Ferdinand VII

| Ferdinand VII | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait of Ferdinand VII in his robes of state by Goya, 1815 | |||||

| King of Spain (more) | |||||

| 1st reign | 19 March 1808 – 6 May 1808 | ||||

| Predecessor | Charles IV | ||||

| Successor | Joseph I | ||||

| 2nd reign | 11 December 1813 – 29 September 1833 | ||||

| Predecessor | Joseph I | ||||

| Successor | Isabella II | ||||

| Born | 14 October 1784 San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Spain | ||||

| Died | 29 September 1833 (aged 48) Madrid, Spain | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouses | |||||

| Issue see detail... | Isabella II of Spain Infanta Luisa Fernanda, Duchess of Montpensier | ||||

| |||||

| House | Bourbon | ||||

| Father | Charles IV of Spain | ||||

| Mother | Maria Luisa of Parma | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

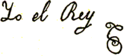

| Signature |  | ||||

Ferdinand VII (Template:Lang-es; 14 October 1784 – 29 September 1833) was twice King of Spain: in 1808 and again from 1813 to his death. He was known to his supporters as "the Desired" (el Deseado) and to his detractors as the "Felon King" (el Rey Felón). After being overthrown by Napoleon in 1808 he linked his monarchy to counter-revolution and reactionary policies that produced a deep rift in Spain between his forces on the right and liberals on the left. He reestablished the absolutist monarchy and rejected the liberal constitution of 1812. He suppressed the liberal press 1814-33 and jailed many of its editors and writers. Under his rule, Spain lost nearly all of its American possessions, and the country entered into civil war on his death.

His reputation among historians is very low. Historian Stanley Payne says:

He proved in many ways the basest king in Spanish history. Cowardly, selfish, grasping, suspicious, and vengeful, [he] seemed almost incapable of any perception of the commonwealth. He thought only in terms of his power and security and was unmoved by the enormous sacrifices of Spanish people to retain their independence and preserve his throne.[1]

Early life

Ferdinand was ostensibly the eldest surviving child of Charles IV of Spain and Maria Luisa of Parma. Ferdinand was born in the palace of El Escorial near Madrid. The Queen's confessor Fray Juan Almaraz wrote in his last will that she admitted in articulo mortis that "none, none of her sons and daughters, none was of the legitimate marriage".[2] In his youth Ferdinand occupied the position of an heir apparent who was excluded from all share in government by his parents and their favourite advisor and Prime Minister, Manuel Godoy. National discontent with the government produced a rebellion in 1805. In October 1807, Ferdinand was arrested for his complicity in the El Escorial Conspiracy in which the rebels aimed at securing foreign support from the French Emperor Napoleon. When the conspiracy was discovered, Ferdinand submitted to his parents.

Abdication and restoration

Following a popular riot at Aranjuez Charles IV abdicated in March 1808. Ferdinand ascended the throne and turned to Napoleon for support. He abdicated on 6 May 1808. Napoleon kept Ferdinand under guard in France for six years at the Chateau of Valençay.[3]

While the upper echelons of the Spanish government accepted his abdication and Napoleon's choice of his brother Joseph Bonaparte as king of Spain, the Spanish people did not. Uprisings broke out throughout the country, marking the beginning of the Peninsular War. Provincial juntas were established to control regions in opposition to the new French king. After the Battle of Bailén proved that the Spanish could resist the French, the Council of Castile reversed itself and declared null and void the abdications of Bayonne on 11 August 1808. On 24 August, Ferdinand VII was proclaimed king of Spain again, and negotiations between the Council and the provincial juntas for the establishment of a Supreme Central Junta were completed. Subsequently, on 14 January 1809, the British government acknowledged Ferdinand VII as king of Spain.[4]

