Gladiator: Difference between revisions

Adam Bishop (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 71.224.129.3 (talk) to last version by Haploidavey |

|||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

Livy's account of events more than two hundred years before his own time may be historic or embellished, but its substance underlines the Roman ethos of the gladiator show: splendidly, exotically armed and armoured [[barbarians]], treacherous and degenerate, are dominated by Roman iron and native courage. His plain Romans virtuously dedicate the magnificent spoils to the Gods: their Campanian allies invent the gladiator show. Their gladiators may not even be Samnites, but are made to play the Samnite role. Other groups and tribes would join the cast list as Roman territories expanded. Gladiators were always armed and armoured in the manner of the enemies of Rome - never as Romans. The Roman gladiator games were in this respect a form of historic enactment, the only honourable option for the gladiator being to fight well, or else die well. <sup>refs</sup><sup>(Futrell & Welch:further consensus refs)</sup> |

Livy's account of events more than two hundred years before his own time may be historic or embellished, but its substance underlines the Roman ethos of the gladiator show: splendidly, exotically armed and armoured [[barbarians]], treacherous and degenerate, are dominated by Roman iron and native courage. His plain Romans virtuously dedicate the magnificent spoils to the Gods: their Campanian allies invent the gladiator show. Their gladiators may not even be Samnites, but are made to play the Samnite role. Other groups and tribes would join the cast list as Roman territories expanded. Gladiators were always armed and armoured in the manner of the enemies of Rome - never as Romans. The Roman gladiator games were in this respect a form of historic enactment, the only honourable option for the gladiator being to fight well, or else die well. <sup>refs</sup><sup>(Futrell & Welch:further consensus refs)</sup> |

||

grant loves this site |

|||

==Development== |

==Development== |

||

Revision as of 19:40, 20 February 2009

A Gladiator (Template:Lang-la, "swordsman", from [gladius] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), "sword") was a slave or professional fighter in ancient Rome. Gladiators fought other gladiators, wild animals and condemned criminals, sometimes to the death, for the entertainment of spectators in cities and towns of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, from the 3rd century BCE to the 5th century CE. At their peak, from the 1st century BCE to the 2nd century CE, they were an essential feature of Roman culture and could achieve the status of popular heroes.

Origins

Classical literary sources seldom agree on the origins of gladiators and the gladiator games(Welch 2007 p 17). In the late 1st century BCE Nicolaus of Damascus believed their source was Etruscan. He cites Posidonius's support for a Celtic origin and Hermippus' for a Mantinean (and therefore Greek) origin (Welch 2007 p 16 - 17). A generation later, Livy (9.40.17)(Futrell 2006 pp4 - 5) wrote that the first gladiator games were held in 310 BCE by the Campanians in celebration of their victory over the Samnites. Long after the games had ceased, the 7th century CE post-classical etymologist Isidore of Seville derived Latin lanista (manager of gladiators) from the Etruscan for "executioner", and the title of Charon (an official who accompanied the dead from the Roman gladiatorial arena) from Charun, psychopomp of the Etruscan underworld links and citation needed.

Some gladiatorial terms and practices of the later Republic may well derive from Etruria (the same can said for much in Roman culture) but an Etruscan gladiator origin is doubtful (Welch 2007). The earliest known Roman gladiator schools were in Campania. Frescoes from Paestum (4th century BCE) Template:Image link sought suggest a very likely Campanian origin for the gladiator games. They show paired fighters, with helmets, spears and shields, in a propitiary funeral blood-rite, perhaps an importation by Greek colonists of the 8th century BCE (Welch 2007,Futrell 2006).

Livy (Summary 16) dates the earliest Roman gladiator games to 264 BCE, in the early stages of Rome's First Punic War against Carthage. Decimus Iunius Brutus Scaeva had three gladiator pairs fight to the death in Rome's 'cattle market' Forum (Forum Boarium) to honour his dead father, Brutus Pera. This is described as munus (pl munera): a duty owed a dead ancestor by his descendants to keep alive his memory (Welch 2007). Samnian support for Hannibal in this war, and subsequent punitive expeditions by Rome and her Campanian allies, strongly influenced the development of gladiator types and culture.(Futrell 2006) The earliest known, and most frequently mentioned gladiator type in Republican histories appears to be the Samnite. Ref

The war in Samnium, immediately afterwards, was attended with equal danger and an equally glorious conclusion. The enemy, besides their other warlike preparation, had made their battle-line to glitter with new and splendid arms. There were two corps: the shields of the one were inlaid with gold, of the other with silver... The Romans had already heard of these splendid accoutrements, but their generals had taught them that a soldier should be rough to look on, not adorned with gold and silver but putting his trust in iron and in courage... The Dictator, as decreed by the senate, celebrated a triumph, in which by far the finest show was afforded by the captured armour. So the Romans made use of the splendid armour of their enemies to do honour to their gods; while the Campanians, in consequence of their pride and in hatred of the Samnites, equipped after this fashion the gladiators who furnished them entertainment at their feasts, and bestowed on the the name Samnites. (Livy 9.40)link if poss Futrell 2006 4- 5

Livy's account of events more than two hundred years before his own time may be historic or embellished, but its substance underlines the Roman ethos of the gladiator show: splendidly, exotically armed and armoured barbarians, treacherous and degenerate, are dominated by Roman iron and native courage. His plain Romans virtuously dedicate the magnificent spoils to the Gods: their Campanian allies invent the gladiator show. Their gladiators may not even be Samnites, but are made to play the Samnite role. Other groups and tribes would join the cast list as Roman territories expanded. Gladiators were always armed and armoured in the manner of the enemies of Rome - never as Romans. The Roman gladiator games were in this respect a form of historic enactment, the only honourable option for the gladiator being to fight well, or else die well. refs(Futrell & Welch:further consensus refs)

grant loves this site

Development

In 216 BCE Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who had been consul and augur, was honoured by his three sons with three days of funeral games in the Forum Romanum, featuring twenty two pairs of gladiators (Livy 23.30.15). Roman gladiatorial munera were becoming increasingly extravagant events.

