Georges Cuvier

Georges Cuvier | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 23, 1769 |

| Died | 13 May 1832 (aged 62) |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | establishing the fields of stratigraphy and comparative anatomy; the first thorough, published documentation of faunal succession in the fossil record; making extinction an accepted scientific phenomenon; opposition to gradualistic theories of evolution |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Natural history, paleontology, anatomy |

| Institutions | Muséum national d'histoire naturelle |

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier (French: [kyvje] (né Johann Leopold Nicolaus Friedrich Küfer); born August 23, 1769 Mömpelgard, Duchy of Wurtemberg (since 1800 Montbéliard, département du Doubs) – died May 13, 1832 Paris, known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist. Cuvier was a major figure in natural sciences research in the early 19th century, and was instrumental in establishing the fields of comparative anatomy and paleontology through his work in comparing living animals with fossils.

Cuvier's work is considered the foundation of vertebrate paleontology, and he expanded Linnaean taxonomy by grouping classes into phyla and incorporating both fossils and living species into the classification. Cuvier is also well known for establishing extinction as a fact—at the time, extinction was considered by many of Cuvier's contemporaries to be merely controversial speculation. In his Essay on the Theory of the Earth (1813) Cuvier proposed that new species were created after periodic catastrophic floods. In this way, Cuvier became the most influential proponent of catastrophism in geology in the early 19th century,[1] His study of the strata of the Paris basin with Alexandre Brongniart established the basic principles of biostratigraphy.

Among his other accomplishments, Cuvier established that elephant-like bones found in the USA actually belonged to an extinct mastodon, and that a large skeleton dug up in Paraguay was of Megatherium, a giant, prehistoric sloth. He also named (but did not discover) the aquatic reptile Mosasaurus and the pterosaur Pterodactylus, and was one of the first people to suggest the earth had been dominated by reptiles, rather than mammals, in prehistoric times. Cuvier is also remembered for strongly opposing the evolutionary theories of Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. Cuvier believed there was no evidence for the evolution of organic forms, but rather evidence for successive creations after catastrophic extinction events. His most famous work is Le Règne Animal (1817; English: The Animal Kingdom).

In 1819, he was created a peer for life in honor of his scientific contributions.[2] Thereafter he was known as Baron Cuvier. He died in Paris during an epidemic of cholera. Some of Cuvier's most influential followers were Louis Agassiz on the continent and in America, and Richard Owen in England. His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Biography

Cuvier was born in Montbéliard, France (in department of Doubs), where his Protestant ancestors had lived since the time of the Reformation.[3] His father, Jean George Cuvier, was a lieutenant in the Swiss Guards and a bourgeois of the town of Montbéliard; his mother was Anne Clémence Chatel.[4] At the time, the town which was annexed to France on 10 October 1793 belonged to the Duchy of Württemberg.[5] His mother, who was much younger than his father, tutored him diligently throughout his early years, so he easily surpassed the other children at school.[3] During his gymnasium years, he had little trouble acquiring Latin and Greek, and was always at the head of his class in mathematics, history, and geography.[6] According to Lee,[6] "The history of mankind was, from the earliest period of his life, a subject of the most indefatigable application; and long lists of sovereigns, princes, and the driest chronological facts, once arranged in his memory, were never forgotten."

Soon after entering the gymnasium, at age 10, he encountered a copy of Gesner's Historiae Animalium, the work that first sparked his interest in natural history. He then began frequent visits to the home of a relation where he could borrow volumes of Buffon's massive Histoire Naturelle. All of these he read and reread, retaining so much of the information that by the age of 12 "he was as familiar with quadrupeds and birds as a first-rate naturalist."[6] He remained at the gymnasium for four years.

