Scottish National Antarctic Expedition

The Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (SNAE), 1902–1904, was organised and led by William Speirs Bruce, a natural scientist and former medical student from the University of Edinburgh. Although overshadowed in terms of prestige by Robert Falcon Scott's concurrent Discovery Expedition, the SNAE completed a full programme of exploration and scientific work. Its achievements included the establishment of a staffed meteorological station, the first in Antarctic territory, and the discovery of new land to the east of the Weddell Sea. Its large collection of biological and geological specimens, together with those from Bruce's earlier travels, led to the establishment of the Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory in 1906.

Bruce had spent most of the 1890s engaged on expeditions to the Antarctic and Arctic regions, and by 1899 was Britain's most experienced polar scientist. In March of that year, he applied to join the Discovery Expedition; however, his proposal to extend that expedition's field of work into the Weddell Sea quadrant, using a second ship, was dismissed as "mischievous rivalry" by Royal Geographical Society (RGS) president Sir Clements Markham. Bruce reacted by obtaining independent finance; his venture was supported and promoted by the Royal Scottish Geographical Society.

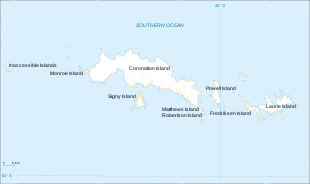

The expedition has been described as "by far the most cost-effective and carefully planned scientific expedition of the Heroic Age."[1] Despite this, Bruce received no formal honour or recognition from the British Government, and the expedition's members were denied the prestigious Polar Medal despite vigorous lobbying. After the SNAE, Bruce led no more Antarctic expeditions, although he made regular Arctic trips. His focus on serious scientific exploration was out of fashion with his times, and his achievements, unlike those of the polar adventurers Scott, Shackleton and Amundsen, soon faded from public awareness. The SNAE's permanent memorial is the Orcadas weather station, which was set up in 1903 as "Omond House" on Laurie Island, South Orkneys, and has been in continuous operation ever since.

Background to the expedition

During his student years – the 1880s and early 1890s – William Speirs Bruce built up his knowledge of the natural sciences and oceanography, by studying at summer courses under distinguished tutors such as Patrick Geddes and John Arthur Thomson. He also spent time working voluntarily under the oceanographer Dr John Murray, helping to classify specimens collected during the Challenger expedition.[2] In 1892 Bruce gave up his medical studies altogether, and embarked on a voyage to the Antarctic in the whaler Balaena, as part of the 1892–1893 Dundee Whaling Expedition.[3] On his return, he began organising an expedition of his own to South Georgia, claiming that "the taste I have had has made me ravenous",[4] but he could not obtain funding. He then worked at a meteorological station on the summit of Ben Nevis,[5] before joining the Jackson–Harmsworth Arctic Expedition to Franz Josef Land as a scientific assistant.[6] Between 1897 and 1899 he made further Arctic trips, to Spitsbergen and to Novaya Zemlya, first on a private trip organised by Major Andrew Coats, later as a scientist on the Arctic survey vessel Princess Alice. This vessel was owned by Prince Albert of Monaco, a renowned oceanographer who became a friend and supporter of Bruce.[7]

After returning from the Arctic in 1899, Bruce sent a lengthy letter to the Royal Geographical Society in London, applying for a scientific post on the major Antarctic expedition (later to be known as the Discovery Expedition), which the RGS was then organising.[8] His recent experiences made it "unlikely that there was any other person in the British Isles at that time better qualified".[8] Bruce's letter, which detailed all his relevant qualifications, was acknowledged but not properly answered until more than a year had passed. By then, Bruce's ideas had progressed away from his original expectation of a junior post on the scientific staff. He now proposed a second ship for the expedition, separately financed from Scottish sources, which would work in the Weddell Sea quadrant while the main ship was based in the Ross Sea. This proposal was denounced by RGS president Sir Clements Markham as "mischievous" and, after some heated correspondence, Bruce resolved to proceed independently.[9] In this way the idea of a distinctive Scottish National Antarctic expedition was born. Bruce was supported by the wealthy Coats family,[A] who were prepared to give whole-hearted financial backing to a Scottish expedition under his leadership.[10] However, as a result, he had acquired the lasting enmity of Markham.[1]

