Duke Snider

| Duke Snider | |

|---|---|

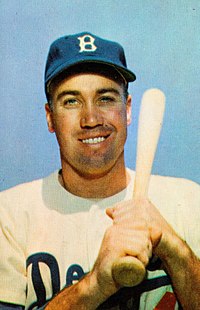

Snider in 1953 | |

| Center fielder | |

| Born: September 19, 1926 Los Angeles, California | |

| Died: February 27, 2011 (aged 84) Escondido, California | |

Batted: Left Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| April 17, 1947, for the Brooklyn Dodgers | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| October 3, 1964, for the San Francisco Giants | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .295 |

| Home runs | 407 |

| Runs batted in | 1,333 |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1980 |

| Vote | 86.49% (eleventh ballot) |

Edwin Donald "Duke" Snider (September 19, 1926 – February 27, 2011), nicknamed "The Silver Fox" and "The Duke of Flatbush", was an American professional baseball player. Usually assigned to center field, he spent most of his Major League Baseball (MLB) career playing for the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers (1947–62), later playing one season each for the New York Mets (1963) and San Francisco Giants (1964).

He was named to the National League (NL) All-Star roster eight-times and was the NL Most Valuable Player (MVP) runner-up in 1955. In his 16 out of 18 seasons with the Dodgers, he helped lead the Dodgers to six World Series, helping them win two championships in 1955 and 1959.

Snider was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1980.

Early life

Born in Los Angeles, Snider was nicknamed "Duke" by his father at age five.[1] Growing up in Southern California, Snider was a gifted all-around athlete, playing basketball, football, and baseball at Compton High School, class of 1944. He was a strong-armed quarterback, who reportedly could throw the football 70 yards.

Minor leagues

Spotted by one of Branch Rickey's scouts in the early 1940s, he was signed to a baseball contract out of high school in 1943.[1] He played briefly for the Montreal Royals of the International League in 1944 (batting twice) and for the Newport News Dodgers in the Piedmont League in the same year. After serving in the U.S. Navy in 1945 and part of 1946, he came back to play for the Fort Worth Cats that year, and also for St. Paul in 1947.

Major leagues

Snider earned a tryout with the Brooklyn Dodgers during their spring training in 1947. He got to bat in the opening game on April 17 and hit a single. He played in 39 more games that season and became a friend of Jackie Robinson before he was sent to the St. Paul team in early July. Snider returned to the Dodgers at the end of the season in time for the World Series against the New York Yankees. Snider (after spring training with the Dodgers) started the 1948 season with Montreal, and after hitting well in that league with a .327 batting average, he was called up to Brooklyn in August and played in 53 games. In 1949, Snider became a regular major leaguer hitting 23 home runs with 92 runs batted in, helping the Dodgers into the World Series. Snider also saw his average climb from .244 to .292. A more mature Snider became the "trigger man" in a power-laden lineup which boasted players Joe Black, Roy Campanella, Billy Cox, Carl Erskine, Carl Furillo, Gil Hodges, Clem Labine, Pee Wee Reese, Jackie Robinson, and Preacher Roe. Often compared with two other New York center fielders, fellow Baseball Hall of Famers, Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays, he was the reigning "Duke" of Flatbush.

In 1950, he hit .321. But when his average slipped to .277 in 1951, off 44 points from his previous mark, Snider caught the brunt of the sports‑page blame when the Dodgers squandered a 13‑game August lead and finished second to the Giants after Bobby Thomson's "Shot Heard 'Round the World". Snider recalls "I went to Walter O’Malley and told him I couldn’t take the pressure," Duke says. "I told him I’d just as soon be traded. I told him I figured I could do the Dodgers no good." Of course the trade did not happen.[2]

Usually batting third in the line-up, Snider established some impressive offensive numbers: he hit 40 or more home runs in five consecutive seasons (1953–57), and between 1953–1956 averaged 42 home runs, 124 RBI, 123 runs, and a .320 batting average. He led the National league (NL) in runs scored, home runs, and RBI in separate seasons, and appeared in six post-seasons with the Dodgers (1949, 1952–53, 1955–56, 1959), facing the New York Yankees in the first five and the Chicago White Sox in the last. The Dodgers won the World Series in 1955 and in 1959.