Cuvier spent an additional four years at the Caroline Academy in Stuttgart, where he excelled in all of his coursework. Although he knew no German on his arrival, after only 9-months study, he managed to win the school prize for that language. Upon graduation, he had no money to await appointment to academic office. So in July 1788, he took a job at Fiquainville chateau in Normandy as tutor to the only son of the Comte d'Héricy, a Protestant noble. There, during the early 1790s, he began his comparisons of fossils with extant forms. Cuvier regularly attended meetings held at the nearby town of Valmont for the discussion of agricultural topics. There, he became acquainted with Henri Alexandre Tessier (1741–1837), a physician and well-known agronomist who had fled the Terror in Paris and assumed a false identity. After hearing Tessier speak on agricultural matters, Cuvier recognized him as the author of certain articles on agriculture in the Encyclopédie Méthodique and addressed him as M. Tessier. Tessier replied in dismay, "I am known, then, and consequently lost." — " Lost!" replied M. Cuvier; "no; you are henceforth the object of our most anxious care."[8] They soon became intimate and Tessier introduced Cuvier to his colleagues in Paris — "I have just found a pearl in the dunghill of Normandy", he wrote his friend Antoine-Augustin Parmentier.[9] As a result, Cuvier entered into correspondence with several leading naturalists of the day, and was invited to Paris. Arriving in the spring of 1795, at the age of 26, he soon became the assistant of Jean-Claude Mertrud (1728–1802), who had been appointed to the newly created chair of comparative anatomy at the Jardin des Plantes.[10]

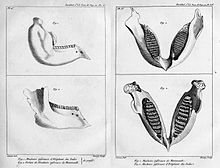

The Institut de France was founded in the same year, and he was elected a member of its Academy of Sciences. In 1796, he began to lecture at the École Centrale du Pantheon, and at the opening of the National Institute in April, he read his first paleontological paper, which was subsequently published in 1800 under the title Mémoires sur les espèces d'éléphants vivants et fossiles. In this paper, he analyzed skeletal remains of Indian and African elephants, as well as mammoth fossils, and a fossil skeleton known at that time as the 'Ohio animal'. Cuvier's analysis established, for the first time, the fact that African and Indian elephants were different species and that mammoths were not the same species as either African or Indian elephants, so must be extinct. He further stated that the 'Ohio animal' represented a distinct extinct species that was even more different from living elephants than mammoths were. Years later, in 1806, he would return to the 'Ohio animal' in another paper and give it the name "mastodon".

In his second paper in 1796, he would describe and analyze a large skeleton found in Paraguay, which he would name Megatherium. He concluded that this skeleton represented yet another extinct animal and, by comparing its skull with living species of tree-dwelling sloths, that it was a kind of ground-dwelling giant sloth. Together, these two 1796 papers were a landmark event in the history of paleontology, and in the development of comparative anatomy, as well. They also greatly enhanced Cuvier's personal reputation, and they essentially ended what had been a long-running debate about the reality of extinction.

In 1799, he succeeded Daubenton as professor of natural history in the Collège de France. In 1802, he became titular professor at the Jardin des Plantes; and in the same year he was appointed commissary of the Institute to accompany the inspectors general of public instruction. In this latter capacity, he visited the south of France, but in the early part of 1803, he was chosen Permanent Secretary of the Department of Physical Sciences of the Academy, and he consequently abandoned the earlier appointment and returned to Paris. In 1806, he became a foreign member of the Royal Society, and in 1812, a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

He then devoted himself more especially to three lines of inquiry: (i) the structure and classification of the Mollusca; (ii) the comparative anatomy and systematic arrangement of the fishes; (iii) fossil mammals and reptiles and, secondarily, the osteology of living forms belonging to the same groups.

In 1812, Cuvier made what Bernard Heuvelmans called his "Rash Dictum": he remarked that it was unlikely that any large animal remained undiscovered. The word "dinosaur" was coined in 1842.

During his lifetime, Cuvier served as an Imperial Councillor under Napoleon, President of the Council of Public Instruction and Chancellor of the University under the restored Bourbons, Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour, a Peer of France, Minister of the Interior, and President of the Council of State under Louis Philippe; he was eminent in all these capacities, and yet the dignity given by such high administrative positions was as nothing compared to his leadership in natural science.[11]

Cuvier was by birth, education, and conviction a devout Lutheran,[12] and remained Protestant throughout his life while regularly attending church services. Despite this, he regarded his personal faith as a private matter; he evidently identified himself with his confessional minority group when he supervised governmental educational programs for Protestants. He was also very active in founding the Parisian Biblical Society in 1818, where he later served as a vice president.[13] From 1822 until his death in 1832, Cuvier was Grand Master of the Protestant Faculties of Theology of the French University.[14]