Preparations

Scotia

In late 1901, Bruce purchased a Norwegian whaler, Hekla, at a cost of £2,620 (approximately £360,000 as of 2024[11]).[10] During the following months, the ship was completely rebuilt as an Antarctic research vessel, with two laboratories, a darkroom, and extensive specialist equipment. Two huge revolving cylinders, each carrying 6,000 fathoms (36,000 ft; 11,000 m) of cable, were fitted to the deck to enable deep-sea trawling for marine specimens. Other equipment was installed for making depth soundings, for the collection of sea water and sea-bottom samples, and for meteorological and magnetic observations.[12] The hull was reinforced to withstand the pressures of Antarctic ice, and the ship was re-rigged as a barque with auxiliary engines. This work increased the cost of the ship to £16,700 (approximately £2,290,000 as of 2024[11]), which was met by the Coats family who altogether donated £30,000 towards the total expedition costs of £36,000. Renamed Scotia, the ship was ready for her sea trials in August 1902.[10]

Personnel

The expedition's scientific staff consisted of six persons, including Bruce. The zoologist was David Wilton who, like Bruce, had been a member of the Jackson-Harmsworth Expedition. He had acquired skiing and sledging skills during several years living in northern Russia. Robert Rudmose-Brown, of University College, Dundee, and formerly an assistant in the Botany Department at the British Museum, was the party's botanist. Dr James Harvie Pirie, who had worked in the Challenger office under John Murray, was geologist, bacteriologist, and the expedition's medical officer. Robert Mossman directed meteorological and magnetic work, and Alastair Ross, a medical student, was taxidermist.[13]

Bruce appointed Thomas Robertson as Scotia's captain. Robertson was an experienced Antarctic and Arctic sailor who had commanded the whaling ship Active on the Dundee Whaling Expedition.[14] The rest of the 25 officers and men, who signed for three-year engagements, were all Scotsmen, many used to sailing in icy waters on whaling voyages.[B]

Objectives

The objectives of the expedition were published in the Scottish Geographical Magazine and in the RGS Geographical Journal, in October 1902. They included the establishment of a winter station "as near to the South Pole as is practicable",[15] deep sea and other research of the Antarctic Ocean, and systematic observations and research of meteorology, geology, biology, topography and terrestrial physics.[10] The essentially Scottish character of the expedition was expressed in The Scotsman shortly before departure: "The leader and all the scientific and nautical members of the expedition are Scots; the funds have been collected for the most part on this side of the Border; it is a product of voluntary effort, and unlike the expedition which will be simultaneously employed in the exploration of the Antarctic, it owes nothing to Government help".[16]

As the work of the expedition would be mainly at sea, or within the confines of the winter station, only a few dogs were taken, to facilitate the occasional sledge journey. Rudmose Brown records that of the original eight dogs, four survived the expedition; they "pulled well in harness, their only weak point being their paws which... were apt to be cut when on rough ice".[17]

Expedition

First voyage, 1902–1903

Scotia left Troon, Scotland, on 2 November 1902. On her way southward she called at the Irish port of Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire),[C] at Funchal in Madeira, and then the Cape Verde Isles[18] before an unsuccessful attempt was made to land at the tiny, isolated equatorial archipelago known as St Paul's Rocks. This attempt almost cost the life of the expedition's geologist and medical officer, James Harvie Pirie, who was fortunate to escape from the shark-infested seas after misjudging his leap ashore.[19][20] Scotia reached Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands on 6 January 1903, where she re-provisioned for the Antarctic journey ahead.[21]

