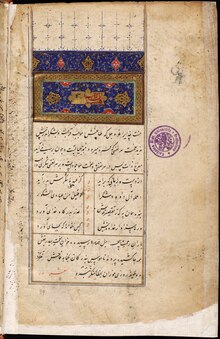

Gulistan (book)

The Gulistan (Persian: گلستان Golestȃn[1] "The Rose Garden") is a landmark of Persian literature, perhaps its single most influential work of prose.[1] Written in 1258 CE, it is one of two major works of the Persian poet Sa'di, considered one of the greatest medieval Persian poets. It is also one of his most popular books, and has proved deeply influential in the West as well as the East.[2] The Gulistan is a collection of poems and stories, just as a rose-garden is a collection of roses. It is widely quoted as a source of wisdom. The well-known aphorism still frequently repeated in the western world, about being sad because one has no shoes until one meets the man who has no feet "whereupon I thanked Providence for its bounty to myself" is from the Gulistan.[3]

The minimalist plots of the Gulistan's stories are expressed with precise language and psychological insight, creating a "poetry of ideas" with the concision of mathematical formulas.[1] The book explores virtually every major issue faced by humankind, with both an optimistic and a subtly satirical tone.[4] There is much advice for rulers, in this way coming within the mirror for princes genre. But as Eastwick comments in his introduction to the work,[5] there is a common saying in Persian, "Each word of Sa'di has seventy-two meanings", and the stories, alongside their entertainment value and practical and moral dimension, frequently focus on the conduct of dervishes and are said to contain sufi teachings.

Reasons for composition

In his introduction Sa'di describes how a friend persuaded him to go out to a garden on 21 April 1258. There the friend gathered up flowers to take back to town. Sa'di remarked on how quickly the flowers would die, and proposed a flower garden that would last much longer:

- Of what use will be a dish of roses to thee?

- Take a leaf from my rose-garden.

- A flower endures but five or six days

- But this rose-garden is always delightful.

Sa'di continues, "On the same day I happened to write two chapters, namely on polite society and the rules of conversation, in a style acceptable to orators and instructive to letter-writers.".[6] In finishing the book, Sa'di writes that, though his speech is entertaining and amusing, "it is not hidden from the enlightened minds of sahibdils (possessors of heart), who are primarily addressed here, that pearls of healing counsel have been drawn onto strings of expression, and the bitter medicine of advice has been mixed with the honey of wit".[7]

Structure

After the introduction, the Gulistan is divided into eight chapters, each consisting of a number of stories and poetry:[8]

- 1. The Manners of Kings

- 2. On the Morals of Dervishes

- 3. On the Excellence of Contentment

- 4. On the Advantages of Silence

- 5. On Love and Youth

- 6. On Weakness and Old Age

- 7. On the Effects of Education

- 8. On Rules for Conduct in Life

[9] Some stories are very brief. They are accompanied by short verses sometimes representing the words of the protagonists, sometimes representing the author's perspective and sometimes, as in the following case, not clearly attributed:

Chapter 1, story 34

One of the sons of Harunu'r-rashid came to his father in a passion, saying, "Such an officer's son has insulted me, by speaking abusively of my mother." Harun said to his nobles, "What should be the punishment of such a person?" One gave his voice for death, and another for the excision of his tongue, and another for the confiscation of his goods and banishment. Harun said, "O my son! the generous part would be to pardon him, and if thou canst not, then do thou abuse his mother, but not so as to exceed the just limits of retaliation, for in that case we should become the aggressors."

- They that with raging elephants make war

- Are not, so deem the wise, the truly brave;

- But in real verity, the valiant are

- Those who, when angered, are not passion's slave.

Since there is little biographical information about Sa'di outside of his writings, his short, apparently autobiographical tales, such as the following have been used by commentators to build up an account of his life.

Chapter 2, story 7

I remember that, in the time of my childhood, I was devout, and in the habit of keeping vigils, and eager to practise mortification and austerities. One night I sate up in attendance on my father, and did not close my eyes the whole night, and held the precious qur'an in my lap while the people around me slept. I said to my father, "Not one of these lifts up his head to perform a prayer. They are so profoundly asleep that you would say they were dead." He replied, "Life of thy father! it were better if thou, too, wert asleep; rather than thou shouldst be backbiting people."

- Naught but themselves can vain pretenders mark,

- For conceit's curtain intercepts their view.

- Did God illume that which in them is dark,

- Naught than themselves would wear a darker hue.[10]

Most of the tales within the Gulistan are longer, some running on for a number of pages. In one of the longest, in Chapter 3, Sa'di explores aspects of undertaking a journey for which one is ill-equipped:

Chapter 3, story 28

An athlete, down on his luck at home, tells his father how he believes he should set off on his travels, quoting the words:

- 'As long as thou walkest about the shop or the house

- Thou wilt never become a man, O raw fellow.

- Go and travel in the world

- Before that day when thou goest from the world.'

