Geographical distribution of Russian speakers

This article details the geographical distribution of Russian-speakers. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the status of the Russian language often became a matter of controversy. Some Post-Soviet states adopted policies of de-Russification aimed at reversing former Russification trends.

After the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, de-Russification occurred in newly-independent Finland, Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and in the Kars Oblast (which became part of Turkey).

The newly-formed Soviet Union initially implemented a policy of Korenizatsiya, which aimed (in part) at the reversal of the tsarist Russification of the non-Russian areas of the country.[1] Korenizatsiya (meaning "nativization" or "indigenization", literally "putting down roots") was the early Soviet nationalities policy promoted mostly in the 1920s but with a continuing legacy in later years. The primary policy consisted of promoting representatives of titular nations of Soviet republics and national minorities on lower levels of the administrative subdivision of the state, into local government, management, bureaucracy and nomenklatura in the corresponding national entities.

Joseph Stalin mostly reversed the implementation of Korenizatsiya in the 1930s, not so much by changing the letter of the law but by reducing its practical effects and by introducing de facto Russification. The Soviet system heavily promoted the Russian language as the "language of inter-ethnic communication". Eventually, in 1990, Russian became legally the official all-Union language of the Soviet Union, with constituent republics having rights to declare their own official languages.[2][3]

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, about 25 million Russians (about one sixth of former Soviet Russians) found themselves outside Russia; as of 2013[update] these people constituted about 10% or more of the population of eight of the fifteen post-Soviet states other than Russia. Many[quantify] millions of ex-Soviet citizens - Russians and non-Russians - have became refugees due to various inter-ethnic conflicts[4] or to economic pressures.

Statistics

Native speakers

| Country | Speakers | Percentage | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23,484 | 0.8% | 2011 | [5] | |

| 44,058 | 0.2% | 2012 | [5] | |

| 8,446 | 0.1% | 2001 | [5] | |

| 122,449 | 1.4% | 2009 | [5] | |

| 6,672,964 | 70.2% | 2009 | [5][note 1] | |

| 112,150 | 0.3% | 2011 | [5] | |

| 1,592 | 0.04% | 2011 | [5] | |

| 20,984 | 2.5% | 2011 | [5] | |

| 31,622 | 0.3% | 2011 | [5] | |

| 383,118 | 29.6% | 2011 | [5] | |

| 77,777 | 1.5% | 2017 | [5] | |

| 45,920 | 1.2% | 2014 | [5] | |

| 2,104 | 0.14% | 2009 | [5] | |

| 3,793,800 | 21.2% | 2017 | [6] | |

| 482,200 | 8.9% | 2009 | [7] | |

| 698,757 | 33.8% | 2011 | [5] | |

| 218,383 | 7.2% | 2011 | [5] | |

| 40 | 0.003% | 2011 | [5] | |

| 264,162 | 9.7% | 2014 | [8] | |

| 7,896 | 0.2% | 2006 | [5] | |

| 16,833 | 0.3% | 2012 | [5] | |

| 21,916 | 0.1% | 2011 | [5] | |

| 18,946 | 0.09% | 2011 | [5] | |

| 3,179 | 0.04% | 2011 | [5] | |

| 1,866 | 0.03% | 2001 | [5] | |

| 40,598 | 0.5% | 2012 | [5] | |

| 14,273,670 | 29.6% | 2001 | [5] | |

| 879,434 | 0.3% | 2013 | [9] |

Native and non-native speakers

| Country | Speakers | Percentage | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,591,246 | 52.7% | 2011 | [10] | |

| 678,102 | 7.6% | 2009 | [11] | |

| 928,655 | 71.7% | 2011 | [12][note 3] | |

| 10,309,500 | 84.8% | 2009 | [13][note 4] | |

| 1,854,700 | 49.6% | 2009 | [7][note 5] | |

| 1,917,500 | 63.0% | 2011 | [14] | |

| 137,494,893 | 96.2% | 2010 | [5][note 6] | |

| 1,963,857 | 25.9% | 2010 | [15] |

Unspecified

| Country | Speakers | Percentage | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,155,960 | 15% | 2011 | [16] | |

| 700,500 | 12.8% | 2017 | [6] | |

| 650,000 | 2.1% | 2017 | [6] |

Asia

Armenia

In Armenia Russian has no official status, but it's recognized as a minority language under the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 15,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 1 million active speakers.[18] 30% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 2% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[19] Russian is spoken by 1.4% of the population according to a 2009 estimate from the World Factbook.[20]