On 26 January, Scotia set sail for Antarctic waters. The crew had to manoeuvre round heavy pack ice on 3 February, 25 miles (40 km) north of the South Orkney Islands.[22] Next day, Scotia was able to move southward again and land a small party on Saddle Island, South Orkney Islands, where a large number of botanical and geological specimens were gathered.[22] Ice conditions prevented any further progress until 10 February, after which Scotia continued southward, "scudding along at seven knots under sail".[22] On 17 February the position was 64°18′S, and five days later they passed 70°S, deep within the Weddell Sea. Shortly after this, with new ice forming and threatening the ship, Robertson turned northward, having reached 70°25′S.[22]

Having failed to find land, the expedition had to decide where to winter. The matter was of some urgency, since the sea would soon be freezing over, with the risk of the ship becoming trapped. Bruce decided to head back to the South Orkneys and find an anchorage there.[23] In contrast to his stated object, to winter as far south as possible, the South Orkneys were more than 2,000 miles (3,200 km) from the South Pole, but the northerly location had advantages. The relatively brief period during which the ship would be frozen in would allow more time for trawling and dredging operations early in the year.[23] Also, the islands were well-situated as a site for a meteorological station – their relative proximity to the South American mainland opened the prospect of establishing a permanent station.[24]

It took a month of hard sailing before Scotia reached the islands. After several foiled attempts to locate a suitable anchorage, and with its rudder seriously damaged by ice, the ship finally found a sheltered bay on the southern shore of Laurie Island, the most easterly of the South Orkneys chain. On 25 March the ship safely anchored,[25] settling into the ice 1⁄4 mi (400 m) from shore. She was then rapidly converted to winter quarters, with engines dismantled, boilers emptied, and a canvas canopy enclosing the deck.[26] Bruce instituted a comprehensive programme of work, involving meteorological readings, trawling for marine samples, botanical excursions, and the collection of biological and geological specimens.[27] The major task completed during this time was the construction of living accommodations for those who would remain on Laurie Island to operate the proposed meteorological laboratory. The 20-by-20-foot (6 by 6 m) building – its walls built from local materials using the dry stone method, and roof improvised from wood and canvas sheeting – had two windows and was fitted for six people.[28] It was christened "Omond House" after Robert Omond, director of the Edinburgh Observatory and a supporter of the expedition.[29] Rudmose Brown wrote: "Considering that we had no mortar and no masons' tools it is a wonderfully fine house and very lasting. I should think it will be standing a century hence ..."[28]

In general, the party maintained excellent health. The exception was the ship's engineer, Allan Ramsay, who had been taken ill with a heart condition in the Falklands during the outward voyage. He chose to remain with the expedition, but he grew steadily weaker as winter progressed. He died on 6 August, and was buried on the island.[30]

As winter turned to spring the level of activity increased, and there were numerous sledge journeys,[17] including some to neighbouring islands. Near Omond House, a wooden hut was constructed for magnetic observations and a cairn was built, 9 ft (2.7 m) high, on top of which the Union Flag and the Saltire were displayed.[30] Scotia was made seaworthy again, but remained icebound throughout September and October; it was not until 23 November that strong winds broke up the bay ice, allowing her to float free. Four days later she departed for Port Stanley, leaving a party of six under Robert Mossman at Omond House.[30]

Buenos Aires, 1903–1904

On 2 December 1903, the expedition reached Port Stanley, where they received their first news from the outside world since leaving the Cape Verde Islands. After a week's rest, Scotia departed for Buenos Aires, where she was to be repaired and provisioned for another season's work. Bruce had further business in the city; he intended to persuade the Argentine government to assume responsibility for the Laurie Island meteorological station after the expedition's departure.[31] During the voyage to Buenos Aires, Scotia ran aground in the Río de la Plata estuary, and was stranded for several days before floating free and being assisted into port by a tug, on 24 December.[32]