Scientific ideas and their impact

Opposition to evolution

He repeatedly emphasized that his extensive experience with fossil material indicated that one fossil form does not, as a rule, gradually change into a succeeding, distinct fossil form (see below). Because of this and his understanding of animal anatomy and physiology, Cuvier strongly objected to any notion of evolution. According to the University of California Museum of Paleontology, "Cuvier did not believe in organic evolution, for any change in an organism's anatomy would have rendered it unable to survive. He studied the mummified cats and ibises that Geoffroy had brought back from Napoleon's invasion of Egypt, and showed that they were no different from their living counterparts; Cuvier used this to support his claim that life forms did not evolve over time." [15]

He also observed that Napoleon's expedition to Egypt had retrieved animals mummified thousands of years previously that seemed no different from their modern counterparts.[16] "Certainly", Cuvier wrote, "one cannot detect any greater difference between these creatures and those we see, than between the human mummies and the skeletons of present-day men."[17] Lamarck dismissed this conclusion, arguing that evolution happened much too slowly to be observed over just a few thousand years. Cuvier, however, in turn criticized how Lamarck and other naturalists conveniently introduced hundreds of thousands of years "with a stroke of a pen" to uphold their theory. Instead, he argued that one can judge what a long time would produce only by multiplying what a lesser time produces. Since a lesser time produced no organic changes, neither, probably, would a much longer time.[18]

Cuvier was critical of the evolutionary theories proposed by his contemporaries Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, which involved the gradual transmutation of one form into another. He repeatedly emphasized that his extensive experience with fossil material indicated that one fossil form does not, as a rule, gradually change into a succeeding, distinct fossil form. Instead, he said, the typical form makes an abrupt appearance in the fossil record, and persists unchanged to the time of its extinction. Cuvier attempted to explain this paleontological phenomenon (which would be readdressed more than a century later by "punctuated equilibrium") and harmonize it with the Bible, attributing the different time periods as intervals between major catastrophes, the last of which is found in Genesis.[19][20] He was skeptical of the gradual mechanisms of change that Lamarck and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire proposed. Moreover, his commitment to the Principle of the correlation of parts caused him to doubt that any mechanism could ever gradually modify any part of an animal in isolation from all the other parts (in the way Lamarck proposed), without rendering the animal unable to survive.[21] In his Éloge de M. de Lamarck (Praise for M. de Lamarck),[22][23] Cuvier noted that Lamarck's theory of evolution

- "rested on two arbitrary suppositions; the one, that it is the seminal vapor which organizes the embryo; the other, that efforts and desires may engender organs. A system established on such foundations may amuse the imagination of a poet; a metaphysician may derive from it an entirely new series of systems; but it cannot for a moment bear the examination of anyone who has dissected a hand, a viscus, or even a feather."

Cuvier's claim that new fossil forms appear abruptly in the geological record and then continue without alteration in overlying strata was used by later thinkers to support creationism.[24] The abruptness seemed consistent with special creation by God (although Cuvier's finding that different types made their paleontological debuts in different geological strata clearly did not). The lack of change was consistent with the supposed sacred immutability of "species", but, again, the idea of extinction, of which Cuvier was the great proponent, obviously was not.

Many writers have unjustly accused Cuvier of obstinately maintaining that fossil human beings could never be found. In his Essay on the Theory of the Earth, he did say that "no human bones have yet been found among fossil remains", but he made it clear exactly what he meant: "When I assert that human bones have not been hitherto found among extraneous fossils, I must be understood to speak of fossils, or petrifactions, properly so called".[25] Petrified bones, which have had time to mineralize and turn to stone, are typically far older than ordinary bones. Cuvier's point was that all human fossils that he knew of were of relatively recent age because they had not been petrified and had been found only in superficial strata.[26] But he was not dogmatic in this claim. When new evidence came to light, he included in a later edition an appendix describing a skeleton that he freely admitted was an "instance of a fossil human petrifaction".[27]

The harshness of his criticism and the strength of his reputation continued to discourage naturalists from speculating about the gradual transmutation of species, right up until Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species more than two decades after Cuvier's death.[28]

Extinction

At the time Cuvier presented his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, it was still widely believed that no species of animal had ever become extinct. Authorities such as Buffon had claimed that fossils found in Europe of animals such as the woolly rhinoceros and mammoth were remains of animals still living in the tropics (i.e. rhinoceros and elephants), which had shifted out of Europe and Asia as the earth became cooler. Cuvier's early work demonstrated conclusively that this was not the case.[29]

Catastrophism

Cuvier came to believe that most, if not all, the animal fossils he examined were remains of species that were now extinct. Near the end of his 1796 paper on living and fossil elephants, he said:

- All of these facts, consistent among themselves, and not opposed by any report, seem to me to prove the existence of a world previous to ours, destroyed by some kind of catastrophe.