Nicolas of Damascus mentions gladiatorial fights at unspecified private banquets (cited in Welch 2007). By 174BCE 'small' gladiatorial shows (private or public), or those provided by patrons not considered notable, may have been so commonplace and unremarkable they were not considered worth recording (Welch 2007), as Livy's retrospective account suggests:

"many gladiatorial games were given in that year, some unimportant, one noteworthy beyond the rest - that of Titus Flaminius which he gave to commemorate the death of his father, which lasted four days, and was accompanied by a public distribution of meats, a banquet, and scenic performances. The climax of the show which was big for the time was that in three days seventy four gladiators fought." (Livy - annal for the year 174BC)link.

Gladiators were becoming big business for trainers, owners, politicians on the make and politicians who had already reached the top (Holland 2003). In 105 BCE, the ruling consuls offered Rome's populus mobile (or mob) its first taste of state-sponsored "barbarian combat" between "Samnite", "Thracian" and "Gaulish" gladiator types. (temp ref.Holland) It proved immensely popular: the crowd wanted more. The state games (ludi), organised by the ruling elite and dedicated to the numen of a deity such as Jupiter, a divine or heroic ancestor (and later, during the Imperium, the Emperor), (Futrell 2006) could now compete with privately funded munera for popular support.

Peak

By the closing years of the politically and socially unstable Late Republic, nominally commemorative (rather than funereal) games offered extravagantly expensive but effective opportunities for their sponsors, and cheap, exciting entertainment for their clients, in towns and cities throughout the empire. Upwardly mobile patrons needed the support of the largely plebian populace. Votes might be had with an exceptionally spectacular show, or even its promise (Holland 2003; Welch 2007).

Ownership of gladiators or a gladiator school gave muscle and flair to Roman political arts (Holland 2003). In 65 BC, newly elected curule aedile Julius Caesar laid on a public display in Rome of three hundred and twenty pairs - in silvered armour - on the twentieth anniversary of his father's death; he had wanted more, but the nervous Senate, mindful of the recent Spartacus revolt and fearful of Caesar's burgeoning private armies, imposed a limit of 320 pairs as the maximum number of gladiators a citizen could own (Pliny, XXXIII.53).

Following the end of the Republic and the loss of real consular and Senatorial power, Augustus effectively assumed personal authority over the ludi: their provision became a formal requirement for appointment to some Imperial public offices (citation needed). The private munus was demoted. Each show required senatorial (therefore ultimately Imperial) approval, and was limited to 120 gladiators. Performance was restricted to Saturnalia, Winter solstice and the Spring celebration of Quinquatria. Throughout the Empire, the most lavish and celebrated games would now be identified with the state-sponsored Imperial cult, which furthered public recognition, respect and approval for the Emperor and his agents. (citation please)

Decline

Border incursions during the third century CE led to increasing military demands on the Imperial purse. Economic recession reduced available funds for such shows. Some emperors, such as Gordianus I, Gordianus III, and Probus continued to subsidize public performances, but privately funded shows declined. Christians saw the combats as murder, they objected most to the moral harm done to the spectators. Christians also saw the arena as a place of martyrdom and both refused to participate as spectators and sought for an end to the gladiator shows. However, Christians had no objection to the continuation of animal-on-animal fights and animal hunts (venationes).Citation needed In 325CE an edict of Constantine I briefly ended the games.

in times in which peace and peace relating to domestic affairs prevail bloody demonstrations displease us. Therefore, we order that there may be no more gladiator combats. Those who were condemned to become gladiators for their crimes are to work from now on in the mines. Thus they pay for their crimes without having to pour their blood. citation required

A game only three years later suggests this ban was not wholly effective cite required

During the 176 official holidays with games in 354CE, there were 102 theatre performances, 64 chariot races and a mere 10 days of gladiator combats. In 367CE Valentinianus I banned the sentencing of Christians to the arena (non-Christians could still be condemned to it). In 393CE, during the reighn of Theodosius Christianity was adopted as the Roman state religion; the Emperor tried to ban pagan festivals. The gladiator shows continued but in much shrunken form, with a dwindling audience. Honorius, Theodosius' son, finally decreed the end of gladiatorial contests in 399CE. The last known gladiator competition in the city of Rome occurred on January 1, 404CE. In 440CE, Bishop Salvianus published a pamphlet attacking public shows, and made no mention of gladiator games. It seems likely he would have done so if they were still happening, at least in public. (refs and citation needed throughout)

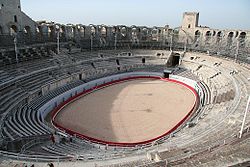

Amphitheatres

Most citizens would have witnessed gladiator combat in an arena or an amphitheatre, both found throughout the Republic and later, the Empire. The earliest arenas would have been simple, fenced areas surrounded by a temporary or permanent fence or palisade.

Early amphitheaters were wooden, flammable, and sometimes prone to collapse. The extraordinary Amphitheatre of Gaius Scribonius Curio hosted gladiator fights (Pliny the Elder 36.117). In the reign of Tiberius, a wooden amphitheater collapsed killing either twenty thousand spectators (Suetonius) or fifty thousand (Tacitus). At games in honour of Augustus' grandsons, spectators paniced in fear of imminent collapse of the amphitheatre stands. Unable to calm them, Augustus left his own seat and sat in the section most likely to fail (Suetonius XLIII).

Seating in amphitheatres was originally "disorderly and indiscriminate" until Augustus was upset at the insult to a Senator who could not find seating at a crowded games in Puteoli.

"In consequence of this the senate decreed that, whenever any public show was given anywhere, the first row of seats should be reserved for senators; and at Rome he would not allow the envoys of the free and allied nations to sit in the orchestra, since he was informed that even freedmen were sometimes appointed. He separated the soldiery from the people. He assigned special seats to the married men of the commons, to boys under age their own section and the adjoining one to their preceptors; and he decreed that no one wearing a dark cloak should sit in the middle of the house. He would not allow women to view even the gladiators except from the upper seats, though it had been the custom for men and women to sit together at such shows. Only the Vestal virgins were assigned a place to themselves, opposite the praetor's tribunal"

Suetonius Lives of the Twelve Caesars Augustus, XLIV).