During the following four weeks, while the ship was dry-docked, Bruce negotiated with the Argentine government over the future of the weather station. He was assisted by the British resident minister, the British Consul, and Dr W. G. Davis who was director of the Argentine Meteorological Office. When contacted by cable, the British Foreign Office registered no objection to this scheme.[31] On 20 January 1904, Bruce confirmed an agreement whereby three scientific assistants of the Argentine government would travel back to Laurie Island to work for a year, under Robert Mossman, as the first stage of an annual arrangement. He then formally handed over the Omond House building, its furnishings and provisions, and all magnetic and meteorological instruments, to the Argentine government.[31] The station, renamed Orcadas Base, has remained operational ever since, having been rebuilt and extended several times.[31]

Several of the original crew left during the Buenos Aires interlude, some through illness and one discharged for misconduct, and replacements were recruited locally.[B] Scotia left for Laurie Island on 21 January, arriving on 14 February. A week later, having settled the meteorological party, who were to be relieved a year later by the Argentine gunboat Uruguay, Scotia set sail for her second voyage to the Weddell Sea.[33]

Second voyage, 1904

Scotia headed south-east, towards the eastern waters of the Weddell Sea, in calm weather. No pack ice was encountered before they were south of the Antarctic Circle,[34] and they were able to proceed smoothly until, on 3 March, heavy pack ice stopped the ship at 72°18'S, 17°59'W. A sounding was taken, revealing a sea-depth of 1,131 fathoms (6,786 ft; 2,068 m), compared to the 2,500 fathoms (15,000 ft; 4,600 m) which had been the general measurement up to that date.[35] This suggested that they were approaching land. A few hours later, they reached an ice barrier, which blocked progress towards the south-east. Over the following days, they tracked the edge of this barrier southwards for some 150 miles (240 km). A sounding 2+1⁄2 miles (4.0 km) from the barrier edge gave a depth of only 159 fathoms (954 ft; 291 m), which strongly indicated the presence of land behind the barrier.[36] The outlines of this land soon became faintly visible, and Bruce named it Coats Land after his chief sponsors.[35] This was the first positive indicator of the eastern limits of the Weddell Sea at high latitude, and suggested that the sea might be considerably smaller than had been previously supposed.[36][D] A projected visit to Coats Land by a sledging party was abandoned by Bruce because of the state of the sea ice.[37]

On 9 March 1904, Scotia reached its most southerly latitude of 74°01'S. At this point, the ship was held fast in the pack ice, and the prospect loomed of becoming trapped for the winter. It was during this period of inactivity that bagpiper Gilbert Kerr was photographed playing the bagpipes to a penguin.[35] On 13 March the ship broke free and began to move slowly north-eastward under steam.[38] Throughout this part of the voyage a regular programme of depth soundings, trawls, and sea-bottom samples provided a comprehensive record of the oceanography and marine life of the Weddell Sea.[39]

Scotia headed for Cape Town by a route that took it to Gough Island, an isolated mid-Atlantic volcanic projection that had never been visited by a scientific party. On 21 April, Bruce and five others spent a day ashore, collecting specimens.[40] The ship arrived in Cape Town on 6 May.[41] After carrying out further research work in the Saldanha Bay area, Scotia sailed for home on 21 May.[42]

On the voyage home the party called at Saint Helena and visited Napoleon's exile home which they found neglected and in disrepair. On 7 June the ship reached Ascension Island where they were impressed by the sight of giant turtles, some of them 4 ft (1.2 m) across. The final port of call was at Horta in the Azores, where they stopped briefly on 5 July before heading for home.[43]

Homecoming and after

The expedition was warmly received on its return to the Clyde on 21 July 1904.[44][45] A formal reception for 400 people was held at the Marine Biological Station, Millport, at which John Murray read a telegram of congratulation from King Edward VII.[44] Bruce was presented with the Royal Scottish Geographical Society's gold medal, and Captain Robertson with the silver medal.[46]