This led Cuvier to become an active proponent of the geological school of thought called catastrophism which maintained that many of the geological features of the earth and the history of life could be explained by catastrophic events that had caused the extinction of many species of animals. Over the course of his career, Cuvier came to believe there had not been a single catastrophe, but several, resulting in a succession of different faunas. He wrote about these ideas many times, in particular he discussed them in great detail in the preliminary discourse (introduction) to a collection of his papers, Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes (Researches on quadruped fossil bones), on quadruped fossils published in 1812. The 'Preliminary Discourse' became very well known, and unauthorized (and in the case of English not entirely accurate) translations were made into English, German, and Italian. In 1826, Cuvier would publish a revised version under the name Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du globe (Discourse on the upheavals of the surface of the globe).[30]

After Cuvier's death, the catastrophic school of geological thought lost ground to uniformitarianism, as championed by Charles Lyell and others, which claimed that the geological features of the earth were best explained by currently observable forces, such as erosion and volcanism, acting gradually over an extended period of time. However, the increasing interest in the topic of mass extinction starting in the late 20th century has led to a resurgence of interest among historians of science and other scholars in this aspect of Cuvier's work.

Stratigraphy

Cuvier collaborated for several years with Alexandre Brongniart, an instructor at the Paris mining school, to produce a monograph on the geology of the region around Paris. They published a preliminary version in 1808 and the final version was published in 1811. In this monograph they identified characteristic fossils of different rock layers that they used to analyze the geological column, the ordered layers of sedimentary rock, of the Paris basin. They concluded that the layers had been laid down over an extended period during which there clearly had been faunal succession and that the area had been submerged under sea water at times and at other times under fresh water. Along with William Smith's work during the same period on a geological map of England, which also used characteristic fossils and the principle of faunal succession to correlate layers of sedimentary rock, the monograph helped establish the scientific discipline of stratigraphy. It was a major development in the history of paleontology and the history of geology.[31]

Age of reptiles

In 1800, Cuvier was the first to correctly identify in print, working only from a drawing, a fossil found in Bavaria as a small flying reptile,[32] which he named the Ptero-Dactyle in 1809[33] (later Latinized as Pterodactylus antiquus)--the first known member of the diverse order of pterosaurs. In 1808 Cuvier identified a fossil found in Maastricht as a giant marine lizard, which he named Mosasaurus, the first known mosasaur. Cuvier speculated that there had been a time when reptiles rather than mammals had been the dominant fauna.[34] This speculation was confirmed over the next two decades by a series of spectacular finds, mostly by English geologists and fossil collectors such as Mary Anning, William Conybeare, William Buckland, and Gideon Mantell, who found and described the first ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and dinosaurs.

Principle of the correlation of parts

In a 1798 paper on the fossil remains of an animal found in some plaster quarries near Paris Cuvier wrote:[35]

- Today comparative anatomy has reached such a point of perfection that, after inspecting a single bone, one can often determine the class, and sometimes even the genus of the animal to which it belonged, above all if that bone belonged to the head or the limbs. ... This is because the number, direction, and shape of the bones that compose each part of an animal's body are always in a necessary relation to all the other parts, in such a way that - up to a point - one can infer the whole from any one of them and vice versa.

This idea is sometimes referred to as 'Cuvier's principle of correlation of parts', and while Cuvier's description may somewhat exaggerate its power, the basic concept is central to comparative anatomy and paleontology.

