Ewe language

| Ewe | |

|---|---|

| Èʋegbe | |

| Native to | Ghana, Togo |

| Region | Southern Ghana east of the Volta River, southern Togo |

| Ethnicity | Ewe people |

Native speakers | (3.6 million cited 1991–2003)[1] |

| Latin (Ewe alphabet) Ewe Braille | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ee |

| ISO 639-2 | ewe |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:ewe – Ewewci – Wacikef – Kpesi |

| Glottolog | ewee1241 Ewekpes1238 Kpessiwaci1239 Waci Gbe |

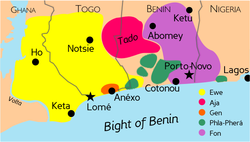

Ewe (Èʋe or Èʋegbe Template:IPA-ee)[2] is a Niger–Congo language spoken in southeastern Ghana and southern Togo by over three million people.[3] Ewe is part of a cluster of related languages commonly called Gbe; the other major Gbe language is Fon of Benin. Like many African languages, Ewe is tonal.

The German Africanist Diedrich Hermann Westermann published many dictionaries and grammars of Ewe and several other Gbe languages. Other linguists who have worked on Ewe and closely related languages include Gilbert Ansre (tone, syntax), Herbert Stahlke (morphology, tone), Nick Clements (tone, syntax), Roberto Pazzi (anthropology, lexicography), Felix K. Ameka (semantics, cognitive linguistics), Alan Stewart Duthie (semantics, phonetics), Hounkpati B. Capo (phonology, phonetics), Enoch Aboh (syntax), and Chris Collins (syntax).

History

Oral history tells of a migration of the Gbe people from Ketu in present-day Benin. It is believed that the Ewes settled first at Notsie in Togo and then moved to southeastern Ghana due to the cruelty of Togbe Agorkoli. The Ewe went through several mass exoduses beginning in the 11th century and placing current Ewe peoples in Togo, Ghana, and Benin from 15th to 17th century. The most famous of these is their migration from Notsie under the reign of King Agorkoli I. In the oral stories passed down through storytelling traditions, King Agorkoli was very cruel, as such the Ewe devised a plan to escape. Every night, the women would throw water on the walls of the kingdom which was made of mud, glass, rock, and thorns. Eventually the wall softened and they were able to cut a hole through a section of it and escape during the night. The men soon followed and walked backwards so that their footsteps would seem to lead into the kingdom.

Dialects

Some of the commonly named Ewe ('Vhe') dialects are Aŋlɔ, Tɔŋu (Tɔŋgu), Avenor, Agave people, Evedome, Awlan, Gbín, Pekí, Kpándo, Vhlin, Hó, Avɛ́no, Vo, Kpelen, Vɛ́, Danyi, Agu, Fodome, Wancé, Wací, Adángbe (Capo).

Ethnologue 16 considers Waci and Kpesi (Kpessi) to be distinct enough to be considered separate languages. They form a dialect continuum with Ewe and Gen (Mina), which share a mutual intelligibility level of 85%;[4] the Ewe varieties Gbin, Ho, Kpelen, Kpesi, and Vhlin might be considered a third cluster of Western Gbe dialects between Ewe and Gen, though Kpesi is as close or closer to the Waci and Vo dialects which remain in Ewe in that scenario. Waci intervenes geographically between Ewe proper and Gen; Kpesi forms a Gbe island in the Kabye area. Ewe is itself a dialect cluster of Gbe. Gbe languages include Gen, Aja, and Xwla and are spoken in an area that spans the southern part of Ghana into Togo, Benin, and Western Nigeria. All Gbe languages share a small degree of intelligibility with one another. Some coastal and southern dialects of Ewe include: Aŋlɔ, Tɔŋú Avenor, Dzodze, and Watsyi. Some inland dialects indigenously characterized as Ewedomegbe include: Ho, Kpedze, Hohoe, Peki, Kpando, Fódome, Danyi, and Kpele. Though there are many classifications, distinct variations exist between towns that are just miles away from one another.