Following the expedition, more than 1,100 species of animal life, 212 of them previously unknown to science, were catalogued;[47] there was no official acknowledgement from London, where under the influence of Markham the work of the SNAE tended to be ignored or denigrated.[48] Its members were not awarded the prestigious RGS Polar Medals, which were bestowed on members of the Discovery Expedition when it returned home two months after Scotia. Polar Medals would also be awarded after each of Sir Ernest Shackleton's later expeditions, and after Douglas Mawson's Australasian expedition. Bruce fought unavailingly for years to right what he considered a grave injustice, a slight on his country and on his expedition.[49][E] Some of the aversion of the London geographical establishment may have arisen from Bruce's overt Scottish nationalism, reflected in his own prefatory note to Rudmose Brown's expedition history, in which he said: "While Science was the talisman of the Expedition, Scotland was emblazoned on its flag; and it may be that, in endeavouring to serve humanity by adding another link to the golden chain of science, we have also shown that the nationality of Scotland is a power that must be reckoned with".[50]

A significant consequence of the expedition was the establishment by Bruce, in Edinburgh, of the Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory, which was formally opened by Prince Albert of Monaco in 1906.[51] The Laboratory served as a repository for the large collection of biological, zoological and geological specimens amassed during the Scotia voyages, and also during Bruce's earlier Arctic and Antarctic travels. It was also a base from which the scientific reports of the SNAE could be prepared, and it served as general headquarters where polar explorers could meet – Nansen, Amundsen and Shackleton all visited – and where other Scottish polar ventures could be planned and organised.[51]

Although Bruce continued to visit the Arctic for scientific and commercial purposes, he never led another Antarctic expedition, his plans for a transcontinental crossing being stifled through lack of funding. The SNAE scientific reports took many years to complete; most were published between 1907 and 1920, but one volume was delayed until 1992.[51] A proposal to convert the Laboratory into a permanent Scottish National Oceanographic Institute failed to come to fruition and, because of difficulties with funding, Bruce was forced to close it down in 1919.[51] He died two years later, aged 54.[52]

By this time, the Scotia expedition was barely remembered, even in Scotland, and it has remained overshadowed in polar histories by the more glamorous adventures of Scott and Shackleton.[1] In these histories it is usually confined to a brief mention or footnote, with little attention given to its achievements.[F] Bruce lacked charisma, had no public relations skills ("...as prickly as the Scottish thistle itself", according to a lifelong friend[1]), and tended to make powerful enemies.[1] In the words of oceanographer Professor Tony Rice,[53] his expedition fulfilled "a more comprehensive programme than that of any previous or contemporary Antarctic expedition".[1]

The expedition ship Scotia was requisitioned during the Great War, and saw service as a freighter. On 18 January 1916 she caught fire, and was burned out on a sandbank in the Bristol Channel.[54] One hundred years after Bruce, a 2003 expedition, in a modern version of Scotia, used information collected by the SNAE as a basis for examining climate change in South Georgia during the past century. This expedition asserted that its contribution to the international debate on global warming would be a fitting testament to the SNAE's pioneering research.[55]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ The Coats family were wealthy Clydeside thread manufacturers, with a taste for adventure, who had also founded the Coats Observatory at Paisley. See Goodlad, Planning and financing the expedition.

- ^ a b See Speak, pp. 77–78 for full list of officers and crew.

- ^ Dún Laoghaire was then known by its British name, Kingstown.

- ^ The presence of land in this location was later confirmed by the expeditions of Wilhelm Filchner (1911–1913) and Ernest Shackleton (1914–1917).

- ^ In 1906 Bruce commissioned his own silver medal, which he awarded to scientific and crew members of the expedition. Speak, pp. 126–127.

- ^ A typical reference is Elspeth Huxley's, in her 1977 biography of Captain Scott: "There was Bruce’s venture shortly to sail in the Scotia to the Weddell Sea; this, too, got trapped in sea-ice and returned without ever reaching land". Huxley, Scott of the Antarctic, p. 52.