In 2010 in a significant pullback to de-Russification, Armenia voted to re-introduce Russian-medium schools.[21]

Azerbaijan

In Azerbaijan Russian has no official status, but is a lingua franca of the country.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 250,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 2 million active speakers.[18] 26% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 5% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[19]

Research in 2005-2006 concluded that government officials did not consider Russian to be a threat to the strengthening role of the Azerbaijani language in independent Azerbaijan. Rather, Russian continued to have value given the proximity of Russia and strong economic and political ties. However, it was seen as self-evident that in order to be successful, citizens needed to be proficient in Azerbaijani.[22]

Georgia

In Georgia Russian has no official status, but it's recognized as a minority language under the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 130,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 1.7 million active speakers.[18] 27% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 1% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[19] Russian is the language of 9% of the population according to the World Factbook.[23] Ethnologue cites Russian as the country's de facto working language.[24]

Georgianization has been pursued with most official and private signs only in the Georgian language, with English being the favored foreign language. Exceptions are older signs remaining from Soviet times, which are generally bilingual Georgian and Russian. Private signs and advertising in Samtskhe-Javakheti region which has a majority Armenian population are generally in Russian only or Georgian and Russian.[citation needed] In the Borchali region which has a majority ethnic Azerbaijani population, signs and advertising are often in Russian only, in Georgian and Azerbaijani, or Georgian and Russian. De-Russification has not been pursued in areas outside Georgian government control, Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[citation needed]

Israel

Russian is also spoken in Israel by at least 1,000,000 ethnic Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union, according to the 1999 census. The Israeli press and websites regularly publish material in Russian.[citation needed]

Kazakhstan

In Kazakhstan Russian is not a state language, but according to article 7 of the Constitution of Kazakhstan its usage enjoys equal status to that of the Kazakh language in state and local administration.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 4,200,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 10 million active speakers.[18] 63% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 46% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[19] According to a 2001 estimate from the World Factbook, 95% of the population can speak Russian.[20] Large Russian-speaking communities still exist in northern Kazakhstan, and ethnic Russians comprise 25.6% of Kazakhstan's population.[25] The 2009 census reported that 10,309,500 people, or 84.8% of the population aged 15 and above, could read and write well in Russian, as well as understand the spoken language.[26]

Kyrgyzstan

In Kyrgyzstan Russian is an official language per article 5 of the Constitution of Kyrgyzstan.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 600,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 1.5 million active speakers.[18] 38% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 22% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[19]

The 2009 census states that 482,200 people speak Russian as a native language, including 419,000 ethnic Russians, and 63,200 from other ethnic groups, for a total of 8.99% of the population.[7] Additionally, 1,854,700 residents of Kyrgyzstan aged 15 and above fluently speak Russian as a second language, or 49.6% of the population in the age group.[7]

Other than Russia itself and Belarus, the Russian language has the strongest position in Kyrgyzstan of all the post-Soviet states. Russian remains co-official with Kyrgyz, which remains written in Cyrillic script. Russian remains the dominant language of business and upper levels of government. Parliament sessions are only rarely conducted in Kyrgyz and mostly take place in Russian. In 2011 President Roza Otunbaeva controversially reopened the debate about Kyrgyz getting a more dominant position in the country.[27]

Tajikistan

In Tajikistan Russian is the language of inter-ethnic communication under the Constitution of Tajikistan.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 90,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 1 million active speakers.[18] 28% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 7% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[19] The World Factbook notes that Russian is widely used in government and business.[20]

