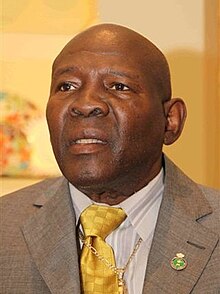

Emile Griffith

Emile Griffith | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Emile Alphonse Griffith February 3, 1938 |

| Died | July 23, 2013 (aged 75) Hempstead, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Statistics | |

| Weight(s) | Welterweight Middleweight |

| Stance | Orthodox |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 112 |

| Wins | 85 |

| Wins by KO | 23 |

| Losses | 24 |

| Draws | 2 |

| No contests | 1 |

Emile Alphonse Griffith (February 3, 1938 – July 23, 2013) was a professional boxer from the U.S. Virgin Islands who became a World Champion in the welterweight,[1] junior middleweight[2] and middleweight[3] classes. His best known contest was a 1962 title match with Benny Paret. At the weigh in, Paret infuriated Griffith, a bisexual man, by touching his buttocks and making homophobic remarks. Griffith won the bout by knockout; Paret never recovered consciousness and died in the hospital 10 days later.[4]

Career

Amateur

As a teen he was working at a hat factory on a steamy day when his boss, the factory owner, agreed to Griffith's request to work shirtless. When the owner, a former amateur boxer, noticed his frame he took Griffith to trainer Gil Clancy's gym.[5]

Griffith won the 1958 New York Golden Gloves 147 lb Open Championship. Griffith defeated Osvaldo Marcano of the Police Athletic Leagues Lynch Center in the finals to win the Championship. In 1957 Griffith advanced to the finals of the 147 lb Sub-Novice division and was defeated by Charles Wormley of the Salem Crescent Athletic Club. Griffith trained at the West 28th Street Parks Department Gym in New York City.[citation needed]

Professional

Griffith turned professional in 1958 and fought frequently in New York City. He captured the Welterweight title from Cuban Benny "The Kid" Paret by knocking him out in the 13th round on April 1, 1961. Six months later Griffith lost the title to Paret in a narrow split decision. Griffith regained the title from Paret on March 24, 1962 in the controversial bout after which Paret died, see below.

Griffith waged a classic three-fight series with Luis Rodríguez, losing the first and winning the other two. He defeated middleweight contender Holly Mims but was knocked out in one round by Rubin "Hurricane" Carter. Three years later, on April 25, 1966, he faced middleweight champion Dick Tiger and won a 15-round unanimous decision and the middleweight title. He also lost, regained and then lost the middleweight crown in three classic fights with Nino Benvenuti.

But many boxing fans believed he was never quite the same fighter after Paret's death. From the Paret bout to his retirement in 1977, Griffith fought 80 bouts but only scored twelve knockouts. He later admitted to being gentler with his opponents and relying on his superior boxing skills, because he was terrified of killing someone else in the ring. Like so many other fighters, Griffith fought well past his prime. He won only nine of his last twenty three fights.

Other boxers whom he fought in his career included world champions American Denny Moyer, Cuban Luis Rodríguez, Argentine Carlos Monzón, Nigerian Dick Tiger, Cuban José Nápoles, and in his last title try, German Eckhard Dagge. After 18 years as a professional boxer, Griffith retired with a record of 85 wins (25 by knockout), 24 losses and 2 draws.

Benny Paret

Griffith and Paret's third fight, which was nationally televised by ABC, occurred on March 24, 1962 at Madison Square Garden. Griffith had been incensed by an anti-gay slur directed at him by Paret during the weigh-in. He had worked in a women's hat factory, and later designed hats.[6] Paret touched Griffith's buttocks and called his opponent a maricón, Spanish slang for "faggot";[5]

Griffith had to be restrained from attacking him on the spot. The media at the time either ignored the slur or used euphemisms such as "anti-man". Griffith's girlfriend asked him about the incident saying "I didn't know about you being that way". In the sixth round Paret came close to stopping Griffith with a multi punch combination but Griffith was saved by the bell.[7] After the sixth round Griffith's trainer, Gil Clancy, later said he told him, "when you go inside I want you to keep punching until Paret holds you or the referee breaks you! But you keep punching until he does that!".[5]