Sounds

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Labial-velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | k͡p | ||||

| voiced | m ~ b | d | n ~ ɖ | ɲ ~ j | ŋ ~ ɡ | ɡ͡b | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡s | |||||||

| voiced | d͡z | ||||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | ɸ | f | s | x | ||||

| voiced | β | v | z | ɣ ~ w | ʁ/ɦ | ||||

| Approximant | l ~ l̃ | ||||||||

H is a voiced fricative which has been described as uvular, [ʁ], pharyngeal, [ʕ], or glottal [ɦ].

The nasal consonants [m, n, ɲ, ŋ] are not distinctive, as they only appear before nasal vowels. Ewe is therefore sometimes said to have no nasal consonants. However, it is more economical to argue that nasal /m, n, ɲ, ŋ/ are the underlying form, and are denasalized before oral vowels. (See vowels below.)

[ɣ] occurs before unrounded (non-back) vowels and [w] before rounded (back) vowels.

Ewe is one of the few languages known to contrast [f] vs. [ɸ] and [v] vs. [β]. The f and v are stronger than in most languages, [f͈] and [v͈], with the upper lip noticeably raised, and thus more distinctive from the rather weak [ɸ] and [β].[5]

/l/ may occur in consonant clusters. It becomes [ɾ] (or [ɾ̃]) after coronals.

Vowels

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i, ĩ | u, ũ |

| Close-mid | e, ẽ | o, õ |

| Open-mid | ɛ, ɛ̃ | ɔ, ɔ̃ |

| Open | a, ã | |

The tilde (~) marks nasal vowels, though the Peki dialect lacks /õ/. Many varieties of Ewe lack one or another of the front mid vowels, and some varieties in Ghana have the additional vowels /ə/ and /ə̃/.

Ewe does not have a nasal–oral contrast in consonants. It does, however, have a syllabic nasal, which varies as [m n ŋ], depending on the following consonant, and which carries tone. Some authors treat this as a vowel, with the odd result that Ewe would have more nasal than oral vowels, and one of these vowels has no set place of articulation. If it is taken to be a consonant, then there would be the odd result of a single nasal consonant which could not appear before vowels. If nasal consonants are taken to underlie [b ɖ ɡ], however, then there is no such odd restriction; the only difference from other consonants being that only nasal stops may be syllabic, a common pattern cross-linguistically.

Tones

Ewe is a tonal language. In a tonal language, pitch differences are used to distinguish one word from another. For example, in Ewe the following three words differ only in their tones:

- tó 'mountain' (High tone)

- tǒ 'mortar' (Rising tone)

- tò 'buffalo' (Low tone)

Phonetically, there are three tone registers, High, Mid, and Low, and three rising and falling contour tones. However, in most Ewe dialects only two registers are distinctive, High and Mid. These are depressed in nouns after voiced obstruents: High becomes Mid (or Rising), and Mid becomes Low. Mid is also realized as Low at the end of a phrase or utterance, as in the example 'buffalo' above.

Pragmatics

Ewe has phrases of overt politeness, such as meɖekuku (meaning "please") and akpe (meaning "thank you").[6]

Writing system

The African Reference Alphabet is used when Ewe is represented orthographically, so the written version is a bit like a combination of the Latin alphabet and the International Phonetic Alphabet.

| A a | B b | D d | Ɖ ɖ | Dz dz | E e | Ɛ ɛ | F f | Ƒ ƒ | G g | Gb gb | Ɣ ɣ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /a/ | /b/ | /d/ | /ɖ/ | /d͡z/ | /e/, /ə/ | /ɛ/ | /f/ | /ɸ/ | /ɡ/ | /ɡ͡b/ | /ɣ/ |

| H h | I i | K k | Kp kp | L l | M m | N n | Ny ny | Ŋ ŋ | O o | Ɔ ɔ | P p |

| /h/ | /i/ | /k/ | /k͡p/ | /l/ | /m/ | /n/ | /ɲ/ | /ŋ/ | /o/ | /ɔ/ | /p/ |

| R r | S s | T t | Ts ts | U u | V v | Ʋ ʋ | W w | X x | Y y | Z z | |

| /l/ | /s/ | /t/ | /t͡s/ | /u/ | /v/ | /β/ | /w/ | /x/ | /j/ | /z/ |

An n is placed after vowels to mark nasalization. Tone is generally unmarked, except in some common cases which require disambiguation, e.g. the first person plural pronoun mí 'we' is marked high to distinguish it from the second person plural mi 'you', and the second person singular pronoun wò 'you' is marked low to distinguish it from the third person plural pronoun wó 'they/them'