Five years later after experiencing serious setbacks on many fronts, Napoleon agreed to acknowledge Ferdinand VII as king of Spain on 11 December 1813 and signed the Treaty of Valençay, so that the king could return to Spain. The Spanish people, blaming the policies of the Francophiles (afrancesados) for causing the Napoleonic occupation and the Peninsular War by allying Spain too closely to France, at first welcomed Fernando. Ferdinand soon found that in the intervening years a new world had been born of foreign invasion and domestic revolution. In his name Spain fought for its independence and in his name as well juntas had governed Spanish America. Spain was no longer the absolute monarchy he had relinquished six years earlier. Instead he was now asked to rule under the liberal Constitution of 1812. Before being allowed to enter Spanish soil, Ferdinand had to guarantee the liberals that he would govern on the basis of the Constitution, but, only gave lukewarm indications he would do so.[5]

On 24 March the French handed him over to the Spanish Army in Girona, and thus began his procession towards Madrid.[6] During this process and in the following months, he was encouraged by conservatives and the Church hierarchy to reject the Constitution. On 4 May he ordered its abolition and on 10 May had the liberal leaders responsible for the Constitution arrested. Ferdinand justified his actions by claiming that the Constitution had been made by a Cortes illegally assembled in his absence, without his consent and without the traditional form. (It had met as a unicameral body, instead of in three chambers representing the three estates: the clergy, the nobility and the cities.) Ferdinand initially promised to convene a traditional Cortes, but never did so, thereby reasserting the Bourbon doctrine that sovereign authority resided in his person only.

Meanwhile, the wars of independence had broken out in the Americas, and although many of the republican rebels were divided and royalist sentiment was strong in many areas, the Manila galleons and the Spanish treasure fleets - tax revenues from the Spanish Empire - were interrupted. Spain was all but bankrupt.

Ferdinand's restored autocracy was guided by a small camarilla of his favorites, although his government seemed unstable. Whimsical and ferocious by turns, he changed his ministers every few months. "The king," wrote Friedrich von Gentz in 1814, "himself enters the houses of his prime ministers, arrests them, and hands them over to their cruel enemies;" and again, on 14 January 1815, "the king has so debased himself that he has become no more than the leading police agent and prison warden of his country."

The king did recognize the efforts of foreign powers on his behalf. As the head of the Spanish Order of the Golden Fleece, Ferdinand made the Duke of Wellington, head of the British forces on the peninsula, the first Protestant member of the order.

Revolt

In 1820 a revolt broke out in favor of the Constitution of 1812 which began with a mutiny of the troops under Col. Rafael del Riego and the king was quickly made prisoner. Ferdinand had restored the Jesuits upon his return; now the Society had become identified with repression and absolutism among the liberals, who attacked them: twenty-five Jesuits were slain in Madrid in 1822. For the rest of the 19th century, expulsions and reinstatements of the Jesuits would continue to be the hallmarks of liberal and authoritarian political regimes, respectively.

At the beginning of 1823, as a result of the Congress of Verona, the French invaded Spain "invoking the God of St Louis, for the sake of preserving the throne of Spain to a descendant of Henry IV, and of reconciling that fine kingdom with Europe." When in May the revolutionary party carried Ferdinand to Cádiz, he continued to make promises of amendment until he was free.

When Ferdinand was freed after the Battle of Trocadero and the fall of Cádiz, reprisals followed. The Duke of Artois made known his protest against Ferdinand's actions by refusing the Spanish decorations Ferdinand offered him for his military services.

During his last years Ferdinand's political appointments became more stable. The last ten years of reign (sometimes referred to as the Ominous Decade) saw the restoration of absolutism, the re-establishment of traditional university programs and the suppression of any opposition, both of the Liberal Party and of the reactionary revolt (known as "War of the Agraviados") which broke out in 1827 in Catalonia and other regions.

Death and succession crisis

As Ferdinand lay dying his new wife, Maria Christina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies had him set aside the Salic Law, which would make his brother Don Carlos heir to the throne instead of any female. Ferdinand was thus succeeded by his infant daughter Isabella II. Carlos revolted and said he was the legitimate king. Needing support, Maria Christina (as Regent for her daughter Isabella) turned to the liberals. She issued a decree of amnesty on 23 October 1833. Liberals who had been in exile returned and dominated Spanish politics for decades, and the Carlist Wars resulted.[7][8]

Marriages

Ferdinand VII was married four times. In 1802 he married his first cousin Princess Maria Antonietta of the Two Sicilies (1784–1806), daughter of Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies and Marie Caroline of Austria. There were no children, because her two pregnancies (in 1804 and 1805) ended in miscarriages.