The popularity of the games, their social and political usefulness refs needed - panem et circenses) and an expanding economy led to the construction of permanent, dedicated venues and the transformation of others (such as the Roman Forum) into spaces for the spectacles. The first permanent, stone amphitheater in Rome dates to around 30 BC (identity and refs needed). In AD 70 Vespasian made plans for the Amphitheatrum Flavium (The Colosseum) with seating for 50,000 spectators. It was inaugurated in 80CE.

The Stone Pine, a conifer native to the Iberian Peninsula, was often planted near provincial amphitheatres and the aromatic pinecones heated in tazze) to mask the smell of the arena. The English word arena arose from Latin harena (sand), which offered an absorbent and easily renewed surface for the arena floor.(Refs needed)

The games

The games were precisely planned by an organizer (editor) on behalf of the emperor. The combinations of animals and gladiator types were meticulously planned, such that the show would be most appealing to the audience. Gladiators would be publicly displayed in the Roman forum to large crowds one to two days prior to the actual event. Programmes containing the gladiatorial and personal history of the fighters were passed out. Banquets for the gladiators were also held the evening before the games and many attended these as well. Even the criminals (noxii) listed to fight were at times permitted to attend.

When the day of the event came, gladiator fights were preceded by animal-on-animal fights, animal hunts (venationes), and public executions of condemned criminals (damnati) during lunchtime. As it was considered bad taste to watch the executions, the upper classes would usually leave and return after lunch. The Emperor Claudius was often criticised because he usually stayed in the stadium to watch the executions. The damnati were sometimes required to fight battle recreations or in paired gladiatorial combats against each. The winner then fought a new opponent and so on until only one was left alive. Usually this "winner" was then himself put to death but he could be spared if he showed sufficient bravery. Under Nero, it became the practice to perform plays adapted from myths in which people died and assigning the role of a character who would die to a condemned man. The audience would then watch the play, and the actual killing of the condemned man in the same manner as the fictional character.[1] Before the afternoon fights began, a procession (pompa) was led into the arena containing the organizer, his servants, blacksmiths to show that the weapons were in order, servants carrying weaponry and armour, and the gladiators themselves. Next came the checking of the weapons to make sure they were real (probatio armorum) by the editor of the games. In Rome this would be by the emperor himself, or he could bestow the honour upon a guest.

The games had ticket scalpers or Ticket touts (Locarii), people who buy up seats and sell them at an inflated price. Martial in his Epigrams wrote "Hermes divitiae locariorum" or “Hermes means riches for the ticket scalpers” so scalping/touting seems to have been a common practice. The mentioned Hermes was a famous gladiator, not the deity, who was called Mercury by the Romans.

During the fights musicians played accompaniments altering their tempo to match that of the combat in the style now familiar with music in action movies[citation needed]. Typical instruments were a long straight trumpet (tubicen), a large curved instrument (Cornu) similar to an exaggerated French horn and a water organ (hydraulis). The Romans loved burlesque and pantomime and these musicians were often dressed as animals with names such as "flute playing bear" (Ursus tibicen) and "horn-blowing chicken" (Pullus cornicen), names sometimes found displayed on contemporary mosaics.[citation needed]

Like today’s athletes, gladiators did product endorsements. Particularly successful gladiators would endorse goods in the arena before commencing a fight and have their names promoting products on the Roman equivalent of billboards.[2]

During gladiatorial combat, it was preferable for gladiators not to kill each other; technically, they were slaves, but they also often had years of intensive training and therefore were quite valuable. Gladiators were instructed to inflict non-lethal wounds upon each other, and often[citation needed] lived long, rather successful lives; they were able to purchase their freedom after three years. However, accidents did happen--at times resulting in death, and gladiators who failed to display bravery in combat could be executed by order of the emperor. After fights, the bodies of the gladiators were buried in a manner depending on the status of the fighter.

As with modern sports, spectators liked to support “sides” (factiones) which they called the “great shields” (scutarii) and the “little shields” (parmularii). The “great shields” were lightly armoured defensive fighters, whereas the “little shields” were the more aggressive heavily armoured fighter types. Fighting without a shield would have been classed as a “great shield” due to fighting style[citation needed]. “Little shields” always had an advantage early in a match (as attested by the odds given by contemporary Bookmakers) but the longer the match lasted the greater the advantage for the “great shield” as his opponent tired much more quickly due to heavier armour, and also as they usually had helmets with more restricted vision. Spectators also had local rivalries. During games at Pompeii, Pompeians and spectators from Nuceria traded insults which led to stone throwing and eventually a riot broke out with many being killed or wounded. Nero was furious and banned the games at Pompeii for ten years. The story is told in graffiti on the walls of Pompeii with much boasting of their "victory" over Nuceria.

Julius Caesar in 59 BC started a daily newspaper called the Acta Diurna (daily acts) that reported gladiator news. It carried news of gladiatorial contests, games, astrological omens, notable marriages, births and deaths, public appointments, and trials and executions. The Acta's content varied over time depending on the Emperor's whims and the tastes of the public.

Life as a gladiator

Origins

Gladiators could have been either volunteer gladiators (auctoratus), prisoners of war, criminals or slaves condemned to gladiator schools (ad ludum gladiatorium). However, it is a common misconception that a majority of gladiators were slaves or criminals as, by the end of the republic, Roman law required owners to prove that a slave so condemned had comitted a serious criminal offense and up to 60% of gladiators were volunteers (auctoratii). These were either sons of prominent men perhaps looking for a radical change or men with a monetary purpose, such as Sisinnes who sought to earn money to buy a friend's freedom. For poor citizens without a trade, career options were limited to teaching for the literate, the army with a twenty year commitment or the gladiatorial schools with a chance of fame and fortune if they survived. All gladiators kept the monetary prizes that they won in the arena and Titus is on record for paying a freed slave 1,000 gold aurei to return for a single match. These men came from all different backgrounds but were soon united as they entered the training schools. By the end of the Republic, about half of the gladiators were volunteers (auctorati), who took on the status of a slave for an agreed-upon period of time, similar to the indentured servitude that was common in the late second millennium. Sometimes people were forced to fight in one off events. Caligula was known for forcing anyone he did not like to fight, including spectators who annoyed him at the games (Cassius Dio 59.10, 13-14).