In round 12 Griffith trapped Paret in a corner. Stunned after taking hard blows to the head, Paret stopped punching back and slumped to the side against the ropes although his upper body was through them and partly out of the ring. Griffith held his opponent's shoulder keeping him in position while using his free hand to hit Paret, who was no longer trying to protect himself by head movement or an arm guard. Griffith repeatedly landed right uppercuts on Paret's head. Many watching were shocked, and there were calls from ringside for the referee to halt the bout; Norman Mailer said it was the hardest he had ever seen one man hit by another. Paret then lolled back and was hit with a combination.[citation needed]

At this point Ruby Goldstein stepped in, thereby awarding Griffith a win by technical knockout. Immediately after the referee intervened, Paret, who had remained on his feet throughout, slowly slid to the floor. He was carried from the ring on a stretcher and died ten days later in hospital without regaining consciousness. Goldstein had a reputation as a tender-minded referee who stopped bouts at an early stage; admirers said he may have been suffering after-effects from a heart attack. He never refereed again. Paret's manager was also criticized for not retiring his boxer with a timely throwing in of the towel during the beating.[citation needed]

Griffith told a television interviewer "I'm very proud to be the welterweight champion again. I hope Paret is feeling very good." When the seriousness of the situation become known, Griffith went to the hospital where Paret was being treated and unsuccessfully attempted for several hours to gain entry to Paret's room. Following that he ran through the streets while being insulted by passers-by. He would later receive hate mail from Paret supporters who were convinced Griffith intentionally killed Paret.[5]

New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller created a seven-man commission to investigate the incident and the sport.[5] ABC, which televised the fatal bout, ended its boxing broadcasts and other U.S. networks followed; the sport would not return to free television until the 1970s[citation needed]. Griffith reportedly felt guilt over Paret's death and suffered nightmares about Paret for 40 years.[5]

The fight, and the widespread publicity and criticism of boxing which accompanied it, became the basis of the 2005 documentary Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story. In the last scene of Ring of Fire, Griffith was introduced to Paret's son. The son embraced the elderly fighter and told him he was forgiven. However, Paret's widow Lucy (died 2004) refused to meet him.[citation needed]

Trainer

Griffith trained other boxers, including Wilfred Benítez and Juan Laporte of Puerto Rico. Both won world championships. Griffith, Monzon, Benvenuti, Rodriguez, Tiger, Nápoles and Benítez are members of the International Boxing Hall of Fame. From 1979-80, he was in Denmark serving as the coach of the Danish Olympic boxing team.[citation needed]

Personal life

In 1971, two months after they met, Griffith married Mercedes "Sadie" Donastorg, who was then a member of the dance troupe "Prince Rupert and the Slave Girls". Griffith adopted Donastorg's daughter.[5] After retiring from boxing, Griffith worked as a corrections officer at the Secaucus, New Jersey Juvenile Detention Facility.[citation needed]

In 1992, Griffith was viciously beaten and almost killed on a New York City street after leaving a gay bar near the Port Authority Bus Terminal. He was in the hospital for four months after the assault. It was not clear if the violence was motivated by homophobia.[8]

Griffith was quoted in Sports Illustrated as saying "I like men and women both. But I don't like that word: homosexual, gay or faggot. I don't know what I am. I love men and women the same, but if you ask me which is better ... I like women." [5]

Death

Griffith died July 23, 2013, at a care facility in Hempstead, New York. In his final years, he required full-time care and suffered from dementia pugilistica. His adopted son, Luis Rodrigo Griffith, was his primary caregiver.[9]

Media representations

- In January 2005, filmmakers Dan Klores and Ron Berger premiered their documentary Ring Of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story at the Sundance Film Festival in Utah. It was subsequently broadcast on television on USA Network.