After independence Tajik was declared the sole state language and until 2009, Russian was designated the "language for interethnic communication". The 2009 law stated that all official papers and education in the country should be conducted only in the Tajik language. However, the law also stated that all minority ethnic groups in the country have the right to choose in which language they want their children to be educated.[28]

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan pursued intense de-Russification and was the first in Central Asia (in 1991) to change the local language's alphabet (in this case Turkmen) to Latin script.[citation needed] Russian lost its status as the official lingua franca in 1996.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 150,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 100,000 active speakers.[18] Russian is spoken by 12% of the population according to an undated estimate from the World Factbook.[20]

The situation in Turkmenistan differs from other countries in Central Asia: while hundreds of Turkmen students do attend school in Russia, favorable visa conditions have attracted a much larger number of Turkmens to Turkey, both as illegal workers and as students. Turkmen is closely related to Turkish. While Russian TV channels have mostly been shut down inside Turkmenistan, Turkish satellite programming is widely available. Turkish schools now fill the gap left by the closing of Russian-language schools, and over 600 Turkish companies operate in Turkmenistan.[29]

Uzbekistan

In Uzbekistan Russian has no official status, but is a lingua franca of the country.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 1,200,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 5 million active speakers.[18] Russian is spoken by 14.2% of the population according to an undated estimate from the World Factbook.[20]

After the independence of Uzbekistan in 1991, Uzbek culture underwent the three trends of de-Russification, the creation of an Uzbek national identity, and westernization. The Uzbek state has primarily promoted these trends through the educational system, which is particularly effective because nearly half the Uzbek population is of school age or younger.[30]

Since the Uzbek language became official and privileged in hiring and firing, there has been a brain drain of ethnic Russians in Uzbekistan. The displacement of the Russian-speaking population from the industrial sphere, science and education has weakened these spheres. As a result of this emigration, participation in Russian cultural centers like the State Academy Bolshoi Theatre in Uzbekistan has seriously declined.[30]

In the capital Tashkent, statues of the leaders of the Russian Revolution were taken down and replaced with local heroes like Timur, and urban street names in the Russian style were Uzbekified. In 1995, Uzbekistan ordered the Uzbek alphabet changed from a Russian-based Cyrillic script to a modified Latin alphabet, and in 1997, Uzbek became the sole language of state administration.[30]

Rest of Asia

In 2005, Russian was the most widely taught foreign language in Mongolia,[31] and was compulsory in Year 7 onward as a second foreign language in 2006.[32]

Russian is also spoken as a second language by a small number of people in Afghanistan.[33]

Australia

Australian cities Melbourne and Sydney have Russian-speaking populations, with the most Russians living in southeast Melbourne, particularly the suburbs of Carnegie and Caulfield. Two-thirds of them are actually Russian-speaking descendants of Germans, Greeks, Jews, Azerbaijanis, Armenians or Ukrainians, who either repatriated after the USSR collapsed, or are just looking for temporary employment.[citation needed]

Europe

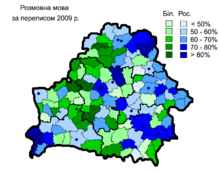

Belarus

In Belarus, Russian is co-official alongside Belarusian per the Constitution of Belarus.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 3,243,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 8 million active speakers.[18] 77% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 67% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[19]

Initially, when Belarus became independent in 1991 and the Belarusian language became the only state language, some de-russification began.[citation needed] However, after the Alexander Lukashenko became President of Belarus, a referendum held in 1995 (considered fraudulent by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe) included a question about the status of Russian language, After that Russian was made a state language along with Belarusian.