Principle of the conditions of existence

For Cuvier, the principle of the correlation of parts was theoretically justified by a further principle, that of the conditions d'existence, usually translated as "conditions of existence." This was his way of understanding function in a non-evolutionary context, without invoking a divine creator.[36] In the same 1798 paper he wrote:

- if an animal's teeth are such as they must be, in order for it to nourish itself with flesh, we can be sure without further examination that the whole system of its digestive organs is appropriate for that kind of food, and that its whole skeleton and locomotive organs, and even its sense organs, are arranged in such a way as to make it skillful at pursuing and catching its prey. For these relations are the necessary conditions of existence of the animal; if things were not so, it would not be able to subsist.

This principle later influenced the positivist philosopher Auguste Comte, and the physiologist Claude Bernard.[37]

Chief scientific work

Comparative anatomy and classification

in 1798 Cuvier published his first independent work, the Tableau élémentaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux, which was an abridgment of his course of lectures at the École du Pantheon, and may be regarded as the foundation and first statement of his natural classification of the animal kingdom.

In 1800 he published the Leçons d'anatomie comparée, assisted by A. M. C. Duméril for the first two volumes and Georges Louis Duvernoy for the three later ones.

Molluscs

Cuvier's papers on the so-called Mollusca began appearing as early as 1792, but most of his memoirs on this branch were published in the Annales du museum between 1802 and 1815; they were subsequently collected as Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire et à l'anatomie des mollusques, published in one volume at Paris in 1817.

"When the French Academy was preparing its first dictionary, it defined "crab" as, "A small red fish which walks backwards." This definition was sent with a number of others to the naturalist Cuvier for his approval. The scientist wrote back, "Your definition, gentlemen, would be perfect, only for three exceptions. The crab is not a fish, it is not red and it does not walk backwards."

Source unknown, but probably Times Literary Supplement (UK).

Fish

Cuvier's researches on fish, begun in 1801, finally culminated in the publication of the Histoire naturelle des poissons, which contained descriptions of 5000 species of fishes, and was the joint production of Cuvier and Achille Valenciennes. Cuvier's work on this project extended over the years 1828–1831.

Palaeontology and osteology

In this field Cuvier published a long list of memoirs, partly relating to the bones of extinct animals, and partly detailing the results of observations on the skeletons of living animals, specially examined with a view of throwing light upon the structure and affinities of the fossil forms.

Among living forms he published papers relating to the osteology of the Rhinoceros Indicus, the tapir, Hyrax capensis, the hippopotamus, the sloths, the manatee, etc.

He produced an even larger body of work on fossils, dealing with the extinct mammals of the Eocene beds of Montmartre, the fossil species of hippopotamus, a marsupial (which he called Didelphys gypsorum), the Megalonyx, the Megatherium, the cave-hyena, the pterodactyl, the extinct species of rhinoceros, the cave bear, the mastodon, the extinct species of elephant, fossil species of manatee and seals, fossil forms of crocodilians, chelonians, fish, birds, etc. The department of palaeontology dealing with the Mammalia may be said to have been essentially created and established by Cuvier.

The results of Cuvier's principal palaeontological and geological investigations were ultimately given to the world in the form of two separate works: Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes (Paris, 1812; later editions in 1821 and 1825); and Discours sur les revolutions de la surface du globe (Paris, 1825). In this latter work he expounded a scientific theory of Catastrophism.

The Animal Kingdom

None of Cuvier's works attained a higher reputation than his Le Règne Animal, the first edition of which appeared in four octavo volumes in 1817, and the second in five volumes in 1829–1830. In this classic work Cuvier embodied the results of the whole of his previous researches on the structure of living and fossil animals. The whole of the work was his own, with the exception of the section on Insecta, in which he was assisted by his friend Latreille. It was translated into English many times, often with substantial notes and supplementary material updating the book in accordance with the expansion of knowledge.