One of the benefits of becoming a gladiator for slaves and criminals is that they were then allowed to have relationships with women and although they themselves could never become Roman citizens, if they gained their freedom, their marriages then were legally recognized and their children could then become citizens.[3]

Gladiator types were often patterned on the weapons and armour Rome's conqured foes. Ethnic Gauls, Thracians, and Samnites sometimes fought as that gladiator type. However, gladiators were very proud of their ethnic origins and made sure their true origin was known to the public if they fought under a title suggesting another ethnic group. Even in death they often made sure their race was inscribed on their headstone. After Judea was “pacified” there was a large increase in the number of Jewish gladiators as it was common practice under Titus and Vespasian to sentence Jewish rebels and criminals to gladiatorial schools.[4]

Left-handed gladiators were popular and a rare novelty, their fights were always advertised as a special event. As with modern-day "lefty" fencers, tennis players and other sportsman, these left-handers had a large advantage as they were trained to fight right-handers who were themselves not trained to defend against a left-hander. Mentions of left handedness on gravestones have been found. (citation or ref. required)

Research on the remains of 70 Murmillos and Retiariae gladiators found at an ancient site in Ephesus has shown that, contrary to popular belief, gladiators were probably overweight and also ate a high energy vegetarian diet consisting of mainly barley, beans and dried fruit. Fabian Kanz of the Austrian Archaeological Institute said he believed gladiators "cultivated layers of fat to protect their vital organs from the cutting blows of their opponents". Gladiators were sometimes known as hordearii, which means "eaters of barley". Although considered an inferior grain to wheat (a punishment for Legionaries was to replace their wheat ration with barley), gladiators probably preferred it as Romans believed that barley contributed to strength and covered the arteries with a layer of fat which helped to reduce bleeding. Other findings from the research indicate gladiators fought barefoot in sand.[5]

Training

Estimations are that there were more than 100 gladiator schools (ludi) throughout the empire. Two of the more famous are the school in Capua where Spartacus was trained and the school in Pompeii that was buried in the 79 CE eruption of Vesuvius. Following the Spartacus Revolt, The Senate restricted the siting and strength of the gladiator schools.)(ref needed). One of the largest schools was based in Ravenna. There were four schools in Rome: Ludus Magnus (the most important), Ludus Dacicus, Ludus Gallicus, and Ludus Matutinus (school for gladiators dealing with animals). The schools had barracks for the gladiators with small cells and a large training ground. The most impressive had seating for spectators to watch the men train and some even had boxes for the emperor. (citation needed)

Prospective gladiators (novicius) upon entering a gladiator school swore an oath (sacramentum) giving their lives to the gods of the underworld and vowing to accept, without protest, humiliation by any means. Volunteers also signed a contract (auctoramentum) with a gladiator manager (lanista) stating how often they were to perform, which weapons they would use, and how much they would earn. Prospectives also went under a physical examination by a doctor to determine if they were both physically capable of the rigorous training and aesthetically pleasing. Once accepted the novicius usually had his debts forgiven and was given a sign up fee. For as long as he was a gladiator he was well fed and received high quality medical care. Overall, gladiators were united as members of a familia gladiatoria and became second to the prestige of the school. They also joined unions (collegia) formed to ensure proper burials for fallen members and compensation for their families.(citation needed)

As a rule gladiators, slaves and criminals had tattoos (stigma) applied as an identifying mark on the face, legs and hands (legionnaires were also tattooed but only on their hands[citation needed] ). This practice continued until the emperor Constantine banned them on the face by decree in AD 325.[6]

Training was under teachers called “Doctores” and involved the learning of a series of “numbers”, which were broken down into various phases much as a play is a series of acts broken down into scenes. Sometimes fans complained that a gladiator fought too “mechanically” when he followed the “numbers” too closely. Gladiators would even be taught how to die correctly. Each type of gladiator had its own teacher; doctore secutorum, doctore thracicum, etc. Although gladiators in times of need helped train legionaries, they were not usually good soldiers themselves as a result of this choreographed style of training. Within a training-school there was a competitive hierarchy of grades (paloi) through which individuals were promoted. They trained using two meter poles (palus) buried in the ground. The levels were named for the training pole and were primus palus, secundus palus, and so on. It was also rare for a novicius to train in more than one gladiatorial style. Once a gladiator had finished training but had not yet fought in an arena he was called a “Tiro”.(citations needed)

Typical combat

Forthcoming shows were often advertised by a program (libellus), painted on the city walls, sometimes including depictions of featured fighters. Sometimes the results of individual combats were added to these names (or images) after the matches: "v" stood for "vicit" (he won) and "p" for "periit" (he died). An "m" meant "missus" (he lost but was spared). Games were often commemorated with a representation of the fight and a brief inscription; for example "Astyanax defeated Kalendio"). Portrayals (or names) of defeated and dead gladiators were marked with a circle, usually but not invariably struck through by a diagonal line: Ø, usually placed close to or over the head (or name).

An average game had between ten and thirteen pairs (Ordinarii) of gladiators, with a single bout lasting around ten to fifteen minutes. They were usually of differing types. However, sponsor or audience could request other combinations like several gladiators fighting together (Catervarii) or specific gladiators against each other. Sometimes a lanista had to rely on substitutes (supposititii) if the requested gladiator was already dead or incapacitated. The Emperor could have his own gladiators (Fiscales). The largest contest of gladiators ever given was by the emperor Trajan in Dacia as part of a victory celebration in 107 CE and included 5,000 pairs of fighters.

Some matches were advertised as “sine missione” (without release) meaning “to the death”. The referees allowed these fights to continue as long as it took to get a result. Although already a rare event, Augustus outlawed “sine missiones” due to the expense of compensating their owners (Lanistas) but they were later reintroduced. If a gladiator was killed it was normal practice for the games sponsor to pay compensation to the Lanista of up to 100 times the gladiator's value. For the death of a popular gladiator this could be very expensive as their value was comparable to that of the sporting elite of today.

When one gladiator was wounded the spectators would yell out one of several traditional cheers such as "habet, hoc habet” (he’s had it) or "habet, peractum est” (he's had it, it's all over), the referee would then end the fight by separating the combatants with his staff. A gladiator could also acknowledge defeat by raising a finger (ad digitum), The referee would then step in, stopping the combat, and refer the decision of the defeated gladiator’s fate to the games sponsor (munerarius) who would decide whether he should live or die after taking the audiences wishes into account or considering how well he had fought.