In most spheres in the country the Russian language is by far the dominant one. In fact, almost all government information and websites are in Russian only.[citation needed]

Bulgaria

Bulgaria has the largest proportion of Russian speakers among European countries that were not part of the USSR.[34] According to a 2012 Eurobarometer survey, 19% of the population understands Russian well enough to follow the news, television or radio.[34]

Estonia

In Estonia, Russian is officially considered a foreign language.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 470,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 500,000 active speakers.[18] 35% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 25% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[19] Russian is spoken by 29.6% of the population according to a 2011 estimate from the World Factbook.[20]

Ethnic Russians constitute 25.5% of the country's current population[35] and 58.6% of the native Estonian population is also able to speak Russian.[36] In all, 67.8% of Estonia's population could speak Russian.[36] Command of Russian language, however, is rapidly decreasing among younger Estonians (primarily being replaced by the command of English). For example, if 53% of ethnic Estonians between 15 and 19 claimed to speak some Russian in 2000, then among the 10- to 14-year-old group, command of Russian had fallen to 19% (which is about one-third the percentage of those who claim to have command of English in the same age group).[36]

In 2007, Amnesty International harshly criticized what it termed Estonia's "harassment" of Russian speakers.[37] In 2010, Estonian language inspectorate stepped up inspections at workplaces to ensure that state employees spoke Estonian at an acceptable level. This included inspections of teachers at Russian-medium schools.[38] Amnesty International continues to criticize Estonian policies stating "Non-Estonian speakers, mainly from the Russian-speaking minority, were denied employment due to official language requirements for various professions in the private sector and almost all professions in the public sector. Most did not have access to affordable language training that would enable them to qualify for employment."[39]

Finland

Russian is spoken by 1.4% of the population of Finland according to a 2014 estimate from the World Factbook.[20] Russian is the third most spoken native language in Finland,[40] and one of the fastest growing ones in terms of native speakers as well as learners as a foreign language.[41]

Russian language is becoming more prominent due to increase in trade with and tourism to and from the Russian Federation and other Russian-speaking countries and regions.[42] There is a steadily increasing demand for the knowledge of Russian in the workplace, also reflected in its growing presence in the Finnish education system, including higher education.[43] In Eastern Finland Russian has already begun rivaling Swedish as the second most important foreign language.[44]

Germany

Germany has the highest Russian-speaking population outside the former Soviet Union with approximately 3 million people.[45] They are split into three groups, from largest to smallest: Russian-speaking ethnic Germans (Aussiedler), ethnic Russians, and Jews.

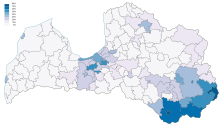

Latvia

In 1988 the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic declared Latvian the sole official language of Soviet Latvia.[46]

Despite large Russian-speaking minorities in Latvia (26.9% ethnic Russians, 2011)[47] Russian is officially considered a foreign language.[17] 55% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 26% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[19]

On March 2010 fact-sheets in Russian produced by the EU executive's offices in Latvia were withdrawn, provoking criticism from Plaid Cymru MEP and European Free Alliance group President Jill Evans who called European Commission to continue to provide information in non-official EU languages and commented that "it's disappointing to hear that the EU is bowing to pressure to exclude Russian speakers in the Baltic in this way".[48]

A constitutional referendum held in February 2012 proposed amendments to Constitution that would make Russian the second state language of Latvia was put to referendum, but 821,722 (75%) of the voters voted against compared to 273,347 (25%). There has been criticism that about 290,000 of the 557,119 (2011) ethnic Russians in Latvia are non-citizens and do not have the right to vote, however even assuming they all had voted for the amendments proposed they still would not have passed.[49]

Beginning in 2019, instruction in Russian language will be gradually discontinued in private colleges and universities, as well general instruction in public high schools,[50] except for subjects related to culture and history of the Russian minority, such as Russian language and literature classes.[51]

Lithuania

On January 25, 1989, the presidium of the Supreme Soviet of Lithuanian SSR decreed Lithuanian as “the main means of official communication” for all companies, institutions and organizations in the Lithuanian SSR with the exception of the Soviet Army. In the Constitution passed in 1992, Lithuanian was explicitly stated as the state language.[52]

In Lithuania Russian is not official, but it still retains the function of lingua franca.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 250,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 500,000 active speakers.[18] 20% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 3% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[19] In contrast to the other two Baltic states, Lithuania has a relatively small Russian-speaking minority (5.0% as of 2008).[52]

In 2011, 63% of the Lithuanian population, or 1,917,500 people,[53] had a command of the Russian language.[54]

Moldova

In Moldova, Russian is considered to be the language of inter-ethnic communication under a Soviet-era law.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 450,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 1.9 million active speakers.[18] 50% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 19% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[19] Russian is the language usually spoken by 16% of Moldovans according to a 2004 estimate from the World Factbook.[20]

Russian has a co-official status alongside Romanian in the autonomies of Gagauzia and Transnistria in Moldova.