Racial studies

Cuvier was a Protestant and a believer in monogenism who held that all men descended from the biblical Adam. However, his position was usually confused as being polygenist (some writers who have studied his racial work have dubbed his position as "quasi-polygenist"), and most of his racial studies have influenced scientific racialism. Cuvier believed there were three distinct races: the Caucasian (white), Mongolian (yellow) and the Ethiopian (black). Cuvier claimed that Adam and Eve were Caucasian, the original race of mankind. The other two races originated by survivors escaping in different directions after a major catastrophe hit the earth 5,000 years ago, with those survivors then living in complete isolation from each other.[38][39]

Cuvier assigned marks to each race according to the beauty or ugliness of their skulls and the quality of their civilizations. He placed the white race at the top with the most beautiful skull, and the black race at the bottom.[40]

Cuvier wrote regarding Caucasians:

The white race, with oval face, straight hair and nose, to which the civilised people of Europe belong and which appear to us the most beautiful of all, is also superior to others by its genius, courage and activity.[41]

Regarding Negros, he wrote:

The Negro race... is marked by black complexion, crisped of woolly hair, compressed cranium and a flat nose, The projection of the lower parts of the face, and the thick lips, evidently approximate it to the monkey tribe: the hordes of which it consists have always remained in the most complete state of barbarism.[42]

Cuvier's racial studies held the main features of polygenism which are as follows:[38]

- Fixity of species

- Strict limits on environmental influence

- Unchanging underlying type

- Anatomical and cranial measurement differences in races

- Physical and mental differences between racial worth

- Human races are all distinct

Official and public work

Apart from his own original investigations in zoology and paleontology Cuvier carried out a vast amount of work as perpetual secretary of the National Institute, and as an official connected with public education generally; and much of this work appeared ultimately in a published form. Thus, in 1808 he was placed by Napoleon upon the council of the Imperial University, and in this capacity he presided (in the years 1809, 1811 and 1813) over commissions charged to examine the state of the higher educational establishments in the districts beyond the Alps and the Rhine which had been annexed to France, and to report upon the means by which these could be affiliated with the central university. Three separate reports on this subject were published by him.

In his capacity, again, of perpetual secretary of the Institute, he not only prepared a number of éloges historiques on deceased members of the Academy of Sciences, but he was the author of a number of reports on the history of the physical and natural sciences, the most important of these being the Rapport historique sur le progrès des sciences physiques depuis 1789, published in 1810.

Prior to the fall of Napoleon (1814) he had been admitted to the council of state, and his position remained unaffected by the restoration of the Bourbons. He was elected chancellor of the university, in which capacity he acted as interim president of the council of public instruction, whilst he also, as a Lutheran, superintended the faculty of Protestant theology. In 1819 he was appointed president of the committee of the interior, and retained the office until his death.

In 1826 he was made grand officer of the Legion of Honour; he was subsequently appointed president of the council of state. He served as a member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres from 1830 to his death. A member of the Doctrinaires, he was nominated to the ministry of the interior in the beginning of 1832.

Named after Cuvier

Cuvier is commemorated in the naming of several animals; they include Cuvier's beaked whale (which he first thought to be extinct), Cuvier's Gazelle, Cuvier's toucan, Cuvier's bichir, Cuvier's dwarf caiman, Galeocerdo cuvier (tiger shark), and Anolis cuvieri, a lizard from Puerto Rico. There are also some extinct animals named after Cuvier, such as the South American giant sloth Catonyx cuvieri.

Cuvier Island in New Zealand was named after Cuvier by D'Urville[43]

Principal scientific publications

- Tableau élémentaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux (1797–1798)

- Leçons d'anatomie comparée (5 volumes, 1800–1805) (text in French)

- Essais sur la géographie minéralogique des environs de Paris, avec une carte géognostique et des coupes de terrain, with Alexandre Brongniart (1811)

- Le Règne animal distribué d'après son organisation, pour servir de base à l'histoire naturelle des animaux et d'introduction à l'anatomie comparée (4 volumes, 1817)

- Recherches sur les ossemens fossiles de quadrupèdes, où l'on rétablit les caractères de plusieurs espèces d'animaux que les révolutions du globe paroissent avoir détruites (4 volumes, 1812) (text in French) 2 3 4

- Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire et à l'anatomie des mollusques (1817)

- Éloges historiques des membres de l'Académie royale des sciences, lus dans les séances de l'Institut royal de France par M. Cuvier (3 volumes, 1819–1827) Vol. 1 , Vol. 2, and Vol. 3 , (text in French)

- Théorie de la terre (1821)

- Discours sur les révolutions de la surface du globe et sur les changements qu'elles ont produits dans le règne animal (1822). New edition: Christian Bourgeois, Paris, 1985. (text in French)