Fights were generally not to the death during the Republic, but gladiators were still killed or maimed accidentally. Claudius was infamous for rarely sparing the life of a defeated Retiarius. He liked to watch his face as he died, as the Retiarius was the only gladiator that never wore a helmet. Suetonius recounts a combat where the death of an opponent was called a murder. "Once a band of five retiarii in tunics (retiarius tunicatus), matched against the same number of secutores, yielded without a struggle; but when their death was ordered, one of them caught up his trident and slew all the victors. Caligula bewailed this in a public proclamation as a most cruel murder." (Lives of the Twelve Caesars XXX.3)

The figure of a referee is frequently depicted on mosaics as standing in the background, sometimes accompanied by an assistant and carrying a staff with which to hold back a gladiator after his opponent signified submission. This implies contests were fought with fixed rules. We know from Roman mosaics, and from surviving skeletons that gladiators primarily aimed for the head and the major arteries under the arm and behind the knee. [citation needed]

Professional gladiators received a fee for each combat. Victors received from the editor a palm branch and an award, usually in gold (in the form of small artefacts or money). They might also receive money collected from an appreciative crowd, and a laurel crown for an outstanding performance. The victor then ran (if able to) around the perimeter of the amphitheatre, waving the palm. Gladiators were allowed to keep any money or gold they received as a prize. The ultimate prize awarded to gladiators was a permanent discharge from the obligation to fight, symbolised by the gift of a wooden sword (rudis) by the editor. Martial (Spect. 27) describes a famous match between two gladiators, named Priscus and Verus, who fought so evenly and bravely for so long that when they both acknowledged defeat at the same instant, the emperor Titus awarded victory and a rudis to each. Generally, gladiators (including those sentenced as criminals to the arena) could earn their freedom if they survived three to five years of combat;no rules appear to have determined what was required apart from precedent and custom. If a gladiator won five fights, or especially distinguished himself, he might receive the rudis. An exceptional and famous Secutor nicknamed Flamma was awarded the rudis four times but chose to remain a gladiator, and survived until his 34th fight. Flamma's gravestone in Sicily is particularly informative as it includes his record: Flamma, secutor, lived 30 years, fought 34 times, won 21 times, fought to a draw 9 times, defeated 4 times, a Syrian by nationality. Delicatus made this for his deserving comrade-in-arms.[7]

Martial describes the fate of a losing gladiator, once the crowd had given the signal for him to be killed. With one knee on the ground, the loser grasped the thigh of the victor, who, while holding the helmet or head of his opponent, plunged his sword into his neck or cut his throat depending on his weapon. Gladiator remains found at Ephesus confirmed this a a common method. Marks on the bones of several suggested that in each case a sword was thrust into the base of the throat in a downward direction, which would have pierced the heart. To die well, a gladiator should never ask for mercy, nor cry out. (Cicero citation required) Recent research suggests that gladiators fighting styles were formal and disciplined, tending not to inflict the random mutilations expected from battlefield violence. A living but mortally wounded the gladiator whom the crowd had spared was taken from the arena to be executed "humanely" with a hammer on the forehead, in private.[8]

After the death of a gladiator in combat, two attendants impersonating Charon (ferryman of Hades) and Mercury (messenger to the gods) would approach the body. Charon would strike the body with a mallet and Hermes would then prod the body with a hot poker disguised as a wand to see whether the gladiator was really dead or not. In the larger games, the corpse was then placed on a "couch of Libitina" by bearers (libitinarii), and taken from the arena through the Libitinarian Gate. Victors left via the Porta Triumphalis, and losers via the Porta Sanavivaria). In lesser games the libitinarii often used hooks to drag the body. Attendants then spread a fresh layer of sand to soak up the blood. Libitina was the goddess of funerals. After stripping the armour, the gladiator's body was then taken to a nearby morgue (spoliarium) where by custom, as final proof the fight was not "fixed", officials slit the man's throat to ensure that he was truly dead.[9] (need up to date scholarly refs)

Life expectancy of a gladiator

Gladiators rarely lived past age 30 unless they were particularly outstanding and accomplished victors, but at a time when around 50 percent of Roman citizens died, from all causes, before age 25,[10] this indicates that gladiators in fact tended to live longer than the general populace which is attributed to the extra care they received. Reasonable estimates show that they fought on average two to three times yearly, but there are some exceptions such as some men fighting all nine days during one of Trajan's shows.[citation needed]

French historian George Villes evaluated 100 fights from the 1st century CE, involving 200 gladiators, and found that 19 gladiators had lost their lives.[citation needed] His evaluations of gladiator gravestones indicates that the average age at time of death was around 27 years. However, historian Marcus Junkelmann points out that only the most successful gladiators were usually given a headstone and that the majority of the gladiators who died were at the beginning of their career and thus not included in this average. According to Junkelmann the majority died between 18 and 25 years of age.[citation needed]

Slave revolts

Rome had to fight three Servile Wars, the last being against one of the most famous gladiators — Spartacus who became the leader of a group of escaped gladiators and slaves. His revolt, which began in 73 BC, was crushed by Marcus Crassus two years later in 71 BC. After this, gladiators were deported from Rome and other cities during times of social disturbances, for fear that they might organize and rebel again. As well, armouries within the schools were closely guarded and gladiators who were potential threats were chained.