His father warns him that his physical strength alone will not be sufficient to ensure the success of his travels, describing five kinds of men who can profit from travel: the rich merchant, the eloquent scholar, the beautiful person, the sweet singer and the artisan. The son nevertheless sets off and, arriving penniless at a broad river, tries to get a crossing on a ferry by using physical force. He gets aboard, but is left stranded on a pillar in the middle of the river. This is the first of a series of misfortunes that he is subjected to, and it is only the charity of a wealthy man that finally delivers him, allowing him to return home safe, though not much humbled by his tribulations. The story ends with the father warning him that if he tries it again he may not escape so luckily:

- 'The hunter does not catch every time a jackal.

- It may happen that some day a tiger devours him.'

Chapter 5, story 5

In the fifth chapter of The Gulistan of Saadi, on Love and Youth, Saadi includes explicit moral and sociological points about the real life of people from his time period (1203-1291). One story about a schoolboy sheds light on the issues of sexual abuse and pedophilia, problems that have plagued all cultures. This story by Saadi, like so much of his work, conveys meaning on many levels and broadly on many topics. In this story, Saadi communicates the importance of teachers educating the “whole child”—cognitively, morally, emotionally, socially, and ethically. Even though adults and teachers have been accorded great status and respect in Iranian culture and history, in Saadi’s story, he shows that a young boy has great wisdom in understanding his educational needs.

- A schoolboy was so perfectly beautiful and sweet-voiced that the teacher, in accordance with human nature, conceived such an affection towards him that he often recited the following verses:

- I am not so little occupied with you, O heavenly face,

- That remembrance of myself occurs to my mind.

- From your sight I am unable to withdraw my eyes

- Although when I am opposite I may see that an arrow comes.

- Once the boy said to him: “As you strive to direct my studies, direct also my behavior. If you perceive anything reprovable in my conduct, although it may seem approvable to me, inform me thereof that I may endeavor to change it.” He replied: “O boy, make that request to someone else because the eyes with which I look upon you behold nothing but virtues.”

- The ill-wishing eye, be it torn out

- Sees only defects in his virtue.

- But if you possess one virtue and seventy faults

- A friend sees nothing except that virtue.[12]

Influence

Sa'di's Gulistan is said to be one of the most widely read books ever produced.[7] From the time of its composition to the present day it has been admired for its "inimitable simplicity",[1] seen as the essence of simple elegant Persian prose. Persian for a long time was the language of literature from Bengal to Constantinople, and the Gulistan was known and studied in much of Asia. In Persian-speaking countries today, proverbs and aphorisms from the Gulistan appear in every kind of literature and continue to be current in conversation, much as Shakespeare is in English.[1][13] As Sir John Malcolm wrote in his Sketches of Persia in 1828, the stories and maxims of Sa'di were "known to all, from the king to the peasant".[14]

In Europe

The Gulistan has been significant in the influence of Persian literature on Western culture. La Fontaine based his "Le songe d'un habitant du Mogol"[15] on a story from Gulistan chapter 2 story 16: A certain pious man in a dream beheld a king in paradise and a devotee in hell. He inquired, "What is the reason of the exaltation of the one, and the cause of the degradation of the other? for I had imagined just the reverse." They said, "That king is now in paradise owing to his friendship for darweshes, and this recluse is in hell through frequenting the presence of kings."

- Of what avail is frock, or rosary,

- Or clouted garment? Keep thyself but free

- From evil deeds, it will not need for thee

- To wear the cap of felt: a darwesh be

- In heart, and wear the cap of Tartary.[5]

Voltaire was familiar with works of Sa'di, and wrote the preface of Zadig in his name. He mentions a French translation of the Gulistan, and himself translated a score of verses, either from the original or from some Latin or Dutch translation.[16]

Sir William Jones advised students of Persian to pick an easy chapter of the Gulistan to translate as their first exercise in the language. Thus, selections of the book became the primer for officials of British India at Fort William College and at Haileybury College in England.[1]

In the United States Ralph Waldo Emerson who addressed a poem of his own to Sa'di, provided the preface for Gladwin's translation, writing, "Saadi exhibits perpetual variety of situation and incident ... he finds room on his narrow canvas for the extremes of lot, the play of motives, the rule of destiny, the lessons of morals, and the portraits of great men. He has furnished the originals of a multitude of tales and proverbs which are current in our mouths, and attributed by us to recent writers." Henry David Thoreau quoted from the book in A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers and in his remarks on philanthropy in Walden.[1]

Translations

Saʿdi was first introduced to the West in a partial French translation by André du Ryer (1634). Friedrich Ochsenbach based a German translation (1636) on this. Georgius Gentius produced a Latin version accompanied by the Persian text in 1651.[17] Adam Olearius made the first direct German translation.[1]