- Histoire des progrès des sciences naturelles depuis 1789 jusqu'à ce jour (5 volumes, 1826–1836)

- Histoire naturelle des poissons (11 volumes, 1828–1848), continued by Achille Valenciennes

- Histoire des sciences naturelles depuis leur origine jusqu'à nos jours, chez tous les peuples connus, professée au Collège de France (5 volumes, 1841–1845), edited, annotated, and published by Magdeleine de Saint-Agit

- Cuvier's History of the Natural Sciences: twenty-four lessons from Antiquity to the Renaissance [edited and annotated by Theodore W. Pietsch, translated by Abby S. Simpson, foreword by Philippe Taquet], Paris: Publications scientifiques du Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, 2012, 734 p. (coll. Archives; 16) ISBN 978-2-85653-684-1

Cuvier also collaborated on the Dictionnaire des sciences naturelles (61 volumes, 1816–1845) and on the Biographie universelle (45 volumes, 1843-18??)

See also

- Saartjie Baartman, the "Hottentot Venus" whose body Cuvier examined

- Frédéric Cuvier, also a naturalist, was Georges Cuvier's younger brother.

- History of paleontology for more on the impact of Cuvier's scientific ideas

References

- ^ Faria 2012, pp. 64–74

- ^ Lee 1833

- ^ a b Lee 1833, p. 8

- ^ 'Extrait du 7.e Registre des Enfants baptises dans l'Eglise françoise de Saint Martin de la Ville de Montbéliard deposé aux Archives de l'Hôtel de Ville', Culture.gouv.fr

- ^ Montbéliard au XVIIIe siècle

- ^ a b c Lee 1833, p. 11

- ^ [1] Philippe Taquet: Les années de jeunesse de Georges Cuvier p. 217 online

- ^ Lee 1833, p. 22

- ^ Lee 1833, p. 22, footnote

- ^ Lee 1833, p. 23

- ^ Andrew Dickson White, A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom Appleton (1922) Vol.1 p.64

- ^ Coleman 1962, p. 16

- ^ Larson 2004, p. 8

- ^ Taquet 2009, p. 127

- ^ Waggoner 1996

- ^ Zimmer 2006, p. 19

- ^ Rudwick 1997, p. 229

- ^ Rudwick 1997, pp. 228–229

- ^ Turner 1984, p. 35

- ^ Kuznar 2008, p. 37

- ^ Hall 1999, p. 62

- ^ CNRS.fr

- ^ Victorianweb.org

- ^ Gillispie 1996, p. 103

- ^ Cuvier 1818, p. 130

- ^ Cuvier 1818, pp. 133–134; English translation quoted from Cuvier 1827, p. 121

- ^ Cuvier 1827, p. 407

- ^ Larson 2004, pp. 9–10

- ^ Rudwick 1997, pp. 22–24

- ^ Baron Georges Cuvier A Discourse on the Revolutions of the Surface of the Globe.

- ^ Rudwick 1997, pp. 129–133

- ^ Cuvier 1801

- ^ Cuvier 1809

- ^ Rudwick 1997, p. 158

- ^ Rudwick 1997, p. 36

- ^ See discussion in Reiss 2009

- ^ McClellan 2001

- ^ a b Jackson & Weidman 2005, pp. 41–42

- ^ Kidd 2006, p. 28

- ^ Isaac 2006, p. 105

- ^ Georges Cuvier, Tableau elementaire de l'histoire naturelle des animaux (Paris, 1798) p.71

- ^ Georges Cuvier, The animal kingdom: arranged in conformity with its organization, Translated from the French by H. M Murtrie, p 50.

- ^ New Zealand Lighthouses

Bibliography

- Faria, F. (2012). Georges Cuvier: do estudo dos fósseis à paleontologia. São Paulo: Scientiae Studia & Editora 34.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Coleman, W. (1962). Georges Cuvier, Zoologist. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cuvier, G. (1801). "Reptile volant". Journal de Physique, de Chimie et d'Histoire Naturelle. 52: 253–267.

