Gaslamp Quarter, San Diego

Gaslamp Quarter Historic District | |

San Diego Historic Landmark No. 127 | |

| |

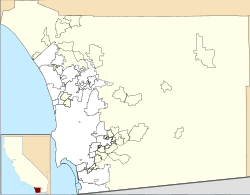

| Location | Bounded by RR tracks, Broadway, 4th, and 6th Aves., San Diego, California |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 32°42′42″N 117°9′33″W / 32.71167°N 117.15917°W |

| Area | 38 acres (15 ha) |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian, Art Deco |

| NRHP reference No. | 80000841[1] |

| SDHL No. | 127 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 23, 1980 |

| Designated SDHL | June 2, 1978[2] |

The Gaslamp Quarter is a historic neighborhood in downtown San Diego, California. It extends from Broadway to Harbor Drive and from 4th to 6th Avenue. The neighborhood is listed as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places as the Gaslamp Quarter Historic District. It includes over 90 historic buildings,[3] most of which were constructed in the Victorian era; many are in use as restaurants, shops, entertainment venues, and nightclubs.

The Gaslamp Quarter is known for its nightlife. It is the site of various events and festivals, including Mardi Gras in the Gaslamp, Taste of Gaslamp, and ShamROCK, a St. Patrick's Day event. Petco Park, home of the San Diego Padres, is one block away in the East Village neighborhood.

History

[edit]

In the 1860s, the area was known as New Town, in contrast to Old Town, the original Spanish colonial settlement of San Diego.[4][better source needed] Intensive development began in 1867, when Alonzo Horton bought the land in hopes of creating a new city center closer to the bay, and chose 5th Avenue as its main street.[5]

After a period of urban decay, the neighborhood underwent urban renewal in the 1980s and 1990s.[6]

It was rebranded the "Gaslamp Quarter" during the redevelopment and preservation efforts that occurred during the 1980s, though the streets were generally lit by arc lights, not gaslamps.[citation needed]

Timeline

[edit]- 1850: William Heath Davis bought 160 acres (0.65 km2) in what would eventually become the Gaslamp Quarter. Despite heavy investment from Davis, little development happened in this period.[7]

- 1867: Real estate developer Alonzo Horton arrived in San Diego and purchased 800 acres (3.2 km2) of land in New Town for $265. Major development began in the Gaslamp Quarter.[8]

- 1880s to 1916: Known as the Stingaree, the area was a working class area, home to San Diego's first Chinatown, "Soapbox Row" and many saloons, gambling halls, and bordellos.

- 1912: Stingaree was the site of a free speech fight between socialists and city politicians which led to riots and the abduction by vigilantes of Emma Goldman's husband.[9]

- 1916: the entire neighborhood of Stingaree was demolished and renamed by anti-vice campaigners.[10]

- 1950s-1970s: The decaying Gaslamp Quarter became known as a "Sailor's Entertainment" district, with a high concentration of pornographic theaters, bookshops and massage parlors.[11]

- 1970: Public interest in preserving buildings downtown started, especially in Gaslamp Quarter.

- 1976: The city adopted the Gaslamp Quarter Urban Design and Development Manual, aimed at preserving buildings in the area, and the redevelopment of Gaslamp Quarter as a national historic district.[12]

- 1982: Gaslamp Quarter became the major focus of the redevelopments in downtown by the city of San Diego.[citation needed]

- 1992: Gaslamp Quarter Archway is installed and dedicated.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Historical Landmarks Designated by the San Diego Historical Resources Board" (PDF). City of San Diego. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ "San Diego - Gaslamp Quarter Historical Markers". www.hmdb.org. Retrieved May 30, 2024.

- ^ "10 Fun Facts About San Diego's Historic Gaslamp Quarter". San Diego Tourism Authority. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ "Alonzo Horton – Gaslamp Quarter Historical Foundation". gaslampfoundation.org. Retrieved May 30, 2024.

- ^ "Gaslamp Quarter Historic District | TCLF". The Cultural Landscape Foundation. Retrieved May 30, 2024.

- ^ "William Heath Davis". Gaslamp Quarter Historical Foundation. Archived from the original on February 20, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ "San Diego Historical Society". Archived from the original on December 24, 2015. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- ^ Dotinga, Randy (March 15, 2011). "When San Diego Had Its Own Big Labor Clash". Voice of San Diego. Archived from the original on December 3, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ MacPhail, Elizabeth (Spring 1970). "Shady Ladies in the "Stingaree District": WHEN THE RED LIGHTS WENT OUT IN SAN DIEGO". The Journal of San Diego History. 20 (2). Archived from the original on October 24, 2005 – via sandiegohistory.org.

- ^ Sanford, Jay Allen (July 23, 2008). "Before It Was the Gaslamp: Downtown's Grindhouse Row (updated 8-22-09)". San Diego Reader. Archived from the original on July 8, 2009. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ^ Lia, Marie Burke (2009). "Gaslamp Quarter Planned District Design Guidelines 2009" (PDF). SanDiego.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 9, 2021.

- ^ "Gaslamp Quarter History | Downtown San Diego, California". gaslamp.org. Archived from the original on February 21, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Gaslamp Quarter, San Diego

- Entertainment districts in California

- Culture of San Diego

- Landmarks in San Diego

- Historic districts in San Diego

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in California

- National Register of Historic Places in San Diego

- Neighborhoods in San Diego

- Urban communities in San Diego