Snider's career numbers declined when the team moved to Los Angeles in 1958. Coupled with an aching knee and a 440-foot right field fence at the cavernous Coliseum, Snider hit only 15 home runs in 1958. However, he had one last hurrah in 1959 as he helped the Dodgers win their first World Series in Los Angeles. Duke rebounded that year to hit .308 with 23 home runs and 88 RBI in 370 at bats while sharing fielding duties in right and center fields with Don Demeter and rookie Ron Fairly. Injuries and age would eventually play a role in reducing Snider to part-time status by 1961.

In 1962 when the Dodgers led the NL for most of the season (only to find themselves tied with the hated Giants at the season's end), it was Snider and third-base coach Leo Durocher who reportedly pleaded with manager Walter Alston to bring in future Hall of Fame pitcher (and Cy Young Award winner that year) Don Drysdale in the ninth inning of the third and deciding play-off game. Instead, Alston brought in Stan Williams to relieve a tiring Eddie Roebuck. A 4-2 lead turned into a 6-4 loss as the Giants rallied to win the pennant. Snider subsequently was sold to the New York Mets. It is said that Drysdale, his roommate, broke down and cried when he got the news of Snider's departure.

When Snider joined the Mets, he discovered that his familiar number 4 was being worn by Charlie Neal, who refused to give it up. Snider wore number 11 during the first half of the season, then switched back to 4 after Neal was traded. He proved to be a sentimental favorite among former Dodger fans who now rooted for the Mets. But after one season, Snider asked to be traded to a contending team.

Snider was sold to the San Francisco Giants on Opening Day in 1964. Knowing that he had no chance of wearing number 4, which had been worn by Mel Ott and retired by the Giants, Snider took number 28. He retired at the end of that season.

He finished his major league career with a lifetime .295 batting average, 2,116 hits, 407 home runs, and 1,333 RBI.

1955 MVP balloting controversy

Snider finished second to teammate Roy Campanella in the 1955 Most Valuable Player (MVP) balloting conducted by the Baseball Writers' Association of America. He trailed Campanella by just five points, 226-221, with each man receiving eight first-place votes. A widely believed story, summarized in an article by columnist Tracy Ringolsby,[3] holds that a hospitalized writer from Philadelphia had turned in a ballot with Campanella listed as his first-place and fifth-place vote. It was assumed that the writer had meant to write Snider's name into one of those slots. Unable to get a clarification from the ill writer, the BBWAA considered disallowing the ballot but decided to accept it, counting the first-place vote for Campanella and counting the fifth-place vote as though it were left blank. Had the ballot been disallowed, the vote would have been won by Snider 221-212. Had Snider gotten that now-blank fifth-place vote, the final vote would have favored Snider 227-226.

Sportswriter Joe Posnanski, however, has suggested that this story is not entirely true.[4] Posnanski writes that there was a writer who did leave Snider off his ballot and write in Campanella's name twice, but it was in first and sixth positions, not first and fifth. Had Snider received the sixth place vote, the final tally would have created a tie, not a win for Snider. Additionally, the position was not discarded—everyone lower on the ballot was moved up a spot and the writer, and pitcher Jack Meyer was inserted at the bottom with a 10th place vote.

Snider did win the Sporting News National League Player of the Year Award for 1955, and the Sid Mercer Award, emblematic of his selection by the New York branch of the BBWAA as the National League's best player of 1955.[5]

Player statistics

| 1955 | Games | PA | AB | Runs | Hits | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BB | SO | OBP | SLG | BA | Fld% |

| Campanella Snider |

123 148 |

522 653 |

446 538 |

81 126 |

142 166 |

20 34 |

1 6 |

32 42 |

107 136 |

2 9 |

56 104 |

41 87 |

.395 .418 |

.583 .628 |

.318 .309 |

.992 .989 |

Later life

Following his retirement from baseball, Snider became a popular and respected TV/radio analyst and play-by-play announcer for the San Diego Padres from 1969 to 1971 and for the Montreal Expos from 1973 to 1986. He was characterized by a mellow, low-key style.