The Gulistan has been translated into many languages. It has been translated into English a number of times: Stephen Sullivan (London, 1774, selections), James Dumoulin (Calcutta, 1807), Francis Gladwin (Calcutta, 1808, preface by Ralph Waldo Emerson),[18] James Ross (London, 1823),[19] S. Lee (London, 1827), Edward Backhouse Eastwick (Hartford, 1852; republished by Octagon Press, 1979),[20][21] Johnson (London, 1863), John T. Platts (London, 1867), Edward Henry Whinfield (London, 1880), Edward Rehatsek (Banaras, 1888, in some later editions incorrectly attributed to Sir Richard Burton),[22] Sir Edwin Arnold (London, 1899),[6] Launcelot Alfred Cranmer-Byng (London, 1905), Celwyn E. Hampton (New York, 1913), and Arthur John Arberry (London, 1945, the first two chapters). More recent English translations have been published by Omar Ali-Shah (1997) and by Wheeler M. Thackston (2008).

The Uzbek poet and writer Gafur Gulom translated The Gulistan into the Uzbek language.

United Nations quotation

This well-known verse, part of chapter 1, story 10 of the Gulistan, is woven into a carpet which is hung on a wall in the United Nations building in New York:[23]

- بنی آدم اعضای یک پیکرند

که در آفرينش ز یک گوهرند - چو عضوى به درد آورد روزگار

دگر عضوها را نماند قرار - تو کز محنت دیگران بی غمی

نشاید که نامت نهند آدمی

- بنی آدم اعضای یک پیکرند

- Human beings are members of a whole,

- In creation of one essence and soul.

- If one member is afflicted with pain,

- Other members uneasy will remain.

- If you have no sympathy for human pain,

- The name of human you cannot retain.

U.S. President Barack Obama quoted this in his videotaped Nowruz (New Year's) greeting to the Iranian people in March 2009: "There are those who insist that we be defined by our differences. But let us remember the words that were written by the poet Saadi, so many years ago: 'The children of Adam are limbs to each other, having been created of one essence.'"[24]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lewis, Franklin (15 December 2001). "GOLESTĀN-E SAʿDI". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

- ^ http://www.leeds.ac.uk/library/spcoll/virtualtour/gulistan.htm

- ^ [Durant, The Age of Faith, 326]

- ^ Katouzian, Homa (2006). Sa‘di, The Poet of Life, Love and Compassion (PDF). Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-85168-473-1.

- ^ a b https://archive.org/stream/gulistnorrosega00eastgoog/gulistnorrosega00eastgoog_djvu.txt

- ^ a b http://www.sacred-texts.com/isl/gulistan.txt

- ^ a b Thackston, Shaykh Mushrifuddin Sa'di of Shiraz ; new English translation by Wheeler M. (2008). The Gulistan, rose garden of Sa'di: Bilingual English and Persian edition with vocabulary. Bethesda, Md.: Ibex Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58814-058-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chapter titles given in the 1899 translation by Sir Edwin Arnold, http://www.sacred-texts.com/isl/gulistan.txt

- ^ https://archive.org/details/TheGulistanOrRoseGardenOfSadi-EdwardRehatsek

- ^ a b Edward B., Eastwick (1852). Sadi: The Rose Garden.

- ^ The king referred to is Harun al-Rashid.

- ^ https://archive.org/details/TheGulistanOrRoseGardenOfSadi-EdwardRehatsek

- ^ Ibex Publishers' description of Gulistan, http://ibexpub.com/index.php?main_page=pubs_product_book_info&products_id=105

- ^ Malcom, John (1828). Sketches of Persia. p. 86.

- ^ http://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Le_Songe_d%E2%80%99un_Habitant_du_Mogol

- ^ Price, William Raleigh (1911). The symbolism of Voltaire's novels, with special reference to Zadig. New York Columbia University Press. p. 79.

- ^ Iranian Studies in the Netherlands, J. T. P. de Bruijn, Iranian Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2/4, Iranian Studies in Europe and Japan (1987), 169.

- ^ http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015012849298

- ^ http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/sadi-gulistan2.html

- ^ Eastwick, translated by Edward B. (1996). The Gulistan of Sadi / The Rose garden of Shekh Muslihu'd-din Sadi of Shiraz ; with a preface, and a life of the author, from the Atish Kadah ; introduction by Idries Shah (Reprint. ed.). London: Octagon Press. ISBN 978-0-86304-069-6.

- ^ in wikisource

- ^ http://classics.mit.edu/Sadi/gulistan.html

- ^ Payvand News 24 August 2005

- ^ Cowell, Alan (2009-03-20). "Obama and Israeli Leader Make Taped Appeals to Iran". New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

Further reading

- Omar Ali-Shah. The Rose Garden (Gulistan) of Saadi (Paperback). Publisher: Tractus Books. ISBN 2-909347-06-0; ISBN 978-2-909347-06-6.

- Shaykh Mushrifuddin, The Gulistan of Sa'di tr.W.M.Thackston, Ibex, Bethesda, MD. 2008