Russia

According to the census of 2010 in Russia Russian language skills were indicated by 138 million people (99.4% population), while according to the 2002 census - 142.6 million people (99.2% population). Among the urban residents 101 million people (99.8% population) had Russian language skills, while in rural areas - 37 million people (98.7% population).[55] The number of native Russian speakers in 2010 was 118.6 millions or 85.7%, that was a little higher than the number of ethnic Russians (111 million, 80.9%).

Russian is the official language of Russia, although it shares the official status at regional level with other languages in the numerous ethnic autonomies within Russia, such as Chuvashia, Bashkortostan, Tatarstan, and Yakutia. 94% of school students in Russia receive their education primarily in Russian.[56]

In Dagestan, Chechnya and Ingushetia, De-Russification is understood not so much directly in the disappearance of Russian language and culture but rather by the exodus of Russian speaking people themselves, which intensified after the First and Second Chechen Wars, Islamization and by 2010 had reached a critical point. The displacement of the Russian-speaking population from the industrial sphere, science and education has weakened these spheres.[57]

In the Republic of Karelia, in 2007 it was announced that the Karelian language was to be used at national events,[58] however Russian is still the only official language (Karelian is one of several "national" languages) and virtually all business and education is conducted in Russian. In 2010 less than 8% of the republic's population was ethnic Karelian.

Russification is reported to be continuing in Mari El.[59]

Ukraine

In Ukraine, Russian is seen as a language of inter-ethnic communication, and a minority language, under the 1996 Constitution of Ukraine.[17] According to estimates from Demoskop Weekly, in 2004 there were 14,400,000 native speakers of Russian in the country, and 29 million active speakers.[18] 65% of the population was fluent in Russian in 2006, and 38% used it as the main language with family, friends or at work.[19]

In 1990 Russian became legally the official all-Union language of the Soviet Union, with constituent republics having rights to declare their own official languages.[2][3] Previously in 1989 the Ukrainian SSR government adopted Ukrainian as its official language, which with dissolution of the Soviet Union was affirmed as the only official state language of independent Ukraine. The educational system in Ukraine has been transformed over the first decade of independence from a system that was overwhelmingly Russian into one where over 75% of tuition is in Ukrainian. The government has also mandated a progressively increased role for Ukrainian in the media and commerce.

In a July 2012 poll by RATING 55% of the surveyed (Ukrainians older than 18 years) believed that their native language was rather Ukrainian and 40% rather Russian, 5% could not decide which language was their native one[60]). However, the transition lacked most of the controversies that surrounded the de-Russification in several of the other former Soviet Republics.[citation needed]

In some cases, the abrupt changing of the language of instruction in institutions of secondary and higher education, led to the charges of assimilation, raised mostly by the Russian-speaking population.[citation needed] In various elections the adoption of Russian as an official language was an election promise by one of the main candidates (Leonid Kuchma in 1994, Viktor Yanukovych in 2004 and Party of Regions in 2012).[61][62][63][64] After the introduction of the 2012 legislation on languages in Ukraine Russian was declared a "regional language" in several southern and eastern parts of Ukraine.[65] On 28 February 2018 the Constitutional Court of Ukraine ruled this legislation unconstitutional.[66]

Rest of Europe

In the 20th century, Russian was a mandatory language taught in the schools of the members of the old Warsaw Pact and in other countries that used to be satellites of the USSR. In particular, these countries include Poland, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Albania, former East Germany and Cuba. However, younger generations are usually not fluent in it, because Russian is no longer mandatory in the school system. According to the Eurobarometer 2005 survey,[67] though, fluency in Russian remains fairly high (20–40%) in some countries, in particular those where the people speak a Slavic language and thereby have an edge in learning Russian (namely, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Bulgaria).