References

- ^ a b c d e f Speak, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Speak, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Speak, pp. 31–34.

- ^ Speak, p. 36.

- ^ Speak, pp. 42–45.

- ^ Speak, pp. 46–51.

- ^ Speak, pp. 52–58.

- ^ a b Speak, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Speak, pp. 71–74.

- ^ a b c d Speak, pp. 75–76.

- ^ a b UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Speak, p. 29.

- ^ Speak, p. 79.

- ^ Speak, p. 80.

- ^ a b Rudmose Brown, p. 76.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, pp. 15–20.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Goodlad, The voyage south.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d Rudmose Brown, pp. 28–33.

- ^ a b Rudmose Brown, p. 34.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, p. 57.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, p. 45.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, pp. 46–50.

- ^ a b Speak, p. 85.

- ^ Glasgow Digital Library, Omond House.

- ^ a b c Speak, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b c d Speak, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, p. 105.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, pp. 118–120.

- ^ a b c Rudmose Brown, pp. 120–123.

- ^ a b Rudmose Brown, p. 121.

- ^ Speak, p. 93.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, p. 122.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, pp. 123–126.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, pp. 132–134.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, p. 138.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, pp. 140–142.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, pp. 145, 148–153, 156–158.

- ^ a b Speak, p. 95.

- ^ "Scottish Antarctic Expedition. Return of the Scotia". The Glasgow Herald. 22 July 1904. p. 10. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ^ Speak, p. 9.

- ^ NAHSTE, William Speirs Bruce.

- ^ Speak, p. 123.

- ^ Speak, pp. 125–131.

- ^ Rudmose Brown, p. xiii.

- ^ a b c d Speak, pp. 97–101.

- ^ Speak, p. 133.

- ^ Author of Deep Ocean (Natural History Museum, London 2000, ISBN 0-565-09150-6)

- ^ Erskin & Kjær 2005.

- ^ Collingridge, Diary of Climate Change.

Sources

Books

- Fiennes, Ranulph (2003). Captain Scott. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-82697-5.

- Huxley, Elspeth (1977). Scott of the Antarctic. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77433-6.

- Rudmose Brown, R. N.; Pirie, J. H.; Mossman, R. C. (2002). The Voyage of the Scotia. Edinburgh: Mercat Press. ISBN 1-84183-044-5.

- Speak, Peter (2003). William Speirs Bruce: Polar Explorer and Scottish Nationalist. Edinburgh: NMS Publishing. ISBN 1-901663-71-X.

Online

- Collingridge, Vanessa (9 May 2003). "Diary of Climate Change". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- Erskin, Angus B.; Kjær, Kjell-G. (2005). "The Polar Ship Scotia". Polar Record. 41 (2). Cambridge University Press: 131–140. Bibcode:2005PoRec..41..131E. doi:10.1017/S0032247405004237. S2CID 129860880.

- Goodlad, James A. (2003). Scotland and the Antarctic, Section 5: Voyage of the 'Scotia' – Planning and financing the expedition. Royal Scottish Geographical Society. ISBN 0-904049-04-3. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Goodlad, James A. (2003). Scotland and the Antarctic, Section 5: Voyage of the 'Scotia' – The voyage south. Royal Scottish Geographical Society. ISBN 0-904049-04-3. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Measuring Worth". Institute for the Measurement of Worth. Retrieved 12 July 2008.

- "Voyage of the Scotia 1902–04: The Antarctic. The hut known as Omond House on Laurie Island in the South Orkney Islands, 1902–04". Glasgow Digital Library. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- "William Speirs Bruce, 1867–1921. Polar explorer and oceanographer: Biographical Information". Navigational Aids for the History of Science, Technology & the Environment (University of Edinburgh). Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

External links

Media related to Scottish National Antarctic Expedition at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Scottish National Antarctic Expedition at Wikimedia Commons