Extrait d'un ouvrage sur les espèces de quadrupèdes dont on a trouvé les ossemens dans l'intérieur de la terre

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cuvier, G. (1809). "Mémoire sur le squelette fossile d'un reptile volant des environs d'Aichstedt, que quelques naturalistes ont pris pour un oiseau, et dont nous formons un genre de Sauriens, sous le nom de Ptero-Dactyle". Annales du Muséum national d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris. 13: 424–437.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cuvier, G. (Baron) (1818). Essay on the Theory of the Earth. New York: Kirk & Mercein.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cuvier, G. (Baron) (1827). Essay on the Theory of the Earth (5th ed.). London: T. Cadell.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gillispie, Charles Coulson (1996). Genesis and Geology. Harvard historical studies. Vol. 58. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-34481-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hall, Brian Keith (1999). Evolutionary Developmental Biology (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-0-412-78590-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Isaac, Benjamin H. (2006). The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12598-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jackson, John P.; Weidman, Nadine M. (2005). Race, Racism, and Science: Social Impact and Interaction. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3736-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kidd, Colin (2006). The Forging of Races: Race and Scripture in the Protestant Atlantic World, 1600–2000. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79324-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kuznar, Lawrence A. (30 September 2008). Reclaiming a Scientific Anthropology. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-1109-7. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Larson, Edward J. (2004). Evolution: The Remarkable History of a Scientific Theory. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-64288-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lee, Mrs. R. (1833). Memoirs of Baron Cuvier. London: Longman, Reese, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longman.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McClellan, C. (2001). "The legacy of Georges Cuvier in Auguste Comte's natural philosophy". Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science Part A. 32 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1016/S0039-3681(00)00041-8.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reiss, John O. (2009). Not by Design: Retiring Darwin's Watchmaker. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rudwick, Martin J. S. (1997). Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophes. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-73106-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Russell, E. S. (1982). Form and Function: a Contribution to the History of Animal Morphology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Taquet, Phillipe (2009). "Cuvier's attitude toward creation and the biblical Flood". In Kölbl-Ebert, Martina (ed.). Geology and religion: a history of harmony and hostility. Special Publication 310. London: Geological Society of London. ISBN 978-1-86239-269-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Turner, John (February 9, 1984), "Why we need evolution by jerks", New Scientist, vol. 101, no. 1396, pp. 34–35, retrieved November 4, 2012

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Waggoner, Ben (1996). "Georges Cuvier (1769–1832)". University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zimmer, Carl (2006). Evolution: the Triumph of an Idea. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-113840-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Further reading

- Histoire des travaux de Georges Cuvier (3rd ed.). Paris. 1858.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cuvier, G. (1815). Essay on the Theory of the Earth. Blackwood (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009). ISBN 978-1-108-00555-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - de Candolle, A. P. (1832). "Mort de G. Cuvier". Bibliothique universelle. Vol. 59. p. 442.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flourens, P. J. M. (1834). Éloge historique de G. Cuvier. Published as an introduction to the Éloges historiques of Cuvier.

- Laurillard, C. L. (1836). "Cuvier". Biographie universelle. Vol. Supp. vol. 61.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Outram, Dorinda (1984). Georges Cuvier: Vocation, Science and Authority in Post-Revolutionary France. Palgrave Macmillan.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Corsi, Pietro (2005). Rapport historique sur les progrès des sciences naturelles depuis 1789, et sur leur état actuel, présenté à Sa Majesté l'Empereur et Roi, en son Conseil d'État, le 6 février 1808, par la classe des sciences physiques et mathématiques de l'Institut... conformément à l'arrêté du gouvernement du 13 ventôse an X. Paris.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Taquet, Philippe (2006). Georges Cuvier, Naissance d'un Génie. Paris: Odile jacob. ISBN 2-7381-0969-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- 1769 births

- 1832 deaths

- People from Montbéliard

- Barons of France

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- Chancellors of the University of Paris

- Collège de France faculty

- Deaths from cholera

- Foreign Members of the Royal Society

- Foreign Members of the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences

- French ichthyologists

- French Lutherans

- French malacologists

- French paleontologists

- French Protestants

- French ornithologists

- French naturalists

- French scientists

- French zoologists

- Grand Officiers of the Légion d'honneur

- Infectious disease deaths in France

- Members of the Académie française

- Members of the French Academy of Sciences

- Members of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- Peers of France

- Teuthologists

- 18th-century French writers

- 19th-century French writers