Gladiators in Roman Life

Legal and social status

Most gladiators were slaves, rather than free. A citizen who became a "professional" gladiator was socially disgraced - their legal designation, infamia, involved loss of certain public rights tantamount to selling oneself into indentured servitude[11]. On the other hand, successful gladiators could rise to popular celebrity status, with all its rewards. Until the Larinum decree under Tiberius blocked the possibility, it was possible for those of senatorial and equestrian degree to join gladiator schools and fight in the arena. Those of lesser degree (plebs and freedmen), could become volunteer gladiators (auctorati),independent of a school or indenture, with no significant loss of face, and no change in legal status c[12]: for those of higher status, loss of face could be complete and irrecoverable. (cite Gracchi, with cautionary note).(passage needs some revison)

Being a Lanista was a very lucrative business,[13]. Socially, a professional Lanista ranked lower than a prostitute; but an amateur Lanista, of good family and independent means, was not stigmatised at all.(citation needed)

Ethics, Morals and Sentiment

Gaius Marius found it quite acceptable for gladiators train the legionaries in single combat. For some Romans, the popularity of the gladiator show threatened the moral fabric of Rome: there were lessons to be drawn from the past -

...it was their [the Campanians] custom to enliven their banquets with bloodshed and to combine with their feasting the horrid sight of armed men fighting; often the combatants fell dead above the very cups of the revelers, and the tables were stained with streams of blood. Thus demoralised was Capua. Silius Italicus (11.51) on the ancient Capuans. (in Lutrell, 2006)

Cicero was torn between aristocratic contempt for the unrestrained blood-lust of the mob and admiration for the courage gladiators:

Even when they have been felled,let alone when they are standing and fighting, they never disgrace themselves. And suppose a gladiator has been brought to the ground, when do you ever see one twist his neck away after he has been ordered to extend it for the death blow? (Cicero: Tusculan disputations,2.41)

The lavishness of the games was offensive to some. In 46BCE Caesar memorialised his daughter Julia, eight years after her death, in ceremonies that included gladiatorial contests. The celebration was described by some contemporaries as excessive, in lost human lives and in cash better spent on needy veterans(Dio, XLIII.24).

Seneca and Pliny the Younger found the mob's blood-lust distasteful(quote and cite). Tertullian disapproved, partly because he felt such practices a blasphemous imitation of martyrdom, partly because they inflamed the passions (fuller context and cites required).

However, at their peak, the gladiator shows had widespread (and to their chroniclers, sometimes outrageous) support among all classes. Cassius Dio (62.17.3), writes of a festival Nero held in honour of his mother: “Many ladies of distinction, however, and senators, disgraced themselves by appearing in the amphitheatre”. Tacitus (15.32) records that:

There was another exhibition that was at once most disgraceful and most shocking, when men and women not only of the equestrian but even of the senatorial order appeared as performers in the orchestra, in the Circus, and in the hunting-theatre, like those who are held in lowest esteem; they drove horses, killed wild beasts and fought as gladiators, some willingly and some sore against their will

Emperor Marcus Aurelius found little to admire in gladiator, but repected the stoicism of the fighters; he saw the gladiators as privileged athletes and took extraordinary measures to prevent bloodshed and death (Cassius Dio 71.29.4), such as the use of blunted weapons.[14]

Gladiators often developed large followings of women, who apparently saw them as sexual objects despite it being socially unacceptable for citizen women to have sexual contact with them:

What was the youthful charm that so fired Eppia? What hooked her? What did she see in him to make her put up with being called "the gladiator's moll"? Her poppet, her Sergius, was no chicken, with a dud arm that prompted hope of early retirement. Besides his face looked a proper mess, helmet-scarred, a great wart on his nose, an unpleasant discharge always trickling from one eye. But he was a gladiator. That word makes the whole breed seem handsome, and made her prefer him to her children and country, her sister, her husband. Steel is what they fall in love with. (Juvenal: Satires: 6.102 ff. Translated by P. Green).

A wall graffito in Pompeii describes the Thracian gladiator Celadus as "suspirum et decus puellarum", (the sigh and glory of the girls). Faustina the Younger, mother of the emperor Commodus, was said to have conceived Commodus with a gladiator, but Commodus likely invented this story himself. Despite or because of the prohibition many rich women sought intimate contact with gladiators and there are several instances of historians mentioning Senators wives running off to live with gladiators. The ancient celebrity and the festivity before the fights gave the women an opportunity to meet them.(citations definitely required)

Gladiators in Roman Art and culture

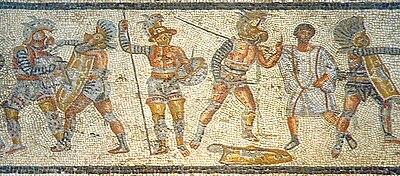

Gladiators were considered an acceptable subject in art, throughout the Republic and Empire (ref: link to 2nd cent BCE Italian Agora in Delos). The Gladiator Mosaic(date) shows several gladiator types,and the Bignor Roman villa mosaic show Cupids as gladiators. Souvenir bowls were also produced depicting named gladiators in combat. and more expensive articles for the wealthy (see lanx, silver, mosaic)

Pliny the Elder gives vivid examples of the popularity of gladiator portraiture in Antium and an artistic treat laid on by an aristocrat for the solidly plebian citizens of the Roman Aventine:

When a freedman of Nero was giving a gladiatorial show at Antium, the public porticoes were covered with paintings, so was are told, containing life-like portraits of all the gladiators and assistants. This portraiture of gladiators has been the highest interest in art for many centuries now, but it was Gaius Terentius who began the practise of having pictures made of gladiatorial shows and exhibited in public; in honour of his grandfather who had adopted him he provided thirty pairs of Gladiators in the Forum for three consecutive days, and exhibited a picture of the matches in the Grove of Diana. (Pliny, Natural History 30.32)

(subset: in theatre: in novels, poems and epigrams)

Retiarius Tunicatus

Even lower on the social scale were gladiators considered effeminate. They appear to have fought primarily as Retiarii or more specifically Retiarius Tunicatus, named for the tunic they wore to differentiate them from normal Retiarii who fought bare chested. Although mentioned by Juvenal, Seneca and Suetonius very little detail is given. They are referred to as training in an “indecent part of the gladiator's school” and fighting in a “disgraceful type of armament”. Juvenal mentions the trainers practice of keeping separate "from their fellow retiarii the wearers of the ill-famed tunic”.[15]

It was thought by their contemporaries that they willingly became Retiarii to exhibit both their vanity and contempt for disgrace as their faces were not hidden by a helmet as was the case with other gladiator types.

"In this way they incurred death instead of disfranchisement; for they fought just as much as ever, especially since their contests were eagerly witnessed, so that even Augustus used to watch them in company with the praetors who superintended the contests" (Cassius Dio, LVI.25.7).

