprem (2003). The History of the Assyrian Church of the East in the Twentieth Century. Kottayam: St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute.

- Mooken, Aprem (2004). Patriarch Mar Dinkha IV: The Man and His Message. Trichur: Mar Narsai Press. ISBN 9788190220507.

- Moraes, George M. (1964). A History of Christianity in India: From Early Times to St. Francis Xavier: A. D. 52-1542. Bombay: Manaktalas.

- Mundadan, Mathias (1967). The Arrival of the Portuguese in India and the Thomas Christians Under Mar Jacob, 1498-1552. Bangalore: Dharmaram College.

- Mundadan, Mathias (1970). Sixteenth century traditions of St. Thomas Christians. Bangalore: Dharmaram College.

- Mundadan, Mathias (1984). Indian Christians: Search for Identity and Struggle for Autonomy. Bangalore: Dharmaram College.

- Neill, Stephen (1966) [1984]. Colonialism and Christian Missions. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Neill, Stephen (2004) [1984]. A History of Christianity in India: The Beginnings to AD 1707. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521548854.

- Neill, Stephen (2002) [1985]. A History of Christianity in India: 1707-1858. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521893329.

- Vadakkekara, Benedict (2007). Origin of Christianity in India: A Historiographical Critique. Delhi: Media House. ISBN 9788174952585.

- Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Louvain: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042908765.

- Wilmshurst, David (2011). The martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East. London: East & West Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781907318047.