Snider occasionally took acting roles, sometimes appearing in television or films as himself or as a professional baseball player. He played himself in "Hero Father" (1956) in the Robert Young television series "Father Knows Best" and made one guest appearance on the Chuck Connors television series "The Rifleman", playing Wallace in "The Retired Gun" (1959). Other appearances include an uncredited part as a Los Angeles Dodgers center fielder in "The Geisha Boy" (1958), the Cranker in "The Trouble with Girls" (1969), and a Steamer Fan in "Pastime" (1990). As recently as 2007, he was featured in "Brooklyn Dodgers: The Ghosts of Flatbush."[6]

In 1995 Snider pleaded guilty to federal tax fraud charges. According to the charges, he had failed to report income from sports card shows and memorabilia sales.[7][8]

Besides his selection to the Hall of Fame in 1980, in 1999 Snider was ranked 84 on The Sporting News's list of "100 Greatest Players",[9] and was a nominee for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.

Snider married Beverly Null in 1947; they had four children.

Snider died on February 27, 2011, at age 84 of an undisclosed illness at the Valle Vista Convalescent Hospital in Escondido, California.[10] He was the last living Brooklyn Dodger who was on the field for the final out of the 1955 World Series.

MLB highlights

Some of Snider's MLB achievements:

- NL All-Star (1950–56, 1963)

- NL MVP runner-up (1955)

- NL home run leader (1956)

- NL RBI leader (1955)

- NL leader in fielding average as center fielder (1951, 1952, 1955)

- World Series champion team (1955, 1959)

- Los Angeles Dodgers: career leader in home runs (389), RBI (1,271), strikeouts (1,123), and extra-base hits (814)

- Los Angeles Dodgers: single-season record holder for most intentional walks (26 in 1956)

- Only player to hit four home runs (or more) in two different World Series (1952, 1955)

- One of two players ( besides Gil Hodges) with over 1,000 RBI during the 1950s.

Books

- Snider, Duke; Gilbert, Bill (1988). The Duke Of Flatbush. Citadel. ISBN 978-0-8065-2363-7.

- Winehouse, Irwin (1964). The Duke Snider Story. Julian Messner, Inc.

See also

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs batted in leaders

- List of members of the Baseball Hall of Fame

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2009) |

- ^ a b Jackson, Tony. Hall of Famer Duke Snider, 84, dies. ESPN.com. 2011-02-11.

- ^ Stump, Al. "Duke Snider's Story". Sport Magazine Article. SPORT magazine. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ^ Fox Sports. "Ringolsby: Don't forget the Duke". FOX Sports.

- ^ http://joeposnanski.si.com/2011/03/02/1955-mvp-a-detective-story/

- ^ The Duke of Flatbush by Duke Snider and Bill Gilbert

- ^ "The Rifleman – The Retired Gun, Episode 17, Season 1".

- ^ Lupica, Mike (1995). "The Duke muffs an easy one". The Sporting News.

- ^ Sexton, Joe (July 21, 1995). "Tax Fraud: Two Baseball Legends Say It's So". The New York Times.

- ^ "100 Greatest Baseball Players by The Sporting News : A Legendary List by Baseball Almanac".

- ^ Goldstein, Richard; Weber, Bruce (February 27, 2011). "Duke Snider, a Prince of New York's Golden Age of Baseball, Dies at 84". The New York Times.

External links

- Duke Snider at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors)

- Snider's page @ Baseball Library.com

- Snider's page @ Baseball Almanac.com

- 1926 births

- 2011 deaths

- American military personnel of World War II

- Baseball players from California

- Brooklyn Dodgers players

- Compton High School alumni

- Fort Worth Cats players

- Los Angeles Dodgers announcers

- Los Angeles Dodgers players

- Los Angeles Dodgers scouts

- Major League Baseball announcers

- Major League Baseball center fielders

- Major League Baseball players with retired numbers

- Minor league baseball managers

- Montreal Expos broadcasters

- Montreal Expos coaches

- Montreal Royals players

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- National League All-Stars

- National League home run champions

- National League RBI champions

- New York Mets players

- Newport News Dodgers players

- Sportspeople from Escondido, California

- San Diego Padres broadcasters

- San Francisco Giants players

- Sportspeople from Los Angeles

- St. Paul Saints (AA) players

- American sportsmen