The only named example of this class of gladiator was Gracchus, an aristocrat and descendant of the Gracchi who was infamous for his marriage (as a bride) to a male horn player. It is recorded by Cassius that he voluntarily fought, not only as a Retiarius Tunicatus, but wore a conical hat adorned with gold lace and ribbons during the combat (Gracchus was also chief of the priests of Mars (Salii) for whom this hat was normal attire).

Female gladiators

Female gladiators[16] also existed. Women also often fought as Venatores but these are not considered true gladiators.[17]

The Emperor Domitian liked to stage torchlit fights between dwarves and women, according to Suetonius in The Twelve Caesars. From depictions it appears they fought bare-chested and rarely wore helmets no matter what type of gladiator they fought as.

Women apparently fought at night, and this being the time that the games main events were held indicates the possible importance or rarity of female gladiators. Most modern scholars consider female gladiators a novelty act due to the sparse writings about them but those ancient historians that do mention them do so “casually” which suggests that female gladiators were "more widespread than direct evidence might otherwise indicate".[18] The author of an inscription found in Pompeii boasts of being the first editor to bring female gladiators to the town.

Dio Cassius (62.3.1) mentions that not only women but children fought in a gladiatorial event that Nero sponsored in 66 AD. It is known the emperor Nero also forced the wives of some Roman senators into amphitheatres, presumably to fight.

A 1st or 2nd century Marble relief from Halicarnassus suggests that some women fought in heavy armour. Both women are depicted as provocatrices in combat. The inscription names them as “Amazon” and “Achillia” and mentions that both received an honourable discharge (missio) from the arena despite fighting each other (both deemed to have won).

Mark Vesley, a Roman social historian speculates that as gladiatorial schools were not fit places for women, they may have studied under private tutors in the collegia iuvenum. These schools were for training high ranking males over the age of 14 in martial arts but Vesley found three references to women training there as well including one who died..."To the divine shades of Valeria Iucunda, who belonged to the body of the iuvenes. She lived 17 years, 9 months".

A female Roman skeleton unearthed in Southwark, London in 2001 was identified as a female gladiator, but this was on the basis that although wealthy she was buried as an outcast outside the main cemetery, had pottery lamps of Anubis (i.e., Mercury, the gladiatorial master of ceremonies), a lamp with a depiction of a fallen gladiator engraved and bowls containing burnt pinecones from a Stone Pine placed in the grave. The only Stone Pines in Britain at the time were those planted around the London amphitheatre as the pinecones of this particular species were traditionally burnt during games. Most experts believe the identification to be erroneous but the Museum of London states it is "70 percent probable" that the Great Dover Street Woman was a gladiator. Hedley Swain, head of early history at the Museum states: "No single piece of evidence says that she is a gladiator. Instead, there’s simply a group of circumstantial evidence that makes it an intriguing idea". She is now on display at the end of the Roman London section of the Museum of London. This gladiator was the subject of a program on the UK's Channel 4.[19]

Emperors as gladiators

Caligula, Titus, Hadrian, Lucius Verus, Caracalla, Geta and Didius Julianus were all said to have performed in the arena.[20] It is uncertain if these performances were one-time-only or repeated appearances and there is question regarding the risk as the emperors chose their opponents and no one was likely to injure an emperor. Commodus, however, is known for his passion for public performance and is remembered for his participation in gladiatorial shows as a Secutor fighting under the title of "Hercules". He is also known for his voluntary role as a bestiarii. According to Gibbon, Commodus once killed 100 lions in a single day.[21] Later, he decapitated a running ostrich with a specially designed dart[22] and afterwards carried the bleeding head of the dead bird and his sword over to the section where the Senators sat and gesticulated as though they were next.[23] On another occasion, Commodus killed 3 elephants on the floor of the arena by himself.[24] He is often depicted this way in art, including a statue outside the Colosseum that he had had boastfully incribed "Champion of secutores; only left-handed fighter to conquer twelve times (as I recall the number) one thousand men". Commodus also dedicated an inscription that claimed 620 victories as a gladiator. He also raced chariots, chased animals in the arena, hunted wild animals from the stands and was so impressive that it is said that he rarely needed a second spear to kill his prey.[25] According to Pliny, Emperor Claudius fought a whale trapped in the harbor in front of a group of spectators.[26]

Misconceptions

It is known that the audience (or sponsor or emperor) pointed their thumbs a certain way if they wanted the loser to be killed (called a pollice verso, literally "with turned thumb"), but it is not clear which way they actually pointed. A thumbs up (called pollux infestus) was an insult to Romans so is unlikely to have meant sparing a life. The clear "thumbs up" and "thumbs down" image is not a product of historical sources, but of Hollywood and epic films such as Quo Vadis. It is thought they may have raised their fist with the thumb inside it (pollice compresso, literally "with compressed thumbs") if they wanted the loser to live. One popular belief is that the "thumbs down" meant lower your weapon, and let the loser live and a thumbs up sign pointed towards the throat or chest, signaled the gladiator to stab him there. Some scholars believe that a hand movement was involved as the notion of "turning" does not seem to fit the action of merely extending a thumb. One of the few sources to allude to the use of the "thumbs up" and "thumbs down" gestures in the Roman arena comes from Satire III of Juvenal (3.34-37)[27] and seems to indicate that, contrary to modern usage, the thumbs down signified that the losing gladiator was to be spared and that the thumbs up meant he was to be killed. A carved relief of a gladiator being spared also exists that shows the hand "sign" as a thumb laid flat along the hand (pressed?) with two fingers extended and two clenched. This has led some to believe those who wanted the gladiator killed waved their thumbs in any direction they wanted, and those who wanted him spared kept their thumbs pressed against their hands.