In 1816, Ferdinand married his niece Maria Isabel of Portugal (1797–1818), daughter of his older sister Carlota Joaquina and John VI of Portugal. She bore him two daughters, the first of whom lived only five months and the second of whom was stilborn.

In 1819, Ferdinand married Princess Maria Josepha Amalia of Saxony (1803–1829), daughter of Maximilian, Prince of Saxony and Caroline of Bourbon-Parma. No children were born from this marriage.

Lastly, in 1829, Ferdinand married another niece, Maria Christina of Bourbon-Two Sicilies (1806–1878), daughter of his younger sister Maria Isabella of Spain and Francis I of the Two Sicilies. She bore him two daughters.

Issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Burial | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| By Maria Isabel of Portugal (1797–1818) | ||||

| Infanta María Luisa Isabel | 21 August 1817 Madrid |

9 January 1818 Madrid |

El Escorial | Princess of Asturias. |

| Infanta María Luisa Isabel | Madrid |

El Escorial | Stillborn; Maria Isabel died as a result of her birth. | |

| By Maria Christina of the Two Sicilies (1806–1878) | ||||

| Infanta María Isabel Luisa | 10 October 1830 Madrid |

10 April 1904 Paris |

El Escorial | Princess of Asturias 1830–1833, Queen of Spain 1833–1868. Married Francis, Duke of Cádiz, had issue. |

| Infanta Luisa Fernanda | 30 January 1832 Madrid |

2 February 1897 Seville |

El Escorial | Married Antoine, Duke of Montpensier, had issue. |

Ancestry

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- ^ Payne, p 2:428

- ^ Zavala, José María (2011). Bastardos y Borbones. Barcelona: Plaza & Janés Editores. ISBN 978-84-0138-992-4. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ Carr, pp 79-85

- ^ Carr, pp 85-90

- ^ Carr, pp 105-19

- ^ Artola, Miguel. La España de Fernando VII. Madrid, Espasa, 1999, 405. ISBN 84-239-9742-1

- ^ A.W. Ward and G.P. Gooch (1970). The Cambridge History of British Foreign Policy 1783-1919 (reprint ed.). CUP. pp. 186–87.

- ^ John Van der Kiste (2011). Divided Kingdom: The Spanish Monarchy from Isabel to Juan Carlos. History Press Limited. pp. 6–9.

Further reading

- Carr, Raymond. Spain, 1808-1975 (1982)

- Clarke, Henry Butler. Modern Spain, 1815-98 (1906) pp 1–92; old but full of factual detail online

- Fehrenbach, Charles Wentz. "Moderados and Exaltados: The Liberal Opposition to Ferdinand VII, 1814-1823." Hispanic American Historical Review (1970): 52-69. in JSTOR

- Payne, Stanley G. History of Spain and Portugal: v. 2 (1973) pp 415–36

- Woodward, Margaret L. "The Spanish Army and the Loss of America, 1810-1824." Hispanic American Historical Review (1968): 586-607. in JSTOR

External links

- Historiaantiqua. Fernando VII at Historia Antiqua Template:Es icon

- Use dmy dates from March 2011

- Nobility from Madrid

- Spanish monarchs

- Roman Catholic monarchs

- Princes of Asturias

- House of Bourbon (Spain)

- Knights of Santiago

- Knights of the Garter

- Knights of the Golden Fleece

- 1784 births

- 1833 deaths

- Burials in the Pantheon of Kings at El Escorial

- 19th-century Roman Catholics

- Grand Masters of the Order of the Golden Fleece

- Grand Masters of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

- Grand Masters of the Royal and Military Order of San Hermenegild

- 19th-century monarchs in Europe