- ekpɔ wò [ɛ́k͡pɔ̀ wɔ̀] — 'he saw you'

- ekpɔ wo [ɛ́k͡pɔ̀ wɔ́] — 'he saw them'

Grammar

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

Ewe is a subject–verb–object language.[7] The possessive precedes the head noun.[8] Adjectives, numerals, demonstratives and relative clauses follow the head noun. Ewe also has postpositions rather than prepositions.[9]

Ewe is well known as a language having logophoric pronouns. Such pronouns are used to refer to the source of a reported statement or thought in indirect discourse, and can disambiguate sentences that are ambiguous in most other languages. The following examples illustrate:

- Kofi be e-dzo 'Kofi said he left' (he ≠ Kofi)

- Kofi be yè-dzo 'Kofi said he left' (he = Kofi)

In the second sentence, yè is the logophoric pronoun.

Ewe also has a rich system of serial verb constructions.

Status

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

Ewe is a national language in Togo and Ghana.

References

- ^ Ewe at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

Waci at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

Kpesi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required) - ^ [1], p. 243

- ^ Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/

- ^ N'buéké Adovi Goeh-Akué, 2009. Les états-nations face à l'intégration régionale en Afrique de l'ouest

- ^ Venda also has this distinction, but in that case [ɸ] and [β] are slightly rounded, rather than [f] and [v] being raised. (Hardcastle & Laver, The handbook of phonetic sciences, 1999:595)

- ^ Translations of "please" and "thank you" from Omniglot.com

Simon Ager (2015). "Useful Ewe phrases". Retrieved 27 June 2015. - ^ Ameka, Felix K. (1991). Ewe: Its Grammatical Constructions and Illocutionary Devices. Australian National University: Sydney.

- ^ Westermann, Diedrich. (1930). A study of the Ewe language. London: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Warburton, Irene and Ikpotufe, Prosper and Glover, Roland. (1968). Ewe Basic Course. Indiana University-African Studies Program: Bloomington.

Bibliography

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2010) |

- Ansre, Gilbert (1961) The Tonal Structure of Ewe. MA Thesis, Kennedy School of Missions of Hartford Seminary Foundation.

- Ameka, Felix Kofi (2001) 'Ewe'. In Garry and Rubino (eds.), Fact About the World's Languages: An Encyclopedia of the World's Major Languages, Past and Present, 207-213. New York/Dublin: The H.W. Wilson Company.

- Clements, George N. (1975) 'The logophoric pronoun in Ewe: Its role in discourse', Journal of West African Languages 10(2): 141-177

- Collins, Chris. (1993) Topics in Ewe Syntax. Doctoral Dissertation, MIT.

- Capo, Hounkpati B.C. (1991) A Comparative Phonology of Gbe, Publications in African Languages and Linguistics, 14. Berlin/New York: Foris Publications & Garome, Bénin: Labo Gbe (Int).

- Pasch, Helma (1995) Kurzgrammatik des Ewe Köln: Köppe.

- Westermann, Diedrich Hermann (1930) A Study of the Ewe Language London: Oxford University Press.

External links

- Basic Ewe for foreign students Institut für Afrikanistik der Universität zu Köln

- http://www.uni-koeln.de/phil-fak/afrikanistik/sprachen/ewe/ Ewe being taught at University of Cologne (Institute for African Studies Cologne)

- Ewe Basic Course by Irene Warburton, Prosper Kpotufe, Roland Glover, and Catherine Felten (textbook in Portable Digital Format and audio files in MP3 format) at Indiana University Bloomington's Center for Language Technology and Instructional Enrichment (CELTIE).

- Articles on Ewe (Journal of West African Languages)

- The Ewe language at Verba Africana

- Ewe alphabet and pronunciation page at Omniglot

- Free virtual keyboard for Ewe language at GhanaKeyboards.Com

- [2] Recordings of Ewe being spoken.

- My First Gbe Dictionary Online Gbe(Ewe)-English Glossary

- PanAfriL10n page

- Ewe IPA

- Ewe online grammar; in French. Apparently the text of Grammaire ev̳e: aide-mémoire des règles d'orthographe de l'ev̳e by Kofi J. Adzomada, 1980.