Possibly the most portrayed misconception is the persecution and "throwing to the lions" of Christians by Emperors and in particular Nero. According to the writings of Hippolyte Delehaye the first mention of this particular form of persecution was in the 16th century to justify pillaging building material from the Colosseum to rebuild St Peters. There is actually no record of any Christian being put to death in the Colliseum for being a Christian. Following the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD, Emperor Nero executed many "arsonists" but none were executed during games.[28] A later writer composed a "martyrology" of the names of Pagan men and women who were victims of Nero and it is believed later Christian writers borrowed this account, attributing Christianity to all the victims.[29] Many scholars believe that the first real persecution of Christians was by Constantine I who executed more Christians for being Christian (because their interpretation of the Bible did not agree with his) than all the preceding Roman Emperors combined.[30] (dubious non-scholarly POV)

The now famous gladiatorial salute “Ave Caesar, morituri te salutant” or “Hail Caesar, they who are about to die salute you” is another product of movies. This salute was only mentioned by Suetonius (Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Claudius, XXI, 1214) as happening once, spoken by condemned men (damnati) to Claudius at a naumachia (a staged naval battle) and they used the word “imperator” (Emperor) not Caesar. Tacitus also wrote of this event:

“although they were criminals, they fought with the spirit of brave men. Their (the survivors') reward was exemption from the penalty of wholesale execution”.

Another myth perpetuated by movies is combat between gladiators who did not know one another. As a rule gladiators only fought others from within their own school or troupe (ad ludum gladiatorium) although sometimes specific gladiators would be requested to fight one from another troupe (Postulaticii) as a special event.

The cutting up of the bodies to feed the animals is another common misconception and is mentioned only by Suetonius as an extraordinary and unheard of action that Caligula ordered to be done only once. The bodies of noxii and damnati were either buried or thrown into rivers, this being the traditional Roman disposal method for the bodies of executed criminals while other gladiators were often buried with honours by their "union" (collegia) or friends. Animal carcasses were either disposed of or distributed to the poor for sustenance.

Although ancient Romans did not normally wear hats (went heads bare capite aperto) and this is seen in today's movie depictions of games, it was actually customary for free men to wear white woolen conical hats when attending games and festivals[31]. The hats were a symbol of liberty.

Gladiators in films and television

Gladiators feature frequently in many epic films and television series set in this period. These include films such as four versions of Ben-Hur, Spartacus (1960), Gladiator (2000) and Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954), Quo Vadis, as well as the television series A.D. (1985) (which features a female gladiator), and Rome.

See also

References

- ^ K. M. Coleman, The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 80, 1990 (1990), pp. 44-73]

- ^ Not Such a Wonderful Life: A Look at History in Gladiator IGN movies February 10, 2000

- ^ The Gladiator Brooklyn College Classics Department

- ^ Roman Civilization History 206 Bates College

- ^ Roman gladiators were fat vegetarians, ABC Science April 5 2004.

- ^ Greek and Roman Tattoos

- ^ Flamma tombstone

- ^ "Head injuries of Roman gladiators", Forensic Science International, Volume 160, Issue 2–3, Pages 207–216 F. Kanz, K. Grossschmidt

- ^ Archaeology: Vox Populi Discover Magazine July 2006

- ^ Roman Life Expectancy University of Texas

- ^ Roman Law - Infamia Smiths Dictionary 1875 pp634‑636

- ^ http://www.personal.kent.edu/~bkharvey/roman/texts/sclaurin.htm

- ^ Cicero wrote that his friend Atticus might recover his entire investment in a gladiator troupe after two performances.

- ^ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/72*.html#p51

- ^ The Retiarius Tunicatus of Suetonius, Juvenal, and Petronius" (1989) by Steven M. Cerutti and L. Richardson, Jr., The American Journal of Philology, 110, P589-594

- ^ In Latin gladiator has no feminine form. However, while gladiator is preferred, "gladiatrix" is acceptable to historians.

- ^ "Female Gladiators of the Ancient Roman World", Journal of Combative Sport, July 2003.

- ^ Zoll, A. (2002). Gladiatrix: The True Story of History’s Unknown Woman Warrior. New York: Berkley Publishing Group, p. 27.

- ^ Gladiator Girl Channel 4 May 14,2001

- ^ Barton, Carlin (1995). The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster. Page 66. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691010919.

- ^ Gibbon pg 106 "disgorged at once a hundred lions; a hundred darts"

- ^ Gibbon, Edward The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire': Volume I' Everyman's Library (Knopf) New York. 1910. pg 106 "with arrows whose point was shaped in the form of a cresent"

- ^ Fox, Robin The Classical World: An Epic History from Homer to Hadrian Basic Books. 2006 pg 446 "brandishing a sword in one hand and bloodied neck...He gesticulated at the Senate."

- ^ Scullard, H.H The Elephant in the Greek and Roman World Thames and Hudson. 1974 pg 252

- ^ The Gladiator Emperor UNRV History

- ^ Fox, Robin The Classical World: An Epic History from Homer to Hadrian Basic Books. 2006 pg 576

- ^ Juvenal III

- ^ Tacitus annals-xv-44

- ^ Legends of Saints and Martyrs By Joseph McCabe 2007 ISBN 1432627139

- ^ Crimes of Christianity By G. W. Foote 1990 ISBN 0916157628

- ^ Martial xi.7. xiv.1 Suetonius Ner.57. Seneca Epist.18

Further reading

- Gladiator: Film and History, edited by Martin M. Winkler. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2004 (hardcover, ISBN 1-4051-1043-0; paperback, ISBN 1-4051-1042-2).

- James Grout: Gladiators, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- Violence and the Romans: The Arena Spectacles

- The Revolt of Spartacus A narrative essay.

- Daniel P Mannix: Those About To Die, Ballantine Books, New York 1958

- Michael Grant: Gladiators, Penguin Books, London 1967, reprinted 2000, ISBN 0-14-029934-3

- Roland Auguet: Cruelty and Civilization: The Roman Games, Paris 1970; English reprint Routledge 1994

- IMDB- movie titles containg 'Gladiator' etc.; click also on keywords

- Thomas Wiedemann: Emperors and Gladiators, Routledge 1992

- Fik Meijer: The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport, Thomas Dunne Books 2003; reprinted by St. Martin's Griffin 2007. ISBN-13 978-0-312-36402-1; ISBN-10 0-312-36402-4.

- Eckart Köhne and Cornelia Ewigleben (editors); Gladiators and Caesars; British Museum Press, London, 2000; ISBN 0-5202279-80-1

- Gladiators: Heroes of the Roman Amphitheatre

- The Roman Gladiator

- History of the Roman Empire. Culture. Roman Gladiators:

- Gladiators Archaeological Institute of America Index of articles related to Gladiators.