Significant Russian-speaking groups also exist in Western Europe.[citation needed] These have been fed by several waves of immigrants since the beginning of the 20th century, each with its own flavor of language. The United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Belgium, Greece, Norway, and Austria have significant Russian-speaking communities.

According to the 2011 Census of Ireland, there were 21,639 people in the nation who use Russian as a home language. However, of this only 13% were Russian nationals. 20% held Irish citizenship, while 27% and 14% were holding the passports of Latvia and Lithuania respectively.[68]

There were 20,984 Russian speakers in Cyprus according to the Census of 2011, accounting for 2.5% of the population.[69] Russian is spoken by 1.6% of the Hungarian population according to a 2011 estimate from the World Factbook.[20]

The Americas

The language was first introduced in North America when Russian explorers voyaged into Alaska and claimed it for Russia during the 1700s. Although most Russian colonists left after the United States bought the land in 1867, a handful stayed and preserved the Russian language in this region to this day, although only a few elderly speakers of this unique dialect are left.[70] Sizable Russian-speaking communities also exist in North America, especially in large urban centers of the U.S. and Canada, such as New York City, Philadelphia, Boston, Los Angeles, Nashville, San Francisco, Seattle, Spokane, Toronto, Baltimore, Miami, Chicago, Denver and Cleveland. In a number of locations they issue their own newspapers, and live in ethnic enclaves (especially the generation of immigrants who started arriving in the early 1960s). Only about 25% of them are ethnic Russians, however. Before the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the overwhelming majority of Russophones in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn in New York City were Russian-speaking Jews. Afterward, the influx from the countries of the former Soviet Union changed the statistics somewhat, with ethnic Russians and Ukrainians immigrating along with some more Russian Jews and Central Asians. According to the United States Census, in 2007 Russian was the primary language spoken in the homes of over 850,000 individuals living in the United States.[71]

There is a small community of Russian Brazilians who have kept the use of the Russian language, mostly in the hinterland of the southern state of Paraná.

See also

Notes

- ^ Data note: "Data refer to mother tongue, defined as the language usually spoken in the individual's home in his or her early childhood."

- ^ Based on a 2016 population of 17,855,000 (UN Statistics Division Archived 2014-01-25 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Includes 383,118 native and 545,537 non-native speakers.

- ^ People aged 15 and above who can read and write Russian well.

- ^ Data refers to the resident population aged 15 years and over.

- ^ Data note: "Including all of persons who stated each language spoken, whether as their only language or as one of several languages. Where a person reported more than one language spoken, they have been counted in each applicable group."

- ^ Based on a 2011 population of 7,706,400 (Central Bureau of Statistics of Israel[permanent dead link])

- ^ Based on a 2016 population of 5,439,000 (UN Statistics Division Archived 2017-06-06 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Based on a 2016 population of 30,300,000 (UN Statistics Division Archived 2017-06-06 at the Wayback Machine)

References

- ^ "EMPIRE, NATIONALITIES, AND THE COLLAPSE OF THE USSR", VESTNIK, THE JOURNAL OF RUSSIAN AND ASIAN STUDIES, May 8, 2007 Archived November 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Language Policy in the Soviet Union". Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "СССР. ЗАКОН СССР ОТ 24.04.1990 О ЯЗЫКАХ НАРОДОВ СССР". Archived from the original on 2016-05-08. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

Compare:

Efron, Sonni (8 June 1993). "Case Study: Russians: Becoming Strangers in Their Homeland: Millions of Russians are now unwanted minorities in newly independent states, an explosive situation". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