- Griffith's December 20, 1963 bout with Rubin Carter (which Griffith lost) is depicted in the opening scene of the 1999 motion picture The Hurricane. Griffith is portrayed by former boxer Terry Claybon, while actor Denzel Washington stars as Carter.

- In May 2012 it was announced that trumpeter Terence Blanchard and playwright Michael Cristofer were working on an opera titled Champion (opera) based on Griffith's story, which premiered at Opera Theatre of St. Louis on June 15, 2013. The opera was directed by James Robinson and starred Denyce Graves, Aubrey Allicock, Arthur Woodley, and Robert Orth.

- Irish director Lenny Abrahamson is working on a biopic focusing on Griffith's rivalry with Paret to be released in 2017.[10]

- A stage play based on Griffith's story, Brown Girl in the Ring, premiered on September 26, 2016 in Chicago. Commissioned and produced by Court Theatre, it was written by Michael Cristofer, directed by Charlie Newell, choreographed by Tommy Rapley, and starred Kamal Angelo Bolden, Allen Gilmore, Thomas J. Cox, Jacqueline Williams, Melanie Brezill, Gabriel Ruiz, Sheldon Brown, Sean Michael Sullivan. John Culbert designed sets, Jacqueline Firkins designed costumes, Keith Parham designed lights, and Andre Pluess designed sound and composed original music.

Professional boxing record

Honors

Named The Ring Fighter of the Year for 1964.

Inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in its initial year (1990) and the World Boxing Hall of Fame.

A park has been named in Griffith's honor in his native US Virgin Islands.

See also

- List of lineal boxing world champions

- List of welterweight boxing champions

- List of light middleweight boxing champions

- List of middleweight boxing champions

- List of WBC world champions

- List of WBA world champions

- List of undisputed boxing champions

- List of boxing triple champions

References

- ^ "The Lineal Welterweight Champs". Cyber Boxing Zone.

- ^ "The Lineal Junior Middleweight Champions". Cyber Boxing Zone.

- ^ "The Lineal Middleweight Champions". Cyber Boxing Zone.

- ^ "The night boxer Emile Griffith answered gay taunts with a deadly cortege of punches", theguardian.com; accessed January 30, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The Shadow Boxer", sportsillustrated.cnn.com, April 18, 2005.

- ^ I've Got a Secret episode (April 12, 1961) in which Irene and Lorraine Berlin displayed hats designed by Griffith, youtube.com; accessed January 30, 2016.

- ^ The Great Rivalries, CBSSports.com; accessed January 30, 2016.

- ^ Klores, Dan (2012-03-31). "Emile Griffith, Benny Paret and the Fatal Fight". The New York Times.

- ^ "Former boxing champion Emile Griffith dies at 75". Fox News. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ Jarlath Regan (7 March 2016). "Lenny Abrahamson". An Irishman Abroad (Podcast) (129 ed.). SoundCloud. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^ Emile Griffith's Professional Boxing Record. BoxRec.com. Retrieved on 2011-09-29.

Further reading

- Lance Pugmire, "Emile Griffith dies at 75; champion boxer struggled with his sexuality" "LA Times", July 23, 2013

- Ron Ross, ""Nine...Ten...and Out! The Two Worlds of Emile Griffith" 2008

- Donald McRae, "The Night Boxer Emile Griffith Answered Gay Taunts with a Deadly Cortege of Punches," The Guardian, September 10, 2015.

External links

- Boxing record for Emile Griffith from BoxRec (registration required)

- Emile Griffith at IMDb

- Ring Memorabilia

- 'Ring of Fire' Connects With True Story of A Fatal Blow Washington Post article April 20, 2005

- 1938 births

- 2013 deaths

- Bisexual men

- Bisexual sportspeople

- Deaths from dementia

- International Boxing Hall of Fame inductees

- LGBT boxers

- LGBT sportspeople from the United States

- Middleweight boxers

- People from Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands

- United States Virgin Islands boxers

- Welterweight boxers

- World boxing champions

- LGBT African Americans

- African-American boxers

- American male boxers