Ethnic hostilities have already scorched a dozen lands on the periphery of the former Soviet Union, claiming at least 25,000 lives since 1988 and creating several million refugees. [...] One in every six Russians is now living outside the Russian Federation. These 25 million people--roughly equal to the entire population of Canada--represent 10% or more of the population in eight of the former republics. [...] Officially, 1.5 million refugees from all over the former Soviet empire have registered with the Russian government since 1989, Solntsev said. The flow is speeding up, with an average of 1,000 to 2,000 new refugees arriving each month. Officials fear Russia may have to accept 6 million refugees from the troubled former republics in the next few years.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y "Population by language, sex and urban/rural residence". UNdata. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Zubacheva, Ksenia (16 May 2017). "Why Russian is still spoken in the former Soviet republics". Russia Beyond The Headlines. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Population And Housing Census Of The Kyrgyz Republic Of 2009" (PDF). UN Stats. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Structure of population by mother tongue, in territorial aspect in 2014". Statistica.md. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Language Spoken At Home By Ability To Speak English For The Population 5 Years And Over". American FactFinder. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ^ "Population (urban, rural) by Ethnicity, Sex and Fluency in Other Language" (PDF). ArmStat. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Distribution of population by native language and freely command of languages (based on 2009 population census)". State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "PC0444: Population By Mother Tongue, Command Of Foreign Languages, Sex, Age Group And County, 31 December 2011". Stat.ee. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Results of the 2009 National population census of the Republic of Kazakhstan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 November 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "10 lentelė. Gyventojai pagal mokamas užsienio kalbas ir amžiaus grupes". Stat.gov.lt. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Национальный состав и владение языками, гражданство населения Республики Таджикистан" (PDF). Агентство по статистике при Президенте Республики Таджикистан. p. 58. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. "Selected Data from the 2011 Social Survey on Mastery of the Hebrew Language and Usage of Languages (Hebrew Only)". Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Русский язык в новых независимых государствах" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Падение статуса русского языка на постсоветском пространстве". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Русскоязычие распространено не только там, где живут русские". Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 2016-10-23. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i "Languages". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 17 February 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Armenia introduces Russian-language education", Russkiy Mir, Dec, 10, 2010 Archived May 25, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Nation-Building and Language Policy in post-Soviet Azerbaijan", Kyle L. Marquardt, PhD Student, Political Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Georgia". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-09. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Population Grows to 15.4 Million, More Births, Less Emigration Are Reasons". Kazakhstan News Bulletin - Embassy of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 20 April 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Results Of The 2009 National Population Census Of The Republic Of Kazakhstan" (PDF). Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ "Language A Sensitive Issue In Kyrgyzstan". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tajikistan Drops Russian As Official Language". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "In Post-Soviet Central Asia, Russian Takes A Backseat", Muhammad Tahir, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, September 28, 2011 Archived December 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Dollerup, Cay. "Language and Culture in Transition in Uzbekistan". In Atabaki, Touraj; O'Kane, John (eds.). Post-Soviet Central Asia. Tauris Academic Studies. pp. 144–147.

- ^ Brooke, James (February 15, 2005). "For Mongolians, E Is for English, F Is for Future". The New York Times. New York Times. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Русский язык в Монголии стал обязательным [Russian language has become compulsory in Mongolia] (in Russian). New Region. 21 September 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-10-09. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ^ Awde and Sarwan, 2003

- ^ a b "Eurobarometer 386" (PDF). European Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Diagram". Pub.stat.ee. Archived from the original on 2012-12-22. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Population census of Estonia 2000. Population by mother tongue, command of foreign languages and citizenship". Statistics Estonia. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "ESTONIA: LANGUAGE POLICE GETS MORE POWERS TO HARASS", 27 February 2007, Amnesty International Archived December 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Estonia Raises Its Pencils to Erase Russian", CLIFFORD J. LEVY, New York Times, June 7, 2010 Archived September 17, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Estonia". Amnesty International USA. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-30. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-18. Retrieved 2015-05-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Levan Tvaltvadze. "Министр культуры предлагает изучать русский алфавит в школе". Yle Uutiset. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lioubov Shalygina. "Русский язык помогает найти работу, но в паре с ним хотят видеть спецобразование". Yle Uutiset. Archived from the original on 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Муниципалитеты ходатайствуют об альтернативном русском языке в школе". Yle Uutiset. Archived from the original on 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2016-08-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ See Bernhard Brehmer: Sprechen Sie Qwelja? Formen und Folgen russisch-deutscher Zweisprachigkeit in Deutschland. In: Tanja Anstatt (ed.): Mehrsprachigkeit bei Kindern und Erwachsenen. Tübingen 2007, S. 163–185, here: 166 f., based on Migrationsbericht 2005 des Bundesamtes für Migration und Flüchtlinge. (PDF)

- ^ Decision on status of the Latvian language (Supreme Council of Latvian SSR, 06.10.1988.) Archived 2008-06-08 at the Wayback MachineTemplate:Lv icon

- ^ Population Census 2011 - Key Indicators Archived 2012-06-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Russian speakers 'excluded' from EU brochures in Latvia". EurActiv.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Latvians Reject Russian as Second Language", DAVID M. HERSZENHORN, New York Times, February 19, 2012 Archived March 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Latvian president promulgates bill banning teaching in Russian at private universities". The Baltic Course. April 7, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ "Government okays transition to Latvian as sole language at schools in 2019". Latvijas Sabiedriskais medijs. January 23, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Ethnic and Language Policy of the Republic of Lithuania: Basis and Practice, Jan Andrlík Archived 2016-04-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Gyventojai pagal išsilavinimą ir kalbų mokėjimą" (PDF). Oficialiosios statistikos portalas. p. 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Population by educational attainment and command of languages". OSP. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Демоскоп Weekly. Об итогах Всероссийской переписи населения 2010 года. Сообщение Росстата". Demoscope.ru. 2011-11-08. Archived from the original on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Об исполнении Российской Федерацией Рамочной конвенции о защите национальных меньшинств. Альтернативный доклад НПО. (in Russian). MINELRES. p. 80. Archived from the original (Doc) on 2009-03-25. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "How many Russians are left in Dagestan, Chechnya and Ingushetia?", 3 May 2010, Vestnik Kavkaza Archived 17 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "22.07.2009 - Karelian language to be used for all national events". Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Goble, Paul (December 17, 2008). "Russification Efforts in Mari El Disturb Hungarians". Estonian World Review. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ The language question, the results of recent research in 2012 Archived 2015-07-09 at the Wayback Machine, RATING (25 May 2012)

- ^ Migration, Refugee Policy, and State Building in Postcommunist Europe Archived 2017-09-17 at the Wayback Machine by Oxana Shevel, Cambridge University Press, 2011,ISBN 0521764793

- ^ Ukraine's war of the words Archived 2016-08-17 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian (5 July 2012)

- ^ FROM STABILITY TO PROSPERITY Draft Campaign Program of the Party of Regions Archived December 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Party of Regions Official Information Portal (27 August 2012)

- ^ "Яценюк считает, что если Партия регионов победит, может возникнуть «второй Майдан»", Novosti Mira (Ukraine) Archived 2012-11-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Yanukovych signs language bill into law". Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Constitutional Court declares unconstitutional language law of Kivalov-Kolesnichenko, Ukrinform (28 February 2018)

- ^ "Europeans and their Languages" (PDF). europa.eu. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-05-21.

- ^ "Ten Facts from Ireland's Census 2011". WorldIrish. 2012-03-29. Archived from the original on 2012-03-31. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

- ^ Στατιστική Υπηρεσία - Πληθυσμός και Κοινωνικές Συνθήκες - Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Ανακοινώσεις - Αποτελέσματα Απογραφής Πληθυσμού, 2011 (in Greek). Demoscope.ru. Archived from the original on 2013-05-07. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ninilchik". languagehat.com. 2009-01-01. Archived from the original on 2014-01-07. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Language Use in the United States: 2007, census.gov" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-06-14. Retrieved 2013-06-18.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- Uralic family home page

- Language Controversy in Kyrgyzstan - Institute for War and Peace Reporting, 23 November 2005

- Ukrainian language - the third official? - Ukrayinska Pravda, 28 November 2005